Listen to an audio version of this essay here.

An acquaintance of mine, a comedy writer, once admitted to feeling disappointed that she hadn’t won any awards or recognition for her work, even though she also admitted not having done much to deserve it. We were listening to music at a local venue with a destroy fascism sign on the wall, and I remember thinking mockingly about the irrationality of my artsy friends. But when I started to tell the story to a publishing colleague during a lunch date in the park the next week, I realized that I too was living with the same quiet and ever-present disappointment—the sense that everyone around me was climbing some indescribably crucial ladder, without having much memory of why we had started climbing or what it was we hoped to find at the top. I complained, to myself and sometimes to others, that I hadn’t yet had any promising conversations with publishers who wanted to buy my book, despite the fact that I hadn’t spent much time thinking about what my book even was and had certainly not written any of it.

It helps, and makes sense, to recognize that the ladder is a sham. Maybe I hadn’t published a book yet because I spent every free moment I had on Twitter, but maybe it was also because the media industry is toxic and exploitative and full of nepotism. The latter was the argument of n+1’s summer editorial, “Critical Attrition,” which lamented that the critic today, burdened with debt and balancing multiple jobs, can no longer be counted on to give readers an honest, good-quality review. The main problem, according to the editorial, is that “the contemporary American book review is first and foremost an audition—for another job, another opportunity, another day in the content mine.” The book critic’s life is so precarious that she takes on every assignment solely with the hope that one of her reviews will go viral and land her a job interview with a professor: in the meantime, she rides her bike to her part-time job and so is prone to accidents and health-insurance crises; she uses Google Docs because she can’t afford Word. If she doesn’t take on that seven-hundred-word review that she dreads, then she worries that “her career has stalled, that she hasn’t accomplished enough, that no publisher will buy her next book and everyone—her editor, other writers, her friends—will forget she exists.”

To ask of this alarming depiction of the literary career why the reviewer can’t pick up a book and read it for the sake of reading, or why she can’t take the subway to work, or which college professor is scouring “viral” essays for their next hire, or which literary magazine is so prestigious that not writing for it would cause her to cease to exist, would be insensitive—and maybe it would miss the larger point. Perhaps the editorial’s somewhat cynical but mostly just dull portrait of the writing life is unavoidable, given that “careerism”—as the critic Christian Lorentzen noted last spring in his review of a new Philip Roth biography for Bookforum—is “the dominant literary style in America.”

For Lorentzen, this was less an accusation than an observation. Roth’s “exquisitely managed career”—including his good sense to die at just the right time—was an “inevitability, the zeitgeist of his generation” of meritocracy, and could serve as a model from which today’s writers could learn a thing or two (like “listen to critics while scorning them publicly,” which seems a fair description of how we might use social media). Moreover, careerism as an ideal was hardly unique to the lives of writers. In an ensuing panel discussion, Lorentzen suggested that careerism was also “the dominant style of American life.” With television, mass media and now the internet, public-image management is simply a “part of the job” of not just creative work but all aspects of social and professional life today.

But Lorentzen made a further point: image management was not only an obligatory aspect of the writer’s life but was also, increasingly, creeping “into the writing of fiction itself.” “The more readers (and critics) are content to conflate alter egos with authors,” Lorentzen wrote, “the more authors are tempted to idealize their fictional selves: confessional literature cedes the field to the autofiction of self-flattery.” In this light, the n+1 editorial can be seen as one member of a larger genre of recent literature—a genre spanning fiction, nonfiction and literary criticism—that seems intent on foregrounding precisely the ugliest aspects of literary life. There is undeniably, in these books, honesty and sincerity about the disappointments and compromises that are involved in that life, and the popularity of the genre’s headliners—especially within the literary world—attests to the resonance of the theme. Yet it is worth wondering why so many writers and readers are so attracted to books that paint such an unremittingly bleak picture of what we spend our lives doing.

●

In a world already disenchanted by late capitalism, Trump, climate change, the patriarchy, the resistance to the patriarchy, racism, the resistance to racism, virtue signaling generally, and the internet, it is striking how many of the most talked-about books in this genre appear intent on proving, usually via a young, female protagonist who is interested in becoming an author, that reading and writing are part of the problem.

Throughout much of Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World, Where Are You, writing for a living is presented, at best, as a mercenary occupation that is “morally and politically worthless.” Alice Kelleher, a famous Irish novelist who is recovering from a breakdown suffered from her instant fame and visibility, reminds her friend Eileen that she only wrote her first book “to make enough money to finish the next one,” but in fact “it’s nothing, it makes me miserable, and I don’t want to live this kind of life.” As the novel unfolds, she seeks an escape from the indignities of her fame in a relationship with a man whose chief virtue seems to be that he doesn’t read—her books or anybody else’s. Alice’s story ends with a defense of writing and beauty, as she begins a new book in the midst of a worldwide pandemic while acknowledging it will do little to address mass immiseration. Yet the balance of Rooney’s novel is taken up with Alice contemplating the many ways that her success as a writer has made her miserable.

Dorothy, the adjunct professor at an unnamed New York City university and the protagonist of Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind, also sustains herself through a mockery of the kind of success she desperately wants. Life’s promise has disappointed; her future doesn’t hold the possibility of fame or tenure or publishing, and her colleagues and advisor are largely to blame. She can’t bear to watch colleagues who actually look interested in what they’re doing; indeed, the simple pleasure of reading a book and taking longhand notes with a fountain pen looks to her like a “pantomime of success.” Dorothy herself spends her time actively avoiding reading, which she doesn’t seem to enjoy anymore, constantly picking up a book and then immediately putting it down and picking up her phone instead.

