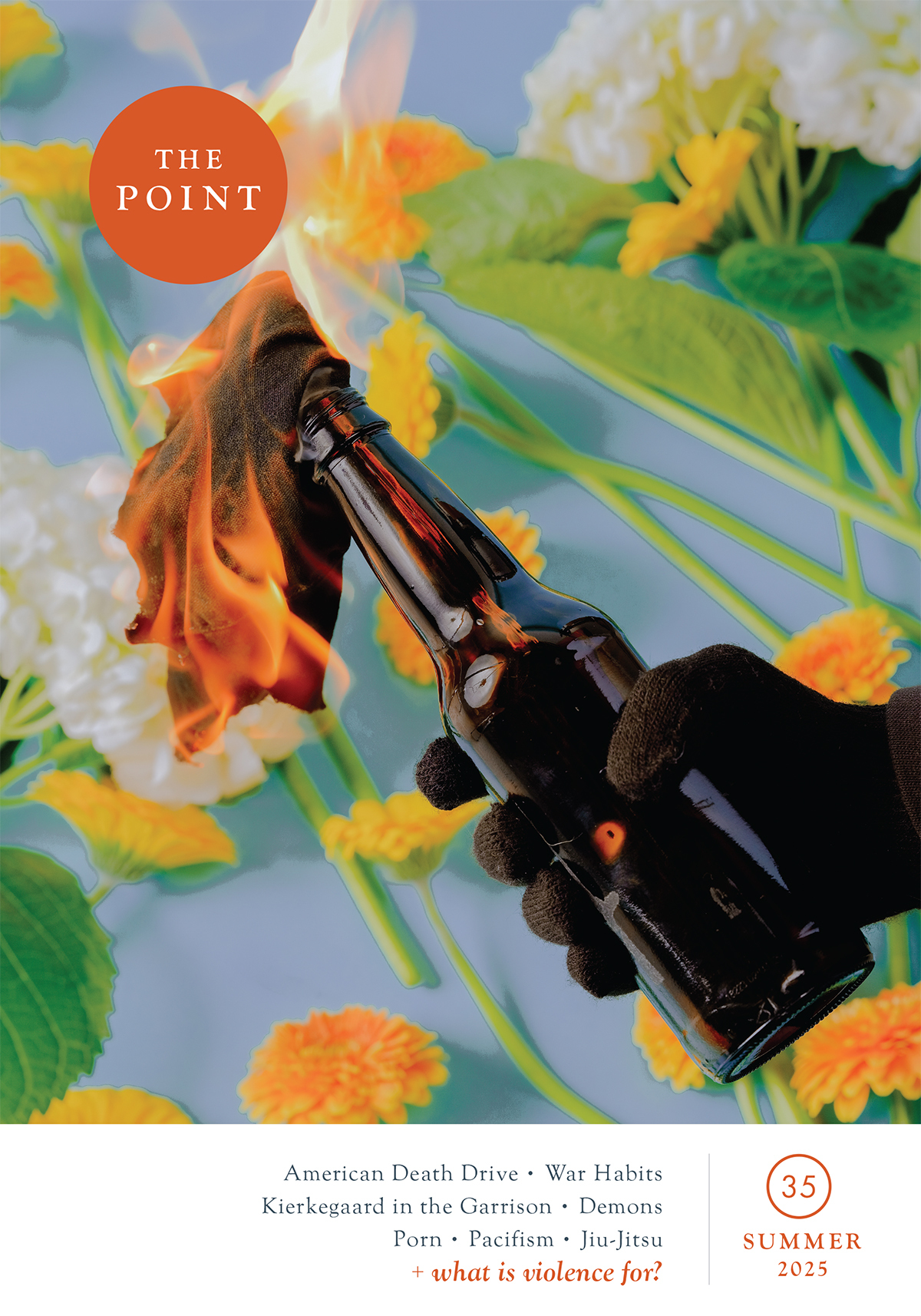

This issue on violence, the second The Point has ever devoted fully to a theme, was conceived in response to a number of questions or confusions.

On the 30th of March, 1981, John Hinckley brought us into the world we all live in today.

Christian pacifism irritates because it demands what the biblical scholar Richard Hays calls “the conversion of the imagination”—the overturning of certain assumptions that modernity lives by.

While “everyone” may understand the pragmatic or raw emotive reasons for violence, I’m not sure anyone understands sadistic violence sans motive, especially when acted out on helpless victims or in the context of social normalcy. Or maybe we do understand.

On any given day for the past quarter of a century, the United States was probably dropping bombs on a country somewhere.

Violence had not just wrought metaphorical transformations in Syrians, turning them at points into bystanders, accomplices, exiles, perpetrators, victims and (for now) a free people. It had also turned their bodies and even their unborn children into repositories of what had happened.

Tonight, across this country and on bases far afield, young American soldiers will take shifts guarding explosives.

On March 13, 1881, Emperor Alexander II left the Winter Palace to inspect a St. Petersburg military parade.

It was this convergence that made it so obvious, and so culturally confrontational, that Manson and My Lai shared gruesome content and form.

Girard did not deny Foucault’s insight that our modern institutions bear traces of their archaic predecessors. But this did not lead him to conclude that the effects of replacing blood sacrifice with a judicial system were merely superficial.

“To some extent—to a large extent—maintaining one’s innocence is self-delusion.”

Photography, wrote Susan Sontag, is “the gentlest of predations.” But is photography necessarily a violation? What is actually involved in the work of documenting violence? To answer these questions, we surveyed photojournalists and conflict photographers from around the world this past spring.

As soon as the owner of an old wardrobe/television/bicycle pushes it off the ramp, as soon as it’s “in there,” as they say at the Berlin Sanitation Department’s waste disposal sites, it no longer belongs to him; instead, it becomes the property of the department.

Basically, because I’m so interested in what’s popular, this essay has to be about what normal porn actually is, rather than about the goings-on of some esoteric and richly suggestive kink community about which we would love some novel and detailed news.

Declare what you think of any high-profile act of violence—Luigi Mangione’s alleged act of corporate assassination, the death of George Floyd while restrained by police or even “the slap” at the 2022 Oscars—and it’s easy enough for someone to suss out your opinion, political affiliation, class and what kind of man you think you are.

Is now really the right time to talk about the left’s political violence problem?

If 2025 were a movie, it would begin at sunrise on New Year’s Day, in the porte cochère of Trump International Hotel Las Vegas.