In December 2005, in his fourth month as president of Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad called the Holocaust a myth. This was during an interview with Al-Alam, an Arabic-language channel broadcast from Tehran. The interview wasn’t an outlier. A year earlier, under new leadership, Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, the state-owned TV network that operates Al-Alam, broadcast a number of programs that described the Holocaust as a “made-up story,” a fiction or a myth. IRIB has always been hostile to what it calls the “Zionist Regime,” but prior to 2004 there had been no orchestrated campaign to cast the Holocaust as a lie.

Haroun Yashayaie is a past head of the Tehran Jewish Committee, an umbrella organization that oversees the administration of the city’s Jewish schools, kosher butcher shops and synagogues. A former film executive and newspaper editor, Yashayaie, who is 84, has always kept an eye on the media. When an IRIB channel labeled the Holocaust a fiction, he wrote an open letter in condemnation. When Ahmadinejad repeated the claim, he wrote another: “The Holocaust is, in fact, an open wound on the hands of Western civilization. … The Holocaust is not a myth in the same way that the massacre at Sabra and Shatila is not a myth.” After distributing the second letter to the media, Yashayaie personally delivered it to Ahmadinejad at a summit for religious minorities. The new president and his key cultural advisers were conflating criticisms of Israel with Holocaust denial, Yashayaie contended, and thereby whitewashing the crimes of fascism.

In both letters, Yashayaie emphasized that he had never been shy of publicly criticizing Israel. As a graduate student at the University of Tehran in 1967, he was one of the few students to speak out against the Six-Day War, publishing an open letter in Ferdowsi magazine titled “As a Jew I Am Ashamed.” At the time Iran and Israel were staunch allies, and in retaliation for his letter, Yashayaie says, he was summarily arrested and imprisoned by the Shah’s security forces. He protested that the rhetoric he had condemned concerned not Israel but rather “an ablution of neo-fascism.”

During his nineteen years as president of the Tehran Jewish Committee, Yashayaie met two of Ahmadinejad’s predecessors, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (1989-97) and Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005). He visited Rafsanjani on at least two occasions, and was received with open arms. “Rafsanjani was the most nonchalant cleric I ever met,” he says. Khatami attended a synagogue service in February 2004 at the invitation of the Jewish Committee, a “milestone” in Jewish relations with the Islamic Republic, according to Yashayaie.

Now retired, Yashayaie can still be found most days at his production company, Pakhshiran, on the sixth floor of what was once a white marble building in downtown Tehran, now soot-gray and surrounded by stores selling baby goods. This is where I visit Yashayaie weekly, mostly on Sundays, a day after Shabbat, which he prefers. The vintage movie posters lining the hallway to Pakhshiran’s door tell stories of car chases, thieves and quarreling neighbors. Inside, visitors can quickly spot Yashayaie’s office. On one side is a bookshelf that holds the company’s film prizes, including the Bronze Leopard at Locarno, and also a keffiyeh and prayer beads from Iran’s Supreme Leader. On the other side, photos of decaying landscapes frame the wall, recalling Iran of an earlier Persian era, when Yashayaie was born.

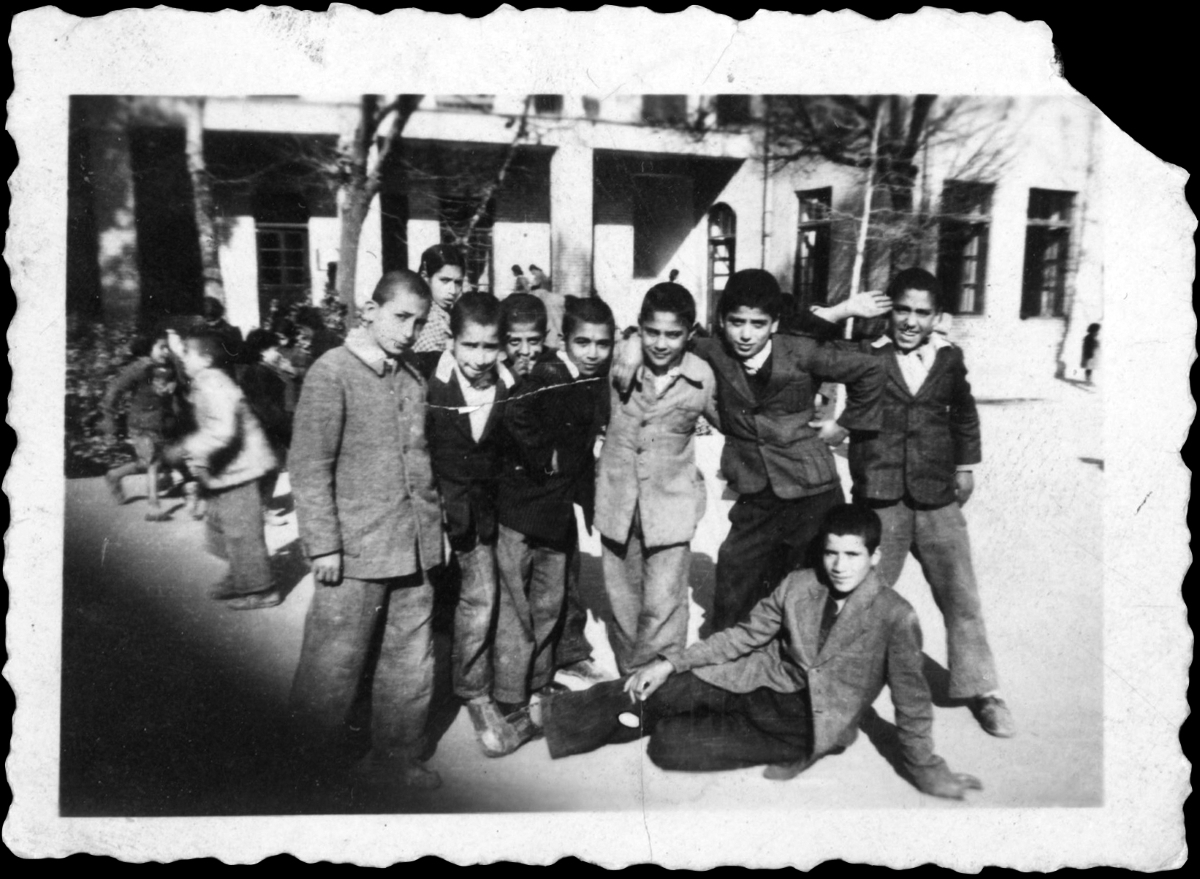

“I learned early on that the best way to address discrimination is out loud,” Yashayaie said when I first asked about his open letters on the Holocaust. He was referring to his student days in the Fifties at the French Jewish Alliance Française boys’ high school. Within walking distance was the headquarters of Iran’s national socialist party, SUMKA, founded by Davud Monshizadeh, a Nazi sympathizer who had lived and studied in Germany during the Third Reich. The SUMKA wore black shirts and armbands with a birdlike figure resembling a swastika. Barely numbering into the hundreds, they were known for attacking members of the Tudeh (Masses), Iran’s communist party. They also taunted Jewish girls, whose school was adjacent to the SUMKA office, by shouting anti-Semitic slurs as the students walked home.

“So,” Yashayaie said, “I joined the communist students from a nearby high school who came to fight the SUMKA.” He was eventually expelled from the Alliance for “hooliganism”—skirmishes with the SUMKA. Across those years and the more than fifty years that followed, Yashayaie would see the rise and fall of a national movement led by Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq, learn from the morning paper that his closest friends, prominent Marxists, had been executed in prison and lead one of Iran’s most successful advertising and movie production firms. With hundreds of others, he stood at the steps of the Air France plane that brought Ayatollah Khomeini to Tehran from Paris in 1979, a bouquet of flowers in his hands, declaring solidarity with the Revolution. A decade later he produced Hamoun, a film that elaborately explores an intellectual’s existential anxieties in a post-revolutionary age.

