The monsters were due in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho two weeks ago, but they never showed. There was rumor of a scout. Someone heard from somebody that a bus of Antifa was on its way from Spokane or Seattle. By nightfall, dozens of mostly white men and women had arrived with semi-automatics, handguns, American flags and tactical gear. Some expressed regret about George Floyd but warned that incoming looters were making a mistake. Insignias of far-right militia groups were spotted. It was hard to tell the difference between those who held property as sacrosanct and the whole-hog preppers. They bivouacked at either end of Sherman Avenue, a commercial strip, in case the blue line bent.

Around the same time, in Minneapolis, tired citizen patrols were barricading streets with lawn chairs and strollers, hiding trash bins, splashing porches with water and stocking up on sand, dirt and fire extinguishers. Granted curfew exemption by the mayor’s office, members of the American Indian Movement Patrol sent its volunteers to guard Native-American-owned properties. My friend in the city was sheepish about her neighbors taking photos of unfamiliar people and cars. One armed patrol, the Minnesota Freedom Riders, rode around watching for masked men who stepped too close to one of the unmolested black businesses. Jeremiah Ellison, a Minneapolis city councilman and grassroots activist, is a member. His father, former U.S. Representative Keith Ellison, is a Detroit native who remembers hiding under his bed when the National Guard came through his neighborhood in 1968 to enforce curfew after the MLK assassination. Keith Ellison is prosecuting the four officers in the Floyd case.

Though the civil rights protests and uprisings of the late 1960s have lately been evoked, little has been said about the anti-crime citizens’ crusades that began appearing around the same time, after a decade of rebellions fueled by black economic despair. As the examples in Idaho and Minneapolis suggest, the scattered, coast-to-coast block patrols of the past two weeks have been anything but homogenous. Stories of hardscrabble community organizers, from diverse racial backgrounds and social allegiances, point to the numerous ways communities have tried to fill perceived voids during societal paroxysms. The myths and realities of police absence in times of need have long shaped short-term, on-the-ground responses to a delicate question: what do you do when you think the police aren’t around, either because they are busy protecting you elsewhere or because they don’t care?

The contact high of Minneapolis’s pledge to “disband” its police has already yielded to a deflationary, bipartisan shift to the ways police could survive. This includes Joe Biden drawing the line at defunding police departments, although he has said he supports diversifying police forces and funding “community policing programs that improve relationships between officers and residents.” Leftists usually denounce community policing as code for reforms that either change nothing or, in some cases, make things worse. This reflects an ongoing heuristic debate over terminology (defund? reform? abolish? dismantle?) that obscures how these processes sometimes coalesce as cities reassess the role of the police. One example from the 1970s shows how, rather than thinking of these as mutually exclusive undertakings, we might consider how each happens at once, with varying degrees of success.

Nearly a decade before Michigan State University professor Robert Trojanowicz theorized community policing in his 1982 study of foot patrol officers in Flint, Michigan, the first black mayor of Detroit, Coleman Young, had initiated a like-minded experiment in his city, seventy miles away. Young’s strategies in community policing provided one of the earliest models of a sustained effort in a major American city to integrate black citizens in the daily administrative functions of policing, including people from autonomously organized block patrols and private security forces. Young was by no means a police abolitionist. His interest in rebuilding Detroit’s devastated corporate tax base often neutered his more progressive impulses, and late in his career he relied on deterrents, like the threat of police retaliation, to preserve a respectable image of the city. The past fifty years in Detroit reveal a series of localized successes in redefining how policing can be understood amid more holistic failure.

●

In the summer of 1968, a year after the week-long July rebellion in Detroit, among the deadliest and most destructive racial uprisings in U.S. history, a group of white “citizen-policemen” in the nearby suburb of Dearborn received a day’s training from the city’s police department for riot control. The volunteer reservists consisted of military vets, ex-Boy Scouts and white-collar workers à la Fight Club. The best-selling Kerner Report, an unprecedented document that offered explanations for what causes a racially tense “civil disorder,” had come out earlier that year. The study aimed to show how poverty, racial inequality and white racism were kindling for the kinds of riots that happened in places like Detroit, Philadelphia, Watts and Newark. Rather than attempting to resolve these issues, police departments and anxious white civilians around the country were bracing for the next conflagration. Some social scientists at the time were predicting that future riots would break down into “systematic guerilla warfare in the cities.”

