The threadbare historiography that we inherit as an artifact of the Cold War pits civil rights against Black Power, Martin against Malcolm, an approved and safe challenge to power versus a radical and dangerously militant one. For nearly a decade now, the research produced by the Black Freedom Studies conversations, which I help curate at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, has reexamined and challenged that narrative, focusing in particular on the way that the civil rights and Black Power movements worked together to produce the Modern Black Convention Movement, especially the “Gary Convention,” which took place in Gary, Indiana over a weekend in March 1972, four years after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and in a year that would see Nixon’s reelection as he pursued his “Southern Strategy” of realigning formerly Democratic white southerners resentful of civil rights legislation with a Nixon-led Republican Party.

One part of rethinking the civil rights-Black Power dichotomy is the new perspective on women’s leadership, including that of Coretta Scott King. King was an important thinker in the Black freedom struggle. In November 1971, in a panel discussion at the first National Conference of Black Elected Officials in Washington, D.C., she presented a paper, prepared with the help of a young Alabama political activist, Tony Harrison, titled “The Transformation of the Civil Rights Movement into a Political Movement.” The paper was the culmination of discussions that went back several years to 1968, when Martin Luther King, Jr. had begun to discuss the need for a candidate-screening process that would leverage the political power of Black America by evaluating the candidate’s civil rights and public policy records.

During the panel’s discussion period, the poet Amiri Baraka, representing Newark, New Jersey’s headquarters for the Congress of African People, spoke from the floor, endorsing King’s proposal: “That’s what I’ve been trying to say!” Immediately thereafter, King, Mayor Richard Hatcher of Gary, Indiana, Congressman Charles Diggs of Detroit, a thirty-year-old Reverend Jesse Jackson and Baraka met in a conference room to begin to flesh out plans for the first National Black Political Convention. After nearly a year of discussions, the Congressional Black Caucus had not made even one binding decision for a Black Strategy for 1972. Even worse, the process was inefficient; when workable plans were proposed and agreements reached in a series of secret summits, there was no mechanism for carrying out a decision. Thus, somewhat hesitantly—and in part because Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress,1 had embarrassed her colleagues for their political ineptitude in the face of the upcoming presidential race—the Congressional Black Caucus supported the project.

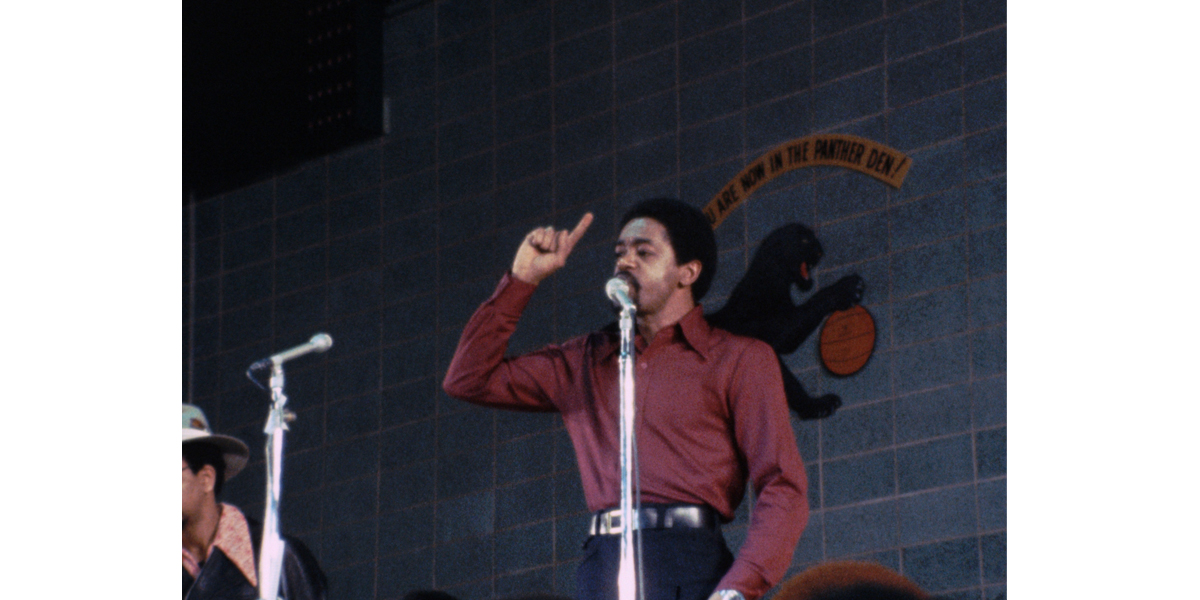

The result was the National Black Political Convention, held in Gary, Indiana on the weekend of March 10th in 1972 and commemorated in the newly refurbished documentary Nationtime—Gary, produced and directed by the pioneering Black filmmaker William Greaves. The film, like the epic event it portrayed, has often seemed like a lost chapter in the history of Black America, achieving only limited circulation in its original sixty-minute format. A few clips of Greaves’s footage were featured in the news coverage of the convention on Tony Brown’s Black Journal, and other material was featured in the second part of the classic PBS-produced civil rights television series Eyes on the Prize, which focused on the creation of Black consciousness in the Jim Crow North. A VHS version of Nationtime was screened at a Rutgers student voter-registration conference at the beginning of Barack Obama’s presidential campaign in 2008; however, the VHS was soon out of print, and the film has only now been transferred to DVD by IndieCollect as part of its restoration and re-release.