For someone like me, a post-1979 Iranian, Yashayaie represents a revolutionary movement that was open to membership across religious and political affiliations, and while opposing imperialist ambitions at home could still leave itself exposed to a questioning world. He is an embodiment of the diversity that made the transition of power in 1979 possible.

Near the end of many of our weekly conversations, I ask Yashayaie variations of the same question: How can one hold revolutionary idealism, the belief that collective action can lead to the betterment of society, to such lofty concepts as “equality” and “justice,” when the movement’s romanticism has long fizzled out? As he listens he holds a sugar cube between his teeth and sips tea loudly, a talent unique to men of the old teahouses.

“God created the world in six days, supposedly, and we are still trying to make it better,” he replied once, before taking down the Book of Genesis from his library and reading its depiction of the Fall. “Because man is inherently flawed—and will always be seeking change,” he proclaimed, his head of thick, wavy white hair as smooth and resilient as freshly piled snow on a rooftop. Every generation can find a place to seek improvement over the status quo, he insists. “The question is the decisions you will make if and when you find yourself in that place.”

●

Yashayaie regularly visits the office of the monthly literary magazine Bukhara to drop off manuscripts and have contentious conversations with Ali Dehbashi, Bukhara’s editor and his friend of thirty years. Usually their arguments end with Yashayaie yelling “salawat befrest!” (send peace upon Prophet Muhammad), calling for Dehbashi to calm down.

On this particular day we sit amid paper piles arranged on the floor like fortifications. Pen and paper in hand, Yashayaie draws a map of his childhood domain. Tehran’s Jewish Quarter, Oudlajan, where he lived, and Iran’s parliament in Baharestan Square have already been identified, as well as the street connecting them, which he walked at least twice a day. “It was the geography of my home that opened a window into Iran’s most turbulent years,” he says. He points to the location of Alliance, the girls’ school and the SUMKA headquarters all clustered near Baharestan Square.

“Baharestan is where he caught communism,” snorts Dehbashi, looking up from an article. A hardline newspaper has published a report calling him a freemason again—a baseless accusation that always makes a future publication ban more likely. Deshbashi hollers: “This is the legacy of the communists in Iran—they taught everyone how to carry out character assassination!”

Among the communist students Yashayaie met during his after-school fights with the SUMKA was his future business partner, Bijan Jazani, who was a leader of the Tudeh Party’s Youth Organization. Yashayaie was never formally a member of Tudeh, but he has long identified as a communist. He joined Jazani and other Tudeh youth in handing out the organization’s student newspaper and backing Mohammad Mossadeq’s Nationalist Front, a broad coalition of political organizations that supported Mossadeq’s call to independence.

When an oil nationalization bill was passed by parliament on March 15, 1951, and Mossadeq, a Swiss-educated law professor who was elected to parliament on a platform to bring Iran’s oil fields under public control, was elected prime minister the following month, Iran was euphoric. “Dr. Mossadeq’s charisma brought out a sense of national solidarity among all of us,” Yashayaie says. “We thought we could do anything—even face world powers.”

Both Britain and the United States were adamantly opposed to Mossadeq, fearing that his nationalization project would jeopardize their favorable oil concessions. Despite official negotiations with Mossadeq’s government, the British privately made clear to the U.S. that they would never agree to cede control of the flow of Iranian oil. When Mossadeq refused to capitulate, the British cabinet led an international embargo on Iran’s oil, the government’s primary source of income, and froze Iranian assets.

The ensuing economic turmoil did not remove Mossadeq from power, as the Americans and British had hoped, so they settled on a scheme privately backed by Iran’s monarch, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah, to overthrow him in a coup d’état. In the months leading up to the operation, various opposition groups, including the SUMKA party, were paid by the CIA to publish propaganda and stir up opposition to the government.

The operation was initially carried out on August 15, 1953, without success. Details had been leaked to Mossadeq through informants in the military, and he had put his chief of staff on alert. The Shah and his wife fled to Baghdad and then to Rome on a private plane. But the armed forces, aided and abetted by the CIA, turned the tide. By mid-afternoon on August 18th, with bands of looters and coordinated rioters ransacking shops, smashing windows and lighting fires at every street corner, army commanders drove their tanks into the city, and eventually toward Mossadeq’s home. Yashayaie, along with Jazani and other friends, was at Darvazeh Dowlat all day, one of old Tehran’s main gates a mile away from Baharestan. They were waiting for orders to “go to war,” he says—to attack coup supporters. The orders never came.

By late afternoon, Mossadeq had surrendered, and many in his administration had been taken into custody. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi returned to assume power. From the point of view of Yashayaie and the young communists, the monarch had returned to sit on a throne fully upholstered by imperialist powers. “The seed of the revolution was planted at that moment,” Yashayaie says. Mossadeq would be put under house arrest until his death in 1967. His fall was a fatal blow to the possibility of an Iranian path to a more democratic political process.

Among the Tudeh sympathizers who were arrested en masse after the coup, Jazani and Yashayaie were confined to Tehran’s Qasr prison. Within weeks of being released, however, both sat for the entrance exam for the University of Tehran’s philosophy department. Both were admitted. They also launched a company called Persepolis, Tehran’s first movie-advertising firm, serving the country’s nascent film industry. Jazani, an illustrator, designed advertisements that were photographed on film slides to be shown in theaters. Yashayaie and Jazani’s uncle distributed the slides to movie houses across Tehran that had never before screened ads.

While Yashayaie poured most of his energy into their business, Jazani, who had been raising a family since the time he was 25, had gone from being a high school youth organizer to a leading figure within the student movement at the University of Tehran. A generation of educated young people, the first in their family to attend university, joined guerrilla movements formed after the 1953 coup. Nearly four hundred were allegedly killed by SAVAK, the Iranian Intelligence and Security Organization established in 1957 with the help of the CIA.

By 1968, when he was imprisoned for the last time, Jazani was calling for armed resistance against the Shah. He had secretly co-founded a Marxist organization that had maintained enough recruits outside prison to remain operational, and in 1971 Jazani and the recruits joined another Marxist assembly to launch the Iranian People’s Fadaian Guerrillas. Jazani is widely considered the intellectual father of Fadaian, with many of his treatises, including The Thirty-Year History of Iran, distributed among young guerrillas, but he was executed overnight in 1975. The day Yashayaie saw news of Jazani’s death in the paper was “the absolute worst day of my life,” he recalls. It was claimed that Jazani and six other Fadaian, as well as two guerrillas from another militant group, were shot while trying to flee, but Yashayaie says he knew that was a lie—they were put before a firing squad.

Today, Yashayaie is often called upon as a witness and a footnote to the rise of leftist militancy in post-coup Iran. When I ask him how privy he was to Jazani’s relationship to the Fadaian, Yashayaie is coy, saying he and Jazani were best friends and business partners but that he “kept out” of Jazani’s politics. Instead he devoted himself to their company, which had by then expanded greatly to employ nearly three hundred people and changed its name to TabliFilm: “I told Bijan that even if you want to die, a burial requires cash, so I stuck to the business.” But TabliFilm’s large Tehran office turned into a hub for both leftist activists and artists, and was raided and eventually taken over by SAVAK.

As the media leads a new onslaught on the left and his fallen friends, Yashayaie has emerged as their defender, a mission for him as urgent as confronting Holocaust denial. “These were good kids in impossible circumstances. We can criticize their use of violence but the backdrop matters.” Privately, he points out how demeaning media coverage has only helped to boost the popularity of the old left in Iran and broaden the notion of what it had meant to be a revolutionary before the victory of the Islamic Revolution in 1979. For example, in May 2015, Mehrnameh, a monthly magazine of culture and politics, ran a disparaging profile of Jazani. On the cover, Jazani, painted in acrylic, looks straight ahead with a satisfied smirk. A blue hue outlines his body, and above his head it takes the shape of a gun. The phrase “The Terrorist Intellectuals” hovers in large letters by his shoulder. Magazines run covers with Jazani’s face on them because, no matter what they say about him, they know that it will sell. The very effort to condemn the left has etched it back into the grand collage of the revolution.

