In 1989 Francis Fukuyama prophesied “the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” Less than thirty years later, liberal democracy, we are told, is in crisis. The rumblings of political discontent in the aftermath of the Great Recession have erupted into Brexit, Donald Trump, and impressive gains for Euroskeptic, conservative and populist parties across Europe—especially in Hungary, where Victor Orban’s conservative-nationalist party Fidesz was voted into office in 2010, and in Poland with the rise of the Christian national-conservative Law and Justice. In response, intellectual commentators in Europe and America have declared an imperative to defend and restore the liberal order.

But what if the celebrated passage from communism to liberal democracy was not the momentous advance that we often take it to be? What if liberal democracy is, at its core, an ideology with more links to communism than is commonly supposed? In that case the present crisis might offer an opportunity as well as a risk.

Such possibilities are raised in The Demon in Democracy: Totalitarian Temptations in Free Societies, by Ryszard Legutko, a Polish professor of philosophy and member of the European Parliament. Legutko, whose influence has recently grown among conservatives in Europe and the United States, argues that the nature and flaws of liberal democracy and communism are much more similar than most like to think. Above all they are similar in the way their underlying logic leads to the strengthening of what is “common” or base in man at the expense of what is potentially great and noble in him.

The premise of The Demon in Democracy is not particularly original: comparing liberals to communists and conservatives to fascists, Obama to Lenin and Trump to Hitler, is a tactic favored by today’s hyperbolic political commentariat, which evinces a very human tendency to make too much of a similarity, however slight, that suits one’s purposes. Legutko’s highly polemical prose may give the impression that his book is another contribution to this genre, but The Demon in Democracy offers something different. It is distinguished not only by Legutko’s philosophical breadth, but also by his ability to weave together political criticism with personal testimony of his time in communist and then liberal-democratic Poland.

The fall of communism in Eastern Europe, Legutko recalls, was greeted as a chance to restore the destroyed social fabric and once again pursue “noble goals.” Instead, it resulted in a new “wave of barbarism,” as the new society, under the “ideological spell” of liberal democracy, took aim at many of the same “social forms, types of conduct, norms, and practices” as had been suppressed under communism. The resulting culture was ideological, sterile and vulgar: “loutish manners and coarse language” prevailed as “the rules of civility” were derided and “art, ideas, and education” were reduced to what is comfortable and simple rather than being celebrated for their “elevating power.” Man himself, freed by the liberal-democratic ethos from “the major obligations that made his life difficult,” was reduced to his “common qualities.”

The argument of The Demon in Democracy is unlikely to sway either academics or partisans of the liberal-democratic order, and it is doubtful that it is intended to. Legutko, rather, speaks first to those who remember communism and whose judgment of liberal democracy might change upon seeing its similarity to the ideology they abhor, and second to those who remain deeply discontented with the present order and find themselves unattached to its pieties. In such readers The Demon in Democracy aims to arouse regret for the path that has been taken, as well as some hope that an alternative may yet remain open.

●

Legutko’s anti-liberal and anti-communist critique, which places a high value on Christian and classical culture while lamenting a declining West, bears resemblance to the work of interwar European conservatives and even to that of certain American authors such as Russell Kirk. But Legutko has the advantage of a 21st-century vantage point on the history of liberalism and communism, not to mention that of fascism. Writing from Poland, he draws on the country’s distinctive experience with the three dominant ideologies of the twentieth century. Born to parents who experienced the Nazi invasion, Legutko has lived through communism, through the transition to liberal democracy, through the early years of independence, and now through the era of the European Union.

Legutko is of course aware of the differences between liberal democracy—the combination of liberalism and democracy—and communism. He acknowledges that the violent coercion and blatant propaganda typical in communist countries are largely off limits in a regime professing its commitment to freedom of speech and conscience. Unlike in communism, there are no “official guardians” of doctrine in liberal democracy. And yet, according to Legutko, at their core the two ideologies are similar enough for it to be foolish to oppose one but embrace the other. In particular, they share three fundamental features: “anthropological minimalism,” a progressive view of history, and belief in the idea of equality.

First, both communism and liberal democracy reject the teleological conception of human nature. Neither takes seriously the classical idea that human beings have a discernible “telos” or purpose. This is one marker of their joint origin in modernity. As the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre points out in After Virtue, the teleological view of man as having “an essence which defines his true end” has been largely rejected by modern thinkers, while the very notion of man’s having any essence at all has come to be regarded as dubious.1 Legutko argues that this anthropological conception of human nature is tied to the Enlightenment repudiation of the “excessive demands” imposed by aristocratic and religious ideals in the Middle Ages and antiquity. Because the ends or objectives of individuals can no longer be judged with reference to a human nature or essence, there can be no justification for limiting our pursuit of pleasure, utility and comfort. Liberal democracy and communism thus “legitimize the lowering of human aspirations”; indeed, as Legutko notes, the word “common” ceases to be a word of disapproval.

