I grew up in a leafy residential neighborhood less than a mile from Wrigley Field, the home of the Chicago Cubs. All my friends—virtually everyone I knew—were Cubs fans. If there are tics, habits and emotional dependencies common to fans of every sport and franchise, there is also something specific to the community of the faithful surrounding each individual team. Cubs fans are known for being happy, prosperous and good looking. They enjoy drinking, sunbathing, and having fun at the ballpark with their incredibly sexy girlfriends. Disturbingly, at least for those of us who hate them, they appear relatively unfazed by the stunning ineptitude of their team, which has set a standard for ingenuity in managing to avoid winning a World Series since 1908.

Chicago’s other baseball team, the White Sox, played on the South Side, where nobody I knew lived. They played in a ballpark nobody liked, in a neighborhood you had to lock your doors just to drive through. The stands were mostly empty for Sox games; those who did show up were neither attractive nor happy, though they were often drunk. For several years, my father was one of the few adults I knew who would risk subjecting his child to the perils of Sox Park at night—and in 1988, Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf, citing a lack of local support, came within hours of following through on a threat to relocate the team to Florida. All through my childhood, the news that I was a Sox fan was met with gasps of mock surprise or eyebrows quizzically raised: Why root for the Sox?

I rooted for the Sox because it ran in the family, as philandering or alcoholism run in other families. My father—a sober, analytical man, dispassionate to a fault at home and virtually the embodiment of the Protestant ethic at work—was reliably unreasonable on two subjects, Israel being the other. But if talk of U.N. double standards tended to turn him hectoring and shrill, his disquisitions on the Sox were leavened by anxiety, sadness and the withering pessimism we reserve for the things with the potential to hurt us worst. He had grown up on the South Side, back when the Jews still lived down there, and his father had rooted for the Sox. And his father had passed down to him the disease of being a Sox fan (this is the kind of thing he would say), and now he had passed it down selfishly, carelessly, to his son.

He taught me to live and die with every game, every batter, every pitch. I say “taught” although it was inadvertent; he did it, and (to my mother’s horror) I imitated him. Every night of the summer would unfurl the same sentimental drama. The two of us, having kept track of the game from odd angles during dinner, would settle in front of the TV for the final innings. To each other, we spoke exclusively of defeat; in our hearts, we longed frantically for a win. On the nights we were prevented from watching, I remember him returning to the dinner table or the party, his tiny cordless radio tucked into his pocket, with the dreadful news. As we locked eyes, I received my introduction to the idea that there were things in the world that could determine my happiness—things that would simply act on me, and that I could do nothing about. The clipped decrees came like bursts of fate: “Sox up big”; “Sox leading late”; “Sox down but threatening.” And, of course, worst of all: “It’s over. Sox lose.”

What would follow? A swift, surely chemical despair. Some sense of the unfairness of the world, abetted by the feeling that I was suffocating or drowning and with an outward consequence of extreme crabbiness. It was imperative that my mother not speak for at least ten minutes. If I was around strangers, I could occasionally conceal the extremity of my feelings behind a caustic black humor; sometimes I could resist the temptation to lay my head on the table or fling my body to the floor. My politically-minded friends said they felt this way when they woke up to discover George Bush had been re-elected in 2004—I feel it somewhere between 65 and 90 nights each summer, depending on the record of my local team. Immersive video games, television and hard liquor would help in later years; blackness and sleep was best. In the morning, I could begin preparing for the next game.

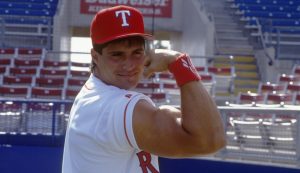

The Sox lost a lot all through the 1980s; then, just as I became old enough to follow them conscientiously as a fan, they began to win more than they lost. A new ballpark and a series of strong draft picks—Robin Ventura, Alex Fernandez, Frank Thomas—catapulted the team to prominence in the American League Central, where they competed for division titles nearly every year. I will remember the 90s in baseball for the resurgence of the Sox, the return of their fan base from whatever distant suburbs they had disappeared to, and the team’s two forays into the playoffs, in 1993 and 2000 (even though both culminated in quick, soul-crushing defeats). Also for the ascendency of Thomas, a mass of a man, formerly a tight end at Auburn, soon known on the South Side as the “Big Hurt” for the almost unprecedented harm he was capable of inflicting on a baseball. Thomas’s at bats, in those days, were events—and I watched closely. It seemed the secret to life might lurk in the way he lifted his back heel just slightly off the ground as he made contact, or in the discernment he showed holding back his bat on pitches destined to veer millimeters outside the zone. My father, always sensitive to the importance of sample size, conceded eventually that we were in the presence of genius. The evidence, to me at least, seemed incontrovertible.

I was lucky. My innocence as a fan coincided fortuitously with that of the sport. For it is already clear that the decade will be remembered by history for very different sorts of reasons. According to a raft of recent articles, books and documentaries—including Ken Burns’s exhaustive chronicle, The Tenth Inning—the real drama during those years unfolded off the field, behind closed doors, in workout facilities and pharmaceutical labs and doctors’ offices. Some players—probably a lot of players—cheated; many of the most impressive performances were made possible by drugs. If we could have guessed about such things at the time, now we know too much to ignore them. Whatever we may wish to be the case, history will remember the 90s in baseball as the beginning of the Steroid Era.

●

Stories about steroids in baseball are often headlined lasciviously—steroids was an “orgy”; the whole league was “juiced”—although the progression itself was predictable, even anodyne. As the action on the field grew more extreme, the players transformed themselves into veritable drones of efficiency. They did so in conjunction with the arrival of a new generation of owners, like Tom Hicks in Texas and John Henry in Boston, who had migrated to the sport from the corporate world. Expecting returns commensurate with their sizable investments, such owners were impatient with conduct detrimental to performance on the field. Steroids were the opposite of all earlier drugs in this respect. Instead of distracting players from their job, they helped them perform at what had previously been considered impossibly high levels. The juiciest bits from the steroid memoirs involve grown men disappearing into bathroom stalls to shoot each other in the buttocks with a needle. The visible consequences included acne, bloating, shrunken testicles, and hundreds upon hundreds of home runs.

It was progress, said many. Throughout the 90s, players would recall how much worse things had been before, when, rather than lifting weights and rubbing themselves with bionic lotions, they had snorted cocaine, driven drunk, and banged groupies in the bullpen. Mets clubhouse assistant Kirk Radomski, a key witness for the government sponsored Mitchell Report on steroids in 2007, recalls an infamous New York Mets clubhouse teeming with recreational drugs and X-rated practical jokes. Indeed, the mid-80s Mets, led by Darryl Strawberry, Doc Gooden and David Cone, defined what could one day be known as the performance de-hancing drug era in baseball. The first drug test that Radomski describes in his memoir, Bases Loaded, is Gooden’s—and it was not for steroids.

Gooden, a toothpick-skinny pitcher from Florida, had burst on the scene in 1984, winning 17 games and striking out a staggering 276 hitters at the age of nineteen. According to Radomski, Gooden never took steroids or even lifted weights, which may be one reason he failed to fulfill his prodigious promise, unlike the second best young pitcher in baseball during those years, the Boston Red Sox’ Roger Clemens (who did both). Gooden had other problems, though. In 1986, he was arrested for fighting with police in Tampa. The next year he was institutionalized after testing positive for cocaine during spring training. He would struggle his whole career with substance abuse, entering rehabilitation facilities several times and being arrested for drunk driving twice. Radomski claims he helped Gooden cheat on two urine tests in 1988. In 1991, Gooden was accused along with two teammates of rape (the charges were later dropped); in 2005, he was convicted of a misdemeanor after punching his girlfriend.

