Here is where I am now: I am not interested in having sex with anybody unless it is the last person I ever have sex with. That is the ideal at least. I know there could be exceptions, when I do things I don’t truly want to do. I know there could be broken hearts—because you can’t always know you want to stay with someone forever before you have sex with them, can you? It wasn’t always this way. I was no enemy of casual sex; I did it when called to. But there was always some unease with it, some misgiving that I couldn’t define, or, perhaps, wasn’t even aware of. My life of late has been in no small part the story of coming to terms with my unease.

Like all stories, or at least the good ones, this is a story about another person. It is a she, and she is a joy to hold because we fit just right together. She is also uncommonly, eternally stubborn. She would probably call me stubborn too; I accept that. For over a year, despite not spending all that much time together, and despite remaining, on some deep level, strangers, we were each of us a thorn in the other’s side. And for over a year we were each of us also, each for the other, a figure of great fascination, a preoccupation and a pleasure. It is difficult to say whether the fascination was caused by the thorniness, or the other way around. It is easy to say what we argued about: we argued about sex. Which, as it turns out, is a much bigger argument than we ever could have guessed.

●

There was a prehistory for us. I have a close friend named Dan, and Dan’s girlfriend is Maria, and a close friend of Maria is Penelope. Penelope is her. Two years before she and I met, Dan told me on the phone: “I’ve got a girl for you.” He indicated how I could find a photograph, and I found one; if there was some kind of gleam in my eye when I looked, I don’t remember, even if I do remember being vaguely struck. Dan was quick with a warning: Penelope and I would probably disagree a lot. But underneath the surface—so he sensed, my friend Dan with his knack for character—there was “something there.” A something to do with our respective idealistic natures. Or maybe some other something. Just something. So I counted myself interested in meeting this Penelope, this one with her eyes turned down in her photograph and her undefined communion with me. Then she was filed away and I went back to the rest of my life.

When we met, two years later, it was cold. Dan and Maria had invited me to her family’s house in the countryside just before Christmas, to be joined by her sister and brother-in-law. My friend Dan—devious, to go along with his knack for character—neglected to tell me that a certain young lady was invited until an hour before I got in my car. The fix was in. My trip became a little more enjoyable, the scenery along the road looked just a little better.

She was late—always late, as I would soon discover—having missed the train up from the city with the rest: I was greeted by Dan and Maria, and Maria’s sister Lauren, oddly slender despite being eight months pregnant, and her husband Geoff, obsessed at the moment with auto repair and the biology of pregnancy. When Penelope arrived and walked into the kitchen I happened to be holding a four-pound package of ground beef in my left hand, thinking the stupidest of thoughts when I saw her, that thankfully I wouldn’t have to switch the ground beef from one hand to the other since my right hand was already free for shaking hers. After fifteen minutes or so of general hubbub, the kitchen cleared out implausibly quickly, as if everyone else knew something we didn’t, and then there we were, claiming to be talking, but really just beholding each other. I will admit that I was looking at her face much more than could possibly be considered normal, in part because I could tell she was attracted to me and I was enjoying it, but also because I just couldn’t stop looking at her eyes—her eyes not turned down like in the picture, but sad all the same, even through the frames of the glasses. I was tired, and when I am tired my left eyelid droops, and I found myself wondering if she could see it, or if she liked it. Words passed between us, too, although I don’t remember many of them. I do remember that one of the first things she said to me was “so I heard you’re a philosopher?” and I felt a trace of annoyance, because “philosopher” is a bad word as far as I’m concerned, but I didn’t say anything. But I did think, and I thought it unmistakably, that I was being provoked; just a trace, but it was there.

The tension grew over the next few days. It was borne up by bodily clues, like a small hesitation when passing in a hallway; or by the intonations of our friends’ sentences, which, like their disappearances from kitchens, revealed a lot. The otherwise equanimous Maria was just a little too excited to find out that her friend and I had brought the exact same toothbrush. Meanwhile I lost no time in picking up on Penelope’s initial provocation and amplifying it. I paid the price. During a long conversation following another room-clearing, I was told that a movie I had just come to adore, I Origins, was “sentimental,” and that I was sentimental for adoring it. Why, I wondered: Was it because the dreamy romantic wins and the hardheaded scientist loses, and it was all fated from the beginning? Do you not like movies where the romantic wins, Penelope? “I have nothing against romance. That’s just not my idea of romance.”

The kiss finally happened on the last night there, the Eve of Christmas Eve, already one more night than I was supposed to stay. The tension had become almost unbearably obvious, which is to say, it was just right, or for me at least. I thrived under the conditions; Penelope apparently did not. When it was clear what was about to happen, the gaps from her side of the dialogue got longer and longer, such a reversal for such an inveterate talker. And then, the very moment before, seconds before—I believe I have never seen a woman so nervous. I didn’t think too much of it, not that I was doing much thinking, but I remember that after we were finally wrapped up in each other and allowed to touch each other, I was overwhelmed with affection, and it was precisely because of the anxiety she had just been suffering. That this thorny, difficult creature could be so vulnerable, and so out of character. It made me want to protect her.

After a couple of hours of our lying about on the living room couch I went outside to smoke a cigarette. (Penelope: “Do you really need to smoke? What would happen if you didn’t?”) Snow had started to fall. It was late, quite late, and clearly no one else in the house was stirring, although I found myself asking in my nicotine haze if Lauren’s baby ever kicked inside her belly at night, and if she could sleep through it. (Being so slender, wouldn’t she feel the kicks more?) When I went back inside I planned to say goodnight and then retire to my room; I was driving the next day and wanted to be reasonably alert, and Penelope was getting sleepy besides. But it was destined never to be so simple.

Allow me to speak briefly, for it is not seemly to speak at length about such matters. Let’s just say that a certain event that could have taken place didn’t take place; and it was because of me that it didn’t.

I wanted to; of course I wanted to. I just didn’t truly want to. I tried my best to explain, which consisted mostly in lamely repeating to her, “it’s a compliment, it’s a compliment.” Because the room was so dark, I couldn’t see her eyes, but I had the distinct suspicion that she was looking at me like I was an alien. “It doesn’t feel like a compliment, it feels like a judgment. Why can’t you drop your meaningless rules and do what your body desires?” The rules weren’t meaningless; why was she accusing me of doing something meaningless? “Okay then, pointless.” Later on, deeper into the standoff, I got a sentence from her that felt particularly honest, even more honest than all the other sentences, maybe because it sounded like it came from well within her: “I want to get to know you.” But what could I say, other than that I was touched? I wanted to get to know her too—just… beforehand. I gave up. We both gave up, and by the end of a long hour, our teasing flirtation, which had always been pleasant to some degree, entirely stopped being pleasant and just became unadorned anger. I remember thinking to myself, as the conversation lost all pretense of benevolence, “Wait, is this really happening?” It was, with a person I had known for three days, it really was. And it would not be the last time; and I knew even then that the anger was binding us together.

The following morning: wrapped up in a bath towel, beautiful shoulders and a wounded look. A dash to get out of the house. Standing in the snow next to my obnoxiously loud car waiting for it to warm up. A wave of the arm from her as they drove away. Somewhere back in there another attempt to explain, which failed. And a very long hug.

●

We would see each other again soon. From my genial home in the provinces I made the assumption, rightly as things turned out, that it was just a matter of finding a plausible excuse to get back to the city, an excuse whose plausibility she would consent to, all in the proper, unspoken way. In the interim I didn’t speak much about her to others, not even to Dan—best not to speak of her. I thought a lot about her. I thought also about the last night and the anger.

I had to admit to myself that on the night in question I was by no means in possession of a comprehensive theory of sex and relationships; I may have felt strongly about how I acted, but I acted from the gut. What I was starting to work out back home about my own history—piece by piece, and with dawning surprise that I had never made it explicit to myself before—was that I had always seen physical encounters as a choice, and assumed that the other person did too. If there was potential for something serious, even if I and the other didn’t speak of it, then we went slow; if there was not potential for something serious, then that went its own way, without stopping, and that was fine too. I pictured a fork in the road: depending on how we gauged the situation, we either took the long way round or the shortcut. Communication about the matter, meanwhile, was conducted not with words, but with all the other nonverbal means—which are not completely immune to confusion, surely, but usually accurate enough.