The second similarity between liberal democracy and communism is that both see history as a slow progress towards the current order. In modernity, Legutko writes, the past is no longer an object of reverence, but rather something that should be treated with “sympathy mixed with condescension.” The prejudice against the old is encapsulated in typical expressions of condemnation such as when we call things “medieval,” “backward” or “anachronistic,” as well as in the use of “modern” as a term of praise.

The communist claim to uncover historical laws necessitating the overthrow of capitalism is well known. Liberal democracy has nothing equivalent to an official, grand theory of history. But, Legutko notes, it has an implicit narrative to make sense of the past. The past is the history of struggle for freedom and against oppressors—“the struggle between Liberty and Authority” as John Stuart Mill writes—with liberal democracy as “the final realization of the eternal desires of mankind, particularly those of freedom and the rule of the people.” The enemy takes on different forms—monarchy, aristocracy, the church, and later fascism, communism, imperialism, nationalism, and so on—but each is an instance of the basic impulse of anti-liberal and anti-democratic tyranny.

This progressive view of history explains how a theorist like Fukuyama could believe that the triumph of liberal democracy would signal the “end” of historical or political development. It also explains why, as Legutko puts it, opposition to liberal democracy is so frequently seen to signify not just political disagreement but a dangerous attempt to preserve “the remnants of old authoritarianisms.” According to liberal orthodoxy, such an attempt is irrational, like “a desire for a grown man to return to his mother’s womb”—one that should be speedily relegated to “the dustbin of history”2 and replaced with 21st-century standards.

The third similarity is that both liberal democracy and communism aim to fashion humans and communities according to the demands of equality. According to Legutko, equality defines the West’s modern identity and its image of the future; it is given “a status of the highest value and made a regulating principle.” Humans are seen as primevally equal, and the job of society is to make them equal again. The liberal democratic commitment to equality first manifests itself in equality before the law. But as democratization of society increases and the idea of universal equality takes root, the focus shifts—first onto the persistence of inequality in “people’s customs and habits” and then onto the way people think about and conceptualize the world. Since traditional communities, social relationships, customs and practices tend to be characterized by inequality and hierarchy, they need to be uprooted and remade; and since language shapes people’s thoughts, a “Newspeak” emerges with concepts “so value-loaded that they permit no discussion.”

The final consequence of these egalitarian efforts, Legutko argues, is that all aspects of society are politicized. The constant urging to “change and reform”—on university campuses, in the media, now even by big businesses—and the inevitable failure of the political process to turn our ever greater hopes into reality, is taken to signal the need for ever greater political exertions. The successive battles for freedom end up destroying national and religious particularities developed over centuries, replacing them with new categories—“feminist,” “environmentalist,” “queer”—which lack any organic history or set of shared practices. The outcome is not the flourishing of many different cultures, but rather the profusion of political “identities,” which all share allegiance to the homogeneous liberal democratic culture and politics that made them possible.

Legutko thinks there are many things to learn, and to learn to condemn, from this comparison of liberal democracy and communism, these two “greatest hopes of mankind.” But two in particular should be emphasized. First, Legutko finds the hostility of liberal democracy to Christianity particularly troublesome. The final chapter of The Demon in Democracy is devoted to explaining how today’s liberal democracies tolerate Christianity only insofar as it modernizes and thus becomes subservient to the dominant ideas and institutions—a demand to which some Christians have succumbed. In such a case, Christianity is deprived of any meaningful role in society and, eventually, ceases to function as “a viable alternative to the tediousness of liberal-democratic anthropology.”

Second, Legutko sees liberal democracy as a force driving the decline of the West and its people. Anthropological minimalism and the passion for equality have reduced standards and aspirations, and though it remains capable of economic and technological success, Legutko believes the West’s rejection of its own tradition is connected to its ongoing cultural and economic deterioration. Christian and classical culture, once revered as essential for elevating humanity, are now treated by many in the West as retrograde elements of a premodern, nondemocratic, and nonliberal past. Meanwhile, what is truly valuable in the West has been reinterpreted to lie in liberal democracy, the achievement that redeems the madness that came before.

●

Does Legutko offer a different way forward? It is important to note that The Demon in Democracy offers little comfort to Anglophone conservatives who remain committed to a more genuine—more democratic and free—liberal democracy. Despite attempts to claim Legutko as one of their own, most notably in the foreword to The Demon in Democracy, by the National Review’s John O’Sullivan, Legutko is not opposed simply to the bureaucratic, political or media elites who supposedly hinder the flourishing of a “majoritarian democracy resting on constitutional liberal guarantees.” Nor is he a “populist,” whatever exactly that term really means. A quick glance at the original title of his book—“Triumf czlowieka pospolitego” or “Triumph of the Common Man”—is instructive: for Legutko, the triumph of what is common is the problem, not the solution. Handing power over to the “real people … ordinary people … decent people” lauded by Nigel Farage will hardly suffice.

