Listen to an audio version of this essay:

So we see that it is in everyone’s nature to strive to bring it about that others should adopt his attitude to life; and while all strive equally to this end they equally hinder one another, and in all seeking the praise or love of all, they provoke mutual dislike.

—Baruch Spinoza

[A DATA POINT IS BORN]

I grew up along the Northern California coast and went to college there. I enjoyed hiking and philosophy, especially together. I had long hair and a goatee, and no matter the weather wore a flannel shirt and long shorts. I’d often hike alone to a remote lookout and spend the day reading Heidegger or Plato, along with some Romantic poetry. These interests eventually brought me to graduate school in Chicago. This was my first sustained immersion in an urban environment, and it changed me.

I have a vivid recollection of a particular moment. It may or may not have actually happened, but I remember it nonetheless. Book in hand, I was walking along the lakefront near the Loop. I planned to read facing the water. Instead I stood there for a while, looking at the lake, looking at the city, my body perpendicular to each. Eventually, I walked toward the skyline, turning my back on nature. Now I am a professional social scientist.

Sometime after that I went to my tenth high school reunion. I had short hair and wore a long black overcoat. A former classmate observed: “You’ve changed.”

From a few sparse paragraphs of flat prose, you now have an image of me. With minimal information, largely about my tastes, you will have slotted me somewhere in reference to you: somebody to get closer to, somebody to get away from. You will likely also have an image of the sort of people I prefer to be around. And you’ll probably be right.

You might be too polite to say it out loud, but behind this positioning is a set of judgments about me, issued almost involuntarily: cliché urban cosmopolitan; wannabe intellectual; self-important navel-gazer. You might also have thought some nice things. Either way, your perception of me is far from neutral: it expresses your tastes. You are judging me, but in doing so you are also judging yourself—as the sort of person who would think such things about somebody like me. Depending on how you do that, you move yourself closer to or further from me.

Like so many iron filings falling into place around an electromagnet, we align ourselves with those who like what and who we like and distance ourselves from those who do not. The technical term for this concept is homophily, “love of the same.” Homophily—and its less-mentioned opposite, heterophobia, dislike of the different—underlie the theory of social order that has come to govern much of our lives.

[LOL, OR: THE WORLD CLOSES IN ON ITSELF]

This theory is expressed in the principle of the like button: you like this, I like this, we like each other; we are friends. You don’t like this, I do like this, we don’t like each other; we are not friends. You liked her, but she liked what he said; I don’t like him; I don’t like you. I need to get away from you, you need to get away from me. Call it the “Logic of the Like.”

There is an immense power to this way of thinking. For social media companies, the Logic of the Like distills the seemingly ungraspable complexity of social life into a few simple processes, and allows an entire social edifice to be built up by iterating them. As we rate and approve, upvote and downvote, we sort ourselves into clusters. Recommendation systems in turn feed us content similar to what is popular with “people like me,” creating incentives for new products to approximate, with slight variations, what is already popular.

For social researchers, the creation of technologies of communication and interaction governed by this logic presents an irresistible opportunity. In ways that seemed impossible just decades ago, we can now map the invisible threads of liking and disliking that hold the world together and organize it into clumps and camps. The books you like on Amazon—from Hemingway to Hillary—tell us not just what you like but who you stand with and against, and modern computational techniques allow us to compress millions of everyday judgments into a single graph that plots each of us into our assigned place.

The Logic of the Like has been so useful to social media companies and social researchers because it is a form of social life that taps into and intensifies powerful human passions. And indeed, to all of us, the Logic of the Like offers a seductively thrilling form of democratic world-building. To enact it is to participate in creating an order that stands on nothing more than ourselves, our own tastes and interests. No central authority determines what or who we should like, or not like. The kind of power traditionally enjoyed only by media executives or emperors, of raising or lowering the stature of some private person by placing them before the eyes of the public, now belongs to us all.

Meanwhile, seemingly insignificant expressions of taste—do you like or dislike these beans or that cookbook author—become laden with the weight of the world. Every like is itself and more: the beans and the social meaning of the beans are contained in the same act. You fight your battles, but the contest is really about the shape and tilt of the battlefield itself. This is a never-ending story: if you drop out, so too does your taste profile, and the interaction order becomes that much more alien to you than it was before. Each like demands another like; each like is more than this like. To present an easily accessible pathway to being more and more-than yourself—in a word, to transcendence—is perhaps the root charisma of the Logic of the Like.

And yet, as new communication technologies expand and come to structure more and more of our interactions, it is hard to avoid feeling there is something lost in living by the Logic of the Like. We reach for terms like “homogeneous,” “simple” or “flat” in order to express some truth about life in a world reduced to vectors of attraction and revulsion. Homogeneous, because of the tendency to steer ourselves toward others who already view the world as we do. Simple, in that complex emotional life is compressed into a single scale with only two sides: like and not like. Flat, because it seems to reduce the depth and texture of life.

But these terms fail to capture what is perhaps the most potent feature of the Logic of the Like, which is its seeming inescapability. It is similar to Thomas Hobbes’s theory of religion. We create a God whose needs and desires in turn come to control us. And the Logic of the Like is a jealous God. It admits nothing outside of itself, even its own negation. For example, suppose you decided to reject homogeny and seek out difference, contingency and surprise. A noble pursuit, perhaps, but easily assimilable: “I think we should expose ourselves to difference” is exactly what someone like you would say. It is a self-organizing system but also a self-enclosing one.

Or suppose you rejected simplicity and instead of only using the like button you used the sad faces and angry faces and surprised faces (“reactions”). Or even better, imagine if I were a better writer and could express in rich detail the full range of emotions I felt every step of the way as I stood there between Lake Michigan and the Loop, poised on a knife’s edge, hovering between nature and culture. A more complex picture, to be sure, but not a problem for the Logic of the Like. We count up the evaluative words I use, assign each of them a value as a positive or negative sentiment, and score my experience according to their sum total: now he likes cities more than nature. More complicated techniques can sidestep the requirement to reduce my statements to a single scale, and classify me according to how similar the combination of words I use is to other people’s descriptions of natural and artificial objects. The end result is the same: I’ll be positioned in a mass of data points alongside others who respond to the world as I do.

Or suppose you decide to leave the flatlands of the Logic of the Like and seek out the depths of experience in great literary works. For instance, instead of, say, spending an afternoon thumbs-upping TikTok videos, you sit down to read Flaubert’s Sentimental Education and find yourself carried away. Surely there is a realm of aesthetic autonomy here? No, the door remains closed. According to the Logic of the Like, the desire for aesthetic purity is itself a particular type of interest: an interest in appearing disinterested. And just as surely will you tend to find yourself drawn to people who share that interest, and repulsed by those who do not. There is no exit.

[THEORIST OF LOGIC]

If there is one theorist who, as much as any other, articulated the Logic of the Like, it is the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. In fact, Bourdieu advanced a reading of Sentimental Education that sought in it both an expression of the latent class structure of nineteenth-century Parisian society revealed by the tastes of its characters and of the strategies by which literary publics use claims to aesthetic autonomy to advance their own social positions. While this did not endear him to traditional literary critics and lovers of literature, it does point toward his value as a guide into the inner logic of the Logic of the Like.

Bourdieu was born in 1930 in a remote village in southwestern France and grew up in a family of modest means. A person of remarkable talent, creativity and drive, he rose through the pyramid of French academia, culminating with his election to the Collège de France in the 1980s. His humble origins as an outsider who scaled the heights of the social and career ladder provided the background, in his own telling, for his ruthless depiction of Parisian high society as illusory refinement masking systems of domination and control.

Though he was trained in philosophy, Bourdieu’s interests turned toward anthropology and sociology early in his career. At the time, the ascendant approach was Claude Lévi-Strauss’s structuralism, which promised empirical and scientific answers to traditional philosophical questions about the nature of meaning, culture and value. Bourdieu was drawn to the structuralist attack on purely theoretical reflection, and received a push in that same direction while stationed in Algeria in the late 1950s as part of his military service. There he conducted fieldwork to which he would return throughout his career. But this work also led to key theoretical insights that eventually caused him to reject Lévi-Straussian structuralism.

