Toward the end of my teens, it began to dawn on me that my face was probably fully formed. That no radical change was forthcoming. That even back when I still held out hope, my features were meanwhile settling, treacherous, into a mediocrity which surprised, humiliated, crushed me. In other words, I was not going to be any great beauty. I was only going to be what I was: attractive occasionally, like most people, relative to whoever happened to stand nearby. I was horrified; I couldn’t get over it. Being average-looking is, by definition, completely normal. Why hadn’t anyone prepared me for it?

I could not have discovered I was plain without discovering K was pretty. She is my friend of many years. Back then, it obsesses me: how we make each other exist. We attend elementary school together, then high school. She enrolls at a nearby college. Her tall grants me my short; my plump her skinny; her leonine features my pedestrian ones. I resent her as much as I exult in her company. In between us, and without words for it, the female universe dilates, a continuum whose comparative alchemy seems designed to confront me, make me suffer, lift her up. Her protagonism diminishes me, or does it? I confuse myself for a long time thinking I am the planet, and K is the sun. It takes me a long time to forgive her.

Comparison steals my joy, but it also gives me a narrative. All in all, it feels radical to make a world together, she and I, a silent tournament of first kisses, compliments, report cards. I live at a fixed point from K, her lucky arms, her lucky neck, her lucky elbows. I pursue beautiful friends like some women do men who will strike them in bed at night. On account of our addictive relativity. On account of my envy, which I’ve made, like many women, the secret passion of my life.

●

There’s something gorgeously petty about many women’s lives. They’re not trying to be great. They’re trying to be better. It’s why women diet together; dye their hair light, then dark, then light again; dress for each other; race to get engaged; wait to get divorced; find a taken man more attractive than a free one. Become girlbosses in droves and then give it up. A woman can spend her whole life in real or imagined competition with her friends, finding herself in the gaps between them. Especially in the game of looks, there is no excellence that is not another woman’s inadequacy, no abundance that does not mean lack. A great beauty is discovered, like crude oil, or gold. That means in a parched desert, or a dirty riverbed, where the rest of us must languish. Our democratic sensibility commands us to raze all unfairness. Yet the way we sacralize beauty, our treatment of the women who try to level it, our satisfaction when no one can, calls our bluff.

For me, the humiliations stack up. I nurse them like little children. I pick at them like scabs. The horrid boy I desperately love, who pretends to love me, studying K’s legs on the trampoline. We are seventeen, and I study them too. Up and down, slender, hairless, vanishing up the thighs, into the sun. Later he sends her a message on Facebook. She does nothing to betray me. What I want is for those legs and the mat of the trampoline to go rigid, to snap, for her bones to spray and splinter, to pierce me through the eyes, so I cannot look at either of us anymore.

Or, a couple years later, when I believe I’ve matured, gotten over it, displaying my fake ID at a college party. It’s my friend’s, I explain. It’s K’s. How funny. It works, we look just enough alike. A drunken classmate laughs. “Yes,” he says. “Except she’s hotter than you.” My face silences him, then the room. His words spread my legs, pass a hand through me, find something dying. He apologizes until I console him. I return to my dorm and drown in abjection, almost pleasurably at this point. I’d like to call my mother, whom I resemble. Except that in all of our talks of puberty, she omitted this. She gave me my face and felt guilty; I had to learn for myself how my suffering held something up.

My own inglorious adolescence ends with me dumped, over brunch, at twenty. He has a strong jaw which dazes and a soft birthmark, near the mouth. He is ten years older than me. That last bit is not the part that hurts. It’s that he’s telling me about another girl. “She’s amazing,” he says. “I haven’t felt like this in a long time.” I think of what we’ve done for a long time and I go to the bathroom and vomit. When I come back he’s still speaking. I wonder, in silence, what it would be like to be the sort of girl about whom they say, he can’t shut up about her. “She’s a writer,” he tells me, with love in his eyes. He looks so handsome, I want to kiss him, exactly now, when, because, he can’t shut up about her. I go home, look her up, write a poem, get over him as soon as I get it published, thinking vaguely, see, there, that was easy, take that—I might be less lovely, but there are other competitions, I can be a writer too.