If The Demon in Democracy offers no road map for politics, in subsequent interviews Legutko has been more explicit about how his ideas might inform contemporary political conservatism. Conservatives, he suggests, should embrace the West as the realm of Christian and classical civilization, a notion rejected not only by today’s left but also by those on the right who are all too eager to claim that they, too, are “open, pluralistic, tolerant and inclusive.” Though the “Christian and Classical roots of this culture, classical metaphysics and anthropology, beauty and virtue, a sense of decorum, liberal education, [and] family” are all under pressure, they have not yet been lost, and Legutko does not think it is too late to recognize their importance for the cultivation of the Western mind. Until conservatives realize that these—rather than, say, tax cuts, economic growth and opposition to media bias—are the things they stand for, they can expect little to change.

What might this recognition entail in terms of pragmatic political action? For Legutko, particularities of time, place and national character are important; there is no reason to believe the same arrangements should rule everywhere. Nevertheless, his own career in politics offers some indication of the practical steps he has in mind. Legutko has served in the Polish Senate, as the education minister, and as the Secretary of State in the Chancellery of President Lech Kaczyński—and in 2009 he was elected to the European Parliament where he is currently the co-chairman of the Euroskeptic European Conservatives and Reformists political group (home also to the British Conservative Party). Central to both Law and Justice and Legutko is the battle against the political project of the contemporary E.U.—the “ever closer union”—on behalf of an alternative, conservative, politics.

Law and Justice has close ties to the Catholic church, and its platform is socially conservative and solidarist. The party, established in 2001 after a split in the political arm of Solidarity—the Catholic-associated trade union behind the anti-communist resistance of the Eighties—emphasizes law and order, patriotism and the de-communization of the Polish state and society; supports intervention in the economy to promote social goals; and opposes E.U. integration insofar as it is political rather than economic. Having led the government from 2005 to 2007, the party returned to power after winning elections in 2015. Over time it has consolidated Poland’s political right by taking over support from various nationalist and Christian democratic groups: its base tends to be rural, working class, poor and old.

Overall, the politics of Law and Justice has proved to be popular domestically, despite spirited opposition from more liberal Poles. As Remi Adekoya writes in Foreign Affairs, the party “has responded to two of the major issues of contemporary European politics—identity and inequality—by effectively combining social conservatism and nationalism with welfarism.” Expectedly, it has met with much disfavor in Western Europe, and Legutko’s tenure in the European Parliament has seen a souring of Poland’s relationship with the E.U. In the past two years, Brussels has accused Poland of violating the rule of law and democracy, with the European Commission threatening sanctions and the removal of E.U. voting rights. The conflict has primarily centered on a series of proposed reforms to Poland’s judicial system. (Among them, in the name of restoring checks and balances, Poland wants to give its legislature a partial say in the appointment of judges. The E.U. has claimed the changes undermine judicial impartiality.) But Poland’s refusal to accept E.U. refugee quotas (even as it has welcomed Ukrainians displaced by the war in Donbass), and its conservative stance on moral and cultural issues, such as abortion, have also been sticking points.

In response to E.U. demands, the Polish government has asserted the right of member states to decide on such internal issues in accordance with their national traditions. Poland is a heavily Catholic and, since World War II, culturally and ethnically homogeneous country. Pew Research polling from 2016 shows that over 70 percent of Poles think being Catholic is important for being Polish, and 95 percent think the same about sharing national customs and traditions. (According to other surveys, three quarters of Poles oppose accepting any asylum-seekers from the Middle East or Africa, and, remarkably, even though nine in ten support E.U. membership, over half would refuse Muslim migrants even at the cost of leaving the E.U.)

Many Polish politicians thus find themselves on a collision course with Brussels as it aims to create a Federal Europe. The conflict between the E.U.—which Legutko describes as displaying “the order and the spirit of liberal democracy in its most degenerate version”—and Poland shows why, for Legutko, any conservative awakening must begin with individual nation-states.

Reflecting on Poland before the fall of communism, Legutko writes that, despite common narratives today, the strongest impetus for resistance had “little to with liberal democracy.” Rather, it lay in “patriotism, a reawakened eternal desire for truth and justice, loyalty to the imponderables of the national tradition, and—a factor of paramount importance—religion.” The heroes of yesteryear stood for the very things modern liberal democracy is hostile towards—the nation, tradition and religion. Recovering these as part of a new way of thinking and speaking about society, politics, the common good and the future is key for Legutko if we are to rise up from our present mediocrity.

●

Still, a question persists: What is the best political arrangement to overcome the commonness Legutko laments? Legutko’s emphasis on moving beyond liberal democracy and its stated emphasis on pluralism, equality and individual freedom will no doubt provoke some skepticism: Is Legutko’s conservative criticism anything more than a call to return to authoritarianism, religious intolerance and other forms of bigotry? Perhaps the most difficult challenge of The Demon in Democracy is its insistence on standards beyond freedom and democracy, on the possibility of elevating man and revitalizing the West while at the same time preserving our basic liberties.

