Listen to an audio version of this essay:

February 2017: my first winter in New York; the furthest I have ever lived from the equator. Getting out of bed is my finest accomplishment every day that I manage it. The stagnant air bleeds through the doorframe to the backyard and hovers in my room, staring at me in utter distaste. Later, I will recall these months as the first in my memory of having been forgotten by God.

The to-do lists cannot communicate with each other. I have a five-year plan that nags me every day, but none of it overlaps with the daily task list. Fretting about my supposed long-term goals of completing my book proposal and my novel takes up so much mental energy that basic jobs—paying bills even if I do have the money, filing taxes, changing the sheets, giving the university some document or other—become herculean tasks. I pull at single strands of my hair constantly, unrelentingly, an old habit that fills the ever-expanding moments I spend not doing the things on the to-do lists. The days are remarkably dark; I never knew that I would spend days not seeing the sun. In the dark, it becomes impossible to focus on what is important, and I fret, seized by a nameless fear, a nothing-tightness, that hugs my chest at all times. This nameless fear becomes the subject of much amicable conversation in my New York world, so different from the hectic world of underfunded nonprofits for low-income housing development that I left behind in Bombay. My Bombay life offered little time for self-analysis, and even less indication that I was important, and therefore little time for anxiousness about whether how we spent our time justified our importance; but here, this nameless fear becomes not only a constant internal presence but also, as a perennial subject of conversation, a kind of social currency. The feeling is so omnipresent it would be odd, almost inconsiderate, not to have it, like showing up at a white elephant party with no gift.

The conversations follow a familiar pattern: first, commiseration; second, a list of potential solutions for the nothing-tightness. Over and over it is hinted to me—in the healthy juices and exercise recommendations I’m offered, in the disapproving looks at my dollar pizza slices and late weeknight drinks, in the repeated insistence of how good meditation would be for me—that I’m not taking good enough care of myself. Better is not a word I have mulled over much before, being too preoccupied to really think of a future, but it is an important template now, a placeholder for whatever it is about my life that calls for change. In one of the graduate classes I came to New York to take, we are asked in an editing exercise to write a few sentences about how we have spent our recent days, and someone writes, I read Joan Didion and vowed to be better—and the sentence, just one in a list of beautiful statements about fever dreams and making amends and mushroom soup, floats around in my mind long after all the others I hear have gone. It echoes through the following months, as I mull over what being better looks like, unable to move dirty dishes from my desk to my sink.

I spend much of the winter of 2017 in bed, sometimes for days on end, evening after evening, scrolling through Instagram and looking at other people practicing self-care. I have an account that I visit, of a terribly banal celebrity, for what I tell myself is wellness inspiration: I spend hours watching her make fresh, wholesome green soups, moisturize her skin with watermelony things, go on hike after hike, experience infinite quantities of good vibes and express copious amounts of gratitude. My unbathed skin is fresh for a moment from her scented face washes; the dirty dishes piled on my desk are replaced for a moment with bowls of mush involving kale.

I have another account that I visit, of a terribly banal author, for what I tell myself is writing inspiration. I spend hours looking at her beautiful mahogany desk, her neat arrangement of notebooks, the sunlight spilling onto her bookshelf, and the porcelain teacups always poised next to her writing instruments. My disorganized papers, unread emails from editors and notebooks half-started with enthusiastic, overly ambitious, usually abandoned projects become, for a moment, resplendent with color-coded tabs and full story outlines, all my overdue writing projects suddenly falling into place.

During these winter months, I spend inordinate amounts of time looking at these uplifting images, and every once in a while I actually follow their advice on self-care routines, which I find is more time-consuming than simply watching people follow them, and only roughly as effective. I half-heartedly buy decorated life planners and journals, scented face scrubs, fresh vegetables listed on inspiring recipes, all of which languish unattended. The immediate gratification of living vicariously through other people on Instagram offers a momentary source of calm. It is, like self-care itself, an act of imagining that I’m close enough, so close, to my “real” goal; all that has to be done in order to be better is to make my desk organized and photogenic, to work out in attractive athleisure, to cook myself something healthy and beautiful. These are all ways to “be kind to myself,” which I am constantly being reminded I don’t do enough of, and they are all supposedly going to make the nothing-tightness go away.

When they do not, I take my project of being kind to myself to another level: I take to cocktails. These seem the most efficient self-care practice, at least until I switch to just whiskey (better value for money). After my seventh night in a row blacking out, I go to campus counseling.

I sit there in the office, filling out forms. I do not know what to do, how to be, here. I know only that I am anxious and do not know why. The therapist I am assigned tells me I have to take it slow, go easy on myself. One step at a time. Even if it’s something as small as getting up and moving your dishes from your desk to the sink, she says. That’s a feat too.

I take a deep breath and imagine getting up, just to move my dishes from my desk to the sink: just a minute, and then it will be over. I can do this, I think, and it will be a feat, an action of worth.

But I am not convinced that it should be—I am not convinced that getting out of bed should be a job I can say I accomplished, that going easy on myself is the best advice. Focusing on my own feelings about my life—the endless anxieties and provocations from the world—rather than about other things, seems to be distracting me, making me lose my ability to prioritize at all. I feel further than ever from being better.

●

Tax season, 2019: I make a pact with a friend. We are both going to complete tasks in the coming weeks, tasks we find intimidating, and by a deadline of our choice. We sign this pact in late January. My task is to file my taxes, something I have not done before in this country. Whoever breaks the pact owes the other two hundred dollars.

February comes and goes; I spend my evenings staying late at work and going home to watch Netflix, gearing up to sort through my paperwork and telling my mother to get off my back. March comes and goes; I spend my evenings after work at the library, working on my freelance projects and then going home to watch Netflix, gearing up to sort through my paperwork and telling my mother to get off my back. My mail builds up. April comes, and my mother offers to put me in touch with her accountant. I refuse, then agree. I spend an evening finding all the forms that have gotten lost in my mail, then feel exhausted. I send the forms to the accountant, send my friend two hundred dollars, and sleep off my shame all weekend.

