AMIRA

On Tuesday, after she’s walked for hours, she decides to sit at a coffee bar and order a cappuccino in her husband’s honor.

On one of their earliest dates, the third or fourth, he took her to the Appian Way Park, the Tor Marancia section. During the bus ride, and even more so once they arrived, he was visibly proud to be showing her—a native Italian—a piece of Rome she didn’t know. Afterward, they sat in a charming nearby coffee bar with outdoor seating. Even though it was already late afternoon, Ayoub ordered a cappuccino. When the waiter sniggered, she felt a mix of pity and embarrassment. But Ayoub wasn’t bothered. He couldn’t help it, he explained, he loved cappuccino too much to limit himself to having it only in the morning, the way “real Italians” did. “They can call me a dumb Arab if they want,” he said. “They can laugh. But I know I’m a dumb Arab with a delicious drink. Sorry if I embarrassed you, though.”

“No,” she said. “Not embarrassed.” Saying the words made them true. She called the waiter back and changed her order to a cappuccino. From then on, late-in-the-day cappuccinos were one of their rituals. At the coffee bar by the Appian Way Park, they became friendly with the owner, who cheered them on. “Maybe you Arabs could teach us something about being Italian,” he said. “If everyone was like you, I could sell cappuccino all day and make more money.” Arabs. Plural. They never corrected him, opting instead to smile softly at each other and enjoy the moment. Now each cappuccino she drinks alone is money she could be putting away toward rent. She knows that. But she needs to keep the ritual alive.

She’s walking home when her phone starts to vibrate in her purse. SARAH LAWYER OFFICE. It takes her more than one try to accept the call, her hands are shaking, she keeps missing the button.

They have a system. Sarah uses it with many of her clients. For most updates, she uses email. If she has information that is not urgent but, for whatever reason, cannot go in an email, she sends an email or text proposing three possible times for a call. She makes unscheduled calls only if she has truly urgent news, news she knows Amira needs to hear right away. The threshold for needs to hear right away has never been defined, and Sarah has crossed it only twice. The first time was to tell her that Ayoub seemed to no longer be in Pakistan—but that no one knew where he was, or why. The second time was two weeks later, to tell her that, apparently, he’d been held by the Pakistani secret police but was now almost definitely in Morocco. It was in this conversation that Amira first heard the words Temara Prison. Until then, she’d thought it most likely he was lying in a hospital where for some reason they couldn’t identify him, maybe his wallet had been thrown from his body in a car crash and he wasn’t yet conscious. Sarah’s system is supposed to save her clients stress by reducing the number of times they have to hold a ringing phone in their hands, suffocating under the weight of every terrible thing they might be about to learn, all the possibilities they cannot help having read about in the newspapers or online, plus all the permutations of those possibilities their minds can’t help generating. The system is also supposed to make it less stressful to check (or not check) email: one can always know that if it’s something truly urgent, Sarah will already have called.

She leans against a lamppost. Whatever she is about to learn, dozens of people walking down the street will witness her learning it.

“Hello, Khadija?” It’s Sarah, but for some reason she’s speaking English.

“Excuse me?”

“Khadija, can you hear me? It’s Sarah.”

“No, this is Amira.”

“Amira? Oh God, I’m—”

“What is it? What happened?”

“No, nothing, Amira.” She switches to her broken Italian. “It is a nothing. I’m sorry. I call the wrong number. I mean to be calling someone else. I am sorry, so sorry, very extra sorry. There is no information that is new. I am so sorry. I am… tired. I make a mistake. I am sorry.”

“Oh.” The sickening chemical collision of relief and panic in the gut.

“I am tired and I call the bad number. The not-right number.”

“That’s okay. It’s okay, Sarah. Khadija is… another client? The wife of another client, I mean?”

Sarah sighs. “Yes, the wife of a client.”

On the way home she cannot stop herself from going into the Somali internet cafe and googling: Khadija rendition wife, Khadija rendition Sarah Mayfield, Khadija CIA rendition, Khadija Guantanamo, Khadija husband Guantanamo, Khadija husband Temara. She finds nothing—nothing she hasn’t seen before, nothing specific to Khadija, whoever she is. She should stop but she doesn’t: Ayoub Alami, Ayoub Alami Temara, Arsalan Pakistan prison, Arsalan CIA detained. And so on. Until she can’t bear it.

She has an email from Mourad, Ayoub’s best friend from childhood, asking the same questions he always asks in his emails: if there is any news, if there is anything he can do, if she needs money (though he never puts it so directly), if she wants to come and stay with his family in Madrid, for any amount of time. I know Ayoub would do anything for me, and I will do anything for him.

●

When she gets home that evening, there is, for the first time in months, a padded Red Cross envelope in her mailbox. The Amira of two years ago—maybe even the Amira of six months ago—would have run upstairs right away, ripping open the envelope as she ran. But tonight she moves at a normal pace. Even when she’s inside the apartment, she takes her time, letting the envelope sit on the kitchen table while she pees, washes her face, pours a cup of water. She has accepted that the letters are guaranteed to say nothing new of substance. I miss you, I am thinking of you every day, I am looking forward to seeing you again. Sometimes I ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇ ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇ . I wonder if ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇ ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇ ▇▇▇▇ .

And yet, staring at this new letter from across the kitchen, she feels the desire to rip it open building within her, pushing against her from the inside like helium against the interior skin of a balloon. She picks up the phone to call Meryem. After the last time she got a letter, she talked to Meryem about it, trying to describe the experience of opening them, how sad and tired and alone they made her feel. Meryem took her hand and told her to call the next time she got one. “I’ll come over as soon as I can,” she said. “Then you won’t be alone.”

She starts dialing but pauses halfway through. She cannot help wondering: To what extent did Meryem’s offer come from a desire to make her life more bearable? And to what extent was it about curiosity? To what extent was Meryem looking, consciously or not, for an opportunity to dip into someone else’s raw sadness, protected by the knowledge that she would soon be safely back at home with her husband and children?

She hates thinking this way. She puts the phone down and opens the letter: first the outer Red Cross envelope, then the flimsier inner one, on which Ayoub has written her address. She knows before she has the letter out that it will smell of Temara—mold, piss, shit, darkness—and knows that no matter how many times she resniffs the letter, she will be unable to tell if the smell is really on the paper or if it has been placed there by her imagination.

Dear Amira,

I am thinking of you even more than usual today, because ▇▇▇ ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇. Sometimes when things like this happen, it feels like I will be here forever. Sometimes I cannot remember how long I have been here. It seems like I just arrived only yesterday. A man down the hallway from me ▇▇▇▇▇▇ ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇.

God willing, this will be over soon. I am sorry for the pain that I know my situation must be bringing you. Someday I hope it will be a distant memory.

▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇ ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇ ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇,

Your husband,

Ayoub

The letter is, like all of his letters, written in Italian. She has no way of knowing if he does this for her benefit, or in hopes of stymieing the censor. There is no indication of when it was written. It tells her nothing. It does worse than tell her nothing: it takes Ayoub—her Ayoub, the real individual—and overwrites him with an infinity of possible Ayoubs, each Ayoub changed forever by whatever he has had to endure, whatever he is still enduring (potentially right at this very moment), whatever he might yet have to endure in the future. Reading the letters makes Ayoub feel farther away. Not to read the letters would feel wrong—would, in the end, also make Ayoub feel farther away. Writing responses of any substance feels dangerous: Who knows who would read what she said, and what use they could put it to? Writing letters of no substance feels painful. Every day, no matter what she writes or doesn’t write, no matter what she does to keep their life intact, Ayoub is farther away.

She puts the letter back in its envelopes and takes it to the spare room—the room where her guests would stay if she ever had guests, and where their child would sleep if they had a child. Sometimes she misses this nonexistent child. A child would tell her what to do next: Take care of me. Each thing she did for the child would also be, unambiguously, something she was doing for Ayoub. But just as often she is sick with relief that no person is growing up dependent on her, absorbing through the air of the apartment her daily struggle to keep herself from screaming because she knows that once she starts screaming she won’t stop.

She puts the letter in the shoebox with the others, lowers herself to the floor, lies flat on her back, looks at the ceiling, and does a breathing exercise: empties her lungs by blowing out through her mouth, inhales through her nose for four seconds, holds her breath for seven seconds, empties her lungs by blowing out through her mouth…

If she had a child, this is the ceiling the child would look at every night. This is the window the child would see light coming through. The child would have no memory of Ayoub. She would show the child pictures and say, first in Italian and then in what is left of her Arabic: father.