The central insight that led Bourdieu away from structuralism concerns the concept of social rules. Traditional structuralist accounts offer rich description of the systems of rituals and symbols by which a person attains honor, for example, within a given culture. Bourdieu argued that such accounts yield little insight into how people act. This is because people routinely play seemingly established conventions off of one another, or adhere to such rules for the purpose of hiding their own concrete interests. There are the rules, and then there are the rules. Indeed, Bourdieu observed that elaborate rituals for demonstrating a person is not greedy and cannot be bought off have the effect of advancing and profiting that person, while reproducing their social position. This need not occur consciously—in fact, it cannot, according to Bourdieu—but instead arises through ingrained patterns of perception and behavior, the “habitus” individuals imbibe through their early childhood upbringing.

This same thought informed Bourdieu’s critique of Max Weber’s sociology of religion. Weber had famously argued that “religious rejections of the world” had transformative social potentials. While Weber recognized that religious movements emerged at particular social and historical moments, he took seriously the substantive values of religious teachings. “Sell all you have and give to the poor,” “the mind is freed from its accumulations, it has reached the cessation of desire”—these and similar prophetic renunciations are for Weber not reducible to covers by which social groups advance their standing. In rejecting “the way of the world” as it is, they also rejected the us-versus-them of existing kinship and tribal affiliations and made new forms of community and solidarity possible. Bourdieu, denying what he viewed as Weber’s sentimental idealism, instead reinterpreted the words and deeds of prophets as so many moves in the game within their local relationships and power struggles—their religious “field”—which expressed habituated “strategies” to accumulate followers and attack rivals.

Bourdieu began by directing his critical social theory toward the distant past and at “exotic” non-European peoples, but he did not end there. Bourdieu brought his weapons home, turning them on French society and culture with a vengeance. This culminated in his most famous work, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Published in 1979 and based largely on a national survey of cultural tastes, as well as snippets from newspapers and personal observations of fashionable society, Distinction argued that what seem like our most personal and private sensibilities are produced by and in turn reproduce our class position. Our opinions about what food tastes good or bad, what music to play at a social gathering, what pictures to hang on our walls—those judgments position us vis-à-vis one another, and those who accumulate more “cultural capital” not only tend to dominate the game, they define what it means to play it well. This is “the real cultural game” played out by the “privileged in privileged societies, who can afford to conceal the real differences, namely those of domination, beneath contrasting manners.”

On the basis of this analysis, Bourdieu developed a more subtle class theory than his Marxist predecessors. Instead of placing all occupations on a single scale from poor to rich, Bourdieu could distinguish between professors and plumbers. Even if the two might earn similar amounts of “financial capital,” the former possessed substantially greater “cultural capital,” buying them access to social domains off limits to the latter.

While this schema may mark a real scientific advance, Bourdieu did not aspire merely to academic understanding. His is a contemporary variant of the perennially seductive impulse to debunk. In this tradition, you identify those aspects of the world that have some kind of aura around them, and you rip the halo off. Voltaire did this for politics: behind the purple robes are mere mortals asserting their power. Feuerbach did this for religion, which he said was nothing but the projection of human needs. Marx did this for the economy: the mystique of free markets and private property is a mask by which some dominate others. Bourdieu, too, is a debunker. This is why he started with poets, novelists and aesthetes—those who were still wearing their halos. By transforming their activities into forms of positioning, he brought them down to earth, exposed them as inescapably determined by “the ways of the world,” and demystified their claims to be otherwise.

[THE NORMALIZATION OF A SCANDAL]

Bourdieu’s analysis was initially seen as scandalous, and it has faced harsh criticism from sociological theorists. The most persistent charge has been that his theory is highly deterministic and reductive, leaving almost no room for growth or transformation, while assuming that any difference between groups—including in food or music preferences—is ipso facto motivated by a desire to maintain power differentials. It is one thing to show, for example, a correlation between education and liking Sufjan Stevens; it is another to demonstrate that liking Sufjan Stevens has the effect of maintaining social hierarchies, and yet another to prove that those who like Sufjan Stevens do so in order to maintain those hierarchies. One of Bourdieu’s most strident French critics referred to collapsing the distinctions along this chain of reasoning as a form of “sociological terrorism.”

To the extent that Bourdieu did attempt to respond to his critics, he was never able to develop a compelling theory of social change beyond new entrants seeking to displace incumbents or to offer insights into the nature of social or artistic creativity. To do so would have required backtracking on his critique of Weber and admitting there were types of action that were not best described as mainly instrumental or strategic.

There is no shame in advancing a novel but incomplete social theory, and such critical debates are the normal stuff of intellectual discourse. What is striking, however, is that, whatever its weaknesses, Bourdieu’s highly contestable and partial theory has over time come to describe aspects of our social life with frightening accuracy. This is not because he refined the theory in any notable way; rather, the parts of the social world that best embody it have grown to increasingly structure how we interact.

The desire for recognition, and the wish to win the approval of highly regarded personages, is far from new. But social media and online rating and streaming-recommendation systems have hypercharged these desires and removed obstacles to giving them free rein. They did so in part by adapting and commercializing concepts and techniques forged by the pioneers of modern market and social research. Like a virus jumping from the lab into an environment in which it thrives and spreads, the Logic of the Like in this way escaped the confines of academic research reports, found a setting to which it was highly suited, and in turn came to dominate that environment and those of us who occupy it.

[PRACTICE OF LOGIC]

Facebook added the like button to its platform in 2009, but the concept of tracking emotional responses to flows of information is older. Together with other innovations such as the “focused group-interview” and the concept of homophily itself, mid-century Columbia University sociologists Paul Lazarsfeld and Robert Merton devised like and dislike buttons as a novel data-collection technique. Lazarsfeld and Merton showed videos to regular people (such as housewives being encouraged to cook with less meat) and gave them buttons to record their emotional responses. They followed these with focused interviews to register what was driving their choices, in their own terms.

Lazarsfeld, Merton and their colleagues identified fundamental societal shifts that would only later be codified by Daniel Bell as “the coming of post-industrial society” and a “revolution in sensibility.” Their like buttons were part of a package of innovations designed to tap into the rapidly changing social world the Columbia sociologists saw emerging around them. These changes included, among others, the rise of national media, credit cards and cars, which fused with cultural changes—most notably the expansion of bohemian and New Age philosophies—to support a broader ethos of personal self-expression and authenticity.

Even so, their like buttons remained rooted in an older, industrial, one-way relationship between company and consumer, researcher and subject. Merton and Lazarsfeld brought people into a room, showed them some videos, gave them buttons to push, asked them questions—and then everybody went home.

To understand how the like button has migrated in the 21st century from the lab to life, we can look across the Atlantic, where Bourdieu himself was working with other French researchers charting similar trends and also developing methods designed to reveal the operations of the Logic of the Like in everyday life. A notable pioneer of what would become modern data analytics was Jean-Paul Benzécri, one of Bourdieu’s lifelong friends and classmates at the École Normale Supérieure. Bourdieu himself remarked: “Those who know [Benzécri’s] principles … will grasp the affinity between this method of mathematical analysis” and Bourdieu’s own theory of social order.

