I spent the day at an art museum and the night at a sex club. In the museum, I tugged the hem of my dress down to cover the tops of my thigh-high stockings every time I sat on a bench. In the club, I looked up from kissing strangers to identify reproductions of erotic paintings in gilt frames: Leda and the swan, Watteau’s mistress wallowing on a silk-covered bed, Galatea—her legs still cold marble—bending to embrace Pygmalion.

I was traveling in Paris. What a contrast, I’d thought as I prepared to leave the Louvre, putting on dark lipstick in an age-spotted mirror in a gallery of decorative arts. But I’ve been reconsidering. Is the pleasure I take in museums really so different from the pleasure I find in a sex club?

●

I imagine touching the bodies I see in art. That day at the Louvre, standing before an ancient statue of a Mesopotamian ruler, I’d wanted to bend and lick the polished darkness of its bald head. I imagined it warm and cool at the same time on my tongue, like flesh and stone mixed.

It’s not as though I’m masturbating behind the display cases. But my attention to the art has an erotic edge.

The first time I remember seeing this way was at a going-away party for my fifth-grade teacher. I was flipping through a catalog as I sat on the beige-carpeted steps of a sunken living room in a house up in the foothills of Tucson, Arizona, plumes of ocotillo cactus whipping in the wind outside.

This was in the mid-Nineties. I was enrolled in an evangelical Christian private school, and my teacher was leaving to become a missionary in China. I’d cross-stitched a pillow for her, embroidering it with a loop of pink and red flowers. Our mothers praised the teacher’s Christianity and murmured about the danger she would face. Preaching the gospel was somehow illegal, or barely tolerated, in China. We were told to be jealous of our teacher for having such a good opportunity to demonstrate her faith. She might even get to be a martyr—a direct ticket to heaven, with no worrying whatsoever about any sins she might have committed here on earth.

I loved my teacher. She was young and kind, with honeyed hair that curled at the tops of her shoulders. I didn’t want to think about her leaving, so I picked up a catalog from a stack on the end table beside me. Land’s End.

It opened to a full-length photograph of a model stepping out of the ocean, wearing a blue bathing suit with a skirt ruffled around her hips to hide cellulite she did not have. Her face was long and calm. Her honeyed hair slid down to curl at the tops of her bare shoulders.

I lost all awareness of the party, and even the room, as my attention sank into the image. The tiny triangle of blue that showed beneath her skirt, between her legs, expanded to fill my vision.

My hand moved to tear out the page. I wanted to fold it tenderly and carry it home. But then I came back to myself, remembering that I was in a room full of eyes. A classmate or a mother or even my teacher might ask what I was doing. How could I explain wanting a picture of a woman in a swimsuit?

I thought of tearing out just that triangle. A blue speck of paper couldn’t be suspicious. But what if someone saw me touching the woman there as I tore?

Instead, I memorized her. I can still see her calm face, accepting that I or anyone else might look at her body. But so well did I disguise my attraction—from my classmates, from the adults and especially from myself—that it’s only now, while writing this, that I’ve realized that the model looked like my teacher, and that I loved my teacher not just for her kindness, but for her beauty.

Later, on a high school field trip to the Tucson Museum of Art, I stood close to a monochromatic painting. It was my first time at a museum. My eyes unfocused. All I could hear was a buzz, growing louder as the canvas spread out to surround me. I was nothing but a pair of floating eyes.

My knees buckled and I fell sideways against a friend. “Sorry,” I said.

“What do you think of this one?” he asked.

“It’s okay,” I said.

It was the same blue.

●

I walked through the Metro station under the Louvre. A niche on the platform displayed a plaster reproduction of one of the most famous works in the museum, Michelangelo’s The Dying Slave. It’s a sculpture of a boy caressing himself, pushing up a band of cloth wrapped around his chest, his eyes closed and his hips thrust out. So many commuters had taken this as an invitation to touch that his cock was rubbed down to a blur.

Inside the museum, looking at the original, I sensed Michelangelo looking at his model appraisingly, desirously, and looking in the same way at the marble body he was carving.

If I looked at the museum guard standing in the gallery in the same way I was looking at the statue, everyone would know I wanted to touch him, smell him, balance my shins on his thighs as I pinned him under me. The guard would notice me looking at him. He might be aroused or he might be disgusted, but he would react. The other visitors would react, too, with amusement or encouragement or scorn.

But to look at a sculpted or painted body is to contemplate without blame. Looking at Michelangelo’s desire, my own remained hidden.

