Finding myself accidentally in Berlin on November 9, I wandered through the city with a million other visitors mesmerized by a commemorative project called Lichtgrenze (“border of lights”), a fifteen-kilometer-long installation of illuminated helium balloons marking the footprint of the wall that had fallen 25 years ago that day.

While the notion of even figuratively “rebuilding” the Berlin Wall might have seemed unsettling, its luminous permeability delighted the crowds as a contrast to the Cold War barriers that it defiantly supplanted. The elaborate display lasted only three days, another vivid antithesis to the wall that divided the city for three decades.

It was a heartening coda to the week I had just spent deluged in Eastern Europe’s unfolding crisis. I was in Berlin on my way home from Cottbus, two hours southeast of the capital near the Polish border, which has hosted an annual Festival of Eastern European Cinema since 1991, the year of German reconciliation. Its purpose was to establish a cultural viaduct that would, through film, reconnect two halves of a continent that had been so starkly split apart.

As the region again faces turmoil, I hoped the films could help me make sense of the current political situation. I have considerable difficulty understanding what’s going on in Ukraine from the news and political commentary. Is it a bona fide “war”? Why is it happening? Does it stem from irredentism, revanchism, post-Soviet ultranationalism, Realpolitik, neo-Eurasianism?

So I went to the movies. Precisely because they didn’t profess to embody geopolitical analysis, I thought the films at the festival might provide valuable intelligence. I watched about twenty Russian and Ukrainian films, most of which had been in production as the conflict erupted. (It goes without saying that American audiences will find it difficult to see most of these films, but keep an eye out for them anyway: a few could turn up on Netflix, or at a film festival closer to home.) My plan to read the world through film seemed all the more promising when I learned that the festival’s main theater, a beautiful Art Nouveau movie house, is called the Weltspiegel, which literally translates as “world mirror.” Recalling Prince Hamlet’s contention that drama’s purpose is “to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature,” the Weltspiegel reinforced my expectation that these films might offer an edifying reflection on the societies that produced them.

The Weltspiegel theater in Cottbus, Germany, built in 1911 as a cinema and still functioning as one today

Unsurprisingly, the Ukrainian films resounded with loss, frustration, angst, despair, resentment and resignation. Most simply portrayed communities that were suffering unremittingly. Occasional scenes broached faint hopes for a resurgent Ukrainian glory, but these were mostly quixotic. And there was a good deal of extravagant nostalgia, meant to contrast with the stunted and unlovely present. A film like Ivan the Powerful—based on the true story of a Carpathian circus performer who toured Europe in the 1930s, billed as the strongest man in the world— obviously expresses a compelling fantasy for a country that is now so weak.

But the Russian films, too, were filled with frustration: troubled and violent, they presented broken families and dysfunctional personal relationships. The characters and the milieus were cynical and corrupt; the worldview pervasively confused (as it was, too, in the Ukrainian films), suggesting a frayed sense of social stability and cohesion. Bullies, oligarchs and tyrants were ubiquitous, and uniformly portrayed as antagonistic; all the Russian filmmakers seemed starkly opposed to the ethos of Putinism.

A proverbial Martian, wandering into this festival, might not be able to tell which country was oppressing the other. The narratives seemed to indicate a codependent relationship, as if both countries were clinging to one another in a darkly complex muddle. Russian and Ukrainian cinematography tends to feature a common style: exaggerated melodrama that hits viewers on the head and declaims key points a few times for emphasis, evoking Sergei Eisenstein’s Expressionist tradition from nearly a century ago. Like Irish Unionists and Nationalists, or Indians and Pakistanis, the combatants may be fundamentally more similar than different.

Balazher: The Corrections of Reality, an unassuming short Ukrainian documentary, shows the crumbling infrastructure that mirrors a crumbling psyche. It’s about a public bus—a rusted junker jury-rigged together that seems unlikely to make it to the next stop without stalling—and the people who are waiting bitterly for it to come (or not: a Godot-flavored existentialism infuses contemporary Ukrainian cinema). Thirty-one year old filmmaker Lesia Kordonets interviews the would-be passengers standing in the snow at the bus stop, where they share their views of their world:

“We want to achieve something, but nothing gets achieved.”

“We’re striding, but not moving forward.”

“Everybody’s waiting. One waits for the bus, another for his pension…”

“Or for a better life.”

“And you only get older.”

“The bus probably won’t come, will it?”