As is typical of resolute critics, Legutko is much clearer on the nature of the problems than on where he hopes for us to end up. But The Demon in Democracy does resuscitate a classical notion that our times have forgotten: the mixed regime. Legutko notes that most governments are defective because they are one-sided, overemphasizing the monarchic, the oligarchic or the democratic element. The solution is to mix the three types and craft the regime accordingly, ensuring “democratic representativeness but at the same time some oligarchic-aristocratic institutions … [to] preserve a form of elitism as well as some form of monarchy guaranteeing the efficiency of governance.” This idea, Legutko notes, is at the core of the republican tradition and can be seen in the philosophy behind the U.S. Constitution, which, reflecting the Founders’ aversion to mob rule, contains many limitations on democracy.

What exactly a mixed regime would look like today, when “democratic” is almost universally considered a term of praise, is an open question. But Legutko implies that some such arrangement would help prevent the descent into democratic commonness by tempering the tendencies of democracy and liberalism. As a regime it would be more internally diverse and less restrictive than the current order, incorporating some undemocratic institutions and making room for nondemocratic sensibilities. It would thus be more likely to leave space for communities to flourish, tradition to persist, and religion to emerge from the margins—all helping to sustain the sense that humanity can sometimes transcend the vulgar and the common.

Though he extols certain virtues and has a clear conception of the good, Legutko does not claim to have all the answers—and he maintains openness about the future. His description of his experience in Poland is again telling in this regard. The liberation of Eastern Europe held the great promise of an open future, he believed: with the fall of the Berlin Wall, it seemed the newly independent countries would each have a chance to develop a political system and society best suited to their heritage, their national particularities and the pursuit of the good. Instead, the promise quickly evaporated as nations leaped into Western liberal democracy, initiating a new era of conformism. Beneath the vigorous ire of Legutko’s writing one can sense a faint nostalgia of what could have been but was not—and a faint hope for what might be.

And yet The Demon in Democracy is not an optimistic book. Though it is hard to know the outlook for Eastern Europe or the West, Legutko parts on an apprehensive note. It seems likely, he writes, that “human history will add some new chapters” after “the current view of man spends itself and is considered inadequate.” But he acknowledges another possibility. Perhaps modernity has “divulged … a basic truth about modern man,” with further fundamental changes in human history unlikely; “except changes for the worse.” If so, “it will be a final confirmation that [man’s] mediocrity is inveterate.” The question, then, is how it could ever have been otherwise.

