When the train stalled on the bridge, his face lost the subtle yellowish pink it’d held in Brooklyn. His eyes scoured the car—window, commuter, window, commuter—in search of compassion or an exit. He reached for a railing and gripped it until the blood disappeared from his knuckles. When it seemed that he might scream or do something else similarly drastic, he lowered himself slowly into a crouch and feigned the tying of shoes.1

“Ladies and gentlemen, there is train traffic up ahead. We will be moving shortly,” said the omniscient voice, after we’d been stopped for more than a minute.

I peered over again at the anxious man. He was long and dark blond, symmetrical and fit, like a department-store catalog model. His eyes, however, were squeezed shut with the intensity of imminent pain.

After a couple of minutes, the train conductor repeated the announcement exactly as he had said it before, prompting a collective exhale from the crowded car, except for the catalog model, whose wide shoulders remained rigid and pressed tightly against the car doors. Turning away from him now felt as if I were, in some way, contributing to his suffering. After all, I understood panic. I’d worked downtown on 9/11. I still recalled the year of avoiding crowded spaces—no rush hour, no Midtown, no Bleecker—or any situation that might signal to my brain that I had no control over my immediate surroundings. I recalled, too, the social worker who talked me down from the worst of it. “The brain, like any other part of the body, needs time to heal, but longer,” she said. For months, she taught me breathing and visualization exercises: things that could have helped the catalog model.

In these should-I-or-shouldn’t-I moments, I think of my father, who, instead of merely observing a perfect stranger in distress, might inquire about their well-being or strike up a conversation to distract them. It would never occur to my father to curtail his humanity in order to navigate social norms or insecurities. In fact, my father doesn’t have insecurities. He has the confidence of a middle-class white man despite not being middle-class or white. This is something he acquired in his youth, in a country where he had been part of the mainstream, as well as financially untroubled—first and last time. For my mother, it was different. Her formative years, in a more beleaguered country, were defined by inequity and political repression. “Better to mind your business,” she’s said many times, in all types of situations. Coming to the aid of a catalog model on a train would be far afield of her comfort zone; instead, she’d find a spot on the ground or stare at her cuticles.

I got up from my seat and squeezed, with apologies, through the tangle of exasperated travelers. When I was standing before the catalog model, I whispered, “Hold your breath.”

“What?”

“Try holding your breath.”

He closed his eyes again.

“Panic, right?” I asked.

He nodded slow and repeatedly, with the cadence of a lethargic woodpecker.

“Breathe in slow. For five seconds,” I explained. “Then hold it for five seconds. And then exhale slow, another five seconds. Like this.” My chest filled, and I unfurled my fingers, one at a time. He did his best to mimic my breathing but kept his hands tightly fisted at his sides. Beside us, an elderly woman with magenta-caked lips and a billowy, smoke-colored wig briefly peered up before returning to her crossword puzzle.

“Keep doing it. Eventually you’ll feel some relief,” I said.

The catalog model paused from counting. “How did you know?” he asked.

Before I could respond, a tremendous jolt tipped my body into his, momentarily. The train had resumed. The relief enlarged his eyes and released his jaw, shoulders, chest and hands, all at once. His green eyes lingered on me long enough to add another layer to our relationship.

Green eyes. Eric had them too. Sometimes they were blue; sometimes mosaic-like but predominantly yellow, like cartoon bees.

In retrospect, it was clear that Eric and I weren’t going to last. We shared a couple of languages, a love of Star Wars and the ambiguous political territory between queer and gay, but it wasn’t enough. Our relationship often felt like a vacation fling, characterized primarily by insurmountable geopolitical factors. To begin with, his family disliked me. They associated my skin color with domestic work and maybe savagery, which only ever made me want to be a savage around them, but also a good cook. His friends, too, were hills to climb. Always looking askance. Never completely at ease. Quick to note that I was emotional, passionate or upset during political discussions—to be fair, there is little in politics that I don’t take personally. My parents weren’t particularly helpful either. They tried too hard. They revered Eric in a way that only underscored our differences. My friends thought he was cute and sweet, but initially, the ones who’d known me longest and strangest withheld something, almost as if they knew. Our differences weren’t the roots of our problems, but they were the fertile soil and the wind that scattered the seeds. Years of navigating good intentions and misunderstandings, family gatherings and holiday parties, supermarkets and sub-dom play proved plenty for us both. At some point, I found myself snarling involuntarily. He still calls me, and I still answer, but—it’s over.

●

“Feeling better?” I asked the handsome poplar tree swaying before me.

We’d entered the underground. The sun was no longer, and we were all at the mercy of the harsh fluorescence.

“A bit better,” he responded after a forceful exhalation.

At Canal Street, we filed out with the others and remained silent on the grimy platform as thousands of people disappeared in an instant.

“Thank you for this,” he said.

“Takes one to know one.”

“Huh?”

“I’ve been where you are.” I smiled. “I’m terrible on planes.”

“I’m trying to wean myself off my anxiety meds. I just haven’t gotten a handle on the dosage yet,” he explained casually. He eyed me with a similar shamelessness. I was dressed as I usually am, like a well-meaning college professor with aspirations.

Just then, our ties blew up from our chests; a harbinger gust of wind signaled an approaching train. “I think I’m going to walk a bit,” he said, when the platform began to rattle. “Maybe to the next station, until I feel better.”

Gray and black coats dominated the conveyor belt of sidewalk traffic, most of which migrated further downtown, toward city hall and the campus of courthouses. We stood out of the way, beneath an awning where fruit vendors were preparing their displays. Two towers of worn wooden crates teetered beside us. Dull-pink lychees and verdant papayas peeked through the slats, catching an uneven light from an otherwise unobstructed late-winter sun.

“Thank you. That was very kind,” he said.

I smiled again, more with my eyes than my mouth.

“Where are you from?” he asked, as we joined the procession north along Broadway.

My least favorite question.

“What do you mean?” I prodded, instead of recounting my family’s early-eighties exodus from the city to the suburbs.

“It’s just that, you know, New Yorkers aren’t very friendly.”

“Oh. We’re just frustrated by all the New Yorkers who still behave as if they just got here.”

He laughed authentically, it seemed. A man who can take a joke at his own expense, I thought.

We continued, comfortably silent, through the crossfire of commuters, as if we’d known one another for years. At the second or third corner we stopped as everyone else jaywalked ahead. “Where are you going?” he asked.

My hope had been to spend the morning reading my students’ papers—an analysis of the economic risk factors for diabetes—before teaching in the afternoon.

“I have nothing pressing till later—in case the gentleman is wondering,” he said with a sportive British accent that should have been silly, but was altogether disarming.