The actually passionate characters in Smallwood’s story are, to Dorothy, hateful. One of the book’s strangest and most moving details is the thesis subject of one of her colleagues, an academic celebrity in the making who is writing about the role of doors in Victorian novels. Dorothy’s bitterness about her own stagnant career is tied up with her bitterness about Alexandra’s success, which is bewildering to Dorothy because of this apparently ridiculous research interest. Dorothy’s bewilderment at her situation largely stems from Alexandra’s success despite her mediocre intellect—and she makes no secret of her contempt. She’d assumed that Alexandra had “some theory about the meaning of doors,” but when she realizes that Alexandra “was really interested in—doors,” Dorothy is genuinely stumped. “Alexandra expounded on the subject of—doors. Not what they were about. Just that they were.” Presumably the reader is supposed to share Dorothy’s view that Alexandra’s research is ridiculous and mockable, but what is truly depressing is not this caricature of disciplinary overspecialization but the fact that Dorothy herself doesn’t seem to be interested in writing about—anything. In place of any exciting alternative to nineteenth-century doors, Smallwood offers only the spectacle of a mind fixating on its career disappointments as an adjunct professor.

Lauren Oyler’s protagonist in Fake Accounts is another young female writer who, like Dorothy, has no intimacy with her own work and scorns both success and the fact that she wants it. The only thing she contributes to her magazine, she says, is that she knows how semicolons work, yet in the same breath she claims she expected to be offered a raise when she handed in her resignation. She mocks her colleagues who stay because “they felt ultimately ‘lucky’ to have writing jobs in media,” and moves to a country she doesn’t care to know anything about or want to live in because “it just didn’t seem like it was going to happen for me in New York, it being it, resounding, highly publicized success, or rather I didn’t care to do what was necessary to make it happen for me—work very hard.” Like Alice and Dorothy, Oyler’s narrator both decries and reinforces the idea that we only exist through this form of shallow, ugly recognition.

Both Oyler’s and Smallwood’s protagonists convey the overwhelming feeling of being stuck. Dorothy describes the “ordinary, odorous, calendrical drip” of her life, in which “waiting time was agony” but also admits that, without publishing her thesis or getting hired at a more prestigious university, life is “something you did just to pass the time.” Oyler’s character dismisses her own narration, saying, “To be clear: I know this is boring,” and reiterating later, “This is boring. I know that.” Other people are no better—she decides that “everyone around me was boring, more boring than even the most boring person I could make up.”

Likewise, Jia Tolentino, in her essay collection Trick Mirror, declares that the only acceptable way to become famous is by writing a book, but also that writing “is either a way to shed my self-delusions or a way to develop them.” In other words: Who cares what the difference is between clarity and deception, or whether the point of writing is truth or lies? Such questions, she seems to be saying, are naïve and uninteresting. The writing life poses the ultimate dilemma of hypocrisy: “To articulate this desire to vanish is always to reiterate the self once again.”

In Tolentino’s reading, there can be no sincere way of caring intensely about something in the world completely outside oneself without being self-deluded, without making oneself the real focus. She therefore acknowledges her “complicity” over and over in her writing, achieving the only kind of (compromised, of course) authenticity that is available to her by expositing on how truth and authenticity are impossible. Rooney’s commercial success seems likewise inextricably tied to her denunciation of commercial success, whether through the author-character in her novel or in her interviews outside of it. In the mode of careerism that shows up in these books we must both want fame and also want to denounce our desire for fame, just as in this mode of morality we must both want to be good and also denounce our desire to be good.

The cynicism of these books is understandable. The gig economy sucks and capitalism sucks and Twitter sucks and nepotism and schmoozing suck, so it makes sense that the fiction and cultural criticism that resonate with us reflect this experience of dissatisfaction. But in wanting to “anticipate the reader,” as Oyler told one interviewer she intended to do, all this writing risks merely adding the experience of reading and writing to this long list of things that suck. Of course it’s terrible to work under these shitty circumstances—but what is the point of working under these shitty circumstances if the circumstances become all we can write about?

●

For a long time I assumed, without a doubt and without an ounce of irony, that once I had made it to New York the bulk of my life’s work in New York was already done, that now it was only a matter of time before I too was working as a cool literary editor at a swanky national magazine, or becoming my generation’s most famed controversial feminist, engaging in irrefutable commentary on Twitter and having important conversations with agents about my book. I had only to arrive, and to live up to the picture of this literary person who tore through her stack of New Yorkers and was feverishly talked about, and then somehow the waiting would simply be over. Of course, this never happened and could never have happened; instead, the waiting continued while I read one book after another about women who, although more successful than me, were nonetheless similarly aggrieved about the mismatch between their image of their work life and its day-to-day reality. They reflected my own growing disenchantment about my career, but they also helped to shape it; they were fervently read and discussed by everyone in the profession whom I respected, and so they fed into the way I understood and set expectations for the writing life for myself.

In one of my first magazine jobs after I got to New York, I contributed to a series of articles about the nature of work culture and the ways it’s tyrannical and essentially meaningless. There’s a well-trodden argument—which I believe in, and which I too have written about, several times—about the need to de-normalize the “love what you do” messaging. Mostly jobs suck and are corrupt and will not guarantee us a secure or debt-free life, and work culture is a shallow and rigged system that only inspires passion if you’re deluded or hypocritical.