The young pitcher became a symbol for his era. Drugs, alcohol and spousal abuse were public relations nightmares for the sport throughout the 80s. Steroids, traditionally associated with track and field and football, only became popular in baseball toward the end of the decade. The earliest case Radomski recalls from his days with the Mets was that of outfielder Lenny Dykstra, who arrived at spring training having added 35 pounds of muscle in 1990. Dykstra was a gritty 27-year-old slap hitter—he’d earned the nickname “Nails” for his supposed toughness—coming off an abysmal 1989 season. In 1990, he posted career highs in nearly every offensive category despite tailing off in the second half due to what Radomski diagnoses as an improperly spaced “cycling” technique with his drugs.

Baseball, it had always been thought, was a sport requiring agility, finesse and stamina. The conventional wisdom was that excessive weight lifting and supplements slowed players down and exposed them to injury. Such assumptions had begun to be revised a few years earlier based on developments in the Bay Area, where, in 1987, the Oakland A’s Bunyonesque first baseman Mark McGwire set a rookie record with 49 home runs. McGwire joined outfielder Jose Canseco to form an imposing duo in the middle of the A’s lineup soon known, based on their body-builder physiques and the homoerotic forearm bump they invented for celebrating long balls, as the “Bash Brothers.” The A’s reached the World Series three straight years from 1988-1990, winning in 1989. In 1988, Canseco won the league’s Most Valuable Player (MVP) award after becoming the first player ever to hit forty home runs and steal forty bases in the same season. Taunted by Red Sox fans in the playoffs for being a steroid cheat, the slugger responded with a smile and a gaudily flexed bicep. The next year, he was rewarded with the richest contract in major league history.

Canseco’s memoir, Juiced, is the most revealing book yet written about steroids. This is because it is the only book whose author is unabashedly pro-steroids. Canseco never pretends his success was the result of hard work, or that steroids were merely a hedge against injuries (both assertions were made by McGwire after he admitted using in 2010). Rather, steroids were “the key to it all”; combined with growth hormone, their effect was “just incredible.” In the future, Canseco is certain that everyone will use:

I have no doubt whatsoever that intelligent, informed use of steroids, combined with human growth hormone, will one day be so accepted that everybody will be doing it. Steroid use will be more common than Botox is now. Every baseball player and pro athlete will be using at least low levels of steroids. As a result, baseball and other sports will be more exciting and entertaining. Human life will be improved, too. We will live longer and better. …We will be able to look good and have strong, fit bodies well into our sixties and beyond. It’s called evolution, and there’s no stopping it.

It is easy to make fun of the evangelistic claims Canseco makes for steroids (what’s called evolution?), but Canseco’s faith in the power of drugs to transform human life for the better is hardly unique, nor is it limited to the arena of sports. In its biographical sections, Juiced tells the Horatio-Alger-esque story of a skinny kid from a working class family of Cuban immigrants in Miami. The first chapter is called “You’ll Never Add Up to Anything,” which is a quote from Canseco’s father, Jose Canseco Sr. The chapter describes what it was like for Jose and his brother, Ozzie, growing up with a man who had “worked so hard to give us a good life in America” and “wanted us to do great things.” Jose and his brother were just average players as teenagers, though, and “average was never acceptable.” Jose’s father told him he was probably going to work at Burger King when he grew up. Jose believed him, comparing himself unfavorably to other players in his little league whom he describes as “automatic” major leaguers.

In Canseco’s case, then, steroids were the answer to a characteristically American question: What can I do to be great? Juiced leaves it a mystery how Canseco managed to get picked in the fifteenth round of the amateur draft in 1982, given what he describes as a fairly paltry skill set (as he tells it, the pick was based on a personal relationship with a Cuban scout and had nothing to do with talent). Still, we may take Canseco at his word that he was not naturally gifted enough to be sure he would “do great things” in America—there is little doubt he saw things that way. Every page of Juiced seethes with Canseco’s insecurity, his self-loathing, and his fear that he will disappoint his father. His sense of inadequacy and fraudulence mars even what should be the high points of his career. When he signs his first professional contract, Canseco describes himself as “too scared to be very happy.” “I had no idea what to expect,” he writes, “and it seemed totally obvious to me that I didn’t belong … I just had no confidence in my abilities.”

After muddling along for two years in the minors, Canseco turned to a combination of liquid testosterone and an injectable anabolic steroid called Deca-Durabolin in the winter preceding the 1985 season. With the aid of an extra 25 pounds of muscle, and an accompanying dose of confidence, the once-marginal prospect shot through the minors and into the major leagues, hitting more than forty home runs at three levels. Beyond leading the A’s to three consecutive World Series appearances, he would evolve into one of the (at that time) rare athletes capable of transcending the world of sports. Canseco appeared shirtless on the covers of fitness and entertainment magazines and in 1991 erupted into the tabloids during a high-profile fling with Madonna. On the field, he appeared oblivious to the fortunes of his team. No matter the score or situation, Canseco swung for the fences on every pitch. His primary responsibility, he says over and over in his book, was to “put on a show” for the fans.

Despite remaining a box office success, Canseco’s act eventually wore thin in Oakland and the slugger was traded to Texas in 1992. To the Rangers, he brought not only his home run swing but also the gospel of steroids. “Not long after I got there, I sat down with Rafael Palmeiro, Juan Gonzalez, and Ivan Rodriguez, three of the Rangers’ young offensive stars, and educated them about steroids,” Canseco recounts. “Soon I was injecting all three of them.” Anyone who still maintains—as many baseball commentators have for years, inexplicably—that steroids are of no real help to a major league hitter should consider the statistical transformation that occurred in the ensuing seasons for Palmeiro, Gonzalez and Rodriguez, all of whom posted career highs in home runs within two years of their sit-down with Canseco. Nor is it any accident that the next fifteen years in baseball constituted the most offensively supercharged period in league history. Between 1966 and 1990, there were only two seasons of fifty or more home runs—by George Foster in 1977 and Cecil Fielder in 1990—in major league baseball. Between 1995 and 2006, there would be 21.

In his detailed account of the era, Juicing the Game, journalist Howard Bryant emphasizes 1996 as the point when the effects of steroids became so obvious that the general public began to take notice. That year, the leadoff hitter for the Baltimore Orioles, Brady Anderson, hit fifty home runs—nine more than he had hit in the previous three seasons combined. He claimed a new legal supplement called creatine, along with an expanded workout regimen, was responsible for his surge in power. Also in 1996, the 33-year-old San Diego Padres third baseman Ken Caminiti bested his career high in home runs by fourteen to win the National League MVP. Caminiti, who died of a drug overdose at the age of 41 in 2004, told Sports Illustrated that his performance that year was aided by steroids he had purchased in Tijuana, Mexico. At the time, Caminiti claimed “at least half” of major league players used steroids. Although he admitted there had been some rough moments—like when his testicles disappeared for nearly three weeks—he defended their decision as well as his own: “If a young player were to ask me what to do,” Caminiti said, “I’m not going to tell him it’s bad. Look at all the money in the game: You have a chance to set your family up, to get your daughter into a better school.”

Two years later, in the memorable summer of ’98, Mark McGwire, then with the Cardinals, and the cheerfully stupid Dominican right fielder for the Cubs, Sammy Sosa, battled into the final weeks of the season to break Roger Maris’s 37-year-old home run record of 61. The country was transfixed as the two sluggers closed in on and then obliterated the record—McGwire finishing with 70 home runs, Sosa with 66. Sosa would hit more than 61 home runs three times between 1998 and 2001, and never lead his league, although as a consolation prize he was invited to Bill Clinton’s presidential box to watch the 1999 State of the Union Address. Meanwhile, in the American League, steroid user Juan Gonzalez won the MVP in 1996 and 1998—then, in 2000, Oakland’s Jason Giambi edged the White Sox’ Thomas for the award. In grand jury hearings held three years later, Giambi confessed to having injected human growth hormones into his stomach and testosterone into his buttocks, as well as to ingesting a female fertility drug called Clomid during his MVP season. 2000 was also the year of a fateful encounter between Canseco and the San Francisco Giants’ Barry Bonds at a celebrity home run contest in Las Vegas. The 35-year-old Bonds, an aging superstar just beginning to familiarize himself with the consolations of performance enhancers, gawked at a shirtless and “shredded” Canseco in the locker room for a long beat, before asking, for everyone to hear, “What the hell have you been doing?” Whether he was motivated by curiosity, sexual attraction, or the desire to embarrass Canseco in public, Bonds was soon doing whatever it was Canseco was doing, and more.