●

By 1975, the year of Jazani’s death, the Fadaian had taken note of the rise of the charismatic cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Other opposition groups had failed in taking direct aim at the Shah, Jazani argued, but that was precisely what Khomeini was doing. A marja, a Shi’a cleric of the highest religious authority, Khomeini became a widely known figure in 1963 after attacking the Shah’s political and land reforms. With Khomeini’s arrest, protests broke out in Tehran, where hundreds were reported to have been killed by the military. Yashayaie, who was on the streets with other university students during the demonstrations, remembers it as a major turning point in cementing Khomeini’s political prominence. Though clerics joined the tide of the anti-Shah protests, Yashayaie was still committed to what was then a nationwide movement. The challenges of a revolutionary Jew after the victory of an Islamic revolution would come later. “When the revolution finally came it was like a wave, you had to flow through,” he says.

Within a year, Khomeini, who had been released from prison, attacked the government for approving the “capitulation law,” which granted legal impunity to American military personnel stationed in Iran. “We are less than American dogs,” Khomeini said in a harshly worded speech. “To Allah, he is guilty of great sin who does not scream. … Is not our country under American occupation?” Khomeini was arrested and exiled first to Bursa, Turkey, and then for twelve years to Najaf, Iraq. As Khomeini was already a prominent marja, his exile only broadened his reach.

Among a new generation of student activists in Iran and abroad, Shi’a liberation ideology, inspired by both Shiism and anti-colonial struggles across the world, was gaining traction. Dissident clerics in confrontation with the Shah’s regime, like Mahmoud Taleqani, were galvanizing a movement that was strongly imbued with the language of Shi’a theology. Taleqani was a founder of the Freedom Movement of Iran, an offshoot of Mossadeq’s National Front, and a confidante of Khomeini’s. Taleqani and members of the Organization of Jewish Students, a left-leaning Jewish student body at the University of Tehran, of which Yashayaie was a founding member, had become acquainted while serving sentences in Tehran’s Qasr Prison.

In the summer of 1978, as anti-Shah protests were rapidly growing, Yashayaie was working with the board of directors at the Dr. Sapir Jewish Hospital. When riots broke out, injured protesters sought refuge there. As the Shah’s fall seemed imminent, Yashayaie and a group of eleven activists from the former Organization of Jewish Students, who now called themselves the Society of Jewish Intellectuals, declared their solidarity with Ayatollah Khomeini in a visit to Taleqani’s home.

Facing nationwide protests and doubtful of the military’s loyalty, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and his wife Farah fled Iran on January 16, 1979. A day before the Shah’s departure, Khomeini, still exiled in Paris, called for Iranians to “bury this regime and voice their support for the Islamic Republic” by joining nationwide demonstrations on January 19th. The Society joined the march in Kakh Square, an important center of Tehran Jewish life at the time. They carried a banner with the name of their organization. “We had convinced Yedidia Shofet, Iran’s Chief Rabbi, to walk with us a few blocks,” Yashayaie remembers. Shofet’s presence encouraged other Jews watching from the sidelines to join them, and they all walked together to Enghelab Square, a central meeting place two kilometers away. Twenty-six years after the Shah’s return in 1953, Khomeini flew from Paris to Tehran on February 1, 1979.

In the following months, the Society obtained a permit to publish the newspaper Tamuz. Its manifesto outlined their twofold existence as both revolutionary and Jewish. The Society also meant to bridge a gap between their community and a revolution brought to their country through the authority of Shi’a Islam. Members were determined that Iranian Jews and Shi’a revolutionaries reach mutual recognition. That proved impossible after the abrupt arrest and execution of Jewish industrialist Habib Elghanian in May 1979. A new wave of Jewish emigration began.

The Society had declared its support for the revolution before and after Khomeini’s return. It had not gained recognition in the wider ranks of the revolution, however, nor had it been able to safeguard a prominent member of the community. To voice its apprehension, the Society decided to visit Khomeini in person. Through an acquaintance of Yashayaie’s at the Komiteh, the revolution’s first security organization, they were able to schedule a meeting with Khomeini’s religious office.

Yedidia Shofet spoke first, followed by two members of the Society, one being Yashayaie. They voiced their support for the revolution and emphasized the need to recognize the rights of minorities. Khomeini responded by making a blunt distinction between “Zionism,” which he described as tyrannical, and “Judaism,” the religion of Prophet Moses frequently invoked in the Qur’an, and as such, the way of God. This distinction, says Yashayaie, was paramount to Jewish life in post-revolutionary Iran, giving them a tool with which to contrast Iranian Jewry and Israel.

No matter what the leaders of the revolution said, Yashayaie and other politically active minorities were certain that constitutional recognition would define their lives in the new state. A 73-member constituent assembly, the Assembly of Experts of the Constitution, was tasked with writing the charter in August 1979. Jews, Christians and Zoroastrians, the religions recognized under the new leadership, could each send one representative to the Assembly. The Society vouched for the election of Aziz Daneshrad, its close confidante, who had spent years in jail under the Shah as a member of the central committee of Tudeh.

Article 13, outlining the rights of non-Muslims, became a key dispute at the outset of the Assembly: They may exercise their religious ceremonies within the limits of Islamic law. Minority representatives, Yashayaie says, were outraged by the limit. Daneshrad said it turned his position on the Assembly into that of the “Fiddler on the Roof.” Rostam Shahzadi, a lawyer and Zoroastrian representative, gave an anguished speech to the Assembly accusing it of looking at non-Muslims as kafer, infidels. Ayatollah Beheshti, the vice-chair of the Assembly, held Daneshrad in high regard as a legal expert, Yashayaie says, and this helped minority representatives reach out to other members. The Assembly agreed to omit the word Islamic from the article, which still stands today as “They may exercise their religious ceremonies within the limits of the law.”

While Daneshrad worked inside the Assembly, Yashayaie advocated for Jewish rights by meeting with influential revolutionaries, including Khomeini himself on two more occasions. On November 18, 1982, Jewish representatives met with Khomeini in Tehran, along with groups from the Armenian, Assyrian and Zoroastrian communities, in an event titled “Synchronicity of Monotheistic Faiths.”

Yashayaie remembers entering the large, barren hall where Khomeini received visitors. The pasdars, members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, were sitting in the first rows near the podium. As the Jewish group entered, Yashayaie recalls, the pasdars began chanting “Marg bar Israel”—death to Israel. “We stepped out and I went to knock on Ayatollah Tavassoli’s door,” Yashayaie said. Tavassoli was Khomeini’s chief of staff, and Yashayaie communicated with him often. “We’ve come here to show our solidarity with the Imam, I told him. Why are the pasdars shouting ‘death to Israel’ with their fists in the air? If we are upsetting anyone, we will go home.” Tavassoli told them to wait while he spoke to Khomeini. He did not return, but a short while later Yashayaie saw the pasdars leaving through the front door. His group reentered the building, this time with no disturbance.

●

Yashayaie’s post-revolutionary life has been divided between public service, writing and film. He was voted president of the Tehran Jewish Committee, an unpaid position, in 1987. By that time, he says, the Jewish community had a greater appreciation for what the Society had tried to do: usher it into a new era, an Iran governed by a revolutionary Shi’a state.