In her popular BuzzFeed essay “How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation,” the journalist Anne Helen Petersen names my inability to complete such tasks “errand paralysis.” Errand paralysis is one of the “symptoms” of millennial burnout, she says, a tendency to push off “the mundane, the medium priority” tasks on our to-do list for months even while working hard in other aspects of our lives. Petersen’s article begins by alluding to a New York magazine piece on millennials who couldn’t find time to vote for president in 2016: Tim, a 27-year-old living in Texas, admits that mailing things gives him “anxiety”; Anna, a 21-year-old in New York, says she’d be “more inclined to vote” if it didn’t involve having to go to the post office. Were these failings personal, or was something more complicated happening? I cannot offer an honest reason as to why I couldn’t just get it together and complete the necessary task of filing my taxes, except to acknowledge that I was simply too lazy to learn how to do it, too lazy to do what was required to overcome my irrational fear of it. Petersen, on the other hand, reminds me that, like most freelancers, I need several jobs to stay afloat, and spend on average over eighty hours per week working. The “condition” uniting me with the twentysomethings who can’t mail in their votes, she assures me, is socioeconomic.

Petersen’s article draws heavily from Malcolm Harris’s 2017 book Kids These Days: The Making of Millennials. In his analysis of millennials’ experiences of school, university, the job market and the internet, Harris outlines the “structural” causes of our unhappiness. According to Harris, I am stressed and unmotivated because I am subjected to an economy that has commodified me; because at every point in my life I have been assessed and used for my labor. “People match their circumstance, and vice versa,” Harris writes. “The only way to understand who we are as a generation is to look at where we come from, and the social and economic conditions under which we’ve become ourselves.”

More than the self-care routines recommended to me by my friends and therapist, Petersen and Harris’s structural diagnosis makes instinctive sense to me. My academic career instilled in me a pedestrian suspicion of capitalism before I had any thoughts at all about New York or millennials or my own burnout. There is no refuting how inescapable capitalist ideology has become in our daily lives, or how important our economic realities are in defining how we are able to live—or the fact that we are indeed the blessed young who have inherited the national debt. The world does not seem to like my generation very much; constantly working for very little has become so normalized it borders on cliché.

And yet, Harris’s insistence that “the system is rigged” to make us fail, and the idea that we have adjusted so well to our economic situation that we cannot understand ourselves apart from it, inspires in me a sense of helplessness that is strangely similar to what I feel when my therapist recommends that I take it easy on myself. The unhappiness caused by our economy is real, but the endless, inward-focused conversations about it leave an unpleasant taste in my mouth, and no less anxiousness in my nerves. In “diagnosing” this condition, as if it were an illness that we need to stop denying the reality of, we risk oversimplifying things in much the same way we do when we imagine achieving salvation through self-care.

One evening, in a gritty Red Hook bar that we have sought out for its middle-aged clientele of retired uncles in khaki shorts, I am talking to a friend my age about our habit of waxing eloquent about our backbreaking workloads even though, somehow, we always seem to have time to waste. My friend, a city employee who has her wedding to pay for and her Ph.D. to complete before she will even let herself plan for the family she ultimately wants, has recently embarked on an immersive study of King Lear with her husband, partly to compensate for a week of binge-watching a pointless TV show. I offer her a vague comment about burnout, a wincing sympathy, while my insides shrivel in distaste with myself. “Burnout is real,” she says. “But sometimes I’m just being lazy! Just let me be lazy!”

●

“It has often been observed that revolt alone is pure,” Simone de Beauvoir writes in The Ethics of Ambiguity. I am now a researcher at a history magazine whose upcoming issue is about happiness, and I spend my days quietly in literature’s archives, holding séances with dead writers under my cubicle’s fluorescent light. From my little corner, carefully reading words from another time and place, I can sense the overwhelming urgency of the outside world dim and blur, becoming somewhat less real. Every construction implies the outrage of dictatorship, of violence, Simone laments. That is why … the negative moment is often the most genuine.

Simone’s half-century-old warning about the purity of revolt feels startlingly prescient to me here, among the New York progressives. The obsession with 21st-century American capitalism certainly gives us a template for understanding many of our experiences, including, perhaps, our inability to perform joyless but necessary tasks. But to believe revolt alone is pure, to find genuine feeling only in the negative moment, de Beauvoir argues, can lead to an objective moralism about our lives—the constant imperative to “resist” that comes to crowd out all our other ways of engaging with the world.

There is a moral value in being the victims of capitalism, of the American economy—especially when it enables us to come together as an oppressed group, unified by our experiences of burnout (now a medically recognized condition). But if we only see ourselves as the enemy of our enemy—as the resistance to capitalism—then we remain embedded in the ideology we critique, unable to escape. A tramp enjoying his bottle of wine, or a child playing with a balloon, or a Neapolitan lazzarone loafing in the sun in no way helps in the liberation of man, Simone chides. That is why the abstract will of the revolutionary scorns the concrete benevolence which occupies itself in satisfying desires which have no morrow. I shift in my seat guiltily. I have often, I realize as I slowly work through her fierce and patient sentences, made the mistake of scorning the “benevolence” of simple pleasure-seeking. I have, somewhere, imbibed the idea that optimism is unenlightened, irritating, laughably naïve and somehow beside the point when it comes to our supposed larger political goals.

One bright summer day I visit Bluestockings, a collectively owned bookstore and “activist center” in downtown New York, with a reading companion. It is truly a beautiful space, with an impressive collection of radical literature, zines and self-published manifestos; and yet something about it has always made me nervous. That day, a flyer on the window reminds readers of a talk or a book launch or a discussion happening that weekend: my memory of its subject matter is blurry, but the instruction, at the bottom of the flyer in small, endearingly childlike print, for white men to sit at the back and check their privilege, is distinct. My friend, a white man, hands the woman behind the counter a twenty-dollar bill for a small coffee, and is asked disdainfully if he needs change. We laugh at the ridiculousness of the question as we sit down. “They are saving the world, so how can I be attached to my change?”

We are joined an hour later by someone my friend knows, who is less dismissive of the barista’s attitude. He asks my friend whether he doesn’t feel a sense of guilt. “Sometimes, yes, when I know I have done something wrong,” my friend replies. “You mean you don’t walk around the world just feeling guilty?” his acquaintance repeats disbelievingly—and pointedly. “No,” my friend says, baffled. “So you’re literally a sociopath,” comes the perplexed, dead serious response.

