This is the first installment of our “Home Movies” column by Philippa Snow, about what we watch when no one’s watching.

Watched this week:

High Fidelity (2020) | High Fidelity (2000) | Guinevere (1999)

I have been inside for thirteen days, and in those thirteen days my only reliable contact with the outside world has been between 9:30 a.m. and 11:30 a.m. every morning, when a delivery driver drops off some new package for my partner. Always in that package is a 12” or a 7”, invariably from Canada or Hungary or outer space, or wherever happened to be offering rare progressive rock records in mint-minus condition shortly before everything on earth upended, turned to shit and became incrementally more terrifying with each government announcement. Because he had placed these orders before we were put on lockdown, they are bittersweet reminders of a time before assembling a crowd of sweating, necking people in a club to dance to music seemed like certain death. He copes by listening to them solo; as a freelance film critic, I cope by allowing my already-solitary day job to merge with my relaxation time, watching movie after movie and TV show after TV show with increasingly little regard for quality or genre. Maybe it is no surprise I split the difference between our respective passions by beginning with a show, and then a movie, about people who obsess over rare vinyl.

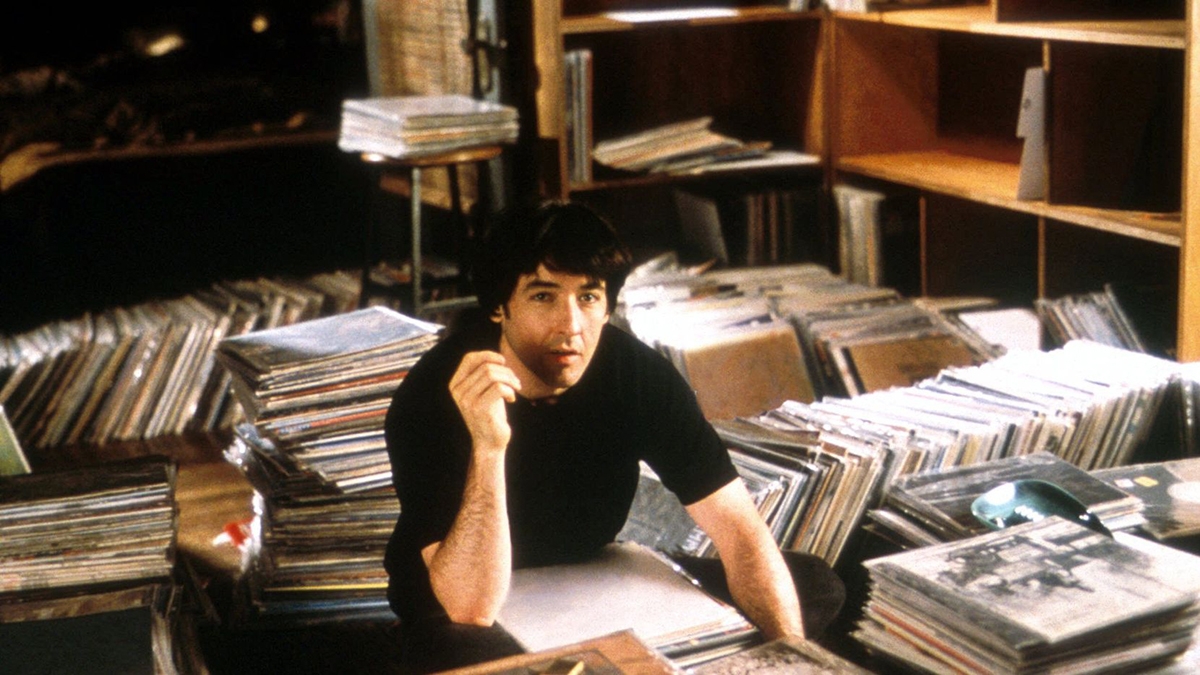

A fantasy-science-fiction series about Zoë Kravitz having been dumped by at least five people, Hulu’s High Fidelity is a ten-episode reworking of the 2000 classic1 with a neat trick up its sleeve: it recasts its misanthropic loser of a lead, Rob Gordon, as a bisexual black woman, but allows her to remain a selfish asshole. As before, Rob is the proprietor of Championship Vinyl; she has two offbeat employees, an eccentric, brassy show-off and a soft-spoken wallflower. Somewhat curiously, the store has relocated from Chicago to Crown Heights, making it less than plausible that it has barely any customers except on weekends. The High Fidelity reboot is nevertheless charming, tight and unchallenging, the equivalent of ten three-minute pop songs in a 4/4 rhythm. The whole thing is elevated by a witty, exquisitely modulated turn by Kravitz, who at times channels John Cusack’s grouchy and entitled Gen-X grumble in a manner that is borderline shamanic. Lines from the 2000 screenplay are not reinterpreted, but recreated slavishly, tic by unholy tic: they are Cusack’s lines exactly as he says them. The same effect, as if a woman were possessed by a bad-tempered man who smokes too many cigarettes, worked like gangbusters in Natasha Lyonne’s Russian Doll last year, making it unsurprising that Lyonne directs this show’s sixth episode, a meditation on the agony of drinking with your ex.