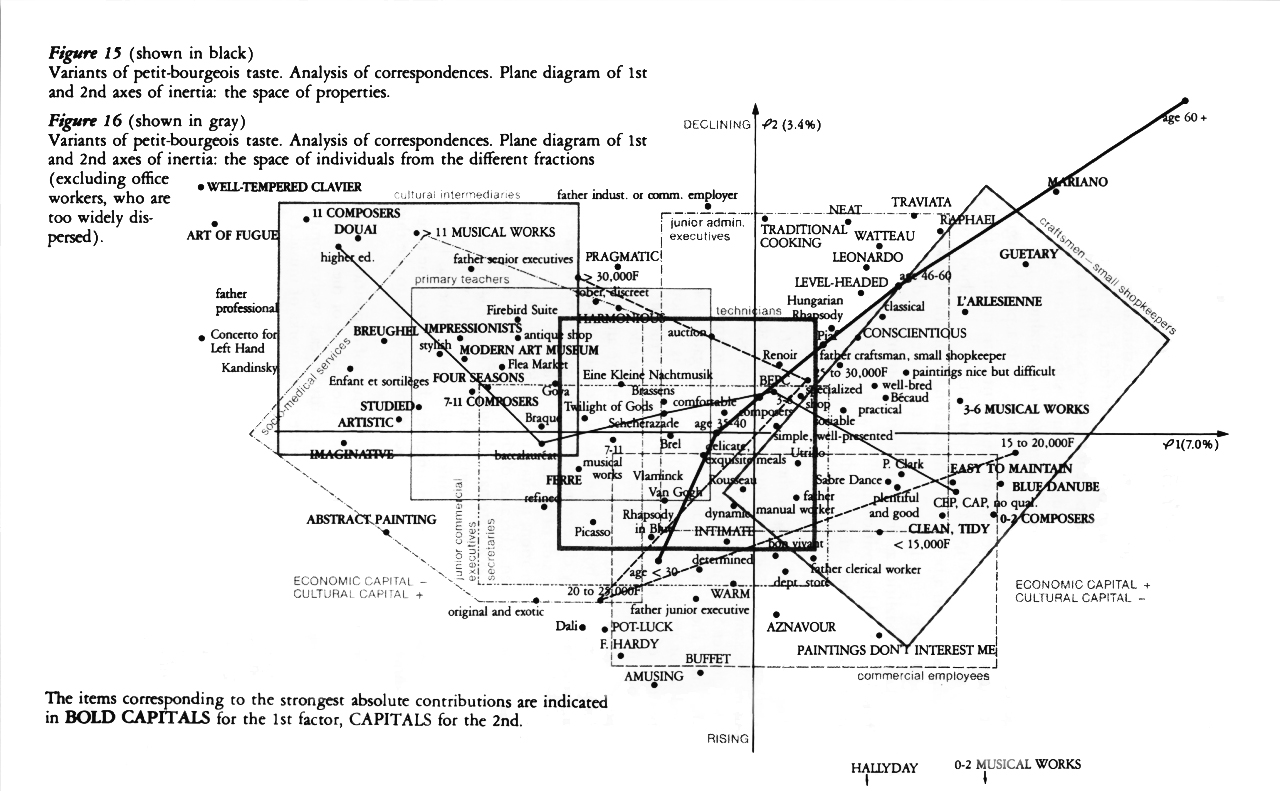

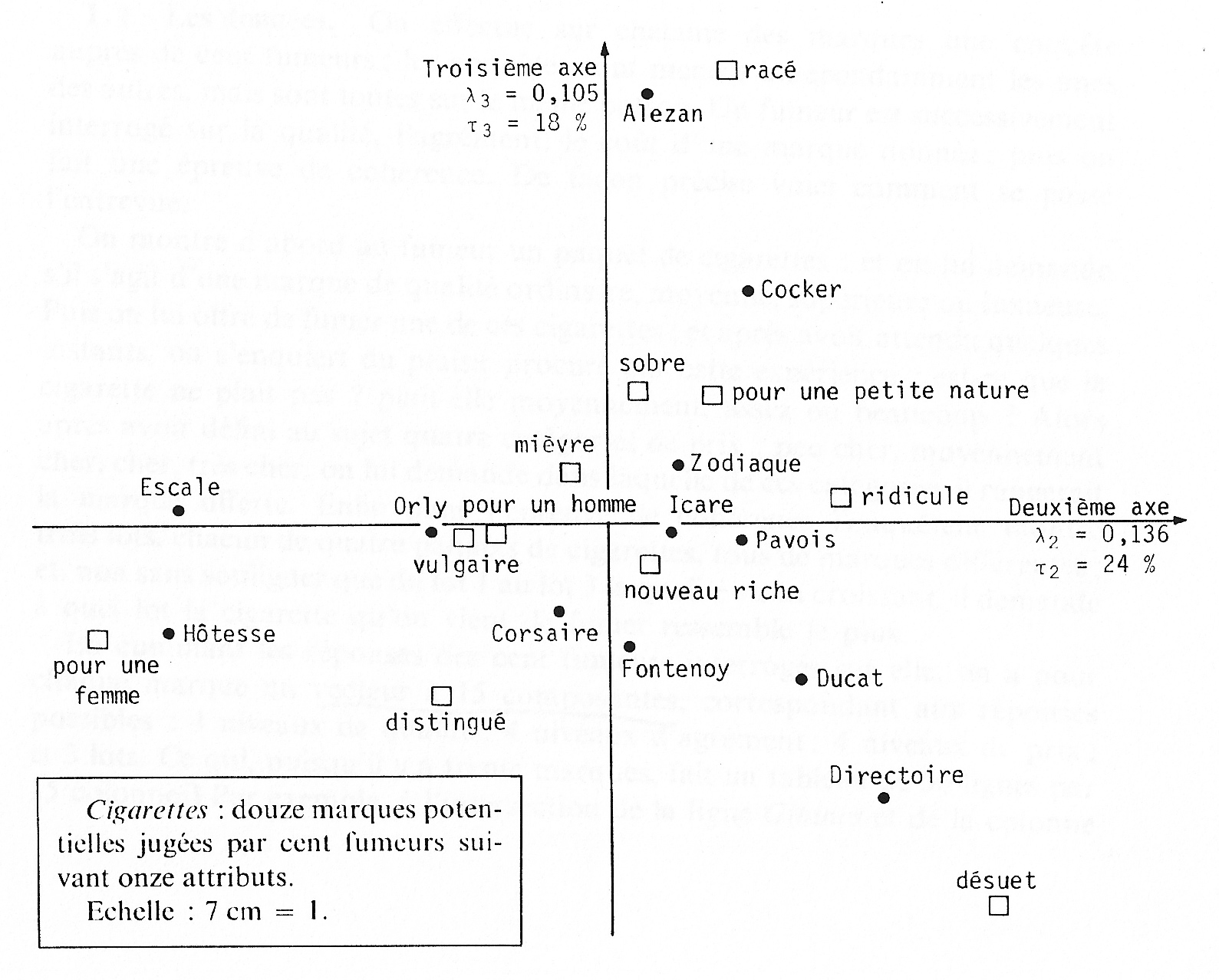

These methods enabled the analyst to represent social life precisely as Bourdieu had theorized it, as a space of positions and a game of positioning. Benzécri promoted a family of approaches that would later be called “Geometric Data Analysis” (or GDA) or “factorial analysis.” The basic impulse of geometric data analysis is to devise techniques for locating and visualizing individual cases on a diagram, where their positions are determined by the similarity and difference of their responses when compared to one another and the most distinctive characteristics within a population become the most visible. They afford a view of the social world in terms of groups held together by the few items that they like the most and the least, clumping people at the extremes of their taste profiles. The clumped clouds of points of geometric data analysis were the physical manifestation of a distinctive view of the social world crystallized in the Logic of the Like.

Though techniques of geometric data analysis were widely known, their use outside of France and parts of Europe was relatively uncommon in Anglophone social sciences until the late 1990s and early 2000s. Computer scientists and market researchers began to adapt and update them in combination with other emerging techniques utilizing similar principles around the same time in developing recommendation and targeted advertising systems, attracted by their ability to reduce the complexity of large high-dimensional data flows generated by internet activity and to feed users the types of items liked by people similar to themselves. Social media firms, for their part, used iterations of these techniques to make predictions about what content would most reliably and predictably attract the most attention from users. In the process, they discovered that, as computer scientist and AI researcher Stuart Russell puts it, the solution is not “to present items that the user likes to click on.” Rather, “the solution is to change the user’s preferences so that they become more predictable.” The most predictable users, it turns out, are those with the most extreme or distinctive views. In iteratively feeding users the most extreme items that most distinguish them even from highly similar others, the algorithms learn that the best way to maximize their own reward—more likes—is to heighten the tendency in their environment—their users’ minds—toward extreme positions. Social media companies more accurately predict likes by installing the Logic of the Like in our minds as our primary conception of social order.

Theory and practice converged, yet in doing so the theory moved from the background to the foreground. For Bourdieu himself, uncovering the Logic of the Like was to penetrate beneath the surface. Indeed, in using Benzécri’s factorial analysis methods to uncover clusters of individuals held together by the latent principles of distinction, Bourdieu believed he had found the modern analogs to the clans and tribes of his structuralist forebears from Durkheim and Mauss to Lévi-Strauss. Today, though, no theory is necessary to understand social life in this way: in the age of social media, it comes naturally to us.

[LIFE ON EARTH]

The attraction of the Bourdieusian style of analysis comes in large part from bringing the angels down to earth: armed with empirical data and analysis, it appears to be insulated against idealistic delusions about human behavior. But what does it mean to live on the earth?