This was the sort of situation I’d been trying to avoid since Eric. It wasn’t that I was about to succumb to sex with a perfect stranger that concerned me; the honesty of desire is one of my favorite parts of being gay. It was the vicious cycle of imprudence. Why, with all the men this city had to offer, did I find myself on a precipice with this one? Had I learned nothing in the last six years? Was this the inevitable outcome of having spent my formative years in a mostly white school district? Or was this merely an adolescent He-Man fantasy that I would never outrun? Fuck. Had I overlooked all of the anxious men of color on the subway? How deeply was white supremacy burrowed inside of me?

“I have a place around here—my friend’s place actually,” I said.

“Nearby, eh? That’s convenient,” he responded, with his words and his eyebrows.

●

Gerardo’s apartment.

Gerardo and I had been acquaintances, vaguely, in high school. We were two of the few Latinx kids in a mostly Irish-Italian town. I didn’t know then that he was gay—he didn’t know about me either—but the summer after graduation, I ran into him in the mirrored bathroom of a multi-level club in Chelsea that no longer exists. We were both high on different things and ended up in a stall together with our pants around our ankles. Months later, we sat a few pews apart from one another at our sisters’ communion mass. From then on, we became like long-lost friends, rekindling something that we’d never had to begin with.

Gerardo went to college in the city. Whenever I’d visit, he’d let me bring guys back to his place, a fifth-floor one-bedroom on Avenue D. He’d relinquish his apartment and go out to meet friends or grab ice cream and leave me a key under the welcome mat. When he was ready to come home, he’d call me from the pay phone on the corner and let it ring twice. That was my cue. If Gerardo also happened to have a date, I was relegated to his living room couch. One time, both of us, along with our dates, found ourselves in his bedroom, but that was more about the experience than the participants. Gerardo was now a well-known chef who occasionally judged reality-TV cooking competitions. He’d spent most of the last ten years on the West Coast but had moved back to New York recently.

“Mijo, it’s not even 9am!!!” Gerardo texted back.

“Details forthcoming.”

“This is unacceptable,” he wrote, adding a slew of little emoji figurines.

Before I could reply, he sent, “Give me ten, so I can brush my teeth and get out of here.”

“I owe you,” I texted.

“This break-up has you twisted.”

“Key under the mat?”

“I’ll leave above door frame. Don’t use up all my lube!”

●

The stairs were steep, splintered and painted an institutional maroon that was once widespread. The banister was loose but not unsafe. The four-floor co-op was a mix of long-term renters and recent owners. By the time we reached the third floor, both of us were mildly winded.

“You sure about this?” I asked.

“I think it was my idea.”

“Yeah, but you’ve had a rough morning, and I, uh—”

“Don’t want to take advantage of me?”

I shrugged.

Years ago, not long before I met Eric, a girlfriend of mine introduced me to her friend, an assistant principal of a charter school in Manhattan. It happened in Williamsburg, at a dark bar with neon-pink lighting. He was thin, my height, big-eyed and had a shaved head. We hit it off and spent the night drunkenly making out in a corner booth. During the pauses, we made small talk.

“Where are you from?” was his first question.

“Queens, originally.”

“No, I mean your people.”

“My father’s from Colombia. My mother is from El Salvador,” I responded.

“I love poposas!” he screamed.

Instead of correcting him, I told him I could someday take him to a great pupusa spot in Woodside. Someday, as if our 25 minutes of tongue action presupposed a future.

“I’d fucking love that!” he shouted, over the music and directly into my ear.

After a bit more making out, his hand traveled up my leg and unzipped my pants. As he struggled with the button, I pulled his hand away. “We can go back to mine,” I said.

I didn’t live far, but the assistant principal was opposed to leaving the neighborhood because he had to get up early the following morning. His place was only a few blocks from the bar, but it was out of the question: “My roommate’s parents are in town,” he explained.

We continued kissing for a bit longer, until he interrupted to ask if I was into hitting.

“Hitting?”

“Rough play,” he explained.

I wasn’t sure exactly what he meant. “Maybe,” I said.

Before I knew what hit me, he’d hit me. The open-hand whack landed primarily on my face but also caught my ear. Along with the ringing came a rush of cortisol, epinephrine and childhood memories.

“Like that?” he asked, as the tip of his tongue licked the corners of his mouth.

I was stunned and grateful for the darkness of the space, which obscured the involuntary tears in my eyes. Whatever traumas I was regurgitating in that moment, however, didn’t keep the assistant principal from straddling me and kissing my neck. “I want you to fuck me,” he said.

We didn’t fuck, but we continued making out before exchanging numbers. A week later, I was horny, lonely and misguided. “Plans tonight?” I texted.

“Hey. Wish I could. Long work week. Exhausted.”

“I have a massive hard-on and all the ingredients for a martini,” I responded.

“Tempting, but not tonight.”

“You sure?” I messaged, after each martini. There were three martinis.

He didn’t respond to those messages, but the following morning, my friend called to say that the assistant principal was really put off by how aggressive I’d been.

I was mortified. I sent an apology text, which he accepted graciously.

When I later recounted the story to Gerardo, he was incredulous: “Are you fucking kidding me with this queen? Get outta here! What you should do is smack him with a stack of pupusas.”

“Seriously, this is exactly why I don’t mess with white boys,” Gerardo continued. “Tops or bottoms, young or old, assistant principal or janitor—it doesn’t matter—they want control. Gay white men are like the Israel of the LGBTQ world: they don’t know if they’re the predator or the victim in their own role-plays.”

“Mijo, what you need to do is quit going to gay bars and come with me to the next family dinner.”

Gerardo had, several times, invited me to one of his after-work work events—loose gatherings of colleagues from all over the city, most of whom were BIPOC, and specifically Latinx. The problem was that all the men I ever met through Gerardo could only hang out after midnight and on Mondays.

●

I looked directly into the catalog model’s eyes: “Are you sure?”

“Don’t worry. I’m a big boy,” he responded, with no indication of the frailty that had gripped him over the East River.

After nearly twenty minutes of foreplay on a leather couch that squeaked softly whenever we repositioned ourselves, he whispered, “Can I fuck you?”

A red flag went up. Did he want to fuck me or dominate me? Both sounded nice, so long as I wasn’t unwittingly participating in a Manifest Destiny-themed fantasy. “We can give it a try,” I said. “No promises.”

“Thanks,” he replied.

What an odd thing to say. Odd and, in a way, sweet. It reminded me of the deference and politeness in the early years with Eric.

“When was your last STI screening?” I asked.

“Tested last month. Negative across the board. You?”

“I got my results last week. All clear. But condoms anyway.”

“Of course.”

“Maybe next time,” I said, by way of a canned response that wasn’t meant to be sincere.

