Listen to an audio version of this essay:

Last summer, my grandfather mailed me a copy of the erotic novel he had written in his basement, where he also has a ping-pong table and a collection of suspiciously acquired Mexican pots. In my grandfather’s erotic novel, one of the leading women is named Elizabeth, and she is chasing a uniquely brilliant doctor, a god among men. However, the odds of her bedding him are against her. This is because: “Elizabeth stripped naked and looked at herself in the full-length mirror. ‘Just look at me,’ she wailed. ‘Wrinkled. Flat-chested.’”

Elizabeth is undressing in the company of her “maid,” whose name is Maria. Elizabeth instructs Maria to likewise disrobe so she can “see how I stack up.” Maria is a little put out, but she complies so that Elizabeth can review Maria’s “boobs” as “nubile” and “great”; also, her hips are “just great hips.” The effect is so “great” that Elizabeth opines, “If I were a man, I’d be interested in fertilizing you.”

Alas, Elizabeth says, “in a tone of melancholy,” she does not expect that her own boobs and hips will please the brilliant doctor; in fact, she muses, “nothing but a body transplant will help me stack up sexually.” Maria tries to reassure her employer. Perhaps, she ventures, Elizabeth could try to win the doctor over slowly? Perhaps, by way of her personality?

“‘Maybe that can work for you, Maria,’ Elizabeth says. ‘You get sex regularly. Me, I haven’t had a cock in me in years.’” As foreseen, Elizabeth does not get this particular cock either; regrettably, the doctor senses in her “no sense of feminine sensuality to provoke a psychological response.”

My grandfather had signed the book’s “About the Author” page. There, he wrote: “To my granddaughter, Elizabeth.”

My grandfather is my mother’s father. The book arrived with the morning mail, and I read this particular passage aloud to my mom at lunch, and we laughed. We laughed while staring at each other as if asking, Is this the correct reaction? What do you feel? What are we supposed to think? “Elizabeth,” according to the text, is “based on a real person,” but we couldn’t decide who it was supposed to be. I was a candidate, for obvious reasons, but it could also be my mom, since, historically, her dad does not have nice things to say about the way she looks. It could also be a composite character, assembled from the bodies of many disappointing women. I did not know.

I kept reading, and by dinnertime I could tell my mom that other themes in the book include: the price of malpractice insurance, the worthlessness of religion, and the tragedy that is the existence of condoms (mercifully, the book’s most appealingly svelte women absolutely disdain them). There is also:

One instance of a woman declaring, “I think we should do some kinky sex just for the sheer fun of it!”

One description of a vibrator as an “electric cunt tickler”

One hot-tub scene in which a young man’s two teen half-sisters, both naked, invite him to compare who has the nicest boobs. Delighted, he says yes: “I’ll feel your breasts simultaneously and judge the softest. That will be scientific.”

I once tried to write a college application essay about my grandfather, who is now nearly ninety. The essay was going to be about the alarming way he spoke to waitresses, which is fairly similar to how the doctor of his book addresses women, but my mom had said this was a bad idea: the admissions readers wouldn’t know what to make of him; he was way too weird. At the time, I had gone back upstairs to the family computer, reread the essay, and found that my mom was right. The essay was a mess; it was obvious that I didn’t know what to make of the man in it. Recently, I searched Amazon for the book he’d mailed to me, which was self-published. Its only review is a three-out-of-five-star rating, from someone who did not leave a comment, and who could not help me clarify what I should think.

●

My grandfather, like his protagonist, is a doctor. Specifically, he is a doctor of eyes. I know that, according to him, his parents were cruel and totally destitute. He met my grandmother in high school, and when she went to Gettysburg College, he went to work in a dynamite factory so that he could go to a nearby college, during which time he continued to date her. She was the prettiest girl at a very pretty college, the kind of place where the boys would steal the popular girls’ underwear and display the sweet little underthings outside. How embarrassing; how flattering. I have heard many times that the waistline of my grandmother’s wedding dress was 24 inches. My mom heard about this more than I did. The couple moved to New Mexico, and my grandfather stopped talking to his biological relatives. The two of them made a lot of money investing in whatever their stockbroker suggested, bought a house in the hills, kept the backyard pool at 83 degrees, became extremely preoccupied with immigration and taxation legislation, and acquired a great number of pots from a Santa Fe dealer who got them in who knows what way; the dealer is dead now.

My mom was born in 1964, and, after a dozen or so years of life, her dad began to ask if he could please buy her a nose job. My mom had her father’s nose, and it is forcefully aquiline. On a man, like my grandfather, it could be called majestic, like a wondrous mountain, the granddaddy of ski slopes, is sometimes called. My mom said she didn’t want one because she didn’t think there was anything wrong with her nose. She was a reclusive kid. She didn’t plan on becoming an actress or a model. For what did she need a made-for-television nose? At the time, my mom was a fourteen-year-old college student. Her world was divided between her parents’ house in rural New Mexico and university classrooms in which she did not quite speak the social language of her older peers. Yet, somehow, she had managed to perceive that there were worlds beyond her small one; spaces in which the size of her nose would be irrelevant to her happiness.

What did my grandfather want with a gorgeous daughter? My mom has always said that her dad was fixated on her marrying a neurosurgeon or a neuroscientist, so perhaps he thought that an alluring arrangement of facial bones would win her the correct husband. Still, why he imagined a specific profession for his daughter’s betrothed is another problem I can’t resolve. He also dreamed out loud to her that she would be an international lawyer. Also, that she would live in Paris. Actually, my mom took her biological nose to the East Coast, married a Catholic zoning lawyer and worked as a public defender. I texted my mom the other evening to ask why she thinks it mattered so much to her dad that she be what he wanted her to be, and she said, “I don’t know. You’d need a team of psychologists for that one.” Then she texted me a photo of a Greek lasagna she had baked.

