In mid-June of last year, when a million people in Hong Kong took to the streets to protest against a proposed bill that would allow for the extradition of criminals to mainland China, the government responded almost instantly with a “thanks but whatever,” and pushed ahead with its plans for the bill. Many protesters would later point to that response as a turning point—proof that their peaceful, nonviolent methods had been useless. On July 1st, protesters stormed the building of the Legislative Council. They were young, masked, audacious, but also polite: while they graffitied the walls and smashed the windows, they also took care to leave money for the cans of Coke they had pilfered from the fridge.

Eventually they released a statement with five demands. Withdrawing the extradition bill was one of them, and another was the implementation of universal suffrage in the form constitutionally guaranteed by the city’s Basic Law. The government ignored all five demands. Soon, there were protests every weekend; then every day.

As this article goes to press, Hong Kong is again in the news with Beijing seeking to pass anti-dissent national security laws; crucially, it plans to do so via the National People’s Congress, sidestepping Hong Kong’s own legislature. To Hong Kongers who care about civil liberties, this feels like the last straw. Then again, it’s been a year of many last straws. Back in June of last year, I became consumed with following the protests remotely on social media from California, where I was finishing a Ph.D. Having grown up in Hong Kong, I left in 2003 for university, typically returning about once a year. I scoured LIHKG (Hong Kong’s version of Reddit), the messaging app Telegram and, of course, Facebook. Finally, in early December, after months of watching events unfold on my laptop, I boarded a plane in San Francisco bound for Hong Kong.

At first, it seemed as if the months of protests had scarcely changed anything in my parents’ sleepy residential neighborhood in northern Kowloon. Most noticeably, the nearby mall was closed for repairs because the protesters had torched a giant artificial Christmas tree inside. (In a video posted online, broken glass crunched like snow underfoot as protesters trooped into the mall. Then, suddenly, the massive four-story tree was ablaze, and riot police were charging in to eject the protesters.) But apart from the closed mall, there was hardly any sign of the protests. The graffiti on major thoroughfares had long been painted over. Only a handful of ugly smudges remained.

The lack of visible change obscured a deep alteration. The Hong Kong I grew up in was not just apolitical but practically disdainful of politics. Hong Kongers prided themselves on being hard-nosed: just look north to China with its Communist idealism and you’d see what a blight politics could be. But since the protests had started, politics was coming up in just about every conversation, and every facet of life was pregnant with political significance. For a bite to eat you could choose between protester-friendly “yellow” restaurants and cafés and establishment-friendly “blue” ones. Some protesters were boycotting the subway over its refusal to release CCTV footage of police clashes with protesters, so taking the bus could be a political act too. And when pulling on a t-shirt in the morning, one might think twice about wearing black, the uniform of the protesters.

I. SUMMER

My habit over the summer was to wake up in California at 8 a.m.—around 11 p.m. in Hong Kong—by which point a full day’s worth of news had happened. I’d check news websites in Chinese and English, and then I’d scan LIHKG, the Reddit-like forum where protesters discuss tactics and self-described “keyboard warriors” comment on the latest developments. I’d trawl through the massive group chats on Telegram with thousands or tens of thousands of subscribers. Considered more secure than WhatsApp, the Facebook-owned messaging app used widely in Hong Kong, Telegram overflowed with memes, news and protest information.

Facebook is advertised as a place for connecting with friends, but it often feels crowded with strangers. That makes it an excellent simulacrum for the density, vacuity and callousness of the only major Chinese metropolis where it can be accessed without a VPN. Hong Kong’s density produces unsolicited levels of intimacy with people you’ll never meet again—like the two women with whom you just happen to be sharing a table at a café. You’ll inevitably overhear their conversation about in-laws and the best schools, but you’ll try to avoid their gaze.

The protesters’ tactics for organizing themselves online have been widely reported. During protests, internet chat groups provided instant updates on places where police were stationed and tear gas had been used. Protester-users could vote for their preferred strategies, both in real time and after the event, some of which would be codified by groups of more active protesters producing online flyers and other publicity materials in Chinese and English. But the internet also made more questionable tactics possible. Various threads and groups began doxxing the family members of policemen. One that I saw had published the time and location of a policeman’s wedding, encouraging users to crash it.

While most news media in Hong Kong, like most of what’s published in the city, is written in standard Chinese, posters on internet forums and Facebook often write in Cantonese. (Cantonese and Mandarin are not mutually intelligible, and they diverge markedly as to vocabulary, idiom and grammar. Standard written Chinese is based on the latter.) Since even fluent Cantonese speakers are likely to have read much more standard Chinese, the experience of reading Cantonese is a little strange. Cantonese words on a computer screen demand to be imagined as spoken words, such that as I read about the protests from fifteen time zones away, it felt as if I were being pulled into an actual conversation.

The protesters have been criticized for using Cantonese and not producing more content that’s accessible to the vast Mandarin-speaking audience on the mainland. It’s true that this choice is a tactical misstep, and it doesn’t help that the protest movement is tainted by an unseemly degree of xenophobia directed at mainland Chinese people. In mid-August, protesters at the airport beat up a Chinese man suspected of being an undercover cop; he turned out to be a journalist. As far as language goes, however, it is not entirely fair to blame the protesters for sticking to Cantonese, and using (mostly) English for reaching an overseas audience, since the biggest obstacle to reaching any potentially sympathetic mainlanders is the Chinese government’s Great Firewall, which effectively controls mentions of the protests.