“Were things better during Soviet rule?” Kordonets asks. “No big difference, but at least then the street lights stayed on.”

A forlorn bus stop in a forlorn Ukrainian border town, from Balazher: The Corrections of Reality.

The bus driver has plied his route for 41 years, from Chopivka to Janosi to Balazher to Mage Begany to Kis Begany—all border villages. “I guess this line is the border of borders in Europe,” he says. “It used to be the USSR. And now this line is the outermost border of the European Union against us, the Ukraine. This border was difficult to cross back then, but it still is today. I think Europe is still divided—now the Iron Curtain is being installed from the other side, the E.U.”

The film’s larger implications are pretty obvious, but the symbolism is still compelling: everything is on its last legs, patched tenuously together. The bus is in the repair shop more than on the road. “Don’t ask how I’ll fix this,” the hapless mechanic says, “it’s tricky. There are no spare parts. They are expensive.”

Two films shown at the festival were shot in Kiev’s central square during the uprising of November 2013 through February 2014. The first, Once Upon a Time in Ukraine, tells a visually intense but ploddingly histrionic story about a woman raped in Crimea who flees to Kiev, where she sees the policemen who assaulted her in the Maidan crowds as the protests unfold.

A still from Once Upon a Time in Ukraine.

Stunningly brutal images of the Maidan massacre couldn’t quite carry this heavy-handed story. Still, the attempted parallelism of personal and national horror is an interesting failure for director Igor Parfenov. Parfenov, who also stars in the film, acknowledged in his post-screening discussion that the script was thrown together quickly so he could integrate the actual riots.

A more successful depiction of the Maidan protests is Almanac #Babylon ’13: Cinema of Civil Society, a hodge-podge of stories compiled on a shoestring budget by a collective of guerrilla documentarians who call themselves “Art Collective #Babylon ’13.” Like Parfenov, the documentarians rushed to the front lines as the battle began, but they didn’t impose a contrived narrative on it. Rather, aided by the kaleidoscopic documentary lens, they let the people who were there reveal the story in its own dramatic reality.

We hear in personal testimonies, rather than journalistic or militaristic discourse, about the assaults on the ragtag grassroots movement of citizen protestors. “They were just shooting people who couldn’t shoot back,” one participant says. “I don’t understand. We”—that is, both the protestors and the armed forces bolstering Ukraine’s pro-Russian Yanukovych government—“are the same people who live in the same country, and some shoot others who can’t shoot back.”

●

The Russian films were about social despair. Perhaps Russian narratives always have been: in fact, one of the films, Dubrovsky, was a faithful iteration of Alexander Pushkin’s 1832 novella about the infectious greed of rich people who feel entitled and compelled to get richer, and all the little people who are devoured in the process. Cottbus audiences left that film remarking (in several different languages) that nothing much seems to have changed.

There were two brave and profoundly depressing Russian gay films. Children 404 is a documentary about an improbable activist movement to support the country’s gay teens, who suffer the rampant homophobia exemplified and encouraged by Russia’s recent anti-gay legislation (forbidding “homosexual propaganda”). Filmmakers Askold Kurov and Pavel Loparev are participating in social media outreach beyond the film, continuing their efforts to help these kids sustain a positive sense of identity against the silencing and social stigma they face. And Janthan Taïeb’s feature film Stand, a Russian-Ukrainian coproduction, tells of a gay Russian couple who witness a gay-bashing murder and try, risking great peril, to attain justice for the victim.

In Children 404, several teens (many with their faces hidden) describe the pressures they face to remain invisible, balanced against the near-impossibility of keeping their sexuality completely suppressed. Virulent homophobia is rampant in schools, exemplified by classmates who say things to them like, “If Hitler was in power you’d have been shot a long time ago.” School counselors blame the gay students themselves for inciting homophobia: “What can you expect?” And families, too, offer little support: one mother tells her son he’s gay because he’s overweight and unattractive.

It was impressive to see filmmakers broaching the topic in the face of such extreme political and social prejudice, though these films make it seem as if Russia’s bigotry is almost insurmountable: I would said absolutely impregnable except for the fact that these films have been produced and distributed. Still, both Children 404 and Stand convey an omnipresent threat, foregrounding the constant risks that endanger all gay Russians. The mere act of coming out, or even just being perceived as gay, may trigger accusations of criminal “activism.”