The crude instantiation of this prophecy came, in Detroit, two years after the city hit a nadir of police-community relations. A violent encounter between cops and black separatists at the New Bethel Baptist Church in 1969 ended with the death of one white cop and the arrests of 142 black people, most of whom were released within 24 hours after Recorder’s Court Judge George Crockett, Jr., a black man, issued writs of habeas corpus to expedite their release. Enmity from the New Bethel Incident lingered well into 1971, when the Detroit Police Department established its STRESS unit (Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets), which black residents quickly identified as a terror regime, at best, and at worst an unmonitored murder squad. STRESS, made up of volunteer officers, some of whom had received complaints concerning their actions in 1967, became infamous for its entrapment (“decoy”) tactics. With little or no cause, elaborately disguised officers assaulted and sometimes killed unwitting black teenagers and men who may have thought they were just helping a drunkard get to the other side of the street. Over almost three years of operation, STRESS officers killed 22 people, 21 of them black, and were largely responsible for making the DPD one of the most violent police departments in the country.

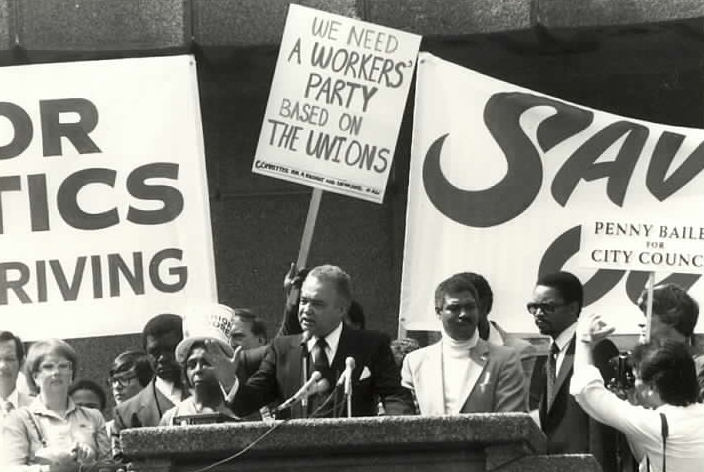

The 1973 mayoral election pitted Young, a charismatic former labor organizer, against police commissioner-turned-candidate John Nichols. From the start, the campaign was framed as a contest between a paragon of law and order and one of reform. Within months of an uncomfortably narrow victory, Young abolished STRESS and outlined a reorganization plan for the DPD. He proposed creating fifty police “mini-stations” that would be established near housing projects and supplement the work of the city’s precincts.

Like the kōban community policing system in Japan, Young’s mini-stations were intended as clear communion zones for residents and police that were organically integrated in specific neighborhoods. In The New Blue Line (1986), criminologist Jerome Skolnick described them as unique crapshoots that relied on the personal investment of volunteer DPD officers. Much of the work was a bureaucratic slog, and mini-station cops were usually prohibited from responding directly to emergency scenarios (they advised walk-ins to contact 911 for urgent matters). But over the course of Young’s twenty-year career as mayor, mini-stations were generally appreciated by the communities that had them.

Mini-station officers issued bike licenses, taught rape prevention and home security classes to senior citizens, built makeshift libraries using donated books, joined school boards and residents associations, got involved with nearby mental health clinics, checked kids’ Halloween candy for razors and dressed up as Santa and the Easter Bunny. In at least two cases, they unexpectedly helped women deliver their babies. Then, as now, many cops scoffed at the breadth of responsibilities they were sometimes expected to fulfill, which led Police Chief William Hart to formally split mini-station operations from the precincts in 1980. DPD officers in the precincts viewed the mini-stations as wasteful and ineffective, even after Young enlisted James Bannon, the former STRESS commander, to optimize their performance.

The operation was seen as a glorified PR move that threatened officers’ standing as enforcers of the law and, in relying heavily on civilian cooperation, quite possibly endangered their jobs. “Hell,” one precinct officer in 1974 retorted, “are we going to be cops out busting crooks or goddamn social workers?” This sentiment sharply contrasted with Skolnick’s characterization of the mini-station cop:

Perhaps the mini-station officer’s most important trait is the capacity to show concern over and over again for the specific, petty, undramatic problems of ordinary people. … Whether a mini-station works at all depends in large measure on the empathy, patience, and understanding of officers in handling the mundane problems of individual lives.

Some of the ambitious police reform goals of Young’s first administration—most notably his challenge to the entrenched “last hired, first fired” seniority system and an affirmative-action policy to increase the number of black officers from 18 to 50 percent of the force in four years—were tamed by the budding global recession and resistance from powerful unions like the Detroit Police Officer’s Association. If his recurring invitations for thousands of civilian volunteers to join the police reserves, organize neighborhood city halls and help staff mini-stations were primarily catalyzed by a refreshing vision of what the police could be, municipal budget shortfalls were also a consideration.