The next step I took may have been an overcompensation—a moment of scales-falling-from-the-eyes in which I doubted whether I had communicated with anyone, ever, all along—but it was not overcompensating to acknowledge that, through some combination of the shifting of customs and the sheer accident of my own history, I had landed in my first encounter with someone who definitely, assuredly did not agree with me. I knew that my way of doing things was not the usual way. I also knew that hers was. But, and this will stun no one who knows their own soul, I thought that she was wrong and that she should know better. I thought the same thing too, unabashedly, about the rest of the world.

It was all so intuitively clear that I did not even feel the need of a defense. I made a token effort and generated one idea: sleeping with someone too soon is like sharing secrets too soon in a budding friendship. You’re tempted to do it, and it feels good in the moment, but it is damaging in the long run. I thought I didn’t need much more than a comparison like this one to defend myself if Penelope and I started arguing again. Not that I was planning on arguing when I saw her; our emailing had been civil, and I assumed we would tactfully avoid the topic, in order to just go about the happy business of getting attached to each other. In retrospect, my miscalculation seems fairly hilarious.

●

About a month later, at the end of January, Maria and Dan and I sat in a bar in the city, waiting for Penelope. She was late again, and so extremely late that the three of us, who would have been happy to talk for hours back at their apartment, were running out of things to say. Thankfully Penelope was charming upon her arrival, not because her lateness made me want her more, but because it revealed her to be such a mess. And I of course was nervous, as any human should be, in the mere presence of somebody I was completely and totally attracted to.

We remained polite for about fifteen minutes. The arguing started when she revealed that she had recently rewatched I Origins; she still disliked the movie and made no effort to hide her condescension, informing me that I was too invested in neat coincidences and happy endings. This, naturally, was all the invitation I needed to be as obnoxious as possible. Didn’t she understand that you can never really be set free from the past? Perhaps her judgment of the film was not a pure one, given her conceptual difficulties, which obviously resulted from her shortcomings as a person. I may not have said that last thing explicitly, but she felt it, and anyhow why was I so angry to begin with? Then, as if we were not already in enough trouble, by some accident in the flow of dialogue things got even worse, reaching a climax so nonsensical it will probably always evade my comprehension. I cannot remember how we got there; I remember only that I enraged Penelope by declaring that one of the two actresses in the movie—Àstrid Bergès-Frisbey she is called—was not beautiful. Maria by this point had chosen a side, even without having seen the movie, and stepped in on behalf of a fuming Penelope: How could you possibly claim that an obviously beautiful actress is not beautiful? My answer: “How could she be beautiful? I’ve never met her.” That didn’t help. It also didn’t help that none of us were sure how to pronounce the name Àstrid Bergès-Frisbey, which we were nevertheless forced into saying over and over.

Dan made an effort to mediate; it was of no avail and he went quiet. Maria went quiet. Penelope and I had dropped the pretext of the film and had started using each other’s comments as the basis for instant, judgmental psychoanalyzing. The argument became about the argument. Then, inevitably, the argument became about the argument about the argument—and then finally the escalation imploded under its own weight, until there were no words at all, just staring. It was an achievement, in a way. We had attained a sweet spot of social discomfort: not so disruptive that the frame for the conversation itself fell apart and the night ended, but disruptive enough to prevent anyone at the table from speaking. Dan and Maria sat there, squirming and astonished, as Penelope and I did nothing other than glare into each other’s eyes for several minutes. Maria would later tell me this was the most unpleasant social experience of her entire life.

When Dan and Maria walked out of their bedroom the following morning to find me and Penelope snuggling on the couch I was crashing on for the weekend, they were surprised. But they were clearly pleased, which is more than one can say for the poor bartender of the night previous, who had nevertheless been kind enough to allow two patrons to yell at each other for twenty minutes before finally kissing and leaving so he could clean up. Right before the kissing I told Penelope that she—and not the actress—was one of the most beautiful women I had ever seen. That seemed to do the trick. The rest of the long weekend followed the same pattern: antagonism followed by reunion. We fought constantly and made everyone uncomfortable, and then at some point the antagonism would break. I might have suspected us of putting on a show for our audience had the feelings not been so overwhelming—which is not coincidentally something an audience can read too, and read easily. Unlike high school students who desperately want to shock, we weren’t even trying, and so we made the people around us genuinely unsettled.

I don’t think that a colossal energy like ours necessarily heads for disaster. With the proper skill and restraint it can be sculpted into something more manageable, with clearer borders. But we never had a chance, because our disaster was lying in wait for us all along. It surfaced before I even left the city, in a manner that would take my and Penelope’s already strained nerves and simply crush them.

Allow me first to say briefly—for it is not seemly to speak at length about such matters—that on the final night a certain event that could have taken place did in fact take place. It was grand, and it brought a measure of calm. But while we were talking afterward, I asked a question that I suppose she thought I would never ask. I didn’t force the question; the flow of the conversation practically required it; something she said led right into it. “Wait, so have you been with anyone since we last saw each other?” She said she had. And she said quickly, within the same breath: “Haven’t you?” I responded: “Of course not, why would I have done that?” Then less than a minute of silence, and I said: “I think this needs to end.” She asked me if I was joking; I told her I certainly was not. In the dim light of her bedroom I could see her eyes, so I knew for sure that this time she really was looking at me like I was an alien.

The issue was not that I was jealous of someone else; I have at my disposal a large fund of what we might euphemistically call self-confidence. The issue was that I had assumed that not just I, but she also, despite our miscommunication in the countryside, had come to the fork in the road already and had chosen the serious option; I assumed that we had agreed in an unspeaking way not to speak of it; and I assumed that because of the choice, our bodies were now part of our mutual project. I assumed all this, but “assume” is maybe the wrong word, because in that moment it was clearer than ever that my position was not something I possessed, like a thought; I was my position. That was where and who I was.

Before long the where and who of what I was felt like it was in my stomach, and my stomach felt nauseated. The feeling started to spread upwards, tightening my chest, then making my head hurt. I could tell that whatever the nature of the disturbance, it had to find some way out. I started shaking, not as much as in a seizure, but a lot. I hyperventilated, audibly and alarmingly. I had lost control. Using the intermittent self-awareness that remained, I tried to hide myself from Penelope. I also tried to explain myself. I wanted to tell her paragraphs, all about my past, and the things I tried to get free of but couldn’t. But all I could manage with words was a single sentence, and that one sentence over and over. Delivered with a timbre available only to those at their limit, some of it is still in my ear, like the voice of someone else who is not me: “I can’t go back.” “I can’t go back.” Maybe I was being mysterious and theatrical, but I was being honest. I know what I meant. We all have our pain. And it chooses its own moments to announce itself.

We talked until 7 a.m.; never had she been so insistent that we come to a resolution. She tried her best—“How can you know about me already?” “It’s like you want to close off the world too soon”—and I tried my best—“I don’t know about you already, but I know about the potential of you”—but there was no use. We were too far gone. Eventually we drifted off, which put the whole episode to a merciful end.

Looking back on that night from much later, I have been pleasantly surprised at what occupies the greatest place in my memory: not anything from within our endless dialectic, but rather a moment of togetherness. In the height of my unrest, when I had lost control and had turned away from Penelope, she wrapped me up inside her arms, trying to still my body. She moved a hand to my head and directed it—to look at the dim, red-tinted light bulb next to the bed. “Look at the light,” she said. “Just stay focused on the light.” And she kept saying comforting things; and against the odds, that worked. It is difficult to express what this meant to me. I am a certain sort of person, the sort of person who has spent his whole life feeling like there is a wall surrounding him, and only some people can really get through. So when someone does, not only do I want to be around that someone all the time, I am also humbled. Whatever this capacity is, I do not have it. I doubt I could ever be as comforting to Penelope as she was to me. I doubt that she felt what I felt, which was to feel, on some deep level, finally, known.