It does, in fact, feel unusual to me to encounter someone who does not immediately relate to this feeling of inexplicable guilt, a sentiment so familiar to me as to seem natural. But I think there is something instructive about this ability to move through the world in a sane way, being kind without being overly apologetic, interrogative and curious instead of chronically unhappy, believing that a sense of fulfillment is within reach. My friend gives away his time and money to those who ask for it as though he has far more of both than he actually does, but he doesn’t declare it the moral obligation of a guilty white man—and so these actions, which bring him genuine joy, become lost here, in this space where our every experience is supposed to be freighted with resistance. Despite how many times the word “freedom” shows up in the titles of the books on these shelves, I get the sense that, in Bluestockings as in so many other of our social spaces, we’re creating a world where (just as Michel Clouscard said of neoliberalism) “everything is permitted but nothing is possible.”

It is understandable that we feel the need to undertake the “pure” revolt that de Beauvoir was describing: the revolt against our structural and socioeconomic conditions that cause suffering. But, especially given our long odds, we have to be careful while doing so not to abjure the very sense of agency that we would need to sustain such a revolt. Essential as the call for institutional change may be, we cannot undertake the steps to get there if we forget how to experience pleasure, on the way there and always.

In my frustration with the self-care narrative’s demand to achieve happiness, and the burnout narrative’s expectation not to, Simone becomes a relief during those clarifying days, a sane point of focus under the fluorescent cubicle light. I find myself drawn to those moments when she forgets to construct her enemy, forgets who her enemy is or even that it exists—and so forgets, remarkably, to “become her enemy’s enemy”: In order for the idea of liberation to have a concrete meaning, the joy of existence must be asserted in each one, at every instant, Simone reminds me. The movement toward freedom assumes its real, flesh and blood figure in the world by thickening into pleasure, into happiness.

●

Capitalism, as Harris and Petersen say, normalizes anxiety: it creates an industry of “happiness” and “self-care” that is invested in ensuring we’re never satisfied with our moods or ourselves. But narratives that blame all our unhappiness on capitalism normalize it too. They make us victims of capitalism twice: once for what is required of us by the American economy, and again for what is required of us by the narratives of “revolt” against the American economy.

If it is true that capitalism has made its way into our cellular systems, that we are products of the market, and that our lives are precarious because our livelihood so often depends on our constant availability—then the truth of all this only makes Simone’s assertions about the joy of existence all the more urgent. The individual as such is one of the ends at which our action must aim, she instructs, and not merely a member of a class, a nation, a collectivity:

If the satisfaction of an old man drinking a glass of wine counts for nothing, then production and wealth are only hollow myths; they have meaning only if they are capable of being retrieved in individual and living joy. The saving of time and the conquest of leisure have no meaning if we are not moved by the laugh of a child at play.

I hear this joy in the drunk uncle on the street calling out to me shamelessly and sincerely, God bless you, mami: when I stop to spend a moment in his company it is the detour that makes my movement an action of worth, one that makes us, like the child with the balloon or the lazzarone loafing in the sun, free for a moment together. To be happy now, with no greater purpose, seems too accidental to be considered political, but perhaps the true revolution will have some element of happy accident, the destination as a set of pleasurable detours. Perhaps it can sometimes be found in those moments when I truly own my time, my headspace; those rare and magnificent moments when I am not defining myself in relation to capitalism, when I forget to be my enemy’s enemy.

One evening after a glass of wine served in a mason jar at another bookshop full of manifestos, I fly into a rage toward a socialist I admire very much. We have just read a heartbreaking Andre Dubus story about a young couple who were not at all young anymore, who did not dance when they went out to dance and did not drive to the ocean they had come there to live near and could not think of anything to talk about other than their work and household chores, and who passed their hours reminiscing about when they were young, even though they were still young. I am sad, because it makes me sad to witness people’s passions quieten, love inevitably turning into habit. He is sad, because he believes that these young people work too hard, and if they had more money they would have a better relationship.

I find myself infuriated with this socialist friend, with his economic determinism—but also with his refusal to keep company with the characters from the story, to really hear what they are saying to him instead of merely assimilating it into the story he already thinks he knows. “Capitalism!” I say, thinking, ridiculously, of that smallest sliver of the universe where a tramp is contentedly drinking a glass of wine, “I’m so fucking sick of talking about capitalism!”

●

The language of self-care and the language of burnout may seem to be opposites, but often they can be complementary: the tendency to externalize our suffering to our economic and sociocultural circumstances provokes the counter-tendency to “take better care” of ourselves after being beaten down by those circumstances. Tossed from ideology to lifestyle statement, both stories threaten to turn us into passive victims, with little ability to interpret for ourselves what constitutes an action of worth, or to act accordingly.

I want to look, really look, at the world—but I find I do not want to look at it as an explanation for what is wrong with me. I don’t want to be forgiven. I want unkindness, from myself and from the world, because it is unkindness that has to be reckoned with, that makes me feel awake. I want to be punished; I want the stimulation of struggle. But it seems in order to do this I have to consider that the world does not owe me anything. I want to look at the world because despite the fact that it is unkind, it is also interesting, and full, and endlessly entertaining.

I forget this, during my worst winter and my most unmotivated months; I forget that there are stories to be chased that have nothing to do with me. I ask my therapist to help me remember these stories, these reasons to get out of bed in the morning. I ask her to help me re-want to learn about the world again—about literature, and philosophy, and ideas that continue to exist and exhilarate no matter how much money I have or will ever have, no matter how overworked I am and will certainly continue to be forever. She says that I am focusing on other things because I do not want to talk about myself: about how the boy I loved that winter had disappeared, about why I am fighting with my mother or about the fact that I am drowning in job applications. I need to do something nice for myself, she says, over and over again.

I take her advice, but for me, this so often involves running away from the work that, in its difficulty, keeps me sane. Left to my own devices, I will sit in bed and watch television all day in the name of self-care. I’m doing something nice for myself, I think, and I can feel myself drowning in this dangerous temptation. I finally tell myself I will remain stiff and conservative about my own happiness, until what feels right is something more objectively worthwhile, until focusing on myself escapes the lifestyle statement it has become and comes to involve something that is not me.