One guess of mine is that my grandfather, an atheist who does not believe in afterlives, resolved that he had one life to live and that everything and everyone in it should therefore be as perfect as he can force them to be. Why not? I have a friend who is so pretty that she knows no matter how puzzling her behavior is at parties—for a while, she bit people indiscriminately—she will be rewarded with laughter, especially male laughter. But she would like to be even prettier. She told me on the phone, after an appointment that elongated her eyelashes, which followed an appointment that landscaped her eyebrows, that she had resolved to get a nose job. I said, Why? What’s wrong with your nose? And she said it was a little asymmetrical. I said, “But you’re already hot enough to get everything you ever need, and probably everything you want.” And she said, “What does that even mean, though?” What does it mean that she is hot “enough”? It seemed to her like, if the option is available to live as a very hot person, it is a form of deprivation to live any less hot of a life. I once read that people are most ornery about the income bracket just above theirs, which means that the extremely rich envy the extraordinarily rich.

Another friend of mine has a friend who is so pretty that restaurants pay for her to eat dinner inside them so that other patrons will perceive their dining experience as more rarefied. Before she met that friend, she told me, she didn’t even know that this next level of pretty privilege existed; when my friend found out, though, she didn’t particularly care. Because she seems phenomenally well-adjusted, I asked her how her mom talked to her about beauty, and she said, basically, her mom had banned all talk about prettiness or lack thereof. It was not a subject that she had grown up thinking much about. My mom didn’t talk about looks much either, yet somehow I spent a lot of my own teen years in front of H&M’s circular mirrors, assessing my nose from different angles while my mom waited outside the dressing-room curtain, inquiring as to when I was going to come to a conclusion; about the jeans, she meant.

The nose on my face is sort of like my mom’s nose, albeit softened by my dad’s nose, which is a bunny hill of a nose, gentle and unlikely to injure. The result, on me, is a perplexingly irregular creation. When I told my dad I hated it we were in the car, coming home from ballet class, and I was thirteen. He said, “Don’t you think that beauty standards are changing?” I cried and told him he was extremely wrong about that. Or at least, I explained, no one had conveyed this cultural change to the guys at school, or my ballet classmates, or, as far as I could discern, anyone outside this car; people seemed rather unaware that my nose was to be admired.

And I did want to be admired; specifically, I wanted for the things I said to be blessed with the worthiness that, so it seemed to me, is automatically conferred upon words that swoon out of lovely lips set beneath lovely noses. In middle-school art class we had to paint either a favorite quote or an original phrase as calligraphy. I decided to write my own phrase, so what I painted was: “Some see the blue jay, but never the sparrow.” This was before Facebook, so it was before it was possible to humiliate yourself by posting oblique and mopey song lyrics as your “status.” Instead, I aired my grievances in gigantic cursive, which was taped for all to see on the hallway’s white cinder block.

Two years later, I found myself doing a rendition of the “Cha-Cha Slide” dance one night behind an older guy from math class. It was a mutual friend’s birthday. We stepped to the right and stepped to the left and cha-cha-ed real smooth. This guy was very enthusiastic with his cha-cha. The mutual friend and I went to ballet school together, and we both had tiny, well-regulated hips, and we giggled at his rambunctious ones. We giggled harder when he asked if I’d like to dance. He was hot; I giggled, and declined, not because I didn’t want to dance, but because I was still embarrassed by attraction. The next morning in class, he tapped me on the shoulder and showed me the puckered cuts on his forearms. He said, “I did this because of you.” I was stunned. I was stunned with guilt, stunned by having hurt someone so blithely; but mostly I was stunned with joy. I was absolutely delighted that my judgment mattered to him. All along I thought I’d wanted to just be seen, but what I’d really wanted was to be seen doing the seeing. I was a hot girl. A mean one. But still—hot.

Wait, wait—was I actually hot? Another plot point in the encounter with the cha-cha dude is that, for the rest of the year, he conducted a war of math-class-based revenge: pulling my hair, writing on my neck in pen and tapping on my head with his pencil. It was the kind of indignity that I knew he would never commit on any actually hot women, who were by then intimidatingly ensconced in red cheerleading outfits. Years later, still wondering what species of bird I was, I looked up on Reddit how people know whether they are hot or not. One option, apparently, is to be so unimpeachably pretty that the world just hammers it into your head that you’re definitely attractive. “I’ve always been told that I was pretty, I modeled as a kid … I catch myself in the mirror and think, ‘damn girl, you beautiful,’” writes one alleged human being. Another is to post to the r/AmIHot subreddit and ask anonymous people if you have it going on (this, I guess is the virtual equivalent of undressing in front of “your maid” Maria). Still, people there will probably give you contradictory assessments. If you are clawing for a clarifying answer, and not just to be reassured that someone out there would like to sleep with you, this might be unsatisfying. So, one last solution, according to other people on Reddit, is this:

“I just feel like I am. I wake up and am happy with myself. I wear minimal make up that compliments me and dress nicely. It’s a great attitude to have rather then [sic] trusting what others say!”

“Realistically I’m probably average and I’m never going to be Kate Moss, but I don’t care. I don’t ask people whether I’m pretty, I just look in the mirror, tell myself that I am and walk out the door.”

“I think I’m attractive. Therefore, I am.”

Is it possible to just decide that you’re hot? To declare yourself impervious to judgment? And just roll with that? I have a therapist now who loves to solve things. When I told her that I’m often very tired, she said I could avoid that if I stopped eating gluten and soy. When I told her that I still worry sometimes about whether I’m beautiful or not, she said, “Don’t worry. You are.” Well, all right. My boyfriend has a daughter, and she is two, and, ideally, he hopes that she will find herself beautiful. But he has also lived among humans for three decades, so he knows that life is full of mirrors that are at all times reflecting back to us images of ourselves that sometimes are not what we see, or what we want others to see. He also knows that what we see in those mirrors matters; that the images in them reach out and touch us. One thing he remembers from Catholic high school is that the hottest girl, the one whose name was spoken in reverence, and who was tiny and haloed in blond hair and sweetness, showed up at boy’s poker night, opened her purse, and produced a Bud Light. She popped the beer open. Nobody said anything. Nobody said anything, even though all the boys were terrified that the host’s parents would come into the living room, see the beer and yell. Nobody said anything, even though God Himself would be mad at them.