MEL

They met in the library. After a few whispered conversations about the papers they were writing, Art asked her out. Their first date was supposed to be The Killing Fields and dinner. But on the afternoon of the agreed-upon day, he called to say that the university endowment board had just voted to continue investing its funds in South African companies. There was a sit-in happening at the chancellor’s office, and probably a march afterward. Could they do the movie next time?

She followed his directions to the imitation South African shantytown the protesters had built outside the chancellor’s office, and arrived just in time to join the march. It was obvious that Art knew people there. Until then, her own knowledge of protests was almost entirely secondhand: newspapers, magazines, TV, movies. Especially movies, which was probably why walking down Franklin Street with Art felt movie-like, every second part of an unfolding, accumulating story that their presence was revealing, to themselves and everyone watching, their bodies combining with all the other bodies to stop anything else from occupying the street other than their demand, which was suddenly Mel’s demand, too: divest! It was magic, and the magic was still there in the morning when she woke up in Art’s bed. He started taking her to speeches, panels, documentary screenings, more marches, sit-ins, letter-writing sessions, strategy debates. Apartheid. CIA meddling in South America. Nuclear proliferation. She was 21. He was 25, a grad student. They never saw The Killing Fields.

They moved together to a small wooden house on Carlson Street. The day after they moved in, Mel was unpacking when the doorbell rang. And that was how she met Linda, who was standing on her front stoop, smiling as if she already knew they would become best friends, holding a pie tin covered in aluminum foil and a brochure: “The Top Dangerous Myths of the Nuclear Lobby.”

Linda and her husband, Robert, lived just four doors down, in a small wooden house that was almost identical to theirs. That night, the four of them sat on Linda and Robert’s screened-in porch—which was the same as their screened-in porch, but with a table and chairs—eating fish tacos and drinking and talking past midnight about politics, activism, school, childhood, what they were reading, what they were learning. At least once a week for the next two years, they did it again: stayed up late sliding effortlessly from the immediate (whether so-and-so had procured the correct permit for an upcoming march) to the grand (the future they were hoping to use the march to call into being) and back again (immediate) and again (grand). Did marches work? What would this particular march actually accomplish? Should they order pizza? Who had to be up early tomorrow? Who was ready for another beer? Dinner was never just dinner, going for a walk wasn’t just going for a walk. Everything was bigger. Everything connected.

Later, when she looked back on this time of her life, what Mel remembered most was a certain easy intimacy. They stopped by each other’s houses just to see who was home. They went grocery shopping together, cooked together, ate together, marched together, locked arms on Franklin Street. They invited people over to show off what they had, the friendship they’d found. Hugging Linda and Robert goodbye at the end of an evening they’d spent together, she often felt sure not only that she and Art were going to make love once they were alone but also that Linda and Robert were, too, and that all four of them knew it but didn’t need to say anything. She and Art got married in Linda and Robert’s backyard, with Robert officiating, giving a beautiful speech about loving in history. She’d never been so happy, and never known for sure that happiness like this was actually possible for grown-ups.

Art was finishing a graduate degree in social work, tutoring undergrad psychology majors for money. Mel was halfway through a history major and working at a health food store. Robert had just started a doctorate in history. Linda was finishing a political science major and working at a garden supply center, always bringing home seeds and clippings and plants for use in their little yards. Mel sometimes suspected that either Linda or Robert had some other source of money at their disposal—but she never knew for sure.

She understood that they would leave Carlson Street someday, but she couldn’t imagine why, or when. Then Art finished his degree and struggled to find a job that put it to use. He tutored more, but found tutoring increasingly unbearable now that he was officially qualified for something else. In private, he complained to her that everyone but him was still on some kind of track. His interest in activism swung back and forth. Sometimes he seemed done with it, as if, without knowing where his own life was headed, he couldn’t marshal the energy to be interested in where the rest of the world was going. At other times, he seemed like more of an activist than any of them, as if channeling the energy he wasn’t able to pour into his career. His demeanor at protests changed, and he began—in Mel’s eyes, anyway—to resemble just slightly the people, mostly men, who showed up primarily so they could engineer antagonistic confrontations with the police. She worried, but not terribly. Everything would be normal again, she felt, as soon as he found work.

How would their life have been different if the state health department had not decided to open a new public health clinic in Springwater, serving all of Yew County?

If, when looking for the clinic’s first employees, the state hadn’t written to Professor William Townsend of the University of North Carolina School of Social Work, urging him to solicit applications from his most promising recent graduates?

If Art had never taken any of Townsend’s classes?

If he’d been offered any other job in his field?

If, in December 1985, a few weeks before her graduation, Mel had not found out she was pregnant?

At first they thought Art might commute. But the drive was an hour each way, which meant two hours away from the baby. Plus gas money. Plus paying Durham rent on a Springwater salary.

Linda took the news hard. It was as if, to her, their decision to leave Durham amounted to a judgment that nothing had ever been good there. Every time they got together, she retold the story of the one time she and Robert went to Yew County, for a counterprotest against a KKK rally in Springwater. On the drive they passed a sign by the side of the highway: WELCOME TO KLAN COUNTRY. It was rusted and full of holes—but it was there. “We couldn’t believe it, could we?” she said. “Klan Country! In 1984!” The rally itself, at least in Linda’s telling, was even more shocking. She and Robert had been prepared, she said, for the white hoods. What they hadn’t known to expect was all the people who showed up wearing normal weekend clothes, no hoods or masks at all. “On the Klan side! These are your new neighbors.”

They promised they wouldn’t be gone long. They would keep looking for jobs “back here.” Something would come up. In the meantime, an hour wasn’t far. They could visit on weekends.

“That’s what everyone says,” said Linda. “That’s what everyone says when they move away.”

The first time Robert and Linda came to visit Springwater, they’d barely walked in the door when Linda said, “I can’t believe it—that Klan sign is still there!”

Which, yes, it was. They were aware. Of course they were aware.

But why did it have to be the very first thing out of Linda’s mouth?

When she went to the bathroom, Robert quietly apologized. “She’s just hurting. She misses you. We both do.”

The house they’d rented in Springwater was spacious but uncomfortable: dusty in a way that no amount of dusting would ever address. Without Durham’s steady stream of students and visiting professors, the rental market had less to offer; it made more sense to buy, especially with a child. So they bought, telling themselves that buying didn’t mean they had to stay. But their inspector failed to detect the sinkhole in the yard, let alone the fact that it was growing, threatening to swallow the house. There was a solution, which like many solutions could be summarized by a single word: money. Art got more clinical training. Got promoted. Got a raise. Once Michael started school, Mel started working again, first at Genova’s, making sandwiches and ringing up orders, because that was all she could find. She got a real-estate license, toughed it through the early years of getting her name out, learning the market. After that, moving would have meant starting over. They fixed the sinkhole. They started paying off the house faster. The house gained value. Michael grew up and made friends and didn’t miss Carlson Street, for the simple reason that he’d never lived there. Back in Durham, Robert became a professor. Linda went into business as a “nonprofit consultant.” Neither Mel nor Art was able to figure out if she actually made any money.

For a while, whenever they saw each other, Linda would at some point compulsively run through the news of every group and cause they were involved with or thinking about becoming involved with. Sometimes these updates felt like an accusation: Here’s something good you’re not doing, and here’s another, and here’s another, you’ve changed, you said you’d come back and you didn’t, and you won’t, because you’ve changed, and not for the better. Over time, the updates came less frequently. Then they stopped. When they saw each other, they didn’t talk about activism anymore, and didn’t talk about not talking about activism, either. Instead: Michael, their jobs, home improvement projects, vacations, the various approaches to exercise and food and sleep they were trying on their aging bodies. They were, it turned out, still capable of closeness. Maybe not the daily same-street intimacy of before, but something Mel felt sure could be just as deep. Linda and Robert loved Michael, and showered him with presents. He saw them as an aunt and uncle. In a fireproof safe in the back of their bedroom closet, and also in their lawyer’s office in downtown Springwater, there was a document establishing that if she and Art both died and Michael still required a legal guardian, he would go and live with them.

