Jonathan Franzen is sometimes described as an important political novelist; certainly his novels can be counted on to reflect the conventional wisdom of his most likely readership. … In his latest novel, he begins in California, a fitting location to address what today’s liberals seem to view as a transnational plague of moral-political purism.

Beneath the number crunching and the medical jargon lies the conviction that AA is not just ineffective but incoherent, repellent even. In the end, the most recent skirmish in the long quarrel between AA and its “scientific” critics hinges upon a question of human agency: Can the individual really—as Glaser alleges—help herself?

The narrative of same-sex marriage asks us to believe that utopian demands led to liberal reform. On the contrary, queer utopianism clamors not for inclusion but recognition, and also negation: the rejection of the way things are.

My daughters often inquire about future womanly rites, never accepting my stated timelines for wearing earrings and bikinis and makeup. Each new day brings a new opportunity to ask again, to see if this will be the time I let them buy dress shoes with heels or wear a skirt as short and tight as those their teachers have worn. They campaign for the trappings of womanhood, knowing almost instinctively that the point of these things is their use in public—it is not enough to play with lipstick at home. What they want is to equip themselves with the accessories of feminine beauty out in the street. What they want is to be seen.

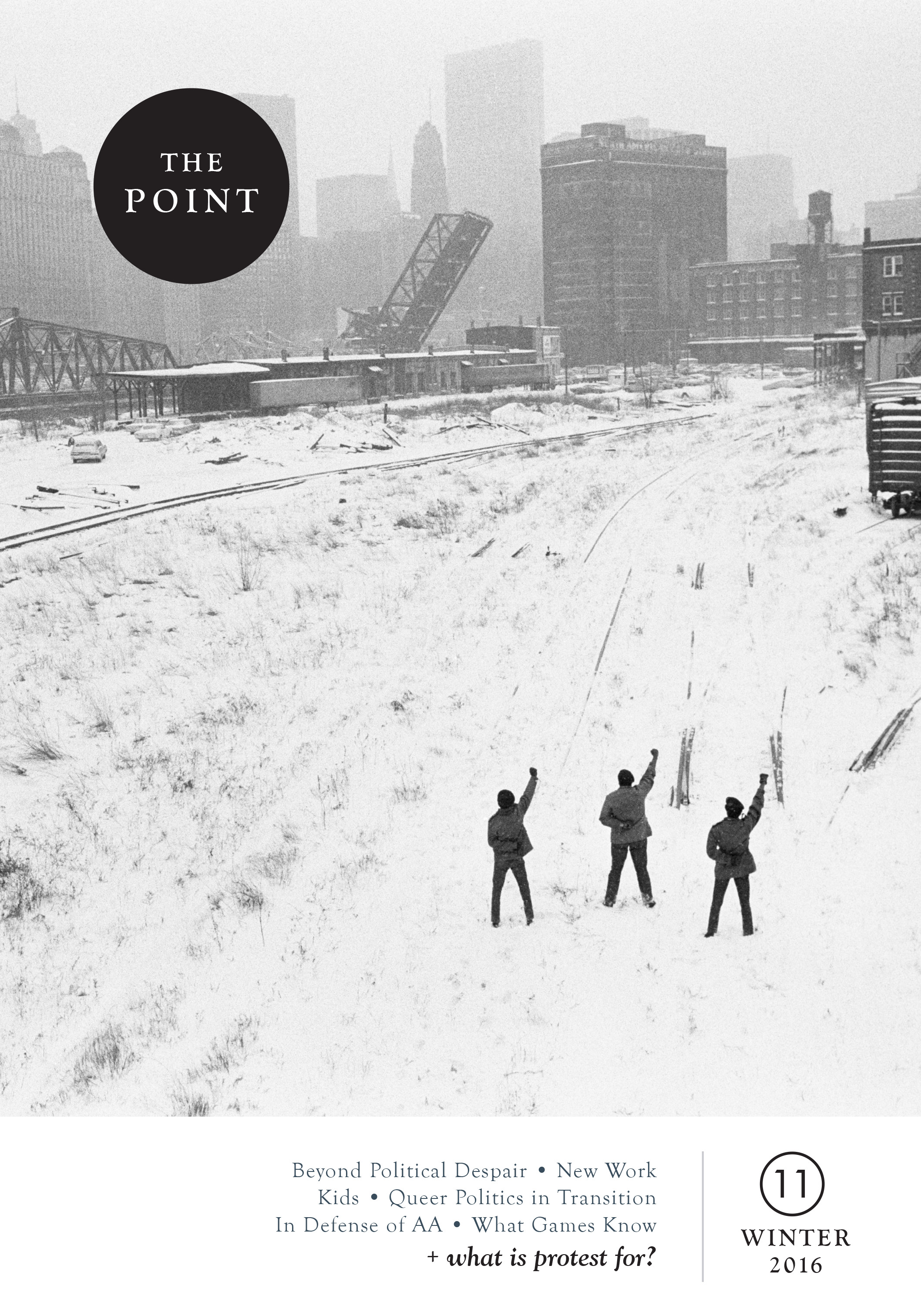

This rally had a nervous energy to it. It wasn’t led by practiced activists, just a couple of guys with rough voices taking turns with a megaphone, repeating familiar chants. I went along, certain that these calls for justice were right. As I was marching one of the few other white people there, a pale girl in glasses, approached and quietly told me that I shouldn’t hold my fist in the air—it was a Black Power appropriation, she said, wrong for a white person to use.