When I was young, and even now, with my twenties having just concluded, it was not particularly relevant to my quest to be cute that I knew contemporary beauty standards to be racist, ageist, classist, ableist, fatphobic and transphobic. Also, that they were, and are, misogynistic. That they are an invention of people trying to sell me creams, pills, underwear, magazines, etc. That they are totally antithetical to the shape that many healthy female bodies yearn to take. That they do not help the world. Nor does it really matter to me that a less-than-adorable childhood meant that, because people were not watching me, I could watch them; that I could learn in peace what people needed from me—which was, generally, to offer back to them confirmation of their own beauty. I would trade that education for a lifetime of prettiness. Because none of these facts change what has been true for me: that it is easier to be a hot girl opening an illicit Bud Light than it is to be a girl opening that beer without the protection of good looks. That those who are thin enough, and fine-featured enough, and blond enough, and clear-skinned enough, and tall enough but also short enough, and hot enough, wear the humiliations of life a little lighter than do the rest of us.

●

Before my grandfather wrote an erotic novel, he had self-published a coffee-table book on his large collection of pots. In it, he reported that he was the first to decipher their symbols, which, he said, primarily depict Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec god for whose pleasure humans once sacrificed beautiful creatures, like children.

The pots in my grandparents’ house were made about seven hundred years ago, by the people who once lived in Casas Grandes, a region in Mexico’s Chihuahua state. Most of them are white and round, with black-and-terra-cotta-colored geometrics; others are shaped like human figures, with protruding bellies, small feet and painted expressions that might just as well be surprise as longing or joy or devastation. Not long ago, I emailed the anthropologist Christine VanPool to ask if she could help me make sense of my grandfather’s book on the pots—if she could tell me what to think about at least one of his books—and she wrote back that yes, she would be delighted to talk about the book, though, she cautioned, some of his ideas “are challenging to evaluate.”

In 2003, a year after my grandfather self-published his book, VanPool finished her thesis at the University of New Mexico on the same pots. On the phone, she told me that a lot of his book’s conclusions about what the pots’ symbols meant were consistent with general truths applicable to cultures throughout the Southwest and Mesoamerica. For example, according to VanPool, the deity on many of the pots, whom my grandfather called Quetzalcoatl, is not exactly Quetzalcoatl, but probably is indeed a version of the Quetzalcoatl-like being that appears in variations across the region’s ancient cultures. Where my grandfather likely started going wrong, she explained, was when he called pots shaped like voluptuous women “goddesses”: like, the goddess of “female sexual power”; or the goddess that he said represented both “benevolence and debauchery.” They were probably not goddesses, she suggested, but women who had once been very much alive: “Each one is probably an actual female,” she said. “Who had a name. Who had a sense of person.”

The peoples of Casas Grandes are unusually inscrutable to us now. They were, and are, a borderland people. Back then, they were north of the Maya, south of the Apache. Now, they are in between the pyramids and pueblos, which attract much more scholarly attention. No one knows any more where the Casas Grandes peoples came from or what happened to them; we don’t know what language they spoke or what they called themselves. Anyway, VanPool said, she’d had lunch with my grandparents twenty years ago, in Albuquerque. It was a long and lovely conversation, she said, and, while she had promised to keep in touch, her first child was born shortly thereafter, and she had never followed through.

Oh actually, VanPool said, before hanging up, on second thought, maybe my grandfather was inadvertently right that the women figures were goddesses. Apache-speaking peoples, who lived contemporaneously with the Casas Grandes peoples in what is now the American Southwest, believed that when a girl transitioned into womanhood she became, briefly, the original woman who gave birth to mankind, by way of sleeping with the Sun and the Rain; the deity is sometimes called the Changing Woman. Perhaps, VanPool said, the peoples of Casas Grandes had believed the same. Perhaps their artists had captured the girls right at the moment of deification. VanPool has no idea, she said. She has no idea how these women grew up; no one does. And she has no idea how an artist might wish to represent them: Which women were worthy of committing to ceramic? At what moment in their lives?

Later, I googled the Apache rite, which is still practiced, and read a 1966 oral history of the Cibecue Apache, of Arizona, in which one father says that his daughter didn’t want to do the ceremony, both because “she was bashful” and because the ritual was old-fashioned and “her friends would tease her.” The girl didn’t believe that she had to embody the Changing Woman—which required dancing for several days straight in the August sun—in order to have whatever kind of womanhood she desired. The father says:

So my wife talked to her, but she didn’t change her mind. My wife and my wife’s parents were sure mad. We never had the dance. It wouldn’t be good to make her have the dance if she didn’t want it.

Recently I went for a walk with a friend, and I told them that I was thinking about how to protect a child from a world that might insist to her that she should look a very specific way; a look that might be painful to attain or maintain, or which could be unattainable or unsustainable. My friend had left behind the Mormon Church as a teen, and later, the gender assigned to them at birth. They pointed out that a kid might have no interest in being “hot” as I imagine “hot” to be, or “perfect” as my grandfather imagines “perfect” to be. This child might be repulsed by conventionality. Perhaps they will desire to stand out, and perhaps, if they get a big beak between their eyes, they will adore it. Maybe, the eyes that I sought on my own body will mean nothing to them; maybe, the judgment of a heteronormative-straight-cis-white-high-school-dude might land on them without impact. I was ashamed that these were not the first thoughts that arose in my own mind, when imagining what life would be like for my boyfriend’s child, or for a hypothetical child of my own. Of course the world in which they grow is growing too; of course it is growing in what it finds right and beautiful and worthwhile. Of course a child might want to look different than their parents wanted to look; of course they might not want to dance.

Yet I am still dancing. While I’d like to say that I now feel most beautiful dancing with my boyfriend’s daughter, wildly and fully and grandly, in hopes that she will learn to treat her body as her home, and as a home that is ostentatious with joy—this is not the truth in full. Because of course it still matters to me that when my boyfriend reaches out for me, to join me in my dance, the waist he touches is small.

●

For a little while, my mom had wanted me to have a relationship with my grandparents because that was the normal thing to do. She had met her father’s mother just once, in a hotel, and then never again. She knew almost nothing about her besides one anecdote, in which my grandfather saved up enough money to buy an ice cream, and then his mom took it from him and ate it herself. My own grandparents took me on vacation when I was about twelve. My grandpa called my grandma “Toots.” I asked if I could wear her lipstick, and she said no because the stick had grooved to the shape of her lips, after many, many years of applying it. She didn’t want to mess it up. At dinner, my grandfather said that if I grew up to be beautiful, I would attract a man who would take care of me, and who would take me to fine restaurants like this one. He was sure, he said, that my own dad hoped for the same salvation for me, even if he was too lefty to say so.