When, after many attempts, Robert and Linda decided to stop actively trying to get pregnant, and not to adopt, Mel and Art were the first people they told. They sat together in Linda and Robert’s living room—not on Carlson Street, they’d moved long ago—and all cried together, even Art, who never cried, and while of course Mel was unhappy that her friends were in pain, she was grateful to know they could all still sit and feel intensely together.

In the spring of 2001, Mel sold a house to a woman named Sheila Pacon, a longtime member of the local school board. A few weeks later, Sheila called to ask Mel if she would consider running for a board seat that fall. Officially, the board was nonpartisan: you ran as yourself, not as a Democrat or a Republican. But increasingly, Sheila said, everyone knew who was who, and board disputes broke down along party lines; she was recruiting Democrats with the energy to stand up to the Republican bloc and make it official that not everyone in Springwater worshipped George W. Bush. Mel didn’t run to impress Linda and Robert, but she did hope they would be impressed—that they might see her campaign as a direct extension of all their old conversations about how to nudge the world in the right direction. (They had, over time, shown a willingness to see Art’s work in this light.) She even hoped they might join her campaign, helping to design flyers and corral volunteers and knock on doors. But when she brought it up, she sensed that Linda was uninterested and that her lack of interest was motivated by a need, perhaps unconscious, to punish her. You abandoned us, now we abandon you, though of course, Linda never said that, or anything like it. When she won, her old boss at Genova’s, a man named Sam who normally did nothing without weeks of planning, was so proud that he threw her an impromptu victory party. Sandwiches on the house. She invited Linda and Robert. They didn’t come.

Serving on the school board was rewarding. She talked more to her fellow parents, worked to understand their perspectives, spent time learning how they thought. Selling houses had made her better at talking, and much better at listening. Too many of the other board members saw their job as to cut as much as possible: cut classes, cut activity budgets, cut teacher protections. She hated it. But she knew they were cutting less, and more carefully, thanks to resistance from her and Sheila and whoever else they were able to recruit case by case. From either party. It wasn’t glamorous. She had very few obvious victories to point to. But she never doubted that the work mattered.

She was just over a year into her first term when Linda called to invite her and Art to a protest in Durham against the imminent invasion of Iraq. The call was strange. Linda gave no preamble—no introductory acknowledgment that she was about to launch into a conversation of a type they’d stopped having long ago. It was as if, in her mind, they had already spent the morning discussing not just Iraq but this particular protest, when in fact they had never discussed either. “I think we can do it, Melly. I really think we can. We just need to push. We need to push and push and push.” She sounded like she was about to cry.

Neither Mel nor Art ended up attending the protest—or any Iraq protest. At least once a week, Mel got a new “IRAQ ACTION BLAST” email stuffed with details about meetings and protests Linda hoped people would attend, congressional offices Linda hoped people would call, links to articles Linda hoped people would read and forward to their friends and family. Articles about the complete lack of a Saddam-9/11 connection. Reports on how the CIA had been pressured to fake the necessary facts. Investigations chronicling the Bush family’s long-running and transparently pathological fixation on Saddam. Spiderweb diagrams that promised to illuminate exactly how Dick Cheney, his family and their nefarious associates stood to profit from invasion. Mel sometimes skimmed these emails and sometimes deleted them without reading and sometimes let them languish unread in her inbox. Art did the same. They never went to a single meeting, made a single phone call, gave any money. It wasn’t that they supported the war. Of course not. They were just… doing other things. Mel knew this explanation sounded pathetic, even when uttered only silently, to herself. At the same time, she felt strongly that this was the exact definition of adult life: selecting, from a near infinity of choices, to do some things and not others, knowing at every turn that you could be choosing differently, and that it was impossible to know for sure you were making the right choice. She did wonder, later, about the extent to which her cool response to Linda’s invitation was influenced by her old friend’s non-reaction to her school-board run. But she didn’t think it was possible to know.

The rest of 2003, they hardly saw each other at all. Again, it wasn’t something they ever talked about or made official. It was just a cooling, one that, most days, Mel hardly noticed or thought about. Michael started his junior year of high school and began researching colleges. Art got another promotion, becoming less of a full-time therapist and more of an administrator. She wasn’t sure it was a good idea: she couldn’t see him enjoying himself with drastically less one-on-one patient contact. He went to work earlier in the morning; he made more money.

In the fall of 2004, two more Democrats got elected to the board, and three Republicans retired, two of them replaced by fellow Republicans with even more interest in cuts and even less interest in compromise. Negotiations over the following year’s budget became so heated that it was decided that two board members—one Republican and one Democrat—should meet on their own, without the others, to hash out the general contours of an agreement. Nothing binding, but something they could all look at together and debate, rather than just yelling at each other. The Democrats picked Mel—they would have picked Sheila, out of deference to her seniority, but Sheila herself admitted that she wasn’t sure she could keep her cool—and the Republicans picked Bradley Welk, a local lawyer new to the board. Mel knew about him only what everyone in Springwater knew: that he had an office downtown, just off the courthouse square; that he could often be seen walking between his office and the courthouse; that he wore khakis and blue button-down shirts; that he played golf; that he had a son, Paul, who was Michael’s age; that he wore aviator sunglasses with silver frames; that his truck was always shiny and spotless; that his father, a prominent local Republican, had died over the summer. “Good luck,” said Sheila. “That’s all I can say—good luck.”

She had never cheated on Art and had never considered cheating on Art. Not with any degree of seriousness. Because it had crossed her mind so rarely, she’d never given much thought to why people had sex with people other than their spouses. Perhaps this is why, when she first slept with Bradley, she felt so unequipped to understand what was happening. In his office, of all places. They’d been discussing the possible responses of their fellow board members to their proposed budget compromise, and they were trading imitations back and forth—Bradley was pretending to be Norman Lightfield, who always used both hands for handshakes, no matter who he was talking to—and laughing and laughing, and then they were on his desk. Afterward, she didn’t think it would happen again. She told herself that the thrill had something to do with verifying that life was never fixed, that surprise was always possible—and that this type of thing didn’t have to be verified often to know it was true. Everyone was happy, or happy enough, with the budget draft they came up with; board meetings got less heated. A month passed, and this month seemed like proof that what happened on Bradley’s desk had really been a one-time thing. Then it happened again. Not on the desk, but. She felt sure she loved Art no less. She couldn’t believe how smooth Bradley’s skin was, and couldn’t believe the way its smoothness unlatched some trapdoor she’d never noticed right beneath her, how she fell through, faster every second. She’d never really thought about the smoothness of a man’s skin before. The only person she felt possibly able to talk to about it with was Linda, but she never did.

Every time, she thought she and Bradley were done; every time, they weren’t. She tried to avoid thinking about what it meant, because whenever she did, she ended up feeling horrible.

She read online about breakfasts: about how, if a school district made free or reduced-cost breakfasts available to its students, the federal government would pick up half the cost. She read studies about the impact of going without breakfast on children’s ability to learn. She looked up statistics about food insecurity and chronic hunger in North Carolina and, to the extent they were available, in Yew County specifically. She read about failure rates, repeat rates, dropout rates, the cost of summer school, the costs of an undereducated population. She spent an afternoon at a cabin on Angleton Lake with Bradley, drifting between sex, her argument on behalf of a countywide breakfast program, his devil’s advocate counterargument and, eventually, joint strategizing about how to sell it to the rest of the board, especially Bradley’s fellow Republicans.

The cabin belonged to a friend of Bradley’s; he didn’t say who, and she didn’t press for more. Before they left, they ran the sheets through the wash and hung them on a line outside. Over the summer they worked on the breakfast plan. Between the two of them they met with every board member individually, pitching the breakfast program in language designed to make that particular board member like the idea. They identified cuts that would make Republicans happy and that Democrats could convince themselves to live with. They lined up support from Pastor Fred, from the chamber of commerce, from the Herald. All this time, they didn’t sleep together. Maybe, she thought, it was over.

In August she and Art drove their car behind Michael’s car to Asheville, got him settled in his dorm room, and hugged him goodbye. Afterward, they wandered the campus together in silence, wondering how time had passed so quickly. Back at home she missed his foods in the fridge, his shoes cluttering the foyer, the layered clouds of teenage stink that wafted from his room after stretches of particularly intense neglect. He called every few days, sounding flat and lost, and they knew he was struggling. For them, college had been a joyous liberation from unhappy families to which they never returned, but Michael’s childhood had been happy—hadn’t it? Maybe, for him, liberation wasn’t as tantalizing. She’d always been proud of her relationship with her son—always felt that she knew him better than the average mother of a teenage boy. But now she wondered if that might have been an illusion. He’d been gone for only a month, but it felt like much longer. A whole era. Every day she wanted him back, and every day she wanted him to be okay where he was, and every day she wondered if this was how she would feel forever.