Under my little fluorescent light, I hunch over my desk long after everyone else has left the building, resisting both the temptation of the several nearby bars as well as the imperative of the free yoga trial that routinely presents itself to me helpfully on the shiny screen of my inbox. I am looking for some company I can trust. You can hear them better at night, my 84-year-old boss who is in the office more than anyone else, and who also conducts routine séances, once remarked. So I listen; and for me the listening stays the anxiousness in a way that “treat myself” mantras do not. We are told vehemently that self-care is not selfish, that we need to do more emotional work on ourselves and our inner lives; but the emotional lives of others, in all their complexities, sorrows, unwritten sentences in between written ones, enthrall me in a way my own never can.

Work has to be put in, I think as I leave the office, to not constantly work toward happiness; to not get so caught up in our own future satisfactions that we miss the ones that come to us now. Work has to be put in to realize de Beauvoir’s image of joy—that “concrete benevolence”—however fleeting it may be. It is, in its way, a political image, even if it neglects to relate itself to a structural analysis. And it illuminates my personal, individual experience of happiness without resorting to the language of therapy.

When I finally am able to leap out of bed in the morning, it is warmer, but it is also because I have found little pieces of the world to chase: Virginia Woolf’s secret pleasure of slipping out of her home after tea to wander all over London on the pretext of buying a pencil; Diane Arbus’s hollow, captivating eyes as she boards buses heading nowhere until finally someone offers to take her home; an impish letter from Walter Benjamin to Theodor Adorno about how the revolution can be heard in the obnoxious laughter at the cinema; the train ticket found in Camus’s pocket after the car crash and the genuinely loving letter written the day before to one of the many women he genuinely loved. These fragmented images of my loved ones’ inner thoughts, so real and so refreshingly different from the shiny, prescriptive images of self-love that fly to the surface of my phone, glimmer like the first rays of sunshine, like lives fully lived; they are company worth keeping. I focus on Walter and Virginia and Diane, on their images as they spin through my mind, chaotic and joyful and so wholly unrelated to me; and then, inexplicably, at least for the moment, I am being better, I am better.