●

The sex club, on the Île-Saint-Louis, had free gummy bears. A big glass jar of them, with tongs for making your selection set on a little plate. My date and I handed over our bags and phones to the proprietress, who looked like a cheerful Simone Signoret in pearls and a twin set.

She asked for our names. I said Louise. My date, whom I’d met on an app the day before, laughed and called himself Louis.

Downstairs, the proprietress’s husband manned the bar. I ordered a gin and tonic. I like the way you say it in French, slurring the words into one, ginantonic, like you’re already drunk. Next to the bar was a dance floor flanked by low tables. Laser projections spun from the ceiling—sparkles and geometric shapes. Occasionally a herd of animated pigs materialized around the feet of whoever was giving the central stripper pole a whirl.

The patrons looked like guests at the tipsy end of a wedding. The men wore suits with discarded jackets, and the women dry-clean-only dresses of the kind that are sexy without scandalizing a bride’s mother. The one exception, a woman with a tangle of curls, was wearing a dress whose back dipped so low that I could see the wings of her lower-back tattoo flapping as she wiggled to the beat.

I slid my way down the banquette to talk to a couple I heard speaking English. “I don’t know if my French is up to this!” was my opening line.

“Neither do I!” the woman replied, although it turned out that she had been living in Paris for years. She was American and her husband, his eyes bulging with anxiety, was French. They said it was their first time doing anything like this. He looked like a soldier hoping to escape the coming battle with his honor intact, if not his life.

Louis, uninterested in them, tugged on my sleeve. I said goodbye and we went deeper into the club’s back rooms. A bathroom with a shower. A room with only one bed and a door with a large window. The farthest room held a number of padded benches occupied by couples.

Here, the cellar’s shaggy stone walls were left exposed. A device of crossed supports and straps stood in a corner for floggings. The whips were hanging behind the bar. You could ask the bartender to borrow them, like darts in a pub.

As Louis and I kissed, the woman in the couple next to us reached out and stroked my arm, then wound her fingers through mine. The pressure felt comforting as well as perverse, since the last time I’d held hands with someone I’d never spoken to was decades ago, in church.

I kissed her and said, “Comme vous êtes belle.” I had forgotten to ask Louis whether to use the formal vous or the familiar tu in a sex club. Usually you use vous for strangers, but what if you were allowing the stranger’s husband to put your hand on his cock?

“Vous aussi,” she replied. You too. She was rounded and soft all over and her husband was rounded and hard all over. He proposed to Louis that we go to another room, one with beds. They headed for a narrow bed in a corner of the room, but I insisted that we all pile onto a king-size in the center.

“I’m an American,” I said. “I like plenty of space.”

●

Last summer, I was pickpocketed while I was sitting on a bench in the American Museum of Natural History looking at a prairie diorama. I hovered so completely within it, the tips of my attention brushing the tall hairs on the hide of a grazing bison that had raised its head to look for danger, that I didn’t notice someone taking my wallet from the purse nestled against my thigh. When I discovered the loss, I thought it was a fair price to pay for being able to fly out of my body for a little while.

Growing up, I didn’t have this type of refuge. I was constantly hyperalert. At church and in school, among the evangelicals, I scrutinized myself for sin.

The psychoanalyst Edgar Levenson formed a theory of what he called “isomorphic transformation,” from the Greek for “equal in shape.” One relationship can reproduce another relationship, with every structural detail retained, but with a deceptively different appearance. You might be compelled to behave as though your boss were your mother, or a birthday party a funeral.

For me, it’s museums and sex clubs. They seem so different but feel so similar. They are both spaces where I can stop guarding myself and let pleasure in. I don’t have to worry about what others will make of me. I can turn my attention away from monitoring myself.

●

The beds in the sex club were covered with red brocaded velvet and had frames of twisted gilt. More crystal chandeliers than I would have thought advisable hung from the low ceilings. It was part Marquis de Sade, part Vegas in the Sixties, except for the condom dispensers tucked into discreet nooks.

I kissed the tops of the woman’s breasts where they bulged out of her gold dress. She shrugged me off and asked me if I really liked women. Louis had explained that interactions between groups at the club usually start with women touching and kissing one another, but few of them are really queer. Their kisses are merely seals of approval for the men moving in.

There are exceptions. After a while, when more people had joined us on the big bed, the curly-haired woman from the dance floor began caressing me. I didn’t talk to her, and the closest I got to touching her was pulling strands of her hair out of my mouth.

In a sex club, I am like an artwork. I am examined, contemplated, desired. Sometimes I step down from my pedestal, a selective Galatea choosing her lover from among an array of wishful creators. My awareness collapsed as I grew more aroused. When I came, I had no idea who was touching me or how. For a few seconds, there was no me there at all.