Those familiar with both versions will be able to extrapolate the reboot’s central thesis about the difference between women and men from a scene where Rob, rather than asking her former fiancée to confirm that he is not sleeping with the latest girl he’s seeing—as Cusack’s Rob does in the 2000 movie—asks him to confirm they’re not engaged, instead. I currently have all the time in the world to think about sexual politics, and none of the brainpower necessary to draw any interesting conclusions. The minutiae of our intimate relationships have in some ways never been less significant, making a rewatch of the original High Fidelity vaguely surreal: the O.G. Rob, still an obsessive but with a nastier streak, is pettier, even less interested in the bigger picture. (Take in High Fidelity in a pandemic, and I guarantee that you will ask who fucking cares, Rob? even more times that you might have done already.) Still, like Kravitz, Cusack has some mysterious quality that makes you eager to forgive him. It is possible that quality is “being a movie star,” a kind of ineffable that-ness which has almost nothing to do with good looks, or perfect teeth, or decent clothes. It might not strictly be charisma, since the person with the most charisma in the 2000 version of High Fidelity turns out to be Iben Hjejle, a measured and ice-cool Danish actress who has not appeared in many English-language films. When we use saints as the barometers for patience, we are likely to be picturing someone who looks like Hjejle, gentle and patrician with a white-blonde halo. She makes Rob seem twelve years old at his most erudite and interesting, and five when he is pouting.

Speaking, as we were, of twelve-year-olds: another film I watched with similar themes in that same week was Guinevere, whose portrait of the artist as a morally questionable man has a more feminine perspective. First released in 1999, Guinevere is the story of an aging alcoholic and his smart, naïve and too-young girlfriend, with a tone as sweet and sour as an ice-cold margarita. For an added note of realism, the older man does not look like Jude Law or Bradley Cooper, but like the character actor Stephen Rea, whose hangdog frown and rumpled face strike the right balance between loathsomeness and charm. He “enrolls” girls, all of whom he calls “Guinevere,” in a mentorship scheme that seems to involve about one-third photography instruction, one-third sex and one-third listening to other people’s “bohemian” chatter about life, the arts, philosophy, et cetera. That the film does not entirely side with Harper, the young, coltish ingénue, feels less uncomfortable than it does reasonable and pragmatic: Connie may be a habitual drunk and a seducer of young women, but his passion for photography at least helps to explain why nubile girls, trained by cinema and by literature to want a tortured artist, might line up to hear his lectures, then stay put for his advances.

Guinevere was written and directed by the late screenwriter Audrey Wells, whose only other directorial credit was the sunny, slight Under the Tuscan Sun in 2003. That film—about a woman in her thirties, played by Diane Lane, who relocates to Tuscany in order to begin a romance with herself—is similar to Guinevere only in its acknowledgement that good decisions sometimes arise from bad breakups with bad men. If the end of Stephen Frears’s High Fidelity is about Cusack’s Rob discovering that fantasies do not stand up to long-term, close-up scrutiny, Guinevere shows us the reverse: the dream girl realizing that the middle-aged male artiste doing the fantasizing leaves a lot to be desired himself. Both films, along with the new High Fidelity TV show, are about obsession, and about the degree to which obsessiveness is destructive when it is not tempered by humanity, or by a healthy regard for one’s fellow man. The flip side is that in both takes on High Fidelity, obsessiveness also begets community, the record shop becoming somewhere for like-minded freaks to congregate, the top-five lists a way for maladjusted nerds to come together and converse. That part at least is enviable, even if the rest is not. Obsessiveness is nothing without other people to obsess with. Already my boyfriend’s bored with all the records he’s received.

This is the first installment of our “Home Movies” column by Philippa Snow, about what we watch when no one’s watching.

Watched this week:

High Fidelity (2020) | High Fidelity (2000) | Guinevere (1999)

I have been inside for thirteen days, and in those thirteen days my only reliable contact with the outside world has been between 9:30 a.m. and 11:30 a.m. every morning, when a delivery driver drops off some new package for my partner. Always in that package is a 12” or a 7”, invariably from Canada or Hungary or outer space, or wherever happened to be offering rare progressive rock records in mint-minus condition shortly before everything on earth upended, turned to shit and became incrementally more terrifying with each government announcement. Because he had placed these orders before we were put on lockdown, they are bittersweet reminders of a time before assembling a crowd of sweating, necking people in a club to dance to music seemed like certain death. He copes by listening to them solo; as a freelance film critic, I cope by allowing my already-solitary day job to merge with my relaxation time, watching movie after movie and TV show after TV show with increasingly little regard for quality or genre. Maybe it is no surprise I split the difference between our respective passions by beginning with a show, and then a movie, about people who obsess over rare vinyl.