The protesters’ creativity overflows online, particularly in wordplay. Hong Kong’s favorite puns capitalize on the extraordinary number of homophones that exist in all forms of Chinese. Cantonese only has several hundred possible syllables; English, by some counts, has more than ten thousand. And given that two Chinese characters that are homophones in Cantonese may not necessarily be homophones in Mandarin, some posts must be sounded out in the correct language in order to be understood. For months after the protests first started, protest slang evolved from day to day. Following it online was a little like entering a Clockwork Orange universe and getting used to Anthony Burgess’s Russian-influenced Nadsat—it was impossible to read unless you understood it, and impossible to understand unless you read it.

I used Facebook as a source of links to news websites, but what I really devoured were the comments beneath the links. Although my parents and I don’t often discuss politics, my brother and I talk often, and he still lives in Hong Kong. Whereas he and I have almost identical pro-democracy, pro-protester views, Facebook showed me comments by friends and friends of friends whose views I didn’t necessarily share. It’s common to criticize social media for offering us filter bubbles that confirm our own biases, but in this case Facebook wasn’t responsible for creating my bubble; more often, it exploded it.

For instance, I learned in November that a man ended up in the hospital in critical condition after he’d been set on fire, apparently for provoking some protesters. It goes without saying that protesters sometimes faced worse violence at the hands of the police, but even so, attacking bystanders seemed to me beyond the pale. “How about we not set useless old dudes on fire?” a pro-democracy acquaintance of mine posted. He was roundly criticized in the comments. “That guy got what was coming to him!” one person wrote. “So you can’t deal with the fact that someone finally took action?” wrote another. Eventually, the original poster added a long edit, hedging and modifying his post: he still had reservations about violence, he wrote, but only when directed at bystanders. “If a cop croaks, that’s fine by me.”

Collective decisions were made online with startling speed: thousands of people could comment on a post or vote in a single poll about protester tactics. When protests at the airport escalated, causing some flights to be canceled, protesters decided overnight to issue an apology, and the following day a small group showed up at the airport to do so. But people didn’t just organize online; they also discussed and policed the ways in which fellow protesters talked about the movement. One of the movement’s central slogans was “Don’t cut the reed mat,” exhorting nonviolent protesters not to openly condemn radical protesters in online or offline conversation. (Why “cutting the reed mat,” you ask? It turns out that it’s a reference to an apocryphal anecdote involving a second-century scholar who showed his disapproval for a former friend by cutting the mat they were sitting on in two. Hong Kong internet slang veers easily from the crude to the erudite.) The protest movement’s goal of remaining united made it hard to disagree out loud with anyone on tactics or goals, as long as they were on the same side.

As the summer wore on, the social media narrative diverged from the one available in—and I feel a little self-conscious using this term unironically—the mainstream media. On Facebook and Telegram, people were convinced that the police had killed protesters and disguised the deaths as suicides. The MTR corporation, which runs the city’s subways, refused to release video footage of a violent clash between police and protesters at a subway station, causing observers to accuse police of a cover-up. But there was never anything more than circumstantial evidence of foul play, and the allegations went uninvestigated by Hong Kong’s major news outlets. A pervasive sense of mistrust drove these theories: if there had been any foul play, people reasoned, there was no way the police would own up to it, so the lack of hard evidence didn’t really prove anything. I could never quite accept the idea that dead protesters were turning up in the ocean as apparent suicides, but when talking to friends involved with the protests, I felt sheepish about admitting my skepticism.

By September, months of ongoing protests had finally forced the government to withdraw the extradition bill. But by then, this gesture was far too little, far too late. Protesters reacted the way a fifteen-year-old might upon receiving a Lego set promised when she was eight: they made it known that they were not appeased, much less gratified. The government had ignored even the most uncontroversial of the protesters’ remaining demands: the call for an independent investigation into police brutality. The chief executive, Carrie Lam, pledged to hold a series of dialogue sessions in which she would listen to people’s concerns. The first such session was held at the end of September, and the prevailing mood was outrage. There was no second session.

II. WINTER

Hong Kong’s district-level elections were held last November, several weeks before I returned home. District elections used to be sleepy, sometimes uncontested affairs, but November’s turned into a referendum on the ongoing protests. The pro-democracy camp swept them, gaining control of seventeen out of eighteen district councils. In the wake of victory, the protests dwindled. During the several weeks I spent in Hong Kong, I almost never saw mask-clad frontline protesters dressed all in black. But police were everywhere: standing in groups on street corners, sometimes armed and carrying shields. Large-scale protests were few and far between, not least because the police had been stingy in granting the official letters that made protests legal.