Fool depicts the kind of widespread civic corruption that the Russian masses (and the Soviet masses before them) have long suffered and always resented. Dimy, a plumber called in the middle of the night to fix a burst pipe in a hulking Soviet-era tenement, realizes that the entire building, with its 800 residents, is in imminent danger of collapse: large cracks in the walls show that the foundation has shifted and the apartment building has tilted dangerously. When he informs his bosses, the city leaders, about the danger, they have no concerns other than covering their own asses, and the story follows a series of bureaucratic stalls and cover-ups that would be darkly comic if they weren’t so tragically inhumane. Realizing that the officials are determined to ignore the danger, Dimy himself finally decides to evacuate the tenants in the middle of the night, but his wife is even more cynical than the officials. Knowing he is in danger for whistleblowing, she demands that he leave the city with her and their son immediately. He cannot convince her that the 800 lives matter; what are they to us, she asks? Like the bureaucrats, she believes that the Russian masses will always suffer, and anyone who tries to buck the system is a fool.

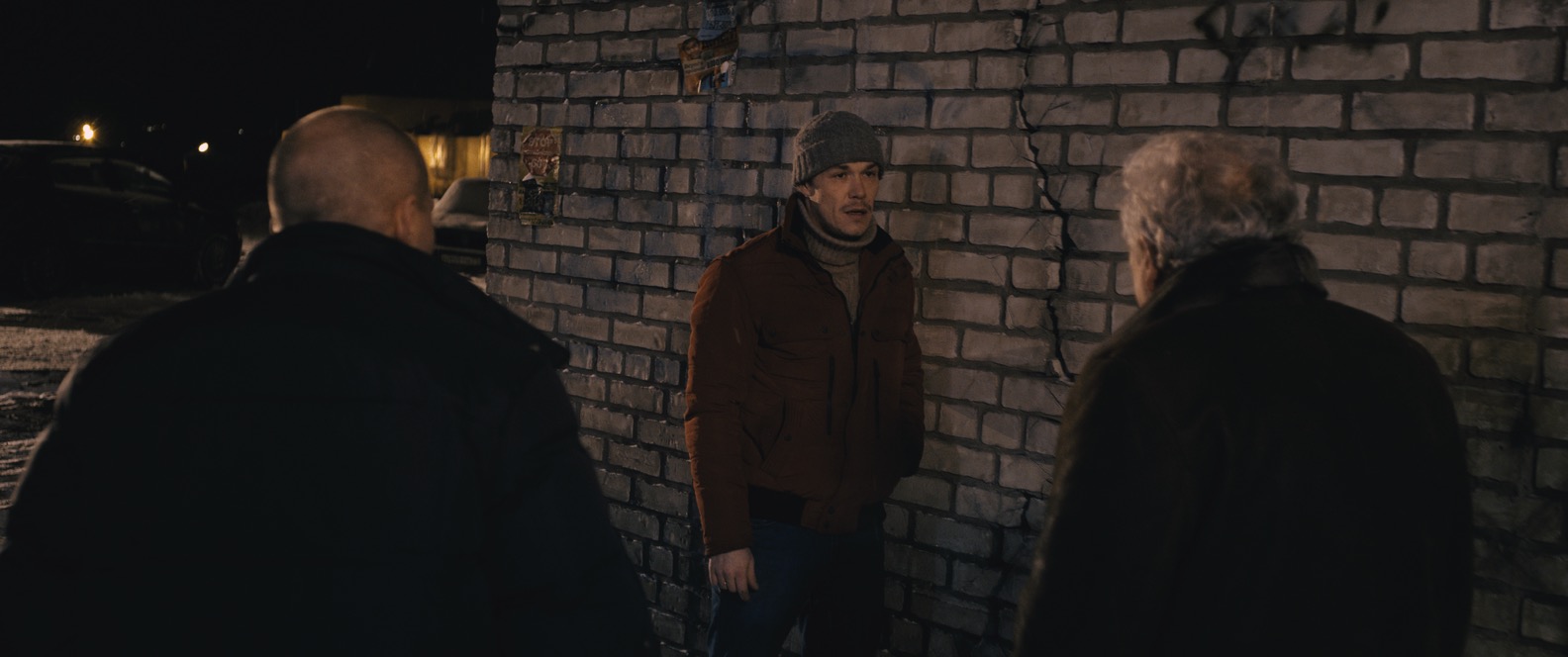

Dimy, a repairman in Fool, tries to explain to his supervisors that this crack in the side of an apartment building means that it is liable to collapse at any moment.