Lawsuits followed Young’s decisions to retain black officers and deploy civilian reservists (“scabs,” beat cops called them) at the expense of more senior whites, particularly in a period of economic contraction. From his earliest days in office, predicting a spate of “blue flus,” Young queried churches, ethnic clubs and trade union halls for volunteers. This included the Shrine of the Black Madonna #1, the principal church of the Black Christian Nationalist movement, which had as much in common with MLK’s Poor People Campaign as any Protestant denomination. Its leader, Albert Cleage, Jr., had a hand in securing black votes for Young in 1973 through his organization, the Black Slate.

For this publication, I recently wrote about the Shrine and Cleage, a black minister who called for radical self-sufficiency in black communities. His fame in the Sixties and Seventies was comparable to that of Rev. Dr. William Barber II today. Shelley McIntosh, a Detroit-based educator and former Shrine member who closely advised Cleage, remembers when Young asked him to solicit one hundred volunteers for the DPD reserve force. McIntosh was one of the Shrine members who immediately raised her hand.

“I took gun training, became a marksperson,” McIntosh told me of her reserve training. “I took the test, got my uniform, but then I transferred to Houston.” McIntosh and Cleage spent decades at the Houston satellite of the Shrine. As one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the South, Houston was an ideal expansion site for the church. Many former Shrine members who grew up in the church still live in Houston, where George Floyd grew up, and turned to one another or were out protesting following his death. Jamar Walker, six years Floyd’s junior, attended the same high school. He was disappointed, if not surprised, by the lack of a coordinated response from the Shrine, which ex-members say has deviated from the revolutionary ethic Cleage advocated in the Seventies and Eighties. “Back in the day, when things were happening in South Africa and Rwanda, the Shrine was involved,” Walker said. “They’d have people come and speak. Now it’s not like that… Usually they’d be on the frontlines, on the news, next to the guy.”