But the more time I spent with this idea, the more I personally began to feel depleted of a passion for anything at all. I was happy to be redeemed, politically, for disliking my job—and we all ought to be allowed to dislike our jobs and to say as much—but I didn’t actually want to dislike my job. It is important to decry work culture, but what about the fact that we all work? And what about the fact that in order to decry work culture importantly and publicly, we were all obviously finding the motivation and the inspiration to work hard, to maintain the discipline required to write? We must have done it, and continue to do it, because we like writing, and we’d like to put in the effort and produce work that we’re proud of and that other people appreciate and retweet (a perfectly acceptable thing to want, as long as it is not the only thing we want). We all had our political stance and this wasn’t a secret, but we also all had writing careers, and no one was asking how this works, how it really feels to write every day for a living of any kind, how this hard and ugly and exhausting thing is sustained every hour of every day.

There is a contradiction here of both scorning a system that’s shallow and rigged, and also feeling bitter about not being able to succeed within such a system in order to get our remuneration. The self-absorption and boredom reflect an expectation that a successful and stimulating life was somehow deserved. It made me realize that the conversation I was having with myself and others about the meaninglessness of work was pointless if I wasn’t able to offer myself something else meaningful in its stead. Desiring so much out of a system I hated was making me impossible to satisfy.

●

My first memory of really snapping out of my low-functioning state of distaste with the New York careerism that I’d failed at but still grudgingly admired was when my husband mentioned offhand that his roommate had begun, uncharacteristically, to read a book of Bukowski’s poetry that had been left lying around the apartment. “A lot of my friends have suddenly started to read a lot more and become interested in new things,” he said thoughtfully. Many of his friends were musicians and artists and from what I gathered not particularly engaged with much reading outside their comfort zone. “I think we’ve all started to realize…we’re in our thirties, our arts careers are what they are, and this life is what it is. Now is as good a time as any to commit to something.”

What he was describing was a slow and perhaps unconscious understanding that “success” meant only so much, and that its meaning would do well to become more flexible as we approached middle age. We all wanted to be high-functioning and successful, and we all wanted to create a society where that would not be as hard as it is now, but this life was what it was; our jobs might be somewhat unfulfilling, but this did not mean that all work had to be, or that we couldn’t enjoy ourselves anyway. Our hours had to be filled with something else besides idealism about a world where fulfillment would be possible only in the future.

My cynicism about the careerist aspects of becoming a successful writer was the mirror image to my original idealized portrait of the literary life. When it turns out that in reality this life is mostly ugly and corrupt and difficult and crappy, and that the world will probably keep making fools of us, the fantasy turns into a warped picture of the other extreme: the story of no work but careerism, of no jobs but bullshit jobs, of the reviewer-adjunct-writer in the n+1 editorial. This is a picture of such extreme resistance to a fantasy of the writer’s life that it becomes its own fantasy, one where the writing life is built on nothing but shallow notions of fame, success and ambition. Romanticizing the writing life and denouncing it are not so different; in both cases the thing that gets left out is why we actually live it.

Of course we have to manage our careers. Of course we publicize our work with self-effacing yet smarmy tweets. Of course we agonize over whether the list of publications we’ve written for is impressive enough or long enough to add a “bylines in” line to our Twitter bio without looking thirsty. Of course we schmooze or suck up to editors in whatever pathetic little ways we can. Who cares? This obsession with the indignity of managing of our careers is… undignified. And it distracts from whatever dignity remains in the work of writing.

Here’s the thing: we (by which I mean writers who are early-career, low-paid, freelance, unknown, whatever) know all about nepotism and backdoor agreements. We know about exploitation, about agonizing over concealing just how desperate we are, about holding our own in negotiating our rates if we even have the privilege to negotiate. We know about having a million side gigs. We know about spending so much time on a five-hundred-dollar article that we can’t bear to try to calculate how much we made per hour of work. And it doesn’t matter to us. It’s frustrating and tiresome, and it matters in the way student debt and seven years earning minimum wage matter, making a difference to where we live and how we eat and what we do at night. But it does not matter to the fact of our actual writing, to the fact that we write, to the thoughts we wrestle with when we read books and try to translate those thoughts into words on a page. When our editor rejects our pitch and instead gives the review to her celebrity-journalist friend, who then phones in a review that is obviously worse than what we would have written, or when another editor refuses to assign us an article about a youth protest, saying there is no room for the story, and we wake up the next morning to find they’ve run a story on the protest written by a fortysomething reporter, it doesn’t matter to us, not really. We gripe in our support groups, but we still write. We know all the reasons and more why the writing life isn’t worth it, and clearly none of them really matter because we still write.

●

Three years before Blake Bailey’s biography of Philip Roth, there had been another kind of Roth “biography.” In Lisa Halliday’s 2018 novel Asymmetry, Roth appeared as the fictional character Ezra Blazer. Roth’s character befriends Mary-Alice Dodge, a twentysomething editorial assistant at a publishing house (Halliday worked at a literary agency when she met Roth), and begins a surprisingly not-unpleasant affair with her, offering her unusually intimate insight into the day-to-day life of a famous author. Blazer visibly spends more time eating ice cream in Central Park than writing the next great American novel. He stops at Columbus Bakery every day for cookies, eats nectarines and drinks chocolate soy milk, tucks his cane into his belt as he struggles with his jacket zipper, buys Alice an air conditioner and piles of books and reminds her not to sentimentalize people, encourages her to write. He does things in the moment. “Choose this,” he tells her. “This is the adventure.” He talks through doors just for the silliness of it.