“There’s a next time?”

“Shhh.” I pressed my index finger against his lips.

It took a few tries for him to get inside of me. He had a fine, average-size cock, but I hadn’t bottomed in recent memory. For years, anal sex had been a special occasion, and in the coda of our relationship, Eric and I rarely celebrated anything.

Sex with the catalog model proved to be of the type that rarely happens. All of it—pace, passion, synchronization, duration—seamless, thrilling and precise. Afterward, we lay silent but awake in the sunlit room, breathing softly, shadows tucked within the rumpled bedsheets, my right leg entwined in his left. His torso was mounded and hard like fruit on the verge of ripeness; his abdomen taut but not intimidating. We were only a year apart in age, but he had the lines, freckles and moles of someone older: the burden of descending from those early humans who wandered away from the equator.

He asked questions—where I worked, where I grew up, where I’d gone to school—that felt more intimate than what had just occurred between us. I responded succinctly to everything.

“And you, what do you do?”

“I’m a lawyer. For the city,” he said. “Homeless services.”

“Well, that’s nothing to be ashamed of.”

“Most days it isn’t. Why? Are you ashamed of what you do?”

“Sometimes.”

He laughed easily and ran his fingertips across my knee, but then wanted to know if I was serious.

“When I was in college, my classes were taught by tenured professors who wrote books. People who exuded authority. People with proper offices full of shelves and plaques. People who made time to meet with their students. In my department, eight of the ten faculty members are adjuncts who earn almost nothing and have little job security. They run around the city teaching at multiple colleges, which is bad for us, bad for the students, bad for the school. In effect, I teach in a public-health program where health is of secondary importance.”

It was possible that I was being too preachy, but I felt free of the responsibility to make a good impression.

“You sound like someone who’s unhappy in his work environment,” he said after a silent bit of head nodding.

“Good lover and astute. Rare combo.”

“I’m a good lover? Cool,” he said, like an insouciant teenager, the kind that would have made me swoon in my youth. Then he turned over, almost onto me, and traced my nipples with the tip of his nose and his lips, pausing occasionally to kiss me.

“I should get going. I have a stack of student papers on my desk.”

He set his elbow onto the bed and cradled his chin in his hand. “Oh.”

“You should probably get dressed too. I can’t really let you stay here.”

“Of course.”

The catalog-model-cum-lawyer leapt to his feet with the alacrity of an athlete. I found myself feeling self-conscious and awestruck by his nudity, by a beautiful body in full relief. His thighs and calves were magnificently thick and well-defined, like slabs of stone that had been carved into being. The muscles in his back bulged subtly as he bent over to pick up his underwear and pants, and as he pulled thin, pin-striped socks over his feet. I felt, for a moment, as if I were watching my high school girlfriend’s shirtless father watering the lawn.

I turned toward a window. Gerardo’s plump succulents adorned a red-oak shelf installed at the frame’s midpoint. Gerardo isn’t only a magician in the kitchen, he’s an extraordinary keeper of plants. It’s a form of meditation that’s aided his sobriety for almost ten years.

“Should I strip the bed?” he asked.

“Nah, leave it. My friend won’t care.”

Fully dressed, he reached halfway across the bed (one foot on the ground, one knee on the mattress) for a tissue I’d left on my side. In fact, he collected all the tissues and condoms and took them to the bathroom. He was someone with manners and without germ hang-ups. When he reappeared, his mouth was a gentle grin, not an action so much as a semi-permanent state. He asked for my phone number.

“Just a one-off then?” he said, when I hesitated.

“Listen, I recently ended something.”

“You ended it?”

“Mutual, but I’m—”

“How long ago did you break up?”

“Two months—”

“Oh—”

“But we’d been together for six years.”

“I see,” he said authentically, no longer playful. “Maybe just a drink then?”

Reluctant to explain my newfound and complicated stance on love—namely, that its chances for success improve if it’s segregated by race, class, culture, political ideas, dietary restrictions—I gave him my number.

“I promise not to dial or text drunk,” he said. “I’ll call you now, so that you have my number.”

My phone rattled in my pocket.

I led him down a long, brick corridor and through the modern, angular living room, also with an exposed-everything motif—brick, beams, pipes. Gerardo had been dating an architect when he bought the apartment. At the front door, the lawyer for homeless people (or maybe he was the one who defended the city against homeless people) took my hand. He stepped toward me, placed his free hand on my back, and pressed me into him. He dipped his head slightly to account for our height disparity—three or four inches. His lips were warm and subtly swollen from their earlier efforts. Our mouths opened slightly, and I tasted a mélange of myself—saliva, armpits, cock, asshole, feet. We were no longer saying goodbye.

“You’re trouble,” I said, as I stepped back.

“Hopefully more fun than trouble.”

This was a gentle, endearing sort of audaciousness; something special, I thought. I slid my hands into my pockets, attempting to conceal my growing erection. He noticed. “My first meeting isn’t until one,” he said. “We can hang out a bit longer if you—”

“I can’t.”

“Okay. Another time, I hope.”

After he left, I stripped the bed, showered quickly, and ate something in Gerardo’s fridge that looked like chicken, but tasted like duck.

I didn’t want to go back underground. Instead, I wrapped my scarf tightly around my neck and chin and assumed a brisk pace uptown.

That night, Gerardo sent a few recriminatory texts:

“I don’t mind you ate my rabbit, but you could have put the sheets in the wash.”

“And you owe me lube!”

“White guys make you inconsiderate.”

●

Five days later, the lawyer sent three messages in under an hour. It was Sunday morning, shortly after ten. A few blocks away, the bells of the French-speaking Baptist church, filled with well-heeled Haitians, had only just ceased clanging. I was copying my antiquated music collection, one CD at a time, over to an external hard drive—something Eric had for years encouraged me to do. This tedious form of transcription had become my evening and weekend drudgery since the breakup. There would be no room for these relics in the new place, a single-salary one-bedroom not too far from the neighborhood I’d called home for the past decade—a part of Brooklyn I’d been complicit in gentrifying, which I could no longer afford.

I’d just ripped Funky Divas by En Vogue—Actually by Pet Shop Boys was next—when I heard the first text: “I’m free for the next few years, if you want to take a walk or eat something.”

Five CDs later, I still hadn’t replied. My phone again dinged: “Actually, I have a friend’s wedding in Seattle in December, but since it’s only March, we can plan ahead.”

This was the sort of charming thing that Meg Ryan or Julia Roberts encountered regularly. I slid the phone across the slick, recently renovated wood floors. In retrospect, Eric and I had fixed up our place in order to disguise our underlying issues—the urban renewal of our relationship.