Director Yuri Bykov affirms that Dimy is indeed a fool: the residents he rescues congregate outside for a few minutes and then turn on him. Certain that he is conning them in some way (as they are used to being conned), they beat him and leave him inert on the ground outside the building in the final shot. The system is indelibly corrupt, Bykov moralizes; don’t be like Dimy—look out for yourself.

Corrections Class (awarded the festival’s prize for best film) is another depiction of tragic gaps in the Russian social fabric. The film tells the story of a dozen teens who, though they could have functioned perfectly well in a regular class, are shunted into a special ed. track where the school’s other students persecute them and the teachers treat them like morons. They eventually internalize the eugenicist prejudices that surround them and fulfill the predictions of their failure. When I asked director Ivan Tverdovsky if his film had an allegorical message about how society treats those who are troubled and disempowered, he responded dismissively: “It’s not about politics. I’m not interested in politics.” Responding to another question a few minutes later he explained, “What I show in this film is a universal story that happens throughout society: people mistreating other people and masking the problems.” The moderator caught him up on this, and referring back to my question, said, “So it is a political allegory,” to which he rolled his eyes and said nothing.

To my eyes, the films at the festival offered pretty much what I had thought I might see in terms of an etiology, and a keen cultural critique, of what was wrong in this region. Russian films expose their bullies, despots, and homophobes as hateful, unchecked powermongers; Ukrainian cinema movingly depicts the chaos and upheaval that testify to their people’s plight as victims. A desperate milieu of anomic degradation creates a moral vacuum, leading to a situation where one country blithely disregards international law and confiscates pieces of another country; where yobs shoot randomly at passenger planes flying overhead. Social obligations are meaningless, the social contract is broken.

Yet many of the filmmakers and film industry people I spoke with contested suggestions that these films were even about the political situation, much less that they would bring reform. When I asked them about local responses to their films—wondering if they upheld the Brechtian ideal whereby audiences, after the play, are expected to run out of the theater and riot in the streets—they were cautious and, like Tverdovsky, reluctant to acknowledge political subtexts.

“Audiences are uncertain and nervous about what the movies should do,” said Julia Sinkyevich, director of the Odessa Film Festival. Ukrainian filmmakers “obviously have a strong sense of trying to deal with the issues about the unrest, but people are resistant.” Marcel Maiga, who curated the Cottbus Festival’s Russian program, told me, “The films aren’t that subversive. They’re just about people’s individual problems. Audiences go to see them, and may relate to them because they live in the same society and have the same problems. But then, after the movie, they go back to their lives. Few are probably really inspired to change things.”

Russian director Nana Djordjadze, who worked in Odessa during the hostilities with a crew made up of many different nationalities, also demurred at my proposition that these films might help motivate resistance to nationalistic demagoguery. “During the shooting”—of the film, she meant— “we talked with each other about politics, about this crazy war. Nobody likes it; nobody wants to be in a war. But as we are working, we are all together. We must love our enemies, and cross this border of hate.”

Against my assumption that these films embodied a potent moral and political vision, the majority of festival-goers seemed to regard them as fringe artifacts, reminding me that audiences in their countries, like audiences everywhere, go to the movies seeking escapism or distraction rather than detailed analyses of their struggles and suffering. (Russia’s top three grossing 2014 films are Transformers, Maleficent, and Guardians of the Galaxy.) Maiga wondered if “maybe the films seemed especially political to you because you’re from outside this society. Most people here think, ‘it’s just art,’” he said. “The corruption, and bullying, and other problems seem striking, and politically driven; but to Russian audiences, this is just the way things are. These are all individual stories—about people who happen to live in Russia in a certain time and in a certain set of circumstances.”

So while I believe that these films all richly invite interpretation through the lens of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, I also came to appreciate that this perspective was, distinctly, my outsider’s response. Eastern European festival-goers seemed to find these films more affirming than depressing: cathartic experiences, I imagine, that depicted and validated the challenges of their everyday difficulties. The mere existence of such a broad film schedule speaks to an artistic endurance that filmmakers and audiences both celebrated. About 30 percent of Ukrainian movie theaters have “closed or disappeared” in the last year of hostilities, Sinkyevich told me. Her Odessa Festival survived this year, barely, thanks to the kindness of others: she received extensive financial and organizational support from other Western European film festivals.