The film’s recovery is timely, not only because it comes in the midst of another period of urban rebellion in response to police violence—one of the precipitating causes of the Modern Black Convention Movement was the Newark Rebellion of July 1967, which had arisen in response to police brutality, and where Baraka himself had received a savage police beating—but also because it stands as one of the enduring achievements of Black political unity from the period. This is precisely why the Gary convention—and the film about it—was so controversial. Popular white narratives, at the time and since, have maintained that there could never be Black unity and that Black power meant anarchy; thus, a mass Black convention that united civil rights leaders and the representatives of Black Power would be impossible. Indeed, Black unity was criminalized during that Cold War era: the high crime that set the FBI onto Baraka was the possibility that he might unite the disparate elements of the movement. Hence the FBI director’s office instructed agents on October 9, 1970 to devote “aggressive, imaginative attention” to fomenting dissent between Baraka and other elements of Black leadership.

FBI and police authorities did everything in their power, including distorting news reports, to erase the steps taken toward Black unity in 1972. In that context, the National Black Political Convention—the centerpiece event in the Black Convention Movement—was too controversial to be broadcast. During the Cold War, the U.S. vied with the Soviet Union and Red China for the allegiance of the new nations in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and Latin America, which resulted in a propaganda campaign around racial equality at home. Warnings by the State Department did not silence Malcolm X and his heirs in the Black Power movement, nor did they keep the NAACP’s Robert F. Williams from exposing racial tyranny in the infamous “Kissing Case,” where two little Black boys were imprisoned for a kissing game with white girls. But Uncle Sam was more successful in frustrating documentaries. After the 1974 Sixth Pan-African Conference in Tanzania, the film footage of that summit was confiscated by U.S. customs and never returned. With the exception of Nationtime—Gary, none of the films from that important period have survived.

●

Many commentators claim that the civil rights movement diverged from Black Power following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968, but the convention bears witness to a more complicated story. On March 27, 1968, amid a whirlwind of speaking engagements building momentum for the Poor People’s Campaign, King arrived in Newark, New Jersey. In the morning King addressed an enthusiastic audience of 1,400 students and teachers at South Side High School (now Malcolm X Shabazz), sounding some of the major themes of Black Power and Black consciousness. “Now,” declared King, “I’m Black, but I’m Black and beautiful!”

That afternoon King visited Amiri and Amina Baraka in their home and headquarters, the Spirit House. Despite the striking contrasts between the political ideologies of these two leaders, the situation in the country was rapidly changing, and King was approaching key proponents of Black Power, including Stokely Carmichael and Baraka.2 Warning that the increasing divisions between Black leaders were dangerous and “counterproductive,” King spoke to Baraka about the need for a unified African American leadership. The meeting signaled the possibility for a broader Black united front, one that would include such civil rights organizations as King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). After his time with the Barakas, King addressed a packed audience at Newark’s Abyssinian Baptist Church at 224 West Kinney Street, amid the most densely populated high-rise public housing projects in the Central Ward. The people in the church cheered when King declared, “The hour has come for Newark, New Jersey to have a Black mayor!”

One week later, on April 4, 1968, King was gunned down in Memphis, Tennessee. The old Cold War interpretation of the Black Revolt concluded that Black Power died with the assassinations of King and Robert F. Kennedy, the collapse of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the hundreds of Black urban uprisings that followed King’s death. Yet it would be more accurate to say that King’s death inaugurated a new, more unified phase in the movement, one focused less on convincing whites of the moral good of integration and more on creating durable political and economic power for Blacks. During the national crisis triggered by King’s murder, the leader of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Floyd McKissick, refused to attend an emergency meeting with Lyndon B. Johnson at the White House, after observing that Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown of SNCC would not be in attendance. Similarly, Whitney Young, of the moderate, integrationist and establishment-oriented National Urban League, made a major tactical shift, putting him on the road to a Black united front with Amiri Baraka in 1970. At a press conference, Young said that he did not care about how white people felt or how sorry they were; he wanted to know what actions they would take. If nothing was done on the crisis in civil rights, housing and employment, he announced, “people like me may be revolutionists.” “There are no moderates today,” Young concluded. “Everybody is a militant. The difference is there are builders and burners.”

Young went on to become an important part of the Modern Black Convention Movement, while Baraka further developed a Black united front of “builders” with the Newark Black Political Convention, followed by the 1969 Black and Puerto Rican Convention—both precursors to the events in Gary. If the received wisdom still insists that there could have been no unity between Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, then Greaves’s documentary offers a striking visual response to the contrary, showing their widows sitting together on the stage of the Gary convention center, with about twelve thousand Black leaders and activists in attendance.

The film conveys the sometimes jubilant mood of the convention and documents many of its high points, including the controversial speeches of Mayor Hatcher and Jesse Jackson (Hatcher cautioned the delegates against acting like “timid, shivering chattels,” while Jackson declared, “I don’t want to be the gray shadow of the white elephant of one party. I don’t want to be a part of the gray shadow of the white donkey. … I am a Black man, I want a Black party”). But it can only touch on the details of agenda-building that were key to the significance of the Modern Black Convention Movement. Crucial to that agenda-building was mutual respect and reciprocal appreciation between elected officials and grassroots activists, whom the documentary stresses had rarely worked together as closely as they did in Gary. For the Modern Black Convention Movement, it was important that the priorities would come from below, meaning they would be rooted in the demands of the urban social movements that were challenging big-city political machines, including the Black Panthers in Oakland and San Francisco; the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and the Republic of New Africa in Detroit; Jitu Weusi’s organization the East and Uhuru Sasa School in Brooklyn; Baraka’s Congress of African People in Newark; and Fred Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition in Chicago. Hampton successfully achieved the “impossible” when he united the African American Black Panthers, the Latinx Young Lords and the rural white Young Patriots around a poor people’s program of free breakfast, free shoes and free health clinics. The goal of the agenda-building was to allow local organizations to develop a coherent national platform for social change and Black development. In preparation for the conference, that process unfolded in a matter of weeks, in numerous states with large Black urban concentrations.