●

We spent the rest of my time in the city doing what we would be doing for many months to come—with each other, with other people as stand-ins and with ourselves inside our own heads: defending our respective positions. What else could we do? That day at least we made a sloppy job of it, sleep-deprived and overstimulated, but our poor tired bodies clung to their ideals, and we just kept fighting. The final showdown was at a café on my way to the train station, where I hoped that my genuine exasperation would be enough to convince her that dating multiple people at the same time could only lead to lasting commitment in the world of reality television. But the world had shifted underneath my feet, she said; this really is the way things are now so I should get used to it. “Just relax, stop being such a philosopher.” “You can’t be afraid to be in your body sometimes.” Which made no sense to me, because I thought I was in my body all the time, which is why I was so cautious with it. Out on the street, in a night that was quite comfortable, the still unseasonably warm remnant of a day that was unseasonably, freakishly warm, we had our last brief period of amity. “This doesn’t have to end,” she said. “You should know that I’m scared of you,” I said. And we held on to each other, grasping at arms and clothing. And that was it, the last kindness. We started arguing again, our voices started to rise, we pulled our bodies apart from each other, we started to edge in the directions we needed to go—then we told each other to fuck off and walked away.

●

Like anyone, I had experienced disagreements before, even severe ones. That this disagreement too ranked among the severe made it all the more vexing—because I barely knew her. I just couldn’t fathom how a person who was otherwise so reasonable could disagree with me on this of all issues. My position was becoming more and more self-evident to me: when two people meet and they think something serious is happening then they just automatically take it slow, and even if they don’t, they certainly don’t date other people. It would be a different story if polyamory were the goal. But if monogamy is the goal—as it avowedly was for Penelope—and the people involved are excited about each other, how could they really think about anyone else, let alone sleep with anyone else? The very possibility made my stomach hurt. I also thought I had all the evidence on my side, since I had seen so many others go through a process I myself had gone through before: dating in a nonexclusive way, fancy-free—and then, upon being stung, becoming immediately exclusive, without so much as a whisper or even a thought. And to Penelope I could only wish good luck in pretending she hadn’t been stung.

As soon as I got home from the city I did what any healthy human being would do in this situation: I tried to get as many people as I could to agree with me. Strangely enough I succeeded, in that the majority of my friends, at least when pressed a bit, admitted that they shared my proclivities. The most gratifying support of all came from my dear next-door neighbors, in particular the female half of the couple. When she heard that it was Penelope’s policy to keep her options open until further along in the process, she responded simply: “obvious defense mechanism.” All it took was three words. The faster someone agrees with you, the better.

In the long run, though, maybe not fully satisfying—as another close friend of mine brought me to see. My conversation with Francesca marked the end of my initial phase of therapy and the beginning of a new one, because it was she who forced me to acknowledge what I perhaps already knew: that rallying support is all well and good, but one should also try to think through one’s position, to test it from a neutral place outside the debate. Francesca did as a matter of fact agree with me—she had been together with her current partner for a year and a half, and their origin story was both slow-moving and adorable. But my friend Francesca is a ruthless self-examiner, and, more important, she is neither me nor Penelope—and therefore that night she was able to give a nudge in the right direction. “Just take a step back. You’ll have fun thinking about it anyway.” She knew me too well. By the very next day I saw the corollary to Francesca’s message (which she was probably aware of all along): psychologizing Penelope wasn’t fair. Maybe it was true that Penelope’s policy was a defense mechanism. Maybe even probably a defense mechanism. Fear is, after all, the way of the city these days: not putting all your eggs in one basket and so on. Nevertheless, ideas have real power. They are not merely the helpless agents of deep psychological forces. I assume I will go to the grave defending this in my own case; I should accord Penelope the same respect. In sharing her ideas with me she was trying to shape herself, to be herself. She was saying: “This is me, this is who I am.” Best to listen—particularly if I should perchance see her again.

●

Truth be told, I was already theorizing the matter. Even before traveling up to the countryside I had been engaging with a variation on the classic theme of mind and body: I was thinking, namely, about the role of sex, a role I was beginning to find more and more peculiar. (Funny isn’t it, the way that we land in experiences that address whatever we are currently thinking about.) Under the influence of a strain of thinking that grew here and there in the post-Heideggerian twentieth century—in Jean-Paul Sartre, Thomas Nagel and Roger Scruton, to give credit where credit is due—I came to see not only that sex transcends the merely bodily, but that sex, contrary to how we normally think about it, is an activity in which mind and body meet very closely. And the details of this meeting of mind and body are, frankly, somewhat astounding.

Penelope’s “philosopher” quips had rattled me. I knew what the accusation was: the accusation was that I was devaluing the body, through all of my fuss; whereas she was accepting of it, liberated and laid-back. Her stereotype was not entirely unfounded. Since the beginning, most participants in the philosophical tradition have been of the body-hating, or at least body-neglecting, persuasion: poor Thales who fell into a well because he was thinking too hard, the first recorded forefather; and Socrates, the first and highest exemplar—not to mention the martyr who inaugurates the cause. In the Phaedo, the very dialogue of Plato’s in which Socrates goes to his death, Plato puts into Socrates’s mouth a Platonist critique of the body so thoroughgoing that the text can be taken to stand at the head of an entire tradition. (While the situation is admittedly complex—one of the things you learn in the esoteric reaches of academia is that Plato is not really a Platonist, just like Marx is not a Marxist and Descartes is not a Cartesian—it remains true that the Phaedo exists, and that Plato is the author of it.) Having passed through the trial that condemned him, Socrates gathers with a group of his followers in his jail cell on the very day of his execution. Two of them in particular, the “Pythagoreans” Simmias and Cebes, entreat him to defend the proposition that the soul is immortal; they are clearly shaken by the impending death of their hero, and they want to believe. Socrates obliges. Through his characteristic method of cross-examination, both aggressive and roundabout, he spends what are presumably hours presenting arguments to Simmias and Cebes to reassure them. Is the body a lyre or a cloak? Do big things partake in Bigness? Don’t we need to keep the number of souls constant? These are the questions one needs to ask in order to know about eternity. Throughout the entire conversation, however, one thing is never questioned, neither by the interlocutors nor by Socrates himself: that the soul is an entity quite separate from the body—and quite superior to it. Whether the soul is immortal or not, it definitely resents the body for dragging it down. After all, the body, with its compulsive pursuit of wealth, causes conflict and war; and the body, with the mistakes of its senses, makes pure knowing difficult. And the sexual desires of the body? Nothing but a distraction for the philosopher. Those desires are best resisted, aside from the unfortunate necessity of reproduction.

According to the scheme most of us Westerners unreflectively cart around, Christianity—“Platonism for the masses,” as Nietzsche called it—inherited this loathing of the body from Plato and the other Greek founders of the philosophical tradition. A Christian case can be made against the scheme: that the resurrection is a bodily resurrection; that God’s kingdom, as the Lord’s Prayer has it, will come on earth; that the loathing of the body is mere Hellenistic intrusion. Nevertheless, it is hard to forget St. Paul’s admonishments in his letters, or Augustine’s struggles in his Confessions, or the centuries upon centuries of clerical and lay practice, for that matter. And so, at the end of it all, here we are: souls that happen to find themselves in bodies, bodies that want to have sex, just like they want to eat and drink, and we can either accept that or not. But this habitual, commonsense picture is the very picture that I had come to doubt. We are not, in fact, souls that happen to find ourselves in bodies. And sex is not simply a bodily phenomenon, not by a long shot.

Consider a patient being examined in a doctor’s office. Let’s say the patient is a he, and the physician is a she. At one point she is standing behind the patient and places her hand upon his neck—perhaps to palpate the neck, or whatever it is that doctors do. The action, presumably, does not sexually arouse the patient. Now consider the same man, sitting at home. Let’s say he is working at his computer and his wife comes up behind him—it is a game they play—and places her hand upon his neck. The action, this time, does sexually arouse the “patient.” Next, just to make the thought experiment as clean as possible, specify that the duration and location of the touch are exactly the same in both situations; the touch is even applied with the same number of pounds per square inch of pressure. What is the difference, then?