Bonds was baseball royalty. His father, Bobby Bonds, had been a perennial all star gifted with a rare combination of speed and power. His godfather, Willie Mays, was probably the greatest center fielder of all time. Barry spent much of his precocious childhood in major league clubhouses and, as a two-year-old, was said to have shattered a neighbor’s window with a whiffle ball. He was drafted by the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1985 and called up to play the next year after just 115 games in the minor leagues. If Canseco had always doubted his natural ability, Bonds’s challenge was to fulfill what seemed an unlimited promise. Arrogant and notoriously difficult with reporters, he fumed early in his career when he felt that Pittsburgh’s white center fielder, Andy Van Slyke, was receiving excessive attention from the media. In 1998, now with the San Francisco Giants, Bonds became the first hitter ever to steal 400 bases and hit 400 home runs in a career, but the story barely registered as McGwire and Sosa carried on their drug-abetted assault on Maris. Bonds knew he was better than McGwire and Sosa, and resolved, quietly, to prove it.

Up to that point, Bonds’s career had followed a time-honored trajectory mimicking life in miniature. In the early twenties, the athlete ascends to his physical peak but is held back by his lack of experience. In his mid-to-late twenties, he fuses experience and talent for a maximum of competitive success. (Bonds was the best all around player in baseball from 1992 to 1994, posting his [then] career high of 46 home runs at the age of 28, in 1993.) Starting in his early thirties, the athlete undergoes a slow but reliable decline. For a time, his increased knowledge covers for his diminished skills; then the skills diminish to a point where they cannot be compensated for by experience. The year the player’s decline becomes irrefutable is always traumatic, for the fans as well as (we can only assume) for the player. It is often accompanied by injuries resulting from overcompensation and aging. Bonds’s .262 batting average in 1999 was his lowest in a decade, and injuries kept him out of sixty games. But instead of continuing downhill along with the other stars of his generation (Thomas, Ken Griffey Jr., Greg Maddux), Bonds reversed course with the greatest five-year barrage of offense in the history of the game. In 2001, at the age of 36, he broke McGwire’s three-year-old record when he hit 73 home runs amid reports he was on a revolutionary training program that had seen his head grow almost a full hat size. Later, that training program was revealed to have included at least two kinds of anabolic “designer” steroids, and to have been overseen by the infamous BALCO lab in San Francisco, currently under federal investigation for supplying performance enhancing drugs to a motley collection of football players, gold medal-winning sprinters and a significant percentage of the San Francisco Giants World Series roster in 2002.

In the American League, the best player of the early 2000s was the young shortstop Alex Rodriguez. Rodriguez was the epitome of the professional athlete as cross between stage-managed boy band and corporate pitch-man. A surefire star from the time he was promoted to the major leagues at the age of nineteen, his public persona was so carefully crafted that even “spontaneous” displays of emotion on the field appeared calculated. Despite his once-in-a-generation talent, he was embraced by neither teammates nor fans. It did not help when, in 2001, he abandoned a young, promising team in Seattle for a $25 million per year contract proffered by Texas owner Tom Hicks.1 “A-Rod” posted obscene numbers for the last-place Rangers, taking full advantage of a locker room described by his biographer, Selena Roberts, as a “virtual pharmacy for players, full of performance enhancers. There, on the shelves of lockers and sometimes stacked on the floor, sharing space with shoes, were FedEx boxes stuffed with unmarked packages of syringes, steroids and growth hormone.” Eventually, Rodriguez grew impatient with laboring out of the media spotlight and demanded a trade to the Yankees. Although welcomed with open arms by the strippers he would pay handsomely for sex at Scores, the star received a chilly reception from a New York clubhouse led by the respected shortstop Derek Jeter, known for being one of the most accomplished non-steroid users of his era. Behind his back, his new teammates called him “A-Fraud.” The nickname assumed a new significance after it was revealed Rodriguez had tested positive for steroids during a (supposedly) anonymous 2003 trial. Although he claimed he had only taken the drugs for a few months that year, Roberts offers good evidence Rodriguez used for close to a decade and continues injecting growth hormone, for which there is still no test today.

A series of federal investigations, along with the discovery of steroid paraphernalia in several pro locker rooms and in team luggage, compelled baseball to start addressing the issue of steroids in the early 2000s. Steroids had been against league rules since 1971, under the prohibition against prescription medication without a valid prescription; and in 1991, Commissioner Fay Vincent explicitly included steroids in baseball’s drug policy. However, the league was one of the last in the world not to administer a systematic test for performance enhancers. It has become conventional wisdom that the refusal to address steroids more seriously in the 90s was the result of greed on the part of players and owners, each of whom was making too much money to put a stop to it. In fact the owners, led by Vincent’s successor, Bud Selig, made numerous attempts to institute tougher steroid policies beginning in 1994—attempts that were stonewalled by the powerful players’ union, led by Donald Fehr. Fehr framed drug testing as a privacy issue. Additionally, he complained that there was insufficient scientific information about steroids, and that the line between illegal steroids and legal supplements was ill-defined. Polls from the period suggest Fehr resisted testing even after the majority of his union, led by purportedly drug-free stars like Jeter, Thomas and Curt Schilling, had come to favor it. Finally, in the 2002 “basic agreement,” the union consented to the “5 percent plan,” according to which, if more than 5 percent of major league players tested positive for steroids in an anonymous 2003 survey, general testing would be triggered for the following year. More than 7 percent failed the tests, and random testing commenced in 2004.

The program was neither efficient nor harsh enough for the United States Congress. In 2005, amid the fallout from Canseco’s best-selling exposé, the House Government Reform Committee summoned Fehr and Selig, along with Canseco, Sosa, Palmeiro and McGwire, to Washington for a show trial on drugs. The nationally televised “Hearings on Steroids in Baseball” are destined to go down as one of the most shameful spectacles in sports history. Palmeiro, who jabbed his finger at the senators as he denied ever going within spitting distance of a performance-enhancing drug, tested positive for the anabolic steroid Stanozolol less than six months later, before retiring from baseball in disgrace. Sosa pretended not to know English, speaking only through his agent and refusing to answer direct questions. A red-faced McGwire resorted to the punch line that he was “not here to talk about the past.” The next day, Congressman Lacy Clay, a Missouri Democrat, recommended that McGwire’s name be removed from a local highway. The once-beloved slugger disappeared from the game until the winter of 2010, when in a nationally televised interview with Bob Costas he admitted having taken steroids—but only to deal with recurrent back injuries.

The senators spent the second half of the day berating Fehr and Selig. The sport of baseball was “becoming a fraud in the eyes of the American people,” said John McCain, and the Commissioner and union leader were doing nothing to stop it. Fehr and Selig agreed to toughen the penalties for failed tests (from ten to fifty games for a first offense), but Selig initially resisted Congress’s recommendation to initiate an independent investigation of the era. “What we need to do is move forward,” he said. An investigation, led by former congressman and architect of the Northern Ireland peace process, George Mitchell, was launched anyway. The Mitchell Report was released in December of 2007. “For more than a decade there has been widespread illegal use of anabolic steroids and other performance-enhancing substances by players in Major League Baseball,” the report began, going on to identify more than 100 steroid users and implicating every team in the league. But Mitchell agreed with Selig’s judgment that it was not necessary for baseball to take retroactive action. “Knowledge and understanding of the past are essential if the problem is to be dealt with effectively in the future,” wrote Mitchell, “but being chained to the past is not helpful.” His report, he said, should “bring a close to this troubling era in baseball’s history.” Several of the players cited in the report, or subsequently revealed to have taken steroids, would remain in the league and, when they retired, be eligible for baseball’s highest honor, the Hall of Fame.