●

In the days that followed Mel would spend a great deal of mental energy on pointless questions. How did they not hear a car pull up? How did they not hear the front door open? How did they not hear that someone was moving around downstairs? Exactly when did Michael come in, and exactly what did he hear? What was he thinking, standing there by the sink? How long would he have stood there waiting if no one had come downstairs?

As soon as she heard him drive off, she called. They could talk. It could be contained. How? Somehow. No answer. Bradley left but came right back, red-faced and shouting about his truck. He didn’t even knock. She almost had to push him out the door, insisting they would talk later, that he had to leave. Now. She tried calling again. No answer. She threw herself into erasing every physical trace, real or imagined, of Bradley’s presence in the house. Stripped the bed. Put the sheets and pillowcases in the wash. Did the dishes. Vacuumed the carpet at the top of the stairs, then the carpet in the bedroom, and then the rest of the house, always making sure the home phone and her cell phone were both nearby. She took a shower, scrubbing off every particle of Bradley and what they’d done together, sliding open the shower door every half minute or so to check the two phones, which she’d put on a towel on the floor, both set to ring at the highest possible volume. After the shower she changed into pajamas, moved the sheets and pillowcases to the dryer, put her towel and Art’s towel and her purple robe in the wash. She went into Michael’s room, as if she might find something there that could calm her down, and she was sitting on his bed when she called him the third time, and again got no answer, and again hung up before the end of his voicemail message. On Sunday night Art came back from his conference, unpacked his suitcase, and went to sleep early. Just before he fell asleep, he thanked her for cleaning the house.

●

On Tuesday she leaves work early, stops by Genova’s, orders an egg salad sandwich to go, makes some small talk with Sam, and drives home, where right away she takes out a yellow legal pad and three pens: one black, one blue, one red. She makes a cup of tea, sits at the kitchen table, and forces her eyes shut, attempting to quiet everything but the task in front of her. Quiet the unfolded laundry. Quiet the imminent need to replace the water heater, to read the Consumer Reports article about how to pick a water heater. Quiet the fact that she has called Michael six times in four days. The fact that he hasn’t answered. The look she keeps convincing herself she sees on Art’s face. Quiet everything but one question: how to most effectively use her time at tomorrow night’s public school board meeting to sell the new budget to the citizens of Yew County—or, in truth, to the small percentage of them who bother following school board business.

This is not just selfishness, she tells herself. She is not just looking for a break from the torture of reviewing her own mistakes. The work she wants to do—the work she will start doing if she can make her mind quiet enough—is important. Objectively important. A better school budget will make Yew County a better place. Make people’s lives unambiguously better. Children’s lives. Parents’ lives. Surely this justifies turning away from the mess of her life for a few hours.

On the blank top page of the legal pad, she writes, with the blue pen: This is not meant to be the final word on next year’s budget. It’s meant to be a starting point. That’s why we’re releasing it almost six months before it’s due. Now we need your feedback.

She underlines your with the red pen. Your feedback. She tears off the piece of paper. She crumples it. On the next piece, she writes a list of everything the draft budget accomplishes, then tears that piece off, too, but doesn’t crumple it. On the next piece of paper, using the blue pen, she writes words that she thinks might help frame those accomplishments in a way that appeals to an archetypal Yew County Republican with an interest in school board business. She tears this piece off, too, and on the next piece does the same exercise, but for Democrats. Then she tears that list off and sets the three lists—accomplishments, Republican framing words, Democratic framing words—side by side and lets her eyes roam between them. She nibbles on her egg salad sandwich, idly wondering how many Genova’s egg salad sandwiches she’s eaten over the years.

She tries to let the right words come.

Tries to push away the memory of Michael standing just a few feet from where she’s sitting. The disgust on his face.

Is this made more difficult by the fact that the budget is just as much Bradley’s project as hers? That it’s their project?

Of course.

But there’s nothing to do about that now. She’s a fool, and she’s made a mess—but these aren’t reasons to abandon a good budget.

It isn’t the perfect budget. It isn’t everything that she would ask for, were she able to snap her fingers and get whatever she wanted. But it is better—much better, she is absolutely sure—than anything else that could possibly pass, and much better than anything that would be on the table had she and Bradley not put it there.

She clicks to retract the tip of the blue pen. Clicks to extend it again. On the new top sheet of the legal pad, she writes: This budget commits us to making sure all of Springwater’s children start the day on a full stomach. Crosses it out. This plan makes us a district where no child starts the day distracted by hunger. Crosses it out. When all children in our district have breakfasts, they all have the chance to succeed. Crosses it out. It feels good to work: to let everything slip away, to move toward the moment when all that remains is exactly what she wants to say, exactly how she wants to say it.

When every child in our district has breakfast, we all get better value and less waste from our tax dollars.

When all the children in our district get to eat—

Her cell phone buzzes on the table and she peers over to read the caller ID: LINDA/ROBERT HOME. She decides to let it go to voicemail.

When every child in our district starts the day with breakfast, it actually benefits—

Now the landline rings. She considers ignoring it in the name of maintaining her concentration. The only reason she gets up is because of the chance, however small, that it’s Michael, finally calling her back.

LINDA/ROBERT HOME.

Inertia takes over. “Hello?”

It’s Robert; right away he asks if Art is home. And then Linda is on the line too—on another handset, it sounds like—also asking if Art is home. “Have you heard of a company called Atlantic Aviation?” says Linda. “It’s not really a company. It’s a shell company, and it’s—but, well, have you heard of it?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Are you sure?”

“Pretty sure.”

“Well. It’s in Springwater.”

“Okay.”

“Your Springwater.”

“Okay.”

“It’s the CIA,” says Linda. “It’s the CIA flying these flights. Torture flights. There’s going to be a story in the Times. Can you believe it? Springwater in the New York Times? Can we come for dinner tomorrow? Or Thursday? There’s a lot to talk about.”

●

After they’ve hung up, she sits back at the kitchen table and stares at the torn-out legal pad sheets—accomplishments, Republican framing words, Democratic framing words—hoping to pick up where she left off. But she’s shut out now. She stands up and walks back to the living room. She’s still holding the phone. She walks to the little alcove in the back of the house that they have always called “the office,” giving it three or four more notches of dignity than it deserves. She sits at the computer and googles. CIA Atlantic Aviation, Springwater torture, CIA Springwater shell company, Springwater torture flights, variation after variation—nothing. She googles Yew County Airport and it looks like she remembers it: a single-story brick building, a few aluminum hangars, and just one runway. She googles torture flights and the photographs come up. The naked men, the pyramid, the hood. She’s seen them before, whenever they were in the news. She doesn’t look closely and doesn’t click to make them bigger. She closes the web browser.

●

Tuesdays are the only day of the week when Art still does one-on-one counseling, which means that on a usual Tuesday night they don’t say much to each other; after six hours of talk therapy, he’s done talking. It takes time for the day’s conversations to loosen their hold on him, for anything new to be allowed in. She says nothing about Linda and Robert’s call when he first gets home, nothing about it when he opens his beer, nothing about it for their first several minutes at the dinner table together. She waits as long as she can. “Robert and Linda called today,” she says.

He looks up from his plate. “Oh?”

She tries her best to relay what they said. She doesn’t know if torture is a word she’s ever said, out loud, to him or anyone else. She remembers hearing, back in Durham, about torture—but as far as she can remember, that torture was in South America.

“How do they even know about this?” says Art.

“They didn’t say.”

“How do they know what’s going to be in the Times?”

“I don’t know.”

“Atlantic.” Art says it again, slower—At-lan-tic—like a new word from a foreign language. “Never heard of it.”

“Me neither.”

“And what do you think they mean, a lot to talk about?”

“I don’t know.”

He takes a sip of beer and says something soft that she hears as “Heard from Michael today.”

Everything inside her freezes. “What?”

“I said, did you hear from Michael today?”

“Oh. No. Why?”

“Just wondering. It seems like he’s already calling less and less.”

“Well, I don’t know,” she says. “Maybe he’s making friends.”

“Or falling in love.”

“Maybe. Maybe he’s being seduced by a charming grad student.”