When I could think again, I noticed all the women around me were softly grunting “oui, oui, oui!” with every thrust, like a litter of piglets. In the club, unlike in a museum, I can act on my desire. I am no longer a girl frozen with shame, refusing to let myself commit what I thought were sins. In the anonymity of a club, I can let myself demand what I want. In taking what I’m offered there, and only there, I know I won’t have time to be disillusioned by my partners’ imperfections or awkwardness. In the club, we all remain like statues in a museum, our inner cores untouchable.

Louis waited outside with me for a cab. When it arrived, he kissed my cheek and said, “Thanks for trusting me.” I’d had a good time, but once in the fresh air, I couldn’t wait to get back to my hotel. When I got in the cab, I deleted his number from my phone.

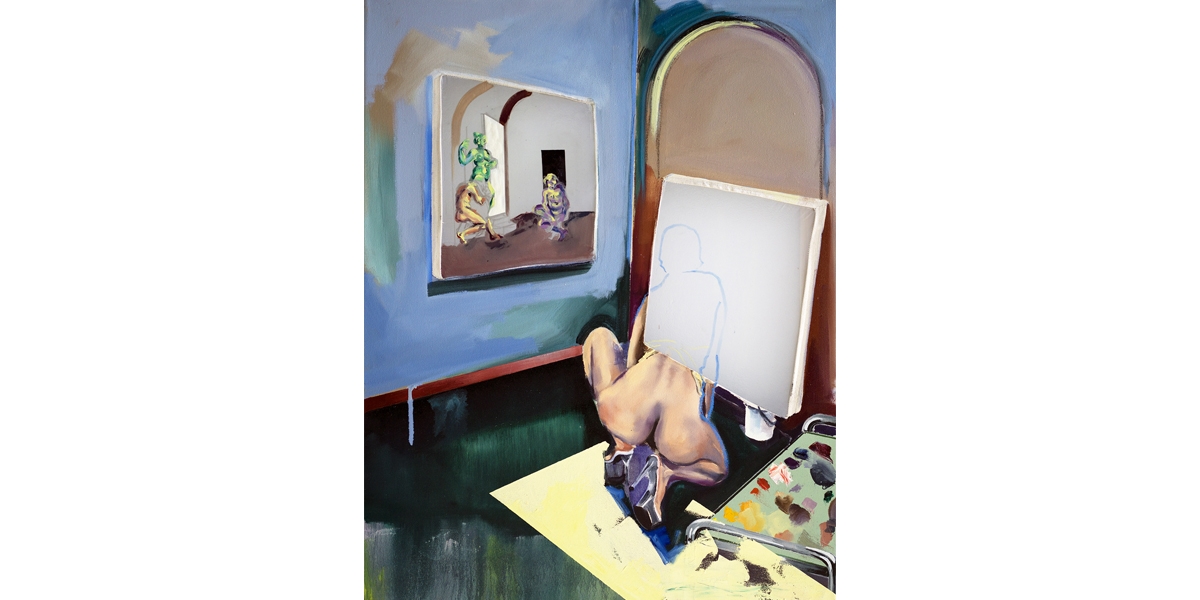

Art credit: Ellen Hanson, “Three Graces,” oil on canvas, 72 × 48 in., 2017 (top); “Relentless Self-portrait,” oil on canvas and sheer fabric, 36 × 28 in., 2020 (second image).

I spent the day at an art museum and the night at a sex club. In the museum, I tugged the hem of my dress down to cover the tops of my thigh-high stockings every time I sat on a bench. In the club, I looked up from kissing strangers to identify reproductions of erotic paintings in gilt frames: Leda and the swan, Watteau’s mistress wallowing on a silk-covered bed, Galatea—her legs still cold marble—bending to embrace Pygmalion.

I was traveling in Paris. What a contrast, I’d thought as I prepared to leave the Louvre, putting on dark lipstick in an age-spotted mirror in a gallery of decorative arts. But I’ve been reconsidering. Is the pleasure I take in museums really so different from the pleasure I find in a sex club?

●

I imagine touching the bodies I see in art. That day at the Louvre, standing before an ancient statue of a Mesopotamian ruler, I’d wanted to bend and lick the polished darkness of its bald head. I imagined it warm and cool at the same time on my tongue, like flesh and stone mixed.

It’s not as though I’m masturbating behind the display cases. But my attention to the art has an erotic edge.