But even in Halliday’s novel, Blazer actually is spending most of the book behind his doors, slowly, patiently progressing through the pages of his book. He doesn’t engage in fervent “authorial image management,” but he is writing (and listening to the radio for Nobel Prize announcements), not just fooling around with his young protégé. This seems to be where the writing life really lives: behind the wooden doors that slip you wine and talk in Ezra’s voice. In his review of Roth’s biography, Christian Lorentzen wrote that “the work of a writer alone at his desk is impossible to dramatize, no matter how much shoulder pain the Olivetti causes.” This seems true enough. But while we may not be able to dramatize this work in writing, it would be a mistake to call writing an undramatic process.

Alice, too, quietly lives the writing life throughout the course of the book. She watches the cold-beer seller and the halal hot-dog seller and the girl in the bagel shop and the homeless man outside Zabar’s with a hundred coats on, even in the summer, and when Ezra tells her that she should write about herself she shakes her head and says the world is far more interesting than herself (which doesn’t at all read here like a self-deluded thing to say). One night during a blackout she goes up onto her roof and stares out over the Hudson “to confront the stars.” The moon, she sees, is “triumphant” against the darkness below; and “all at once it was no longer Céline’s moon, nor Hemingway’s, nor Genet’s, but Alice’s, which she vowed to describe one day as all it really was: the received light of the sun.”

Alice is lost in the way that any young person trying to make it in the New York literary world can get lost—she wants to write a novel and can’t imagine what she’s suited to write about, and she often seems to be drifting on autopilot—but she has moments of being enchanted by the world around her, and she feels the urge to engage with it in the present, even as her future as a writer remains as unclear as ever. She wanders into the sky, takes hold of the moon, and makes promises to it. Shortly after the blackout, she’s at a classical music concert with Ezra, where she is so moved by the pianist that the effect is “dazzling and demoralizing all at once: reverberating in her sternum, the music made her more desperate than ever to do, invent, create—to channel all her own energies into the making of something beautiful and unique to herself.”

She looks over at two young women she’d seen earlier, discussing “cagily” who would be chosen for their benefit concert’s solo, and realizes, “whatever they could do, it wasn’t this, would never be this, or would only become this once a great many more hours had been sacrificed to the ambition.” She distances herself from other young women, who are interested in success and fame and their careers just as Alice is. Ambition, she seems to be saying, cannot be built or rewarded with such a focus on other people: it only truly lives behind doors, at desks, past midnights, in the shoulder pain caused by the Olivetti.

Alice isn’t oblivious to the dull, sometimes ugly things we have to do to build a career, but if her relationship with Blazer is crucial to her success (he pays off her student loans), it’s also much more than that—and it doesn’t overshadow her relationship to her creative work (she becomes successful with a novel that pointedly disregards Blazer’s writing advice). Alice certainly isn’t not a careerist, with her defense of ambition, her “demanding to be remembered”; she doesn’t expect anything that she doesn’t demand. But the “highly publicized success” that Oyler’s character sneers at, or that Rooney’s Alice Kelleher thinks is a sickness, but that both characters (and authors) seem somehow to represent, is only an irrelevant distraction. This is the kind of success that Alice rejects, but she is still determined to live the writing life, to create something of meaning, to, as Ezra later describes it, “transcend her provenance, her privilege, her naiveté.”

In Halliday’s Alice we can see a middle ground between romanticizing and begrudging the work we put in every day to live and make a living as writers; between unspooling hours in the park and sacrificing hours to ambition, between making something that will earn you the moon, and submitting “to the loving of someone so deeply and well that there could be no question as to whether she were squandering her life.” This is the feeling of the writing life that our stories of careerism fail to capture: the feeling of reverberation in our sternums, of confronting the stars, dazzling and demoralizing all at once.