“Is that what happened?”

“As I recall, yes.”

“Well, if so—lucky her.”

“So, can they come for dinner on Thursday?”

“Sure, sure.”

Once the dishwasher is running, she packs herself tomorrow’s lunch, which is really just snacks she’ll be able to eat in her car if she has to. Carrots, hummus, nuts, a hard-boiled egg. She can hear that Art is in the office, and has the urge to go ask what he’s doing. But she leaves him alone. It’s Tuesday.

Later, though, when he’s upstairs getting ready for bed, she goes to the office and turns the computer back on and checks the browser history. She’s never checked the browser history before, and only knows it’s an option thanks to an article she read over the summer in her dentist’s waiting room: “How to Find Out If Your Teen Is Using Online Pornography.” Michael was still home then, but she had no temptation to snoop on his browser history. She remembers feeling superior to other mothers—superior to their panics about what their sons were up to, the kind of men the world was turning them into.

She clicks to open the web browser. Because she can’t explain what she’s doing, she doesn’t exactly believe that she’s doing it. She’s watching herself in a movie, waiting to see what the character named Mel decides. She pulls up the browser history. Atlantic Aviation, CIA Springwater, torture flights.

Upstairs she finds Art already asleep, a sci-fi paperback splayed open on his chest, rising and falling with his breath. She’s grateful. She doesn’t have to figure out what to say or not say, doesn’t have to wonder what he is sensing or not sensing in her facial expression, in her posture, in the air between them. Because he’s asleep, it’s possible to feel that nothing is going unsaid. She’s just standing in her bedroom, watching her husband rest.

●

The next evening she arrives at the high school ten minutes early.

All day she has resisted calling Michael again—and now, sitting in her car, she gives in. “Michael, it’s your mom. Call me back, please. Even if you’re busy, just call back to let me know you’re all right.”

Being at the high school feels different, knowing he’s hundreds of miles away.

Inside she goes to the auditorium and heads straight to the stage, where, as always, three long folding tables have been set end to end so all nine board members can face the audience. She takes her usual spot: third from the right on what is, by unspoken rule, the Democrats’ side. She sees Sheila’s purse in Sheila’s usual chair, fourth from the right. She spots Bradley in the audience, talking with a couple she doesn’t recognize, laughing warmly at something the husband just said.

She spots Pastor Fred, sitting by himself at the far end of a row of chairs toward the front of the auditorium. Their eyes meet, and he gives her a quick little nod.

The meeting starts. She’s grateful that Bradley’s seat is four down from hers, and even more grateful that it is perfectly within the bounds of normal behavior for the two of them to more or less ignore each other.

Mel gives her introduction and decides on the spot to use the line about how subsidized breakfasts unlock value from tax dollars. All the other board members say a few words, everyone commending everyone else for their willingness to compromise. Some draw attention to a favorite feature or two of the draft, but everyone avoids hammering too hard on anything specific. Thanks to Bradley’s nudges, all the Republicans think that they’re the side getting more of what they want. Thanks to Mel’s nudges, all the Democrats think the opposite. Each side is aware of what the other thinks, but each side thinks the other is wrong. Both sides are happy.

There’s something dreamlike about the fact that it’s actually happening. That they’re actually one step closer to putting breakfast in the stomachs of students who would otherwise go without breakfast.

What looks to Mel like thirty members of the public have shown up, and somehow none of them voice any serious objections. Of course, objections could come later. But it’s undeniable: things are going well. Pastor Fred keeps shooting her a look—and he’s probably shooting the same look to Bradley—that means he’s not sure what to do. He’d agreed to come and offer remarks to calm people’s objections, using the authority of his position to make feeding children sound simultaneously like the Christian thing to do, the conservative thing to do, and the liberal thing to do. But now no objections are materializing. He gets up and says a few words anyway, which is a good thing, because a Herald reporter has shown up, and a quote from Pastor Fred stands a good chance of making the story.

In slightly different circumstances, she and Bradley would surely find a way to share a quick second of celebratory eye contact. But tonight she looks either out toward the back of the auditorium or down at her legal pad. It feels impossible to calibrate a shared glance that unambiguously celebrates just the budget (and all their tiny budget-related deceptions) and not the sex (and all their tiny sex-related deceptions).

Afterward, in the lobby, she tries to duck out and get to the parking lot as quickly as possible. No chitchat tonight. But Pastor Fred cuts her off. “Sorry,” he says. “I wasn’t sure what to do back there. I hope that was okay. Was that okay?”

“Of course, it was great.”

“You’re sure?”

“More than sure.”

“Great. I just got nervous, you know?”

“Completely natural,” she says. “You did great.”

●

Art is sitting in the living room. On the coffee table in front of him: a Miller Lite and several stacks of paper.

“Meeting good?”

“Meeting good.”

“Big win for you and the khaki collaborator?”

“Big win.”

“Well, good.” He likes teasing her about Bradley, though for whatever reason he always calls him Brad. Your khaki collaborator. Your Republican partner in crime. Sometimes, when he knows they’re meeting alone together, he makes her promise not to come back transformed into a Springwater Country Club wife or reciting the virtues of lower marginal tax rates. But he’s only joking. Whenever she presses him, he reassures her: because she’s willing to work with Brad, good things are happening in the district that wouldn’t happen otherwise. Life is complicated. Getting things done is hard.

She points at the stacks of paper. “What’s this?”

“Oh, you know. Torture flights.”

She takes off her shoes and joins him on the couch. “Did you call Robert today?”

“No. I probably should have. I guess I wanted to do some of my own reading first, you know? Is that dumb? You know how they are.”

“I know how Linda is.”

“Exactly, yeah.”

“Any word from Michael?”

“Nope.”

They sit together and take turns with the printouts, reading about men kept in cells, kept awake without light, with constant light, with noise. Moved from cell to cell. Kept without clothes, without soap, without water, beaten, slapped, water poured into their lungs, locked in closets too short to stand up in, locked in coffins. Told they were about to be executed, pistols cocked behind their head, pressed up against their skulls. Hanged from the ceilings. Told their wives and children were about to be executed. Had already been executed. Been raped. Left alone for hours, days. The only sounds are Art tapping his pen against his paper, and the occasional press of the pen against the paper as he circles something or makes a check mark. At some point she gets up and makes tea.

When was the last time they read together like this?

She curls into her husband and attempts to beam a silent promise to the universe: if only everything can work out—if only she can be allowed to fix this—she will never try to get away with anything ever again. If only it can all be made to go away, she will for the rest of her life do nothing but honor and appreciate what she already has.

Before bed she emails Pastor Fred, apologizing for rushing through their conversation in the lobby and thanking him again for his support. Then she sees a new message has arrived, from a person whose name she doesn’t recognize, Eunice Larabee:

Melanie Kinston,

I had been hoping to speak to you at tonight’s school board meeting, but you left so quickly afterward. I wonder if it was because you are embarrassed by the budget you are apparently backing, you should be. I voted for you, because I wanted a real Democrat on the board to fight off these vultures who do not even believe in public ed and only join the board to keep the school down. (Also I wanted to vote for a woman too if she was qualified.) But now you are backing this crazy plan that will take sooooo much money out of the classroom and lead to more teachers leaving the state, I don’t get it. Can’t you see that when you are on the same side as a country club oldboy like Bradley Welk it is time to take a good look in the mirror? And then you don’t even stick around to listen to what real people have to say about it. I’m sorry but that just doesn’t sit with me. You can talk about compromise but you can only compromise so much. I was going to wait to write until tomorrow but I cannot sleep I am so upset so I am writing to you now. I hope you will reconsider your vote and do better going forward when it comes to listening to the real people who put you in office.

Sincerely,

Eunice Larabee

While she is reading Eunice’s email, another one arrives, this one from her son: Stop calling me.

●

For dinner with Robert and Linda, she makes pork chops and roasted potatoes. Of her five most reliable meals, this is the easiest to prepare. But it’s also Michael’s favorite, and as the smell of the cooking fills the kitchen and then the entire first floor, she regrets her choice.

“What is it?” says Art. “What’s wrong?”

“I made pork chops.” She doesn’t need to say anything else; he understands. They hold each other in the middle of the kitchen, surrounded by the heat from the oven and the smell of their son’s favorite meal.

“Did he call today?” he says.

“No.”

She is sure that Art doesn’t know—that he couldn’t possibly know and still hold her so gently.