That the mind must play some role in sex—that the mind, too, is a “sexual organ”—would seem clear enough from the comparison of the two scenarios. Yet the tendency to reduce sex to a physical event, a “stimulus” that accomplishes a “release,” rivals in its ever-presence some other crass reductions that the modern, scientistic world appears to specialize in: like the reduction of the fully human psyche to Homo oeconomicus in the social sciences, or indeed the reduction of fully human romance to a game of natural selection in the life sciences. Like those abstractions, the abstraction of the stimulus-release model just won’t stand up to reality. It is not true that the stimulus of the sexual organs in any context—washing dishes, playing baseball, church—will automatically lead to arousal given the proper mechanics. It is not true that sex robots will make human sexual interaction obsolete as soon as perfect verisimilitude is attained. Those thoughts are just instances of a bad intellectual habit, and do not hold up under more concrete reflection about the way life is really lived. The truth can be put succinctly: every sexual relation is a relation between persons. Even if that relation between persons is imaginary, as in masturbation—or if the relation, regrettably, is very much real but very much of the wrong kind.

Think some more about sexual arousal, and think about how deeply interwoven are the body and the mind within it. If you know that another intends to arouse you when they touch you, you find this arousing, and your body will follow suit. This permeation of the body by the mind is itself remarkable enough, although admittedly not unique: getting hit on the foot with a hammer, say, also hurts more if you know someone intended it. But sex is even more remarkable. The memory alone of a sexual interaction can elicit the associated response; whereas no amount of reminiscing about an injury can produce bruises in your foot. Now it is true that reminiscing about an injury can lead to crying, and crying is obviously a bodily response. Yet sex adds another layer here too: no one needs to make contact with your body in order to make you cry; whereas sex is, in the first instance, about touching. (One could imagine two people arousing each other simply by talking and looking—perhaps even, pardon me, to the point where arousal ceases—but there will of necessity be a reference to a past or potential experience of touching.) Whichever way the investigation turns, then, sex shows itself to be, thoroughly and simultaneously, both a phenomenon of the body and a phenomenon of the soul.

There is a way to describe what happens in sex that helps explain this. Depending on one’s philosophical temperament, one might or might not recoil at the formulation, but here it is: In sex, I take my soul and spread it out onto my body for the other. Perhaps, generously, this could be called a metaphor. But is it even just a metaphor? If so, it fits suspiciously well with what really is happening. For the other does want me; and the other does want my body; but it would make no sense if the other wanted either of those separately—my body if it were dead, or me without a body. To assent to the other’s wants, I must take me and put me out onto my body, so that me is accessible in a bodily way. Only then can the marvel of sex be set in motion. That is, only when the soul makes itself flesh and the flesh becomes ensouled.

All of this is a far cry from the Platonic assumption. Not only are the mind and body not separate in sex, they appear to be less separate in sex than any of the other supposedly “bodily” phenomena. In fact, sex may be the place where the body and soul come together; may be the place where we reconcile ourselves to our bodily nature—by putting ourselves out onto our flesh and having another accept us there. In sex, then, we do not become like animals; in sex we transcend our animality. Incidentally, from this perspective, the sexual “revolution” of the twentieth century can be seen as no revolution at all, but just the flip side of the coin shared with Platonism and the history of Christianity. What is proposed in Marcuse’s Eros and Civilization, in second-wave feminist texts like Shulamith Firestone’s Dialectic of Sex, and in the mores of the broader societal movement itself is acceptance of the body and liberation for it. But neither acceptance nor liberation of the body—tied as they may be to central and invaluable goals of the movement—amount to a synthesis of body and soul. The body remains just as detached as ever; one simply embraces it instead of disparages it. Fundamentally, the same theoretical error has been committed. The history of contempt for sex, then, is one big misunderstanding: a dismissal of sex tout court, when what was called for all along was a celebration of sex in its better forms and a condemnation of it in its lesser forms.

●

So here it was, then, the basis for my defense. Radical and sweeping, but not inaccurate I thought—and just what I needed. I fully adopted my new view after my time with Penelope in the city, motivated as one can only be when involved in an all-consuming dispute with a person one has the hots for.

It didn’t take long for me to conclude that I was the winner in the dispute, of course. I was the winner because I saw something that she didn’t. I saw that if the body and soul are always tied together, as the synthesis view would have it, then the process of getting close to someone should be gradual. You can’t simply loan out your body for the purposes of sex while, on a separate track, becoming invested emotionally. Those two processes are not two processes; they are one. A kiss is not just a kiss—it is a kiss with that person, a kiss after that conversation. And so on. Having sex with someone too soon is a betrayal of the essence of sex, which is to reconcile human bodies and souls. Having sex too soon is a cheapening of the phenomenon, by failing to be the best version of the phenomenon. Penelope was cheapening the phenomenon; I wasn’t. Therefore I was the winner.

Needless to say this was not a knockout punch. First, there was the inconvenient matter of Penelope herself. Odd as it may seem, presuming to have won an argument with her did little to make me forget about her. She was still the object of my daydreams, I still missed her, and the stinging just wouldn’t go away. To make matters worse, once I had gotten a little distance from my glorious self-satisfaction, the dry voice of Francesca made itself heard in my ear: I wasn’t being fair to Penelope. It wasn’t a fair conversation, because Penelope wasn’t a part of it.

Since I couldn’t speak with her—the angry email I had sent pretty much put an end to that—I had to settle for speaking on her behalf. And my imaginary Penelope-based interlocutor did an excellent job of poking holes in my argument. The main one was this: even if it is true that sex is never merely a bodily event, but always also a relation between persons, that doesn’t constrain you to a specific kind of relation. In other words, I wasn’t allowed to say that having sex too soon is a cheapening of sex by failing to be the best relation between persons—because in saying it I had sneaked in an understanding of what is “best.” Namely, a relation that develops slowly and exclusively.

“And did you think about friendship as a comparison?” Well, yes Penelope, I did. “Well, not enough.” She was willing to concede to me (in my imagination still, in case that wasn’t clear) that the ideal friendship is long-term and deep; she even conceded that exclusivity could be part of the ideal—maybe there can really only be one best friend. But didn’t I have to admit that there are long-term, deep friendships that start quickly? Okay, yes, I suppose I had to admit that. And didn’t I think it would be pretty odd to restrict my friendships to one at a time until I knew whether or not the friendship was going to get serious? Wouldn’t that make, say, parties difficult? Or team sports?

She had made an excellent point. Both of us saw romantic monogamy as a goal, and as an ideal. Again, one may not, which is a conversation for another time; but if one does, there is nothing about the synthesis view that prevents different ways of getting there. In Penelope’s mind—the real Penelope now, the one I terribly missed—when we did what we did on my final night in the city, it was very much an event of both body and soul for her. I couldn’t claim that she was “synthesizing” worse than I was; only differently. She was in it the way one is in the initial stages of a friendship—a friendship which one wishes to be greater but hasn’t yet arrived at. I was in it the way one is in a serious courtship. But, no matter the individual style, each of us was treating the other as a full person, and a person mysteriously fused with a body, as the theory would dictate.

I will not lie: in my gut I still thought she was wrong. I thought she was wrong, and it angered me, and I missed her. I was without an argument, though. So I did all I could: I congratulated myself for my intellectual honesty and tried to move on.

●

It may be best not to bother explaining how we ended up in the countryside again. The passage of time was more or less the thing, which in its healing allowed the two of us to get back in touch and set the inevitable in motion. If my angry email had prevented communication early on, it facilitated passion over the stretch. I would later discover that Penelope had fixated upon many of its words. I must have put some of my soul into it.

This time around, the snow was there lying on the ground before we arrived. And this time around there was an extra resident: Maria’s sister Lauren had given birth to a baby girl not too long after January’s events in the city, so now an eleven-month-old child was crawling around the house. (Or was she walking by then? I can’t remember.) The baby’s name was Libby. Lauren and Geoff were appropriately exhausted by her and relieved to be on vacation. Geoff was still obsessed with auto repair and was already looking forward to working on cars with his daughter. We were all excited to be together.