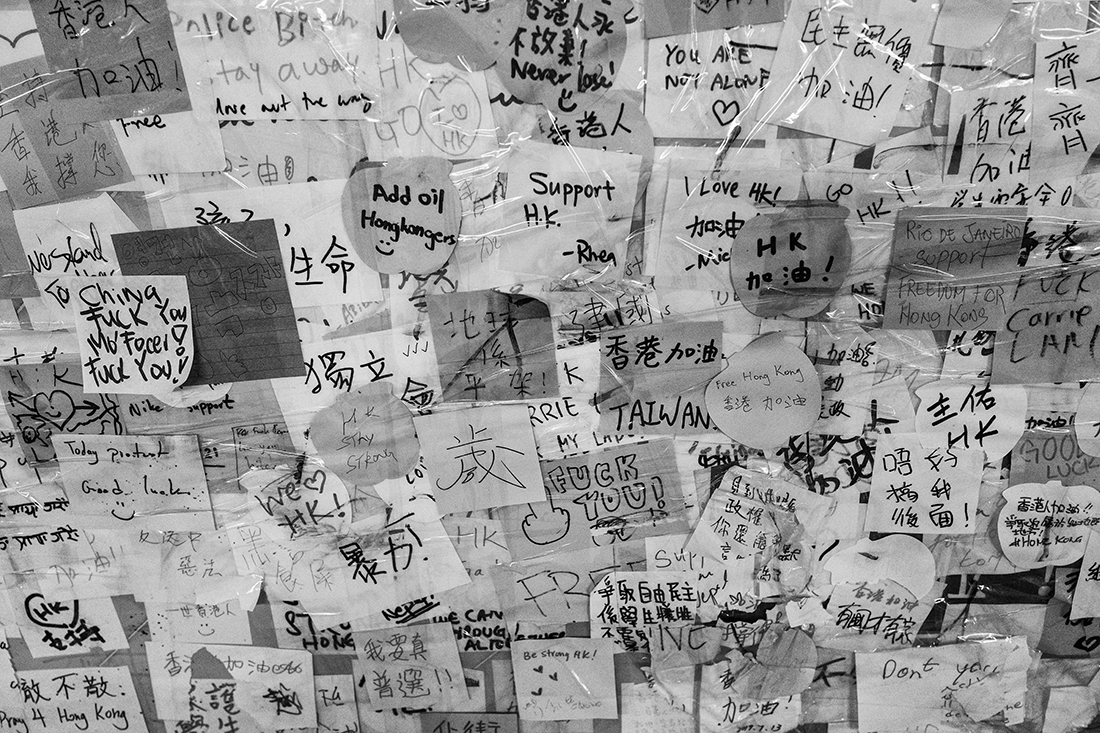

At the same time, pro-democracy protest politics were turning into something of a lifestyle choice. Many of my friends, young professionals who’d taken part in the protests, now only patronized protester-sympathetic “yellow restaurants.” Protesters reasoned that their money was best kept within a “yellow economy” that encouraged local consumption instead of depending on mainland Chinese tourism, while funneling resources back to the protest movement. Inside yellow cafés, protest slogans and diatribes against the police were scrawled on Post-it notes lining the walls, in a reference to the Lennon Wall in 1980s Prague that was covered with anti-Communist graffiti. Several apps purporting to identify yellow restaurants became popular, though some users worried that listing them publicly would expose them to retribution. Besides, what was a yellow restaurant anyway?

Once it became clear that restaurants that declared themselves “yellow” attracted waves of customers, a problem of motivation arose. Given that pro-democracy, pro-protester politics was an asset rather than a liability, an effective form of free publicity, how could one tell if a restaurant’s owners truly were pro-democracy? Some yellow restaurants had made their stance clear long before the concept of the “yellow economy” took hold, by taking part in last summer’s strikes or by offering free meals to student protesters—and in some cases, even offering them free job training. But the politics of other restaurant owners were harder to verify. Conversely, some restaurants began saying that they had been unfairly labeled as anti-protester, or “blue.” The proprietor of a café with a signature dish named after the singer Alan Tam—it apparently involves black truffles and cheese on toast—complained about watching their sales plummet after Tam came out in support of the police, despite the fact that he wasn’t otherwise affiliated with the restaurant at all.

Because of consumption-based protest activity, politics was percolating into more aspects of everyday life in Hong Kong. While I’d previously been able to take a fair stab at the views of people I knew, now they were obvious: some patronized yellow restaurants, some didn’t, and a few were staunch supporters of the protesters but unmoved by the notion of the yellow economy. It will take longer to figure out whether the division between yellow and blue restaurants is further dividing democracy supporters from their pro-establishment acquaintances and relatives.

And then there was the question of whether yellow restaurants should serve “blue,” or establishment-aligned, customers. Some yellow establishments openly proclaim that blue patrons are unwelcome. At one yellow ramen place, I noticed a sign posted above the cashier: “We’re very sorry, but as a result of the present sensitive situation we can’t serve you. Our deepest apologies!” It seemed to be a cheat sheet for the eatery’s host, offering a script for turning away potential customers—policemen, in all likelihood—without serving them. All this I had mixed feelings about: while it was legal, I didn’t see how yellow businesses could thrive if they were refusing to cater to customers whose political views differed from their own. And in Hong Kong, it’s nearly impossible to altogether avoid mainland Chinese suppliers, so any overly purist approach to establishing a yellow economy seemed doomed to failure.