●

How strange to see Linda and Robert’s car pull into their driveway and know that tonight, for the first time in years, they will be talking politics again.

In the foyer, Robert makes a show of cocking his head and sniffing like a curious dog. “Your chops?”

“My chops.”

He puts his hands together and tilts his head up toward the ceiling in prayerful thanks. “I didn’t dare hope.”

Mel assumes that Linda will, as soon as possible, launch right into things, peppering them with facts and did-you-knows and isn’t-it-horribles. But she’s wrong. Instead, once they sit down, Linda and Robert ask how Michael’s doing at school, how they’re doing with their empty nest. They seem genuinely curious, but Mel can’t help wondering if this was a plan they formulated ahead of time. (The scene isn’t hard to imagine: Robert counseling Linda to go easy, to not come on too strong, to remember they’re not like they used to be.) They talk about the heaviness of the drive back from Asheville. “You see it in movies and it’s a cliché,” says Art. “But then it’s your turn.”

“He’s settling in?” says Robert.

“We haven’t heard from him for a few days,” says Art. “But that must be normal. That’s normal, right?”

“Of course,” says Linda. “Of course it is.”

“We’re trying not to read into it,” says Mel.

“Good luck,” says Robert.

It ends up being Art who moves the conversation down its preordained track. “So, tell us about Atlantic Aviation.”

Robert does most of the explaining. He’s probably a good professor: the information comes efficiently and clearly, and she never feels herself in danger of losing the plot. She wonders if he and Linda agreed beforehand that he would be the one to explain. If he made her promise not to interrupt.

Springwater is the hiding place for a CIA shell corporation that transports people to torture dungeons around the world.

It pretends to be just another charter flight company.

But it’s not.

“You can call them up and ask for a flight,” Robert says, “and they just say they’re all booked.”

What he’s saying feels so strange that, coming from someone else, it might be easy to reject or doubt. But because it’s Robert, they don’t.

They learned about it from a friend, Robert says, a lawyer who does pro bono work for detainees.

“Locals sign the incorporation papers,” says Linda. “But it’s a scam. They’re just shielding the CIA.”

“What’s in it for them?” says Art.

“Who knows?” says Robert. “Some probably think it’s the patriotic thing. Or they like the excitement, maybe. I don’t know. Maybe they get paid.”

“And you’ve definitely never heard of Atlantic Aviation?” says Linda.

“No,” says Art. “Never.” He asks whether this means that any torturers are themselves living here in Springwater. This possibility had not occurred to Mel, and it moves through her like fine cracks branching out through a sheet of laketop ice.

Robert says that they don’t know for sure but they don’t think so. The evidence they have shows the flights that leave Springwater almost always make pickup stops in D.C. before heading overseas, indicating that the people living in Springwater are only pilots. “But we really don’t know,” he says. “Maybe Keith will figure it out.”

Keith, explains Linda, is the Times reporter working on a piece that will inform the public of everything they’ve been talking about. “He’s such a nice guy. He says it should run sometime in the next month.”

“We’re hoping,” says Robert, “that when the story comes out people are going to be pretty angry. And we’re hoping—”

“We’re hoping to plan an action,” says Linda. “Here, in Springwater. With your help.”

“You don’t have to say anything now,” says Robert. “Of course, you’ll want to think about it, talk about it. But—”

“Definitely,” says Linda. “Don’t decide now. But we wanted to tell you.”

Mel can’t believe she didn’t see it coming. Once upon a time, she would have known from the start. When something was wrong, you joined an action. If there wasn’t an action to join, you made your own.

“What kind of action?” says Art.

“We don’t know,” says Robert. “That’s what we want your help with.”

“Like old times,” says Linda.

Mel is surprised to feel a lump in her throat. She can see it’s the same for the others: the lump, the surprising presence of their younger selves.

Dessert: ice cream sandwiches and decaf in the living room. An ease between the four of them that Mel hasn’t felt for years. Again she prays: Let my mistakes go unpunished, and I will not make them again.

“There’s one more thing,” says Linda. “Something you should know.”

Robert has his coffee mug halfway to his mouth, and he stops it there, switches course, sets it back on the table. “Well, we’re not—”

“It’s supposed to be a secret. But just for now. We’re going to tell you, but we’re not supposed to tell you yet.”

“Not because we don’t trust you,” says Robert. “Just because… it’s complicated.”

“But,” says Linda, “I feel like we should be able to trust our oldest friends.”

Mel can tell from the look on Robert’s face that he doesn’t think it’s a good idea, but also that he knows it’s going to happen anyway. “You don’t need to tell us,” she says, though she can feel herself already anticipating the burst of shared warmth that will come from the secret—whatever it is—being pierced, its boundaries being reconfigured in real time around them.

“Oh, we’ll definitely tell you,” Robert says. “We want to tell you. We’re just not supposed—”

“I think we can tell them,” says Linda. “I think we should.”

“Well,” says Robert. “If you think so.”

“Whatever feels right,” says Art. “Don’t stress about it.”

“As long as you can promise to not tell anyone,” says Linda.

“Do you promise?”

“Promise,” she and Art say in unintentional unison.

“I mean it. Not anybody.”

“We promise, we promise,” says Art. “What is it?”

“Well,” says Robert. “It’s about this one particular person. Someone you know. Bradley Welk.”

“Holy shit, Brad?” says Art. “Is Brad one of the owners? Or the pretend owners, or whatever they are?”

Robert nods, grimacing. “On paper, he’s the president. Now, Mel, we know you’re on the school board together.”

She tells herself she’s allowed to be shocked—that what she’s hearing would count as shocking even if her interactions with Bradley were limited to school board business. The question is how shocked, exactly. How shocked would an innocent person look? “How do you know?”

“We googled,” says Linda.

“No, I mean—how do you know he’s with Atlantic?”

“His name’s right there on the papers,” says Robert.

“Jesus,” says Art. “Brad. Fuck.”

“Melly?” says Linda. “Are you okay?”

She has to say something. “Yeah. It’s just—like Art said, it’s a shock. I mean, we’ve been working all summer on this new budget plan.”

“Isn’t he a Republican?” says Linda. “We read online that—”

“That’s how things actually get passed here, you work with Republicans.”

“Of course,” says Linda, leaning over and putting a hand on her knee. “Of course. But you can keep it secret, right? Like you promised?”

“Of course,” she says. “Of course I can.”

“I knew you worked together, but I didn’t know you… worked together.”

●

By the time they leave, she’s sure Art knows. She’s terrified to be alone with him—to hear what he’ll say, what he will reveal himself to already know, or suspect, what question he will launch at her, and how she will answer.

“How you doing?” he says.

“Just… shocked.”

“It’s shocking.”

“It’s going to be hard,” she says. “To see him. It’s going to be… hard.”

“We’ll figure it out.”

“We’ll figure it out?”

“We’ll figure it out.”

●

Floss, brush teeth, gargle mouthwash. Give the sink a quick wipe.

In one of Art’s printouts, she read about men in one of the prisons, she can’t remember which prison, being forced to strip naked and masturbate together while their guards filmed.

One afternoon in the spring she drove an hour to Raleigh and found her way to a hotel whose name Bradley had sent her the night before in a text message. Right after letting her into the room, he pulled her clothes off while she was still standing, then pushed her down on the bed and told her to touch herself while he watched. No one had ever asked or told her to do that before, she had never thought about being asked or told to do that, let alone imagined how wildly alive it would make her feel to be doing it, how intensely deep inside of herself and at the same time outside of herself it would feel, the pleasure of the juxtaposition.

When exactly was it, that afternoon at the hotel? When was it in relationship to whenever the photographs—the naked men, the pyramids, the hoods—started coming out? Was it possible that because of his connection to this company, Atlantic Aviation, Bradley had somehow seen the photos before then? It was not the last time he told her to touch herself, and not the last time she did as he said.

The mental act of trying to push it all away only brings it closer, which makes her push harder, which pulls it closer.

What if Art wants sex tonight? She can only imagine it as a nightmare. Sex with her husband bleeding together with sex with Bradley bleeding together with the photographs. But if he comes asking, she doesn’t want to turn him down. Not tonight.

Thankfully, he’s already asleep. Instantly her desire to be excused from the question of whether to have sex with him is replaced by the desire for him to wake up and demand to know exactly what she is thinking, to say that he knows she’s keeping a secret, to insist on his right to know, to keep insisting until she tells him everything. But no. He stays sleeping. He’s always been a heavy sleeper. She would have to literally yell his name to wake him up, which she doesn’t think she’s going to do. And she’s right: she doesn’t.