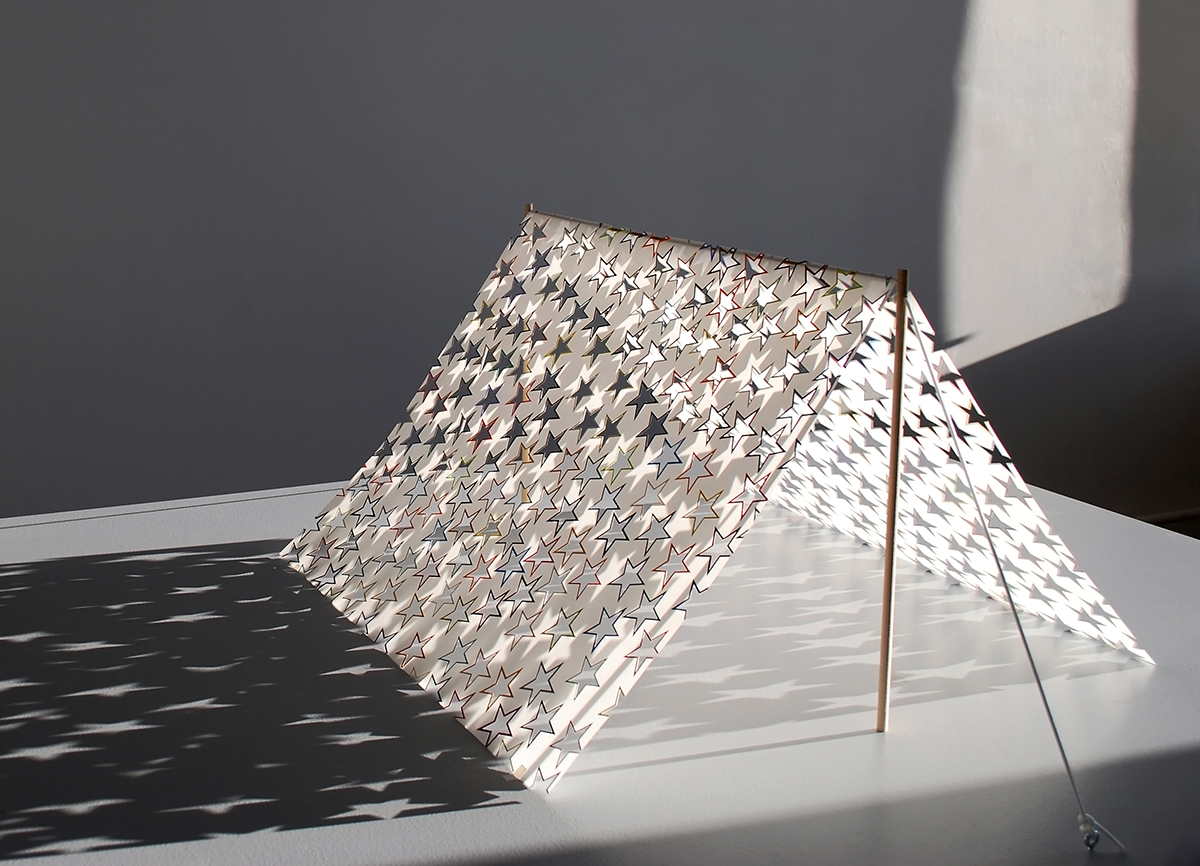

Art credit: Matthew Northridge. Twelve Ladders, or, How I Planned My Escape, wood, found image, 30 x 22 x 9 in., 2011; Shelter, mixed media, 13.75 x 22 x 39.5 in., 2017. All images courtesy of the artist.

Listen to an audio version of this essay here.

An acquaintance of mine, a comedy writer, once admitted to feeling disappointed that she hadn’t won any awards or recognition for her work, even though she also admitted not having done much to deserve it. We were listening to music at a local venue with a destroy fascism sign on the wall, and I remember thinking mockingly about the irrationality of my artsy friends. But when I started to tell the story to a publishing colleague during a lunch date in the park the next week, I realized that I too was living with the same quiet and ever-present disappointment—the sense that everyone around me was climbing some indescribably crucial ladder, without having much memory of why we had started climbing or what it was we hoped to find at the top. I complained, to myself and sometimes to others, that I hadn’t yet had any promising conversations with publishers who wanted to buy my book, despite the fact that I hadn’t spent much time thinking about what my book even was and had certainly not written any of it.

It helps, and makes sense, to recognize that the ladder is a sham. Maybe I hadn’t published a book yet because I spent every free moment I had on Twitter, but maybe it was also because the media industry is toxic and exploitative and full of nepotism. The latter was the argument of n+1’s summer editorial, “Critical Attrition,” which lamented that the critic today, burdened with debt and balancing multiple jobs, can no longer be counted on to give readers an honest, good-quality review. The main problem, according to the editorial, is that “the contemporary American book review is first and foremost an audition—for another job, another opportunity, another day in the content mine.” The book critic’s life is so precarious that she takes on every assignment solely with the hope that one of her reviews will go viral and land her a job interview with a professor: in the meantime, she rides her bike to her part-time job and so is prone to accidents and health-insurance crises; she uses Google Docs because she can’t afford Word. If she doesn’t take on that seven-hundred-word review that she dreads, then she worries that “her career has stalled, that she hasn’t accomplished enough, that no publisher will buy her next book and everyone—her editor, other writers, her friends—will forget she exists.”

To ask of this alarming depiction of the literary career why the reviewer can’t pick up a book and read it for the sake of reading, or why she can’t take the subway to work, or which college professor is scouring “viral” essays for their next hire, or which literary magazine is so prestigious that not writing for it would cause her to cease to exist, would be insensitive—and maybe it would miss the larger point. Perhaps the editorial’s somewhat cynical but mostly just dull portrait of the writing life is unavoidable, given that “careerism”—as the critic Christian Lorentzen noted last spring in his review of a new Philip Roth biography for Bookforum—is “the dominant literary style in America.”

For Lorentzen, this was less an accusation than an observation. Roth’s “exquisitely managed career”—including his good sense to die at just the right time—was an “inevitability, the zeitgeist of his generation” of meritocracy, and could serve as a model from which today’s writers could learn a thing or two (like “listen to critics while scorning them publicly,” which seems a fair description of how we might use social media). Moreover, careerism as an ideal was hardly unique to the lives of writers. In an ensuing panel discussion, Lorentzen suggested that careerism was also “the dominant style of American life.” With television, mass media and now the internet, public-image management is simply a “part of the job” of not just creative work but all aspects of social and professional life today.

But Lorentzen made a further point: image management was not only an obligatory aspect of the writer’s life but was also, increasingly, creeping “into the writing of fiction itself.” “The more readers (and critics) are content to conflate alter egos with authors,” Lorentzen wrote, “the more authors are tempted to idealize their fictional selves: confessional literature cedes the field to the autofiction of self-flattery.” In this light, the n+1 editorial can be seen as one member of a larger genre of recent literature—a genre spanning fiction, nonfiction and literary criticism—that seems intent on foregrounding precisely the ugliest aspects of literary life. There is undeniably, in these books, honesty and sincerity about the disappointments and compromises that are involved in that life, and the popularity of the genre’s headliners—especially within the literary world—attests to the resonance of the theme. Yet it is worth wondering why so many writers and readers are so attracted to books that paint such an unremittingly bleak picture of what we spend our lives doing.