●

Coverage of the steroid era by sports journalists has resembled a police procedural or, in its more hysterical phases, a murder mystery. The great questions have been who did what and when; almost nothing has been decided about the broader significance of the crime. Some, like The Nation‘s Dave Zirin, insist that steroids are not significant at all, since “muscles cannot be equated with the ability to hit a ball”—an oft-repeated talking point designed to counter a claim no one has ever made. Others have argued that people in all walks of life seek chemical enhancements, or, with Donald Fehr, that steroids are hardly different from legal dietary supplements already rampant in professional athletics. Arguments for the seriousness of steroids, meanwhile, have revolved around the issue of health. In George Mitchell’s 2007 report, steroids stood accused chiefly of posing grave health risks to players and setting a bad example for young athletes, for whom they posed even graver health risks. The Congressional hearings on steroids were carried out under the injunction that “all Americans, especially children, know about the dangers of drug use,” and began with a tearfully told story by a father, Don Hooton, whose high-school-age son had committed suicide after abusing anabolic steroids.

Some confusion on the matter is to be expected. Whether steroids are considered an unforgivable sin or a culturally sanctioned misdemeanor akin to speeding, those inclined to question their significance will find themselves led reliably to a higher question: What is the significance of sports, today, in America? Even limited to professional spectator sports, the question will provoke a startling variety of answers, many of them incompatible. For some, sports are a fun and healthy hobby, for others a deadly serious competition. Sports are often denigrated as a surrogate form of combat in a culture where men no longer have to fight or hunt, although they are just as often held up as a surrogate form of worship in a secular age. They have served as an arena where heroes and villains battle for glory and a stage for political and ethical dramas to be acted out before partisan mobs. However, among those most closely associated with professional sports today—agents, owners, commentators, players—a rough consensus appears to be building around one description of sports. According to that description, professional American sports are, first and foremost, an entertainment business.

Ironically, the description of sport as an entertainment business, so widely embraced today, originated in the form of a lament, issued by social commentators suspicious of the convergence of athletics and capitalism (on the left), or dismayed by free agency—allowing players to sell their services to the highest bidder in a sordid yearly spectacle—and the increasingly “showy” aspects of the games (on the right). In 1979, cultural critic Christopher Lasch announced the end of sport in much the same mode that Hegel, in the nineteenth century, had announced the end of art. Sports would continue to be played and enjoyed by spectators, wrote Lasch in The Culture of Narcissism, but the rituals and conventions that once allowed sports to be truly significant had lost their meaning. It was no longer possible for fans to form long-term bonds with local players; the presentation of the games was corrupted by television and advertising; the players subscribed to an “entertainment ethic” more appropriate to actors and musicians. Such factors conspired, said Lasch, to explode the aura of illusion necessary for sports to elicit genuine enthusiasm. His chapter on “The Degradation of Sport” concludes with the report that “what began as an attempt to invest sport with religious experience … ends with the demystification of sport, the assimilation of sport to show business.”

It took some time for this argument to be appropriated within sports by those who would justify a diverse array of potentially disreputable activities—owners eager to uproot franchises, athletes eager to sell their services to the highest bidders, journalists eager to remain in the good graces of the stars they depend on for access. In the early days of contracts so large they had to call press conferences to explain them, athletes used to perpetrate a predictable white lie: the team that gave them the best chance to win also happened to offer the most money. It was rarely believable, but at least the explanation conceded the importance of a certain mythology—the players cared about winning more than money—thought to be necessary for maintaining the serious fan’s interest in the game. It was discovered at some point, probably by the PR firms and ad agencies assuming an ever-increasing role in the management of athletes’ relations with fans, that such statements played not nearly so well as the assertion that the player was a “businessman,” and that, as anyone with eyes could see, sport was a “business.” What kind of business was sport? One needed only to glance at the crowds: obviously, it was entertainment business.

Such assertions would have seemed superfluous, even to those who made them, had they been meant simply to underline the all-too-evident fact that professional sports now involved money, or an element of performance. What needed to be insisted upon, apparently, was that sports could not be anything more than performance and money—or, stated the other way, that sports were merely performance and money. The word “business” did more than designate the presence of a financial transaction; it described a frame of mind and a statement of purpose. The upshot was that sport should be considered an essentially transactional enterprise, involving profiteers determined to act according to the crudest notions of self-interest and consumers desiring to be harmlessly gratified. Today, if one wants to sound sophisticated, one admits that pro athletes are no different from actors in feature films, paid millions for their ability to entertain large crowds and free to choose where to play based on pay, location and supporting cast. The owners who run pro teams are no different from Hollywood CEOs bent on extracting the highest profit from their product. The journalists who cover pro sports are like entertainment journalists, for whom the content (the games or films or music) is a sideshow not nearly so stimulating as sales figures, TV ratings and the daily gossip concerning ownership, management and stars.

It may sound strange to say that the assumption that sports are an entertainment business lies at the root of the steroid scandal in baseball. More straightforward explanations certainly present themselves—like money, fear and pride—for why professional athletes, over a period of some fifteen years, turned to pills, lotions and injectable fluids capable of offering them an immediate edge over their challengers. But we may speak of the “scandal” of steroids as opposed to the fact. The scandal consists not in the predictable outcome that a percentage of baseball players chose to take performance-enhancing drugs in the 90s, but in the persistence of steroids among the game’s great stars, in the refusal of the players union and the players themselves to take a dignified stance against them, in the reluctance of the league authorities to take the proper punitive action, and in the lack of coherent criticism on the part of sports and culture commentators, filtering down into a potentially self-destructive apathy on the part of the fans. Viewed in this light, the scandal of steroids becomes the scandal of American sports, a once-vibrant cultural form today no longer capable of compelling genuine loyalty, commitment or belief.

There would be little point in speaking seriously of this subject if we could conclude with the cynics that sports really have become indistinguishable from show business. Of course, it is obvious that sports are not just show business—at least that is not what they are to many fans. Beholders of sport in America—apathetic and short-sighted though they may be—have still not been successfully leveled down to “consumers,” nor assimilated to the shrieking enthusiasts characteristic of concerts and film openings. Hope, despair, judgment, indignation and reverence remain elements of spectator sports just as surely as money, exhibitionism and greed. How else to explain the widespread resentment of players perceived as overpaid, or as failing to fulfill their duties as teammates, or as “betraying” one city or another—such resentments being seldom if ever directed against outrageously compensated actors or musicians? Indeed, even in the uneven public response to steroids—in the sporadic anger with which steroid abuse has been met by much of the public, in the refusal of baseball’s veterans committee to vote suspected users into the Hall of Fame, and in the palpable embarrassment of players so far compelled to acknowledge having cheated to succeed—there are signals that reports of the demise of sport may yet be (somewhat) exaggerated.

Lasch himself, at the same time that he worried about the end of sport as a meaningful enterprise, pointed out that sports have shown a capacity to resist the erosion of standards so odious to him in other spheres of society. He cites approvingly Norman Podhoretz’s argument that “the sports public remains more discriminating than the public for the arts,” with excellence, as a criterion of judgment, remaining “relatively uncontroversial.” Thirty years later, in Mediated (2005), the anthropologist Thomas de Zengotita offered a strikingly similar account of sport as an institution simultaneously degraded and privileged. A left-wing variation on many of the themes of Lasch’s earlier work, Mediated chronicles how film, video games and television have transformed—by “mediating”—our contemporary experience. Hardly anything in our culture is more relentlessly mediated than sport, says Zengotita—yet, he reports, his students at Columbia “always balked” at his claim that “real sport was somehow coming to an end”:

And I could see it in their eyes: Derek Jeter means as much to baseball fans today as Ted Williams once meant to me, and in more or less the same way; and the same goes for Zidane as compared to, say, Pelé—in spite of all the marketing contrivances. So I was stuck with this question: if ubiquitous representation can virtualize politics and religion and family life, why should sports be exempt?