A fantasy-science-fiction series about Zoë Kravitz having been dumped by at least five people, Hulu’s High Fidelity is a ten-episode reworking of the 2000 classic1which is itself an adaptation of the 1995 Nick Hornby novel with a neat trick up its sleeve: it recasts its misanthropic loser of a lead, Rob Gordon, as a bisexual black woman, but allows her to remain a selfish asshole. As before, Rob is the proprietor of Championship Vinyl; she has two offbeat employees, an eccentric, brassy show-off and a soft-spoken wallflower. Somewhat curiously, the store has relocated from Chicago to Crown Heights, making it less than plausible that it has barely any customers except on weekends. The High Fidelity reboot is nevertheless charming, tight and unchallenging, the equivalent of ten three-minute pop songs in a 4/4 rhythm. The whole thing is elevated by a witty, exquisitely modulated turn by Kravitz, who at times channels John Cusack’s grouchy and entitled Gen-X grumble in a manner that is borderline shamanic. Lines from the 2000 screenplay are not reinterpreted, but recreated slavishly, tic by unholy tic: they are Cusack’s lines exactly as he says them. The same effect, as if a woman were possessed by a bad-tempered man who smokes too many cigarettes, worked like gangbusters in Natasha Lyonne’s Russian Doll last year, making it unsurprising that Lyonne directs this show’s sixth episode, a meditation on the agony of drinking with your ex.

Those familiar with both versions will be able to extrapolate the reboot’s central thesis about the difference between women and men from a scene where Rob, rather than asking her former fiancée to confirm that he is not sleeping with the latest girl he’s seeing—as Cusack’s Rob does in the 2000 movie—asks him to confirm they’re not engaged, instead. I currently have all the time in the world to think about sexual politics, and none of the brainpower necessary to draw any interesting conclusions. The minutiae of our intimate relationships have in some ways never been less significant, making a rewatch of the original High Fidelity vaguely surreal: the O.G. Rob, still an obsessive but with a nastier streak, is pettier, even less interested in the bigger picture. (Take in High Fidelity in a pandemic, and I guarantee that you will ask who fucking cares, Rob? even more times that you might have done already.) Still, like Kravitz, Cusack has some mysterious quality that makes you eager to forgive him. It is possible that quality is “being a movie star,” a kind of ineffable that-ness which has almost nothing to do with good looks, or perfect teeth, or decent clothes. It might not strictly be charisma, since the person with the most charisma in the 2000 version of High Fidelity turns out to be Iben Hjejle, a measured and ice-cool Danish actress who has not appeared in many English-language films. When we use saints as the barometers for patience, we are likely to be picturing someone who looks like Hjejle, gentle and patrician with a white-blonde halo. She makes Rob seem twelve years old at his most erudite and interesting, and five when he is pouting.

Speaking, as we were, of twelve-year-olds: another film I watched with similar themes in that same week was Guinevere, whose portrait of the artist as a morally questionable man has a more feminine perspective. First released in 1999, Guinevere is the story of an aging alcoholic and his smart, naïve and too-young girlfriend, with a tone as sweet and sour as an ice-cold margarita. For an added note of realism, the older man does not look like Jude Law or Bradley Cooper, but like the character actor Stephen Rea, whose hangdog frown and rumpled face strike the right balance between loathsomeness and charm. He “enrolls” girls, all of whom he calls “Guinevere,” in a mentorship scheme that seems to involve about one-third photography instruction, one-third sex and one-third listening to other people’s “bohemian” chatter about life, the arts, philosophy, et cetera. That the film does not entirely side with Harper, the young, coltish ingénue, feels less uncomfortable than it does reasonable and pragmatic: Connie may be a habitual drunk and a seducer of young women, but his passion for photography at least helps to explain why nubile girls, trained by cinema and by literature to want a tortured artist, might line up to hear his lectures, then stay put for his advances.

Guinevere was written and directed by the late screenwriter Audrey Wells, whose only other directorial credit was the sunny, slight Under the Tuscan Sun in 2003. That film—about a woman in her thirties, played by Diane Lane, who relocates to Tuscany in order to begin a romance with herself—is similar to Guinevere only in its acknowledgement that good decisions sometimes arise from bad breakups with bad men. If the end of Stephen Frears’s High Fidelity is about Cusack’s Rob discovering that fantasies do not stand up to long-term, close-up scrutiny, Guinevere shows us the reverse: the dream girl realizing that the middle-aged male artiste doing the fantasizing leaves a lot to be desired himself. Both films, along with the new High Fidelity TV show, are about obsession, and about the degree to which obsessiveness is destructive when it is not tempered by humanity, or by a healthy regard for one’s fellow man. The flip side is that in both takes on High Fidelity, obsessiveness also begets community, the record shop becoming somewhere for like-minded freaks to congregate, the top-five lists a way for maladjusted nerds to come together and converse. That part at least is enviable, even if the rest is not. Obsessiveness is nothing without other people to obsess with. Already my boyfriend’s bored with all the records he’s received.

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.