The first time I remember seeing this way was at a going-away party for my fifth-grade teacher. I was flipping through a catalog as I sat on the beige-carpeted steps of a sunken living room in a house up in the foothills of Tucson, Arizona, plumes of ocotillo cactus whipping in the wind outside.

This was in the mid-Nineties. I was enrolled in an evangelical Christian private school, and my teacher was leaving to become a missionary in China. I’d cross-stitched a pillow for her, embroidering it with a loop of pink and red flowers. Our mothers praised the teacher’s Christianity and murmured about the danger she would face. Preaching the gospel was somehow illegal, or barely tolerated, in China. We were told to be jealous of our teacher for having such a good opportunity to demonstrate her faith. She might even get to be a martyr—a direct ticket to heaven, with no worrying whatsoever about any sins she might have committed here on earth.

I loved my teacher. She was young and kind, with honeyed hair that curled at the tops of her shoulders. I didn’t want to think about her leaving, so I picked up a catalog from a stack on the end table beside me. Land’s End.

It opened to a full-length photograph of a model stepping out of the ocean, wearing a blue bathing suit with a skirt ruffled around her hips to hide cellulite she did not have. Her face was long and calm. Her honeyed hair slid down to curl at the tops of her bare shoulders.

I lost all awareness of the party, and even the room, as my attention sank into the image. The tiny triangle of blue that showed beneath her skirt, between her legs, expanded to fill my vision.

My hand moved to tear out the page. I wanted to fold it tenderly and carry it home. But then I came back to myself, remembering that I was in a room full of eyes. A classmate or a mother or even my teacher might ask what I was doing. How could I explain wanting a picture of a woman in a swimsuit?

I thought of tearing out just that triangle. A blue speck of paper couldn’t be suspicious. But what if someone saw me touching the woman there as I tore?

Instead, I memorized her. I can still see her calm face, accepting that I or anyone else might look at her body. But so well did I disguise my attraction—from my classmates, from the adults and especially from myself—that it’s only now, while writing this, that I’ve realized that the model looked like my teacher, and that I loved my teacher not just for her kindness, but for her beauty.

Later, on a high school field trip to the Tucson Museum of Art, I stood close to a monochromatic painting. It was my first time at a museum. My eyes unfocused. All I could hear was a buzz, growing louder as the canvas spread out to surround me. I was nothing but a pair of floating eyes.

My knees buckled and I fell sideways against a friend. “Sorry,” I said.

“What do you think of this one?” he asked.

“It’s okay,” I said.

It was the same blue.

●

I walked through the Metro station under the Louvre. A niche on the platform displayed a plaster reproduction of one of the most famous works in the museum, Michelangelo’s The Dying Slave. It’s a sculpture of a boy caressing himself, pushing up a band of cloth wrapped around his chest, his eyes closed and his hips thrust out. So many commuters had taken this as an invitation to touch that his cock was rubbed down to a blur.

Inside the museum, looking at the original, I sensed Michelangelo looking at his model appraisingly, desirously, and looking in the same way at the marble body he was carving.

If I looked at the museum guard standing in the gallery in the same way I was looking at the statue, everyone would know I wanted to touch him, smell him, balance my shins on his thighs as I pinned him under me. The guard would notice me looking at him. He might be aroused or he might be disgusted, but he would react. The other visitors would react, too, with amusement or encouragement or scorn.

But to look at a sculpted or painted body is to contemplate without blame. Looking at Michelangelo’s desire, my own remained hidden.

●

The sex club, on the Île-Saint-Louis, had free gummy bears. A big glass jar of them, with tongs for making your selection set on a little plate. My date and I handed over our bags and phones to the proprietress, who looked like a cheerful Simone Signoret in pearls and a twin set.

She asked for our names. I said Louise. My date, whom I’d met on an app the day before, laughed and called himself Louis.

Downstairs, the proprietress’s husband manned the bar. I ordered a gin and tonic. I like the way you say it in French, slurring the words into one, ginantonic, like you’re already drunk. Next to the bar was a dance floor flanked by low tables. Laser projections spun from the ceiling—sparkles and geometric shapes. Occasionally a herd of animated pigs materialized around the feet of whoever was giving the central stripper pole a whirl.

The patrons looked like guests at the tipsy end of a wedding. The men wore suits with discarded jackets, and the women dry-clean-only dresses of the kind that are sexy without scandalizing a bride’s mother. The one exception, a woman with a tangle of curls, was wearing a dress whose back dipped so low that I could see the wings of her lower-back tattoo flapping as she wiggled to the beat.

I slid my way down the banquette to talk to a couple I heard speaking English. “I don’t know if my French is up to this!” was my opening line.