But, by and large, I liked the idea of a yellow economy that would help to expand Hong Kong’s economy beyond tourist spending by encouraging locals to support independently run establishments. According to government statistics, Hong Kong welcomed more than sixty million tourists in 2018, most of them from mainland China. (Paris, for instance, was overwhelmed with forty million.) Tourism is a significant part of the economy, but it has also strained local infrastructure. When year-over-year tourist arrivals halved in November, the slowdown was palpable at major subway interchanges—the platforms were emptier, the rush for the escalators less frantic.

Yellow consumers hoped this local-first economy would blossom beyond the dining and retail sectors. The protests had lasted for months, and everyone was tired. A shift to consumption-based protest activity was allowing people to get on with their lives—buying things in shops, going out for a meal with friends—without feeling as if they had altogether abandoned their principles. But unlike ethical-consumption movements elsewhere, the yellow economy focused far more on where consumers could consider spending money than on whom they should boycott. It’s become common to observe that ethical consumption is impossible under capitalism, because each purchasing decision has ramifications that the consumer can’t know. But the yellow economy was less about disrupting corrupt supply chains than it was about directing energy and resources toward the one cause the protesters and their sympathizers did care about, with the assumption that yellow restaurants and shops would funnel their inflated profits back to the movement.

Even so, the rhythm of each day was set by the ebb and flow of ongoing protests. Last August, someone put out a call online for people to shout out slogans wherever they were at 10 p.m.: in the biggest apartment complexes, hundreds of people would chant them in the stairwells. Four months later, a lone protester was still chanting slogans outside my parents’ apartment. His voice seemed to be coming from a nearby car park or an apartment on one of the lower floors. Never having seen its owner, I imagined a young man, perhaps a lanky teenager, carrying a boombox. First he’d play a song or two. Then he’d begin: “Fight for Freedom!” Several voices in other apartments would respond: “Stand with Hong Kong!” “Five demands!” he’d cry. “Not one less!” they would reply. This typically went on for a minute or two. The man’s voice sounded hoarse, as anyone’s would be after months of shouting, but it was always punctual. On the few nights he didn’t turn up, I’d find myself improvising excuses for him.

In search of other forms of protest, I went to an exhibition of protest art in a converted industrial building occupied by arts organizations. The art, some of which was produced by local artists but much of which had been painted or drawn by protesters at the protests themselves, was largely unremarkable—watercolor on paper wasn’t really the protesters’ medium of choice. Yet it was memorable, like seeing a wild animal in a zoo, something feral and fleeting that had been captured, framed and put on walls. The building’s creaky old elevator, plastered with graffiti, stickers, posters for protest-related events and art projects, was a work of art in itself. For all that I was impressed and inspired, however, I couldn’t help feeling that I’d arrived in Hong Kong too late, having missed the spark that got this all going in the summer, the period of the pre-domesticated protests.

●

On New Year’s Day, just before I was due to leave, a march approved by the police attracted more than a million people, according to its organizers. My brother and I arrived relatively early, stationing ourselves outside Victoria Park, where it was supposed to begin—cheating, in other words, by hoping to join the march just after it started. The crowds were restless, waiting. I spotted the Buddhist colors of the Tibetan flag and some familiar stars and stripes. A steady trickle of people wandered past, apparently unaware that they were ahead of the official lead car. Finally, a large vehicle with a loudspeaker on it drove up and the crowds melted into the procession of people behind it.

Despite the fact that this would turn out to be the largest march the city had seen in weeks, the mood was subdued, as if those present felt the need to do something concrete about their political commitments, even if the energy that had driven the earlier protests had abated. Almost everyone was wearing the yellow stickers resembling Taoist talismans that the organizers had handed out, but hardly anyone had brought the elaborate handmade signs that were ubiquitous at earlier protests. Although people around us clapped politely when a caravan of people in wheelchairs drove by, the festive outrage and spontaneous slogan chanting of previous protests were absent. In fact, the crowd seemed the most exuberant when we passed a row of riot police and people hurled curses at them.

Then again, although the afternoon seemed peaceful to us, it turned out that this was mere luck—only several minutes after we had moved on, our section of the road would be teargassed. I could hear the sound of glass being smashed up ahead at what would turn out to be the offices of a state-owned insurance company. Later it would be reported that two people caught breaking the glass doors had shouted “I’m one of you!” at the riot police, who deliberately allowed them to get away. (Theories have circulated online that police had been involved in destroying property. At the very least, it looked as if the police themselves bought into the theories.)

Among the protesters, there were many older people; there were toddlers in strollers and toddlers on shoulders. Later, when reading an article about protesters rounded up somewhat randomly by the police that evening, I was struck by how many of them mentioned dinner, as though being arrested and getting a meal had become equally mundane parts of ordinary life. One person was “on his way to dinner,” another was “deciding what to eat” and a third had “asked his wife to save him dinner.” Make a politically motivated arrest of a Hong Konger, and all you will hear about, apparently, is food.

At the protest there was a marked turn toward the solutions offered by more conventional politics: the banners of newly elected district councillors were prominently raised. Politicians stood with loudspeakers at their official stands, and union reps handed out flyers. Despite having finally made it to a protest, I had the strong sense of having missed out on them. It was clear that the protests per se were no longer the movement’s center of gravity. Everyone was simultaneously bored and wary of the police; no one was yelling slogans, no one was handing out free water or face masks. Yet we were all there anyway. I walked almost to the end of the protest route and then ducked into a mall to watch the rest of the marchers go by.