3 Years, 5 Months and 2 Days in the Life of… by Arrested Development had just finished copying when the lawyer’s final text came through: “No pressure, but if you change your mind, I’ll be happy to hear from you.”

His allure and his scent lingered, like a smolder in the wee hours. A few times over the next week, I found myself reading the text messages and concocting clever responses. I found, too, that the loneliness of bedtime and dinner preparation was almost enough to overturn my convictions.

I resisted. The chances were high that this man had white parents and white friends and that I’d be explaining where I was from for the next ten years. Maybe, too, he was the kind of white person who equated race with class. Or, worse, the kind who couldn’t see the obvious link between the two. Over time, we’d learn to avoid certain topics. If I were lucky, he’d nod along and keep trying. If I were unlucky, he’d accuse me of overreacting and, secretly, I’d question his character. Eventually, an internal hierarchy mirroring the external one would settle upon us, and I’d wonder why he was getting attention or respect that I wasn’t and whether I was using his status as a shield to the world. I’d spend the remainder of my life disentangling intention from impact, lamenting that I had gone to a private university upstate instead of a city college.

Or maybe I was mistaken, blinded by cynicism. Integrated love didn’t have to bear the weight of such a grim outlook. He’d try, and I’d try, and together we might create something immersive, nurturing and revolutionary. Our love would envelop us, like a force field or a good angel with broad, unfurled cages for wings. And I’d never again have trouble hailing a cab.

●

Whenever I was tempted to call the lawyer, I contacted Gerardo instead. Each time, he responded the same thing: “#selfcare.” This was his mantra. After a half dozen times of reaching out, Gerardo told me to get a boyfriend: “This is what online dating is for. Do the work.” A few minutes later, he texted again, “Come by restaurant tomorrow. New vegan menudo on menu. Seitan = panza. I’ll intro to bartender. Gorgeous, single, Guatemalan, they/them. Late 20s. Puppy-dog type. Needs someone grown-up like you.”

I wasn’t particularly interested in taking care of anyone or in being the responsible half of anything or in having a get-to-know-you drink with someone in the middle of their work shift, but I was already half-asleep when Gerardo’s message came through. “Okay. I’ll meet them,” I texted back. I was choosing to be optimistic, instead of dwelling on the potential class implications. “I’ll swing by after the gym.”

The following morning, I awoke hopeful—I put on my good socks and a pair of snug underwear—but by the time I reached the train station, I felt a bygone disarray in my bloodstream. A swoosh of electricity traced my body, head to toe, inside and out. I recognized the sensation. I’d been accustomed to feeling it in airports, in the moments before I committed to the high-altitude terror: the necessary forgoing of my sanity, in order to escape, explore or experience life. Or maybe it was the reverse: not the anxiety of seizing life, but the disappointment of it passing me by. I thought of the trips I hadn’t allowed myself to plan. I thought, too, of the time I’d panicked at LAX and missed my connecting flight to Japan. It was an inconvenient and expensive change to my itinerary, but it resulted in a fun stay in Los Angeles, where I was able to regroup and shore up my courage to fly to Tokyo two days later.

As I held my place on the crowded subway platform, I closed my eyes and concocted a serene setting—a steady rivulet at my feet, snowcapped mountains in the distance—but it wasn’t enough to overpower the striking unease. I tried next to imagine my fears as a two-dimensional rendering that I could fold up to the size of a business card and stuff into my breast pocket. When this, too, failed to calm me, I dug into my bag for headphones, selected Dreaming of You, Selena’s first posthumous release, and skipped straight to the album’s second half.

The train rolled into the station, and I considered for a moment remaining on the platform, but when the doors opened, I rushed in alongside everyone else. I nabbed an empty seat by a window and crossed my legs, casually cradling one knee against my chest. The doors closed, and we entered the tunnel. I filled my lungs and disengaged my shoulders. The anxious moment passed.

The train snaked slowly; then, at a faster pace. As we rounded a bend, I glimpsed into the car behind mine. There he was, the catalog model, sandwiched between two much shorter people: the illusion of a giant. He wore standard white headphones, and his hair was parted neatly to one side. His face was as handsome and mirthful as it had been when we’d said goodbye. He looked straight ahead, but I couldn’t see what had caught his stare. Before the train straightened out, I was momentarily in his sights. I turned away too quickly to be anything but obvious. The banner of advertisements above—a vocational college, a storage company, a PSA about smoking and oral cancer—kept my attention until we reached the bridge. Once there, the car filled with a light that altered the panorama, illuminating the morning glares of the undead—seated, standing, gripping, business casual. I eyed a stain on the floor that was immediately darker because of the contrast. It was bigger than a large coin, but not by much. It had once been gum: vibrant, bright-colored, probably pink; now, dull, lifeless and permanent. Certainly an easily explained metamorphosis, it has nonetheless always puzzled me. As the natural light receded from the car, my focus did too. The train was decelerating. I had a few stations yet to go. I kept my gaze low and searched the car for something else to hold my attention.

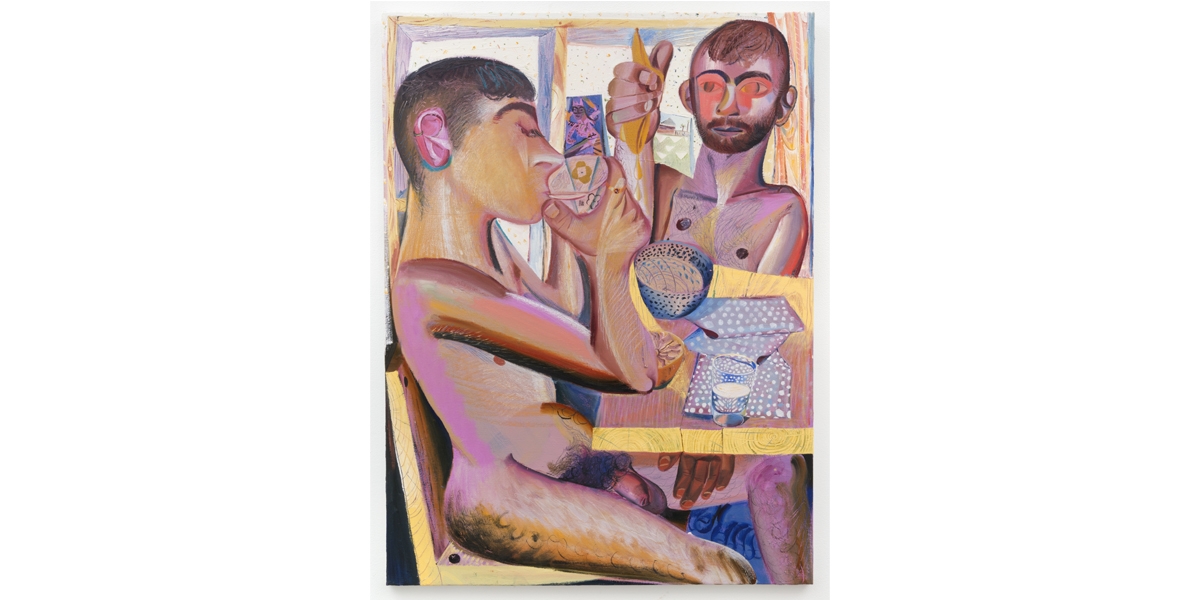

Art credit: Louis Fratino, “Dolphin Street,” Oil and crayon on canvas, 30 × 24 in., 2017 (top image); “Grapefruit Breakfast, 2017. Oil and crayon on canvas, 40 × 30 in. (second image) © Louis Fratino, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