My students were supplying the answer all along. … In effect, they kept saying, “Yeah, okay, Jordan looks like a digitized special effect in all the slo-mo replays and commercials, but, during the game itself, he has to make the shot. He really did make that buzzer-beating shot to win against the Jazz in the NBA finals of 1998. That was an incredible performance, a historic moment in the history of the game, and it was real.”

Athletes are performers, Zengotita concedes, but they “are also doing something real—hitting the mark, sinking the putt, catching the ball, crossing the line. Real within the boundaries of the game, of course, but that was always understood.” Zengotita moves on quickly from this insight, soon comparing athletes to pop stars in concert. He emphasizes that popular music and sports—unlike religion and politics—both elicit strong emotions from spectators and produce contemporary icons, like LeBron James and Lady Gaga. However, it is worth noting something Zengotita does not emphasize: his students only call one of them “real.” The one that is real is the game. Within the boundaries of the game, they believe, something true and significant occurs.

The relevant difference between athletes and pop stars, for our purposes, consists in their respective attitudes toward those boundaries, also known as rules. Zengotita’s and Lasch’s analyses converge on the tendency of modern culture to devalue and transgress traditional boundaries, something well-known and approved of by the pop star and her audience. The subtext of every stunt enacted by Lady Gaga is that it is good—not to mention profitable, sexy and fun—to transgress. In contrast, professional athletics are predicated on an agreement between players and fans to respect, even to revere, boundaries. Physically the basketball court, the football stadium, the baseball diamond are bounded, meticulously regulated spaces. First base is exactly 90 feet from home plate, the end zones exactly 100 yards apart. There are rules governing the tucking in of uniforms and the length shorts can be—also against colluding with the opposing team or making a joke of the competition. For spectators there are rules, some of them unwritten, against cheering at inappropriate times or trespassing the invisible wall separating the field from the stands. The popular wisdom that rules are “made to be broken,” shared by Lady Gaga with the innovative CEO and the provocative author, is poisonous to sports. The survival of sports may be said to depend on the maintenance of the boundaries that have protected sports so far, to a certain extent, from the ascendant prejudice against boundaries or what Lasch calls the “attack on illusion.” To put it another way, sports will survive so long as there remains some meaningful distinction between a business and a game.

We are all businessmen most or all of our lives; grace is in the game. The aspiring pro athlete—that is, nearly every male child in America—dreams not of amassing star power or of building himself into a respected brand. Captivated by the pleasure of prevailing over a rival through some combination of natural talent, hard work and strategy, his ambition is to prove he is better than those that come before and with him—to hit harder, to run faster, to win more. Yet he understands almost intuitively that such achievements matter only in the context of the level playing field prescribed by the rules of the game. A six-year-old tends toward a moral clarity regarding rules that escapes our sports journalists, not to mention the professional athletes themselves. Jose Canseco, Mark McGwire and Barry Bonds are complex human beings whose reasons for using steroids may be understandable, even sympathetic. But rules are designed precisely to keep the most common human desires from doing what they will always do if left unchecked: destroy the game. Commissioner Selig, who has been unjustly criticized for failing to prevent the spread of steroids in the 90s, has not been criticized harshly enough for putting “moving on” ahead of ridding the game of cheaters. Every time a known cheater like Alex Rodriguez steps to the plate today, it confirms and hastens the transformation of baseball from a game we can believe in to an entertainment business. Every child knows that the penalty for breaking a game’s rules is to no longer be allowed to play. The game itself is compromised if it does not expel the cheater.

The game is only not compromised if the game is actually something other than a game—say, if the game is a business. The athletes demonstrate a savvy grasp of precisely this logic. The game may once have been a game, say the cheaters, but it is no longer. “Let’s face it, when people come to the ballpark, or watch us on TV, they want to be entertained.” (Canseco) “We’re in the entertainment business.” (Giambi) “The last time I played baseball was in college.” (Bonds)

Such rhetoric, unchallenged by journalists and parroted to a shocking degree by fans, has stood in for reasonable debate regarding the meaning of the steroid scandal in baseball. To go further requires first of all that we get clear about the character of the crimes that have been committed against sports. Contra Canseco, steroids are unhealthy, and their proliferation among professional athletes has likely encouraged use in colleges and high schools. The emphasis on the health risks associated with steroids, however, obscures the fundamental issue—that is, the fundamental issue from what should be the point of view of sports. Risky and, from a certain perspective, unhealthy behavior has always been integral to sports; and in modern sports, we virtually require it from our athletes. There is, for example, increasing evidence that the most popular American sport exposes its participants to debilitating brain injuries. Football players are aware of the risks associated with what they do, and decide to take them, just as many baseball players—like Ken Caminiti, who told Sports Illustrated it was worth the risk despite the fact that his testicles disappeared for nearly three weeks—choose to risk their health by injecting themselves with steroids. The relevant difference has to do with rules rather than health. Even if some steroids were, as Fehr has suggested, only arbitrarily distinguishable from some supplements, this would hardly argue against the need to enforce a distinction. Insofar as there is a game called baseball, any rule may be arbitrary; what matters is that it be followed.

●

Distinctions create the game we know of as baseball. Without rules, there could be no game. We could imagine something—call it an entertainment product—that looked like a game; it might even be called “baseball.”2 Initially, it might be hard to tell the difference between baseball and “baseball”; the difference would nevertheless be detectable, and eventually it would become inescapable, as is the case for even the most hardcore consumers of pro wrestling (or, increasingly, world-class track and field). But do fans really care about the difference between baseball and “baseball”? On the popular sports blog Bleacher Report, Jason Kronewitter recommends we draw conclusions about the public’s attitude from the fact that “this entire ‘scandal’ hasn’t … affected attendance, merchandise sales, or virtually anything that goes along with the game.” Some commentators have gone further, crediting steroids with “saving” baseball after the 1994 players’ strike. Indeed, it is common knowledge that the Steroid Era coincided with a golden age in baseball according to attendance figures and television ratings.

Kronewitter’s instruments betray his bias. To measure the health or sickness of a sport according to ticket and merchandise sales is to concede what it would seem the serious sports fan ought to be at pains to deny: that the bottom line offers the only diagnosis worth having. Professional sports, like any other institutions, can rot from the inside even as they gain new adherents. Popularity and growth are frequently corollaries of corruption rather than proof of its absence or irrelevance—which only raises anew the question of how the most committed fans might register their sense of that corruption.

After all, it is reasonable to presume that the scandal has had the most devastating impact on precisely the most committed fans, the fans least likely to terminate what they nonetheless acknowledge to be a deteriorating relationship with the game. In a 2009 column entitled “Confronting My Worst Nightmare,” ESPN columnist and Red Sox loyalist Bill Simmons (a.k.a. “Sports Guy”) attempted to articulate, from such a fan’s perspective, the emotional consequences of the fog now lying over an entire era. Simmons imagines himself in the future at his beloved Fenway Park, trying to answer his six-year-old son’s questions about the legendary 2004 team that brought Boston its first World Series since 1918, but was led by two stars (Manny Ramirez and David “Big Papi” Ortiz) who later tested positive for steroids:

We look at the 2004 [championship] banner again. I always thought that, for the rest of my life, I would look at that banner and think only good thoughts. Now, there’s a mental asterisk that won’t go away. I wish I could take a pill to shake it from my brain. I see 2004 and 2007, and think of Manny and Papi first and foremost. The modern-day Ruth and Gehrig. One of the great one-two punches in sports history. Were they cheating the whole time? Was Pedro [Martinez] cheating too? That 2004 banner makes me think of these things now. I wish it didn’t, but it does. This makes me sad. This makes me profoundly sad.