●

This is an edited excerpt from Planes: A Novel by Peter C. Baker, which will be published by Knopf on May 31, 2022. Copyright © 2022 by Peter C. Baker. All rights reserved.

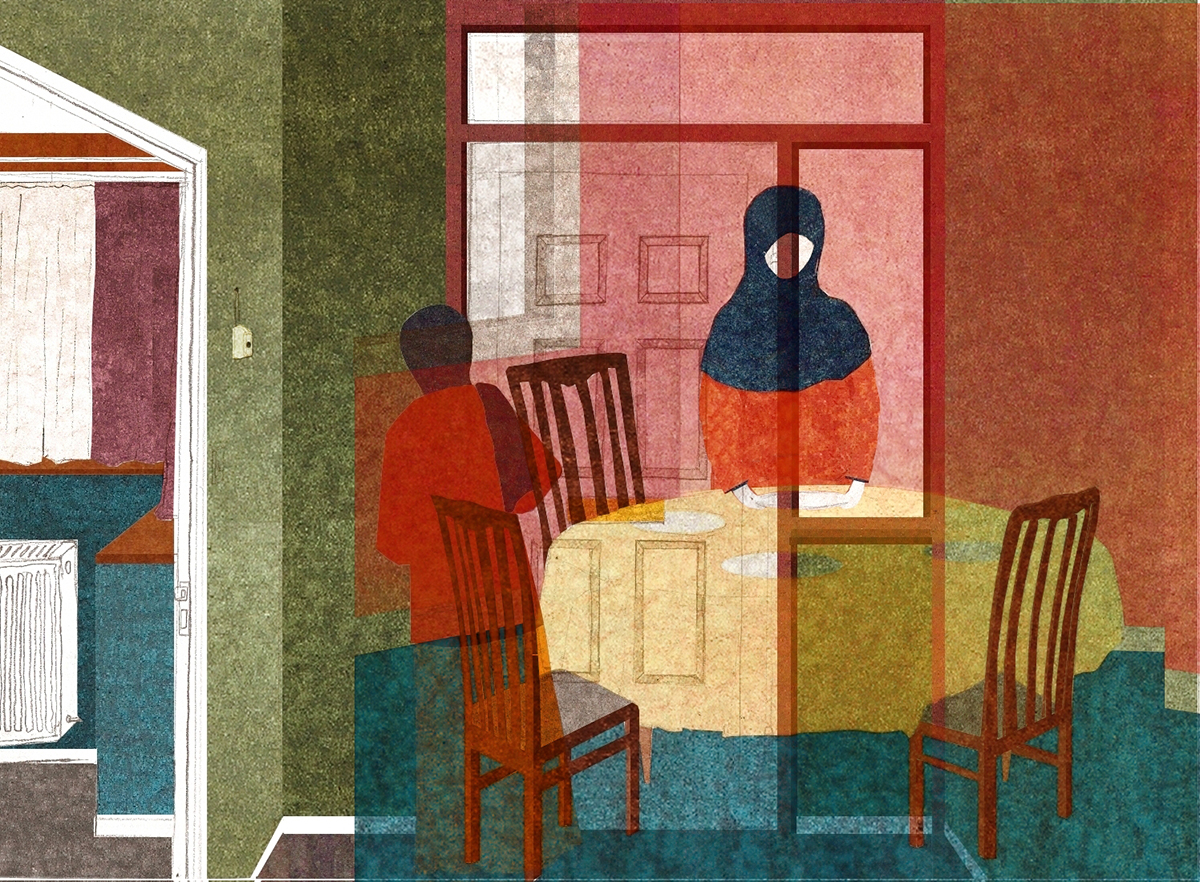

Art credit: Sofia Niazi. Image 1 and Image 2 from the Women of the War on Terror series, 2014. All images courtesy of the artist.

AMIRA

On Tuesday, after she’s walked for hours, she decides to sit at a coffee bar and order a cappuccino in her husband’s honor.

On one of their earliest dates, the third or fourth, he took her to the Appian Way Park, the Tor Marancia section. During the bus ride, and even more so once they arrived, he was visibly proud to be showing her—a native Italian—a piece of Rome she didn’t know. Afterward, they sat in a charming nearby coffee bar with outdoor seating. Even though it was already late afternoon, Ayoub ordered a cappuccino. When the waiter sniggered, she felt a mix of pity and embarrassment. But Ayoub wasn’t bothered. He couldn’t help it, he explained, he loved cappuccino too much to limit himself to having it only in the morning, the way “real Italians” did. “They can call me a dumb Arab if they want,” he said. “They can laugh. But I know I’m a dumb Arab with a delicious drink. Sorry if I embarrassed you, though.”

“No,” she said. “Not embarrassed.” Saying the words made them true. She called the waiter back and changed her order to a cappuccino. From then on, late-in-the-day cappuccinos were one of their rituals. At the coffee bar by the Appian Way Park, they became friendly with the owner, who cheered them on. “Maybe you Arabs could teach us something about being Italian,” he said. “If everyone was like you, I could sell cappuccino all day and make more money.” Arabs. Plural. They never corrected him, opting instead to smile softly at each other and enjoy the moment. Now each cappuccino she drinks alone is money she could be putting away toward rent. She knows that. But she needs to keep the ritual alive.

She’s walking home when her phone starts to vibrate in her purse. SARAH LAWYER OFFICE. It takes her more than one try to accept the call, her hands are shaking, she keeps missing the button.

They have a system. Sarah uses it with many of her clients. For most updates, she uses email. If she has information that is not urgent but, for whatever reason, cannot go in an email, she sends an email or text proposing three possible times for a call. She makes unscheduled calls only if she has truly urgent news, news she knows Amira needs to hear right away. The threshold for needs to hear right away has never been defined, and Sarah has crossed it only twice. The first time was to tell her that Ayoub seemed to no longer be in Pakistan—but that no one knew where he was, or why. The second time was two weeks later, to tell her that, apparently, he’d been held by the Pakistani secret police but was now almost definitely in Morocco. It was in this conversation that Amira first heard the words Temara Prison. Until then, she’d thought it most likely he was lying in a hospital where for some reason they couldn’t identify him, maybe his wallet had been thrown from his body in a car crash and he wasn’t yet conscious. Sarah’s system is supposed to save her clients stress by reducing the number of times they have to hold a ringing phone in their hands, suffocating under the weight of every terrible thing they might be about to learn, all the possibilities they cannot help having read about in the newspapers or online, plus all the permutations of those possibilities their minds can’t help generating. The system is also supposed to make it less stressful to check (or not check) email: one can always know that if it’s something truly urgent, Sarah will already have called.

She leans against a lamppost. Whatever she is about to learn, dozens of people walking down the street will witness her learning it.

“Hello, Khadija?” It’s Sarah, but for some reason she’s speaking English.

“Excuse me?”

“Khadija, can you hear me? It’s Sarah.”

“No, this is Amira.”

“Amira? Oh God, I’m—”

“What is it? What happened?”

“No, nothing, Amira.” She switches to her broken Italian. “It is a nothing. I’m sorry. I call the wrong number. I mean to be calling someone else. I am sorry, so sorry, very extra sorry. There is no information that is new. I am so sorry. I am… tired. I make a mistake. I am sorry.”

“Oh.” The sickening chemical collision of relief and panic in the gut.

“I am tired and I call the bad number. The not-right number.”

“That’s okay. It’s okay, Sarah. Khadija is… another client? The wife of another client, I mean?”

Sarah sighs. “Yes, the wife of a client.”

On the way home she cannot stop herself from going into the Somali internet cafe and googling: Khadija rendition wife, Khadija rendition Sarah Mayfield, Khadija CIA rendition, Khadija Guantanamo, Khadija husband Guantanamo, Khadija husband Temara. She finds nothing—nothing she hasn’t seen before, nothing specific to Khadija, whoever she is. She should stop but she doesn’t: Ayoub Alami, Ayoub Alami Temara, Arsalan Pakistan prison, Arsalan CIA detained. And so on. Until she can’t bear it.

