Whatever one thinks about the moral status of the existing global order, it is hard to imagine circumstances in which philosophical critique would make a difference to it. What came about through the workings of power politics will almost certainly end, if it ever does end, through the workings of power politics. The question for politically engaged intellectuals is what to make of that fact.

Despite the worry that sometimes flares in my body, I have felt that survival, too, needs a cure. That is the work of heaven and of the Promised Land, which lift the eyes of the lowly and sow ambition in the dead. Albert Cleage spent his life juggling the endless search for an earthly heaven with Lorde’s directive to always take care of ourselves together. He never stopped asking two questions: What is the point of black survival if not to aim for the highest good? Why aim high if you can barely survive?

If history has one clear lesson to offer, it is that building a new society on the assumption that humans are natural communards leads all too often to disaster. Time is running out. We must stop burdening our environmentalist critique of capitalism with utopian assumptions about human behavior.

Artists can offer us fantastic symmetries of tamed discord, but these remain silent, beautiful objects unless we put into practice their wisdom—the wisdom we gain these days from the practice of social distance. What will we take with us when we return to the world of people?

What is now not viable in Hegelian terms is a form of capitalism that works actively to suppress and distort what the requirements of labor, production and trade should have taught us: the depth of a mutual dependence that ought to be reflected in institutionalized forms of mutual respect and solidarity.