When the train stalled on the bridge, his face lost the subtle yellowish pink it’d held in Brooklyn. His eyes scoured the car—window, commuter, window, commuter—in search of compassion or an exit. He reached for a railing and gripped it until the blood disappeared from his knuckles. When it seemed that he might scream or do something else similarly drastic, he lowered himself slowly into a crouch and feigned the tying of shoes.1The title is a reference to the Jesús Colón essay. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/video/little-things-are-big-jes-s-col-n?utm_term=&utm_campaign=DSA&utm_source=adwords&utm_medium=ppc&hsa_tgt=dsa-19959388920&hsa_grp=75449327748&hsa_src=g&hsa_net=adwords&hsa_mt=b&hsa_ver=3&hsa_ad=333182733493&hsa_acc=4949854077&hsa_kw=&hsa_cam=1635938820&gclid=Cj0KCQjwuL_8BRCXARIsAGiC51AlUMGwl-h7O6ezMR_L2V0KVDj0M1f5cxVVK4Ny9d26U4ctZ2K_rogaAoK5EALw_wcB

“Ladies and gentlemen, there is train traffic up ahead. We will be moving shortly,” said the omniscient voice, after we’d been stopped for more than a minute.

I peered over again at the anxious man. He was long and dark blond, symmetrical and fit, like a department-store catalog model. His eyes, however, were squeezed shut with the intensity of imminent pain.

After a couple of minutes, the train conductor repeated the announcement exactly as he had said it before, prompting a collective exhale from the crowded car, except for the catalog model, whose wide shoulders remained rigid and pressed tightly against the car doors. Turning away from him now felt as if I were, in some way, contributing to his suffering. After all, I understood panic. I’d worked downtown on 9/11. I still recalled the year of avoiding crowded spaces—no rush hour, no Midtown, no Bleecker—or any situation that might signal to my brain that I had no control over my immediate surroundings. I recalled, too, the social worker who talked me down from the worst of it. “The brain, like any other part of the body, needs time to heal, but longer,” she said. For months, she taught me breathing and visualization exercises: things that could have helped the catalog model.

In these should-I-or-shouldn’t-I moments, I think of my father, who, instead of merely observing a perfect stranger in distress, might inquire about their well-being or strike up a conversation to distract them. It would never occur to my father to curtail his humanity in order to navigate social norms or insecurities. In fact, my father doesn’t have insecurities. He has the confidence of a middle-class white man despite not being middle-class or white. This is something he acquired in his youth, in a country where he had been part of the mainstream, as well as financially untroubled—first and last time. For my mother, it was different. Her formative years, in a more beleaguered country, were defined by inequity and political repression. “Better to mind your business,” she’s said many times, in all types of situations. Coming to the aid of a catalog model on a train would be far afield of her comfort zone; instead, she’d find a spot on the ground or stare at her cuticles.

I got up from my seat and squeezed, with apologies, through the tangle of exasperated travelers. When I was standing before the catalog model, I whispered, “Hold your breath.”

“What?”

“Try holding your breath.”

He closed his eyes again.

“Panic, right?” I asked.

He nodded slow and repeatedly, with the cadence of a lethargic woodpecker.

“Breathe in slow. For five seconds,” I explained. “Then hold it for five seconds. And then exhale slow, another five seconds. Like this.” My chest filled, and I unfurled my fingers, one at a time. He did his best to mimic my breathing but kept his hands tightly fisted at his sides. Beside us, an elderly woman with magenta-caked lips and a billowy, smoke-colored wig briefly peered up before returning to her crossword puzzle.

“Keep doing it. Eventually you’ll feel some relief,” I said.

The catalog model paused from counting. “How did you know?” he asked.

Before I could respond, a tremendous jolt tipped my body into his, momentarily. The train had resumed. The relief enlarged his eyes and released his jaw, shoulders, chest and hands, all at once. His green eyes lingered on me long enough to add another layer to our relationship.

Green eyes. Eric had them too. Sometimes they were blue; sometimes mosaic-like but predominantly yellow, like cartoon bees.

In retrospect, it was clear that Eric and I weren’t going to last. We shared a couple of languages, a love of Star Wars and the ambiguous political territory between queer and gay, but it wasn’t enough. Our relationship often felt like a vacation fling, characterized primarily by insurmountable geopolitical factors. To begin with, his family disliked me. They associated my skin color with domestic work and maybe savagery, which only ever made me want to be a savage around them, but also a good cook. His friends, too, were hills to climb. Always looking askance. Never completely at ease. Quick to note that I was emotional, passionate or upset during political discussions—to be fair, there is little in politics that I don’t take personally. My parents weren’t particularly helpful either. They tried too hard. They revered Eric in a way that only underscored our differences. My friends thought he was cute and sweet, but initially, the ones who’d known me longest and strangest withheld something, almost as if they knew. Our differences weren’t the roots of our problems, but they were the fertile soil and the wind that scattered the seeds. Years of navigating good intentions and misunderstandings, family gatherings and holiday parties, supermarkets and sub-dom play proved plenty for us both. At some point, I found myself snarling involuntarily. He still calls me, and I still answer, but—it’s over.

●

“Feeling better?” I asked the handsome poplar tree swaying before me.

We’d entered the underground. The sun was no longer, and we were all at the mercy of the harsh fluorescence.

“A bit better,” he responded after a forceful exhalation.

At Canal Street, we filed out with the others and remained silent on the grimy platform as thousands of people disappeared in an instant.

“Thank you for this,” he said.

“Takes one to know one.”

“Huh?”

“I’ve been where you are.” I smiled. “I’m terrible on planes.”

“I’m trying to wean myself off my anxiety meds. I just haven’t gotten a handle on the dosage yet,” he explained casually. He eyed me with a similar shamelessness. I was dressed as I usually am, like a well-meaning college professor with aspirations.