While this year’s crop of films made it through production and onto programs at Odessa, Cottbus, and elsewhere, Sinkyevich thinks next year’s harvest will be more constricted. Amid the current upheaval, filmmaking may be an unaffordable luxury. Russians, waiting for the other shoe to drop after Western sanctions, expressed similar fears about their film industry in the face of expected economic contraction. Part of the excitement at this year’s Russian and Ukrainian programs was, sadly, that this might be their last hurrah, at least for a while.

●

The Cottbus Festival does a laudable job of facilitating vital European dialogues. It’s particularly appropriate for Germans to be hosting such a program, because there, in the former DDR, one is supremely inclined to hope that twentieth-century Europe’s tragedies may have been resolved; people have recovered; and, informed by the horrifying lessons of the past, people are moving forward with enlightened optimism. Stumbling into Berlin’s “Mauerfall 25” celebrations was for me such a perfect pièce de résistance.

But even as the crowds basked in the lights of freedom at Brandenburg gate there was a sour note, tempering our complacency about having eradicated totalitarianism and vanquished a stalemate of geopolitical belligerence. Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader and a guest of honor at Berlin’s ceremonies, warned that current tensions between Russia and the West have moved the world to “the brink of a new Cold War.” It was just a quick sound bite, overshadowed by the festive outpouring, but still it was an ominous warning.

Again and again—after the Great War, after World War II, after the Holocaust, after the Cold War, after Sarajevo and Srebrenica and South Ossetia and Kosovo—people wanted to believe that the cycles of conflict were over, and that the borders and treaties were finally fixed in ways that would allow Europeans to move forward peacefully. Today’s newsfeed indicates otherwise. Cottbus’s films, documents from the front lines of a dangerously volatile eruption, show with piercing pathos the kind of simple, precise peril that W. H. Auden identified in his 1938 sonnet sequence “In Time of War”: “maps can really point to places / Where life is evil now.”

Finding myself accidentally in Berlin on November 9, I wandered through the city with a million other visitors mesmerized by a commemorative project called Lichtgrenze (“border of lights”), a fifteen-kilometer-long installation of illuminated helium balloons marking the footprint of the wall that had fallen 25 years ago that day.

While the notion of even figuratively “rebuilding” the Berlin Wall might have seemed unsettling, its luminous permeability delighted the crowds as a contrast to the Cold War barriers that it defiantly supplanted. The elaborate display lasted only three days, another vivid antithesis to the wall that divided the city for three decades.

It was a heartening coda to the week I had just spent deluged in Eastern Europe’s unfolding crisis. I was in Berlin on my way home from Cottbus, two hours southeast of the capital near the Polish border, which has hosted an annual Festival of Eastern European Cinema since 1991, the year of German reconciliation. Its purpose was to establish a cultural viaduct that would, through film, reconnect two halves of a continent that had been so starkly split apart.

As the region again faces turmoil, I hoped the films could help me make sense of the current political situation. I have considerable difficulty understanding what’s going on in Ukraine from the news and political commentary. Is it a bona fide “war”? Why is it happening? Does it stem from irredentism, revanchism, post-Soviet ultranationalism, Realpolitik, neo-Eurasianism?

So I went to the movies. Precisely because they didn’t profess to embody geopolitical analysis, I thought the films at the festival might provide valuable intelligence. I watched about twenty Russian and Ukrainian films, most of which had been in production as the conflict erupted. (It goes without saying that American audiences will find it difficult to see most of these films, but keep an eye out for them anyway: a few could turn up on Netflix, or at a film festival closer to home.) My plan to read the world through film seemed all the more promising when I learned that the festival’s main theater, a beautiful Art Nouveau movie house, is called the Weltspiegel, which literally translates as “world mirror.” Recalling Prince Hamlet’s contention that drama’s purpose is “to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature,” the Weltspiegel reinforced my expectation that these films might offer an edifying reflection on the societies that produced them.

The Weltspiegel theater in Cottbus, Germany, built in 1911 as a cinema and still functioning as one today

Unsurprisingly, the Ukrainian films resounded with loss, frustration, angst, despair, resentment and resignation. Most simply portrayed communities that were suffering unremittingly. Occasional scenes broached faint hopes for a resurgent Ukrainian glory, but these were mostly quixotic. And there was a good deal of extravagant nostalgia, meant to contrast with the stunted and unlovely present. A film like Ivan the Powerful—based on the true story of a Carpathian circus performer who toured Europe in the 1930s, billed as the strongest man in the world— obviously expresses a compelling fantasy for a country that is now so weak.