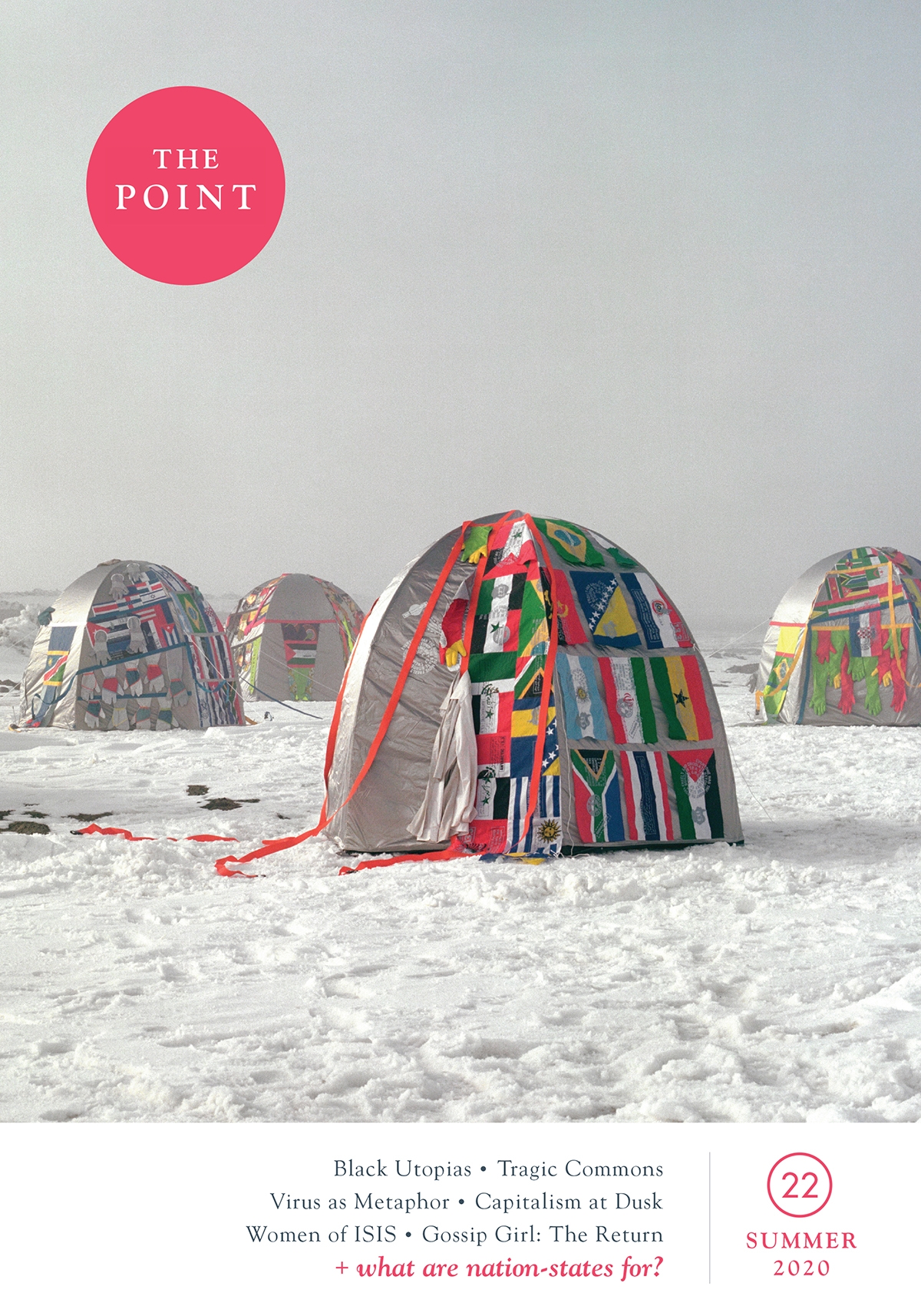

The coronavirus has only made the alignment between nationalism and a certain sector of the financial elite that much clearer. There are audible sighs of irritation that the nation-state—so long a faithful partner in subduing labor unrest and bailing out one strategic corporate bankruptcy after another—now has to be mobilized to keep consumers and some workers alive. In the face of the virus, national elites have not so much mobilized narratives of the nation as indulged a series of nationalist tantrums.

During the summer, I kept asking myself if I should just go home and be a journalist there, in service of the people. That is not to say in service of my “nation,” since Hong Kong is not recognized as a nation, and never has been.

Here’s the irony: a growing number of conservatives realize that it will require the assistance of the state to correct many of the problems that have been created by the state—problems caused by the progressive bias against the local, parochial and particular. A further irony is that a national conservatism, targeted toward the aim of “conserving” families, neighborhoods, communities, regions, if it is successful, will actually make our identification with the nation less important, and certainly will make our reliance and focus upon Washington, D.C. less all-encompassing.

But while a feeling of responsibility to humanity may be morally sound in itself, is it actually responsible? Not just Burke with his little platoon but a long line of liberal philosophers stretching back to David Hume have argued that, in practice, the great majority of human beings feel the strongest real commitment to those closest to them, and this sense weakens the further it is extended.

The passport, certainly, cannot settle the seemingly simple question: Where do I come from? Maybe it is Syria and Palestine; maybe neither. Sometimes I identify with what a German immigration officer accidentally stamped on my documents and future German passport, “ungeklärt”—undefined.

Patriotism is a moral mistake and an intellectual mistake, a mistake twice over. We are all subject to it.

Hong Kong is again in the news with Beijing seeking to pass anti-dissent national security laws; crucially, it plans to do so via the National People’s Congress, sidestepping Hong Kong’s own legislature. To Hong Kongers who care about civil liberties, this feels like the last straw. Then again, it’s been a year of many last straws.

Sontag’s ethic is one of truth: we are to see illness as it really is. But what is the truth about illness?

Moaveni questions the very idea of “radicalization,” putting the term in scare quotes and describing it skeptically as “some fuzzy ideological process” and “a notion that reliably elicited Western donor funding to local civil society organizations.” But what these women did strikes me as very radical indeed.

Sandersism’s diagnosis of the American condition is an explicit inversion of the traditional form of American exceptionalism. America is not a shining city on the hill, a beacon to the world. It is instead a trash heap whose subterranean flames glumly flicker and yet whose fumes somehow manage to pollute the globe. America is not merely fallen; it is the devil itself. (“God damn America!”) If America is exceptional, according to Sandersism, it is exceptionally bad.

The girl so perfect she must be violated is Serena van der Woodsen, a gold-plated human thoroughbred played by Blake Lively, who has recently returned to New York after spending some time hiding out at boarding school in Connecticut. Her best friend—and later Chuck’s lover and co-conspirator—is a brunette named Blair Waldorf who is played by Leighton Meester, and dresses like an American Girl doll whose ethnicity is “bitch.”