Not long after I left Hong Kong in January, the first coronavirus case was reported there, and the protests evaporated. People started wearing masks on the street, then stopped going out altogether. Protest memes have long since vanished from my social media feed, replaced by photos of empty supermarket shelves. Anger over police violence turned into anger at the government’s delayed response to the spread of the virus: thousands of medical workers went on strike to protest the government’s refusal to fully close the border with mainland China.

The coronavirus hit Hong Kong hard, but it initially didn’t seem to be such a bad thing for the protests. An economic downturn that might otherwise have been blamed on activists was instead pinned on the pandemic. It has since become clear that Beijing is using the pandemic as an opportunity to crack down, arresting prominent pro-democracy figures while international attention is focused elsewhere, and now planning to pass insidious anti-protest security laws. Social distancing has meant that protesters are unable to stage any large-scale events. Still there is confidence that the pause in protests is only temporary. In 2014, as pro-democracy protest camps were being cleared by police, students put up banners that read: “We’ll be back.” With Beijing continuing to encroach on Hong Kong’s freedoms, no one even has to say that out loud.

Photo credit: Jonathan van Smit (CC BY/Flickr)

In mid-June of last year, when a million people in Hong Kong took to the streets to protest against a proposed bill that would allow for the extradition of criminals to mainland China, the government responded almost instantly with a “thanks but whatever,” and pushed ahead with its plans for the bill. Many protesters would later point to that response as a turning point—proof that their peaceful, nonviolent methods had been useless. On July 1st, protesters stormed the building of the Legislative Council. They were young, masked, audacious, but also polite: while they graffitied the walls and smashed the windows, they also took care to leave money for the cans of Coke they had pilfered from the fridge.

Eventually they released a statement with five demands. Withdrawing the extradition bill was one of them, and another was the implementation of universal suffrage in the form constitutionally guaranteed by the city’s Basic Law. The government ignored all five demands. Soon, there were protests every weekend; then every day.

As this article goes to press, Hong Kong is again in the news with Beijing seeking to pass anti-dissent national security laws; crucially, it plans to do so via the National People’s Congress, sidestepping Hong Kong’s own legislature. To Hong Kongers who care about civil liberties, this feels like the last straw. Then again, it’s been a year of many last straws. Back in June of last year, I became consumed with following the protests remotely on social media from California, where I was finishing a Ph.D. Having grown up in Hong Kong, I left in 2003 for university, typically returning about once a year. I scoured LIHKG (Hong Kong’s version of Reddit), the messaging app Telegram and, of course, Facebook. Finally, in early December, after months of watching events unfold on my laptop, I boarded a plane in San Francisco bound for Hong Kong.

At first, it seemed as if the months of protests had scarcely changed anything in my parents’ sleepy residential neighborhood in northern Kowloon. Most noticeably, the nearby mall was closed for repairs because the protesters had torched a giant artificial Christmas tree inside. (In a video posted online, broken glass crunched like snow underfoot as protesters trooped into the mall. Then, suddenly, the massive four-story tree was ablaze, and riot police were charging in to eject the protesters.) But apart from the closed mall, there was hardly any sign of the protests. The graffiti on major thoroughfares had long been painted over. Only a handful of ugly smudges remained.

The lack of visible change obscured a deep alteration. The Hong Kong I grew up in was not just apolitical but practically disdainful of politics. Hong Kongers prided themselves on being hard-nosed: just look north to China with its Communist idealism and you’d see what a blight politics could be. But since the protests had started, politics was coming up in just about every conversation, and every facet of life was pregnant with political significance. For a bite to eat you could choose between protester-friendly “yellow” restaurants and cafés and establishment-friendly “blue” ones. Some protesters were boycotting the subway over its refusal to release CCTV footage of police clashes with protesters, so taking the bus could be a political act too. And when pulling on a t-shirt in the morning, one might think twice about wearing black, the uniform of the protesters.

I. SUMMER

My habit over the summer was to wake up in California at 8 a.m.—around 11 p.m. in Hong Kong—by which point a full day’s worth of news had happened. I’d check news websites in Chinese and English, and then I’d scan LIHKG, the Reddit-like forum where protesters discuss tactics and self-described “keyboard warriors” comment on the latest developments. I’d trawl through the massive group chats on Telegram with thousands or tens of thousands of subscribers. Considered more secure than WhatsApp, the Facebook-owned messaging app used widely in Hong Kong, Telegram overflowed with memes, news and protest information.

Facebook is advertised as a place for connecting with friends, but it often feels crowded with strangers. That makes it an excellent simulacrum for the density, vacuity and callousness of the only major Chinese metropolis where it can be accessed without a VPN. Hong Kong’s density produces unsolicited levels of intimacy with people you’ll never meet again—like the two women with whom you just happen to be sharing a table at a café. You’ll inevitably overhear their conversation about in-laws and the best schools, but you’ll try to avoid their gaze.