Bourdieu’s earth is the dark inversion of the Kantian heaven it imagines. If the angels are disinterested and disembodied creatures—somehow above and beyond the pursuit of power and position—then life on earth is the opposite. Bourdieu resisted drawing any direct normative lessons from his social theory. Still, insofar as it seems to imply one, it is that if we are to face up to social reality and be honest with ourselves about its real stakes, we may as well learn to play “the real cultural game” well—that is, ruthlessly. Of course this implies too that Bourdieu’s books are themselves a part of that game, only played, as he put it, in a more “self-reflexive” way. Ultimately, his sociology reaffirms the inescapability of the Logic of the Like. It is a form of negation that leaves you nowhere else to go and nothing else to do. Power and position are what is left when there is nothing else to live for.

The escape from the infinite loop of the Logic of the Like, then, must begin with an appreciation for the richness of human experience. Bourdieu often described himself as a theorist of practice, a sort of pragmatist who believed that practical exigencies trump high-minded ideals. If we turn to other self-described theorists of practice, however, we find a contrasting assessment of what practical life on earth entails. John Dewey stands as a powerful case in point.

Bourdieu and Dewey seem to share much in common and are often discussed together as incisive critics of disembodied reasoning. Yet their pragmatisms could not be more different, most obviously in their intellectual style and affect but also in their substance. If Bourdieu’s pragmatism leads to a hard-edged cynicism, Dewey’s resulted in a more open-ended faith in the potential of democratic progress.

When Bourdieu proposed his own version of democratizing culture, he meant making the cultural styles of elites available to the masses through reforming their habits and, for example, providing more interpretative support for their encounters with high culture (placards in art museums and the like). In effect, democratization for Bourdieu meant expanding the number of players in the status games of the privileged. For Dewey, on the other hand, democratizing the arts was important because it would enrich the lives of numerous people and build our capacity to communicate across social divisions. This experiential focus was crucial for his vision of a pluralistic democracy—one where all those affected by a problem have some say in how to respond appropriately.

Dewey acknowledged that we begin from categories, classifications and positions, but his entire philosophy was set against the notion that those classifications could be the end of social and political life. In his view, rather, there was no end, only temporary “ends-in-view,” and life—real practical life—was an endless process of testing them. Art, in his view, is “more moral than moralities” because it not only aims to enforce conventional goods and ideals but discovers and realizes new ones.

Because he saw individuals’ fulfillment as being intimately tied to their social environment, Dewey’s pragmatism was geared toward creating practical conditions for realizing the proposition that “the powers of a man are not fixed, but capable of modification and redirection.” Accordingly, he was a deep critic of any structure of thought or interaction that pushed us in the opposite direction—toward ways of interacting that make it more difficult to undergo “the growth of character and conduct” that comes from opening oneself up to new possibilities that arise in the course of one’s activities. The competing visions of life represented by Dewey and Bourdieu could be described as the growth and enrichment of experience versus the logic of interested practice. How do we evaluate them? The pragmatist answer is that we put them to the practical test: try them, entertain their implications and see what happens. We have seen the practical maxims of the Logic of the Like and where they lead: to Spinoza’s “they provoke mutual dislike.” Rather than sketch out a Deweyan alternative in the abstract, therefore, I would like to suggest that a bit of pragmatist practical wisdom may be found in a homely maxim of everyday life: don’t judge a book by its cover.

[COVER STORY]

I don’t know the history of the phrase, but I’d like to imagine that it was a hard-won outcome of collectively learning to deal with the massive proliferation of books as distribution technology improved, and their capacity to spread information, good and bad. I imagine that for a time simply seeing something in print, on pages bound between two covers, could give the allure of authority, and that this would be a recipe for disruption and division. “Don’t judge a book by its cover” is a cognitive truism but a practical challenge, the truth of which comes from living it, not knowing it.

Today we have metadata and data in place of covers and books. Data is the real thing, the information we care about. Metadata is additional information that accompanies the important stuff. For example, in a conversation the data are the things you say, or more properly the meaning of your words as they pertain to the experiences they make evident. Metadata could include aspects of your background, such as your age or religion, or also your workplace, or the types of caffeinated beverages, TV shows and vegetables you like. Metadata is like the cover of a book. If you have lots of covers of lots of books, you can probably get reasonably good at predicting from the cover what is in the book. Similarly, with enough metadata about you, it is possible I might get pretty good at predicting what you will say or do based solely on the metadata.

There are many useful applications of this ability to make predictions based on metadata. Does this give the lie to the saying that you should never judge a book by its cover? It does if it means that the meaning of a cover is exhausted by its function as a signpost or indicator of what you will find inside the book. In that case, with enough metadata, and enough data, enough books and enough covers, you might conceivably never need to read a book again. Similarly, you’d never need to talk to anybody again. You’d know what they would say already. In the Logic of the Like, the distinction between metadata and data collapses.

But that does not capture what it means for a book to have a cover. The cover is also a ritual boundary, like changing into a uniform before starting a karate class or saying a prayer before entering a sacred space. There is an inside and an outside. The cover indicates that you are about to start something that will have its own experiential process of buildup and completion, distinct from the world outside. It is a warped space in experience: there is depth to it. It needs to be penetrated, and some kind of essential secret needs to be revealed. To understand it is to go through it. This means there is necessarily something held back that emerges in the process of engagement as it builds towards its own internal climax—a world with an inner and an outer, a surface and a depth, a front and a back, a manifest and a latent, a seen and an unseen. In Dewey’s terms, this is the movement from “experience” to “an experience.”

If we imagine that metadata is all we need, we are imagining a world in which there are only covers and no books, experience but no experiences. There might be pages, but every page is just another cover. It would be covers all the way down. You can read a book this way, extremely closely, but it will never escape the Logic of the Like. To do that, you need a book you can’t judge by its cover.

[JUDGE NOT]

In the Logic of the Like, clicking the like button amounts to what Dewey referred to as juridical “verdicts.” A verdict seeks to lay down the final word about what the meaning of an event consists in, on the basis of an authoritative touchstone. They are necessarily bound up with the exercise of control. Hence the focus of Bourdieu and his followers on gatekeepers who attempt to protect the power to classify. The wisdom of “don’t judge a book by its cover,” by contrast, comes closer to Dewey’s notion of judgment. Rather than being the most fundamental dimension of human relation, judgments (likings and not-likings) for Dewey are just one part—albeit an important one—of his broader theory of experience and practice. A well-placed “I like it” or “hmm, not sure about that” can help to move a conversation forward, or in a different context break it apart before it reaches its full potential. In either case, Dewey’s focus is not about how the judgment reflects back on the class position of the judger, but rather about the role of making or reserving judgments in serving or stymieing the buildup of an experience.

Dewey’s way of thinking has implications that extend beyond interpersonal dialogue. The sweeping social significance of the capacity to periodically suspend judgment, to even momentarily exit the Logic of the Like, is evident in sociologist Christopher Winship’s account of the emergence of Boston’s TenPoint Coalition in the 1990s.1 The TenPoint Coalition is a group of African American ministers and laypersons that partners with police with the goal of reducing violence. It played a key role in the “Boston Miracle,” during which violent crime in the city was dramatically reduced. The partnership, however, was highly unlikely given the history of deep tensions between police and local Black communities in Boston. Indeed, prior to its inception, through a series of interlocking and escalating events, relations between community members and police had hardened to the point that communication had stalled, mistrust was rampant and they were figuratively “at each other’s throats.”

Two well-established, conflicting interpretations of the situation had emerged: one blamed moral decay, the other blamed discrimination and racial oppression. Police and ministers largely aligned on one side or the other. Each simultaneously held clear understandings of their own roles in the neighborhoods: police as “effective fighters of crime” and ministers as “guardians of the church” offering a “sanctuary from the ‘war.’” As events unfolded, both interpretations became unstable. Various scandals, often around hyper-aggressive tactics, undermined the public legitimacy of the police and their generally reactive approach to violence. A stabbing and shoot-out among gang members during a funeral service at a Baptist church for a youth murdered in a drive-by shooting challenged the moral authority of the ministers and the sanctity of their churches. “The message was clear—if the church was not going to deal with the problems of the streets, those problems would enter the church.” The authority of both police and ministers was in doubt, but neither had a clear sense of what to do. They occupied the same space, held similar goals of “dealing with the problem of youth violence,” but the commitment was parallel, not shared in a joint project.