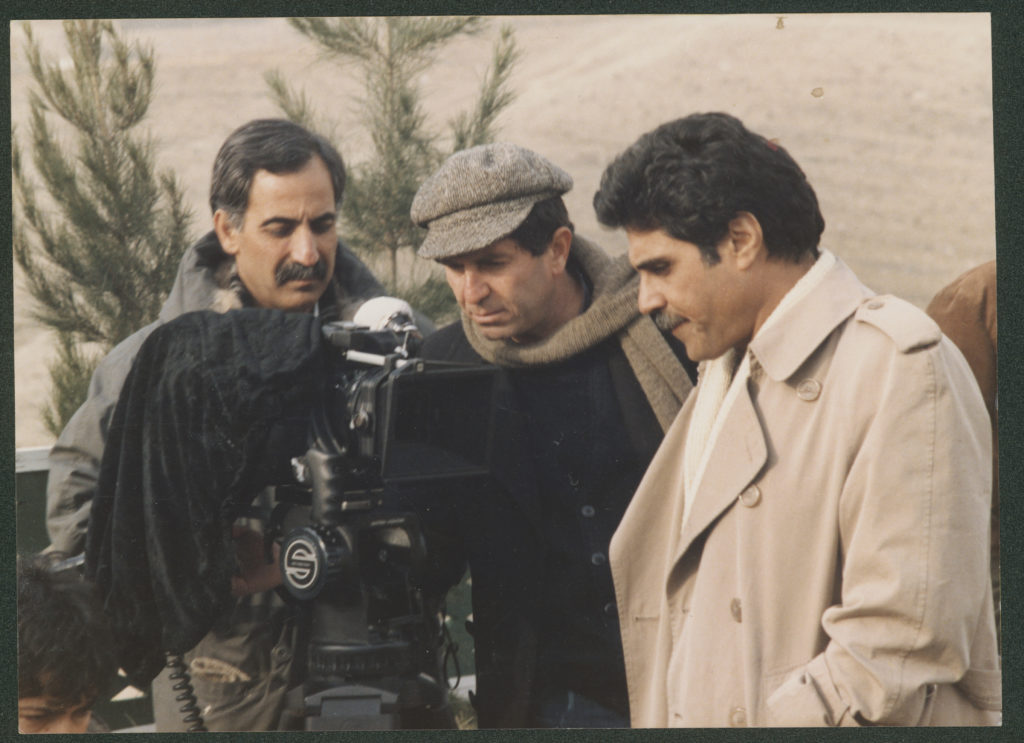

While working to maintain the Jewish administration of Jewish public schools, which were facing dwindling numbers, and to keep Jewish landmarks and buildings in Jewish hands, Yashayaie also became a groundbreaking movie producer. He and Jazani had long been involved in film, and at TabliFilm Abbas Kiarostami, Ali Hatami and Nasser Taghvai were among their early collaborators—artists who would later be known as members of Iran’s New Wave, weaving poetic symbolism into explorations of a people facing the chasms of their changing societies. TabliFilm was closed by orders of SAVAK after Jazani’s last arrest in 1968, and subsequently relaunched as Pakhshiran. When the revolution took place, Yashayaie had an extensive analog film laboratory at his disposal, and he decided to reposition Pakhshiran as a production company.

In 1982 he produced his first film, Jayezeh (“The Prize”), starring the Iranian-Armenian actress Irene Zazians. By the time the film was in post-production, the veil had become compulsory, which meant that Zazians’s many uncovered scenes would not be screened. Yashayaie rejected a proposal that the scenes be reshot, and the film was shelved. Pakhshiran’s next project was the comedy Ejareh Neshinha (“The Tenants”), released in 1986. Neighbors in a Tehran apartment building fight among themselves when the structure’s deteriorating plumbing causes major leaks, which ultimately lead the building to collapse. Some outraged revolutionaries claimed that the collapse was a metaphor for the revolution, or Iran, but the film became a critical and commercial success, even if Mohsen Makhmalbaf, a militant activist and filmmaker, called Yashayaie one day at the office to say he would “have to wear a grenade and blow up the theaters where it was shown.”

Makhmalbaf did not carry out his threat. Instead, he gained a reputation as a former revolutionary transformed into an award-winning New Wave artist, and in 1996 he and Yashayaie worked together on Nun o Goldoon (“Bread and Flowers”), a highly personal reflection on Makhmalbaf’s use of violence as a young revolutionary. In all, Pakhshiran produced ten films, most now considered classics, exploring issues such as the role of intellectuals in a post-revolutionary era, nationalism and the Iran-Iraq War.

Despite its commercial and critical success, Yashayaie closed Pakhshiran in 2006, right as he was resigning from his public roles in the community. Cinema was changing, he told me, becoming more “commercial,” and he also began to feel the work taking its physical toll. So he took on writing full time, for newspapers and literary magazines and book projects. His articles span a wide range of issues, including minority rights, his upbringing in Oudlajan and geopolitics in the Middle East. “I will take every opportunity to remind Iran and the world that Netanyahu does not speak for all Jews,” he says.

●

What remains of Jewish life in Oudlajan today—a number of synagogues and a public bath adorned with rich wall carvings and intricate mirror work—exists mostly as destinations for walking tours. Yashayaie and a group of a dozen Jewish men who were born in the neighborhood still drive there every Shabbat morning to worship. Journalists and tour guides often ask Yashayaie whether they can see a Shabbat service, and when I make the same request he sticks to the script and invites me to Ezra Yaghoub Synagogue, the oldest that still survives in Oudlajan.

Muslims and Zoroastrians also lived in the Oudlajan of Haroun Yashayaie’s childhood, known as a Jewish neighborhood. Relationships were mostly cordial, defined by distance and respect, he says. On Shabbat, Muslim neighbors would turn on the lights of the synagogue. His brother helped Muslim neighbors cook nazri—food made for public distribution during Ashura, when the Shi’a mourn the death of Hussein ibn Ali, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad.

Yashayaie remembers watching Ashura passion plays from the rooftop and can still recite the lament songs, having performed as Hussein’s warrior son, Ali al-Akbar. From his teenage years onwards, Yashayaie saw residents of Oudlajan move abroad or disperse into other parts of a rapidly growing metropolis. He is the ambassador of a Jewish community rooted in an old Tehran that no longer exists.

Today, small repair and storage shops serving the Tehran Grand Bazaar nearby have overtaken the neighborhood. But in a very narrow alley there is a metal door with two vertical rows of Stars of David that are at once a tribute to and a piece of the old Oudlajan. I ring the bell, and within a few minutes Yashayaie opens the door. He wears a yarmulke made of brown suede. Pointing to the path leading inside the synagogue, he tells me that his bar mitzvah was held here: “If I close my eyes, I can remember the sound of our steps, my friends and I, as we ran here pushing the flower arrangement on a trolley.” Mahyar, his twelve-year-old grandson, is with him to learn more about Shabbat rituals, in time for his own bar mitzvah.

As we walk inside, Yashayaie explains that the previous week there were only nine adult men, meaning that they did not have a minyan: only in the presence of ten men can they bring out the Torah. “You came on a good week,” he reassures me. He points for me to sit on one of the benches in the small, oak-paneled hall filled with stacks of books. Framed paintings of Abraham and Aaron, with long flowing white hair and beards, hang above the shelves.

After the service, I join Yashayaie on his drive to Bukhara’s office. A man named Sedq from the synagogue comes along; he is going to his mother’s home nearby. He is full-figured, with a round face and jolly, tired eyes. When I ask him why he still comes to Oudlajan every Saturday, he says, “When we open the doors of the synagogue, it’s like returning home.”

●

Though he is technically retired, Yashayaie occasionally takes on films in which he has a personal stake. Last year, he agreed to produce a documentary about Gholamreza Takhti. The only Iranian athlete to be nicknamed Jahan Pahlavan (the Champion of the World), Takhti was an Olympic gold-medal wrestler, but to men of Yashayaie’s generation he was considered a personal and political hero.

Takhti had been a supporter of Mossadeq, opposed to the Shah and SAVAK and personally involved in the lives of the poor, a dedication best exemplified by his work for the victims of the 1962 Boien Zahra earthquake. The pressure he endured at the hands of the Shah’s security forces and his early death at the age of 37 cemented his place as a national icon. Yashayaie was personally connected to the project in other ways: his brother, a wrestler, was friends with Takhti, and Bijan Jazani had been imprisoned for organizing a mass march on the day of Takhti’s memorial in 1968. (He remained in prison until his sudden execution in 1975.)