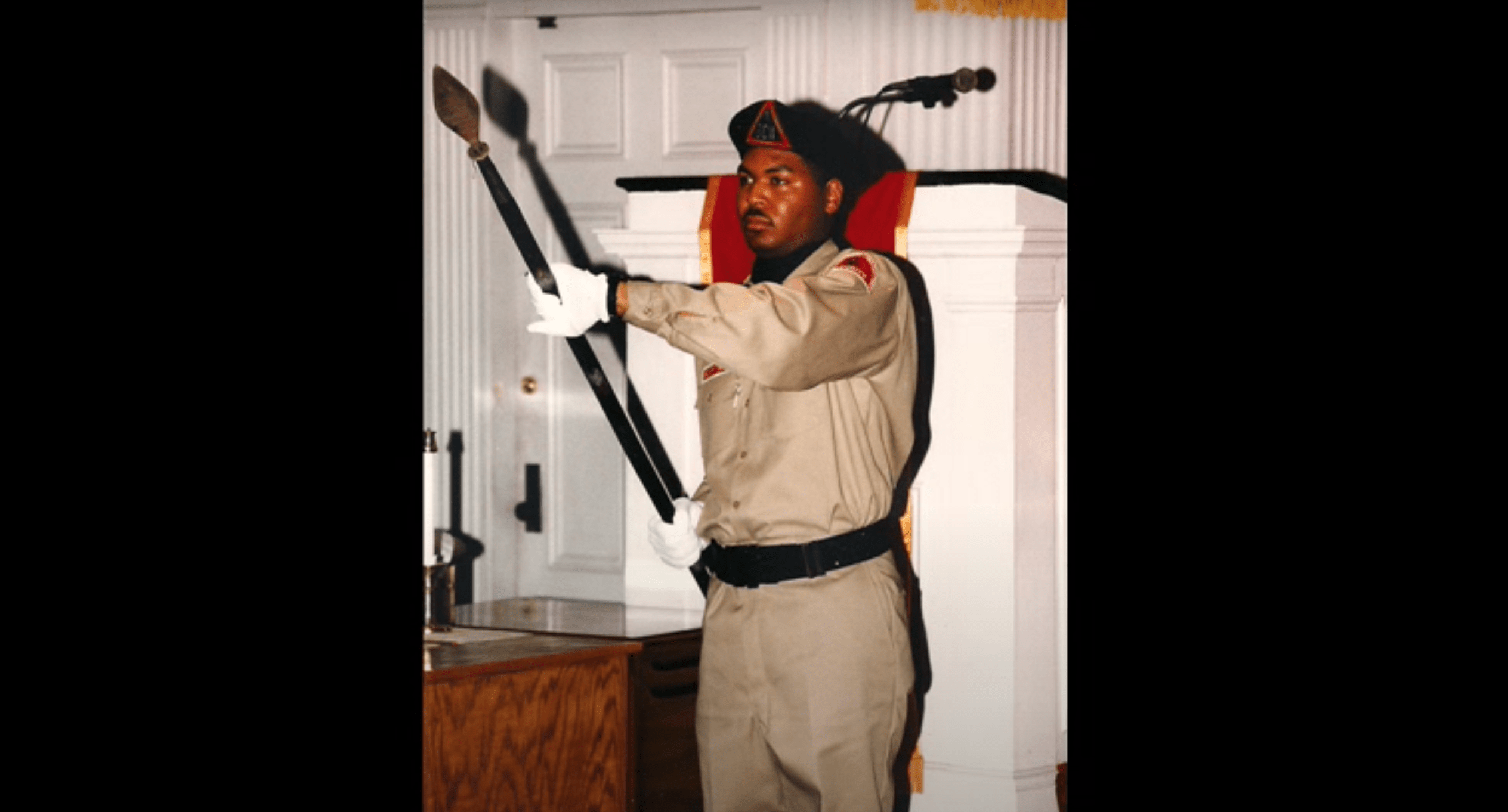

Self-sufficiency, communalism and a programmatically instilled sense of empathy were defining features of black security groups organized in the Sixties and Seventies in response to racial hatred. They were far cries from white “relief men” and their descendants: provocateurs who are not-so-secretly agitating for a doomsday-themed race war. It is true that the Shrine’s mixed-gender, unarmed patrol, the Maccabees, wore berets and other revolutionary attire like the Black Panther patrols in late-Sixties Oakland. Unlike modern-day minutemen, however, the Maccabees’ visual language of deterrence developed out of collective experiences of racial violence rather than individual delusions of invasion. That the Maccabees didn’t carry weapons and yet wore military chic wasn’t proof of an identity crisis. They were the infantry in what Cleage hoped would become a worldwide revolution to free blacks from “slave thinking,” or overreliance on institutions built by white people. The safeguarding of black communities was mainly envisioned as economic and intellectual combat. Sometimes arms couldn’t be avoided, when self-defense was necessary, but they were usually just for suckers.

Despite Young’s affiliation with the Shrine, the Maccabees embodied a citizen-led approach to public safety that was distinct from the mayor’s own community policing programs. Though there was cross-fertilization between the Shrine and the DPD, the Maccabees exemplified the police abolitionist’s dream: a unit born of a communitarian movement that educated its wards in global histories of colonialism, slavery and racial capitalism, and resolved conflict as a family around a dinner table might, through caring means.

●

If Detroit’s 1973 mayoral campaign was a referendum on law and order, the 1977 election reflected the city’s growing anxieties about crime. Neighborhood watches passed out whistles, instituted buddy systems and gave its foot patrols stickers saying things like “My neighbor is watching my house.” Even as police layoffs continued, mini-stations kept cropping up and Young’s community outreach persisted. By the mid-Eighties, when the crack epidemic was raging in Detroit and the city became known as America’s “murder capital,” reservists were being used to help cops protect sports stadiums and other venues even as they were shut out of policy-making decisions about issues like use of force, stop-and-frisk procedures and confrontations with mentally ill individuals. Desperate reactionism replaced crime prevention and relationship-building as the guiding logic of civilian involvement in police affairs. By the early Nineties, the DPD had shifted its focus to building out patrol forces, which meant significantly slashing crime-prevention staff. Facing a $50 million municipal deficit in 1991, an aging Young called police hiring his top priority.

The administration of Dennis Archer, elected mayor in 1993, delivered the coup de grâce to the mini-station fantasy by reabsorbing them into the precincts. For the next twenty years, subsequent black mayors and mayoral hopefuls who embraced zero-tolerance policies and broken-window thinking periodically voiced desires to reopen mini-stations, and in some cases did, so that a withered police force could focus on things like dispersing ordinance violators and manning the corridors of black high schools. This was notably the case in 2008 and 2012, under mayors who respectively faced the Great Recession and the city’s impending bankruptcy. A consent decree that the DPD entered with the Justice Department in 2003 after reports of unconstitutional conduct further incentivized city leaders to reform the department under strict guidelines. The decree expired in 2016. The trial-and-error period was over.