At night, my grandfather required that I let him put Neosporin on my acne, because, he said, it was better than all the creams on the market; doctors know best. I was embarrassed that he had seen my pimples, which I’d thought I was doing a good job of covering up with Maybelline, and so I sat next to him on the hotel bed and let him fix me. My mother had had the same issues with her skin, he said, but she had never let him help her. She was very stubborn that way, he said. Recently, I wondered out loud to my boyfriend, who gets along beautifully with everyone, if the best parents might be the people who just basically love all people, since parents universally have absolutely no idea what sort of person they are going to get.

When I was in high school, there was a months-long period during which my mom and her dad got along. He had gotten colon cancer and had become interested in God, and in God’s paradise, which meant that he had also become interested in living the earthly life that is prerequisite to spending the hereafter in the more beautiful of the two choices. When he went into remission, the two of them fell out again, and the most recent time I saw my grandparents was at a sort of truth-and-reconciliation-style dinner two years ago, at their house. It was New Year’s Eve, and my grandmother hobbled around the kitchen trying to put together a beef stroganoff. I held her hands, trying to help her get between the refrigerator and the stove, and my grandfather apologized to the table for her “gimpy” leg. In reply to inquiries, he assured the younger generations that she did not need a wheeler, because, as we could see, she gets around just fine. My grandmother said this was true and that her health was great, thanks to my grandfather, who, because he is a doctor (of the eyes), takes good care of her.

My grandfather uncorked French champagne (he only drinks French wines). He talked about his interests in child development and zoning laws, and he talked about his surprise that his wife, who had recently had a 23andMe test, did not turn out to be part-Portuguese, because she had such lovely olive skin. He remarked that my mom had done a nice job staying thin. He wanted to know if I had a boyfriend. I did; that boyfriend (not my current partner) was much older than me and had a nice office at a hedge fund, and my grandfather said this was wonderful, just like my figure. Eventually my mom got up and went into the den to scroll the New York Times website on her phone, because she was tired of hearing what her father had to say about anything.

There are limits to how much you can influence your children, and sometimes these limitations are tragic. It has made no difference to me, as an adult, that when I was little my mom didn’t wear makeup or fix her hair, that she didn’t give a damn about Pilates or what models ate for breakfast, and that she hoped, very much, that I would be like her; that I would not worry so much about what was on my face, which is so impermanent, no matter how lovely or not. I still grew up envious of the girls beside me in ballet class, whose parents bought them new noses for the stage; I still grew up wrapping a tape measure around my waist to make sure it never exceeded 24 inches. It also may not make any difference that my boyfriend’s daughter will grow up with a dad who hopes so badly that she will love her body, without maligning it or torturing it. She, like me, might discover that the tenderest, or the most fearless, or the most morally admirable princesses on television are also conventionally beautiful; she might also grow up to ask other people what she should think about her body. Or maybe, as with my mom and her parents, the limits to how much the adults in this child’s life can influence her, can pass on to her their own inheritances, will be a gift.

There are also limits to how much a person can forget their parents. Take, for example, a child who did not feel loved by his parents, and who grew into a man who did not know how to love a daughter. Take my grandfather. One fact about the Changing Woman is that she is said to endlessly walk the earth eastward, round and round, aging and aging, until she comes upon her young self again, merges with it and becomes young again; then she keeps walking; and then it happens again; and again; always changing from old to young and back; and in that way, never changing.

My grandfather came into the den, where I was now sitting with my mom, totally stumped about where I fit into all this. My grandfather tried to coax my mom back to the table but she said, “No, I’m good right here.” He turned to me and asked if I’d like to see what he was writing. So we went into the basement and, on his computer, he pulled up his novel, the one he’d later send. My grandfather said that he was really fed up with novelists always writing such disappointing characters; novels were full of losers, and he couldn’t see why anyone would be interested in reading about such people. In contrast, he had written about a character who was not a loser, and whose life was not a disappointment.

I haven’t told you enough about the novel. Its protagonist is a man named Klaus who, just like my grandfather, is a German-American doctor and veteran. He is pursued by a number of women, Elizabeth included, whose “buns almost dance in anticipatory rhythm,” so excited are they to sleep with him. The conceit of the novel is that Klaus has written a book about his life to date, and his wife is reading it to the couple’s nineteen-year-old daughter. The family is vacationing at a ski chalet, and Klaus is off performing complicated surgery on a tourist who took a tumble, leaving behind the two women to sip hot chocolate and speak adoringly of him. The daughter, a virtuous virgin, is also awaiting the arrival of her fiancé. He is a German-born neurosurgeon. The plan is to marry him, go to Harvard and then become an international lawyer, a venture capitalist or a neuroscientist. She takes after her father.

My dad came down to the basement and said that it was time to go to the airport, because our flight home was just before midnight. It was maybe eight. He went back upstairs to put on his coat. My grandfather said he thought it seemed like we were running off a little earlier than was necessary. But he clicked out of the Word document in which he was writing his novel and said he was proud that I was a writer, like him, and then I left him alone with the pots, with the world he had made.