The Takhti film, Lionheart, premiered in 2018 at a ceremony at the National Museum of Iran followed by a tribute to Yashayaie’s “lifetime of dedication to the arts.” The screenwriter Farhad Tohidi was first to speak, praising Yashayaie as someone “who had long walked on the borders of Iran’s national movements.” Among his many contributions, said Tohidi, was reigniting Iranian cinema after the revolution. He was a nationally acclaimed figure in the way Takhti had been, his entire history interwoven with that of modern Iran.

Yashayaie considers Mossadeq as the archetype of a chehreyeh melli, a national figure, but he also believes that category includes Jazani and Takhti, as well as the mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani, the only woman to win a Fields Medal. Yashayaie may well join them. Three weeks after the tribute at the National Museum, he unveiled his new book of short stories at an event hosted by Bukhara. “I stood alongside people who gave their life for Iran, with no expectations,” he told the audience, referring to Jazani and other Fadaian friends. “I am proud to wear their name.” The movement to nationalize Iran’s oil and the revolutionary path that followed were all distinctly Iranian, free of ethnic or religious labels. And Yashayaie was always there, even if not at the very front of the line.

For Yashayaie, Iran is a shared history within the loose bounds of geography, long home to a multiplicity of religious communities, including Jews. But he also believes that Shiism is a pattern woven deep into the Iranian tapestry. Through his early life with Shi’a neighbors in Oudlajan, Yashayaie was to intuitively understand the eventual path of the revolutionary movement. That in turn enabled him to remain active politically and artistically in post-revolutionary Iran. In 1982 he gave a speech at the Tehran Friday Prayer on Quds Day. He is still the only non-Muslim to do so.

But how does he weigh what Iran has become against his youthful goals for a more free and fair society? “The revolution was a step toward more political participation, and independence—but that doesn’t mean it came without its own remorse or that our list of aspirations were achieved,” he tells me. When I refer to forced hijab as an encroachment on the rights of women after the revolution, he shrugs it off, pointing to the advancement of women in academia, the arts and sports after 1979. The alternative was staying home, he believes. Having witnessed social unrest for the greater part of his eighty years, he has a loose doctrine of tolerating prejudice so long as one can devise ways to outmaneuver it.

“We live in a very volatile part of the world where a weakened state is immediately exploited by outside powers,” he says, the eight-year war between Iran and Iraq serving as a critical example. He stresses that “wisdom” must be applied in the expression of discontent, because Iranians face the double challenge of trying to instill change in the system “while keeping its integrity.” He who once marched for revolution now believes that even waiting can be transformative, sowing seeds slowly without knowing if they will take root. He goes so far as to call this act of waiting revolutionary, rendering the word either meaningless or rife with new possibility. “You must remember this,” he says. “Inna allaha ma as-sabireen.” He quotes Ayah 153 from the second Surah of the Qur’an, Al Baqarah, in which God admonishes the Israelites but also calls them his chosen people: “Indeed, Allah is with the patient.”

Photographs courtesy of Haroun Yashayaie

In December 2005, in his fourth month as president of Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad called the Holocaust a myth. This was during an interview with Al-Alam, an Arabic-language channel broadcast from Tehran. The interview wasn’t an outlier. A year earlier, under new leadership, Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, the state-owned TV network that operates Al-Alam, broadcast a number of programs that described the Holocaust as a “made-up story,” a fiction or a myth. IRIB has always been hostile to what it calls the “Zionist Regime,” but prior to 2004 there had been no orchestrated campaign to cast the Holocaust as a lie.

Haroun Yashayaie is a past head of the Tehran Jewish Committee, an umbrella organization that oversees the administration of the city’s Jewish schools, kosher butcher shops and synagogues. A former film executive and newspaper editor, Yashayaie, who is 84, has always kept an eye on the media. When an IRIB channel labeled the Holocaust a fiction, he wrote an open letter in condemnation. When Ahmadinejad repeated the claim, he wrote another: “The Holocaust is, in fact, an open wound on the hands of Western civilization. … The Holocaust is not a myth in the same way that the massacre at Sabra and Shatila is not a myth.” After distributing the second letter to the media, Yashayaie personally delivered it to Ahmadinejad at a summit for religious minorities. The new president and his key cultural advisers were conflating criticisms of Israel with Holocaust denial, Yashayaie contended, and thereby whitewashing the crimes of fascism.

In both letters, Yashayaie emphasized that he had never been shy of publicly criticizing Israel. As a graduate student at the University of Tehran in 1967, he was one of the few students to speak out against the Six-Day War, publishing an open letter in Ferdowsi magazine titled “As a Jew I Am Ashamed.” At the time Iran and Israel were staunch allies, and in retaliation for his letter, Yashayaie says, he was summarily arrested and imprisoned by the Shah’s security forces. He protested that the rhetoric he had condemned concerned not Israel but rather “an ablution of neo-fascism.”

During his nineteen years as president of the Tehran Jewish Committee, Yashayaie met two of Ahmadinejad’s predecessors, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (1989-97) and Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005). He visited Rafsanjani on at least two occasions, and was received with open arms. “Rafsanjani was the most nonchalant cleric I ever met,” he says. Khatami attended a synagogue service in February 2004 at the invitation of the Jewish Committee, a “milestone” in Jewish relations with the Islamic Republic, according to Yashayaie.

Now retired, Yashayaie can still be found most days at his production company, Pakhshiran, on the sixth floor of what was once a white marble building in downtown Tehran, now soot-gray and surrounded by stores selling baby goods. This is where I visit Yashayaie weekly, mostly on Sundays, a day after Shabbat, which he prefers. The vintage movie posters lining the hallway to Pakhshiran’s door tell stories of car chases, thieves and quarreling neighbors. Inside, visitors can quickly spot Yashayaie’s office. On one side is a bookshelf that holds the company’s film prizes, including the Bronze Leopard at Locarno, and also a keffiyeh and prayer beads from Iran’s Supreme Leader. On the other side, photos of decaying landscapes frame the wall, recalling Iran of an earlier Persian era, when Yashayaie was born.

“I learned early on that the best way to address discrimination is out loud,” Yashayaie said when I first asked about his open letters on the Holocaust. He was referring to his student days in the Fifties at the French Jewish Alliance Française boys’ high school. Within walking distance was the headquarters of Iran’s national socialist party, SUMKA, founded by Davud Monshizadeh, a Nazi sympathizer who had lived and studied in Germany during the Third Reich. The SUMKA wore black shirts and armbands with a birdlike figure resembling a swastika. Barely numbering into the hundreds, they were known for attacking members of the Tudeh (Masses), Iran’s communist party. They also taunted Jewish girls, whose school was adjacent to the SUMKA office, by shouting anti-Semitic slurs as the students walked home.

“So,” Yashayaie said, “I joined the communist students from a nearby high school who came to fight the SUMKA.” He was eventually expelled from the Alliance for “hooliganism”—skirmishes with the SUMKA. Across those years and the more than fifty years that followed, Yashayaie would see the rise and fall of a national movement led by Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq, learn from the morning paper that his closest friends, prominent Marxists, had been executed in prison and lead one of Iran’s most successful advertising and movie production firms. With hundreds of others, he stood at the steps of the Air France plane that brought Ayatollah Khomeini to Tehran from Paris in 1979, a bouquet of flowers in his hands, declaring solidarity with the Revolution. A decade later he produced Hamoun, a film that elaborately explores an intellectual’s existential anxieties in a post-revolutionary age.

For someone like me, a post-1979 Iranian, Yashayaie represents a revolutionary movement that was open to membership across religious and political affiliations, and while opposing imperialist ambitions at home could still leave itself exposed to a questioning world. He is an embodiment of the diversity that made the transition of power in 1979 possible.

Near the end of many of our weekly conversations, I ask Yashayaie variations of the same question: How can one hold revolutionary idealism, the belief that collective action can lead to the betterment of society, to such lofty concepts as “equality” and “justice,” when the movement’s romanticism has long fizzled out? As he listens he holds a sugar cube between his teeth and sips tea loudly, a talent unique to men of the old teahouses.