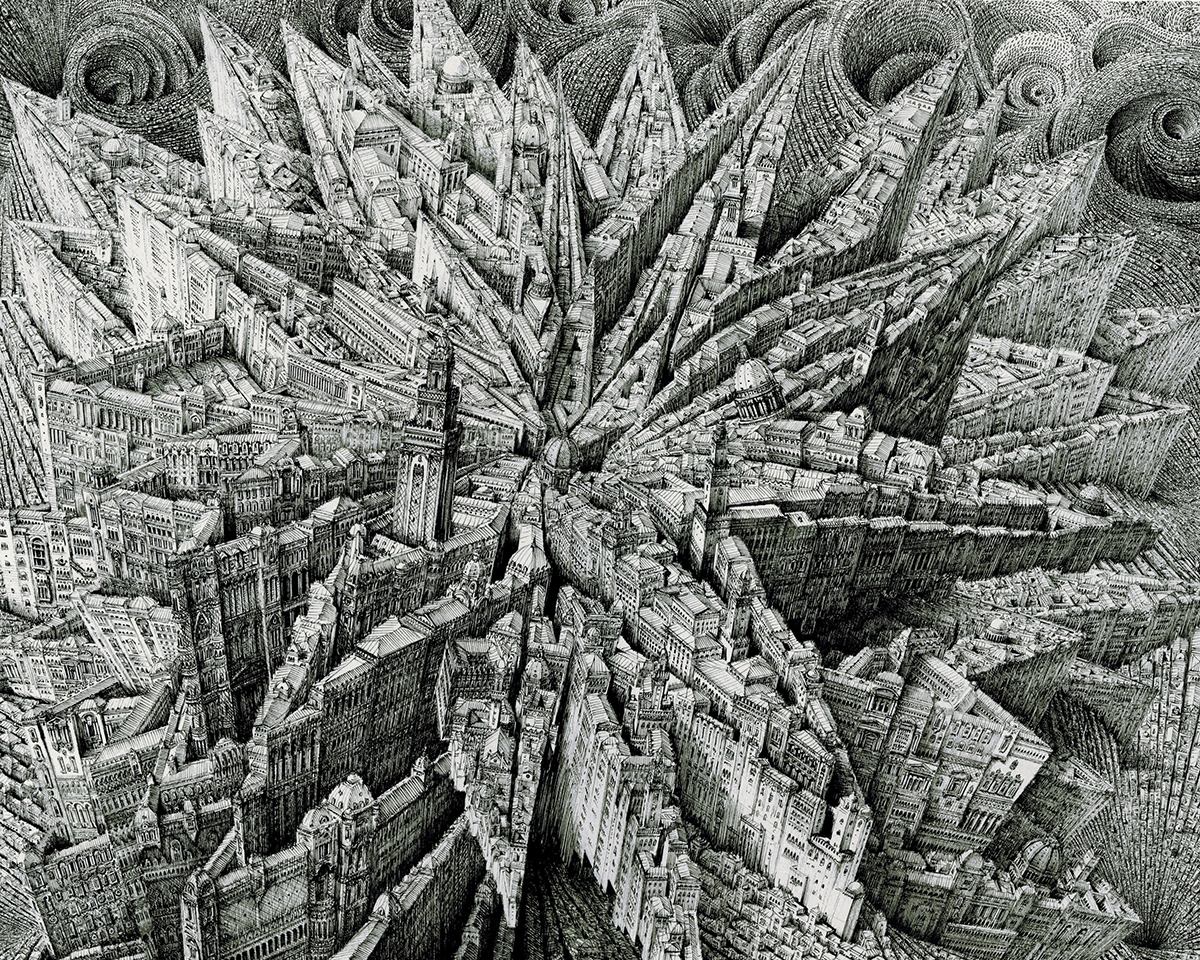

Art credit: Benjamin Sack

In 1989 Francis Fukuyama prophesied “the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” Less than thirty years later, liberal democracy, we are told, is in crisis. The rumblings of political discontent in the aftermath of the Great Recession have erupted into Brexit, Donald Trump, and impressive gains for Euroskeptic, conservative and populist parties across Europe—especially in Hungary, where Victor Orban’s conservative-nationalist party Fidesz was voted into office in 2010, and in Poland with the rise of the Christian national-conservative Law and Justice. In response, intellectual commentators in Europe and America have declared an imperative to defend and restore the liberal order.

But what if the celebrated passage from communism to liberal democracy was not the momentous advance that we often take it to be? What if liberal democracy is, at its core, an ideology with more links to communism than is commonly supposed? In that case the present crisis might offer an opportunity as well as a risk.

Such possibilities are raised in The Demon in Democracy: Totalitarian Temptations in Free Societies, by Ryszard Legutko, a Polish professor of philosophy and member of the European Parliament. Legutko, whose influence has recently grown among conservatives in Europe and the United States, argues that the nature and flaws of liberal democracy and communism are much more similar than most like to think. Above all they are similar in the way their underlying logic leads to the strengthening of what is “common” or base in man at the expense of what is potentially great and noble in him.

The premise of The Demon in Democracy is not particularly original: comparing liberals to communists and conservatives to fascists, Obama to Lenin and Trump to Hitler, is a tactic favored by today’s hyperbolic political commentariat, which evinces a very human tendency to make too much of a similarity, however slight, that suits one’s purposes. Legutko’s highly polemical prose may give the impression that his book is another contribution to this genre, but The Demon in Democracy offers something different. It is distinguished not only by Legutko’s philosophical breadth, but also by his ability to weave together political criticism with personal testimony of his time in communist and then liberal-democratic Poland.

The fall of communism in Eastern Europe, Legutko recalls, was greeted as a chance to restore the destroyed social fabric and once again pursue “noble goals.” Instead, it resulted in a new “wave of barbarism,” as the new society, under the “ideological spell” of liberal democracy, took aim at many of the same “social forms, types of conduct, norms, and practices” as had been suppressed under communism. The resulting culture was ideological, sterile and vulgar: “loutish manners and coarse language” prevailed as “the rules of civility” were derided and “art, ideas, and education” were reduced to what is comfortable and simple rather than being celebrated for their “elevating power.” Man himself, freed by the liberal-democratic ethos from “the major obligations that made his life difficult,” was reduced to his “common qualities.”

The argument of The Demon in Democracy is unlikely to sway either academics or partisans of the liberal-democratic order, and it is doubtful that it is intended to. Legutko, rather, speaks first to those who remember communism and whose judgment of liberal democracy might change upon seeing its similarity to the ideology they abhor, and second to those who remain deeply discontented with the present order and find themselves unattached to its pieties. In such readers The Demon in Democracy aims to arouse regret for the path that has been taken, as well as some hope that an alternative may yet remain open.