Just then, our ties blew up from our chests; a harbinger gust of wind signaled an approaching train. “I think I’m going to walk a bit,” he said, when the platform began to rattle. “Maybe to the next station, until I feel better.”

Gray and black coats dominated the conveyor belt of sidewalk traffic, most of which migrated further downtown, toward city hall and the campus of courthouses. We stood out of the way, beneath an awning where fruit vendors were preparing their displays. Two towers of worn wooden crates teetered beside us. Dull-pink lychees and verdant papayas peeked through the slats, catching an uneven light from an otherwise unobstructed late-winter sun.

“Thank you. That was very kind,” he said.

I smiled again, more with my eyes than my mouth.

“Where are you from?” he asked, as we joined the procession north along Broadway.

My least favorite question.

“What do you mean?” I prodded, instead of recounting my family’s early-eighties exodus from the city to the suburbs.

“It’s just that, you know, New Yorkers aren’t very friendly.”

“Oh. We’re just frustrated by all the New Yorkers who still behave as if they just got here.”

He laughed authentically, it seemed. A man who can take a joke at his own expense, I thought.

We continued, comfortably silent, through the crossfire of commuters, as if we’d known one another for years. At the second or third corner we stopped as everyone else jaywalked ahead. “Where are you going?” he asked.

My hope had been to spend the morning reading my students’ papers—an analysis of the economic risk factors for diabetes—before teaching in the afternoon.

“I have nothing pressing till later—in case the gentleman is wondering,” he said with a sportive British accent that should have been silly, but was altogether disarming.

This was the sort of situation I’d been trying to avoid since Eric. It wasn’t that I was about to succumb to sex with a perfect stranger that concerned me; the honesty of desire is one of my favorite parts of being gay. It was the vicious cycle of imprudence. Why, with all the men this city had to offer, did I find myself on a precipice with this one? Had I learned nothing in the last six years? Was this the inevitable outcome of having spent my formative years in a mostly white school district? Or was this merely an adolescent He-Man fantasy that I would never outrun? Fuck. Had I overlooked all of the anxious men of color on the subway? How deeply was white supremacy burrowed inside of me?

“I have a place around here—my friend’s place actually,” I said.

“Nearby, eh? That’s convenient,” he responded, with his words and his eyebrows.

●

Gerardo’s apartment.

Gerardo and I had been acquaintances, vaguely, in high school. We were two of the few Latinx kids in a mostly Irish-Italian town. I didn’t know then that he was gay—he didn’t know about me either—but the summer after graduation, I ran into him in the mirrored bathroom of a multi-level club in Chelsea that no longer exists. We were both high on different things and ended up in a stall together with our pants around our ankles. Months later, we sat a few pews apart from one another at our sisters’ communion mass. From then on, we became like long-lost friends, rekindling something that we’d never had to begin with.

Gerardo went to college in the city. Whenever I’d visit, he’d let me bring guys back to his place, a fifth-floor one-bedroom on Avenue D. He’d relinquish his apartment and go out to meet friends or grab ice cream and leave me a key under the welcome mat. When he was ready to come home, he’d call me from the pay phone on the corner and let it ring twice. That was my cue. If Gerardo also happened to have a date, I was relegated to his living room couch. One time, both of us, along with our dates, found ourselves in his bedroom, but that was more about the experience than the participants. Gerardo was now a well-known chef who occasionally judged reality-TV cooking competitions. He’d spent most of the last ten years on the West Coast but had moved back to New York recently.

“Mijo, it’s not even 9am!!!” Gerardo texted back.

“Details forthcoming.”

“This is unacceptable,” he wrote, adding a slew of little emoji figurines.

Before I could reply, he sent, “Give me ten, so I can brush my teeth and get out of here.”

“I owe you,” I texted.

“This break-up has you twisted.”

“Key under the mat?”

“I’ll leave above door frame. Don’t use up all my lube!”

●

The stairs were steep, splintered and painted an institutional maroon that was once widespread. The banister was loose but not unsafe. The four-floor co-op was a mix of long-term renters and recent owners. By the time we reached the third floor, both of us were mildly winded.

“You sure about this?” I asked.

“I think it was my idea.”

“Yeah, but you’ve had a rough morning, and I, uh—”

“Don’t want to take advantage of me?”

I shrugged.

Years ago, not long before I met Eric, a girlfriend of mine introduced me to her friend, an assistant principal of a charter school in Manhattan. It happened in Williamsburg, at a dark bar with neon-pink lighting. He was thin, my height, big-eyed and had a shaved head. We hit it off and spent the night drunkenly making out in a corner booth. During the pauses, we made small talk.

“Where are you from?” was his first question.

“Queens, originally.”

“No, I mean your people.”

“My father’s from Colombia. My mother is from El Salvador,” I responded.

“I love poposas!” he screamed.

Instead of correcting him, I told him I could someday take him to a great pupusa spot in Woodside. Someday, as if our 25 minutes of tongue action presupposed a future.

“I’d fucking love that!” he shouted, over the music and directly into my ear.

After a bit more making out, his hand traveled up my leg and unzipped my pants. As he struggled with the button, I pulled his hand away. “We can go back to mine,” I said.

I didn’t live far, but the assistant principal was opposed to leaving the neighborhood because he had to get up early the following morning. His place was only a few blocks from the bar, but it was out of the question: “My roommate’s parents are in town,” he explained.

We continued kissing for a bit longer, until he interrupted to ask if I was into hitting.

“Hitting?”

“Rough play,” he explained.

I wasn’t sure exactly what he meant. “Maybe,” I said.

Before I knew what hit me, he’d hit me. The open-hand whack landed primarily on my face but also caught my ear. Along with the ringing came a rush of cortisol, epinephrine and childhood memories.

“Like that?” he asked, as the tip of his tongue licked the corners of his mouth.

I was stunned and grateful for the darkness of the space, which obscured the involuntary tears in my eyes. Whatever traumas I was regurgitating in that moment, however, didn’t keep the assistant principal from straddling me and kissing my neck. “I want you to fuck me,” he said.

We didn’t fuck, but we continued making out before exchanging numbers. A week later, I was horny, lonely and misguided. “Plans tonight?” I texted.

“Hey. Wish I could. Long work week. Exhausted.”

“I have a massive hard-on and all the ingredients for a martini,” I responded.

“Tempting, but not tonight.”

“You sure?” I messaged, after each martini. There were three martinis.

He didn’t respond to those messages, but the following morning, my friend called to say that the assistant principal was really put off by how aggressive I’d been.

I was mortified. I sent an apology text, which he accepted graciously.

When I later recounted the story to Gerardo, he was incredulous: “Are you fucking kidding me with this queen? Get outta here! What you should do is smack him with a stack of pupusas.”