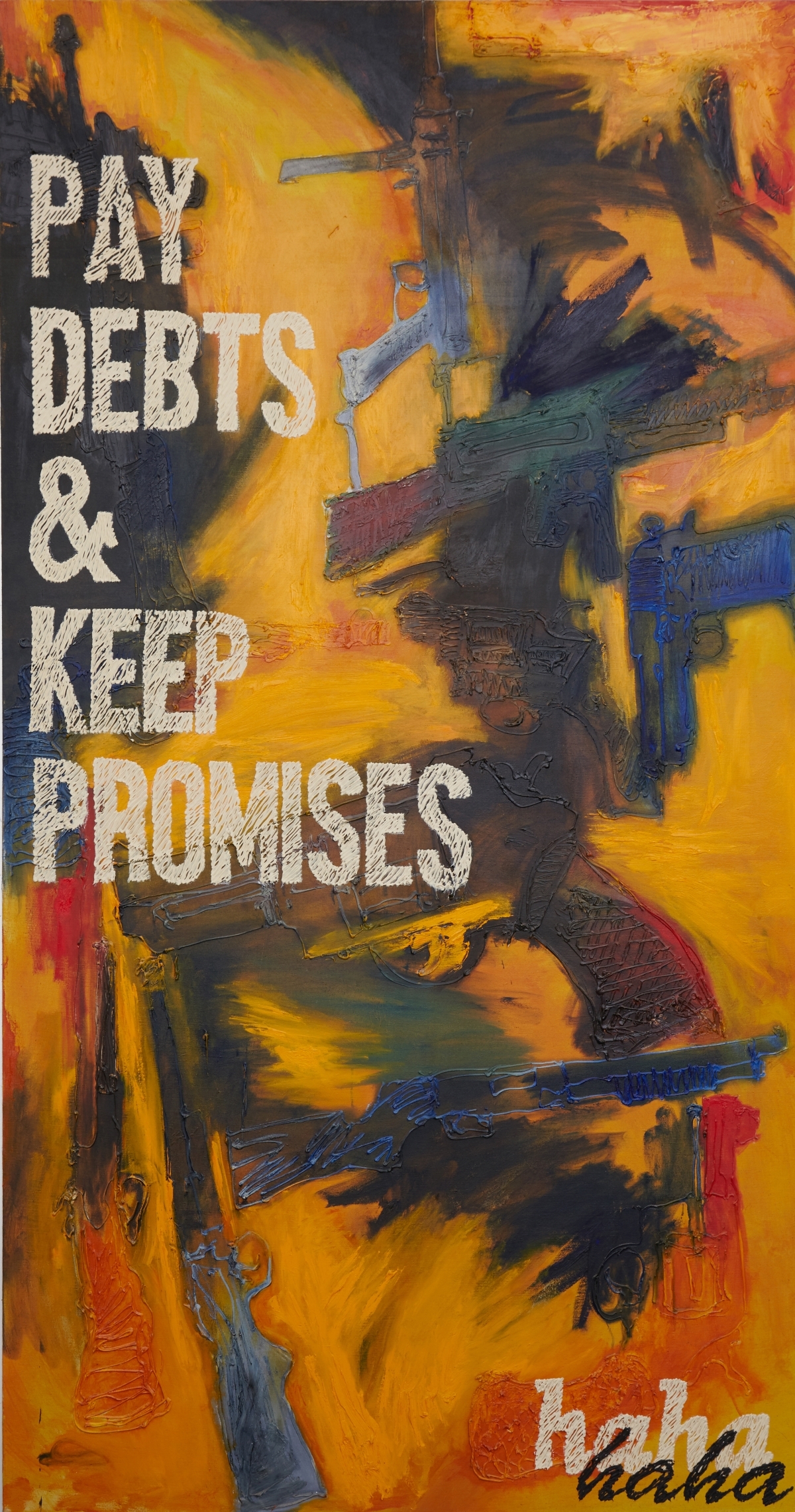

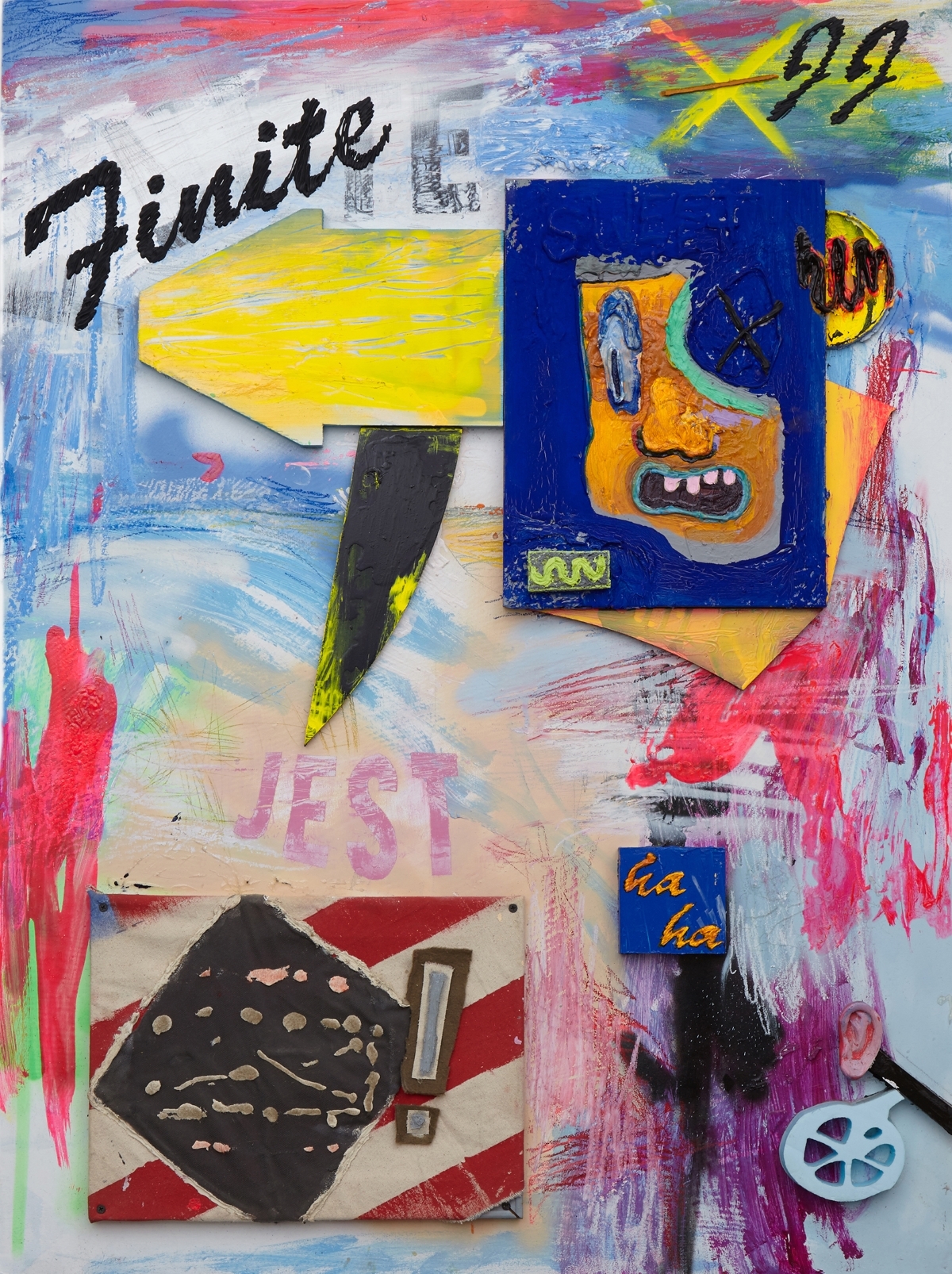

Art credit: Nic Rad, Victori + Mo Gallery

Listen to an audio version of this essay:

February 2017: my first winter in New York; the furthest I have ever lived from the equator. Getting out of bed is my finest accomplishment every day that I manage it. The stagnant air bleeds through the doorframe to the backyard and hovers in my room, staring at me in utter distaste. Later, I will recall these months as the first in my memory of having been forgotten by God.

The to-do lists cannot communicate with each other. I have a five-year plan that nags me every day, but none of it overlaps with the daily task list. Fretting about my supposed long-term goals of completing my book proposal and my novel takes up so much mental energy that basic jobs—paying bills even if I do have the money, filing taxes, changing the sheets, giving the university some document or other—become herculean tasks. I pull at single strands of my hair constantly, unrelentingly, an old habit that fills the ever-expanding moments I spend not doing the things on the to-do lists. The days are remarkably dark; I never knew that I would spend days not seeing the sun. In the dark, it becomes impossible to focus on what is important, and I fret, seized by a nameless fear, a nothing-tightness, that hugs my chest at all times. This nameless fear becomes the subject of much amicable conversation in my New York world, so different from the hectic world of underfunded nonprofits for low-income housing development that I left behind in Bombay. My Bombay life offered little time for self-analysis, and even less indication that I was important, and therefore little time for anxiousness about whether how we spent our time justified our importance; but here, this nameless fear becomes not only a constant internal presence but also, as a perennial subject of conversation, a kind of social currency. The feeling is so omnipresent it would be odd, almost inconsiderate, not to have it, like showing up at a white elephant party with no gift.

The conversations follow a familiar pattern: first, commiseration; second, a list of potential solutions for the nothing-tightness. Over and over it is hinted to me—in the healthy juices and exercise recommendations I’m offered, in the disapproving looks at my dollar pizza slices and late weeknight drinks, in the repeated insistence of how good meditation would be for me—that I’m not taking good enough care of myself. Better is not a word I have mulled over much before, being too preoccupied to really think of a future, but it is an important template now, a placeholder for whatever it is about my life that calls for change. In one of the graduate classes I came to New York to take, we are asked in an editing exercise to write a few sentences about how we have spent our recent days, and someone writes, I read Joan Didion and vowed to be better—and the sentence, just one in a list of beautiful statements about fever dreams and making amends and mushroom soup, floats around in my mind long after all the others I hear have gone. It echoes through the following months, as I mull over what being better looks like, unable to move dirty dishes from my desk to my sink.