She has an email from Mourad, Ayoub’s best friend from childhood, asking the same questions he always asks in his emails: if there is any news, if there is anything he can do, if she needs money (though he never puts it so directly), if she wants to come and stay with his family in Madrid, for any amount of time. I know Ayoub would do anything for me, and I will do anything for him.

●

When she gets home that evening, there is, for the first time in months, a padded Red Cross envelope in her mailbox. The Amira of two years ago—maybe even the Amira of six months ago—would have run upstairs right away, ripping open the envelope as she ran. But tonight she moves at a normal pace. Even when she’s inside the apartment, she takes her time, letting the envelope sit on the kitchen table while she pees, washes her face, pours a cup of water. She has accepted that the letters are guaranteed to say nothing new of substance. I miss you, I am thinking of you every day, I am looking forward to seeing you again. Sometimes I ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇ ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇ . I wonder if ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇ ▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇▇ ▇▇▇▇ .

And yet, staring at this new letter from across the kitchen, she feels the desire to rip it open building within her, pushing against her from the inside like helium against the interior skin of a balloon. She picks up the phone to call Meryem. After the last time she got a letter, she talked to Meryem about it, trying to describe the experience of opening them, how sad and tired and alone they made her feel. Meryem took her hand and told her to call the next time she got one. “I’ll come over as soon as I can,” she said. “Then you won’t be alone.”

She starts dialing but pauses halfway through. She cannot help wondering: To what extent did Meryem’s offer come from a desire to make her life more bearable? And to what extent was it about curiosity? To what extent was Meryem looking, consciously or not, for an opportunity to dip into someone else’s raw sadness, protected by the knowledge that she would soon be safely back at home with her husband and children?

She hates thinking this way. She puts the phone down and opens the letter: first the outer Red Cross envelope, then the flimsier inner one, on which Ayoub has written her address. She knows before she has the letter out that it will smell of Temara—mold, piss, shit, darkness—and knows that no matter how many times she resniffs the letter, she will be unable to tell if the smell is really on the paper or if it has been placed there by her imagination.

The letter is, like all of his letters, written in Italian. She has no way of knowing if he does this for her benefit, or in hopes of stymieing the censor. There is no indication of when it was written. It tells her nothing. It does worse than tell her nothing: it takes Ayoub—her Ayoub, the real individual—and overwrites him with an infinity of possible Ayoubs, each Ayoub changed forever by whatever he has had to endure, whatever he is still enduring (potentially right at this very moment), whatever he might yet have to endure in the future. Reading the letters makes Ayoub feel farther away. Not to read the letters would feel wrong—would, in the end, also make Ayoub feel farther away. Writing responses of any substance feels dangerous: Who knows who would read what she said, and what use they could put it to? Writing letters of no substance feels painful. Every day, no matter what she writes or doesn’t write, no matter what she does to keep their life intact, Ayoub is farther away.

She puts the letter back in its envelopes and takes it to the spare room—the room where her guests would stay if she ever had guests, and where their child would sleep if they had a child. Sometimes she misses this nonexistent child. A child would tell her what to do next: Take care of me. Each thing she did for the child would also be, unambiguously, something she was doing for Ayoub. But just as often she is sick with relief that no person is growing up dependent on her, absorbing through the air of the apartment her daily struggle to keep herself from screaming because she knows that once she starts screaming she won’t stop.

She puts the letter in the shoebox with the others, lowers herself to the floor, lies flat on her back, looks at the ceiling, and does a breathing exercise: empties her lungs by blowing out through her mouth, inhales through her nose for four seconds, holds her breath for seven seconds, empties her lungs by blowing out through her mouth…

If she had a child, this is the ceiling the child would look at every night. This is the window the child would see light coming through. The child would have no memory of Ayoub. She would show the child pictures and say, first in Italian and then in what is left of her Arabic: father.

MEL

They met in the library. After a few whispered conversations about the papers they were writing, Art asked her out. Their first date was supposed to be The Killing Fields and dinner. But on the afternoon of the agreed-upon day, he called to say that the university endowment board had just voted to continue investing its funds in South African companies. There was a sit-in happening at the chancellor’s office, and probably a march afterward. Could they do the movie next time?

She followed his directions to the imitation South African shantytown the protesters had built outside the chancellor’s office, and arrived just in time to join the march. It was obvious that Art knew people there. Until then, her own knowledge of protests was almost entirely secondhand: newspapers, magazines, TV, movies. Especially movies, which was probably why walking down Franklin Street with Art felt movie-like, every second part of an unfolding, accumulating story that their presence was revealing, to themselves and everyone watching, their bodies combining with all the other bodies to stop anything else from occupying the street other than their demand, which was suddenly Mel’s demand, too: divest! It was magic, and the magic was still there in the morning when she woke up in Art’s bed. He started taking her to speeches, panels, documentary screenings, more marches, sit-ins, letter-writing sessions, strategy debates. Apartheid. CIA meddling in South America. Nuclear proliferation. She was 21. He was 25, a grad student. They never saw The Killing Fields.

They moved together to a small wooden house on Carlson Street. The day after they moved in, Mel was unpacking when the doorbell rang. And that was how she met Linda, who was standing on her front stoop, smiling as if she already knew they would become best friends, holding a pie tin covered in aluminum foil and a brochure: “The Top Dangerous Myths of the Nuclear Lobby.”

Linda and her husband, Robert, lived just four doors down, in a small wooden house that was almost identical to theirs. That night, the four of them sat on Linda and Robert’s screened-in porch—which was the same as their screened-in porch, but with a table and chairs—eating fish tacos and drinking and talking past midnight about politics, activism, school, childhood, what they were reading, what they were learning. At least once a week for the next two years, they did it again: stayed up late sliding effortlessly from the immediate (whether so-and-so had procured the correct permit for an upcoming march) to the grand (the future they were hoping to use the march to call into being) and back again (immediate) and again (grand). Did marches work? What would this particular march actually accomplish? Should they order pizza? Who had to be up early tomorrow? Who was ready for another beer? Dinner was never just dinner, going for a walk wasn’t just going for a walk. Everything was bigger. Everything connected.

Later, when she looked back on this time of her life, what Mel remembered most was a certain easy intimacy. They stopped by each other’s houses just to see who was home. They went grocery shopping together, cooked together, ate together, marched together, locked arms on Franklin Street. They invited people over to show off what they had, the friendship they’d found. Hugging Linda and Robert goodbye at the end of an evening they’d spent together, she often felt sure not only that she and Art were going to make love once they were alone but also that Linda and Robert were, too, and that all four of them knew it but didn’t need to say anything. She and Art got married in Linda and Robert’s backyard, with Robert officiating, giving a beautiful speech about loving in history. She’d never been so happy, and never known for sure that happiness like this was actually possible for grown-ups.

Art was finishing a graduate degree in social work, tutoring undergrad psychology majors for money. Mel was halfway through a history major and working at a health food store. Robert had just started a doctorate in history. Linda was finishing a political science major and working at a garden supply center, always bringing home seeds and clippings and plants for use in their little yards. Mel sometimes suspected that either Linda or Robert had some other source of money at their disposal—but she never knew for sure.

She understood that they would leave Carlson Street someday, but she couldn’t imagine why, or when. Then Art finished his degree and struggled to find a job that put it to use. He tutored more, but found tutoring increasingly unbearable now that he was officially qualified for something else. In private, he complained to her that everyone but him was still on some kind of track. His interest in activism swung back and forth. Sometimes he seemed done with it, as if, without knowing where his own life was headed, he couldn’t marshal the energy to be interested in where the rest of the world was going. At other times, he seemed like more of an activist than any of them, as if channeling the energy he wasn’t able to pour into his career. His demeanor at protests changed, and he began—in Mel’s eyes, anyway—to resemble just slightly the people, mostly men, who showed up primarily so they could engineer antagonistic confrontations with the police. She worried, but not terribly. Everything would be normal again, she felt, as soon as he found work.

How would their life have been different if the state health department had not decided to open a new public health clinic in Springwater, serving all of Yew County?

If, when looking for the clinic’s first employees, the state hadn’t written to Professor William Townsend of the University of North Carolina School of Social Work, urging him to solicit applications from his most promising recent graduates?

If Art had never taken any of Townsend’s classes?

If he’d been offered any other job in his field?

If, in December 1985, a few weeks before her graduation, Mel had not found out she was pregnant?

At first they thought Art might commute. But the drive was an hour each way, which meant two hours away from the baby. Plus gas money. Plus paying Durham rent on a Springwater salary.