In addition to the unified Black movement, Nationtime captures the self-confidence of that new leadership, as well as the hopes and passions of the thousands of delegates, proudly organized by state and boasting their regional banners. Greaves takes his title from the polemical poetry collection written by Baraka, It’s Nation Time, which envisioned the formation of that ensemble of Black America. “What ever we are doing, is what the nation / is / doing / or / not doing / is what the nation / is / being / or / not being,” read the first poem in the collection, entitled “The Nation Is Like Ourselves.” At the convention, “It’s Nation Time!” became the frequent slogan chanted by the delegates whenever they had to move resolutions on the Black agenda or reach some consensus. It was consistent with the convention’s focus on the autonomy of the Black American “nation” and its demand for a powerful role in shaping the country’s political infrastructure.

Baraka’s brand of Black nationalism emerged from Black Power politics in Newark, where activists had embraced Malcolm X’s subtle revisions of Black liberation, including the reinterpretation of a nationalism based on “land” to one based on controlling “urban space.” Inspired by efforts in Tanzania and Guinea, as well as urban uprisings across the United States, the Newark brand of Black nationalism, or the “New Nationalism,” emphasized a struggle to redefine urban space from ghetto to community, from internal colonialism to “liberated zones.” Building Black community institutions was thus reconceptualized as “nation-building.” If African liberation movements could build schools and health clinics amid wars against colonialism, then what excused Black Power organizations from building those institutions in Black America?

According to historian Adam Ewing, the spirit of Black nationalism can be traced back to Marcus Garvey’s “message of race unity, black pride, anti-colonialism, institution building, and self-sufficiency,” which had “generated an unprecedented mass movement across the African diaspora” for an earlier generation. In Newark, “it’s nation time” emerged specifically from the work detail of a local political campaign. Hinting that it was time to quit putting up posters late one night, one of the tired volunteers asked, “What time is it?” Baraka’s mentor responded, “It’s nation time!” In other words, it was time to get the work done. When Baraka heard about the exchange from that work detail, he crafted the epic poem equating that difficult work with the task of African nation-building.

Thus, in Black Newark this was the call and response:

“What time is it?”

“It’s nation time!”

“And what’s gonna happen?”

“The land’s gonna change hands!”

There were some difficulties with the analogy between African liberation movements and Black Power. Blacks, though often ethnically and religiously divided, were majoritarian populations on the African lands where whites had colonized and settled. In the United States, Black politics had been strategically organized around achieving autonomy and liberation in a minoritarian context where alliances and access to the white power structure remained vital. In Africa, entirely new states could and were being militarily and then politically constituted; in the U.S., taking control of the “urban space” effectively translated to a campaign to take control of local political power in the form of mayoralties. In the 1970s, Black politicians began winning these in unprecedented numbers, though the results were not always what the crowd chanting “it’s nation time!” from the convention floor in Gary might have imagined.

●

Nationtime begins with the message that many considered the convention to be a “failure,” due to the inability of the delegates to sign off on a Black Agenda. The mood and style of the documentary offers one response to this judgment. Greaves, like Baraka, was a member of the Black Arts Movement, devoted to fashioning the artistic symbols of a “liberated future,” and he interlaces his film with the poetry of Langston Hughes, the music of Isaac Hayes, the comedy of Dick Gregory and the voiceover narration of Sidney Poitier. So, too, does Greaves capture the color and excitement of the convention floor. Hatcher would later recall the diversity and intensity of the assembled:

The colorful dashikis and other African garb that some of them wore, mixing with three-piece suits and so forth. It was just an incredible sight to behold. … There was this wonderful sense that we had truly come together as a people, and a warm feeling of brotherhood and sisterhood that I’m not sure we’ve been able to duplicate since. But it was certainly there, and there was a kind of electricity in the air, and it was clear that people were there about very serious business, and really saw this as a meeting that would have a long-term, long-range impact on the lives of Black Americans.

Greaves also captures the passion of the delegates who were packed into Gary’s hotels, assembled by states so they could caucus around their floor tactics and state resolutions. The convention allowed these delegates the chance to meet people from other states and regions, an experience that often led to the discovery that what they had thought were local issues of schools, housing, social welfare and health care were in fact the national issues of modern Black America. The legendary Barbara Jordan, then an influential Democratic Texas state senator, explained that building a Black political community was an important advance on the state level: “The ongoing structure,” Jordan said, “will give Blacks in Texas this vehicle for communicating with others.” From Washington state, Republican state legislator Michael K. Ross emphasized that “the importance to us … is that we have a conduit to plug into to keep up with the national political thought of Black people.” (As may come as a surprise to many readers today, that weekend was not partisan; both Black Democrats and Republicans agreed that the development of an autonomous and structured African American political community was essential.)

Politically, the disagreements that arose in Gary have been overstated. Although the national office of the NAACP condemned the summit, many of the delegates, including those from New Jersey and Mississippi, were local branch members and leaders of the NAACP. Furthermore, the Gary Convention produced the new organization and Black Agenda that was intended. The aura of disunity captured in the film is due largely to the decision by the labor faction from Detroit’s United Auto Workers, led by the future Detroit mayor Coleman Young, to walk out on Sunday before the convention voted to establish the new organization. It has never been clear what Young’s faction wanted, other than to stall the convention and thus prevent the establishment of the new national organization that would operate outside the bounds of the Democratic Party—and as a potential rival.