But the Russian films, too, were filled with frustration: troubled and violent, they presented broken families and dysfunctional personal relationships. The characters and the milieus were cynical and corrupt; the worldview pervasively confused (as it was, too, in the Ukrainian films), suggesting a frayed sense of social stability and cohesion. Bullies, oligarchs and tyrants were ubiquitous, and uniformly portrayed as antagonistic; all the Russian filmmakers seemed starkly opposed to the ethos of Putinism.

A proverbial Martian, wandering into this festival, might not be able to tell which country was oppressing the other. The narratives seemed to indicate a codependent relationship, as if both countries were clinging to one another in a darkly complex muddle. Russian and Ukrainian cinematography tends to feature a common style: exaggerated melodrama that hits viewers on the head and declaims key points a few times for emphasis, evoking Sergei Eisenstein’s Expressionist tradition from nearly a century ago. Like Irish Unionists and Nationalists, or Indians and Pakistanis, the combatants may be fundamentally more similar than different.

Balazher: The Corrections of Reality, an unassuming short Ukrainian documentary, shows the crumbling infrastructure that mirrors a crumbling psyche. It’s about a public bus—a rusted junker jury-rigged together that seems unlikely to make it to the next stop without stalling—and the people who are waiting bitterly for it to come (or not: a Godot-flavored existentialism infuses contemporary Ukrainian cinema). Thirty-one year old filmmaker Lesia Kordonets interviews the would-be passengers standing in the snow at the bus stop, where they share their views of their world:

“Were things better during Soviet rule?” Kordonets asks. “No big difference, but at least then the street lights stayed on.”

A forlorn bus stop in a forlorn Ukrainian border town, from Balazher: The Corrections of Reality.

The bus driver has plied his route for 41 years, from Chopivka to Janosi to Balazher to Mage Begany to Kis Begany—all border villages. “I guess this line is the border of borders in Europe,” he says. “It used to be the USSR. And now this line is the outermost border of the European Union against us, the Ukraine. This border was difficult to cross back then, but it still is today. I think Europe is still divided—now the Iron Curtain is being installed from the other side, the E.U.”

The film’s larger implications are pretty obvious, but the symbolism is still compelling: everything is on its last legs, patched tenuously together. The bus is in the repair shop more than on the road. “Don’t ask how I’ll fix this,” the hapless mechanic says, “it’s tricky. There are no spare parts. They are expensive.”

Two films shown at the festival were shot in Kiev’s central square during the uprising of November 2013 through February 2014. The first, Once Upon a Time in Ukraine, tells a visually intense but ploddingly histrionic story about a woman raped in Crimea who flees to Kiev, where she sees the policemen who assaulted her in the Maidan crowds as the protests unfold.

A still from Once Upon a Time in Ukraine.

Stunningly brutal images of the Maidan massacre couldn’t quite carry this heavy-handed story. Still, the attempted parallelism of personal and national horror is an interesting failure for director Igor Parfenov. Parfenov, who also stars in the film, acknowledged in his post-screening discussion that the script was thrown together quickly so he could integrate the actual riots.

A more successful depiction of the Maidan protests is Almanac #Babylon ’13: Cinema of Civil Society, a hodge-podge of stories compiled on a shoestring budget by a collective of guerrilla documentarians who call themselves “Art Collective #Babylon ’13.” Like Parfenov, the documentarians rushed to the front lines as the battle began, but they didn’t impose a contrived narrative on it. Rather, aided by the kaleidoscopic documentary lens, they let the people who were there reveal the story in its own dramatic reality.

We hear in personal testimonies, rather than journalistic or militaristic discourse, about the assaults on the ragtag grassroots movement of citizen protestors. “They were just shooting people who couldn’t shoot back,” one participant says. “I don’t understand. We”—that is, both the protestors and the armed forces bolstering Ukraine’s pro-Russian Yanukovych government—“are the same people who live in the same country, and some shoot others who can’t shoot back.”

●

The Russian films were about social despair. Perhaps Russian narratives always have been: in fact, one of the films, Dubrovsky, was a faithful iteration of Alexander Pushkin’s 1832 novella about the infectious greed of rich people who feel entitled and compelled to get richer, and all the little people who are devoured in the process. Cottbus audiences left that film remarking (in several different languages) that nothing much seems to have changed.