Everything went faster between Penelope and me than it had a year before. Within an hour we started looking at each other with the involuntary smile of the mutually captivated, easy for the others to see and also adorable to them. No need for tension, no need to wait several days. When we sneaked off to the kitchen and I stood before her and we exchanged a few sentences that didn’t make any sense, we knew it was time to adjourn. Then the captivation yielded the fruit proper to it. I will not soon forget the night, within which the body of Penelope seemed even more the realm of Penelope the person, the frustrating and challenging person now finally real instead of imaginary. I must have lent to my gestures and also to my nerves some part or whole of me that she welcomed. Otherwise, presumably, I wouldn’t have received the frustrating and challenging person in return. Upon the morning we talked for hours, about nothing really, just enjoying our truce, still smiling at each other’s faces.

In the afternoon the determined Maria insisted that we all climb a mountain together, Dan bringing the smirking resistance, Geoff bringing his child strapped to his back; the most of us hungover. Penelope and I held hands, dispossessed of our anger for once, and walked up the hill some distance back from Geoff and the bouncing Libby. The air was as crisp as could be. It seemed like we should have been happy.

First things first: neither she nor I is of the perpetually dissatisfied sort; we weren’t looking for the next challenge just because we’d gotten what we wanted. We might have been at a loss for things to say because we had nothing to argue about, but that couldn’t have been the only thing wrong—I knew it and so did she. We felt perhaps—outmatched. Here we were occupying a familial scene, but without really being part of the family. We were like little-leaguers playing in the big leagues: like two people who are having their first date in the toy-strewn living room of someone else’s house. That we were in the middle of the woods only made it more surreal.

I swear Dan could sense what was going on. In the evening when the group was down to the four of us, he proposed conversation, in his roundabout way. A person who is so acutely aware and so mischievous at the same time would be a real danger if he weren’t so caring—which is why I can forgive him for proposing, again in his roundabout way, that we talk about children. True, he and Maria might have been discussing it themselves earlier in the day; and it might have just been chance; but Penelope and I were touched to the quick, and before long the past repeated itself as it so often strives to do.

But not without variation: back in the bar in the city the raging of our group had been chaotic—my and Penelope’s preponderant unreason dragging everyone down, including the unfortunate Àstrid Bergès-Frisbey, bless her heart. This time there were clear sides from the beginning. Dan and I thought it was good to bring children into the world; Maria and Penelope thought it was not.

“You are being irresponsible.” “Look at what we’ve done to the planet.” “But don’t you want the happiness of a family?” “Raising children is noble.” “Raising children is boring.” “You guys are trying to get us to do the grunt work.” “Children are fun to be around.” “The rearing of children in the context of a family realizes the full potential of the human being.” “Career is more important.”

We weren’t drunk enough. We couldn’t have been because we had drunk too much the night before, which was why we were trying to have a real conversation in the first place. I got more annoyed at Penelope with every passing minute. Dan and Maria, I started to realize, had undergone the conversation in some form or other before. Maria may have been swept up back in the bar in the city, but she was not so now. She met her cherished Dan and his conversational mischief with her patience—those two were going to figure it out eventually. Penelope and I on the other hand were going to fight. We were going to stay up all night and it was going to be utter nonsense.

I have no memory of anything we said to each other in that bed, not a single thing. I’m sure this is because we couldn’t address whatever we wanted to address directly. Once we were by ourselves we couldn’t actually talk about children—we weren’t even a couple, how could we do that?—so we had to argue by proxy. Misdirected substitutes for the real thing don’t make for lasting memories. I do remember our bodies, though. I remember the sense of the squandered: her pale shoulders with the black fabric framing them, and my shoulders right alongside, and we were just lying on our backs facing the ceiling. It wasn’t sexual frustration, just a mute, pointless distance. We were doing the wrong thing.

When I woke up in the morning Penelope was not there. The reason why is nearly unbelievable to dwell upon, given the dialogue of our little ensemble from the night before, but it is the truth, charming and ironic. Penelope had heard the baby making noises down the hall in the early morning while we slept, so she woke up to go play with her. “I knew I really needed the sleep, but I needed Libby time more.” For goodness sakes, it was just a baby. “But those cheeks! Those cheeks!” I had to admit, the cheeks were something to wonder at—the child had inherited the striking high cheekbones of the mother and the baby fat cells had opportunistically colonized all the space underneath. But still now, it was just a baby. Later that day while the women were making cooing noises in the other room, Dan and I watched football. Dan played in high school and was explaining to me something about the defensive line that I had never understood. It was a very enjoyable experience. We all performed our roles unbelievably. No amount of self-awareness was going to stop it.

The world colluded to hasten Penelope and me to our inevitable end: to make two more days of sun and moon speed by, to send Lauren and Geoff and Libby home early, to require that Dan and Maria get on the subway to their apartment, all so that Penelope and I could find somewhere to stare at each other in fascination and anger. On this go-around it was in the city’s train station, treating a somewhat larger audience than usual to our obvious body language. We made zero progress in figuring out what was going to happen next: whether we would see each other again, whether we would stay away from other bodies, whether we cared enough or would admit that we cared enough. We just kept staring at our eyes—and I did finally realize that her eyes were sad not just when she looked down but because her eyes themselves were folded down, on the inside. But mine are folded down on the outside—and if we had children would the children’s eyes be folded down on the inside or the outside? Or both? There was no use. We had neglected to attend to the most obvious questions. We made no progress. We could not move forward, so, once again, we just walked away.

●

What a waste. That is the thought that ruled my mind upon returning home, for a good long while: Penelope and I had achieved mutual attraction, genuine mutual attraction, that very rare thing—and we had squandered it because of a silly argument. Though I knew the argument wasn’t entirely silly, or maybe not silly at all. It wasn’t even a single argument. First, we still hadn’t resolved the issue from the first phase of our entanglement: whether or not we were going to see other people. Then the most recent trip added a new obstacle. But what even was the obstacle? Not so simple. I knew it had something to do with the ill-fated conversation between the four of us—and I knew that the cheeks of the young Libby were somehow to blame. Beyond that, however, lay only confusion.

I had been directly asked by significant others before whether or not I wanted children, sometimes early on, sometimes later. I had also, of course, had serious conversations about the matter, with varying results. My conversations with Penelope, though—what were they? They were like conversations about conversations about children, or like some terribly distorted form of philosophical inquiry. Did I have a settled position? That night in the countryside I pushed the pro-children view, but needless to say I myself was somewhat clouded with regard to my own personal wishes. If a label is called for, I suppose I was “undecided”—swinging back and forth depending on the year, or the season. I did know that I found the idea of personal immortality particularly shoddy: that is, that we have sex and have families to pursue our own immortality, to “perpetuate our genes.” After all, if there’s something we can all agree on, it’s that scientists are clueless. Either way, it was certainly not the case that I had asked Penelope if she wanted children and she had said no. But I couldn’t deny that the two of us had found a new struggle. And, whatever the heck that struggle was, babies were involved.

●

Enter a new friend. Delaney is the partner of Francesca; the lives of the two had intertwined enough that I could now effortlessly become friends with Delaney, too. Delaney is a they, which is to say, they identify as “nonbinary” and prefer to be addressed accordingly. I won’t deny I found this odd at first, but the reasoning behind it was increasingly making sense to me. Delaney doesn’t want to be thought of as occupying a space between male and female, but rather as opting out of the system. Why, indeed, do we have to gender everything? What if someone just refused to participate, like dropping off the grid and refusing to use money? Here was a theorizer like me; and also like me, if I may claim it, not afraid to put words into action.