●

In a world already disenchanted by late capitalism, Trump, climate change, the patriarchy, the resistance to the patriarchy, racism, the resistance to racism, virtue signaling generally, and the internet, it is striking how many of the most talked-about books in this genre appear intent on proving, usually via a young, female protagonist who is interested in becoming an author, that reading and writing are part of the problem.

Throughout much of Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World, Where Are You, writing for a living is presented, at best, as a mercenary occupation that is “morally and politically worthless.” Alice Kelleher, a famous Irish novelist who is recovering from a breakdown suffered from her instant fame and visibility, reminds her friend Eileen that she only wrote her first book “to make enough money to finish the next one,” but in fact “it’s nothing, it makes me miserable, and I don’t want to live this kind of life.” As the novel unfolds, she seeks an escape from the indignities of her fame in a relationship with a man whose chief virtue seems to be that he doesn’t read—her books or anybody else’s. Alice’s story ends with a defense of writing and beauty, as she begins a new book in the midst of a worldwide pandemic while acknowledging it will do little to address mass immiseration. Yet the balance of Rooney’s novel is taken up with Alice contemplating the many ways that her success as a writer has made her miserable.

Dorothy, the adjunct professor at an unnamed New York City university and the protagonist of Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind, also sustains herself through a mockery of the kind of success she desperately wants. Life’s promise has disappointed; her future doesn’t hold the possibility of fame or tenure or publishing, and her colleagues and advisor are largely to blame. She can’t bear to watch colleagues who actually look interested in what they’re doing; indeed, the simple pleasure of reading a book and taking longhand notes with a fountain pen looks to her like a “pantomime of success.” Dorothy herself spends her time actively avoiding reading, which she doesn’t seem to enjoy anymore, constantly picking up a book and then immediately putting it down and picking up her phone instead.

The actually passionate characters in Smallwood’s story are, to Dorothy, hateful. One of the book’s strangest and most moving details is the thesis subject of one of her colleagues, an academic celebrity in the making who is writing about the role of doors in Victorian novels. Dorothy’s bitterness about her own stagnant career is tied up with her bitterness about Alexandra’s success, which is bewildering to Dorothy because of this apparently ridiculous research interest. Dorothy’s bewilderment at her situation largely stems from Alexandra’s success despite her mediocre intellect—and she makes no secret of her contempt. She’d assumed that Alexandra had “some theory about the meaning of doors,” but when she realizes that Alexandra “was really interested in—doors,” Dorothy is genuinely stumped. “Alexandra expounded on the subject of—doors. Not what they were about. Just that they were.” Presumably the reader is supposed to share Dorothy’s view that Alexandra’s research is ridiculous and mockable, but what is truly depressing is not this caricature of disciplinary overspecialization but the fact that Dorothy herself doesn’t seem to be interested in writing about—anything. In place of any exciting alternative to nineteenth-century doors, Smallwood offers only the spectacle of a mind fixating on its career disappointments as an adjunct professor.

Lauren Oyler’s protagonist in Fake Accounts is another young female writer who, like Dorothy, has no intimacy with her own work and scorns both success and the fact that she wants it. The only thing she contributes to her magazine, she says, is that she knows how semicolons work, yet in the same breath she claims she expected to be offered a raise when she handed in her resignation. She mocks her colleagues who stay because “they felt ultimately ‘lucky’ to have writing jobs in media,” and moves to a country she doesn’t care to know anything about or want to live in because “it just didn’t seem like it was going to happen for me in New York, it being it, resounding, highly publicized success, or rather I didn’t care to do what was necessary to make it happen for me—work very hard.” Like Alice and Dorothy, Oyler’s narrator both decries and reinforces the idea that we only exist through this form of shallow, ugly recognition.

Both Oyler’s and Smallwood’s protagonists convey the overwhelming feeling of being stuck. Dorothy describes the “ordinary, odorous, calendrical drip” of her life, in which “waiting time was agony” but also admits that, without publishing her thesis or getting hired at a more prestigious university, life is “something you did just to pass the time.” Oyler’s character dismisses her own narration, saying, “To be clear: I know this is boring,” and reiterating later, “This is boring. I know that.” Other people are no better—she decides that “everyone around me was boring, more boring than even the most boring person I could make up.”

Likewise, Jia Tolentino, in her essay collection Trick Mirror, declares that the only acceptable way to become famous is by writing a book, but also that writing “is either a way to shed my self-delusions or a way to develop them.” In other words: Who cares what the difference is between clarity and deception, or whether the point of writing is truth or lies? Such questions, she seems to be saying, are naïve and uninteresting. The writing life poses the ultimate dilemma of hypocrisy: “To articulate this desire to vanish is always to reiterate the self once again.”

In Tolentino’s reading, there can be no sincere way of caring intensely about something in the world completely outside oneself without being self-deluded, without making oneself the real focus. She therefore acknowledges her “complicity” over and over in her writing, achieving the only kind of (compromised, of course) authenticity that is available to her by expositing on how truth and authenticity are impossible. Rooney’s commercial success seems likewise inextricably tied to her denunciation of commercial success, whether through the author-character in her novel or in her interviews outside of it. In the mode of careerism that shows up in these books we must both want fame and also want to denounce our desire for fame, just as in this mode of morality we must both want to be good and also denounce our desire to be good.

The cynicism of these books is understandable. The gig economy sucks and capitalism sucks and Twitter sucks and nepotism and schmoozing suck, so it makes sense that the fiction and cultural criticism that resonate with us reflect this experience of dissatisfaction. But in wanting to “anticipate the reader,” as Oyler told one interviewer she intended to do, all this writing risks merely adding the experience of reading and writing to this long list of things that suck. Of course it’s terrible to work under these shitty circumstances—but what is the point of working under these shitty circumstances if the circumstances become all we can write about?