There were two brave and profoundly depressing Russian gay films. Children 404 is a documentary about an improbable activist movement to support the country’s gay teens, who suffer the rampant homophobia exemplified and encouraged by Russia’s recent anti-gay legislation (forbidding “homosexual propaganda”). Filmmakers Askold Kurov and Pavel Loparev are participating in social media outreach beyond the film, continuing their efforts to help these kids sustain a positive sense of identity against the silencing and social stigma they face. And Janthan Taïeb’s feature film Stand, a Russian-Ukrainian coproduction, tells of a gay Russian couple who witness a gay-bashing murder and try, risking great peril, to attain justice for the victim.

In Children 404, several teens (many with their faces hidden) describe the pressures they face to remain invisible, balanced against the near-impossibility of keeping their sexuality completely suppressed. Virulent homophobia is rampant in schools, exemplified by classmates who say things to them like, “If Hitler was in power you’d have been shot a long time ago.” School counselors blame the gay students themselves for inciting homophobia: “What can you expect?” And families, too, offer little support: one mother tells her son he’s gay because he’s overweight and unattractive.

It was impressive to see filmmakers broaching the topic in the face of such extreme political and social prejudice, though these films make it seem as if Russia’s bigotry is almost insurmountable: I would said absolutely impregnable except for the fact that these films have been produced and distributed. Still, both Children 404 and Stand convey an omnipresent threat, foregrounding the constant risks that endanger all gay Russians. The mere act of coming out, or even just being perceived as gay, may trigger accusations of criminal “activism.”

Fool depicts the kind of widespread civic corruption that the Russian masses (and the Soviet masses before them) have long suffered and always resented. Dimy, a plumber called in the middle of the night to fix a burst pipe in a hulking Soviet-era tenement, realizes that the entire building, with its 800 residents, is in imminent danger of collapse: large cracks in the walls show that the foundation has shifted and the apartment building has tilted dangerously. When he informs his bosses, the city leaders, about the danger, they have no concerns other than covering their own asses, and the story follows a series of bureaucratic stalls and cover-ups that would be darkly comic if they weren’t so tragically inhumane. Realizing that the officials are determined to ignore the danger, Dimy himself finally decides to evacuate the tenants in the middle of the night, but his wife is even more cynical than the officials. Knowing he is in danger for whistleblowing, she demands that he leave the city with her and their son immediately. He cannot convince her that the 800 lives matter; what are they to us, she asks? Like the bureaucrats, she believes that the Russian masses will always suffer, and anyone who tries to buck the system is a fool.

Dimy, a repairman in Fool, tries to explain to his supervisors that this crack in the side of an apartment building means that it is liable to collapse at any moment.

Director Yuri Bykov affirms that Dimy is indeed a fool: the residents he rescues congregate outside for a few minutes and then turn on him. Certain that he is conning them in some way (as they are used to being conned), they beat him and leave him inert on the ground outside the building in the final shot. The system is indelibly corrupt, Bykov moralizes; don’t be like Dimy—look out for yourself.

Corrections Class (awarded the festival’s prize for best film) is another depiction of tragic gaps in the Russian social fabric. The film tells the story of a dozen teens who, though they could have functioned perfectly well in a regular class, are shunted into a special ed. track where the school’s other students persecute them and the teachers treat them like morons. They eventually internalize the eugenicist prejudices that surround them and fulfill the predictions of their failure. When I asked director Ivan Tverdovsky if his film had an allegorical message about how society treats those who are troubled and disempowered, he responded dismissively: “It’s not about politics. I’m not interested in politics.” Responding to another question a few minutes later he explained, “What I show in this film is a universal story that happens throughout society: people mistreating other people and masking the problems.” The moderator caught him up on this, and referring back to my question, said, “So it is a political allegory,” to which he rolled his eyes and said nothing.

To my eyes, the films at the festival offered pretty much what I had thought I might see in terms of an etiology, and a keen cultural critique, of what was wrong in this region. Russian films expose their bullies, despots, and homophobes as hateful, unchecked powermongers; Ukrainian cinema movingly depicts the chaos and upheaval that testify to their people’s plight as victims. A desperate milieu of anomic degradation creates a moral vacuum, leading to a situation where one country blithely disregards international law and confiscates pieces of another country; where yobs shoot randomly at passenger planes flying overhead. Social obligations are meaningless, the social contract is broken.