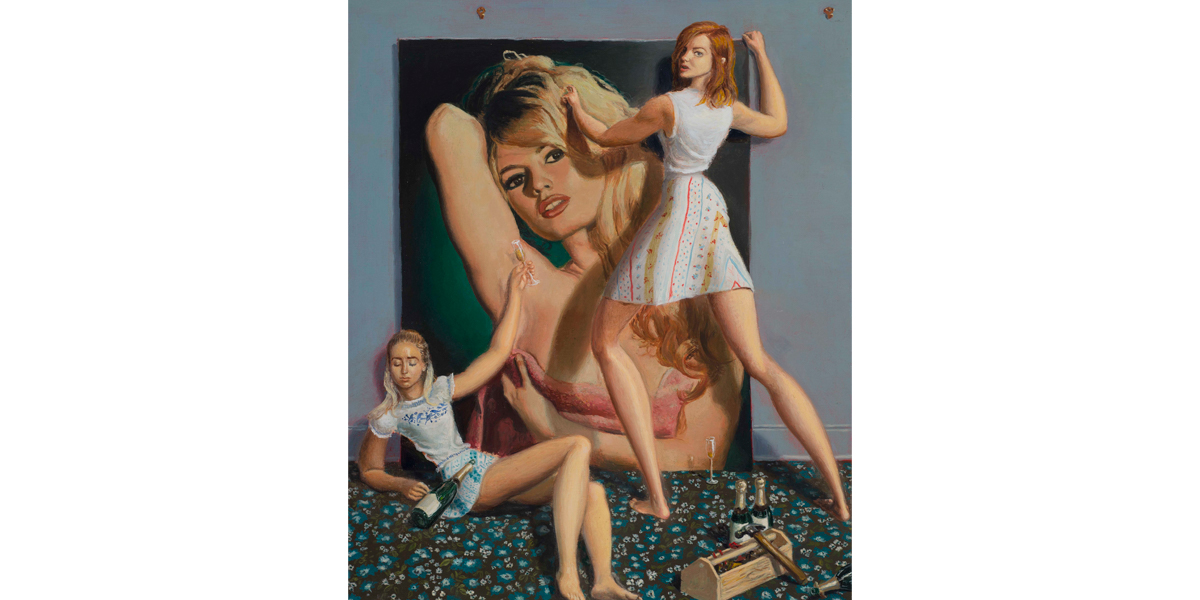

Art credit: Jansson Stegner. Study for “The Bibliophile II,” pen and ink wash on paper, 10 x 8 1/2 in, 2017; Bad Art Handling, oil on canvas, 24 x 20, 2017. All images courtesy of the artist and Nino Mier Gallery.

Listen to an audio version of this essay:

Last summer, my grandfather mailed me a copy of the erotic novel he had written in his basement, where he also has a ping-pong table and a collection of suspiciously acquired Mexican pots. In my grandfather’s erotic novel, one of the leading women is named Elizabeth, and she is chasing a uniquely brilliant doctor, a god among men. However, the odds of her bedding him are against her. This is because: “Elizabeth stripped naked and looked at herself in the full-length mirror. ‘Just look at me,’ she wailed. ‘Wrinkled. Flat-chested.’”

Elizabeth is undressing in the company of her “maid,” whose name is Maria. Elizabeth instructs Maria to likewise disrobe so she can “see how I stack up.” Maria is a little put out, but she complies so that Elizabeth can review Maria’s “boobs” as “nubile” and “great”; also, her hips are “just great hips.” The effect is so “great” that Elizabeth opines, “If I were a man, I’d be interested in fertilizing you.”

Alas, Elizabeth says, “in a tone of melancholy,” she does not expect that her own boobs and hips will please the brilliant doctor; in fact, she muses, “nothing but a body transplant will help me stack up sexually.” Maria tries to reassure her employer. Perhaps, she ventures, Elizabeth could try to win the doctor over slowly? Perhaps, by way of her personality?

“‘Maybe that can work for you, Maria,’ Elizabeth says. ‘You get sex regularly. Me, I haven’t had a cock in me in years.’” As foreseen, Elizabeth does not get this particular cock either; regrettably, the doctor senses in her “no sense of feminine sensuality to provoke a psychological response.”

My grandfather had signed the book’s “About the Author” page. There, he wrote: “To my granddaughter, Elizabeth.”

My grandfather is my mother’s father. The book arrived with the morning mail, and I read this particular passage aloud to my mom at lunch, and we laughed. We laughed while staring at each other as if asking, Is this the correct reaction? What do you feel? What are we supposed to think? “Elizabeth,” according to the text, is “based on a real person,” but we couldn’t decide who it was supposed to be. I was a candidate, for obvious reasons, but it could also be my mom, since, historically, her dad does not have nice things to say about the way she looks. It could also be a composite character, assembled from the bodies of many disappointing women. I did not know.

I kept reading, and by dinnertime I could tell my mom that other themes in the book include: the price of malpractice insurance, the worthlessness of religion, and the tragedy that is the existence of condoms (mercifully, the book’s most appealingly svelte women absolutely disdain them). There is also:

I once tried to write a college application essay about my grandfather, who is now nearly ninety. The essay was going to be about the alarming way he spoke to waitresses, which is fairly similar to how the doctor of his book addresses women, but my mom had said this was a bad idea: the admissions readers wouldn’t know what to make of him; he was way too weird. At the time, I had gone back upstairs to the family computer, reread the essay, and found that my mom was right. The essay was a mess; it was obvious that I didn’t know what to make of the man in it. Recently, I searched Amazon for the book he’d mailed to me, which was self-published. Its only review is a three-out-of-five-star rating, from someone who did not leave a comment, and who could not help me clarify what I should think.

●

My grandfather, like his protagonist, is a doctor. Specifically, he is a doctor of eyes. I know that, according to him, his parents were cruel and totally destitute. He met my grandmother in high school, and when she went to Gettysburg College, he went to work in a dynamite factory so that he could go to a nearby college, during which time he continued to date her. She was the prettiest girl at a very pretty college, the kind of place where the boys would steal the popular girls’ underwear and display the sweet little underthings outside. How embarrassing; how flattering. I have heard many times that the waistline of my grandmother’s wedding dress was 24 inches. My mom heard about this more than I did. The couple moved to New Mexico, and my grandfather stopped talking to his biological relatives. The two of them made a lot of money investing in whatever their stockbroker suggested, bought a house in the hills, kept the backyard pool at 83 degrees, became extremely preoccupied with immigration and taxation legislation, and acquired a great number of pots from a Santa Fe dealer who got them in who knows what way; the dealer is dead now.

My mom was born in 1964, and, after a dozen or so years of life, her dad began to ask if he could please buy her a nose job. My mom had her father’s nose, and it is forcefully aquiline. On a man, like my grandfather, it could be called majestic, like a wondrous mountain, the granddaddy of ski slopes, is sometimes called. My mom said she didn’t want one because she didn’t think there was anything wrong with her nose. She was a reclusive kid. She didn’t plan on becoming an actress or a model. For what did she need a made-for-television nose? At the time, my mom was a fourteen-year-old college student. Her world was divided between her parents’ house in rural New Mexico and university classrooms in which she did not quite speak the social language of her older peers. Yet, somehow, she had managed to perceive that there were worlds beyond her small one; spaces in which the size of her nose would be irrelevant to her happiness.