“God created the world in six days, supposedly, and we are still trying to make it better,” he replied once, before taking down the Book of Genesis from his library and reading its depiction of the Fall. “Because man is inherently flawed—and will always be seeking change,” he proclaimed, his head of thick, wavy white hair as smooth and resilient as freshly piled snow on a rooftop. Every generation can find a place to seek improvement over the status quo, he insists. “The question is the decisions you will make if and when you find yourself in that place.”

●

Yashayaie regularly visits the office of the monthly literary magazine Bukhara to drop off manuscripts and have contentious conversations with Ali Dehbashi, Bukhara’s editor and his friend of thirty years. Usually their arguments end with Yashayaie yelling “salawat befrest!” (send peace upon Prophet Muhammad), calling for Dehbashi to calm down.

On this particular day we sit amid paper piles arranged on the floor like fortifications. Pen and paper in hand, Yashayaie draws a map of his childhood domain. Tehran’s Jewish Quarter, Oudlajan, where he lived, and Iran’s parliament in Baharestan Square have already been identified, as well as the street connecting them, which he walked at least twice a day. “It was the geography of my home that opened a window into Iran’s most turbulent years,” he says. He points to the location of Alliance, the girls’ school and the SUMKA headquarters all clustered near Baharestan Square.

“Baharestan is where he caught communism,” snorts Dehbashi, looking up from an article. A hardline newspaper has published a report calling him a freemason again—a baseless accusation that always makes a future publication ban more likely. Deshbashi hollers: “This is the legacy of the communists in Iran—they taught everyone how to carry out character assassination!”

Among the communist students Yashayaie met during his after-school fights with the SUMKA was his future business partner, Bijan Jazani, who was a leader of the Tudeh Party’s Youth Organization. Yashayaie was never formally a member of Tudeh, but he has long identified as a communist. He joined Jazani and other Tudeh youth in handing out the organization’s student newspaper and backing Mohammad Mossadeq’s Nationalist Front, a broad coalition of political organizations that supported Mossadeq’s call to independence.

When an oil nationalization bill was passed by parliament on March 15, 1951, and Mossadeq, a Swiss-educated law professor who was elected to parliament on a platform to bring Iran’s oil fields under public control, was elected prime minister the following month, Iran was euphoric. “Dr. Mossadeq’s charisma brought out a sense of national solidarity among all of us,” Yashayaie says. “We thought we could do anything—even face world powers.”

Both Britain and the United States were adamantly opposed to Mossadeq, fearing that his nationalization project would jeopardize their favorable oil concessions. Despite official negotiations with Mossadeq’s government, the British privately made clear to the U.S. that they would never agree to cede control of the flow of Iranian oil. When Mossadeq refused to capitulate, the British cabinet led an international embargo on Iran’s oil, the government’s primary source of income, and froze Iranian assets.

The ensuing economic turmoil did not remove Mossadeq from power, as the Americans and British had hoped, so they settled on a scheme privately backed by Iran’s monarch, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah, to overthrow him in a coup d’état. In the months leading up to the operation, various opposition groups, including the SUMKA party, were paid by the CIA to publish propaganda and stir up opposition to the government.

The operation was initially carried out on August 15, 1953, without success. Details had been leaked to Mossadeq through informants in the military, and he had put his chief of staff on alert. The Shah and his wife fled to Baghdad and then to Rome on a private plane. But the armed forces, aided and abetted by the CIA, turned the tide. By mid-afternoon on August 18th, with bands of looters and coordinated rioters ransacking shops, smashing windows and lighting fires at every street corner, army commanders drove their tanks into the city, and eventually toward Mossadeq’s home. Yashayaie, along with Jazani and other friends, was at Darvazeh Dowlat all day, one of old Tehran’s main gates a mile away from Baharestan. They were waiting for orders to “go to war,” he says—to attack coup supporters. The orders never came.

By late afternoon, Mossadeq had surrendered, and many in his administration had been taken into custody. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi returned to assume power. From the point of view of Yashayaie and the young communists, the monarch had returned to sit on a throne fully upholstered by imperialist powers. “The seed of the revolution was planted at that moment,” Yashayaie says. Mossadeq would be put under house arrest until his death in 1967. His fall was a fatal blow to the possibility of an Iranian path to a more democratic political process.

Among the Tudeh sympathizers who were arrested en masse after the coup, Jazani and Yashayaie were confined to Tehran’s Qasr prison. Within weeks of being released, however, both sat for the entrance exam for the University of Tehran’s philosophy department. Both were admitted. They also launched a company called Persepolis, Tehran’s first movie-advertising firm, serving the country’s nascent film industry. Jazani, an illustrator, designed advertisements that were photographed on film slides to be shown in theaters. Yashayaie and Jazani’s uncle distributed the slides to movie houses across Tehran that had never before screened ads.

While Yashayaie poured most of his energy into their business, Jazani, who had been raising a family since the time he was 25, had gone from being a high school youth organizer to a leading figure within the student movement at the University of Tehran. A generation of educated young people, the first in their family to attend university, joined guerrilla movements formed after the 1953 coup. Nearly four hundred were allegedly killed by SAVAK, the Iranian Intelligence and Security Organization established in 1957 with the help of the CIA.

By 1968, when he was imprisoned for the last time, Jazani was calling for armed resistance against the Shah. He had secretly co-founded a Marxist organization that had maintained enough recruits outside prison to remain operational, and in 1971 Jazani and the recruits joined another Marxist assembly to launch the Iranian People’s Fadaian Guerrillas. Jazani is widely considered the intellectual father of Fadaian, with many of his treatises, including The Thirty-Year History of Iran, distributed among young guerrillas, but he was executed overnight in 1975. The day Yashayaie saw news of Jazani’s death in the paper was “the absolute worst day of my life,” he recalls. It was claimed that Jazani and six other Fadaian, as well as two guerrillas from another militant group, were shot while trying to flee, but Yashayaie says he knew that was a lie—they were put before a firing squad.

Today, Yashayaie is often called upon as a witness and a footnote to the rise of leftist militancy in post-coup Iran. When I ask him how privy he was to Jazani’s relationship to the Fadaian, Yashayaie is coy, saying he and Jazani were best friends and business partners but that he “kept out” of Jazani’s politics. Instead he devoted himself to their company, which had by then expanded greatly to employ nearly three hundred people and changed its name to TabliFilm: “I told Bijan that even if you want to die, a burial requires cash, so I stuck to the business.” But TabliFilm’s large Tehran office turned into a hub for both leftist activists and artists, and was raided and eventually taken over by SAVAK.

As the media leads a new onslaught on the left and his fallen friends, Yashayaie has emerged as their defender, a mission for him as urgent as confronting Holocaust denial. “These were good kids in impossible circumstances. We can criticize their use of violence but the backdrop matters.” Privately, he points out how demeaning media coverage has only helped to boost the popularity of the old left in Iran and broaden the notion of what it had meant to be a revolutionary before the victory of the Islamic Revolution in 1979. For example, in May 2015, Mehrnameh, a monthly magazine of culture and politics, ran a disparaging profile of Jazani. On the cover, Jazani, painted in acrylic, looks straight ahead with a satisfied smirk. A blue hue outlines his body, and above his head it takes the shape of a gun. The phrase “The Terrorist Intellectuals” hovers in large letters by his shoulder. Magazines run covers with Jazani’s face on them because, no matter what they say about him, they know that it will sell. The very effort to condemn the left has etched it back into the grand collage of the revolution.