The National Black Assembly (NBA) was neither in the Democratic Party nor in the Republican Party; instead, it acted as a pressure group on both parties, often running independent local candidates in municipal and state elections. In 1972, delegates from the NBA attended both party conventions. Those delegates had little influence on the Republican Convention; however, the numerous delegates from Gary at the Democratic Convention influenced the adoption of several points in the Gary Agenda. The major exception was the controversial resolution on Israel, supporting Palestinian rights. That controversy was more important than the Michigan walkout, causing several Black Democrats to leave the NBA. (In fact, that resolution was passed late on Sunday when there was no quorum, and should have therefore been void. Instead, the NBA leadership honored the vote, and needlessly stepped into some quicksand.)

The NBA remained active until after the 1976 presidential election, and its agenda was influential far beyond the arena of mainstream national politics. For instance, Black Panthers Bobby Seale and Elaine Brown ran on a similar agenda in the Oakland municipal contest in 1973, with the support of Johnnie Tillmon’s National Welfare Rights Organization and Shirley Chisholm. Before the 1972 convention, Black political representation was exceptional; however, after Gary, Black political representation soared, becoming the norm. Veterans of the Gary Convention worked both inside and outside the Democratic Party, fueling the 1984 presidential campaign of Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition. By the 1980s, one faction of the Gary veterans established the National Black United Front (NBUF), led by Rev. Herbert Daughtry and Jitu Weusi, and another faction established the National Black Independent Political Party, led by Ron Daniels, Manning Marable and Queen Mother Moore. With few material resources, Jackson came to the NBUF—of which I was at the time a central committee member—after the civil rights establishment rejected his bid for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. NBUF agreed to support Jackson as long as it could fight for its own issues in the process. Thus, Jesse Jackson rode on the back of the Black and Puerto Rican alliance established by Baraka’s Congress of African People in Newark and Fred Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition with the Young Lords and Young Patriots in Chicago, as well as similar interracial alliances from coast to coast.

●

Perhaps most relevant for 2021, the NBA launched the Stop Killer Cops Campaign as a national program of action. That was one of the busiest areas of community protest due to the rising tide of police brutality, including the surprising murder of the children of African American middle-class and professional households who believed they had escaped ghetto oppression.

But the 55-page National Black Agenda addressed much more than policing. The NBA changed the political discourse for the Black community, focusing it squarely on seven basic areas: economics, human development, communications, rural development, environmental racism, anti-colonial international policy and political empowerment. At the top of the Black agenda was the insistence that “the economic impoverishment of the Black community in America is clearly traceable to the historic enslavement of our people and to the racist discrimination to which we have been subjected since ‘emancipation.’ Indeed, much of the unprecedented economic wealth and power of American capitalism has obviously been built upon this exploitation of Black people.” The agenda concluded that there would be no full economic development for Blacks “without radical transformation of the economic system which has so clearly exploited us these many years.”

Other notable agenda items focused on the need for Blacks to control their own educational institutions (human development), to assure that “no cable television comes into our communities unless we control it” (communications), to create and protect Black home and land ownership, especially in the South (rural development), to fight back against the “atrocities of pollution” (environmental racism), to support independence movements in Africa as well as the self-determination of “Vietnam, the Middle East, the Caribbean and other places in the Third and Pan-African World” (anti-colonial international policy), and a permanent structure for the NBA to influence national elections (political empowerment). Finally, the Black Agenda addressed the specific problem of the political status denied to the District of Columbia: “The nearly 800,000 residents of our Nation’s Capital have that dual distinction of being the only citizens of our nation who are by law denied the right of self-government (the last colony) and the only major city in this country with a 72 per cent Black population,” they wrote. “These two facts are not unrelated.”

The 1972 Gary Convention generated new ways of imagining political community in Black America. A host of new vehicles, including the National Black Political Assembly with its corresponding Black State Assemblies, the African Liberation Support Committee (ALSC) with its regional branches, and the Black Women’s United Front, the Women’s Division of the Congress of African People, which developed the African Free School and the National Teacher Training Institute in Newark, all emerged from this remarkable moment.

Yet the more that Black communities built out those institutions, the greater the conflict seemed to grow between community leaders and the elected officials who promised to represent them. For the most part, the Black elected officials—like most elected leaders—resisted accountability. In 1970, Mayor Kenneth Gibson of Newark was excited to report that he was elected by a Black and Puerto Rican Convention; by 1974, Gibson made political war on the Modern Black Convention Movement. For many observers, the divisions between elected leaders and the urban Black base were the paradoxical effect of the successes of the civil rights movement—which had created class antagonisms between the growing number of Blacks able to move into the middle class and those who remained behind. By 1974, only two years after the Gary Convention, Amiri Baraka renounced Black nationalism and embraced Marxism—based in part on his recognition that skin color alone could not guarantee that a person in power would act on behalf of their people.

Nonetheless, Nationtime captures a giant step in Black liberation and delivers crucial political lessons for the next stages of the maturing Black Lives Matter movement. One thing the Gary Convention got right was to hold its summit before the Democratic Party primaries. (You cannot effectively pressure the candidates after the primaries.) By 1974 the National Black Assembly proposed what it called a “Bandung West” strategy, a summit of all the anti-racist forces, to develop a united front agenda. At its center was the African American and Latinx alliance of oppressed communities, suffering from racism. Although the strategy was hobbled by debates between leadership in the Seventies, a Bandung West Conference to develop a united strategic front would today constitute an effective continuation of the Gary spirit.