Yet many of the filmmakers and film industry people I spoke with contested suggestions that these films were even about the political situation, much less that they would bring reform. When I asked them about local responses to their films—wondering if they upheld the Brechtian ideal whereby audiences, after the play, are expected to run out of the theater and riot in the streets—they were cautious and, like Tverdovsky, reluctant to acknowledge political subtexts.

“Audiences are uncertain and nervous about what the movies should do,” said Julia Sinkyevich, director of the Odessa Film Festival. Ukrainian filmmakers “obviously have a strong sense of trying to deal with the issues about the unrest, but people are resistant.” Marcel Maiga, who curated the Cottbus Festival’s Russian program, told me, “The films aren’t that subversive. They’re just about people’s individual problems. Audiences go to see them, and may relate to them because they live in the same society and have the same problems. But then, after the movie, they go back to their lives. Few are probably really inspired to change things.”

Russian director Nana Djordjadze, who worked in Odessa during the hostilities with a crew made up of many different nationalities, also demurred at my proposition that these films might help motivate resistance to nationalistic demagoguery. “During the shooting”—of the film, she meant— “we talked with each other about politics, about this crazy war. Nobody likes it; nobody wants to be in a war. But as we are working, we are all together. We must love our enemies, and cross this border of hate.”

Against my assumption that these films embodied a potent moral and political vision, the majority of festival-goers seemed to regard them as fringe artifacts, reminding me that audiences in their countries, like audiences everywhere, go to the movies seeking escapism or distraction rather than detailed analyses of their struggles and suffering. (Russia’s top three grossing 2014 films are Transformers, Maleficent, and Guardians of the Galaxy.) Maiga wondered if “maybe the films seemed especially political to you because you’re from outside this society. Most people here think, ‘it’s just art,’” he said. “The corruption, and bullying, and other problems seem striking, and politically driven; but to Russian audiences, this is just the way things are. These are all individual stories—about people who happen to live in Russia in a certain time and in a certain set of circumstances.”

So while I believe that these films all richly invite interpretation through the lens of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, I also came to appreciate that this perspective was, distinctly, my outsider’s response. Eastern European festival-goers seemed to find these films more affirming than depressing: cathartic experiences, I imagine, that depicted and validated the challenges of their everyday difficulties. The mere existence of such a broad film schedule speaks to an artistic endurance that filmmakers and audiences both celebrated. About 30 percent of Ukrainian movie theaters have “closed or disappeared” in the last year of hostilities, Sinkyevich told me. Her Odessa Festival survived this year, barely, thanks to the kindness of others: she received extensive financial and organizational support from other Western European film festivals.

While this year’s crop of films made it through production and onto programs at Odessa, Cottbus, and elsewhere, Sinkyevich thinks next year’s harvest will be more constricted. Amid the current upheaval, filmmaking may be an unaffordable luxury. Russians, waiting for the other shoe to drop after Western sanctions, expressed similar fears about their film industry in the face of expected economic contraction. Part of the excitement at this year’s Russian and Ukrainian programs was, sadly, that this might be their last hurrah, at least for a while.

●

The Cottbus Festival does a laudable job of facilitating vital European dialogues. It’s particularly appropriate for Germans to be hosting such a program, because there, in the former DDR, one is supremely inclined to hope that twentieth-century Europe’s tragedies may have been resolved; people have recovered; and, informed by the horrifying lessons of the past, people are moving forward with enlightened optimism. Stumbling into Berlin’s “Mauerfall 25” celebrations was for me such a perfect pièce de résistance.

But even as the crowds basked in the lights of freedom at Brandenburg gate there was a sour note, tempering our complacency about having eradicated totalitarianism and vanquished a stalemate of geopolitical belligerence. Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader and a guest of honor at Berlin’s ceremonies, warned that current tensions between Russia and the West have moved the world to “the brink of a new Cold War.” It was just a quick sound bite, overshadowed by the festive outpouring, but still it was an ominous warning.

Again and again—after the Great War, after World War II, after the Holocaust, after the Cold War, after Sarajevo and Srebrenica and South Ossetia and Kosovo—people wanted to believe that the cycles of conflict were over, and that the borders and treaties were finally fixed in ways that would allow Europeans to move forward peacefully. Today’s newsfeed indicates otherwise. Cottbus’s films, documents from the front lines of a dangerously volatile eruption, show with piercing pathos the kind of simple, precise peril that W. H. Auden identified in his 1938 sonnet sequence “In Time of War”: “maps can really point to places / Where life is evil now.”

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.