Faced with this situation, the ministers tried something remarkable: they began to wander through their neighborhoods, in what Winship calls “purposeless engagement.” In this way—by temporarily suspending judgment while continuing to act—the ministers allowed a situation that had congealed into clearly delineated, interconnected but noncommunicating camps to loosen up and admit new possibilities. The ministers literally did not know what they were trying to accomplish. “All they knew was that they were called by God to be present.” They would bump into gang members and police and strike up conversations, but without a clear agenda or plan, even a plan to come to the table and negotiate: “There was no table in the story.”

Police and ministers found in the process that they depended on one another. As Winship summarizes, “For ministers there was the possibility that they would have to deal with violence directly. For the police there was the danger that their actions might lead to charges of racism and discrimination.” This mutual dependence created the potential for a shared interpretation of events they had undergone together. This was not an understanding that aligned at most or even on very many points, but it provided enough of a platform to reinterpret past events as instances of jointly achieved success, which in turn laid the basis for an informal but shared sense of the situation from which more formal partnerships and negotiations could occur. These involved gang, school and reentry forums, as well as the possibility to have meaningful dialogue about how to deal with difficult and potentially sensitive issues as they arose. The sociologist’s account in turn carried the experience into a new medium, as would films or songs, in which its meaning continues to evolve as it circulates more widely as a model for others to experiment upon and extend.

Faith in the possibility of renewed experience in turn enabled a broken situation to begin to knit itself together. Suspending judgment is not necessarily a cop-out. In fact, in situations where the demand to issue final verdicts has arrested the growth of experience, it can be an astonishing act of courage, so beyond the scope of the Logic of the Like that it can jar us to open the book and allow the story to begin anew.

[THE VIEW FROM THE FERRY]

Dewey’s philosophy, despite its undercurrents of melioristic idealism, is a hard teaching. On the model of the Logic of the Like, we may gravitate toward those who share our likes and away from those who do not, and delight in experiencing ourselves as fitted to one another, whether as allies or opponents. For Dewey, if interaction is to grow into participation, it only grows when there is a problem. Without facing the discomfort of encountering others who do not see what I see as beautiful, true or good, there can be nothing meriting the term democracy. We may thus reverse the heterophobic dictum of the Logic of the Like from “who sees this as beautiful, let him join with me” to the Deweyan injunction “who does not see this as beautiful, let me open myself to them.”

Consider Dewey’s own description of various ways of experiencing New York City from a ferry. Some regard the ferry as a “trip to get them where they want to be.” Others let their “thoughts roam to the congestion of a great industrial and commercial center” and draw conclusions about “the chaos of a society organized on the basis of conflict rather than cooperation.” Still others approach the city “esthetically, as a painter might”: “The scene formed by the buildings may be looked at as colored and lighted volumes in relation to one another, to the sky and the river.” Encountered in this manner, the scene presents itself as a “perceptual whole, constituted by related parts. No one single figure, aspect, or quality is picked out as a means to some further external result which is desired, nor as a sign of an inference.”

I imagine a latter-day Dewey riding a digital ferry, approaching the tumult of our contemporary online metropolis. Some see it in a utilitarian way, a new economy with immense commercial opportunities—a way to get from here to there. Others see it moralistically, as a congested field of conflict and contestation in which cooperation seems impossible, and ruminate on the descent of society into chaos. I wonder what it could mean to take the view of the Deweyan painter of modern life and view it as a creative process whose meaning grows as problems and solutions iteratively unfold. Online tumult would be more than a sign of the devolving or improving state of society, or a means to some further result desired above or beyond it. It would instead constitute the inevitable problem-phase of any shift to a new communicative medium. We are not the first to do so, and we will not be the last. Plato worried deeply about the consequences of writing, and adapting to the new forms of interacting it created was neither easy nor smooth. In Dewey’s words, “If … evolution were supposed to be all in one direction there would be no seriousness in life. It is only in the pressure of constantly new difficulties and evils that moral character adds new fiber, and moral progress emerges.”

What this would mean in our contemporary “difficulties and evils” is of course not entirely clear, and in any case would not happen on its own. It is a problem of collective learning and action, of democratic control over the means of communication. One can find emergent conversations about various technical and regulatory interventions. For instance, some imagine a “do you really want to post/like/share that?” prompt, similar to the now standard “do you want to save that?” Think how many files you deleted by accident before the latter became standardized; if the former could add just a moment of mediation and meditation between impulse and action, the effects could be substantial. Or it could be as straightforward as taking Kanye West’s advice and removing like buttons and follower counts.

Others envision more proactive changes, such as periodically being randomly assigned the feed or a set of followers from somebody else, or some subset of them. They would see the world through your eyes, you through theirs, and we would build into the digital world some demand to take account of the experiences of those to which we might otherwise be blind or not purposively choose to encounter. Regulatory changes could potentially achieve similar results, such as imposing on social media companies a new version of the FCC’s old “fairness doctrine,” which required holders of broadcast licenses to present controversial matters of public concern in a way that was honest, equitable and balanced.

These and other similar proposals are intriguing thought experiments, but the Logic of the Like is not only an engineering or administrative problem caused by social media in a way that could be straightforwardly “fixed.” It is also a problem of action, and therefore of ideas. To intelligently develop the seeds of an alternative requires imagining our social life in ways that go beyond the concatenation of affirmations and negations.

This is why articulating the divergent visions of social life in Bourdieu and Dewey is more than an academic compare-and-contrast exercise. To use the prophetic language of Max Weber in “Science as a Vocation,” it clarifies the fundamental meaning of the choices before us. “You serve this god and you offend the other god when you decide to adhere to this position.” The Logic of the Like or the open-ended growth of experience? Bourdieu or Dewey? As with Weber’s clash of the gods, “it is necessary to make a decisive choice.”

Art credits: Johnathan Welsh, “Like Mountain Morning,” acrylic and oil on canvas, 40 × 30 in., 2019; “Stay Tuned (Torch), acrylic and oil on canvas, 56 × 56 in., 2018; “Like Island,” acrylic and oil on panel, 20 × 20 in., 2019. All images courtesy of the artist. @johnwaynewelsh.

Graphs from Pierre Bourdieu’s Distinction (1979) and Jean-Paul Benzecri’s Data Analysis (1973).

Listen to an audio version of this essay:

[A DATA POINT IS BORN]

I grew up along the Northern California coast and went to college there. I enjoyed hiking and philosophy, especially together. I had long hair and a goatee, and no matter the weather wore a flannel shirt and long shorts. I’d often hike alone to a remote lookout and spend the day reading Heidegger or Plato, along with some Romantic poetry. These interests eventually brought me to graduate school in Chicago. This was my first sustained immersion in an urban environment, and it changed me.

I have a vivid recollection of a particular moment. It may or may not have actually happened, but I remember it nonetheless. Book in hand, I was walking along the lakefront near the Loop. I planned to read facing the water. Instead I stood there for a while, looking at the lake, looking at the city, my body perpendicular to each. Eventually, I walked toward the skyline, turning my back on nature. Now I am a professional social scientist.

Sometime after that I went to my tenth high school reunion. I had short hair and wore a long black overcoat. A former classmate observed: “You’ve changed.”

From a few sparse paragraphs of flat prose, you now have an image of me. With minimal information, largely about my tastes, you will have slotted me somewhere in reference to you: somebody to get closer to, somebody to get away from. You will likely also have an image of the sort of people I prefer to be around. And you’ll probably be right.

You might be too polite to say it out loud, but behind this positioning is a set of judgments about me, issued almost involuntarily: cliché urban cosmopolitan; wannabe intellectual; self-important navel-gazer. You might also have thought some nice things. Either way, your perception of me is far from neutral: it expresses your tastes. You are judging me, but in doing so you are also judging yourself—as the sort of person who would think such things about somebody like me. Depending on how you do that, you move yourself closer to or further from me.

Like so many iron filings falling into place around an electromagnet, we align ourselves with those who like what and who we like and distance ourselves from those who do not. The technical term for this concept is homophily, “love of the same.” Homophily—and its less-mentioned opposite, heterophobia, dislike of the different—underlie the theory of social order that has come to govern much of our lives.