I spend much of the winter of 2017 in bed, sometimes for days on end, evening after evening, scrolling through Instagram and looking at other people practicing self-care. I have an account that I visit, of a terribly banal celebrity, for what I tell myself is wellness inspiration: I spend hours watching her make fresh, wholesome green soups, moisturize her skin with watermelony things, go on hike after hike, experience infinite quantities of good vibes and express copious amounts of gratitude. My unbathed skin is fresh for a moment from her scented face washes; the dirty dishes piled on my desk are replaced for a moment with bowls of mush involving kale.

I have another account that I visit, of a terribly banal author, for what I tell myself is writing inspiration. I spend hours looking at her beautiful mahogany desk, her neat arrangement of notebooks, the sunlight spilling onto her bookshelf, and the porcelain teacups always poised next to her writing instruments. My disorganized papers, unread emails from editors and notebooks half-started with enthusiastic, overly ambitious, usually abandoned projects become, for a moment, resplendent with color-coded tabs and full story outlines, all my overdue writing projects suddenly falling into place.

During these winter months, I spend inordinate amounts of time looking at these uplifting images, and every once in a while I actually follow their advice on self-care routines, which I find is more time-consuming than simply watching people follow them, and only roughly as effective. I half-heartedly buy decorated life planners and journals, scented face scrubs, fresh vegetables listed on inspiring recipes, all of which languish unattended. The immediate gratification of living vicariously through other people on Instagram offers a momentary source of calm. It is, like self-care itself, an act of imagining that I’m close enough, so close, to my “real” goal; all that has to be done in order to be better is to make my desk organized and photogenic, to work out in attractive athleisure, to cook myself something healthy and beautiful. These are all ways to “be kind to myself,” which I am constantly being reminded I don’t do enough of, and they are all supposedly going to make the nothing-tightness go away.

When they do not, I take my project of being kind to myself to another level: I take to cocktails. These seem the most efficient self-care practice, at least until I switch to just whiskey (better value for money). After my seventh night in a row blacking out, I go to campus counseling.

I sit there in the office, filling out forms. I do not know what to do, how to be, here. I know only that I am anxious and do not know why. The therapist I am assigned tells me I have to take it slow, go easy on myself. One step at a time. Even if it’s something as small as getting up and moving your dishes from your desk to the sink, she says. That’s a feat too.

I take a deep breath and imagine getting up, just to move my dishes from my desk to the sink: just a minute, and then it will be over. I can do this, I think, and it will be a feat, an action of worth.

But I am not convinced that it should be—I am not convinced that getting out of bed should be a job I can say I accomplished, that going easy on myself is the best advice. Focusing on my own feelings about my life—the endless anxieties and provocations from the world—rather than about other things, seems to be distracting me, making me lose my ability to prioritize at all. I feel further than ever from being better.

●

Tax season, 2019: I make a pact with a friend. We are both going to complete tasks in the coming weeks, tasks we find intimidating, and by a deadline of our choice. We sign this pact in late January. My task is to file my taxes, something I have not done before in this country. Whoever breaks the pact owes the other two hundred dollars.

February comes and goes; I spend my evenings staying late at work and going home to watch Netflix, gearing up to sort through my paperwork and telling my mother to get off my back. March comes and goes; I spend my evenings after work at the library, working on my freelance projects and then going home to watch Netflix, gearing up to sort through my paperwork and telling my mother to get off my back. My mail builds up. April comes, and my mother offers to put me in touch with her accountant. I refuse, then agree. I spend an evening finding all the forms that have gotten lost in my mail, then feel exhausted. I send the forms to the accountant, send my friend two hundred dollars, and sleep off my shame all weekend.

In her popular BuzzFeed essay “How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation,” the journalist Anne Helen Petersen names my inability to complete such tasks “errand paralysis.” Errand paralysis is one of the “symptoms” of millennial burnout, she says, a tendency to push off “the mundane, the medium priority” tasks on our to-do list for months even while working hard in other aspects of our lives. Petersen’s article begins by alluding to a New York magazine piece on millennials who couldn’t find time to vote for president in 2016: Tim, a 27-year-old living in Texas, admits that mailing things gives him “anxiety”; Anna, a 21-year-old in New York, says she’d be “more inclined to vote” if it didn’t involve having to go to the post office. Were these failings personal, or was something more complicated happening? I cannot offer an honest reason as to why I couldn’t just get it together and complete the necessary task of filing my taxes, except to acknowledge that I was simply too lazy to learn how to do it, too lazy to do what was required to overcome my irrational fear of it. Petersen, on the other hand, reminds me that, like most freelancers, I need several jobs to stay afloat, and spend on average over eighty hours per week working. The “condition” uniting me with the twentysomethings who can’t mail in their votes, she assures me, is socioeconomic.

Petersen’s article draws heavily from Malcolm Harris’s 2017 book Kids These Days: The Making of Millennials. In his analysis of millennials’ experiences of school, university, the job market and the internet, Harris outlines the “structural” causes of our unhappiness. According to Harris, I am stressed and unmotivated because I am subjected to an economy that has commodified me; because at every point in my life I have been assessed and used for my labor. “People match their circumstance, and vice versa,” Harris writes. “The only way to understand who we are as a generation is to look at where we come from, and the social and economic conditions under which we’ve become ourselves.”

More than the self-care routines recommended to me by my friends and therapist, Petersen and Harris’s structural diagnosis makes instinctive sense to me. My academic career instilled in me a pedestrian suspicion of capitalism before I had any thoughts at all about New York or millennials or my own burnout. There is no refuting how inescapable capitalist ideology has become in our daily lives, or how important our economic realities are in defining how we are able to live—or the fact that we are indeed the blessed young who have inherited the national debt. The world does not seem to like my generation very much; constantly working for very little has become so normalized it borders on cliché.