“Neither do I!” the woman replied, although it turned out that she had been living in Paris for years. She was American and her husband, his eyes bulging with anxiety, was French. They said it was their first time doing anything like this. He looked like a soldier hoping to escape the coming battle with his honor intact, if not his life.

Louis, uninterested in them, tugged on my sleeve. I said goodbye and we went deeper into the club’s back rooms. A bathroom with a shower. A room with only one bed and a door with a large window. The farthest room held a number of padded benches occupied by couples.

Here, the cellar’s shaggy stone walls were left exposed. A device of crossed supports and straps stood in a corner for floggings. The whips were hanging behind the bar. You could ask the bartender to borrow them, like darts in a pub.

As Louis and I kissed, the woman in the couple next to us reached out and stroked my arm, then wound her fingers through mine. The pressure felt comforting as well as perverse, since the last time I’d held hands with someone I’d never spoken to was decades ago, in church.

I kissed her and said, “Comme vous êtes belle.” I had forgotten to ask Louis whether to use the formal vous or the familiar tu in a sex club. Usually you use vous for strangers, but what if you were allowing the stranger’s husband to put your hand on his cock?

“Vous aussi,” she replied. You too. She was rounded and soft all over and her husband was rounded and hard all over. He proposed to Louis that we go to another room, one with beds. They headed for a narrow bed in a corner of the room, but I insisted that we all pile onto a king-size in the center.

“I’m an American,” I said. “I like plenty of space.”

●

Last summer, I was pickpocketed while I was sitting on a bench in the American Museum of Natural History looking at a prairie diorama. I hovered so completely within it, the tips of my attention brushing the tall hairs on the hide of a grazing bison that had raised its head to look for danger, that I didn’t notice someone taking my wallet from the purse nestled against my thigh. When I discovered the loss, I thought it was a fair price to pay for being able to fly out of my body for a little while.

Growing up, I didn’t have this type of refuge. I was constantly hyperalert. At church and in school, among the evangelicals, I scrutinized myself for sin.

The psychoanalyst Edgar Levenson formed a theory of what he called “isomorphic transformation,” from the Greek for “equal in shape.” One relationship can reproduce another relationship, with every structural detail retained, but with a deceptively different appearance. You might be compelled to behave as though your boss were your mother, or a birthday party a funeral.

For me, it’s museums and sex clubs. They seem so different but feel so similar. They are both spaces where I can stop guarding myself and let pleasure in. I don’t have to worry about what others will make of me. I can turn my attention away from monitoring myself.

●

The beds in the sex club were covered with red brocaded velvet and had frames of twisted gilt. More crystal chandeliers than I would have thought advisable hung from the low ceilings. It was part Marquis de Sade, part Vegas in the Sixties, except for the condom dispensers tucked into discreet nooks.

I kissed the tops of the woman’s breasts where they bulged out of her gold dress. She shrugged me off and asked me if I really liked women. Louis had explained that interactions between groups at the club usually start with women touching and kissing one another, but few of them are really queer. Their kisses are merely seals of approval for the men moving in.

There are exceptions. After a while, when more people had joined us on the big bed, the curly-haired woman from the dance floor began caressing me. I didn’t talk to her, and the closest I got to touching her was pulling strands of her hair out of my mouth.

In a sex club, I am like an artwork. I am examined, contemplated, desired. Sometimes I step down from my pedestal, a selective Galatea choosing her lover from among an array of wishful creators. My awareness collapsed as I grew more aroused. When I came, I had no idea who was touching me or how. For a few seconds, there was no me there at all.

When I could think again, I noticed all the women around me were softly grunting “oui, oui, oui!” with every thrust, like a litter of piglets. In the club, unlike in a museum, I can act on my desire. I am no longer a girl frozen with shame, refusing to let myself commit what I thought were sins. In the anonymity of a club, I can let myself demand what I want. In taking what I’m offered there, and only there, I know I won’t have time to be disillusioned by my partners’ imperfections or awkwardness. In the club, we all remain like statues in a museum, our inner cores untouchable.

Louis waited outside with me for a cab. When it arrived, he kissed my cheek and said, “Thanks for trusting me.” I’d had a good time, but once in the fresh air, I couldn’t wait to get back to my hotel. When I got in the cab, I deleted his number from my phone.

Art credit: Ellen Hanson, “Three Graces,” oil on canvas, 72 × 48 in., 2017 (top); “Relentless Self-portrait,” oil on canvas and sheer fabric, 36 × 28 in., 2020 (second image).

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.