[LOL, OR: THE WORLD CLOSES IN ON ITSELF]

This theory is expressed in the principle of the like button: you like this, I like this, we like each other; we are friends. You don’t like this, I do like this, we don’t like each other; we are not friends. You liked her, but she liked what he said; I don’t like him; I don’t like you. I need to get away from you, you need to get away from me. Call it the “Logic of the Like.”

There is an immense power to this way of thinking. For social media companies, the Logic of the Like distills the seemingly ungraspable complexity of social life into a few simple processes, and allows an entire social edifice to be built up by iterating them. As we rate and approve, upvote and downvote, we sort ourselves into clusters. Recommendation systems in turn feed us content similar to what is popular with “people like me,” creating incentives for new products to approximate, with slight variations, what is already popular.

For social researchers, the creation of technologies of communication and interaction governed by this logic presents an irresistible opportunity. In ways that seemed impossible just decades ago, we can now map the invisible threads of liking and disliking that hold the world together and organize it into clumps and camps. The books you like on Amazon—from Hemingway to Hillary—tell us not just what you like but who you stand with and against, and modern computational techniques allow us to compress millions of everyday judgments into a single graph that plots each of us into our assigned place.

The Logic of the Like has been so useful to social media companies and social researchers because it is a form of social life that taps into and intensifies powerful human passions. And indeed, to all of us, the Logic of the Like offers a seductively thrilling form of democratic world-building. To enact it is to participate in creating an order that stands on nothing more than ourselves, our own tastes and interests. No central authority determines what or who we should like, or not like. The kind of power traditionally enjoyed only by media executives or emperors, of raising or lowering the stature of some private person by placing them before the eyes of the public, now belongs to us all.

Meanwhile, seemingly insignificant expressions of taste—do you like or dislike these beans or that cookbook author—become laden with the weight of the world. Every like is itself and more: the beans and the social meaning of the beans are contained in the same act. You fight your battles, but the contest is really about the shape and tilt of the battlefield itself. This is a never-ending story: if you drop out, so too does your taste profile, and the interaction order becomes that much more alien to you than it was before. Each like demands another like; each like is more than this like. To present an easily accessible pathway to being more and more-than yourself—in a word, to transcendence—is perhaps the root charisma of the Logic of the Like.

And yet, as new communication technologies expand and come to structure more and more of our interactions, it is hard to avoid feeling there is something lost in living by the Logic of the Like. We reach for terms like “homogeneous,” “simple” or “flat” in order to express some truth about life in a world reduced to vectors of attraction and revulsion. Homogeneous, because of the tendency to steer ourselves toward others who already view the world as we do. Simple, in that complex emotional life is compressed into a single scale with only two sides: like and not like. Flat, because it seems to reduce the depth and texture of life.

But these terms fail to capture what is perhaps the most potent feature of the Logic of the Like, which is its seeming inescapability. It is similar to Thomas Hobbes’s theory of religion. We create a God whose needs and desires in turn come to control us. And the Logic of the Like is a jealous God. It admits nothing outside of itself, even its own negation. For example, suppose you decided to reject homogeny and seek out difference, contingency and surprise. A noble pursuit, perhaps, but easily assimilable: “I think we should expose ourselves to difference” is exactly what someone like you would say. It is a self-organizing system but also a self-enclosing one.

Or suppose you rejected simplicity and instead of only using the like button you used the sad faces and angry faces and surprised faces (“reactions”). Or even better, imagine if I were a better writer and could express in rich detail the full range of emotions I felt every step of the way as I stood there between Lake Michigan and the Loop, poised on a knife’s edge, hovering between nature and culture. A more complex picture, to be sure, but not a problem for the Logic of the Like. We count up the evaluative words I use, assign each of them a value as a positive or negative sentiment, and score my experience according to their sum total: now he likes cities more than nature. More complicated techniques can sidestep the requirement to reduce my statements to a single scale, and classify me according to how similar the combination of words I use is to other people’s descriptions of natural and artificial objects. The end result is the same: I’ll be positioned in a mass of data points alongside others who respond to the world as I do.

Or suppose you decide to leave the flatlands of the Logic of the Like and seek out the depths of experience in great literary works. For instance, instead of, say, spending an afternoon thumbs-upping TikTok videos, you sit down to read Flaubert’s Sentimental Education and find yourself carried away. Surely there is a realm of aesthetic autonomy here? No, the door remains closed. According to the Logic of the Like, the desire for aesthetic purity is itself a particular type of interest: an interest in appearing disinterested. And just as surely will you tend to find yourself drawn to people who share that interest, and repulsed by those who do not. There is no exit.

[THEORIST OF LOGIC]

If there is one theorist who, as much as any other, articulated the Logic of the Like, it is the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. In fact, Bourdieu advanced a reading of Sentimental Education that sought in it both an expression of the latent class structure of nineteenth-century Parisian society revealed by the tastes of its characters and of the strategies by which literary publics use claims to aesthetic autonomy to advance their own social positions. While this did not endear him to traditional literary critics and lovers of literature, it does point toward his value as a guide into the inner logic of the Logic of the Like.

Bourdieu was born in 1930 in a remote village in southwestern France and grew up in a family of modest means. A person of remarkable talent, creativity and drive, he rose through the pyramid of French academia, culminating with his election to the Collège de France in the 1980s. His humble origins as an outsider who scaled the heights of the social and career ladder provided the background, in his own telling, for his ruthless depiction of Parisian high society as illusory refinement masking systems of domination and control.

Though he was trained in philosophy, Bourdieu’s interests turned toward anthropology and sociology early in his career. At the time, the ascendant approach was Claude Lévi-Strauss’s structuralism, which promised empirical and scientific answers to traditional philosophical questions about the nature of meaning, culture and value. Bourdieu was drawn to the structuralist attack on purely theoretical reflection, and received a push in that same direction while stationed in Algeria in the late 1950s as part of his military service. There he conducted fieldwork to which he would return throughout his career. But this work also led to key theoretical insights that eventually caused him to reject Lévi-Straussian structuralism.

The central insight that led Bourdieu away from structuralism concerns the concept of social rules. Traditional structuralist accounts offer rich description of the systems of rituals and symbols by which a person attains honor, for example, within a given culture. Bourdieu argued that such accounts yield little insight into how people act. This is because people routinely play seemingly established conventions off of one another, or adhere to such rules for the purpose of hiding their own concrete interests. There are the rules, and then there are the rules. Indeed, Bourdieu observed that elaborate rituals for demonstrating a person is not greedy and cannot be bought off have the effect of advancing and profiting that person, while reproducing their social position. This need not occur consciously—in fact, it cannot, according to Bourdieu—but instead arises through ingrained patterns of perception and behavior, the “habitus” individuals imbibe through their early childhood upbringing.

This same thought informed Bourdieu’s critique of Max Weber’s sociology of religion. Weber had famously argued that “religious rejections of the world” had transformative social potentials. While Weber recognized that religious movements emerged at particular social and historical moments, he took seriously the substantive values of religious teachings. “Sell all you have and give to the poor,” “the mind is freed from its accumulations, it has reached the cessation of desire”—these and similar prophetic renunciations are for Weber not reducible to covers by which social groups advance their standing. In rejecting “the way of the world” as it is, they also rejected the us-versus-them of existing kinship and tribal affiliations and made new forms of community and solidarity possible. Bourdieu, denying what he viewed as Weber’s sentimental idealism, instead reinterpreted the words and deeds of prophets as so many moves in the game within their local relationships and power struggles—their religious “field”—which expressed habituated “strategies” to accumulate followers and attack rivals.

Bourdieu began by directing his critical social theory toward the distant past and at “exotic” non-European peoples, but he did not end there. Bourdieu brought his weapons home, turning them on French society and culture with a vengeance. This culminated in his most famous work, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Published in 1979 and based largely on a national survey of cultural tastes, as well as snippets from newspapers and personal observations of fashionable society, Distinction argued that what seem like our most personal and private sensibilities are produced by and in turn reproduce our class position. Our opinions about what food tastes good or bad, what music to play at a social gathering, what pictures to hang on our walls—those judgments position us vis-à-vis one another, and those who accumulate more “cultural capital” not only tend to dominate the game, they define what it means to play it well. This is “the real cultural game” played out by the “privileged in privileged societies, who can afford to conceal the real differences, namely those of domination, beneath contrasting manners.”