“Seriously, this is exactly why I don’t mess with white boys,” Gerardo continued. “Tops or bottoms, young or old, assistant principal or janitor—it doesn’t matter—they want control. Gay white men are like the Israel of the LGBTQ world: they don’t know if they’re the predator or the victim in their own role-plays.”

“Mijo, what you need to do is quit going to gay bars and come with me to the next family dinner.”

Gerardo had, several times, invited me to one of his after-work work events—loose gatherings of colleagues from all over the city, most of whom were BIPOC, and specifically Latinx. The problem was that all the men I ever met through Gerardo could only hang out after midnight and on Mondays.

●

I looked directly into the catalog model’s eyes: “Are you sure?”

“Don’t worry. I’m a big boy,” he responded, with no indication of the frailty that had gripped him over the East River.

After nearly twenty minutes of foreplay on a leather couch that squeaked softly whenever we repositioned ourselves, he whispered, “Can I fuck you?”

A red flag went up. Did he want to fuck me or dominate me? Both sounded nice, so long as I wasn’t unwittingly participating in a Manifest Destiny-themed fantasy. “We can give it a try,” I said. “No promises.”

“Thanks,” he replied.

What an odd thing to say. Odd and, in a way, sweet. It reminded me of the deference and politeness in the early years with Eric.

“When was your last STI screening?” I asked.

“Tested last month. Negative across the board. You?”

“I got my results last week. All clear. But condoms anyway.”

“Of course.”

“Maybe next time,” I said, by way of a canned response that wasn’t meant to be sincere.

“There’s a next time?”

“Shhh.” I pressed my index finger against his lips.

It took a few tries for him to get inside of me. He had a fine, average-size cock, but I hadn’t bottomed in recent memory. For years, anal sex had been a special occasion, and in the coda of our relationship, Eric and I rarely celebrated anything.

Sex with the catalog model proved to be of the type that rarely happens. All of it—pace, passion, synchronization, duration—seamless, thrilling and precise. Afterward, we lay silent but awake in the sunlit room, breathing softly, shadows tucked within the rumpled bedsheets, my right leg entwined in his left. His torso was mounded and hard like fruit on the verge of ripeness; his abdomen taut but not intimidating. We were only a year apart in age, but he had the lines, freckles and moles of someone older: the burden of descending from those early humans who wandered away from the equator.

He asked questions—where I worked, where I grew up, where I’d gone to school—that felt more intimate than what had just occurred between us. I responded succinctly to everything.

“And you, what do you do?”

“I’m a lawyer. For the city,” he said. “Homeless services.”

“Well, that’s nothing to be ashamed of.”

“Most days it isn’t. Why? Are you ashamed of what you do?”

“Sometimes.”

He laughed easily and ran his fingertips across my knee, but then wanted to know if I was serious.

“When I was in college, my classes were taught by tenured professors who wrote books. People who exuded authority. People with proper offices full of shelves and plaques. People who made time to meet with their students. In my department, eight of the ten faculty members are adjuncts who earn almost nothing and have little job security. They run around the city teaching at multiple colleges, which is bad for us, bad for the students, bad for the school. In effect, I teach in a public-health program where health is of secondary importance.”

It was possible that I was being too preachy, but I felt free of the responsibility to make a good impression.

“You sound like someone who’s unhappy in his work environment,” he said after a silent bit of head nodding.

“Good lover and astute. Rare combo.”

“I’m a good lover? Cool,” he said, like an insouciant teenager, the kind that would have made me swoon in my youth. Then he turned over, almost onto me, and traced my nipples with the tip of his nose and his lips, pausing occasionally to kiss me.

“I should get going. I have a stack of student papers on my desk.”

He set his elbow onto the bed and cradled his chin in his hand. “Oh.”

“You should probably get dressed too. I can’t really let you stay here.”

“Of course.”

The catalog-model-cum-lawyer leapt to his feet with the alacrity of an athlete. I found myself feeling self-conscious and awestruck by his nudity, by a beautiful body in full relief. His thighs and calves were magnificently thick and well-defined, like slabs of stone that had been carved into being. The muscles in his back bulged subtly as he bent over to pick up his underwear and pants, and as he pulled thin, pin-striped socks over his feet. I felt, for a moment, as if I were watching my high school girlfriend’s shirtless father watering the lawn.

I turned toward a window. Gerardo’s plump succulents adorned a red-oak shelf installed at the frame’s midpoint. Gerardo isn’t only a magician in the kitchen, he’s an extraordinary keeper of plants. It’s a form of meditation that’s aided his sobriety for almost ten years.

“Should I strip the bed?” he asked.

“Nah, leave it. My friend won’t care.”

Fully dressed, he reached halfway across the bed (one foot on the ground, one knee on the mattress) for a tissue I’d left on my side. In fact, he collected all the tissues and condoms and took them to the bathroom. He was someone with manners and without germ hang-ups. When he reappeared, his mouth was a gentle grin, not an action so much as a semi-permanent state. He asked for my phone number.

“Just a one-off then?” he said, when I hesitated.

“Listen, I recently ended something.”

“You ended it?”

“Mutual, but I’m—”

“How long ago did you break up?”

“Two months—”

“Oh—”

“But we’d been together for six years.”

“I see,” he said authentically, no longer playful. “Maybe just a drink then?”

Reluctant to explain my newfound and complicated stance on love—namely, that its chances for success improve if it’s segregated by race, class, culture, political ideas, dietary restrictions—I gave him my number.

“I promise not to dial or text drunk,” he said. “I’ll call you now, so that you have my number.”

My phone rattled in my pocket.

I led him down a long, brick corridor and through the modern, angular living room, also with an exposed-everything motif—brick, beams, pipes. Gerardo had been dating an architect when he bought the apartment. At the front door, the lawyer for homeless people (or maybe he was the one who defended the city against homeless people) took my hand. He stepped toward me, placed his free hand on my back, and pressed me into him. He dipped his head slightly to account for our height disparity—three or four inches. His lips were warm and subtly swollen from their earlier efforts. Our mouths opened slightly, and I tasted a mélange of myself—saliva, armpits, cock, asshole, feet. We were no longer saying goodbye.

“You’re trouble,” I said, as I stepped back.

“Hopefully more fun than trouble.”

This was a gentle, endearing sort of audaciousness; something special, I thought. I slid my hands into my pockets, attempting to conceal my growing erection. He noticed. “My first meeting isn’t until one,” he said. “We can hang out a bit longer if you—”

“I can’t.”

“Okay. Another time, I hope.”

After he left, I stripped the bed, showered quickly, and ate something in Gerardo’s fridge that looked like chicken, but tasted like duck.