The protesters’ tactics for organizing themselves online have been widely reported. During protests, internet chat groups provided instant updates on places where police were stationed and tear gas had been used. Protester-users could vote for their preferred strategies, both in real time and after the event, some of which would be codified by groups of more active protesters producing online flyers and other publicity materials in Chinese and English. But the internet also made more questionable tactics possible. Various threads and groups began doxxing the family members of policemen. One that I saw had published the time and location of a policeman’s wedding, encouraging users to crash it.

While most news media in Hong Kong, like most of what’s published in the city, is written in standard Chinese, posters on internet forums and Facebook often write in Cantonese. (Cantonese and Mandarin are not mutually intelligible, and they diverge markedly as to vocabulary, idiom and grammar. Standard written Chinese is based on the latter.) Since even fluent Cantonese speakers are likely to have read much more standard Chinese, the experience of reading Cantonese is a little strange. Cantonese words on a computer screen demand to be imagined as spoken words, such that as I read about the protests from fifteen time zones away, it felt as if I were being pulled into an actual conversation.

The protesters have been criticized for using Cantonese and not producing more content that’s accessible to the vast Mandarin-speaking audience on the mainland. It’s true that this choice is a tactical misstep, and it doesn’t help that the protest movement is tainted by an unseemly degree of xenophobia directed at mainland Chinese people. In mid-August, protesters at the airport beat up a Chinese man suspected of being an undercover cop; he turned out to be a journalist. As far as language goes, however, it is not entirely fair to blame the protesters for sticking to Cantonese, and using (mostly) English for reaching an overseas audience, since the biggest obstacle to reaching any potentially sympathetic mainlanders is the Chinese government’s Great Firewall, which effectively controls mentions of the protests.

The protesters’ creativity overflows online, particularly in wordplay. Hong Kong’s favorite puns capitalize on the extraordinary number of homophones that exist in all forms of Chinese. Cantonese only has several hundred possible syllables; English, by some counts, has more than ten thousand. And given that two Chinese characters that are homophones in Cantonese may not necessarily be homophones in Mandarin, some posts must be sounded out in the correct language in order to be understood. For months after the protests first started, protest slang evolved from day to day. Following it online was a little like entering a Clockwork Orange universe and getting used to Anthony Burgess’s Russian-influenced Nadsat—it was impossible to read unless you understood it, and impossible to understand unless you read it.

I used Facebook as a source of links to news websites, but what I really devoured were the comments beneath the links. Although my parents and I don’t often discuss politics, my brother and I talk often, and he still lives in Hong Kong. Whereas he and I have almost identical pro-democracy, pro-protester views, Facebook showed me comments by friends and friends of friends whose views I didn’t necessarily share. It’s common to criticize social media for offering us filter bubbles that confirm our own biases, but in this case Facebook wasn’t responsible for creating my bubble; more often, it exploded it.

For instance, I learned in November that a man ended up in the hospital in critical condition after he’d been set on fire, apparently for provoking some protesters. It goes without saying that protesters sometimes faced worse violence at the hands of the police, but even so, attacking bystanders seemed to me beyond the pale. “How about we not set useless old dudes on fire?” a pro-democracy acquaintance of mine posted. He was roundly criticized in the comments. “That guy got what was coming to him!” one person wrote. “So you can’t deal with the fact that someone finally took action?” wrote another. Eventually, the original poster added a long edit, hedging and modifying his post: he still had reservations about violence, he wrote, but only when directed at bystanders. “If a cop croaks, that’s fine by me.”

Collective decisions were made online with startling speed: thousands of people could comment on a post or vote in a single poll about protester tactics. When protests at the airport escalated, causing some flights to be canceled, protesters decided overnight to issue an apology, and the following day a small group showed up at the airport to do so. But people didn’t just organize online; they also discussed and policed the ways in which fellow protesters talked about the movement. One of the movement’s central slogans was “Don’t cut the reed mat,” exhorting nonviolent protesters not to openly condemn radical protesters in online or offline conversation. (Why “cutting the reed mat,” you ask? It turns out that it’s a reference to an apocryphal anecdote involving a second-century scholar who showed his disapproval for a former friend by cutting the mat they were sitting on in two. Hong Kong internet slang veers easily from the crude to the erudite.) The protest movement’s goal of remaining united made it hard to disagree out loud with anyone on tactics or goals, as long as they were on the same side.

As the summer wore on, the social media narrative diverged from the one available in—and I feel a little self-conscious using this term unironically—the mainstream media. On Facebook and Telegram, people were convinced that the police had killed protesters and disguised the deaths as suicides. The MTR corporation, which runs the city’s subways, refused to release video footage of a violent clash between police and protesters at a subway station, causing observers to accuse police of a cover-up. But there was never anything more than circumstantial evidence of foul play, and the allegations went uninvestigated by Hong Kong’s major news outlets. A pervasive sense of mistrust drove these theories: if there had been any foul play, people reasoned, there was no way the police would own up to it, so the lack of hard evidence didn’t really prove anything. I could never quite accept the idea that dead protesters were turning up in the ocean as apparent suicides, but when talking to friends involved with the protests, I felt sheepish about admitting my skepticism.