Although a much better listener. Kvetching about Penelope came naturally in Delaney’s presence, and I was granted some advice while we dined on pork chops at my house. First—“obviously,” they said—Penelope may feel you are imposing, attempting to control: hers is the gender that has fought to be free of imposition and control; the sexual revolution may even be defined as the separation of sex from reproduction, which had as a non-coincidental consequence a relaxation of the “management” of women’s bodies. She doesn’t want you bossing her about. Well yes, I said, I know that; my big talk about the inherent goodness of childbirth was not meant to subject her to my will; after all, Delaney, you know I reject all that unsubtle “biologism” anyway; just like you and Francesca do, as you would have to, given your situation. Yes, granted, but Penelope may still feel the way she does, and that may explain why the two of you are having bizarre and ferocious fights about children. Okay, fair enough.

The “situation” with Francesca, incidentally, was a good thing, not a bad thing. The situation was, in the first instance, that they were very happy together. Hurrah for that. But there was more: they had recently decided, after two and a half years together, that they wanted to get married, and, then, have children. The catch was—is this a “catch”?—that between the two of them there were two sets of female reproductive organs. As for how they were going to go about having children, that’s not relevant. The relevant thing, for me at least and also for Delaney, was that their strong feelings for each other could never be reduced to an aftereffect of their sexual organs in any simplistic, biologistic fashion. This is something really quite obvious if you stop to think about it, but something that nevertheless tends to get drowned out in discourse that is, for lack of a better word, heteronormative.

Delaney had thought and read extensively about the matter, and reminded me that night of their keen interest in the ancient Greeks. A fan of K. J. Dover’s Greek Homosexuality, they had once shown me all the pictures of Greek pottery within: vase paintings depicting men fondling the genitals of younger men, boys preparing for anal sex with each other, men rubbing their penises (“intercrurally”) between the thighs of other men. “Imagine a society in which the ideal of beauty, the object of obsession, is not the body of the young woman, but the body of the young man. Imagine if in modern America successful businessmen were as a rule fantasizing about college boys, and not college girls.” Admittedly, in ancient Greece these were not always college boys, but much younger boys—or at least scholarly debate continues about this—but something fundamental remains: the Greeks were, in Delaney’s words, “just so gay.” And to this day we still underestimate the importance of that, and it is important because it shows that erotic obsession, the captivation of one person by another, need not have anything to do with the reproduction of the species; and particularly because there was once upon the earth an entire culture spellbound by the beauty of men—an entire culture, not just the errant few—and not just any culture, but the very one that served as the cradle of Western philosophy.

But why, Delaney, why? Why do I feel the way I do about Penelope? If it is not my biology duping me into sex and a nuclear family then what is it? We had been at the table for a while and were tiring of all the serious talk. So when we finished gnawing the bones of the pork chops as clean as they would go (please don’t gender this behavior), we sat back in our laziness, and I got to hear some of the story of Delaney and Francesca’s slow-moving and adorable romance, this time from Delaney. The story was familiar—it was the same story, even if from a different perspective—but there was one new detail that I had never heard. There was a moment, a singular moment, when Delaney more or less knew that they were done for, that the game was up. The two had been friends before they became a couple, so the moment in question was not the moment when they first met; nor was it a particularly revealing utterance that passed from Francesca to Delaney, because they had already known each other fairly closely. One day, not a special day, simply another day, Delaney just happened to see a photograph of Francesca; in the photograph Francesca was not looking down, but was looking right at the camera—and her mouth was captured at just the moment to reveal the maximum wryness of her smile, Francesca’s trademark wry smile. “All of a sudden all the pieces came together and I knew. And I remember a particular phrase jumped into my head. ‘Damn it, I’m in trouble.’ Not that I was really in trouble, but you know what I mean. I was in trouble.” As Delaney said this at my dinner table two and a half years after it happened, I thought to ask something not a little strange, which in another context might have seemed goading but at my dinner table seemed just right: “When you saw the picture were you thinking about children?” Delaney’s answer: “No. But it felt like the future.” And that was all I needed to hear.

●

The text of Plato’s that deals most explicitly and thoroughly with sex is the Symposium. In my mind it has always seemed like an alternative of sorts to the Plato of the Phaedo—just as, in past scholarly generations, it was a black-sheep dialogue within Plato’s corpus, scandalously lascivious; confined even, as legend would have it, to the back rooms of bookstores far from the philosophy section. I had a nice neat account of the Symposium. If dialogues like the Phaedo or the Republic give us respectable, intellectually rigorous paths to the “Forms”—the transcendent realm where we finally get to see the Good itself instead of its secondary manifestations here on earth—the Symposium gives us another option: eros. Physical attraction, counterintuitively enough, can be an approach to the very non-physical realm of the Forms. There is a ladder: you begin with an erotic fixation on one particular face and body; you then become attached to physical beauty in general; then you realize that souls are more beautiful than faces and bodies so you focus on those for a while; and upwards, until you get to the beauty of knowledge; and then eventually the knowledge of the Beautiful itself—or the Good itself, because there is no difference. In other words, physical attraction may ensnare the breeders and commoners of this world when they go for a roll in the hay, but the philosopher knows to move beyond it, to use it as a springboard to the highest things.

In my nice neat picture of the Symposium, I congratulated Plato for at least considering this alternative path to Platonism; the book is a welcome change of pace if you’ve been reading the Phaedo or the Republic. I did congratulate Plato but condemned him all the same—for once again degrading the body, and giving philosophy the bad name it has among the Penelopes of this world. But a text packed with riches has a habit of creeping its way back into your thoughts and unsettling them, as this one did mine after the dinner with Delaney.

A room full of wealthy men, aesthetically and intellectually inclined, have been making sexual confessions to each other—though without the details, and in the guise of encomia to the Greek god named Eros. When it comes Socrates’s turn to speak, he relates the speech of someone else: a woman named Diotima, who once taught him all he needed to know about ta erôtica, the things of eros. Armed with the excuse that someone else is his source (and a woman no less), Socrates proceeds to rip apart the adulatory, but human, all-too-human tributes to Eros delivered prior to him—by climbing the ladder to the Good, upon which admiration for bodies is the lowest rung, and absent from which is actual, consummated sex. Not even the speech of Pausanias is exempted from the critique, he who proposes that Athenian gentlemen shouldn’t be having sex with boys but with young men who have their wits about them; he who walks the walk by being the virtuous and longtime companion of the successful and very good-looking Agathon. Shortly after the secondhand speech of Diotima we learn that Socrates too walks the walk, because the beautiful and powerful Alcibiades bursts into the room and, drunken, tells everyone the story of the time Socrates refused to have sex with him. All in all then, the same old message from Socrates.

But there is something else: before the theory of the ladder, which over the centuries has attained legendary status as the point of the book, Diotima argues for a different conclusion. After getting Socrates to agree that eros is the desire for the good—because the god Eros himself cannot be fully good, or else he would have no desire for the good—she lets drop a small addition, easily agreed to because of the way she has maneuvered to set up this very moment: eros is not only desire to possess the good, but desire to possess the good for all time. And from here Diotima is off to the races. For how do mortal beings possess something for all time? Through procreating, because that is how mortal beings partake of immortality.

Does procreation refer only to the creation of a child using the cells of a man and a woman? You can bet not—not in a culture besotted with philosophy and male beauty. And not in a culture that greatly honors statecraft: Diotima is sure to mention Lycurgus, the founder of Sparta, and Solon, the founder of Athens, who have left behind quite beautiful “children.” Great too, on a less great scale, are the virtues passed from a single human being to another single human being, biologically related or not—like the virtues presumably passed on from Pausanias to his companion Agathon, who has just been crowned one of the greatest of Athenian playwrights. The good makes its way on into the future.

As far as I am concerned, this is it. For very much of my life I have wanted to know: What is that feeling? What, really what, do I want when I become singularly captivated by another being? The poets and novelists and filmmakers had a lot to tell me—but I was looking for theory also, and unabashedly. I tried psychoanalysis, for so long, Freud and Lacan, but they were missing something, as psychoanalysis always seems to miss something, too eager for complexity. It took the paradoxical simplicity and depth of the ancients to bring the truth home to me. When I become singularly captivated by another human being, what I want is to possess the good for all time. I want that she and I create something good and pass it on to the future. That is why, when you meet someone just right for you, it feels like the future; and that is why the past can open up at the same time, with the thought that you have always known each other—because time is stretching both forward and backward. And we can have this feeling not only when we want a family with our own cells, but also when we want to adopt—or when children aren’t involved at all, when we want to crusade for the good alongside the person who is just right for us.