●

For a long time I assumed, without a doubt and without an ounce of irony, that once I had made it to New York the bulk of my life’s work in New York was already done, that now it was only a matter of time before I too was working as a cool literary editor at a swanky national magazine, or becoming my generation’s most famed controversial feminist, engaging in irrefutable commentary on Twitter and having important conversations with agents about my book. I had only to arrive, and to live up to the picture of this literary person who tore through her stack of New Yorkers and was feverishly talked about, and then somehow the waiting would simply be over. Of course, this never happened and could never have happened; instead, the waiting continued while I read one book after another about women who, although more successful than me, were nonetheless similarly aggrieved about the mismatch between their image of their work life and its day-to-day reality. They reflected my own growing disenchantment about my career, but they also helped to shape it; they were fervently read and discussed by everyone in the profession whom I respected, and so they fed into the way I understood and set expectations for the writing life for myself.

In one of my first magazine jobs after I got to New York, I contributed to a series of articles about the nature of work culture and the ways it’s tyrannical and essentially meaningless. There’s a well-trodden argument—which I believe in, and which I too have written about, several times—about the need to de-normalize the “love what you do” messaging. Mostly jobs suck and are corrupt and will not guarantee us a secure or debt-free life, and work culture is a shallow and rigged system that only inspires passion if you’re deluded or hypocritical.

But the more time I spent with this idea, the more I personally began to feel depleted of a passion for anything at all. I was happy to be redeemed, politically, for disliking my job—and we all ought to be allowed to dislike our jobs and to say as much—but I didn’t actually want to dislike my job. It is important to decry work culture, but what about the fact that we all work? And what about the fact that in order to decry work culture importantly and publicly, we were all obviously finding the motivation and the inspiration to work hard, to maintain the discipline required to write? We must have done it, and continue to do it, because we like writing, and we’d like to put in the effort and produce work that we’re proud of and that other people appreciate and retweet (a perfectly acceptable thing to want, as long as it is not the only thing we want). We all had our political stance and this wasn’t a secret, but we also all had writing careers, and no one was asking how this works, how it really feels to write every day for a living of any kind, how this hard and ugly and exhausting thing is sustained every hour of every day.

There is a contradiction here of both scorning a system that’s shallow and rigged, and also feeling bitter about not being able to succeed within such a system in order to get our remuneration. The self-absorption and boredom reflect an expectation that a successful and stimulating life was somehow deserved. It made me realize that the conversation I was having with myself and others about the meaninglessness of work was pointless if I wasn’t able to offer myself something else meaningful in its stead. Desiring so much out of a system I hated was making me impossible to satisfy.

●

My first memory of really snapping out of my low-functioning state of distaste with the New York careerism that I’d failed at but still grudgingly admired was when my husband mentioned offhand that his roommate had begun, uncharacteristically, to read a book of Bukowski’s poetry that had been left lying around the apartment. “A lot of my friends have suddenly started to read a lot more and become interested in new things,” he said thoughtfully. Many of his friends were musicians and artists and from what I gathered not particularly engaged with much reading outside their comfort zone. “I think we’ve all started to realize…we’re in our thirties, our arts careers are what they are, and this life is what it is. Now is as good a time as any to commit to something.”

What he was describing was a slow and perhaps unconscious understanding that “success” meant only so much, and that its meaning would do well to become more flexible as we approached middle age. We all wanted to be high-functioning and successful, and we all wanted to create a society where that would not be as hard as it is now, but this life was what it was; our jobs might be somewhat unfulfilling, but this did not mean that all work had to be, or that we couldn’t enjoy ourselves anyway. Our hours had to be filled with something else besides idealism about a world where fulfillment would be possible only in the future.

My cynicism about the careerist aspects of becoming a successful writer was the mirror image to my original idealized portrait of the literary life. When it turns out that in reality this life is mostly ugly and corrupt and difficult and crappy, and that the world will probably keep making fools of us, the fantasy turns into a warped picture of the other extreme: the story of no work but careerism, of no jobs but bullshit jobs, of the reviewer-adjunct-writer in the n+1 editorial. This is a picture of such extreme resistance to a fantasy of the writer’s life that it becomes its own fantasy, one where the writing life is built on nothing but shallow notions of fame, success and ambition. Romanticizing the writing life and denouncing it are not so different; in both cases the thing that gets left out is why we actually live it.

Of course we have to manage our careers. Of course we publicize our work with self-effacing yet smarmy tweets. Of course we agonize over whether the list of publications we’ve written for is impressive enough or long enough to add a “bylines in” line to our Twitter bio without looking thirsty. Of course we schmooze or suck up to editors in whatever pathetic little ways we can. Who cares? This obsession with the indignity of managing of our careers is… undignified. And it distracts from whatever dignity remains in the work of writing.