The world of sports is still a world where moments that transcend entertainment, historic moments, are possible. But historic—or what Zengotita’s students called real moments—can occur only when the action on the field is trustworthy. In 2004, the Red Sox won the World Series, the next year the team I rooted for, the White Sox, won it; their two fan bases combined had waited 173 long (torturous!) years for a championship. A lingering legacy of the steroid era is that such historic achievements must always be qualified: How many of the team’s stars were cheating? Did they really deserve to win? It may be the case that sports have always embodied a fantasy of transparency on which they can never fully deliver; still, if they are to retain any of their grip on us, we should remain convinced of something irrefutable: a level playing field, a fair battle, a winner and a loser. Only on this conviction can there be a “modern-day Ruth and Gehrig,” or, for that matter, an “incredible performance.”

Buried in a section of the Mitchell Report mostly about the illegality and danger of steroids to physical health, the authors express the concern that performance-enhancing substances raise “questions about the validity of baseball records.” Baseball records can seem a trivial thing, especially when compared to the fragile well-being of America’s young people. In fact the validity of baseball records is tantamount to the validity of baseball, and to the validity of the cultural form we know of as professional sport. Baseball represents an extreme example of what is true in every sport to some extent. Records or numbers allow for comparisons between players and teams. They speak of the arc of a career and of the chances a team has to win; they tell us something about the future and clarify the past. That the 2005 White Sox finished that season with the most wins is not an argument but a fact—recorded, authoritatively, in a sacred book. And records do more than that. Records are the ballast that connects the game’s present to its past. I can compare the best players and teams from my generation to those of my father’s generation because of the record book, and this comparison will mean something, assuming that the game is the same from generation to generation—or basically the same.

The game will change and evolve. Steroids or not, we would expect today’s players to be in better shape than in the 1920s, to have better equipment, and to be drawn from a wider talent pool. Yet the record book offers evidence of intriguing continuities as well. Numbers prove that, as late as 1994, no modern hitter had had a better offensive career than Babe Ruth, the potbellied Yankees slugger rumored to have played many of his games drunk. Until 1998, Roger Maris had held the single-season home run record since 1961, when not one major league stadium housed a weight room. The Cardinals’ Bob Gibson, known for berating teammates who fraternized with opponents, still maintains the modern record for ERA in a season with his microscopic 1.12 mark in 1968. Until 2007, the career record for home runs was held by Hank Aaron, who despite declining skills, amid death threats and racist jeers, blasted a remarkable 40 home runs at the age of 39, in 1973.3 To a baseball fan, there is a beauty and a dignity to such records. Not only astounding natural talent but qualities of character—courage, resourcefulness, endurance—are expressed in them. These things, thank God, are not subject to inflation. A man either surpasses such records or he does not; either way, he receives exactly the credit he deserves.

And so it could be said, until the steroid era, when nearly every offensive record was broken, then broken again, by hitters shot up on Deca, Winstrol and HGH. As fans, we were subjected to a series of now-laughable explanations, which we nevertheless accepted at the time. The parks were smaller; the strike zone was tighter; the baseballs were stringed by a corrupt factory in Caracas. Our faith was such that we could almost explain away the bulging neck muscles and the bloated heads; there were new legal supplements after all, and we seemed to know more every day about how to build muscle in gyms. As in other areas of society, professionalization and the application of scientific methods had perhaps led in baseball to a colossal progress. We believed, or wanted to believe, something else too: that the greatest athletes of our time retained some remnant of responsibility, pride or shame, virtues many of us had learned initially from sports ourselves. How could they break the greatest records while they were cheating? Wouldn’t they buckle under the burden of their transgressions?

Later, we were ridiculed for thinking this way. Or it was said that, since there was so much evidence, we must never have cared very much about steroids. The truth was that many of us deceived ourselves for a time, which is what we do when we love something and we see that thing being ruined by carelessness, greed, laziness, contempt. Integrity as applied to institutions can seem like a nebulous quality until you feel it being compromised. The feeling is so familiar today that we treat it as inevitable, even natural. Distinctions between authenticity and fraudulence in art, politics, and so many other spheres of our shared culture have themselves grown so intricate and confused as to be practically meaningless. There are, however, cultural forms that depend on such a distinction. Sport is one of them. If the boundaries of the games are not respected, attendance and merchandise sales can no more save sports than marketing and technology can destroy them. The decline of sport, like the decline of literature, or of religion, or of journalism, hinges ultimately on a question of will. Do we have the will to protect sports? Are they worth it to us? If the games lose their meaning, what, exactly, will we lose?

●

Viewed from the outside, my relationship with the White Sox was always an abusive one, marred by obsession, dependency and frequent feelings of betrayal. The ridiculousness of the arrangement was not lost on me, which did nothing to free me from it. Despite their relative success in the 90s, the Sox remained the city’s stepchild compared to the wildly popular Cubs, and in adolescence my identification with the team came to be wrapped up with so many other things: performance anxiety in sports; ineptitude with girls; the suspicion that I was different from my peers, possibly special, possibly crazy. Perceived slights, such as the fact that Thomas, statistically the best right-handed hitter since Joe DiMaggio, never received the recognition he deserved (he was overshadowed even in his own city by the steroid-inflated Sammy Sosa), only deepened my devotion to the team, and the few others I knew who rooted for them. I began to understand how people could be religious or patriotic, sentiments I habitually chalked up to childish animal ignorance and fear. I was a child too, it turned out. Night after night I spent three hours in front of a television, in fear and trembling, as grown men I would never meet played a game. My father was right: it was a disease—and there were times I just wished I could be cured.

On the other hand, America is huge. The country is so big that my attachment to it can feel abstract. The city I live in, Chicago, may once have had a distinctive local character palpable to its inhabitants but, as it expands and gentrifies, this character becomes increasingly difficult to pin down. My positive image of the city growing up—an image allowing that there was a city, rather than a collection of individuals simply agreeing in the name of self-interest to share the same ground—came entirely from the teams that were in it. The city showed itself in the way it raised up and disposed of certain players, in the harsh rectitude it visited on lazy stars, and in its profound reverence for winning teams. Occasionally, parts of the city would gather in public to show appreciation for a particular winning team: this was called a parade. In 2005, after the White Sox won the World Series, two million of my neighbors straddled streetlights, hung banners from trees, and cried by the side of the road. It was imperfect—the Steroid Hearings with which the year had begun were still fresh in our minds; and there was already talk about whether the Sox would pay to re-sign their star first baseman—but it gave me the rare sense of being part of something bigger than myself, all of these individual people, Sox fans (there were so many!), celebrating our shared triumph. I had always been baffled by parades; on that day I finally understood what they were for.

Zengotita’s students were right to identify sports as a refuge for the real in a society saturated by artificiality and hype. But that is not their only or ultimate value. Jordan’s climactic buzzer-beater, which the students remember as an irrefutable instance of “real” athletic excellence, was significant for a deeper reason in Chicago: it meant another championship for the Bulls. Transparency enables our experience as fans in America; it does not consummate it—beyond appreciation for individual achievement lies our passion for our teams. Everyone is familiar with the men standing shirtless in the cold with letters painted across their chests, with the overpriced jerseys and hats, with the logoed coffee mugs and comforters, with the inane yelps of bravado, anguish and glee. And behind the scenes there is more: the scouring of newspapers and blogs for information, the countless hours spent listening to half-wits on talk radio and TV, the bathroom breaks to check for up-to-the-second scores on BlackBerries and iPhones. All of it is childish and from a certain perspective pointless, a tremendous squandering of time, energy and resources. Yet beneath these silly rituals rumbles a fragile faith in something big, simple and true: the team of men and their fans united in pursuit of a common goal. The passion for sports in America—I mean the passion for a team playing a sport—seems to lodge itself between the head, the heart and the gut, a soft place where pride converges with dread, love of fairness, and the oft-disparaged desperation for shared roots, for a daily drama that connects us to our fathers as well as our neighbors.