Other lessons fall outside the ambit of electoral politics. There remain burning questions today for Black America. Propelled by police brutality and the postwar urban crisis, between 1968 and 1972 there were hundreds of Black rebellions that split the country into “Two Americas.” Thus, the Gary Convention and Agenda sounded that note. However, 2020 witnessed massive urban resistance with interracial solidarity against police brutality. That expanded the horizons for today’s politics with the possibilities for a broader united front than was possible in 1972. The Gary Agenda cried out to America to solve the postwar urban crisis: instead, the urban crisis eventually was dropped from the agenda of both political parties.

Indeed, as the political scientist Ira Katznelson has noted, the political establishment defined the “urban crisis” not as educational, employment and health disasters but rather as the crisis posed by mass movements demanding change; once the mass demands stopped, the establishment concluded that the urban crisis was over.3 Their criminal negligence turned the urban crisis into the urban catastrophe. Tragically, that can be seen starkly in the city that hosted the convention, which now has one of the highest poverty rates in the country.

Yet if Gary today reminds us of what remains to be done, the Gary Agenda is a reminder of the scope and ambition of liberation politics. For today’s generation of Black leaders and activists, navigating the quicksand on the freedom road, reflecting on the Gary Agenda—as well as on what has been gained and lost since—offers a helpful starting point for addressing the dangers and prospects on the horizon.

Image credits: Stills from Nationtime—Gary, courtesy of Kino Lorber

The threadbare historiography that we inherit as an artifact of the Cold War pits civil rights against Black Power, Martin against Malcolm, an approved and safe challenge to power versus a radical and dangerously militant one. For nearly a decade now, the research produced by the Black Freedom Studies conversations, which I help curate at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, has reexamined and challenged that narrative, focusing in particular on the way that the civil rights and Black Power movements worked together to produce the Modern Black Convention Movement, especially the “Gary Convention,” which took place in Gary, Indiana over a weekend in March 1972, four years after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and in a year that would see Nixon’s reelection as he pursued his “Southern Strategy” of realigning formerly Democratic white southerners resentful of civil rights legislation with a Nixon-led Republican Party.

One part of rethinking the civil rights-Black Power dichotomy is the new perspective on women’s leadership, including that of Coretta Scott King. King was an important thinker in the Black freedom struggle. In November 1971, in a panel discussion at the first National Conference of Black Elected Officials in Washington, D.C., she presented a paper, prepared with the help of a young Alabama political activist, Tony Harrison, titled “The Transformation of the Civil Rights Movement into a Political Movement.” The paper was the culmination of discussions that went back several years to 1968, when Martin Luther King, Jr. had begun to discuss the need for a candidate-screening process that would leverage the political power of Black America by evaluating the candidate’s civil rights and public policy records.

During the panel’s discussion period, the poet Amiri Baraka, representing Newark, New Jersey’s headquarters for the Congress of African People, spoke from the floor, endorsing King’s proposal: “That’s what I’ve been trying to say!” Immediately thereafter, King, Mayor Richard Hatcher of Gary, Indiana, Congressman Charles Diggs of Detroit, a thirty-year-old Reverend Jesse Jackson and Baraka met in a conference room to begin to flesh out plans for the first National Black Political Convention. After nearly a year of discussions, the Congressional Black Caucus had not made even one binding decision for a Black Strategy for 1972. Even worse, the process was inefficient; when workable plans were proposed and agreements reached in a series of secret summits, there was no mechanism for carrying out a decision. Thus, somewhat hesitantly—and in part because Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress,11. Chisholm had unsuccessfully sought the Congressional Black Caucus’s endorsement for her presidential bid for the nomination of the Democratic Party in 1972. had embarrassed her colleagues for their political ineptitude in the face of the upcoming presidential race—the Congressional Black Caucus supported the project.

The result was the National Black Political Convention, held in Gary, Indiana on the weekend of March 10th in 1972 and commemorated in the newly refurbished documentary Nationtime—Gary, produced and directed by the pioneering Black filmmaker William Greaves. The film, like the epic event it portrayed, has often seemed like a lost chapter in the history of Black America, achieving only limited circulation in its original sixty-minute format. A few clips of Greaves’s footage were featured in the news coverage of the convention on Tony Brown’s Black Journal, and other material was featured in the second part of the classic PBS-produced civil rights television series Eyes on the Prize, which focused on the creation of Black consciousness in the Jim Crow North. A VHS version of Nationtime was screened at a Rutgers student voter-registration conference at the beginning of Barack Obama’s presidential campaign in 2008; however, the VHS was soon out of print, and the film has only now been transferred to DVD by IndieCollect as part of its restoration and re-release.

The film’s recovery is timely, not only because it comes in the midst of another period of urban rebellion in response to police violence—one of the precipitating causes of the Modern Black Convention Movement was the Newark Rebellion of July 1967, which had arisen in response to police brutality, and where Baraka himself had received a savage police beating—but also because it stands as one of the enduring achievements of Black political unity from the period. This is precisely why the Gary convention—and the film about it—was so controversial. Popular white narratives, at the time and since, have maintained that there could never be Black unity and that Black power meant anarchy; thus, a mass Black convention that united civil rights leaders and the representatives of Black Power would be impossible. Indeed, Black unity was criminalized during that Cold War era: the high crime that set the FBI onto Baraka was the possibility that he might unite the disparate elements of the movement. Hence the FBI director’s office instructed agents on October 9, 1970 to devote “aggressive, imaginative attention” to fomenting dissent between Baraka and other elements of Black leadership.