●

Legutko’s anti-liberal and anti-communist critique, which places a high value on Christian and classical culture while lamenting a declining West, bears resemblance to the work of interwar European conservatives and even to that of certain American authors such as Russell Kirk. But Legutko has the advantage of a 21st-century vantage point on the history of liberalism and communism, not to mention that of fascism. Writing from Poland, he draws on the country’s distinctive experience with the three dominant ideologies of the twentieth century. Born to parents who experienced the Nazi invasion, Legutko has lived through communism, through the transition to liberal democracy, through the early years of independence, and now through the era of the European Union.

Legutko is of course aware of the differences between liberal democracy—the combination of liberalism and democracy—and communism. He acknowledges that the violent coercion and blatant propaganda typical in communist countries are largely off limits in a regime professing its commitment to freedom of speech and conscience. Unlike in communism, there are no “official guardians” of doctrine in liberal democracy. And yet, according to Legutko, at their core the two ideologies are similar enough for it to be foolish to oppose one but embrace the other. In particular, they share three fundamental features: “anthropological minimalism,” a progressive view of history, and belief in the idea of equality.

First, both communism and liberal democracy reject the teleological conception of human nature. Neither takes seriously the classical idea that human beings have a discernible “telos” or purpose. This is one marker of their joint origin in modernity. As the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre points out in After Virtue, the teleological view of man as having “an essence which defines his true end” has been largely rejected by modern thinkers, while the very notion of man’s having any essence at all has come to be regarded as dubious.11. Marxists, particularly those in academia and the West, may protest that communism at least is based on a more robust anthropology. Legutko is well aware that Marxist literature contains the humanistic promise of “bringing human potential to its full flourishing.” But he notes that having begun with such a lofty message, communists in practice quickly lowered their aspirations. In real, historical communism—the one he is interested in—a model communist came to be defined, he writes, by three, much more minimalist, elements: “ideology, work and leisure.” Legutko argues that this anthropological conception of human nature is tied to the Enlightenment repudiation of the “excessive demands” imposed by aristocratic and religious ideals in the Middle Ages and antiquity. Because the ends or objectives of individuals can no longer be judged with reference to a human nature or essence, there can be no justification for limiting our pursuit of pleasure, utility and comfort. Liberal democracy and communism thus “legitimize the lowering of human aspirations”; indeed, as Legutko notes, the word “common” ceases to be a word of disapproval.

The second similarity between liberal democracy and communism is that both see history as a slow progress towards the current order. In modernity, Legutko writes, the past is no longer an object of reverence, but rather something that should be treated with “sympathy mixed with condescension.” The prejudice against the old is encapsulated in typical expressions of condemnation such as when we call things “medieval,” “backward” or “anachronistic,” as well as in the use of “modern” as a term of praise.

The communist claim to uncover historical laws necessitating the overthrow of capitalism is well known. Liberal democracy has nothing equivalent to an official, grand theory of history. But, Legutko notes, it has an implicit narrative to make sense of the past. The past is the history of struggle for freedom and against oppressors—“the struggle between Liberty and Authority” as John Stuart Mill writes—with liberal democracy as “the final realization of the eternal desires of mankind, particularly those of freedom and the rule of the people.” The enemy takes on different forms—monarchy, aristocracy, the church, and later fascism, communism, imperialism, nationalism, and so on—but each is an instance of the basic impulse of anti-liberal and anti-democratic tyranny.

This progressive view of history explains how a theorist like Fukuyama could believe that the triumph of liberal democracy would signal the “end” of historical or political development. It also explains why, as Legutko puts it, opposition to liberal democracy is so frequently seen to signify not just political disagreement but a dangerous attempt to preserve “the remnants of old authoritarianisms.” According to liberal orthodoxy, such an attempt is irrational, like “a desire for a grown man to return to his mother’s womb”—one that should be speedily relegated to “the dustbin of history”22. An idiom, incidentally, borrowed by Trotsky and Reagan alike. and replaced with 21st-century standards.

The third similarity is that both liberal democracy and communism aim to fashion humans and communities according to the demands of equality. According to Legutko, equality defines the West’s modern identity and its image of the future; it is given “a status of the highest value and made a regulating principle.” Humans are seen as primevally equal, and the job of society is to make them equal again. The liberal democratic commitment to equality first manifests itself in equality before the law. But as democratization of society increases and the idea of universal equality takes root, the focus shifts—first onto the persistence of inequality in “people’s customs and habits” and then onto the way people think about and conceptualize the world. Since traditional communities, social relationships, customs and practices tend to be characterized by inequality and hierarchy, they need to be uprooted and remade; and since language shapes people’s thoughts, a “Newspeak” emerges with concepts “so value-loaded that they permit no discussion.”

The final consequence of these egalitarian efforts, Legutko argues, is that all aspects of society are politicized. The constant urging to “change and reform”—on university campuses, in the media, now even by big businesses—and the inevitable failure of the political process to turn our ever greater hopes into reality, is taken to signal the need for ever greater political exertions. The successive battles for freedom end up destroying national and religious particularities developed over centuries, replacing them with new categories—“feminist,” “environmentalist,” “queer”—which lack any organic history or set of shared practices. The outcome is not the flourishing of many different cultures, but rather the profusion of political “identities,” which all share allegiance to the homogeneous liberal democratic culture and politics that made them possible.