Today, it is said, fans do not invest in sports as they once did; they value celebrity and showmanship over winning and team play; they care little for the rules or purity of the games. Repeated often enough, such pronouncements will one day be true. Their self-fulfilling force, in any case, was never clearer than during the most talked-about “sports” event of last summer, LeBron James’s infamous “Decision.” The shamelessly staged announcement was bad enough; even worse, the way the shell-shocked Cleveland fans were instructed to respond. After all, LeBron was nothing more than a “paid performer,” said the Washington Post’s Howard Kurtz. Why couldn’t Cavs fans understand it was “just business,” asked ESPN’s Scott Van Pelt. Evidently, the intensity and bitterness of the response came as a surprise not only to commentators but also to the young superstar, himself persuaded by the rumor that athletes had evolved into entertainers if not multi-national corporate entities, with no ties to any team, people or place. Shown live images of men and women constructing bonfires out of his jerseys in the streets of Cleveland, one could see the ghost of some grave miscomprehension gather into his eyes, just for a moment, before he remembered the script. The important thing was not to get emotional, said LeBron. And then: “This is a business. And I had seven great years in Cleveland, and I hope the fans understand. And maybe they won’t.”

I grew up in a leafy residential neighborhood less than a mile from Wrigley Field, the home of the Chicago Cubs. All my friends—virtually everyone I knew—were Cubs fans. If there are tics, habits and emotional dependencies common to fans of every sport and franchise, there is also something specific to the community of the faithful surrounding each individual team. Cubs fans are known for being happy, prosperous and good looking. They enjoy drinking, sunbathing, and having fun at the ballpark with their incredibly sexy girlfriends. Disturbingly, at least for those of us who hate them, they appear relatively unfazed by the stunning ineptitude of their team, which has set a standard for ingenuity in managing to avoid winning a World Series since 1908.

Chicago’s other baseball team, the White Sox, played on the South Side, where nobody I knew lived. They played in a ballpark nobody liked, in a neighborhood you had to lock your doors just to drive through. The stands were mostly empty for Sox games; those who did show up were neither attractive nor happy, though they were often drunk. For several years, my father was one of the few adults I knew who would risk subjecting his child to the perils of Sox Park at night—and in 1988, Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf, citing a lack of local support, came within hours of following through on a threat to relocate the team to Florida. All through my childhood, the news that I was a Sox fan was met with gasps of mock surprise or eyebrows quizzically raised: Why root for the Sox?

I rooted for the Sox because it ran in the family, as philandering or alcoholism run in other families. My father—a sober, analytical man, dispassionate to a fault at home and virtually the embodiment of the Protestant ethic at work—was reliably unreasonable on two subjects, Israel being the other. But if talk of U.N. double standards tended to turn him hectoring and shrill, his disquisitions on the Sox were leavened by anxiety, sadness and the withering pessimism we reserve for the things with the potential to hurt us worst. He had grown up on the South Side, back when the Jews still lived down there, and his father had rooted for the Sox. And his father had passed down to him the disease of being a Sox fan (this is the kind of thing he would say), and now he had passed it down selfishly, carelessly, to his son.

He taught me to live and die with every game, every batter, every pitch. I say “taught” although it was inadvertent; he did it, and (to my mother’s horror) I imitated him. Every night of the summer would unfurl the same sentimental drama. The two of us, having kept track of the game from odd angles during dinner, would settle in front of the TV for the final innings. To each other, we spoke exclusively of defeat; in our hearts, we longed frantically for a win. On the nights we were prevented from watching, I remember him returning to the dinner table or the party, his tiny cordless radio tucked into his pocket, with the dreadful news. As we locked eyes, I received my introduction to the idea that there were things in the world that could determine my happiness—things that would simply act on me, and that I could do nothing about. The clipped decrees came like bursts of fate: “Sox up big”; “Sox leading late”; “Sox down but threatening.” And, of course, worst of all: “It’s over. Sox lose.”

What would follow? A swift, surely chemical despair. Some sense of the unfairness of the world, abetted by the feeling that I was suffocating or drowning and with an outward consequence of extreme crabbiness. It was imperative that my mother not speak for at least ten minutes. If I was around strangers, I could occasionally conceal the extremity of my feelings behind a caustic black humor; sometimes I could resist the temptation to lay my head on the table or fling my body to the floor. My politically-minded friends said they felt this way when they woke up to discover George Bush had been re-elected in 2004—I feel it somewhere between 65 and 90 nights each summer, depending on the record of my local team. Immersive video games, television and hard liquor would help in later years; blackness and sleep was best. In the morning, I could begin preparing for the next game.

The Sox lost a lot all through the 1980s; then, just as I became old enough to follow them conscientiously as a fan, they began to win more than they lost. A new ballpark and a series of strong draft picks—Robin Ventura, Alex Fernandez, Frank Thomas—catapulted the team to prominence in the American League Central, where they competed for division titles nearly every year. I will remember the 90s in baseball for the resurgence of the Sox, the return of their fan base from whatever distant suburbs they had disappeared to, and the team’s two forays into the playoffs, in 1993 and 2000 (even though both culminated in quick, soul-crushing defeats). Also for the ascendency of Thomas, a mass of a man, formerly a tight end at Auburn, soon known on the South Side as the “Big Hurt” for the almost unprecedented harm he was capable of inflicting on a baseball. Thomas’s at bats, in those days, were events—and I watched closely. It seemed the secret to life might lurk in the way he lifted his back heel just slightly off the ground as he made contact, or in the discernment he showed holding back his bat on pitches destined to veer millimeters outside the zone. My father, always sensitive to the importance of sample size, conceded eventually that we were in the presence of genius. The evidence, to me at least, seemed incontrovertible.

I was lucky. My innocence as a fan coincided fortuitously with that of the sport. For it is already clear that the decade will be remembered by history for very different sorts of reasons. According to a raft of recent articles, books and documentaries—including Ken Burns’s exhaustive chronicle, The Tenth Inning—the real drama during those years unfolded off the field, behind closed doors, in workout facilities and pharmaceutical labs and doctors’ offices. Some players—probably a lot of players—cheated; many of the most impressive performances were made possible by drugs. If we could have guessed about such things at the time, now we know too much to ignore them. Whatever we may wish to be the case, history will remember the 90s in baseball as the beginning of the Steroid Era.

●

Stories about steroids in baseball are often headlined lasciviously—steroids was an “orgy”; the whole league was “juiced”—although the progression itself was predictable, even anodyne. As the action on the field grew more extreme, the players transformed themselves into veritable drones of efficiency. They did so in conjunction with the arrival of a new generation of owners, like Tom Hicks in Texas and John Henry in Boston, who had migrated to the sport from the corporate world. Expecting returns commensurate with their sizable investments, such owners were impatient with conduct detrimental to performance on the field. Steroids were the opposite of all earlier drugs in this respect. Instead of distracting players from their job, they helped them perform at what had previously been considered impossibly high levels. The juiciest bits from the steroid memoirs involve grown men disappearing into bathroom stalls to shoot each other in the buttocks with a needle. The visible consequences included acne, bloating, shrunken testicles, and hundreds upon hundreds of home runs.