On the basis of this analysis, Bourdieu developed a more subtle class theory than his Marxist predecessors. Instead of placing all occupations on a single scale from poor to rich, Bourdieu could distinguish between professors and plumbers. Even if the two might earn similar amounts of “financial capital,” the former possessed substantially greater “cultural capital,” buying them access to social domains off limits to the latter.

While this schema may mark a real scientific advance, Bourdieu did not aspire merely to academic understanding. His is a contemporary variant of the perennially seductive impulse to debunk. In this tradition, you identify those aspects of the world that have some kind of aura around them, and you rip the halo off. Voltaire did this for politics: behind the purple robes are mere mortals asserting their power. Feuerbach did this for religion, which he said was nothing but the projection of human needs. Marx did this for the economy: the mystique of free markets and private property is a mask by which some dominate others. Bourdieu, too, is a debunker. This is why he started with poets, novelists and aesthetes—those who were still wearing their halos. By transforming their activities into forms of positioning, he brought them down to earth, exposed them as inescapably determined by “the ways of the world,” and demystified their claims to be otherwise.

[THE NORMALIZATION OF A SCANDAL]

Bourdieu’s analysis was initially seen as scandalous, and it has faced harsh criticism from sociological theorists. The most persistent charge has been that his theory is highly deterministic and reductive, leaving almost no room for growth or transformation, while assuming that any difference between groups—including in food or music preferences—is ipso facto motivated by a desire to maintain power differentials. It is one thing to show, for example, a correlation between education and liking Sufjan Stevens; it is another to demonstrate that liking Sufjan Stevens has the effect of maintaining social hierarchies, and yet another to prove that those who like Sufjan Stevens do so in order to maintain those hierarchies. One of Bourdieu’s most strident French critics referred to collapsing the distinctions along this chain of reasoning as a form of “sociological terrorism.”

To the extent that Bourdieu did attempt to respond to his critics, he was never able to develop a compelling theory of social change beyond new entrants seeking to displace incumbents or to offer insights into the nature of social or artistic creativity. To do so would have required backtracking on his critique of Weber and admitting there were types of action that were not best described as mainly instrumental or strategic.

There is no shame in advancing a novel but incomplete social theory, and such critical debates are the normal stuff of intellectual discourse. What is striking, however, is that, whatever its weaknesses, Bourdieu’s highly contestable and partial theory has over time come to describe aspects of our social life with frightening accuracy. This is not because he refined the theory in any notable way; rather, the parts of the social world that best embody it have grown to increasingly structure how we interact.

The desire for recognition, and the wish to win the approval of highly regarded personages, is far from new. But social media and online rating and streaming-recommendation systems have hypercharged these desires and removed obstacles to giving them free rein. They did so in part by adapting and commercializing concepts and techniques forged by the pioneers of modern market and social research. Like a virus jumping from the lab into an environment in which it thrives and spreads, the Logic of the Like in this way escaped the confines of academic research reports, found a setting to which it was highly suited, and in turn came to dominate that environment and those of us who occupy it.

[PRACTICE OF LOGIC]

Facebook added the like button to its platform in 2009, but the concept of tracking emotional responses to flows of information is older. Together with other innovations such as the “focused group-interview” and the concept of homophily itself, mid-century Columbia University sociologists Paul Lazarsfeld and Robert Merton devised like and dislike buttons as a novel data-collection technique. Lazarsfeld and Merton showed videos to regular people (such as housewives being encouraged to cook with less meat) and gave them buttons to record their emotional responses. They followed these with focused interviews to register what was driving their choices, in their own terms.

Lazarsfeld, Merton and their colleagues identified fundamental societal shifts that would only later be codified by Daniel Bell as “the coming of post-industrial society” and a “revolution in sensibility.” Their like buttons were part of a package of innovations designed to tap into the rapidly changing social world the Columbia sociologists saw emerging around them. These changes included, among others, the rise of national media, credit cards and cars, which fused with cultural changes—most notably the expansion of bohemian and New Age philosophies—to support a broader ethos of personal self-expression and authenticity.

Even so, their like buttons remained rooted in an older, industrial, one-way relationship between company and consumer, researcher and subject. Merton and Lazarsfeld brought people into a room, showed them some videos, gave them buttons to push, asked them questions—and then everybody went home.

To understand how the like button has migrated in the 21st century from the lab to life, we can look across the Atlantic, where Bourdieu himself was working with other French researchers charting similar trends and also developing methods designed to reveal the operations of the Logic of the Like in everyday life. A notable pioneer of what would become modern data analytics was Jean-Paul Benzécri, one of Bourdieu’s lifelong friends and classmates at the École Normale Supérieure. Bourdieu himself remarked: “Those who know [Benzécri’s] principles … will grasp the affinity between this method of mathematical analysis” and Bourdieu’s own theory of social order.

These methods enabled the analyst to represent social life precisely as Bourdieu had theorized it, as a space of positions and a game of positioning. Benzécri promoted a family of approaches that would later be called “Geometric Data Analysis” (or GDA) or “factorial analysis.” The basic impulse of geometric data analysis is to devise techniques for locating and visualizing individual cases on a diagram, where their positions are determined by the similarity and difference of their responses when compared to one another and the most distinctive characteristics within a population become the most visible. They afford a view of the social world in terms of groups held together by the few items that they like the most and the least, clumping people at the extremes of their taste profiles. The clumped clouds of points of geometric data analysis were the physical manifestation of a distinctive view of the social world crystallized in the Logic of the Like.

Though techniques of geometric data analysis were widely known, their use outside of France and parts of Europe was relatively uncommon in Anglophone social sciences until the late 1990s and early 2000s. Computer scientists and market researchers began to adapt and update them in combination with other emerging techniques utilizing similar principles around the same time in developing recommendation and targeted advertising systems, attracted by their ability to reduce the complexity of large high-dimensional data flows generated by internet activity and to feed users the types of items liked by people similar to themselves. Social media firms, for their part, used iterations of these techniques to make predictions about what content would most reliably and predictably attract the most attention from users. In the process, they discovered that, as computer scientist and AI researcher Stuart Russell puts it, the solution is not “to present items that the user likes to click on.” Rather, “the solution is to change the user’s preferences so that they become more predictable.” The most predictable users, it turns out, are those with the most extreme or distinctive views. In iteratively feeding users the most extreme items that most distinguish them even from highly similar others, the algorithms learn that the best way to maximize their own reward—more likes—is to heighten the tendency in their environment—their users’ minds—toward extreme positions. Social media companies more accurately predict likes by installing the Logic of the Like in our minds as our primary conception of social order.

Theory and practice converged, yet in doing so the theory moved from the background to the foreground. For Bourdieu himself, uncovering the Logic of the Like was to penetrate beneath the surface. Indeed, in using Benzécri’s factorial analysis methods to uncover clusters of individuals held together by the latent principles of distinction, Bourdieu believed he had found the modern analogs to the clans and tribes of his structuralist forebears from Durkheim and Mauss to Lévi-Strauss. Today, though, no theory is necessary to understand social life in this way: in the age of social media, it comes naturally to us.

[LIFE ON EARTH]

The attraction of the Bourdieusian style of analysis comes in large part from bringing the angels down to earth: armed with empirical data and analysis, it appears to be insulated against idealistic delusions about human behavior. But what does it mean to live on the earth?

Bourdieu’s earth is the dark inversion of the Kantian heaven it imagines. If the angels are disinterested and disembodied creatures—somehow above and beyond the pursuit of power and position—then life on earth is the opposite. Bourdieu resisted drawing any direct normative lessons from his social theory. Still, insofar as it seems to imply one, it is that if we are to face up to social reality and be honest with ourselves about its real stakes, we may as well learn to play “the real cultural game” well—that is, ruthlessly. Of course this implies too that Bourdieu’s books are themselves a part of that game, only played, as he put it, in a more “self-reflexive” way. Ultimately, his sociology reaffirms the inescapability of the Logic of the Like. It is a form of negation that leaves you nowhere else to go and nothing else to do. Power and position are what is left when there is nothing else to live for.