Former Shrine members in Detroit and Houston agree that, if there is going to be a moment of national reckoning over the role of the police, this is it. They also believe the absence of centralized leadership, in the case of Black Lives Matter and the idiosyncratic protests, as well as Democratic indecisiveness on whether to prioritize police abolition over reform, pose formidable threats to the cause. Malik Ware, whose mother joined the Detroit Shrine in the early Seventies, said one thing that made the Shrine such an effective social and political force was the covenant its constituents swore to uphold upon joining: to materially and emotionally protect the members of its “black nation.” Apart from the convenience of ideological consensus, the shared covenant often eased conflict resolution in the Shrine. Was the situation violating some baseline standard of mutual care? Was escalation worth the fallout, perhaps something as tacitly distressing as incurring the displeasure of one’s spiritual sister or mother? “It’s not so much we can do outside of what we build for ourselves,” Ware said.

Italo Johnson, McIntosh’s son, lives in Houston with a bevy of energetic young boys who have been spurring him to take them to the protests. Upon leaving the Shrine, perhaps the thing that surprises longtime members most, beside their ability to handle arguments more productively than their peers, is the disinclination to live a life that is not in some way lived for strangers. Johnson guessed that if Floyd had been killed while Cleage was still alive (he died in 2000), the pastor would’ve immediately dispatched Shrine members to the streets, in front of shuttered businesses, having them distribute flyers and invite passersby to the church. “He would have everybody ready to work, everybody ready to build, everybody ready to organize,” Johnson said.

The cautious optimism of the unnamed movement—and the sense that there is something invigoratingly new about it—has already been somewhat undermined by the reflexive aversion of even sympathetic elected officials. Often we dismiss as unattainable those scenarios that demand an intentionally blind movement toward the future. This explains the flabbergasted reactions to the new, amorphous district in Seattle variously known as the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) or the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest (CHOP). People have compared it to Burning Man, a secessionist enclave or, as one visitor called it, a “social change ecosystem.” Here occupiers have barred police and zoned off several blocks, an arrangement they hope will last at least until a list of thirty demands are met, including the total gutting of the Seattle PD, the end of juvenile prisons, and freedom for “people to create localized anti-crime systems.”

The “CHAZites” are far from the Shrine’s Maccabees on the spectrum of experiments in self-rule, though both approximate ways, however downsized and provisional, of imagining police-free societies. The ambiguity of the endeavor, which some activists on the inside suspect will compromise it, is also sort of the point. Seattle mayor Jenny Durkan refuted Trump’s designation of the protestors as domestic terrorists, calling them patriotic and vowing to invest $100 million in minority communities even after marchers gathered in city hall to demand her resignation. Seattle law enforcement officials are reportedly frustrated and want to take the precinct back. For now, though, there’s no timeline for their return.

Photo credits: Shrine of the Black Madonna (YouTube); Coleman Young (CC / BY)

The monsters were due in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho two weeks ago, but they never showed. There was rumor of a scout. Someone heard from somebody that a bus of Antifa was on its way from Spokane or Seattle. By nightfall, dozens of mostly white men and women had arrived with semi-automatics, handguns, American flags and tactical gear. Some expressed regret about George Floyd but warned that incoming looters were making a mistake. Insignias of far-right militia groups were spotted. It was hard to tell the difference between those who held property as sacrosanct and the whole-hog preppers. They bivouacked at either end of Sherman Avenue, a commercial strip, in case the blue line bent.

Around the same time, in Minneapolis, tired citizen patrols were barricading streets with lawn chairs and strollers, hiding trash bins, splashing porches with water and stocking up on sand, dirt and fire extinguishers. Granted curfew exemption by the mayor’s office, members of the American Indian Movement Patrol sent its volunteers to guard Native-American-owned properties. My friend in the city was sheepish about her neighbors taking photos of unfamiliar people and cars. One armed patrol, the Minnesota Freedom Riders, rode around watching for masked men who stepped too close to one of the unmolested black businesses. Jeremiah Ellison, a Minneapolis city councilman and grassroots activist, is a member. His father, former U.S. Representative Keith Ellison, is a Detroit native who remembers hiding under his bed when the National Guard came through his neighborhood in 1968 to enforce curfew after the MLK assassination. Keith Ellison is prosecuting the four officers in the Floyd case.

Though the civil rights protests and uprisings of the late 1960s have lately been evoked, little has been said about the anti-crime citizens’ crusades that began appearing around the same time, after a decade of rebellions fueled by black economic despair. As the examples in Idaho and Minneapolis suggest, the scattered, coast-to-coast block patrols of the past two weeks have been anything but homogenous. Stories of hardscrabble community organizers, from diverse racial backgrounds and social allegiances, point to the numerous ways communities have tried to fill perceived voids during societal paroxysms. The myths and realities of police absence in times of need have long shaped short-term, on-the-ground responses to a delicate question: what do you do when you think the police aren’t around, either because they are busy protecting you elsewhere or because they don’t care?