Legutko thinks there are many things to learn, and to learn to condemn, from this comparison of liberal democracy and communism, these two “greatest hopes of mankind.” But two in particular should be emphasized. First, Legutko finds the hostility of liberal democracy to Christianity particularly troublesome. The final chapter of The Demon in Democracy is devoted to explaining how today’s liberal democracies tolerate Christianity only insofar as it modernizes and thus becomes subservient to the dominant ideas and institutions—a demand to which some Christians have succumbed. In such a case, Christianity is deprived of any meaningful role in society and, eventually, ceases to function as “a viable alternative to the tediousness of liberal-democratic anthropology.”

Second, Legutko sees liberal democracy as a force driving the decline of the West and its people. Anthropological minimalism and the passion for equality have reduced standards and aspirations, and though it remains capable of economic and technological success, Legutko believes the West’s rejection of its own tradition is connected to its ongoing cultural and economic deterioration. Christian and classical culture, once revered as essential for elevating humanity, are now treated by many in the West as retrograde elements of a premodern, nondemocratic, and nonliberal past. Meanwhile, what is truly valuable in the West has been reinterpreted to lie in liberal democracy, the achievement that redeems the madness that came before.

●

Does Legutko offer a different way forward? It is important to note that The Demon in Democracy offers little comfort to Anglophone conservatives who remain committed to a more genuine—more democratic and free—liberal democracy. Despite attempts to claim Legutko as one of their own, most notably in the foreword to The Demon in Democracy, by the National Review’s John O’Sullivan, Legutko is not opposed simply to the bureaucratic, political or media elites who supposedly hinder the flourishing of a “majoritarian democracy resting on constitutional liberal guarantees.” Nor is he a “populist,” whatever exactly that term really means. A quick glance at the original title of his book—“Triumf czlowieka pospolitego” or “Triumph of the Common Man”—is instructive: for Legutko, the triumph of what is common is the problem, not the solution. Handing power over to the “real people … ordinary people … decent people” lauded by Nigel Farage will hardly suffice.

If The Demon in Democracy offers no road map for politics, in subsequent interviews Legutko has been more explicit about how his ideas might inform contemporary political conservatism. Conservatives, he suggests, should embrace the West as the realm of Christian and classical civilization, a notion rejected not only by today’s left but also by those on the right who are all too eager to claim that they, too, are “open, pluralistic, tolerant and inclusive.” Though the “Christian and Classical roots of this culture, classical metaphysics and anthropology, beauty and virtue, a sense of decorum, liberal education, [and] family” are all under pressure, they have not yet been lost, and Legutko does not think it is too late to recognize their importance for the cultivation of the Western mind. Until conservatives realize that these—rather than, say, tax cuts, economic growth and opposition to media bias—are the things they stand for, they can expect little to change.

What might this recognition entail in terms of pragmatic political action? For Legutko, particularities of time, place and national character are important; there is no reason to believe the same arrangements should rule everywhere. Nevertheless, his own career in politics offers some indication of the practical steps he has in mind. Legutko has served in the Polish Senate, as the education minister, and as the Secretary of State in the Chancellery of President Lech Kaczyński—and in 2009 he was elected to the European Parliament where he is currently the co-chairman of the Euroskeptic European Conservatives and Reformists political group (home also to the British Conservative Party). Central to both Law and Justice and Legutko is the battle against the political project of the contemporary E.U.—the “ever closer union”—on behalf of an alternative, conservative, politics.

Law and Justice has close ties to the Catholic church, and its platform is socially conservative and solidarist. The party, established in 2001 after a split in the political arm of Solidarity—the Catholic-associated trade union behind the anti-communist resistance of the Eighties—emphasizes law and order, patriotism and the de-communization of the Polish state and society; supports intervention in the economy to promote social goals; and opposes E.U. integration insofar as it is political rather than economic. Having led the government from 2005 to 2007, the party returned to power after winning elections in 2015. Over time it has consolidated Poland’s political right by taking over support from various nationalist and Christian democratic groups: its base tends to be rural, working class, poor and old.

Overall, the politics of Law and Justice has proved to be popular domestically, despite spirited opposition from more liberal Poles. As Remi Adekoya writes in Foreign Affairs, the party “has responded to two of the major issues of contemporary European politics—identity and inequality—by effectively combining social conservatism and nationalism with welfarism.” Expectedly, it has met with much disfavor in Western Europe, and Legutko’s tenure in the European Parliament has seen a souring of Poland’s relationship with the E.U. In the past two years, Brussels has accused Poland of violating the rule of law and democracy, with the European Commission threatening sanctions and the removal of E.U. voting rights. The conflict has primarily centered on a series of proposed reforms to Poland’s judicial system. (Among them, in the name of restoring checks and balances, Poland wants to give its legislature a partial say in the appointment of judges. The E.U. has claimed the changes undermine judicial impartiality.) But Poland’s refusal to accept E.U. refugee quotas (even as it has welcomed Ukrainians displaced by the war in Donbass), and its conservative stance on moral and cultural issues, such as abortion, have also been sticking points.