FBI and police authorities did everything in their power, including distorting news reports, to erase the steps taken toward Black unity in 1972. In that context, the National Black Political Convention—the centerpiece event in the Black Convention Movement—was too controversial to be broadcast. During the Cold War, the U.S. vied with the Soviet Union and Red China for the allegiance of the new nations in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and Latin America, which resulted in a propaganda campaign around racial equality at home. Warnings by the State Department did not silence Malcolm X and his heirs in the Black Power movement, nor did they keep the NAACP’s Robert F. Williams from exposing racial tyranny in the infamous “Kissing Case,” where two little Black boys were imprisoned for a kissing game with white girls. But Uncle Sam was more successful in frustrating documentaries. After the 1974 Sixth Pan-African Conference in Tanzania, the film footage of that summit was confiscated by U.S. customs and never returned. With the exception of Nationtime—Gary, none of the films from that important period have survived.

●

Many commentators claim that the civil rights movement diverged from Black Power following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968, but the convention bears witness to a more complicated story. On March 27, 1968, amid a whirlwind of speaking engagements building momentum for the Poor People’s Campaign, King arrived in Newark, New Jersey. In the morning King addressed an enthusiastic audience of 1,400 students and teachers at South Side High School (now Malcolm X Shabazz), sounding some of the major themes of Black Power and Black consciousness. “Now,” declared King, “I’m Black, but I’m Black and beautiful!”

That afternoon King visited Amiri and Amina Baraka in their home and headquarters, the Spirit House. Despite the striking contrasts between the political ideologies of these two leaders, the situation in the country was rapidly changing, and King was approaching key proponents of Black Power, including Stokely Carmichael and Baraka.22. King called Stokely Carmichael to ask him to attend his speech announcing his opposition to the war in Vietnam in April 1967, and Carmichael was pleased that King came to agree with the SNCC position on the war. Meanwhile, because of their Howard University connection, Carmichael frequently briefed Baraka on the internal thinking in SNCC. Warning that the increasing divisions between Black leaders were dangerous and “counterproductive,” King spoke to Baraka about the need for a unified African American leadership. The meeting signaled the possibility for a broader Black united front, one that would include such civil rights organizations as King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). After his time with the Barakas, King addressed a packed audience at Newark’s Abyssinian Baptist Church at 224 West Kinney Street, amid the most densely populated high-rise public housing projects in the Central Ward. The people in the church cheered when King declared, “The hour has come for Newark, New Jersey to have a Black mayor!”

One week later, on April 4, 1968, King was gunned down in Memphis, Tennessee. The old Cold War interpretation of the Black Revolt concluded that Black Power died with the assassinations of King and Robert F. Kennedy, the collapse of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the hundreds of Black urban uprisings that followed King’s death. Yet it would be more accurate to say that King’s death inaugurated a new, more unified phase in the movement, one focused less on convincing whites of the moral good of integration and more on creating durable political and economic power for Blacks. During the national crisis triggered by King’s murder, the leader of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Floyd McKissick, refused to attend an emergency meeting with Lyndon B. Johnson at the White House, after observing that Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown of SNCC would not be in attendance. Similarly, Whitney Young, of the moderate, integrationist and establishment-oriented National Urban League, made a major tactical shift, putting him on the road to a Black united front with Amiri Baraka in 1970. At a press conference, Young said that he did not care about how white people felt or how sorry they were; he wanted to know what actions they would take. If nothing was done on the crisis in civil rights, housing and employment, he announced, “people like me may be revolutionists.” “There are no moderates today,” Young concluded. “Everybody is a militant. The difference is there are builders and burners.”

Young went on to become an important part of the Modern Black Convention Movement, while Baraka further developed a Black united front of “builders” with the Newark Black Political Convention, followed by the 1969 Black and Puerto Rican Convention—both precursors to the events in Gary. If the received wisdom still insists that there could have been no unity between Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, then Greaves’s documentary offers a striking visual response to the contrary, showing their widows sitting together on the stage of the Gary convention center, with about twelve thousand Black leaders and activists in attendance.

The film conveys the sometimes jubilant mood of the convention and documents many of its high points, including the controversial speeches of Mayor Hatcher and Jesse Jackson (Hatcher cautioned the delegates against acting like “timid, shivering chattels,” while Jackson declared, “I don’t want to be the gray shadow of the white elephant of one party. I don’t want to be a part of the gray shadow of the white donkey. … I am a Black man, I want a Black party”). But it can only touch on the details of agenda-building that were key to the significance of the Modern Black Convention Movement. Crucial to that agenda-building was mutual respect and reciprocal appreciation between elected officials and grassroots activists, whom the documentary stresses had rarely worked together as closely as they did in Gary. For the Modern Black Convention Movement, it was important that the priorities would come from below, meaning they would be rooted in the demands of the urban social movements that were challenging big-city political machines, including the Black Panthers in Oakland and San Francisco; the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and the Republic of New Africa in Detroit; Jitu Weusi’s organization the East and Uhuru Sasa School in Brooklyn; Baraka’s Congress of African People in Newark; and Fred Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition in Chicago. Hampton successfully achieved the “impossible” when he united the African American Black Panthers, the Latinx Young Lords and the rural white Young Patriots around a poor people’s program of free breakfast, free shoes and free health clinics. The goal of the agenda-building was to allow local organizations to develop a coherent national platform for social change and Black development. In preparation for the conference, that process unfolded in a matter of weeks, in numerous states with large Black urban concentrations.

In addition to the unified Black movement, Nationtime captures the self-confidence of that new leadership, as well as the hopes and passions of the thousands of delegates, proudly organized by state and boasting their regional banners. Greaves takes his title from the polemical poetry collection written by Baraka, It’s Nation Time, which envisioned the formation of that ensemble of Black America. “What ever we are doing, is what the nation / is / doing / or / not doing / is what the nation / is / being / or / not being,” read the first poem in the collection, entitled “The Nation Is Like Ourselves.” At the convention, “It’s Nation Time!” became the frequent slogan chanted by the delegates whenever they had to move resolutions on the Black agenda or reach some consensus. It was consistent with the convention’s focus on the autonomy of the Black American “nation” and its demand for a powerful role in shaping the country’s political infrastructure.