The contact high of Minneapolis’s pledge to “disband” its police has already yielded to a deflationary, bipartisan shift to the ways police could survive. This includes Joe Biden drawing the line at defunding police departments, although he has said he supports diversifying police forces and funding “community policing programs that improve relationships between officers and residents.” Leftists usually denounce community policing as code for reforms that either change nothing or, in some cases, make things worse. This reflects an ongoing heuristic debate over terminology (defund? reform? abolish? dismantle?) that obscures how these processes sometimes coalesce as cities reassess the role of the police. One example from the 1970s shows how, rather than thinking of these as mutually exclusive undertakings, we might consider how each happens at once, with varying degrees of success.

Nearly a decade before Michigan State University professor Robert Trojanowicz theorized community policing in his 1982 study of foot patrol officers in Flint, Michigan, the first black mayor of Detroit, Coleman Young, had initiated a like-minded experiment in his city, seventy miles away. Young’s strategies in community policing provided one of the earliest models of a sustained effort in a major American city to integrate black citizens in the daily administrative functions of policing, including people from autonomously organized block patrols and private security forces. Young was by no means a police abolitionist. His interest in rebuilding Detroit’s devastated corporate tax base often neutered his more progressive impulses, and late in his career he relied on deterrents, like the threat of police retaliation, to preserve a respectable image of the city. The past fifty years in Detroit reveal a series of localized successes in redefining how policing can be understood amid more holistic failure.

●

In the summer of 1968, a year after the week-long July rebellion in Detroit, among the deadliest and most destructive racial uprisings in U.S. history, a group of white “citizen-policemen” in the nearby suburb of Dearborn received a day’s training from the city’s police department for riot control. The volunteer reservists consisted of military vets, ex-Boy Scouts and white-collar workers à la Fight Club. The best-selling Kerner Report, an unprecedented document that offered explanations for what causes a racially tense “civil disorder,” had come out earlier that year. The study aimed to show how poverty, racial inequality and white racism were kindling for the kinds of riots that happened in places like Detroit, Philadelphia, Watts and Newark. Rather than attempting to resolve these issues, police departments and anxious white civilians around the country were bracing for the next conflagration. Some social scientists at the time were predicting that future riots would break down into “systematic guerilla warfare in the cities.”

The crude instantiation of this prophecy came, in Detroit, two years after the city hit a nadir of police-community relations. A violent encounter between cops and black separatists at the New Bethel Baptist Church in 1969 ended with the death of one white cop and the arrests of 142 black people, most of whom were released within 24 hours after Recorder’s Court Judge George Crockett, Jr., a black man, issued writs of habeas corpus to expedite their release. Enmity from the New Bethel Incident lingered well into 1971, when the Detroit Police Department established its STRESS unit (Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets), which black residents quickly identified as a terror regime, at best, and at worst an unmonitored murder squad. STRESS, made up of volunteer officers, some of whom had received complaints concerning their actions in 1967, became infamous for its entrapment (“decoy”) tactics. With little or no cause, elaborately disguised officers assaulted and sometimes killed unwitting black teenagers and men who may have thought they were just helping a drunkard get to the other side of the street. Over almost three years of operation, STRESS officers killed 22 people, 21 of them black, and were largely responsible for making the DPD one of the most violent police departments in the country.

The 1973 mayoral election pitted Young, a charismatic former labor organizer, against police commissioner-turned-candidate John Nichols. From the start, the campaign was framed as a contest between a paragon of law and order and one of reform. Within months of an uncomfortably narrow victory, Young abolished STRESS and outlined a reorganization plan for the DPD. He proposed creating fifty police “mini-stations” that would be established near housing projects and supplement the work of the city’s precincts.

Like the kōban community policing system in Japan, Young’s mini-stations were intended as clear communion zones for residents and police that were organically integrated in specific neighborhoods. In The New Blue Line (1986), criminologist Jerome Skolnick described them as unique crapshoots that relied on the personal investment of volunteer DPD officers. Much of the work was a bureaucratic slog, and mini-station cops were usually prohibited from responding directly to emergency scenarios (they advised walk-ins to contact 911 for urgent matters). But over the course of Young’s twenty-year career as mayor, mini-stations were generally appreciated by the communities that had them.