And the body? Well here is the best part. It is the part that Socrates and Diotima and Plato leave out, and I very much disagree with them. Nowadays when I read the Symposium I ache for them, even. I ache for Diotima and wonder if maybe she should have tried having sex with someone, though maybe not with Socrates. And who knows, maybe Socrates should have had sex with Alcibiades. Either way, sex is not only bodily, as my intellectual journey had well convinced me: my “synthesis” theory and my conviction that every sexual relation is a relation between persons. This is all still true, I think. But now there is more. Sex with someone can be a celebration not just of your relation with that person, an instantiation of that relation in bodily form; sex can be a celebration of the good that you and the other person want to pass on. Or, put a better way, the good can be what draws us into the bodily relation in the first place. Or, put bluntly: we can be sexually aroused by the good.

This borders on an idea familiar to most of us already, the idea that we could find someone sexy because they are good at something. But it is a further step to say that, even after initially finding someone sexy because of something good, we then go into the sexual act trying to have sex with whatever is good about them. I do want to say this, or at least metaphorically, with one of those metaphors that may not be a metaphor. I want to say that we could be aroused by their mathematical ability, or their gracefulness, or their biting wit—but because we can’t literally have sex with their excellence—penetrate it, wrap ourselves around it, massage it, whatever—we can be thankful that they also have a body.

What a long and tricky process, no? To meet someone, to get to know them, to want to possess the good for all time by passing it down with them, and to celebrate and instantiate this in the moment of sex. It’s almost as if… one couldn’t do it in a single night. Surely it must take time, letting the body of another human being gradually take on this responsibility, the responsibility of being a physical symbol of a spiritual craving.

I learned from my earlier researches that in sex the soul makes itself flesh and the flesh becomes ensouled. In the fulfillment of eros, the following-through on the captivation with another person, it is not just the soul generally speaking that is made flesh, it is the soul at its very best, the best of that soul, ready to be immortalized. When I have sex with someone about whom I have this feeling it is as if I say to her: “You are good, and I want to take the good in you and pass it on, which I find sexually arousing.” Thankfully I don’t say things like that out loud, nor do I recommend doing so. Nor does one need to say them, because the body says them. And I have no idea how the body could say those things to another body it has just met; that is a gap that requires time for the crossing.

●

It would be nice if this settled everything, but it didn’t. But in a way it did—because I finally came to a settlement; just an unsettled settlement. And that is where I am now.

On the night in the city, the night I lost control of myself, Penelope cried. I would learn more about the source of those tears in the time to come: a past she was moving beyond, however stumblingly, as we all do it. The only thing one needs to know about her past is a quite simple thing, namely, that once upon a time she had given herself to another person and to her mutual future with him, and—surprise that is not a surprise—she had done so not at all after the model of my own chastity. And yet Zeus did not strike them down with thunderbolts, and the world did not come to an end; their romance was still a romance, full-blooded and true. Once again, then, in the light of this stubborn, Penelope-based piece of reality, Penelope proved herself the great confounder of my theorizing.

The insight into the Symposium, if I may be so bold, remains: my life is forever the better, or at the very least, I am forever the wiser for understanding the meaning of my own eros, at once so plaguing and so dear to me. But logically speaking, even given my insight, there is nothing stopping anyone from proceeding in romance in the way that Penelope did. Two people can go about the long process of negotiating body and soul for the sake of the good, can even go about it painstakingly slowly—but can do it later rather than sooner. They can do it after having had sex for ten years, with ten other people, in ten different cities; theoretically, it shouldn’t matter, even by my own reasoning. I had been sneaking in assumptions about the way I liked to do things: assuming that the best way to negotiate body and soul is to do it immediately and faithfully. But one need not. One can accept my hypothesis, share in my breakthrough about eros—without applying it in the same way I (unthinkingly) did. Just because earlier sexual relations are conducted without an eye to the perpetual possession of the good doesn’t mean that later ones cannot be. I myself find that way of proceeding intolerable; I believe, and believe deeply, that you only get one chance. But that is just me.

So where am I, then? Where has she left me? Just the victim of a trifling disagreement about sex that happened to spin out of control? There is more going on than that. She and I like to proceed differently because we are different kinds of person, and that is no small thing. To someone like Penelope the past is something relinquishable, and something mutable: that she was so nervous when I kissed her was no longer important; that she was with someone else soon afterwards was no longer important. To me all of these events and details are the roots from which a tree grows and which therefore shape the tree. How could they not? No tree is unaffected by what stands beneath it. But right back from her side would come words like: what is important is not how you start but where you end up. How could it not be? You need to let go of the past. And there would be nothing to say back to those words, other than more words like the ones just said. And more words like her words would come back thereafter. And on and on.

What I think now is that I have reached bedrock. Or rather, I have reached the fault line splitting the bedrock, lying underneath all the words and all the arguments. For some of us the opening gestures can never be forgotten; what we did with our bodies will always shape what is to come, and we want to look back on the origins with fondness. For others of us this just isn’t important, or at least not until, well, it is important. And this difference is but the manifestation within romance of another, very deep difference between human beings—about purity and impurity, memory and futurity, loss and progress. I am of the type for whom all that is earlier permeates what is later; it would hardly be a surprise to discover, for example, that I do not like change. She is of the type for whom the future is not enslaved to the past; it would hardly be a surprise to discover, for example, that she does like change.

Even to dwell upon it calls up the protest yet again, but I must resist. I want to yell out at her—Penelope, the living, breathing stumbling block—but there is no use. In most of my moments I know this, and I do whatever I can to nurture what I think is a very healthy alternative obsession, my obsession with the virtue of skepticism. I behold her; I behold that person Penelope, and I utter to myself the magic words: she is different from me. Period—that’s the end of it. There is no use trying to change her; and, just as important, there is no use for her in feeling offended that I am different. The difference is a difference in temperament, a fault line in the bedrock. It is incredibly easy to utter words to this effect; it is incredibly difficult to practice what one preaches. And it is even more difficult when one’s very eros—one’s very future—is at stake. Am I boasting of the greatness of my trials? Maybe a little. But I do at least acknowledge that they are trials. I no less than the rest of us am persistently visited by the notorious, secret, prideful thought: “yes, but in the end I am right and everyone else is wrong.” Which somehow one still believes even in full view of the fact that everyone else believes it too. I think real tolerance is difficult because you have to tolerate disagreement not just temporarily, but permanently. You have to be able to accept that someday you will die and in the meantime nothing at all will have changed, and the matter will never, not ever, be resolved. It is a weird skill to have; it requires playing some kind of delicate game with time. I still have not found any valid generalizations about who has the skill and who doesn’t. Rich and poor, young and old, whatever. I do know that it is not just an inborn talent, since you can acquire it; but unfortunately I don’t really know how exactly you do acquire it. I know one more thing though: when someone is good at it, then that sure is delightful. I think we should praise the virtue more than we do.

●

I saw her once more. Dan and Maria, as one might guess, had a wedding, and Penelope and I were unavoidably guests. The wedding was in the countryside, but we two antagonists were spared Maria’s family house and all the specters it contained; we were banished to separate hotels and encountered each other only when surrounded by other people.

In the time intervening, between my resignation to our ultimate disunity and the summons into her presence at the wedding, I became more and more entrenched—or liberated, whichever—in my new position. Such that I could, for example, say to myself and actually mean things like: I am not interested in having sex with anybody unless it is the last person I ever have sex with. Nowadays, when I am presented with options that I know are not truly options, I have a kind of sight into the way such an option will end—not well, and the unhappy result leaps back from the future to infect my present. What in the old days would have been pleasure followed by disappointment is now just disappointment from the start. I’ve been down the wrong road enough to have secured a wisdom that is not merely intellectual but fully visceral.

Well, for the most part at least. Among the exceptions would certainly be Penelope herself, in a summer dress, with her hair back upon her head, showing her neck and shoulders.