Baraka’s brand of Black nationalism emerged from Black Power politics in Newark, where activists had embraced Malcolm X’s subtle revisions of Black liberation, including the reinterpretation of a nationalism based on “land” to one based on controlling “urban space.” Inspired by efforts in Tanzania and Guinea, as well as urban uprisings across the United States, the Newark brand of Black nationalism, or the “New Nationalism,” emphasized a struggle to redefine urban space from ghetto to community, from internal colonialism to “liberated zones.” Building Black community institutions was thus reconceptualized as “nation-building.” If African liberation movements could build schools and health clinics amid wars against colonialism, then what excused Black Power organizations from building those institutions in Black America?

According to historian Adam Ewing, the spirit of Black nationalism can be traced back to Marcus Garvey’s “message of race unity, black pride, anti-colonialism, institution building, and self-sufficiency,” which had “generated an unprecedented mass movement across the African diaspora” for an earlier generation. In Newark, “it’s nation time” emerged specifically from the work detail of a local political campaign. Hinting that it was time to quit putting up posters late one night, one of the tired volunteers asked, “What time is it?” Baraka’s mentor responded, “It’s nation time!” In other words, it was time to get the work done. When Baraka heard about the exchange from that work detail, he crafted the epic poem equating that difficult work with the task of African nation-building.

Thus, in Black Newark this was the call and response:

There were some difficulties with the analogy between African liberation movements and Black Power. Blacks, though often ethnically and religiously divided, were majoritarian populations on the African lands where whites had colonized and settled. In the United States, Black politics had been strategically organized around achieving autonomy and liberation in a minoritarian context where alliances and access to the white power structure remained vital. In Africa, entirely new states could and were being militarily and then politically constituted; in the U.S., taking control of the “urban space” effectively translated to a campaign to take control of local political power in the form of mayoralties. In the 1970s, Black politicians began winning these in unprecedented numbers, though the results were not always what the crowd chanting “it’s nation time!” from the convention floor in Gary might have imagined.

●

Nationtime begins with the message that many considered the convention to be a “failure,” due to the inability of the delegates to sign off on a Black Agenda. The mood and style of the documentary offers one response to this judgment. Greaves, like Baraka, was a member of the Black Arts Movement, devoted to fashioning the artistic symbols of a “liberated future,” and he interlaces his film with the poetry of Langston Hughes, the music of Isaac Hayes, the comedy of Dick Gregory and the voiceover narration of Sidney Poitier. So, too, does Greaves capture the color and excitement of the convention floor. Hatcher would later recall the diversity and intensity of the assembled:

Greaves also captures the passion of the delegates who were packed into Gary’s hotels, assembled by states so they could caucus around their floor tactics and state resolutions. The convention allowed these delegates the chance to meet people from other states and regions, an experience that often led to the discovery that what they had thought were local issues of schools, housing, social welfare and health care were in fact the national issues of modern Black America. The legendary Barbara Jordan, then an influential Democratic Texas state senator, explained that building a Black political community was an important advance on the state level: “The ongoing structure,” Jordan said, “will give Blacks in Texas this vehicle for communicating with others.” From Washington state, Republican state legislator Michael K. Ross emphasized that “the importance to us … is that we have a conduit to plug into to keep up with the national political thought of Black people.” (As may come as a surprise to many readers today, that weekend was not partisan; both Black Democrats and Republicans agreed that the development of an autonomous and structured African American political community was essential.)

Politically, the disagreements that arose in Gary have been overstated. Although the national office of the NAACP condemned the summit, many of the delegates, including those from New Jersey and Mississippi, were local branch members and leaders of the NAACP. Furthermore, the Gary Convention produced the new organization and Black Agenda that was intended. The aura of disunity captured in the film is due largely to the decision by the labor faction from Detroit’s United Auto Workers, led by the future Detroit mayor Coleman Young, to walk out on Sunday before the convention voted to establish the new organization. It has never been clear what Young’s faction wanted, other than to stall the convention and thus prevent the establishment of the new national organization that would operate outside the bounds of the Democratic Party—and as a potential rival.

The National Black Assembly (NBA) was neither in the Democratic Party nor in the Republican Party; instead, it acted as a pressure group on both parties, often running independent local candidates in municipal and state elections. In 1972, delegates from the NBA attended both party conventions. Those delegates had little influence on the Republican Convention; however, the numerous delegates from Gary at the Democratic Convention influenced the adoption of several points in the Gary Agenda. The major exception was the controversial resolution on Israel, supporting Palestinian rights. That controversy was more important than the Michigan walkout, causing several Black Democrats to leave the NBA. (In fact, that resolution was passed late on Sunday when there was no quorum, and should have therefore been void. Instead, the NBA leadership honored the vote, and needlessly stepped into some quicksand.)

The NBA remained active until after the 1976 presidential election, and its agenda was influential far beyond the arena of mainstream national politics. For instance, Black Panthers Bobby Seale and Elaine Brown ran on a similar agenda in the Oakland municipal contest in 1973, with the support of Johnnie Tillmon’s National Welfare Rights Organization and Shirley Chisholm. Before the 1972 convention, Black political representation was exceptional; however, after Gary, Black political representation soared, becoming the norm. Veterans of the Gary Convention worked both inside and outside the Democratic Party, fueling the 1984 presidential campaign of Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition. By the 1980s, one faction of the Gary veterans established the National Black United Front (NBUF), led by Rev. Herbert Daughtry and Jitu Weusi, and another faction established the National Black Independent Political Party, led by Ron Daniels, Manning Marable and Queen Mother Moore. With few material resources, Jackson came to the NBUF—of which I was at the time a central committee member—after the civil rights establishment rejected his bid for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. NBUF agreed to support Jackson as long as it could fight for its own issues in the process. Thus, Jesse Jackson rode on the back of the Black and Puerto Rican alliance established by Baraka’s Congress of African People in Newark and Fred Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition with the Young Lords and Young Patriots in Chicago, as well as similar interracial alliances from coast to coast.