And yet, Harris’s insistence that “the system is rigged” to make us fail, and the idea that we have adjusted so well to our economic situation that we cannot understand ourselves apart from it, inspires in me a sense of helplessness that is strangely similar to what I feel when my therapist recommends that I take it easy on myself. The unhappiness caused by our economy is real, but the endless, inward-focused conversations about it leave an unpleasant taste in my mouth, and no less anxiousness in my nerves. In “diagnosing” this condition, as if it were an illness that we need to stop denying the reality of, we risk oversimplifying things in much the same way we do when we imagine achieving salvation through self-care.

One evening, in a gritty Red Hook bar that we have sought out for its middle-aged clientele of retired uncles in khaki shorts, I am talking to a friend my age about our habit of waxing eloquent about our backbreaking workloads even though, somehow, we always seem to have time to waste. My friend, a city employee who has her wedding to pay for and her Ph.D. to complete before she will even let herself plan for the family she ultimately wants, has recently embarked on an immersive study of King Lear with her husband, partly to compensate for a week of binge-watching a pointless TV show. I offer her a vague comment about burnout, a wincing sympathy, while my insides shrivel in distaste with myself. “Burnout is real,” she says. “But sometimes I’m just being lazy! Just let me be lazy!”

●

“It has often been observed that revolt alone is pure,” Simone de Beauvoir writes in The Ethics of Ambiguity. I am now a researcher at a history magazine whose upcoming issue is about happiness, and I spend my days quietly in literature’s archives, holding séances with dead writers under my cubicle’s fluorescent light. From my little corner, carefully reading words from another time and place, I can sense the overwhelming urgency of the outside world dim and blur, becoming somewhat less real. Every construction implies the outrage of dictatorship, of violence, Simone laments. That is why … the negative moment is often the most genuine.

Simone’s half-century-old warning about the purity of revolt feels startlingly prescient to me here, among the New York progressives. The obsession with 21st-century American capitalism certainly gives us a template for understanding many of our experiences, including, perhaps, our inability to perform joyless but necessary tasks. But to believe revolt alone is pure, to find genuine feeling only in the negative moment, de Beauvoir argues, can lead to an objective moralism about our lives—the constant imperative to “resist” that comes to crowd out all our other ways of engaging with the world.

There is a moral value in being the victims of capitalism, of the American economy—especially when it enables us to come together as an oppressed group, unified by our experiences of burnout (now a medically recognized condition). But if we only see ourselves as the enemy of our enemy—as the resistance to capitalism—then we remain embedded in the ideology we critique, unable to escape. A tramp enjoying his bottle of wine, or a child playing with a balloon, or a Neapolitan lazzarone loafing in the sun in no way helps in the liberation of man, Simone chides. That is why the abstract will of the revolutionary scorns the concrete benevolence which occupies itself in satisfying desires which have no morrow. I shift in my seat guiltily. I have often, I realize as I slowly work through her fierce and patient sentences, made the mistake of scorning the “benevolence” of simple pleasure-seeking. I have, somewhere, imbibed the idea that optimism is unenlightened, irritating, laughably naïve and somehow beside the point when it comes to our supposed larger political goals.

One bright summer day I visit Bluestockings, a collectively owned bookstore and “activist center” in downtown New York, with a reading companion. It is truly a beautiful space, with an impressive collection of radical literature, zines and self-published manifestos; and yet something about it has always made me nervous. That day, a flyer on the window reminds readers of a talk or a book launch or a discussion happening that weekend: my memory of its subject matter is blurry, but the instruction, at the bottom of the flyer in small, endearingly childlike print, for white men to sit at the back and check their privilege, is distinct. My friend, a white man, hands the woman behind the counter a twenty-dollar bill for a small coffee, and is asked disdainfully if he needs change. We laugh at the ridiculousness of the question as we sit down. “They are saving the world, so how can I be attached to my change?”

We are joined an hour later by someone my friend knows, who is less dismissive of the barista’s attitude. He asks my friend whether he doesn’t feel a sense of guilt. “Sometimes, yes, when I know I have done something wrong,” my friend replies. “You mean you don’t walk around the world just feeling guilty?” his acquaintance repeats disbelievingly—and pointedly. “No,” my friend says, baffled. “So you’re literally a sociopath,” comes the perplexed, dead serious response.

It does, in fact, feel unusual to me to encounter someone who does not immediately relate to this feeling of inexplicable guilt, a sentiment so familiar to me as to seem natural. But I think there is something instructive about this ability to move through the world in a sane way, being kind without being overly apologetic, interrogative and curious instead of chronically unhappy, believing that a sense of fulfillment is within reach. My friend gives away his time and money to those who ask for it as though he has far more of both than he actually does, but he doesn’t declare it the moral obligation of a guilty white man—and so these actions, which bring him genuine joy, become lost here, in this space where our every experience is supposed to be freighted with resistance. Despite how many times the word “freedom” shows up in the titles of the books on these shelves, I get the sense that, in Bluestockings as in so many other of our social spaces, we’re creating a world where (just as Michel Clouscard said of neoliberalism) “everything is permitted but nothing is possible.”

It is understandable that we feel the need to undertake the “pure” revolt that de Beauvoir was describing: the revolt against our structural and socioeconomic conditions that cause suffering. But, especially given our long odds, we have to be careful while doing so not to abjure the very sense of agency that we would need to sustain such a revolt. Essential as the call for institutional change may be, we cannot undertake the steps to get there if we forget how to experience pleasure, on the way there and always.

In my frustration with the self-care narrative’s demand to achieve happiness, and the burnout narrative’s expectation not to, Simone becomes a relief during those clarifying days, a sane point of focus under the fluorescent cubicle light. I find myself drawn to those moments when she forgets to construct her enemy, forgets who her enemy is or even that it exists—and so forgets, remarkably, to “become her enemy’s enemy”: In order for the idea of liberation to have a concrete meaning, the joy of existence must be asserted in each one, at every instant, Simone reminds me. The movement toward freedom assumes its real, flesh and blood figure in the world by thickening into pleasure, into happiness.