●

By 1975, the year of Jazani’s death, the Fadaian had taken note of the rise of the charismatic cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Other opposition groups had failed in taking direct aim at the Shah, Jazani argued, but that was precisely what Khomeini was doing. A marja, a Shi’a cleric of the highest religious authority, Khomeini became a widely known figure in 1963 after attacking the Shah’s political and land reforms. With Khomeini’s arrest, protests broke out in Tehran, where hundreds were reported to have been killed by the military. Yashayaie, who was on the streets with other university students during the demonstrations, remembers it as a major turning point in cementing Khomeini’s political prominence. Though clerics joined the tide of the anti-Shah protests, Yashayaie was still committed to what was then a nationwide movement. The challenges of a revolutionary Jew after the victory of an Islamic revolution would come later. “When the revolution finally came it was like a wave, you had to flow through,” he says.

Within a year, Khomeini, who had been released from prison, attacked the government for approving the “capitulation law,” which granted legal impunity to American military personnel stationed in Iran. “We are less than American dogs,” Khomeini said in a harshly worded speech. “To Allah, he is guilty of great sin who does not scream. … Is not our country under American occupation?” Khomeini was arrested and exiled first to Bursa, Turkey, and then for twelve years to Najaf, Iraq. As Khomeini was already a prominent marja, his exile only broadened his reach.

Among a new generation of student activists in Iran and abroad, Shi’a liberation ideology, inspired by both Shiism and anti-colonial struggles across the world, was gaining traction. Dissident clerics in confrontation with the Shah’s regime, like Mahmoud Taleqani, were galvanizing a movement that was strongly imbued with the language of Shi’a theology. Taleqani was a founder of the Freedom Movement of Iran, an offshoot of Mossadeq’s National Front, and a confidante of Khomeini’s. Taleqani and members of the Organization of Jewish Students, a left-leaning Jewish student body at the University of Tehran, of which Yashayaie was a founding member, had become acquainted while serving sentences in Tehran’s Qasr Prison.

In the summer of 1978, as anti-Shah protests were rapidly growing, Yashayaie was working with the board of directors at the Dr. Sapir Jewish Hospital. When riots broke out, injured protesters sought refuge there. As the Shah’s fall seemed imminent, Yashayaie and a group of eleven activists from the former Organization of Jewish Students, who now called themselves the Society of Jewish Intellectuals, declared their solidarity with Ayatollah Khomeini in a visit to Taleqani’s home.

Facing nationwide protests and doubtful of the military’s loyalty, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and his wife Farah fled Iran on January 16, 1979. A day before the Shah’s departure, Khomeini, still exiled in Paris, called for Iranians to “bury this regime and voice their support for the Islamic Republic” by joining nationwide demonstrations on January 19th. The Society joined the march in Kakh Square, an important center of Tehran Jewish life at the time. They carried a banner with the name of their organization. “We had convinced Yedidia Shofet, Iran’s Chief Rabbi, to walk with us a few blocks,” Yashayaie remembers. Shofet’s presence encouraged other Jews watching from the sidelines to join them, and they all walked together to Enghelab Square, a central meeting place two kilometers away. Twenty-six years after the Shah’s return in 1953, Khomeini flew from Paris to Tehran on February 1, 1979.

In the following months, the Society obtained a permit to publish the newspaper Tamuz. Its manifesto outlined their twofold existence as both revolutionary and Jewish. The Society also meant to bridge a gap between their community and a revolution brought to their country through the authority of Shi’a Islam. Members were determined that Iranian Jews and Shi’a revolutionaries reach mutual recognition. That proved impossible after the abrupt arrest and execution of Jewish industrialist Habib Elghanian in May 1979. A new wave of Jewish emigration began.

The Society had declared its support for the revolution before and after Khomeini’s return. It had not gained recognition in the wider ranks of the revolution, however, nor had it been able to safeguard a prominent member of the community. To voice its apprehension, the Society decided to visit Khomeini in person. Through an acquaintance of Yashayaie’s at the Komiteh, the revolution’s first security organization, they were able to schedule a meeting with Khomeini’s religious office.

Yedidia Shofet spoke first, followed by two members of the Society, one being Yashayaie. They voiced their support for the revolution and emphasized the need to recognize the rights of minorities. Khomeini responded by making a blunt distinction between “Zionism,” which he described as tyrannical, and “Judaism,” the religion of Prophet Moses frequently invoked in the Qur’an, and as such, the way of God. This distinction, says Yashayaie, was paramount to Jewish life in post-revolutionary Iran, giving them a tool with which to contrast Iranian Jewry and Israel.

No matter what the leaders of the revolution said, Yashayaie and other politically active minorities were certain that constitutional recognition would define their lives in the new state. A 73-member constituent assembly, the Assembly of Experts of the Constitution, was tasked with writing the charter in August 1979. Jews, Christians and Zoroastrians, the religions recognized under the new leadership, could each send one representative to the Assembly. The Society vouched for the election of Aziz Daneshrad, its close confidante, who had spent years in jail under the Shah as a member of the central committee of Tudeh.

Article 13, outlining the rights of non-Muslims, became a key dispute at the outset of the Assembly: They may exercise their religious ceremonies within the limits of Islamic law. Minority representatives, Yashayaie says, were outraged by the limit. Daneshrad said it turned his position on the Assembly into that of the “Fiddler on the Roof.” Rostam Shahzadi, a lawyer and Zoroastrian representative, gave an anguished speech to the Assembly accusing it of looking at non-Muslims as kafer, infidels. Ayatollah Beheshti, the vice-chair of the Assembly, held Daneshrad in high regard as a legal expert, Yashayaie says, and this helped minority representatives reach out to other members. The Assembly agreed to omit the word Islamic from the article, which still stands today as “They may exercise their religious ceremonies within the limits of the law.”

While Daneshrad worked inside the Assembly, Yashayaie advocated for Jewish rights by meeting with influential revolutionaries, including Khomeini himself on two more occasions. On November 18, 1982, Jewish representatives met with Khomeini in Tehran, along with groups from the Armenian, Assyrian and Zoroastrian communities, in an event titled “Synchronicity of Monotheistic Faiths.”

Yashayaie remembers entering the large, barren hall where Khomeini received visitors. The pasdars, members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, were sitting in the first rows near the podium. As the Jewish group entered, Yashayaie recalls, the pasdars began chanting “Marg bar Israel”—death to Israel. “We stepped out and I went to knock on Ayatollah Tavassoli’s door,” Yashayaie said. Tavassoli was Khomeini’s chief of staff, and Yashayaie communicated with him often. “We’ve come here to show our solidarity with the Imam, I told him. Why are the pasdars shouting ‘death to Israel’ with their fists in the air? If we are upsetting anyone, we will go home.” Tavassoli told them to wait while he spoke to Khomeini. He did not return, but a short while later Yashayaie saw the pasdars leaving through the front door. His group reentered the building, this time with no disturbance.

●

Yashayaie’s post-revolutionary life has been divided between public service, writing and film. He was voted president of the Tehran Jewish Committee, an unpaid position, in 1987. By that time, he says, the Jewish community had a greater appreciation for what the Society had tried to do: usher it into a new era, an Iran governed by a revolutionary Shi’a state.

While working to maintain the Jewish administration of Jewish public schools, which were facing dwindling numbers, and to keep Jewish landmarks and buildings in Jewish hands, Yashayaie also became a groundbreaking movie producer. He and Jazani had long been involved in film, and at TabliFilm Abbas Kiarostami, Ali Hatami and Nasser Taghvai were among their early collaborators—artists who would later be known as members of Iran’s New Wave, weaving poetic symbolism into explorations of a people facing the chasms of their changing societies. TabliFilm was closed by orders of SAVAK after Jazani’s last arrest in 1968, and subsequently relaunched as Pakhshiran. When the revolution took place, Yashayaie had an extensive analog film laboratory at his disposal, and he decided to reposition Pakhshiran as a production company.