What did my grandfather want with a gorgeous daughter? My mom has always said that her dad was fixated on her marrying a neurosurgeon or a neuroscientist, so perhaps he thought that an alluring arrangement of facial bones would win her the correct husband. Still, why he imagined a specific profession for his daughter’s betrothed is another problem I can’t resolve. He also dreamed out loud to her that she would be an international lawyer. Also, that she would live in Paris. Actually, my mom took her biological nose to the East Coast, married a Catholic zoning lawyer and worked as a public defender. I texted my mom the other evening to ask why she thinks it mattered so much to her dad that she be what he wanted her to be, and she said, “I don’t know. You’d need a team of psychologists for that one.” Then she texted me a photo of a Greek lasagna she had baked.

One guess of mine is that my grandfather, an atheist who does not believe in afterlives, resolved that he had one life to live and that everything and everyone in it should therefore be as perfect as he can force them to be. Why not? I have a friend who is so pretty that she knows no matter how puzzling her behavior is at parties—for a while, she bit people indiscriminately—she will be rewarded with laughter, especially male laughter. But she would like to be even prettier. She told me on the phone, after an appointment that elongated her eyelashes, which followed an appointment that landscaped her eyebrows, that she had resolved to get a nose job. I said, Why? What’s wrong with your nose? And she said it was a little asymmetrical. I said, “But you’re already hot enough to get everything you ever need, and probably everything you want.” And she said, “What does that even mean, though?” What does it mean that she is hot “enough”? It seemed to her like, if the option is available to live as a very hot person, it is a form of deprivation to live any less hot of a life. I once read that people are most ornery about the income bracket just above theirs, which means that the extremely rich envy the extraordinarily rich.

Another friend of mine has a friend who is so pretty that restaurants pay for her to eat dinner inside them so that other patrons will perceive their dining experience as more rarefied. Before she met that friend, she told me, she didn’t even know that this next level of pretty privilege existed; when my friend found out, though, she didn’t particularly care. Because she seems phenomenally well-adjusted, I asked her how her mom talked to her about beauty, and she said, basically, her mom had banned all talk about prettiness or lack thereof. It was not a subject that she had grown up thinking much about. My mom didn’t talk about looks much either, yet somehow I spent a lot of my own teen years in front of H&M’s circular mirrors, assessing my nose from different angles while my mom waited outside the dressing-room curtain, inquiring as to when I was going to come to a conclusion; about the jeans, she meant.

The nose on my face is sort of like my mom’s nose, albeit softened by my dad’s nose, which is a bunny hill of a nose, gentle and unlikely to injure. The result, on me, is a perplexingly irregular creation. When I told my dad I hated it we were in the car, coming home from ballet class, and I was thirteen. He said, “Don’t you think that beauty standards are changing?” I cried and told him he was extremely wrong about that. Or at least, I explained, no one had conveyed this cultural change to the guys at school, or my ballet classmates, or, as far as I could discern, anyone outside this car; people seemed rather unaware that my nose was to be admired.

And I did want to be admired; specifically, I wanted for the things I said to be blessed with the worthiness that, so it seemed to me, is automatically conferred upon words that swoon out of lovely lips set beneath lovely noses. In middle-school art class we had to paint either a favorite quote or an original phrase as calligraphy. I decided to write my own phrase, so what I painted was: “Some see the blue jay, but never the sparrow.” This was before Facebook, so it was before it was possible to humiliate yourself by posting oblique and mopey song lyrics as your “status.” Instead, I aired my grievances in gigantic cursive, which was taped for all to see on the hallway’s white cinder block.

Two years later, I found myself doing a rendition of the “Cha-Cha Slide” dance one night behind an older guy from math class. It was a mutual friend’s birthday. We stepped to the right and stepped to the left and cha-cha-ed real smooth. This guy was very enthusiastic with his cha-cha. The mutual friend and I went to ballet school together, and we both had tiny, well-regulated hips, and we giggled at his rambunctious ones. We giggled harder when he asked if I’d like to dance. He was hot; I giggled, and declined, not because I didn’t want to dance, but because I was still embarrassed by attraction. The next morning in class, he tapped me on the shoulder and showed me the puckered cuts on his forearms. He said, “I did this because of you.” I was stunned. I was stunned with guilt, stunned by having hurt someone so blithely; but mostly I was stunned with joy. I was absolutely delighted that my judgment mattered to him. All along I thought I’d wanted to just be seen, but what I’d really wanted was to be seen doing the seeing. I was a hot girl. A mean one. But still—hot.

Wait, wait—was I actually hot? Another plot point in the encounter with the cha-cha dude is that, for the rest of the year, he conducted a war of math-class-based revenge: pulling my hair, writing on my neck in pen and tapping on my head with his pencil. It was the kind of indignity that I knew he would never commit on any actually hot women, who were by then intimidatingly ensconced in red cheerleading outfits. Years later, still wondering what species of bird I was, I looked up on Reddit how people know whether they are hot or not. One option, apparently, is to be so unimpeachably pretty that the world just hammers it into your head that you’re definitely attractive. “I’ve always been told that I was pretty, I modeled as a kid … I catch myself in the mirror and think, ‘damn girl, you beautiful,’” writes one alleged human being. Another is to post to the r/AmIHot subreddit and ask anonymous people if you have it going on (this, I guess is the virtual equivalent of undressing in front of “your maid” Maria). Still, people there will probably give you contradictory assessments. If you are clawing for a clarifying answer, and not just to be reassured that someone out there would like to sleep with you, this might be unsatisfying. So, one last solution, according to other people on Reddit, is this:

Is it possible to just decide that you’re hot? To declare yourself impervious to judgment? And just roll with that? I have a therapist now who loves to solve things. When I told her that I’m often very tired, she said I could avoid that if I stopped eating gluten and soy. When I told her that I still worry sometimes about whether I’m beautiful or not, she said, “Don’t worry. You are.” Well, all right. My boyfriend has a daughter, and she is two, and, ideally, he hopes that she will find herself beautiful. But he has also lived among humans for three decades, so he knows that life is full of mirrors that are at all times reflecting back to us images of ourselves that sometimes are not what we see, or what we want others to see. He also knows that what we see in those mirrors matters; that the images in them reach out and touch us. One thing he remembers from Catholic high school is that the hottest girl, the one whose name was spoken in reverence, and who was tiny and haloed in blond hair and sweetness, showed up at boy’s poker night, opened her purse, and produced a Bud Light. She popped the beer open. Nobody said anything. Nobody said anything, even though all the boys were terrified that the host’s parents would come into the living room, see the beer and yell. Nobody said anything, even though God Himself would be mad at them.