The escape from the infinite loop of the Logic of the Like, then, must begin with an appreciation for the richness of human experience. Bourdieu often described himself as a theorist of practice, a sort of pragmatist who believed that practical exigencies trump high-minded ideals. If we turn to other self-described theorists of practice, however, we find a contrasting assessment of what practical life on earth entails. John Dewey stands as a powerful case in point.

Bourdieu and Dewey seem to share much in common and are often discussed together as incisive critics of disembodied reasoning. Yet their pragmatisms could not be more different, most obviously in their intellectual style and affect but also in their substance. If Bourdieu’s pragmatism leads to a hard-edged cynicism, Dewey’s resulted in a more open-ended faith in the potential of democratic progress.

When Bourdieu proposed his own version of democratizing culture, he meant making the cultural styles of elites available to the masses through reforming their habits and, for example, providing more interpretative support for their encounters with high culture (placards in art museums and the like). In effect, democratization for Bourdieu meant expanding the number of players in the status games of the privileged. For Dewey, on the other hand, democratizing the arts was important because it would enrich the lives of numerous people and build our capacity to communicate across social divisions. This experiential focus was crucial for his vision of a pluralistic democracy—one where all those affected by a problem have some say in how to respond appropriately.

Dewey acknowledged that we begin from categories, classifications and positions, but his entire philosophy was set against the notion that those classifications could be the end of social and political life. In his view, rather, there was no end, only temporary “ends-in-view,” and life—real practical life—was an endless process of testing them. Art, in his view, is “more moral than moralities” because it not only aims to enforce conventional goods and ideals but discovers and realizes new ones.

Because he saw individuals’ fulfillment as being intimately tied to their social environment, Dewey’s pragmatism was geared toward creating practical conditions for realizing the proposition that “the powers of a man are not fixed, but capable of modification and redirection.” Accordingly, he was a deep critic of any structure of thought or interaction that pushed us in the opposite direction—toward ways of interacting that make it more difficult to undergo “the growth of character and conduct” that comes from opening oneself up to new possibilities that arise in the course of one’s activities. The competing visions of life represented by Dewey and Bourdieu could be described as the growth and enrichment of experience versus the logic of interested practice. How do we evaluate them? The pragmatist answer is that we put them to the practical test: try them, entertain their implications and see what happens. We have seen the practical maxims of the Logic of the Like and where they lead: to Spinoza’s “they provoke mutual dislike.” Rather than sketch out a Deweyan alternative in the abstract, therefore, I would like to suggest that a bit of pragmatist practical wisdom may be found in a homely maxim of everyday life: don’t judge a book by its cover.

[COVER STORY]

I don’t know the history of the phrase, but I’d like to imagine that it was a hard-won outcome of collectively learning to deal with the massive proliferation of books as distribution technology improved, and their capacity to spread information, good and bad. I imagine that for a time simply seeing something in print, on pages bound between two covers, could give the allure of authority, and that this would be a recipe for disruption and division. “Don’t judge a book by its cover” is a cognitive truism but a practical challenge, the truth of which comes from living it, not knowing it.

Today we have metadata and data in place of covers and books. Data is the real thing, the information we care about. Metadata is additional information that accompanies the important stuff. For example, in a conversation the data are the things you say, or more properly the meaning of your words as they pertain to the experiences they make evident. Metadata could include aspects of your background, such as your age or religion, or also your workplace, or the types of caffeinated beverages, TV shows and vegetables you like. Metadata is like the cover of a book. If you have lots of covers of lots of books, you can probably get reasonably good at predicting from the cover what is in the book. Similarly, with enough metadata about you, it is possible I might get pretty good at predicting what you will say or do based solely on the metadata.

There are many useful applications of this ability to make predictions based on metadata. Does this give the lie to the saying that you should never judge a book by its cover? It does if it means that the meaning of a cover is exhausted by its function as a signpost or indicator of what you will find inside the book. In that case, with enough metadata, and enough data, enough books and enough covers, you might conceivably never need to read a book again. Similarly, you’d never need to talk to anybody again. You’d know what they would say already. In the Logic of the Like, the distinction between metadata and data collapses.

But that does not capture what it means for a book to have a cover. The cover is also a ritual boundary, like changing into a uniform before starting a karate class or saying a prayer before entering a sacred space. There is an inside and an outside. The cover indicates that you are about to start something that will have its own experiential process of buildup and completion, distinct from the world outside. It is a warped space in experience: there is depth to it. It needs to be penetrated, and some kind of essential secret needs to be revealed. To understand it is to go through it. This means there is necessarily something held back that emerges in the process of engagement as it builds towards its own internal climax—a world with an inner and an outer, a surface and a depth, a front and a back, a manifest and a latent, a seen and an unseen. In Dewey’s terms, this is the movement from “experience” to “an experience.”

If we imagine that metadata is all we need, we are imagining a world in which there are only covers and no books, experience but no experiences. There might be pages, but every page is just another cover. It would be covers all the way down. You can read a book this way, extremely closely, but it will never escape the Logic of the Like. To do that, you need a book you can’t judge by its cover.

[JUDGE NOT]

In the Logic of the Like, clicking the like button amounts to what Dewey referred to as juridical “verdicts.” A verdict seeks to lay down the final word about what the meaning of an event consists in, on the basis of an authoritative touchstone. They are necessarily bound up with the exercise of control. Hence the focus of Bourdieu and his followers on gatekeepers who attempt to protect the power to classify. The wisdom of “don’t judge a book by its cover,” by contrast, comes closer to Dewey’s notion of judgment. Rather than being the most fundamental dimension of human relation, judgments (likings and not-likings) for Dewey are just one part—albeit an important one—of his broader theory of experience and practice. A well-placed “I like it” or “hmm, not sure about that” can help to move a conversation forward, or in a different context break it apart before it reaches its full potential. In either case, Dewey’s focus is not about how the judgment reflects back on the class position of the judger, but rather about the role of making or reserving judgments in serving or stymieing the buildup of an experience.

Dewey’s way of thinking has implications that extend beyond interpersonal dialogue. The sweeping social significance of the capacity to periodically suspend judgment, to even momentarily exit the Logic of the Like, is evident in sociologist Christopher Winship’s account of the emergence of Boston’s TenPoint Coalition in the 1990s.11. Winship’s study appears as a chapter titled “Accidental Discovery and the Pragmatist Theory of Action: The Emergence of a Boston Police and Black Ministers Partnership” in The New Pragmatist Sociology: Inquiry, Agency, and Democracy (forthcoming in fall 2021 from Columbia University Press). The TenPoint Coalition is a group of African American ministers and laypersons that partners with police with the goal of reducing violence. It played a key role in the “Boston Miracle,” during which violent crime in the city was dramatically reduced. The partnership, however, was highly unlikely given the history of deep tensions between police and local Black communities in Boston. Indeed, prior to its inception, through a series of interlocking and escalating events, relations between community members and police had hardened to the point that communication had stalled, mistrust was rampant and they were figuratively “at each other’s throats.”

Two well-established, conflicting interpretations of the situation had emerged: one blamed moral decay, the other blamed discrimination and racial oppression. Police and ministers largely aligned on one side or the other. Each simultaneously held clear understandings of their own roles in the neighborhoods: police as “effective fighters of crime” and ministers as “guardians of the church” offering a “sanctuary from the ‘war.’” As events unfolded, both interpretations became unstable. Various scandals, often around hyper-aggressive tactics, undermined the public legitimacy of the police and their generally reactive approach to violence. A stabbing and shoot-out among gang members during a funeral service at a Baptist church for a youth murdered in a drive-by shooting challenged the moral authority of the ministers and the sanctity of their churches. “The message was clear—if the church was not going to deal with the problems of the streets, those problems would enter the church.” The authority of both police and ministers was in doubt, but neither had a clear sense of what to do. They occupied the same space, held similar goals of “dealing with the problem of youth violence,” but the commitment was parallel, not shared in a joint project.

Faced with this situation, the ministers tried something remarkable: they began to wander through their neighborhoods, in what Winship calls “purposeless engagement.” In this way—by temporarily suspending judgment while continuing to act—the ministers allowed a situation that had congealed into clearly delineated, interconnected but noncommunicating camps to loosen up and admit new possibilities. The ministers literally did not know what they were trying to accomplish. “All they knew was that they were called by God to be present.” They would bump into gang members and police and strike up conversations, but without a clear agenda or plan, even a plan to come to the table and negotiate: “There was no table in the story.”