By September, months of ongoing protests had finally forced the government to withdraw the extradition bill. But by then, this gesture was far too little, far too late. Protesters reacted the way a fifteen-year-old might upon receiving a Lego set promised when she was eight: they made it known that they were not appeased, much less gratified. The government had ignored even the most uncontroversial of the protesters’ remaining demands: the call for an independent investigation into police brutality. The chief executive, Carrie Lam, pledged to hold a series of dialogue sessions in which she would listen to people’s concerns. The first such session was held at the end of September, and the prevailing mood was outrage. There was no second session.

II. WINTER

Hong Kong’s district-level elections were held last November, several weeks before I returned home. District elections used to be sleepy, sometimes uncontested affairs, but November’s turned into a referendum on the ongoing protests. The pro-democracy camp swept them, gaining control of seventeen out of eighteen district councils. In the wake of victory, the protests dwindled. During the several weeks I spent in Hong Kong, I almost never saw mask-clad frontline protesters dressed all in black. But police were everywhere: standing in groups on street corners, sometimes armed and carrying shields. Large-scale protests were few and far between, not least because the police had been stingy in granting the official letters that made protests legal.

At the same time, pro-democracy protest politics were turning into something of a lifestyle choice. Many of my friends, young professionals who’d taken part in the protests, now only patronized protester-sympathetic “yellow restaurants.” Protesters reasoned that their money was best kept within a “yellow economy” that encouraged local consumption instead of depending on mainland Chinese tourism, while funneling resources back to the protest movement. Inside yellow cafés, protest slogans and diatribes against the police were scrawled on Post-it notes lining the walls, in a reference to the Lennon Wall in 1980s Prague that was covered with anti-Communist graffiti. Several apps purporting to identify yellow restaurants became popular, though some users worried that listing them publicly would expose them to retribution. Besides, what was a yellow restaurant anyway?

Once it became clear that restaurants that declared themselves “yellow” attracted waves of customers, a problem of motivation arose. Given that pro-democracy, pro-protester politics was an asset rather than a liability, an effective form of free publicity, how could one tell if a restaurant’s owners truly were pro-democracy? Some yellow restaurants had made their stance clear long before the concept of the “yellow economy” took hold, by taking part in last summer’s strikes or by offering free meals to student protesters—and in some cases, even offering them free job training. But the politics of other restaurant owners were harder to verify. Conversely, some restaurants began saying that they had been unfairly labeled as anti-protester, or “blue.” The proprietor of a café with a signature dish named after the singer Alan Tam—it apparently involves black truffles and cheese on toast—complained about watching their sales plummet after Tam came out in support of the police, despite the fact that he wasn’t otherwise affiliated with the restaurant at all.

Because of consumption-based protest activity, politics was percolating into more aspects of everyday life in Hong Kong. While I’d previously been able to take a fair stab at the views of people I knew, now they were obvious: some patronized yellow restaurants, some didn’t, and a few were staunch supporters of the protesters but unmoved by the notion of the yellow economy. It will take longer to figure out whether the division between yellow and blue restaurants is further dividing democracy supporters from their pro-establishment acquaintances and relatives.

And then there was the question of whether yellow restaurants should serve “blue,” or establishment-aligned, customers. Some yellow establishments openly proclaim that blue patrons are unwelcome. At one yellow ramen place, I noticed a sign posted above the cashier: “We’re very sorry, but as a result of the present sensitive situation we can’t serve you. Our deepest apologies!” It seemed to be a cheat sheet for the eatery’s host, offering a script for turning away potential customers—policemen, in all likelihood—without serving them. All this I had mixed feelings about: while it was legal, I didn’t see how yellow businesses could thrive if they were refusing to cater to customers whose political views differed from their own. And in Hong Kong, it’s nearly impossible to altogether avoid mainland Chinese suppliers, so any overly purist approach to establishing a yellow economy seemed doomed to failure.

But, by and large, I liked the idea of a yellow economy that would help to expand Hong Kong’s economy beyond tourist spending by encouraging locals to support independently run establishments. According to government statistics, Hong Kong welcomed more than sixty million tourists in 2018, most of them from mainland China. (Paris, for instance, was overwhelmed with forty million.) Tourism is a significant part of the economy, but it has also strained local infrastructure. When year-over-year tourist arrivals halved in November, the slowdown was palpable at major subway interchanges—the platforms were emptier, the rush for the escalators less frantic.

Yellow consumers hoped this local-first economy would blossom beyond the dining and retail sectors. The protests had lasted for months, and everyone was tired. A shift to consumption-based protest activity was allowing people to get on with their lives—buying things in shops, going out for a meal with friends—without feeling as if they had altogether abandoned their principles. But unlike ethical-consumption movements elsewhere, the yellow economy focused far more on where consumers could consider spending money than on whom they should boycott. It’s become common to observe that ethical consumption is impossible under capitalism, because each purchasing decision has ramifications that the consumer can’t know. But the yellow economy was less about disrupting corrupt supply chains than it was about directing energy and resources toward the one cause the protesters and their sympathizers did care about, with the assumption that yellow restaurants and shops would funnel their inflated profits back to the movement.