In 1982 he produced his first film, Jayezeh (“The Prize”), starring the Iranian-Armenian actress Irene Zazians. By the time the film was in post-production, the veil had become compulsory, which meant that Zazians’s many uncovered scenes would not be screened. Yashayaie rejected a proposal that the scenes be reshot, and the film was shelved. Pakhshiran’s next project was the comedy Ejareh Neshinha (“The Tenants”), released in 1986. Neighbors in a Tehran apartment building fight among themselves when the structure’s deteriorating plumbing causes major leaks, which ultimately lead the building to collapse. Some outraged revolutionaries claimed that the collapse was a metaphor for the revolution, or Iran, but the film became a critical and commercial success, even if Mohsen Makhmalbaf, a militant activist and filmmaker, called Yashayaie one day at the office to say he would “have to wear a grenade and blow up the theaters where it was shown.”

Makhmalbaf did not carry out his threat. Instead, he gained a reputation as a former revolutionary transformed into an award-winning New Wave artist, and in 1996 he and Yashayaie worked together on Nun o Goldoon (“Bread and Flowers”), a highly personal reflection on Makhmalbaf’s use of violence as a young revolutionary. In all, Pakhshiran produced ten films, most now considered classics, exploring issues such as the role of intellectuals in a post-revolutionary era, nationalism and the Iran-Iraq War.

Despite its commercial and critical success, Yashayaie closed Pakhshiran in 2006, right as he was resigning from his public roles in the community. Cinema was changing, he told me, becoming more “commercial,” and he also began to feel the work taking its physical toll. So he took on writing full time, for newspapers and literary magazines and book projects. His articles span a wide range of issues, including minority rights, his upbringing in Oudlajan and geopolitics in the Middle East. “I will take every opportunity to remind Iran and the world that Netanyahu does not speak for all Jews,” he says.

●

What remains of Jewish life in Oudlajan today—a number of synagogues and a public bath adorned with rich wall carvings and intricate mirror work—exists mostly as destinations for walking tours. Yashayaie and a group of a dozen Jewish men who were born in the neighborhood still drive there every Shabbat morning to worship. Journalists and tour guides often ask Yashayaie whether they can see a Shabbat service, and when I make the same request he sticks to the script and invites me to Ezra Yaghoub Synagogue, the oldest that still survives in Oudlajan.

Muslims and Zoroastrians also lived in the Oudlajan of Haroun Yashayaie’s childhood, known as a Jewish neighborhood. Relationships were mostly cordial, defined by distance and respect, he says. On Shabbat, Muslim neighbors would turn on the lights of the synagogue. His brother helped Muslim neighbors cook nazri—food made for public distribution during Ashura, when the Shi’a mourn the death of Hussein ibn Ali, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad.

Yashayaie remembers watching Ashura passion plays from the rooftop and can still recite the lament songs, having performed as Hussein’s warrior son, Ali al-Akbar. From his teenage years onwards, Yashayaie saw residents of Oudlajan move abroad or disperse into other parts of a rapidly growing metropolis. He is the ambassador of a Jewish community rooted in an old Tehran that no longer exists.

Today, small repair and storage shops serving the Tehran Grand Bazaar nearby have overtaken the neighborhood. But in a very narrow alley there is a metal door with two vertical rows of Stars of David that are at once a tribute to and a piece of the old Oudlajan. I ring the bell, and within a few minutes Yashayaie opens the door. He wears a yarmulke made of brown suede. Pointing to the path leading inside the synagogue, he tells me that his bar mitzvah was held here: “If I close my eyes, I can remember the sound of our steps, my friends and I, as we ran here pushing the flower arrangement on a trolley.” Mahyar, his twelve-year-old grandson, is with him to learn more about Shabbat rituals, in time for his own bar mitzvah.

As we walk inside, Yashayaie explains that the previous week there were only nine adult men, meaning that they did not have a minyan: only in the presence of ten men can they bring out the Torah. “You came on a good week,” he reassures me. He points for me to sit on one of the benches in the small, oak-paneled hall filled with stacks of books. Framed paintings of Abraham and Aaron, with long flowing white hair and beards, hang above the shelves.

After the service, I join Yashayaie on his drive to Bukhara’s office. A man named Sedq from the synagogue comes along; he is going to his mother’s home nearby. He is full-figured, with a round face and jolly, tired eyes. When I ask him why he still comes to Oudlajan every Saturday, he says, “When we open the doors of the synagogue, it’s like returning home.”

●

Though he is technically retired, Yashayaie occasionally takes on films in which he has a personal stake. Last year, he agreed to produce a documentary about Gholamreza Takhti. The only Iranian athlete to be nicknamed Jahan Pahlavan (the Champion of the World), Takhti was an Olympic gold-medal wrestler, but to men of Yashayaie’s generation he was considered a personal and political hero.

Takhti had been a supporter of Mossadeq, opposed to the Shah and SAVAK and personally involved in the lives of the poor, a dedication best exemplified by his work for the victims of the 1962 Boien Zahra earthquake. The pressure he endured at the hands of the Shah’s security forces and his early death at the age of 37 cemented his place as a national icon. Yashayaie was personally connected to the project in other ways: his brother, a wrestler, was friends with Takhti, and Bijan Jazani had been imprisoned for organizing a mass march on the day of Takhti’s memorial in 1968. (He remained in prison until his sudden execution in 1975.)

The Takhti film, Lionheart, premiered in 2018 at a ceremony at the National Museum of Iran followed by a tribute to Yashayaie’s “lifetime of dedication to the arts.” The screenwriter Farhad Tohidi was first to speak, praising Yashayaie as someone “who had long walked on the borders of Iran’s national movements.” Among his many contributions, said Tohidi, was reigniting Iranian cinema after the revolution. He was a nationally acclaimed figure in the way Takhti had been, his entire history interwoven with that of modern Iran.

Yashayaie considers Mossadeq as the archetype of a chehreyeh melli, a national figure, but he also believes that category includes Jazani and Takhti, as well as the mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani, the only woman to win a Fields Medal. Yashayaie may well join them. Three weeks after the tribute at the National Museum, he unveiled his new book of short stories at an event hosted by Bukhara. “I stood alongside people who gave their life for Iran, with no expectations,” he told the audience, referring to Jazani and other Fadaian friends. “I am proud to wear their name.” The movement to nationalize Iran’s oil and the revolutionary path that followed were all distinctly Iranian, free of ethnic or religious labels. And Yashayaie was always there, even if not at the very front of the line.

For Yashayaie, Iran is a shared history within the loose bounds of geography, long home to a multiplicity of religious communities, including Jews. But he also believes that Shiism is a pattern woven deep into the Iranian tapestry. Through his early life with Shi’a neighbors in Oudlajan, Yashayaie was to intuitively understand the eventual path of the revolutionary movement. That in turn enabled him to remain active politically and artistically in post-revolutionary Iran. In 1982 he gave a speech at the Tehran Friday Prayer on Quds Day. He is still the only non-Muslim to do so.

But how does he weigh what Iran has become against his youthful goals for a more free and fair society? “The revolution was a step toward more political participation, and independence—but that doesn’t mean it came without its own remorse or that our list of aspirations were achieved,” he tells me. When I refer to forced hijab as an encroachment on the rights of women after the revolution, he shrugs it off, pointing to the advancement of women in academia, the arts and sports after 1979. The alternative was staying home, he believes. Having witnessed social unrest for the greater part of his eighty years, he has a loose doctrine of tolerating prejudice so long as one can devise ways to outmaneuver it.

“We live in a very volatile part of the world where a weakened state is immediately exploited by outside powers,” he says, the eight-year war between Iran and Iraq serving as a critical example. He stresses that “wisdom” must be applied in the expression of discontent, because Iranians face the double challenge of trying to instill change in the system “while keeping its integrity.” He who once marched for revolution now believes that even waiting can be transformative, sowing seeds slowly without knowing if they will take root. He goes so far as to call this act of waiting revolutionary, rendering the word either meaningless or rife with new possibility. “You must remember this,” he says. “Inna allaha ma as-sabireen.” He quotes Ayah 153 from the second Surah of the Qur’an, Al Baqarah, in which God admonishes the Israelites but also calls them his chosen people: “Indeed, Allah is with the patient.”

Photographs courtesy of Haroun Yashayaie

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.