Mini-station officers issued bike licenses, taught rape prevention and home security classes to senior citizens, built makeshift libraries using donated books, joined school boards and residents associations, got involved with nearby mental health clinics, checked kids’ Halloween candy for razors and dressed up as Santa and the Easter Bunny. In at least two cases, they unexpectedly helped women deliver their babies. Then, as now, many cops scoffed at the breadth of responsibilities they were sometimes expected to fulfill, which led Police Chief William Hart to formally split mini-station operations from the precincts in 1980. DPD officers in the precincts viewed the mini-stations as wasteful and ineffective, even after Young enlisted James Bannon, the former STRESS commander, to optimize their performance.

The operation was seen as a glorified PR move that threatened officers’ standing as enforcers of the law and, in relying heavily on civilian cooperation, quite possibly endangered their jobs. “Hell,” one precinct officer in 1974 retorted, “are we going to be cops out busting crooks or goddamn social workers?” This sentiment sharply contrasted with Skolnick’s characterization of the mini-station cop:

Some of the ambitious police reform goals of Young’s first administration—most notably his challenge to the entrenched “last hired, first fired” seniority system and an affirmative-action policy to increase the number of black officers from 18 to 50 percent of the force in four years—were tamed by the budding global recession and resistance from powerful unions like the Detroit Police Officer’s Association. If his recurring invitations for thousands of civilian volunteers to join the police reserves, organize neighborhood city halls and help staff mini-stations were primarily catalyzed by a refreshing vision of what the police could be, municipal budget shortfalls were also a consideration.

Lawsuits followed Young’s decisions to retain black officers and deploy civilian reservists (“scabs,” beat cops called them) at the expense of more senior whites, particularly in a period of economic contraction. From his earliest days in office, predicting a spate of “blue flus,” Young queried churches, ethnic clubs and trade union halls for volunteers. This included the Shrine of the Black Madonna #1, the principal church of the Black Christian Nationalist movement, which had as much in common with MLK’s Poor People Campaign as any Protestant denomination. Its leader, Albert Cleage, Jr., had a hand in securing black votes for Young in 1973 through his organization, the Black Slate.

For this publication, I recently wrote about the Shrine and Cleage, a black minister who called for radical self-sufficiency in black communities. His fame in the Sixties and Seventies was comparable to that of Rev. Dr. William Barber II today. Shelley McIntosh, a Detroit-based educator and former Shrine member who closely advised Cleage, remembers when Young asked him to solicit one hundred volunteers for the DPD reserve force. McIntosh was one of the Shrine members who immediately raised her hand.

“I took gun training, became a marksperson,” McIntosh told me of her reserve training. “I took the test, got my uniform, but then I transferred to Houston.” McIntosh and Cleage spent decades at the Houston satellite of the Shrine. As one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the South, Houston was an ideal expansion site for the church. Many former Shrine members who grew up in the church still live in Houston, where George Floyd grew up, and turned to one another or were out protesting following his death. Jamar Walker, six years Floyd’s junior, attended the same high school. He was disappointed, if not surprised, by the lack of a coordinated response from the Shrine, which ex-members say has deviated from the revolutionary ethic Cleage advocated in the Seventies and Eighties. “Back in the day, when things were happening in South Africa and Rwanda, the Shrine was involved,” Walker said. “They’d have people come and speak. Now it’s not like that… Usually they’d be on the frontlines, on the news, next to the guy.”

Self-sufficiency, communalism and a programmatically instilled sense of empathy were defining features of black security groups organized in the Sixties and Seventies in response to racial hatred. They were far cries from white “relief men” and their descendants: provocateurs who are not-so-secretly agitating for a doomsday-themed race war. It is true that the Shrine’s mixed-gender, unarmed patrol, the Maccabees, wore berets and other revolutionary attire like the Black Panther patrols in late-Sixties Oakland. Unlike modern-day minutemen, however, the Maccabees’ visual language of deterrence developed out of collective experiences of racial violence rather than individual delusions of invasion. That the Maccabees didn’t carry weapons and yet wore military chic wasn’t proof of an identity crisis. They were the infantry in what Cleage hoped would become a worldwide revolution to free blacks from “slave thinking,” or overreliance on institutions built by white people. The safeguarding of black communities was mainly envisioned as economic and intellectual combat. Sometimes arms couldn’t be avoided, when self-defense was necessary, but they were usually just for suckers.

Despite Young’s affiliation with the Shrine, the Maccabees embodied a citizen-led approach to public safety that was distinct from the mayor’s own community policing programs. Though there was cross-fertilization between the Shrine and the DPD, the Maccabees exemplified the police abolitionist’s dream: a unit born of a communitarian movement that educated its wards in global histories of colonialism, slavery and racial capitalism, and resolved conflict as a family around a dinner table might, through caring means.