When I was young, and even now, with my twenties having just concluded, it was not particularly relevant to my quest to be cute that I knew contemporary beauty standards to be racist, ageist, classist, ableist, fatphobic and transphobic. Also, that they were, and are, misogynistic. That they are an invention of people trying to sell me creams, pills, underwear, magazines, etc. That they are totally antithetical to the shape that many healthy female bodies yearn to take. That they do not help the world. Nor does it really matter to me that a less-than-adorable childhood meant that, because people were not watching me, I could watch them; that I could learn in peace what people needed from me—which was, generally, to offer back to them confirmation of their own beauty. I would trade that education for a lifetime of prettiness. Because none of these facts change what has been true for me: that it is easier to be a hot girl opening an illicit Bud Light than it is to be a girl opening that beer without the protection of good looks. That those who are thin enough, and fine-featured enough, and blond enough, and clear-skinned enough, and tall enough but also short enough, and hot enough, wear the humiliations of life a little lighter than do the rest of us.

●

Before my grandfather wrote an erotic novel, he had self-published a coffee-table book on his large collection of pots. In it, he reported that he was the first to decipher their symbols, which, he said, primarily depict Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec god for whose pleasure humans once sacrificed beautiful creatures, like children.

The pots in my grandparents’ house were made about seven hundred years ago, by the people who once lived in Casas Grandes, a region in Mexico’s Chihuahua state. Most of them are white and round, with black-and-terra-cotta-colored geometrics; others are shaped like human figures, with protruding bellies, small feet and painted expressions that might just as well be surprise as longing or joy or devastation. Not long ago, I emailed the anthropologist Christine VanPool to ask if she could help me make sense of my grandfather’s book on the pots—if she could tell me what to think about at least one of his books—and she wrote back that yes, she would be delighted to talk about the book, though, she cautioned, some of his ideas “are challenging to evaluate.”

In 2003, a year after my grandfather self-published his book, VanPool finished her thesis at the University of New Mexico on the same pots. On the phone, she told me that a lot of his book’s conclusions about what the pots’ symbols meant were consistent with general truths applicable to cultures throughout the Southwest and Mesoamerica. For example, according to VanPool, the deity on many of the pots, whom my grandfather called Quetzalcoatl, is not exactly Quetzalcoatl, but probably is indeed a version of the Quetzalcoatl-like being that appears in variations across the region’s ancient cultures. Where my grandfather likely started going wrong, she explained, was when he called pots shaped like voluptuous women “goddesses”: like, the goddess of “female sexual power”; or the goddess that he said represented both “benevolence and debauchery.” They were probably not goddesses, she suggested, but women who had once been very much alive: “Each one is probably an actual female,” she said. “Who had a name. Who had a sense of person.”

The peoples of Casas Grandes are unusually inscrutable to us now. They were, and are, a borderland people. Back then, they were north of the Maya, south of the Apache. Now, they are in between the pyramids and pueblos, which attract much more scholarly attention. No one knows any more where the Casas Grandes peoples came from or what happened to them; we don’t know what language they spoke or what they called themselves. Anyway, VanPool said, she’d had lunch with my grandparents twenty years ago, in Albuquerque. It was a long and lovely conversation, she said, and, while she had promised to keep in touch, her first child was born shortly thereafter, and she had never followed through.

Oh actually, VanPool said, before hanging up, on second thought, maybe my grandfather was inadvertently right that the women figures were goddesses. Apache-speaking peoples, who lived contemporaneously with the Casas Grandes peoples in what is now the American Southwest, believed that when a girl transitioned into womanhood she became, briefly, the original woman who gave birth to mankind, by way of sleeping with the Sun and the Rain; the deity is sometimes called the Changing Woman. Perhaps, VanPool said, the peoples of Casas Grandes had believed the same. Perhaps their artists had captured the girls right at the moment of deification. VanPool has no idea, she said. She has no idea how these women grew up; no one does. And she has no idea how an artist might wish to represent them: Which women were worthy of committing to ceramic? At what moment in their lives?

Later, I googled the Apache rite, which is still practiced, and read a 1966 oral history of the Cibecue Apache, of Arizona, in which one father says that his daughter didn’t want to do the ceremony, both because “she was bashful” and because the ritual was old-fashioned and “her friends would tease her.” The girl didn’t believe that she had to embody the Changing Woman—which required dancing for several days straight in the August sun—in order to have whatever kind of womanhood she desired. The father says:

Recently I went for a walk with a friend, and I told them that I was thinking about how to protect a child from a world that might insist to her that she should look a very specific way; a look that might be painful to attain or maintain, or which could be unattainable or unsustainable. My friend had left behind the Mormon Church as a teen, and later, the gender assigned to them at birth. They pointed out that a kid might have no interest in being “hot” as I imagine “hot” to be, or “perfect” as my grandfather imagines “perfect” to be. This child might be repulsed by conventionality. Perhaps they will desire to stand out, and perhaps, if they get a big beak between their eyes, they will adore it. Maybe, the eyes that I sought on my own body will mean nothing to them; maybe, the judgment of a heteronormative-straight-cis-white-high-school-dude might land on them without impact. I was ashamed that these were not the first thoughts that arose in my own mind, when imagining what life would be like for my boyfriend’s child, or for a hypothetical child of my own. Of course the world in which they grow is growing too; of course it is growing in what it finds right and beautiful and worthwhile. Of course a child might want to look different than their parents wanted to look; of course they might not want to dance.

Yet I am still dancing. While I’d like to say that I now feel most beautiful dancing with my boyfriend’s daughter, wildly and fully and grandly, in hopes that she will learn to treat her body as her home, and as a home that is ostentatious with joy—this is not the truth in full. Because of course it still matters to me that when my boyfriend reaches out for me, to join me in my dance, the waist he touches is small.