It was progress, said many. Throughout the 90s, players would recall how much worse things had been before, when, rather than lifting weights and rubbing themselves with bionic lotions, they had snorted cocaine, driven drunk, and banged groupies in the bullpen. Mets clubhouse assistant Kirk Radomski, a key witness for the government sponsored Mitchell Report on steroids in 2007, recalls an infamous New York Mets clubhouse teeming with recreational drugs and X-rated practical jokes. Indeed, the mid-80s Mets, led by Darryl Strawberry, Doc Gooden and David Cone, defined what could one day be known as the performance de-hancing drug era in baseball. The first drug test that Radomski describes in his memoir, Bases Loaded, is Gooden’s—and it was not for steroids.

Gooden, a toothpick-skinny pitcher from Florida, had burst on the scene in 1984, winning 17 games and striking out a staggering 276 hitters at the age of nineteen. According to Radomski, Gooden never took steroids or even lifted weights, which may be one reason he failed to fulfill his prodigious promise, unlike the second best young pitcher in baseball during those years, the Boston Red Sox’ Roger Clemens (who did both). Gooden had other problems, though. In 1986, he was arrested for fighting with police in Tampa. The next year he was institutionalized after testing positive for cocaine during spring training. He would struggle his whole career with substance abuse, entering rehabilitation facilities several times and being arrested for drunk driving twice. Radomski claims he helped Gooden cheat on two urine tests in 1988. In 1991, Gooden was accused along with two teammates of rape (the charges were later dropped); in 2005, he was convicted of a misdemeanor after punching his girlfriend.

The young pitcher became a symbol for his era. Drugs, alcohol and spousal abuse were public relations nightmares for the sport throughout the 80s. Steroids, traditionally associated with track and field and football, only became popular in baseball toward the end of the decade. The earliest case Radomski recalls from his days with the Mets was that of outfielder Lenny Dykstra, who arrived at spring training having added 35 pounds of muscle in 1990. Dykstra was a gritty 27-year-old slap hitter—he’d earned the nickname “Nails” for his supposed toughness—coming off an abysmal 1989 season. In 1990, he posted career highs in nearly every offensive category despite tailing off in the second half due to what Radomski diagnoses as an improperly spaced “cycling” technique with his drugs.

Baseball, it had always been thought, was a sport requiring agility, finesse and stamina. The conventional wisdom was that excessive weight lifting and supplements slowed players down and exposed them to injury. Such assumptions had begun to be revised a few years earlier based on developments in the Bay Area, where, in 1987, the Oakland A’s Bunyonesque first baseman Mark McGwire set a rookie record with 49 home runs. McGwire joined outfielder Jose Canseco to form an imposing duo in the middle of the A’s lineup soon known, based on their body-builder physiques and the homoerotic forearm bump they invented for celebrating long balls, as the “Bash Brothers.” The A’s reached the World Series three straight years from 1988-1990, winning in 1989. In 1988, Canseco won the league’s Most Valuable Player (MVP) award after becoming the first player ever to hit forty home runs and steal forty bases in the same season. Taunted by Red Sox fans in the playoffs for being a steroid cheat, the slugger responded with a smile and a gaudily flexed bicep. The next year, he was rewarded with the richest contract in major league history.

Canseco’s memoir, Juiced, is the most revealing book yet written about steroids. This is because it is the only book whose author is unabashedly pro-steroids. Canseco never pretends his success was the result of hard work, or that steroids were merely a hedge against injuries (both assertions were made by McGwire after he admitted using in 2010). Rather, steroids were “the key to it all”; combined with growth hormone, their effect was “just incredible.” In the future, Canseco is certain that everyone will use:

It is easy to make fun of the evangelistic claims Canseco makes for steroids (what’s called evolution?), but Canseco’s faith in the power of drugs to transform human life for the better is hardly unique, nor is it limited to the arena of sports. In its biographical sections, Juiced tells the Horatio-Alger-esque story of a skinny kid from a working class family of Cuban immigrants in Miami. The first chapter is called “You’ll Never Add Up to Anything,” which is a quote from Canseco’s father, Jose Canseco Sr. The chapter describes what it was like for Jose and his brother, Ozzie, growing up with a man who had “worked so hard to give us a good life in America” and “wanted us to do great things.” Jose and his brother were just average players as teenagers, though, and “average was never acceptable.” Jose’s father told him he was probably going to work at Burger King when he grew up. Jose believed him, comparing himself unfavorably to other players in his little league whom he describes as “automatic” major leaguers.

In Canseco’s case, then, steroids were the answer to a characteristically American question: What can I do to be great? Juiced leaves it a mystery how Canseco managed to get picked in the fifteenth round of the amateur draft in 1982, given what he describes as a fairly paltry skill set (as he tells it, the pick was based on a personal relationship with a Cuban scout and had nothing to do with talent). Still, we may take Canseco at his word that he was not naturally gifted enough to be sure he would “do great things” in America—there is little doubt he saw things that way. Every page of Juiced seethes with Canseco’s insecurity, his self-loathing, and his fear that he will disappoint his father. His sense of inadequacy and fraudulence mars even what should be the high points of his career. When he signs his first professional contract, Canseco describes himself as “too scared to be very happy.” “I had no idea what to expect,” he writes, “and it seemed totally obvious to me that I didn’t belong … I just had no confidence in my abilities.”

After muddling along for two years in the minors, Canseco turned to a combination of liquid testosterone and an injectable anabolic steroid called Deca-Durabolin in the winter preceding the 1985 season. With the aid of an extra 25 pounds of muscle, and an accompanying dose of confidence, the once-marginal prospect shot through the minors and into the major leagues, hitting more than forty home runs at three levels. Beyond leading the A’s to three consecutive World Series appearances, he would evolve into one of the (at that time) rare athletes capable of transcending the world of sports. Canseco appeared shirtless on the covers of fitness and entertainment magazines and in 1991 erupted into the tabloids during a high-profile fling with Madonna. On the field, he appeared oblivious to the fortunes of his team. No matter the score or situation, Canseco swung for the fences on every pitch. His primary responsibility, he says over and over in his book, was to “put on a show” for the fans.

Despite remaining a box office success, Canseco’s act eventually wore thin in Oakland and the slugger was traded to Texas in 1992. To the Rangers, he brought not only his home run swing but also the gospel of steroids. “Not long after I got there, I sat down with Rafael Palmeiro, Juan Gonzalez, and Ivan Rodriguez, three of the Rangers’ young offensive stars, and educated them about steroids,” Canseco recounts. “Soon I was injecting all three of them.” Anyone who still maintains—as many baseball commentators have for years, inexplicably—that steroids are of no real help to a major league hitter should consider the statistical transformation that occurred in the ensuing seasons for Palmeiro, Gonzalez and Rodriguez, all of whom posted career highs in home runs within two years of their sit-down with Canseco. Nor is it any accident that the next fifteen years in baseball constituted the most offensively supercharged period in league history. Between 1966 and 1990, there were only two seasons of fifty or more home runs—by George Foster in 1977 and Cecil Fielder in 1990—in major league baseball. Between 1995 and 2006, there would be 21.

In his detailed account of the era, Juicing the Game, journalist Howard Bryant emphasizes 1996 as the point when the effects of steroids became so obvious that the general public began to take notice. That year, the leadoff hitter for the Baltimore Orioles, Brady Anderson, hit fifty home runs—nine more than he had hit in the previous three seasons combined. He claimed a new legal supplement called creatine, along with an expanded workout regimen, was responsible for his surge in power. Also in 1996, the 33-year-old San Diego Padres third baseman Ken Caminiti bested his career high in home runs by fourteen to win the National League MVP. Caminiti, who died of a drug overdose at the age of 41 in 2004, told Sports Illustrated that his performance that year was aided by steroids he had purchased in Tijuana, Mexico. At the time, Caminiti claimed “at least half” of major league players used steroids. Although he admitted there had been some rough moments—like when his testicles disappeared for nearly three weeks—he defended their decision as well as his own: “If a young player were to ask me what to do,” Caminiti said, “I’m not going to tell him it’s bad. Look at all the money in the game: You have a chance to set your family up, to get your daughter into a better school.”