Even so, the rhythm of each day was set by the ebb and flow of ongoing protests. Last August, someone put out a call online for people to shout out slogans wherever they were at 10 p.m.: in the biggest apartment complexes, hundreds of people would chant them in the stairwells. Four months later, a lone protester was still chanting slogans outside my parents’ apartment. His voice seemed to be coming from a nearby car park or an apartment on one of the lower floors. Never having seen its owner, I imagined a young man, perhaps a lanky teenager, carrying a boombox. First he’d play a song or two. Then he’d begin: “Fight for Freedom!” Several voices in other apartments would respond: “Stand with Hong Kong!” “Five demands!” he’d cry. “Not one less!” they would reply. This typically went on for a minute or two. The man’s voice sounded hoarse, as anyone’s would be after months of shouting, but it was always punctual. On the few nights he didn’t turn up, I’d find myself improvising excuses for him.

In search of other forms of protest, I went to an exhibition of protest art in a converted industrial building occupied by arts organizations. The art, some of which was produced by local artists but much of which had been painted or drawn by protesters at the protests themselves, was largely unremarkable—watercolor on paper wasn’t really the protesters’ medium of choice. Yet it was memorable, like seeing a wild animal in a zoo, something feral and fleeting that had been captured, framed and put on walls. The building’s creaky old elevator, plastered with graffiti, stickers, posters for protest-related events and art projects, was a work of art in itself. For all that I was impressed and inspired, however, I couldn’t help feeling that I’d arrived in Hong Kong too late, having missed the spark that got this all going in the summer, the period of the pre-domesticated protests.

●

On New Year’s Day, just before I was due to leave, a march approved by the police attracted more than a million people, according to its organizers. My brother and I arrived relatively early, stationing ourselves outside Victoria Park, where it was supposed to begin—cheating, in other words, by hoping to join the march just after it started. The crowds were restless, waiting. I spotted the Buddhist colors of the Tibetan flag and some familiar stars and stripes. A steady trickle of people wandered past, apparently unaware that they were ahead of the official lead car. Finally, a large vehicle with a loudspeaker on it drove up and the crowds melted into the procession of people behind it.

Despite the fact that this would turn out to be the largest march the city had seen in weeks, the mood was subdued, as if those present felt the need to do something concrete about their political commitments, even if the energy that had driven the earlier protests had abated. Almost everyone was wearing the yellow stickers resembling Taoist talismans that the organizers had handed out, but hardly anyone had brought the elaborate handmade signs that were ubiquitous at earlier protests. Although people around us clapped politely when a caravan of people in wheelchairs drove by, the festive outrage and spontaneous slogan chanting of previous protests were absent. In fact, the crowd seemed the most exuberant when we passed a row of riot police and people hurled curses at them.

Then again, although the afternoon seemed peaceful to us, it turned out that this was mere luck—only several minutes after we had moved on, our section of the road would be teargassed. I could hear the sound of glass being smashed up ahead at what would turn out to be the offices of a state-owned insurance company. Later it would be reported that two people caught breaking the glass doors had shouted “I’m one of you!” at the riot police, who deliberately allowed them to get away. (Theories have circulated online that police had been involved in destroying property. At the very least, it looked as if the police themselves bought into the theories.)

Among the protesters, there were many older people; there were toddlers in strollers and toddlers on shoulders. Later, when reading an article about protesters rounded up somewhat randomly by the police that evening, I was struck by how many of them mentioned dinner, as though being arrested and getting a meal had become equally mundane parts of ordinary life. One person was “on his way to dinner,” another was “deciding what to eat” and a third had “asked his wife to save him dinner.” Make a politically motivated arrest of a Hong Konger, and all you will hear about, apparently, is food.

At the protest there was a marked turn toward the solutions offered by more conventional politics: the banners of newly elected district councillors were prominently raised. Politicians stood with loudspeakers at their official stands, and union reps handed out flyers. Despite having finally made it to a protest, I had the strong sense of having missed out on them. It was clear that the protests per se were no longer the movement’s center of gravity. Everyone was simultaneously bored and wary of the police; no one was yelling slogans, no one was handing out free water or face masks. Yet we were all there anyway. I walked almost to the end of the protest route and then ducked into a mall to watch the rest of the marchers go by.

Not long after I left Hong Kong in January, the first coronavirus case was reported there, and the protests evaporated. People started wearing masks on the street, then stopped going out altogether. Protest memes have long since vanished from my social media feed, replaced by photos of empty supermarket shelves. Anger over police violence turned into anger at the government’s delayed response to the spread of the virus: thousands of medical workers went on strike to protest the government’s refusal to fully close the border with mainland China.

The coronavirus hit Hong Kong hard, but it initially didn’t seem to be such a bad thing for the protests. An economic downturn that might otherwise have been blamed on activists was instead pinned on the pandemic. It has since become clear that Beijing is using the pandemic as an opportunity to crack down, arresting prominent pro-democracy figures while international attention is focused elsewhere, and now planning to pass insidious anti-protest security laws. Social distancing has meant that protesters are unable to stage any large-scale events. Still there is confidence that the pause in protests is only temporary. In 2014, as pro-democracy protest camps were being cleared by police, students put up banners that read: “We’ll be back.” With Beijing continuing to encroach on Hong Kong’s freedoms, no one even has to say that out loud.

Photo credit: Jonathan van Smit (CC BY/Flickr)

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.