In response to E.U. demands, the Polish government has asserted the right of member states to decide on such internal issues in accordance with their national traditions. Poland is a heavily Catholic and, since World War II, culturally and ethnically homogeneous country. Pew Research polling from 2016 shows that over 70 percent of Poles think being Catholic is important for being Polish, and 95 percent think the same about sharing national customs and traditions. (According to other surveys, three quarters of Poles oppose accepting any asylum-seekers from the Middle East or Africa, and, remarkably, even though nine in ten support E.U. membership, over half would refuse Muslim migrants even at the cost of leaving the E.U.)

Many Polish politicians thus find themselves on a collision course with Brussels as it aims to create a Federal Europe. The conflict between the E.U.—which Legutko describes as displaying “the order and the spirit of liberal democracy in its most degenerate version”—and Poland shows why, for Legutko, any conservative awakening must begin with individual nation-states.

Reflecting on Poland before the fall of communism, Legutko writes that, despite common narratives today, the strongest impetus for resistance had “little to with liberal democracy.” Rather, it lay in “patriotism, a reawakened eternal desire for truth and justice, loyalty to the imponderables of the national tradition, and—a factor of paramount importance—religion.” The heroes of yesteryear stood for the very things modern liberal democracy is hostile towards—the nation, tradition and religion. Recovering these as part of a new way of thinking and speaking about society, politics, the common good and the future is key for Legutko if we are to rise up from our present mediocrity.

●

Still, a question persists: What is the best political arrangement to overcome the commonness Legutko laments? Legutko’s emphasis on moving beyond liberal democracy and its stated emphasis on pluralism, equality and individual freedom will no doubt provoke some skepticism: Is Legutko’s conservative criticism anything more than a call to return to authoritarianism, religious intolerance and other forms of bigotry? Perhaps the most difficult challenge of The Demon in Democracy is its insistence on standards beyond freedom and democracy, on the possibility of elevating man and revitalizing the West while at the same time preserving our basic liberties.

As is typical of resolute critics, Legutko is much clearer on the nature of the problems than on where he hopes for us to end up. But The Demon in Democracy does resuscitate a classical notion that our times have forgotten: the mixed regime. Legutko notes that most governments are defective because they are one-sided, overemphasizing the monarchic, the oligarchic or the democratic element. The solution is to mix the three types and craft the regime accordingly, ensuring “democratic representativeness but at the same time some oligarchic-aristocratic institutions … [to] preserve a form of elitism as well as some form of monarchy guaranteeing the efficiency of governance.” This idea, Legutko notes, is at the core of the republican tradition and can be seen in the philosophy behind the U.S. Constitution, which, reflecting the Founders’ aversion to mob rule, contains many limitations on democracy.

What exactly a mixed regime would look like today, when “democratic” is almost universally considered a term of praise, is an open question. But Legutko implies that some such arrangement would help prevent the descent into democratic commonness by tempering the tendencies of democracy and liberalism. As a regime it would be more internally diverse and less restrictive than the current order, incorporating some undemocratic institutions and making room for nondemocratic sensibilities. It would thus be more likely to leave space for communities to flourish, tradition to persist, and religion to emerge from the margins—all helping to sustain the sense that humanity can sometimes transcend the vulgar and the common.

Though he extols certain virtues and has a clear conception of the good, Legutko does not claim to have all the answers—and he maintains openness about the future. His description of his experience in Poland is again telling in this regard. The liberation of Eastern Europe held the great promise of an open future, he believed: with the fall of the Berlin Wall, it seemed the newly independent countries would each have a chance to develop a political system and society best suited to their heritage, their national particularities and the pursuit of the good. Instead, the promise quickly evaporated as nations leaped into Western liberal democracy, initiating a new era of conformism. Beneath the vigorous ire of Legutko’s writing one can sense a faint nostalgia of what could have been but was not—and a faint hope for what might be.

And yet The Demon in Democracy is not an optimistic book. Though it is hard to know the outlook for Eastern Europe or the West, Legutko parts on an apprehensive note. It seems likely, he writes, that “human history will add some new chapters” after “the current view of man spends itself and is considered inadequate.” But he acknowledges another possibility. Perhaps modernity has “divulged … a basic truth about modern man,” with further fundamental changes in human history unlikely; “except changes for the worse.” If so, “it will be a final confirmation that [man’s] mediocrity is inveterate.” The question, then, is how it could ever have been otherwise.

Art credit: Benjamin Sack

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.