The world, Bernard Williams thought, is full of temptations to take simple moral views—everything from “bomb Iraq” to “maximize the good”—because the longer route of self-understanding and critique is hard, uncertain and risky. If philosophy can help us with any of this, it won’t be because it discovers a formula to replace the traditional sources of moral understanding…

Shifting my gaze back down to the dancing eyes of my oldest child, I explained that we were here for Trayvon, to uplift him, to be his hedge of protection, even in death. As we stood for Trayvon, I came to understand that we also stood for my children.

A global movement that’s strong enough to force a meaningful response to the climate crisis will need to enlist (and keep) a lot of new activists, more than any other mobilization in history. In the face of that necessity, one first step might seem obvious: stop expecting “togetherness” to feel transcendent.

We assumed that millions of young people would join us in this revolutionary movement, as they had done previously with the anti-war movement. Throughout 1969 our revolutionary faction, “Weatherman,” tried to push SDS to be more aggressive and confrontational toward university administrators and police. The main result was that students turned away from SDS; many chapters were subsequently smashed by police and university administrations, or simply atrophied and died.

When LGBT leaders cited Gandhi and King, I offered my own counterexample—the National Rifle Association’s great success in dominating policy debates about gun control, despite being in a minority on the issue in every national poll I have ever seen. As I enjoyed pointing out, especially to those LGBT activists who decried my lack of “militancy,” I have never seen an NRA public demonstration. They do not have marches.

Žižek called on the protesters at Occupy to reckon with the inevitable transition from the excitement of public demonstrations to the more sober light of the days to come—the return to a life defined more by constraint, routine and finitude. Where the carnival seems timeless, normal life is all too time-bound. Havel’s living in truth can serve as a hopeful account of living well the day after.

Desperation with regard to the possibility of effecting significant political change has led many around the world to adopt an expressive approach to politics. We proceed as if the true goal of political acts in general, and of protests in particular, is not to change political conditions but to adequately express our experience of these conditions. The relevant illusion in this case is not religious, but it is an illusion nonetheless—an illusion about political significance, whereby the fundamental political question—“What to do?”—is wrongly perceived as subordinate to the question of public appraisal: “How to appear?”

I’d grown up in the suburbs of Chicago, surrounded by people who worked exhausting, full-time jobs and who owned too much stuff and took a break and went on vacation for just a hasty, over-planned week or two each year. I didn’t want to live like that. New Work sounded great...

When Larry Clark’s film came out in the summer of 1995, I was too young to sneak into a theater. It later became a touchstone among my friends, who all watched a VHS copy together on one of the half-day afternoons when my mother made me come right home. At the time, the press hailed Kids as “raw,” “frank,” “honest” and “gritty”—all adjectives that boasted of its fidelity to the realities of kids just a little older than me. I couldn’t judge for myself since I never got around to seeing it. Watching it now, at thirty, those words still seem apt for describing something important about the film. But that something is not its realism.

amelife is part traditional memoir, part philosophical meditation on computer games. In this way it’s similar to Clune’s deservedly praised White Out, a memoir about heroin addiction that juxtaposed a traditional recovery narrative with Proustian musings on addiction and memory. But that’s where the parallels end. Clune regretted heroin, or at least was glad to have quit. He has no regrets at all about the time he spent playing computer games.

Every year, three thousand people gather in Kalamazoo for the sake of the years 400 to 1400 (approximately) of the Common Era. They come from all over the world to participate in panels like “Attack and Counterattack: The Embattled Frontiers of Medieval Iberia,” “Waste Studies: Excrement in the Middle Ages,” “Historical, Ethnical and Religious Roots of the Thraco-Geto-Dacians and Their Successors: Romanians and Vlaho-Romanians” and “J. K. Rowling’s Medievalism (I & II).” They are literary critics, historians, experts in numismatics and linguistic datasets, and nuns. There are over five hundred sessions: meetings and drinks parties and bookstalls; groups of monks dressed in black; bespectacled, serious, young men; elderly ladies in capped sleeves. Here is a ragtag bunch of human beings all on the same pilgrimage, playing a part in a story that they can’t read, because they’re in it.