●

For a little while, my mom had wanted me to have a relationship with my grandparents because that was the normal thing to do. She had met her father’s mother just once, in a hotel, and then never again. She knew almost nothing about her besides one anecdote, in which my grandfather saved up enough money to buy an ice cream, and then his mom took it from him and ate it herself. My own grandparents took me on vacation when I was about twelve. My grandpa called my grandma “Toots.” I asked if I could wear her lipstick, and she said no because the stick had grooved to the shape of her lips, after many, many years of applying it. She didn’t want to mess it up. At dinner, my grandfather said that if I grew up to be beautiful, I would attract a man who would take care of me, and who would take me to fine restaurants like this one. He was sure, he said, that my own dad hoped for the same salvation for me, even if he was too lefty to say so.

At night, my grandfather required that I let him put Neosporin on my acne, because, he said, it was better than all the creams on the market; doctors know best. I was embarrassed that he had seen my pimples, which I’d thought I was doing a good job of covering up with Maybelline, and so I sat next to him on the hotel bed and let him fix me. My mother had had the same issues with her skin, he said, but she had never let him help her. She was very stubborn that way, he said. Recently, I wondered out loud to my boyfriend, who gets along beautifully with everyone, if the best parents might be the people who just basically love all people, since parents universally have absolutely no idea what sort of person they are going to get.

When I was in high school, there was a months-long period during which my mom and her dad got along. He had gotten colon cancer and had become interested in God, and in God’s paradise, which meant that he had also become interested in living the earthly life that is prerequisite to spending the hereafter in the more beautiful of the two choices. When he went into remission, the two of them fell out again, and the most recent time I saw my grandparents was at a sort of truth-and-reconciliation-style dinner two years ago, at their house. It was New Year’s Eve, and my grandmother hobbled around the kitchen trying to put together a beef stroganoff. I held her hands, trying to help her get between the refrigerator and the stove, and my grandfather apologized to the table for her “gimpy” leg. In reply to inquiries, he assured the younger generations that she did not need a wheeler, because, as we could see, she gets around just fine. My grandmother said this was true and that her health was great, thanks to my grandfather, who, because he is a doctor (of the eyes), takes good care of her.

My grandfather uncorked French champagne (he only drinks French wines). He talked about his interests in child development and zoning laws, and he talked about his surprise that his wife, who had recently had a 23andMe test, did not turn out to be part-Portuguese, because she had such lovely olive skin. He remarked that my mom had done a nice job staying thin. He wanted to know if I had a boyfriend. I did; that boyfriend (not my current partner) was much older than me and had a nice office at a hedge fund, and my grandfather said this was wonderful, just like my figure. Eventually my mom got up and went into the den to scroll the New York Times website on her phone, because she was tired of hearing what her father had to say about anything.

There are limits to how much you can influence your children, and sometimes these limitations are tragic. It has made no difference to me, as an adult, that when I was little my mom didn’t wear makeup or fix her hair, that she didn’t give a damn about Pilates or what models ate for breakfast, and that she hoped, very much, that I would be like her; that I would not worry so much about what was on my face, which is so impermanent, no matter how lovely or not. I still grew up envious of the girls beside me in ballet class, whose parents bought them new noses for the stage; I still grew up wrapping a tape measure around my waist to make sure it never exceeded 24 inches. It also may not make any difference that my boyfriend’s daughter will grow up with a dad who hopes so badly that she will love her body, without maligning it or torturing it. She, like me, might discover that the tenderest, or the most fearless, or the most morally admirable princesses on television are also conventionally beautiful; she might also grow up to ask other people what she should think about her body. Or maybe, as with my mom and her parents, the limits to how much the adults in this child’s life can influence her, can pass on to her their own inheritances, will be a gift.

There are also limits to how much a person can forget their parents. Take, for example, a child who did not feel loved by his parents, and who grew into a man who did not know how to love a daughter. Take my grandfather. One fact about the Changing Woman is that she is said to endlessly walk the earth eastward, round and round, aging and aging, until she comes upon her young self again, merges with it and becomes young again; then she keeps walking; and then it happens again; and again; always changing from old to young and back; and in that way, never changing.

My grandfather came into the den, where I was now sitting with my mom, totally stumped about where I fit into all this. My grandfather tried to coax my mom back to the table but she said, “No, I’m good right here.” He turned to me and asked if I’d like to see what he was writing. So we went into the basement and, on his computer, he pulled up his novel, the one he’d later send. My grandfather said that he was really fed up with novelists always writing such disappointing characters; novels were full of losers, and he couldn’t see why anyone would be interested in reading about such people. In contrast, he had written about a character who was not a loser, and whose life was not a disappointment.

I haven’t told you enough about the novel. Its protagonist is a man named Klaus who, just like my grandfather, is a German-American doctor and veteran. He is pursued by a number of women, Elizabeth included, whose “buns almost dance in anticipatory rhythm,” so excited are they to sleep with him. The conceit of the novel is that Klaus has written a book about his life to date, and his wife is reading it to the couple’s nineteen-year-old daughter. The family is vacationing at a ski chalet, and Klaus is off performing complicated surgery on a tourist who took a tumble, leaving behind the two women to sip hot chocolate and speak adoringly of him. The daughter, a virtuous virgin, is also awaiting the arrival of her fiancé. He is a German-born neurosurgeon. The plan is to marry him, go to Harvard and then become an international lawyer, a venture capitalist or a neuroscientist. She takes after her father.

My dad came down to the basement and said that it was time to go to the airport, because our flight home was just before midnight. It was maybe eight. He went back upstairs to put on his coat. My grandfather said he thought it seemed like we were running off a little earlier than was necessary. But he clicked out of the Word document in which he was writing his novel and said he was proud that I was a writer, like him, and then I left him alone with the pots, with the world he had made.

Art credit: Jansson Stegner. Study for “The Bibliophile II,” pen and ink wash on paper, 10 x 8 1/2 in, 2017; Bad Art Handling, oil on canvas, 24 x 20, 2017. All images courtesy of the artist and Nino Mier Gallery.

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.