●

Perhaps most relevant for 2021, the NBA launched the Stop Killer Cops Campaign as a national program of action. That was one of the busiest areas of community protest due to the rising tide of police brutality, including the surprising murder of the children of African American middle-class and professional households who believed they had escaped ghetto oppression.

But the 55-page National Black Agenda addressed much more than policing. The NBA changed the political discourse for the Black community, focusing it squarely on seven basic areas: economics, human development, communications, rural development, environmental racism, anti-colonial international policy and political empowerment. At the top of the Black agenda was the insistence that “the economic impoverishment of the Black community in America is clearly traceable to the historic enslavement of our people and to the racist discrimination to which we have been subjected since ‘emancipation.’ Indeed, much of the unprecedented economic wealth and power of American capitalism has obviously been built upon this exploitation of Black people.” The agenda concluded that there would be no full economic development for Blacks “without radical transformation of the economic system which has so clearly exploited us these many years.”

Other notable agenda items focused on the need for Blacks to control their own educational institutions (human development), to assure that “no cable television comes into our communities unless we control it” (communications), to create and protect Black home and land ownership, especially in the South (rural development), to fight back against the “atrocities of pollution” (environmental racism), to support independence movements in Africa as well as the self-determination of “Vietnam, the Middle East, the Caribbean and other places in the Third and Pan-African World” (anti-colonial international policy), and a permanent structure for the NBA to influence national elections (political empowerment). Finally, the Black Agenda addressed the specific problem of the political status denied to the District of Columbia: “The nearly 800,000 residents of our Nation’s Capital have that dual distinction of being the only citizens of our nation who are by law denied the right of self-government (the last colony) and the only major city in this country with a 72 per cent Black population,” they wrote. “These two facts are not unrelated.”

The 1972 Gary Convention generated new ways of imagining political community in Black America. A host of new vehicles, including the National Black Political Assembly with its corresponding Black State Assemblies, the African Liberation Support Committee (ALSC) with its regional branches, and the Black Women’s United Front, the Women’s Division of the Congress of African People, which developed the African Free School and the National Teacher Training Institute in Newark, all emerged from this remarkable moment.

Yet the more that Black communities built out those institutions, the greater the conflict seemed to grow between community leaders and the elected officials who promised to represent them. For the most part, the Black elected officials—like most elected leaders—resisted accountability. In 1970, Mayor Kenneth Gibson of Newark was excited to report that he was elected by a Black and Puerto Rican Convention; by 1974, Gibson made political war on the Modern Black Convention Movement. For many observers, the divisions between elected leaders and the urban Black base were the paradoxical effect of the successes of the civil rights movement—which had created class antagonisms between the growing number of Blacks able to move into the middle class and those who remained behind. By 1974, only two years after the Gary Convention, Amiri Baraka renounced Black nationalism and embraced Marxism—based in part on his recognition that skin color alone could not guarantee that a person in power would act on behalf of their people.

Nonetheless, Nationtime captures a giant step in Black liberation and delivers crucial political lessons for the next stages of the maturing Black Lives Matter movement. One thing the Gary Convention got right was to hold its summit before the Democratic Party primaries. (You cannot effectively pressure the candidates after the primaries.) By 1974 the National Black Assembly proposed what it called a “Bandung West” strategy, a summit of all the anti-racist forces, to develop a united front agenda. At its center was the African American and Latinx alliance of oppressed communities, suffering from racism. Although the strategy was hobbled by debates between leadership in the Seventies, a Bandung West Conference to develop a united strategic front would today constitute an effective continuation of the Gary spirit.

Other lessons fall outside the ambit of electoral politics. There remain burning questions today for Black America. Propelled by police brutality and the postwar urban crisis, between 1968 and 1972 there were hundreds of Black rebellions that split the country into “Two Americas.” Thus, the Gary Convention and Agenda sounded that note. However, 2020 witnessed massive urban resistance with interracial solidarity against police brutality. That expanded the horizons for today’s politics with the possibilities for a broader united front than was possible in 1972. The Gary Agenda cried out to America to solve the postwar urban crisis: instead, the urban crisis eventually was dropped from the agenda of both political parties.

Indeed, as the political scientist Ira Katznelson has noted, the political establishment defined the “urban crisis” not as educational, employment and health disasters but rather as the crisis posed by mass movements demanding change; once the mass demands stopped, the establishment concluded that the urban crisis was over.33. In his book City Trenches, Katznelson chronicles the way the political establishment pivoted away from the language of the urban crisis and shifted to the language of fiscal crisis, cutting budgets and programs in education, housing and youth employment. Their criminal negligence turned the urban crisis into the urban catastrophe. Tragically, that can be seen starkly in the city that hosted the convention, which now has one of the highest poverty rates in the country.

Yet if Gary today reminds us of what remains to be done, the Gary Agenda is a reminder of the scope and ambition of liberation politics. For today’s generation of Black leaders and activists, navigating the quicksand on the freedom road, reflecting on the Gary Agenda—as well as on what has been gained and lost since—offers a helpful starting point for addressing the dangers and prospects on the horizon.

Image credits: Stills from Nationtime—Gary, courtesy of Kino Lorber

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.