I really had made peace with myself about her. The more I settled into my new position the easier it became to accept that we were a potentiality that would never become actual. Our difference just wasn’t all that small a difference. I even came to think that there were probably other differences with their own deeper dangers. What would our shared good have been anyway? Did we ever really work on that, see into that? We disagreed on that too, and in the early stages I at least dedicated a considerable amount of background thought to finding some overlap between us: the project we might set out on together, the good we might pass down to the future despite our apparent conflict. What was the conflict? It doesn’t much matter. Maybe it had something to do with animals—maybe she was a dedicated vegan and I wasn’t, and that was a sign of something deeper. Maybe it was that. But it doesn’t much matter.

The sight of Penelope in a summer dress had to mean something, though—my physical desire could not be separate from my desire for her as a person. Some part of her soul must have delighted me. Thankfully this time I figured out quickly what it was. Immediately, in fact.

I would like to say she was standing under a dim red light when I saw her, and the dim red light called to mind the scene in her bedroom, when I was shaking uncontrollably, and I tried to hide but I failed and she found me. I would like to say that, but it would be untrue. Only the sight of her in a summer dress with her hair back upon her head brought me back to that room. When it did, I felt a flood of gratefulness. Gratefulness for the way she was in that room, yes, but gratefulness for the way she was, to some extent, all the time when I was around her. She made me feel known—me, one of life’s perpetually difficult customers, always hiding out, difficult to reach. How did she do it? Her words were not what found me; interesting as her words were, they had, all too often, the power to repel me. It could only have been something under the surface, then: a set of abilities hard to define, like the timbre of a voice, the length of a pause after a sentence, or the exact pressure of a hand reaching from behind me to calm me down. Or—the pressure from a pair of sad eyes looking into mine. Thus did the past unfold for me; thus did I come to appreciate Penelope’s true and gleaming capacity. Whatever this capacity is, I do not have it. I also don’t really know how exactly I can acquire it. I know, however, that I will try, and I know that it is worthy so to do.

From the first sight of Penelope and the feelings she occasioned, I made it my task at the wedding to communicate my thanks to her. I probably failed. The task may not have been foolish through and through, but it was surely ill-timed, for the moment of our openness to each other had passed, and the moment of our moving on had long since arrived. The world agrees: my friends Francesca and Delaney now have a child, the three of them residing in the future that two of them sensed from the beginning; and rumors of children float around Dan and Maria as well, much talk of their project, the expectation heightened as each season rolls by. Time unfolds along with all its accustomed transactions. I, meanwhile, happy among people who love me, and ever grateful to those who have known me, cast a long gaze forward, and contemplate what it is to let go.

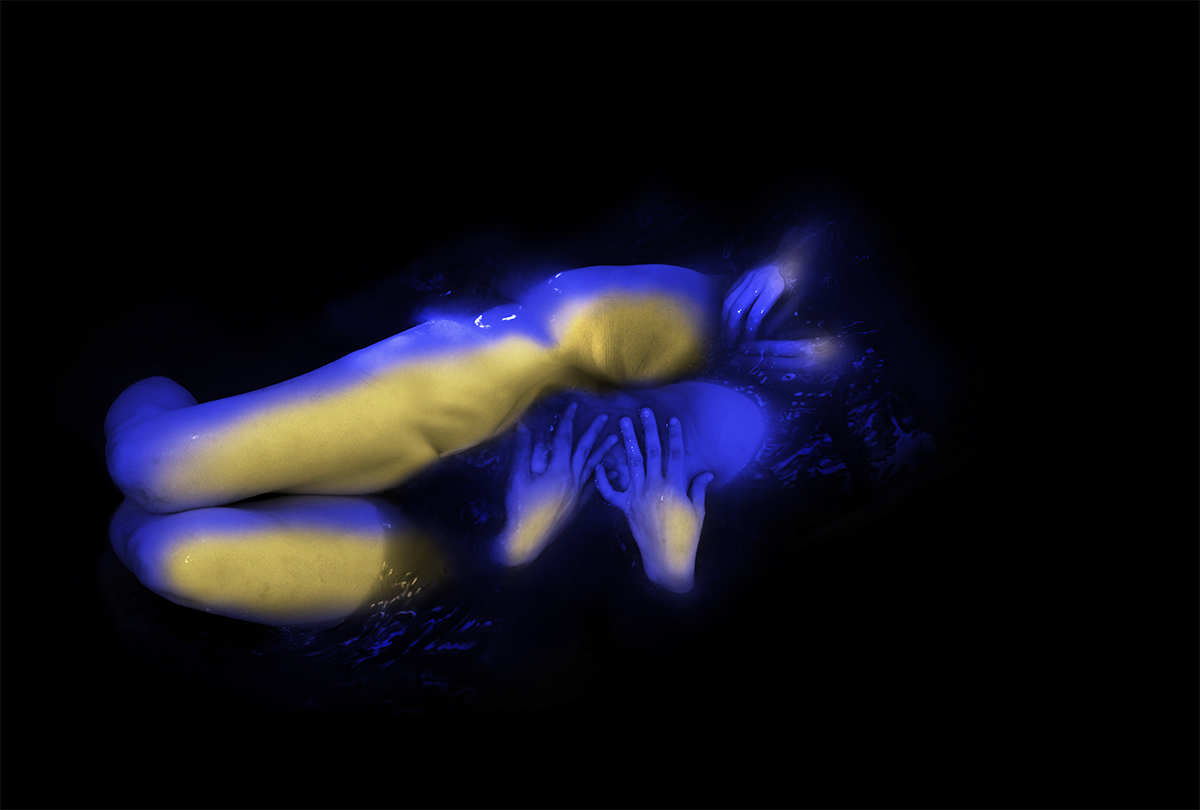

Art credit: Matt Wisniewski. Strange Matter #11, 2020;Strange Matter #3, 2018; Strange Matter #12, 2020. All images courtesy of the artist.

Here is where I am now: I am not interested in having sex with anybody unless it is the last person I ever have sex with. That is the ideal at least. I know there could be exceptions, when I do things I don’t truly want to do. I know there could be broken hearts—because you can’t always know you want to stay with someone forever before you have sex with them, can you? It wasn’t always this way. I was no enemy of casual sex; I did it when called to. But there was always some unease with it, some misgiving that I couldn’t define, or, perhaps, wasn’t even aware of. My life of late has been in no small part the story of coming to terms with my unease.

Like all stories, or at least the good ones, this is a story about another person. It is a she, and she is a joy to hold because we fit just right together. She is also uncommonly, eternally stubborn. She would probably call me stubborn too; I accept that. For over a year, despite not spending all that much time together, and despite remaining, on some deep level, strangers, we were each of us a thorn in the other’s side. And for over a year we were each of us also, each for the other, a figure of great fascination, a preoccupation and a pleasure. It is difficult to say whether the fascination was caused by the thorniness, or the other way around. It is easy to say what we argued about: we argued about sex. Which, as it turns out, is a much bigger argument than we ever could have guessed.

●

There was a prehistory for us. I have a close friend named Dan, and Dan’s girlfriend is Maria, and a close friend of Maria is Penelope. Penelope is her. Two years before she and I met, Dan told me on the phone: “I’ve got a girl for you.” He indicated how I could find a photograph, and I found one; if there was some kind of gleam in my eye when I looked, I don’t remember, even if I do remember being vaguely struck. Dan was quick with a warning: Penelope and I would probably disagree a lot. But underneath the surface—so he sensed, my friend Dan with his knack for character—there was “something there.” A something to do with our respective idealistic natures. Or maybe some other something. Just something. So I counted myself interested in meeting this Penelope, this one with her eyes turned down in her photograph and her undefined communion with me. Then she was filed away and I went back to the rest of my life.

When we met, two years later, it was cold. Dan and Maria had invited me to her family’s house in the countryside just before Christmas, to be joined by her sister and brother-in-law. My friend Dan—devious, to go along with his knack for character—neglected to tell me that a certain young lady was invited until an hour before I got in my car. The fix was in. My trip became a little more enjoyable, the scenery along the road looked just a little better.