●

Capitalism, as Harris and Petersen say, normalizes anxiety: it creates an industry of “happiness” and “self-care” that is invested in ensuring we’re never satisfied with our moods or ourselves. But narratives that blame all our unhappiness on capitalism normalize it too. They make us victims of capitalism twice: once for what is required of us by the American economy, and again for what is required of us by the narratives of “revolt” against the American economy.

If it is true that capitalism has made its way into our cellular systems, that we are products of the market, and that our lives are precarious because our livelihood so often depends on our constant availability—then the truth of all this only makes Simone’s assertions about the joy of existence all the more urgent. The individual as such is one of the ends at which our action must aim, she instructs, and not merely a member of a class, a nation, a collectivity:

I hear this joy in the drunk uncle on the street calling out to me shamelessly and sincerely, God bless you, mami: when I stop to spend a moment in his company it is the detour that makes my movement an action of worth, one that makes us, like the child with the balloon or the lazzarone loafing in the sun, free for a moment together. To be happy now, with no greater purpose, seems too accidental to be considered political, but perhaps the true revolution will have some element of happy accident, the destination as a set of pleasurable detours. Perhaps it can sometimes be found in those moments when I truly own my time, my headspace; those rare and magnificent moments when I am not defining myself in relation to capitalism, when I forget to be my enemy’s enemy.

One evening after a glass of wine served in a mason jar at another bookshop full of manifestos, I fly into a rage toward a socialist I admire very much. We have just read a heartbreaking Andre Dubus story about a young couple who were not at all young anymore, who did not dance when they went out to dance and did not drive to the ocean they had come there to live near and could not think of anything to talk about other than their work and household chores, and who passed their hours reminiscing about when they were young, even though they were still young. I am sad, because it makes me sad to witness people’s passions quieten, love inevitably turning into habit. He is sad, because he believes that these young people work too hard, and if they had more money they would have a better relationship.

I find myself infuriated with this socialist friend, with his economic determinism—but also with his refusal to keep company with the characters from the story, to really hear what they are saying to him instead of merely assimilating it into the story he already thinks he knows. “Capitalism!” I say, thinking, ridiculously, of that smallest sliver of the universe where a tramp is contentedly drinking a glass of wine, “I’m so fucking sick of talking about capitalism!”

●

The language of self-care and the language of burnout may seem to be opposites, but often they can be complementary: the tendency to externalize our suffering to our economic and sociocultural circumstances provokes the counter-tendency to “take better care” of ourselves after being beaten down by those circumstances. Tossed from ideology to lifestyle statement, both stories threaten to turn us into passive victims, with little ability to interpret for ourselves what constitutes an action of worth, or to act accordingly.

I want to look, really look, at the world—but I find I do not want to look at it as an explanation for what is wrong with me. I don’t want to be forgiven. I want unkindness, from myself and from the world, because it is unkindness that has to be reckoned with, that makes me feel awake. I want to be punished; I want the stimulation of struggle. But it seems in order to do this I have to consider that the world does not owe me anything. I want to look at the world because despite the fact that it is unkind, it is also interesting, and full, and endlessly entertaining.

I forget this, during my worst winter and my most unmotivated months; I forget that there are stories to be chased that have nothing to do with me. I ask my therapist to help me remember these stories, these reasons to get out of bed in the morning. I ask her to help me re-want to learn about the world again—about literature, and philosophy, and ideas that continue to exist and exhilarate no matter how much money I have or will ever have, no matter how overworked I am and will certainly continue to be forever. She says that I am focusing on other things because I do not want to talk about myself: about how the boy I loved that winter had disappeared, about why I am fighting with my mother or about the fact that I am drowning in job applications. I need to do something nice for myself, she says, over and over again.

I take her advice, but for me, this so often involves running away from the work that, in its difficulty, keeps me sane. Left to my own devices, I will sit in bed and watch television all day in the name of self-care. I’m doing something nice for myself, I think, and I can feel myself drowning in this dangerous temptation. I finally tell myself I will remain stiff and conservative about my own happiness, until what feels right is something more objectively worthwhile, until focusing on myself escapes the lifestyle statement it has become and comes to involve something that is not me.

Under my little fluorescent light, I hunch over my desk long after everyone else has left the building, resisting both the temptation of the several nearby bars as well as the imperative of the free yoga trial that routinely presents itself to me helpfully on the shiny screen of my inbox. I am looking for some company I can trust. You can hear them better at night, my 84-year-old boss who is in the office more than anyone else, and who also conducts routine séances, once remarked. So I listen; and for me the listening stays the anxiousness in a way that “treat myself” mantras do not. We are told vehemently that self-care is not selfish, that we need to do more emotional work on ourselves and our inner lives; but the emotional lives of others, in all their complexities, sorrows, unwritten sentences in between written ones, enthrall me in a way my own never can.

Work has to be put in, I think as I leave the office, to not constantly work toward happiness; to not get so caught up in our own future satisfactions that we miss the ones that come to us now. Work has to be put in to realize de Beauvoir’s image of joy—that “concrete benevolence”—however fleeting it may be. It is, in its way, a political image, even if it neglects to relate itself to a structural analysis. And it illuminates my personal, individual experience of happiness without resorting to the language of therapy.

When I finally am able to leap out of bed in the morning, it is warmer, but it is also because I have found little pieces of the world to chase: Virginia Woolf’s secret pleasure of slipping out of her home after tea to wander all over London on the pretext of buying a pencil; Diane Arbus’s hollow, captivating eyes as she boards buses heading nowhere until finally someone offers to take her home; an impish letter from Walter Benjamin to Theodor Adorno about how the revolution can be heard in the obnoxious laughter at the cinema; the train ticket found in Camus’s pocket after the car crash and the genuinely loving letter written the day before to one of the many women he genuinely loved. These fragmented images of my loved ones’ inner thoughts, so real and so refreshingly different from the shiny, prescriptive images of self-love that fly to the surface of my phone, glimmer like the first rays of sunshine, like lives fully lived; they are company worth keeping. I focus on Walter and Virginia and Diane, on their images as they spin through my mind, chaotic and joyful and so wholly unrelated to me; and then, inexplicably, at least for the moment, I am being better, I am better.

Art credit: Nic Rad, Victori + Mo Gallery

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.