Here’s the thing: we (by which I mean writers who are early-career, low-paid, freelance, unknown, whatever) know all about nepotism and backdoor agreements. We know about exploitation, about agonizing over concealing just how desperate we are, about holding our own in negotiating our rates if we even have the privilege to negotiate. We know about having a million side gigs. We know about spending so much time on a five-hundred-dollar article that we can’t bear to try to calculate how much we made per hour of work. And it doesn’t matter to us. It’s frustrating and tiresome, and it matters in the way student debt and seven years earning minimum wage matter, making a difference to where we live and how we eat and what we do at night. But it does not matter to the fact of our actual writing, to the fact that we write, to the thoughts we wrestle with when we read books and try to translate those thoughts into words on a page. When our editor rejects our pitch and instead gives the review to her celebrity-journalist friend, who then phones in a review that is obviously worse than what we would have written, or when another editor refuses to assign us an article about a youth protest, saying there is no room for the story, and we wake up the next morning to find they’ve run a story on the protest written by a fortysomething reporter, it doesn’t matter to us, not really. We gripe in our support groups, but we still write. We know all the reasons and more why the writing life isn’t worth it, and clearly none of them really matter because we still write.

●

Three years before Blake Bailey’s biography of Philip Roth, there had been another kind of Roth “biography.” In Lisa Halliday’s 2018 novel Asymmetry, Roth appeared as the fictional character Ezra Blazer. Roth’s character befriends Mary-Alice Dodge, a twentysomething editorial assistant at a publishing house (Halliday worked at a literary agency when she met Roth), and begins a surprisingly not-unpleasant affair with her, offering her unusually intimate insight into the day-to-day life of a famous author. Blazer visibly spends more time eating ice cream in Central Park than writing the next great American novel. He stops at Columbus Bakery every day for cookies, eats nectarines and drinks chocolate soy milk, tucks his cane into his belt as he struggles with his jacket zipper, buys Alice an air conditioner and piles of books and reminds her not to sentimentalize people, encourages her to write. He does things in the moment. “Choose this,” he tells her. “This is the adventure.” He talks through doors just for the silliness of it.

But even in Halliday’s novel, Blazer actually is spending most of the book behind his doors, slowly, patiently progressing through the pages of his book. He doesn’t engage in fervent “authorial image management,” but he is writing (and listening to the radio for Nobel Prize announcements), not just fooling around with his young protégé. This seems to be where the writing life really lives: behind the wooden doors that slip you wine and talk in Ezra’s voice. In his review of Roth’s biography, Christian Lorentzen wrote that “the work of a writer alone at his desk is impossible to dramatize, no matter how much shoulder pain the Olivetti causes.” This seems true enough. But while we may not be able to dramatize this work in writing, it would be a mistake to call writing an undramatic process.

Alice, too, quietly lives the writing life throughout the course of the book. She watches the cold-beer seller and the halal hot-dog seller and the girl in the bagel shop and the homeless man outside Zabar’s with a hundred coats on, even in the summer, and when Ezra tells her that she should write about herself she shakes her head and says the world is far more interesting than herself (which doesn’t at all read here like a self-deluded thing to say). One night during a blackout she goes up onto her roof and stares out over the Hudson “to confront the stars.” The moon, she sees, is “triumphant” against the darkness below; and “all at once it was no longer Céline’s moon, nor Hemingway’s, nor Genet’s, but Alice’s, which she vowed to describe one day as all it really was: the received light of the sun.”

Alice is lost in the way that any young person trying to make it in the New York literary world can get lost—she wants to write a novel and can’t imagine what she’s suited to write about, and she often seems to be drifting on autopilot—but she has moments of being enchanted by the world around her, and she feels the urge to engage with it in the present, even as her future as a writer remains as unclear as ever. She wanders into the sky, takes hold of the moon, and makes promises to it. Shortly after the blackout, she’s at a classical music concert with Ezra, where she is so moved by the pianist that the effect is “dazzling and demoralizing all at once: reverberating in her sternum, the music made her more desperate than ever to do, invent, create—to channel all her own energies into the making of something beautiful and unique to herself.”

She looks over at two young women she’d seen earlier, discussing “cagily” who would be chosen for their benefit concert’s solo, and realizes, “whatever they could do, it wasn’t this, would never be this, or would only become this once a great many more hours had been sacrificed to the ambition.” She distances herself from other young women, who are interested in success and fame and their careers just as Alice is. Ambition, she seems to be saying, cannot be built or rewarded with such a focus on other people: it only truly lives behind doors, at desks, past midnights, in the shoulder pain caused by the Olivetti.

Alice isn’t oblivious to the dull, sometimes ugly things we have to do to build a career, but if her relationship with Blazer is crucial to her success (he pays off her student loans), it’s also much more than that—and it doesn’t overshadow her relationship to her creative work (she becomes successful with a novel that pointedly disregards Blazer’s writing advice). Alice certainly isn’t not a careerist, with her defense of ambition, her “demanding to be remembered”; she doesn’t expect anything that she doesn’t demand. But the “highly publicized success” that Oyler’s character sneers at, or that Rooney’s Alice Kelleher thinks is a sickness, but that both characters (and authors) seem somehow to represent, is only an irrelevant distraction. This is the kind of success that Alice rejects, but she is still determined to live the writing life, to create something of meaning, to, as Ezra later describes it, “transcend her provenance, her privilege, her naiveté.”

In Halliday’s Alice we can see a middle ground between romanticizing and begrudging the work we put in every day to live and make a living as writers; between unspooling hours in the park and sacrificing hours to ambition, between making something that will earn you the moon, and submitting “to the loving of someone so deeply and well that there could be no question as to whether she were squandering her life.” This is the feeling of the writing life that our stories of careerism fail to capture: the feeling of reverberation in our sternums, of confronting the stars, dazzling and demoralizing all at once.

Art credit: Matthew Northridge. Twelve Ladders, or, How I Planned My Escape, wood, found image, 30 x 22 x 9 in., 2011; Shelter, mixed media, 13.75 x 22 x 39.5 in., 2017. All images courtesy of the artist.

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.