I didn’t want to go back underground. Instead, I wrapped my scarf tightly around my neck and chin and assumed a brisk pace uptown.

That night, Gerardo sent a few recriminatory texts:

“I don’t mind you ate my rabbit, but you could have put the sheets in the wash.”

“And you owe me lube!”

“White guys make you inconsiderate.”

●

Five days later, the lawyer sent three messages in under an hour. It was Sunday morning, shortly after ten. A few blocks away, the bells of the French-speaking Baptist church, filled with well-heeled Haitians, had only just ceased clanging. I was copying my antiquated music collection, one CD at a time, over to an external hard drive—something Eric had for years encouraged me to do. This tedious form of transcription had become my evening and weekend drudgery since the breakup. There would be no room for these relics in the new place, a single-salary one-bedroom not too far from the neighborhood I’d called home for the past decade—a part of Brooklyn I’d been complicit in gentrifying, which I could no longer afford.

I’d just ripped Funky Divas by En Vogue—Actually by Pet Shop Boys was next—when I heard the first text: “I’m free for the next few years, if you want to take a walk or eat something.”

Five CDs later, I still hadn’t replied. My phone again dinged: “Actually, I have a friend’s wedding in Seattle in December, but since it’s only March, we can plan ahead.”

This was the sort of charming thing that Meg Ryan or Julia Roberts encountered regularly. I slid the phone across the slick, recently renovated wood floors. In retrospect, Eric and I had fixed up our place in order to disguise our underlying issues—the urban renewal of our relationship.

3 Years, 5 Months and 2 Days in the Life of… by Arrested Development had just finished copying when the lawyer’s final text came through: “No pressure, but if you change your mind, I’ll be happy to hear from you.”

His allure and his scent lingered, like a smolder in the wee hours. A few times over the next week, I found myself reading the text messages and concocting clever responses. I found, too, that the loneliness of bedtime and dinner preparation was almost enough to overturn my convictions.

I resisted. The chances were high that this man had white parents and white friends and that I’d be explaining where I was from for the next ten years. Maybe, too, he was the kind of white person who equated race with class. Or, worse, the kind who couldn’t see the obvious link between the two. Over time, we’d learn to avoid certain topics. If I were lucky, he’d nod along and keep trying. If I were unlucky, he’d accuse me of overreacting and, secretly, I’d question his character. Eventually, an internal hierarchy mirroring the external one would settle upon us, and I’d wonder why he was getting attention or respect that I wasn’t and whether I was using his status as a shield to the world. I’d spend the remainder of my life disentangling intention from impact, lamenting that I had gone to a private university upstate instead of a city college.

Or maybe I was mistaken, blinded by cynicism. Integrated love didn’t have to bear the weight of such a grim outlook. He’d try, and I’d try, and together we might create something immersive, nurturing and revolutionary. Our love would envelop us, like a force field or a good angel with broad, unfurled cages for wings. And I’d never again have trouble hailing a cab.

●

Whenever I was tempted to call the lawyer, I contacted Gerardo instead. Each time, he responded the same thing: “#selfcare.” This was his mantra. After a half dozen times of reaching out, Gerardo told me to get a boyfriend: “This is what online dating is for. Do the work.” A few minutes later, he texted again, “Come by restaurant tomorrow. New vegan menudo on menu. Seitan = panza. I’ll intro to bartender. Gorgeous, single, Guatemalan, they/them. Late 20s. Puppy-dog type. Needs someone grown-up like you.”

I wasn’t particularly interested in taking care of anyone or in being the responsible half of anything or in having a get-to-know-you drink with someone in the middle of their work shift, but I was already half-asleep when Gerardo’s message came through. “Okay. I’ll meet them,” I texted back. I was choosing to be optimistic, instead of dwelling on the potential class implications. “I’ll swing by after the gym.”

The following morning, I awoke hopeful—I put on my good socks and a pair of snug underwear—but by the time I reached the train station, I felt a bygone disarray in my bloodstream. A swoosh of electricity traced my body, head to toe, inside and out. I recognized the sensation. I’d been accustomed to feeling it in airports, in the moments before I committed to the high-altitude terror: the necessary forgoing of my sanity, in order to escape, explore or experience life. Or maybe it was the reverse: not the anxiety of seizing life, but the disappointment of it passing me by. I thought of the trips I hadn’t allowed myself to plan. I thought, too, of the time I’d panicked at LAX and missed my connecting flight to Japan. It was an inconvenient and expensive change to my itinerary, but it resulted in a fun stay in Los Angeles, where I was able to regroup and shore up my courage to fly to Tokyo two days later.

As I held my place on the crowded subway platform, I closed my eyes and concocted a serene setting—a steady rivulet at my feet, snowcapped mountains in the distance—but it wasn’t enough to overpower the striking unease. I tried next to imagine my fears as a two-dimensional rendering that I could fold up to the size of a business card and stuff into my breast pocket. When this, too, failed to calm me, I dug into my bag for headphones, selected Dreaming of You, Selena’s first posthumous release, and skipped straight to the album’s second half.

The train rolled into the station, and I considered for a moment remaining on the platform, but when the doors opened, I rushed in alongside everyone else. I nabbed an empty seat by a window and crossed my legs, casually cradling one knee against my chest. The doors closed, and we entered the tunnel. I filled my lungs and disengaged my shoulders. The anxious moment passed.

The train snaked slowly; then, at a faster pace. As we rounded a bend, I glimpsed into the car behind mine. There he was, the catalog model, sandwiched between two much shorter people: the illusion of a giant. He wore standard white headphones, and his hair was parted neatly to one side. His face was as handsome and mirthful as it had been when we’d said goodbye. He looked straight ahead, but I couldn’t see what had caught his stare. Before the train straightened out, I was momentarily in his sights. I turned away too quickly to be anything but obvious. The banner of advertisements above—a vocational college, a storage company, a PSA about smoking and oral cancer—kept my attention until we reached the bridge. Once there, the car filled with a light that altered the panorama, illuminating the morning glares of the undead—seated, standing, gripping, business casual. I eyed a stain on the floor that was immediately darker because of the contrast. It was bigger than a large coin, but not by much. It had once been gum: vibrant, bright-colored, probably pink; now, dull, lifeless and permanent. Certainly an easily explained metamorphosis, it has nonetheless always puzzled me. As the natural light receded from the car, my focus did too. The train was decelerating. I had a few stations yet to go. I kept my gaze low and searched the car for something else to hold my attention.

Art credit: Louis Fratino, “Dolphin Street,” Oil and crayon on canvas, 30 × 24 in., 2017 (top image); “Grapefruit Breakfast, 2017. Oil and crayon on canvas, 40 × 30 in. (second image) © Louis Fratino, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.