●

If Detroit’s 1973 mayoral campaign was a referendum on law and order, the 1977 election reflected the city’s growing anxieties about crime. Neighborhood watches passed out whistles, instituted buddy systems and gave its foot patrols stickers saying things like “My neighbor is watching my house.” Even as police layoffs continued, mini-stations kept cropping up and Young’s community outreach persisted. By the mid-Eighties, when the crack epidemic was raging in Detroit and the city became known as America’s “murder capital,” reservists were being used to help cops protect sports stadiums and other venues even as they were shut out of policy-making decisions about issues like use of force, stop-and-frisk procedures and confrontations with mentally ill individuals. Desperate reactionism replaced crime prevention and relationship-building as the guiding logic of civilian involvement in police affairs. By the early Nineties, the DPD had shifted its focus to building out patrol forces, which meant significantly slashing crime-prevention staff. Facing a $50 million municipal deficit in 1991, an aging Young called police hiring his top priority.

The administration of Dennis Archer, elected mayor in 1993, delivered the coup de grâce to the mini-station fantasy by reabsorbing them into the precincts. For the next twenty years, subsequent black mayors and mayoral hopefuls who embraced zero-tolerance policies and broken-window thinking periodically voiced desires to reopen mini-stations, and in some cases did, so that a withered police force could focus on things like dispersing ordinance violators and manning the corridors of black high schools. This was notably the case in 2008 and 2012, under mayors who respectively faced the Great Recession and the city’s impending bankruptcy. A consent decree that the DPD entered with the Justice Department in 2003 after reports of unconstitutional conduct further incentivized city leaders to reform the department under strict guidelines. The decree expired in 2016. The trial-and-error period was over.

Former Shrine members in Detroit and Houston agree that, if there is going to be a moment of national reckoning over the role of the police, this is it. They also believe the absence of centralized leadership, in the case of Black Lives Matter and the idiosyncratic protests, as well as Democratic indecisiveness on whether to prioritize police abolition over reform, pose formidable threats to the cause. Malik Ware, whose mother joined the Detroit Shrine in the early Seventies, said one thing that made the Shrine such an effective social and political force was the covenant its constituents swore to uphold upon joining: to materially and emotionally protect the members of its “black nation.” Apart from the convenience of ideological consensus, the shared covenant often eased conflict resolution in the Shrine. Was the situation violating some baseline standard of mutual care? Was escalation worth the fallout, perhaps something as tacitly distressing as incurring the displeasure of one’s spiritual sister or mother? “It’s not so much we can do outside of what we build for ourselves,” Ware said.

Italo Johnson, McIntosh’s son, lives in Houston with a bevy of energetic young boys who have been spurring him to take them to the protests. Upon leaving the Shrine, perhaps the thing that surprises longtime members most, beside their ability to handle arguments more productively than their peers, is the disinclination to live a life that is not in some way lived for strangers. Johnson guessed that if Floyd had been killed while Cleage was still alive (he died in 2000), the pastor would’ve immediately dispatched Shrine members to the streets, in front of shuttered businesses, having them distribute flyers and invite passersby to the church. “He would have everybody ready to work, everybody ready to build, everybody ready to organize,” Johnson said.

The cautious optimism of the unnamed movement—and the sense that there is something invigoratingly new about it—has already been somewhat undermined by the reflexive aversion of even sympathetic elected officials. Often we dismiss as unattainable those scenarios that demand an intentionally blind movement toward the future. This explains the flabbergasted reactions to the new, amorphous district in Seattle variously known as the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) or the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest (CHOP). People have compared it to Burning Man, a secessionist enclave or, as one visitor called it, a “social change ecosystem.” Here occupiers have barred police and zoned off several blocks, an arrangement they hope will last at least until a list of thirty demands are met, including the total gutting of the Seattle PD, the end of juvenile prisons, and freedom for “people to create localized anti-crime systems.”

The “CHAZites” are far from the Shrine’s Maccabees on the spectrum of experiments in self-rule, though both approximate ways, however downsized and provisional, of imagining police-free societies. The ambiguity of the endeavor, which some activists on the inside suspect will compromise it, is also sort of the point. Seattle mayor Jenny Durkan refuted Trump’s designation of the protestors as domestic terrorists, calling them patriotic and vowing to invest $100 million in minority communities even after marchers gathered in city hall to demand her resignation. Seattle law enforcement officials are reportedly frustrated and want to take the precinct back. For now, though, there’s no timeline for their return.

Photo credits: Shrine of the Black Madonna (YouTube); Coleman Young (CC / BY)

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.