●

In those bad years I read and reread a story by Émile Zola called “Rentafoil.” A satire, it tells of a wicked entrepreneur, Durandeau, who cooks up a nasty scheme of renting out ugly women as living foils for better-looking ones. Strolling around nineteenth-century Paris, observing “two girls tripping along,” one pretty and one ugly, Durandeau realizes that the ugly woman is an “adornment worn” by her prettier companion. She makes her look good. Her asymmetry sets off her symmetry; her dull face, her shining one. For five francs an hour, Durandeau’s agency makes available to the “upper crust” ugly women to drag about town. There’s nothing like the “pleasure of a pretty woman leaning on the arm of an ugly one,” knowing herself enhanced. And nothing like the sorrow of their Foils, who “fret and fume and sob” at night. Finally, the narrator confesses that he “may write the Secret Memoirs of a Foil,” inspired by one “terribly jealous” employee, lovesick and bitter, who reads too much. “Can you imagine her resentment?” the narrator asks. I could.

But take the first plain girl that inspires Durandeau. She isn’t employed or receiving a salary, but she must be getting something. Or else why on earth would she tolerate it? The unfairness of beauty, the pinch of being its friend. The comforting fable says: the great beauty hurts us like a splinter but helps us like a measuring stick to understand ourselves. Affords us insight, depth. An opportunity to compensate. After all, it’s the plain woman about whom the narrator of “Rentafoil” wants to write, not the beautiful one. I study that poem by Yeats. Waxing about “Two girls in silk kimonos, both / Beautiful, one a gazelle.” How casual, I think. How vicious. If she read that, the girl who wasn’t a gazelle, she probably never recovered. It strikes me only later that she might not have wanted to. For what we tolerate of beauty—that pinch—is also, curiously, what we reap from it.

From Austen to Ferrante, women’s literature is ripe with dyads of women, made up of a beautiful half and a less beautiful half. Here, the arbitrariness of beauty plays out in long, anguished plots, games of chutes and ladders, whereby some women find themselves socially, magically, economically mobile, and others do not, at least not so easily. We recognize the “winner” as soon as we read what she looks like. In first-person stories, more often than not, it’s not the narrator. These plain heroines yearn for, resent, are fascinated by, love, hate, cannot stay away from, their more beautiful, fortunate counterparts. They articulate a precisely feminine pain I know well, worse than menstrual cramps. A sense of one’s own plainness. Inferiority. An envy so profound and wistful it is almost sexually charged.

This tone in women’s literature, this snake twist of the belly that signals envy in the same place as desire, engrosses me. Some of the most exquisite passages of eroticism are in the voice of women envious of other women. Wanting them? Sometimes. Wanting to be them? Naturally. I watch K do the dishes, in her bikini top and her peasant skirt, and the tight abdomen that is an insult, and the overhead light that haloes her hair, careless, the soap, the suds, the satisfaction she must feel. In that moment, I want to take the dishcloth and wipe my face from the face of the earth.

●

I read, at first, in search of consolation prizes.

In the Neapolitan quartet, Elena Ferrante shows how unfairness, like money, accumulates; beauty forms the mask of what crushes, monopolizes, outshines. Lenù, the narrator, is a dogged teacher’s pet, born into poverty, who becomes a successful feminist writer mainly thanks to her diligence. Lila, her best friend, is a wünderkind. Along with “virtuosity” and the power to invent, Lila gets “an odor of wildness” and an “energy that dazed” men, “like the swelling sound of beauty arriving” to Naples. Lenù gets pimples and glasses. Some sirocco wind is always at Lila’s back, making her wealthy; making her loved; making her angry, brave, righteous; almost a model, or perhaps an actress, except she is married so young; the hero, the innovator, the victim, the star.

My insistence on fairness nearly convinces me that, in losing, Lenù must be winning something else. After all, what she envies of Lila is exactly what Lila, in turn, provides her with: content. That’s why Lenù sticks around. When a woman resembles a movie star, her conditions of living take cinematic turns. Life occurs to her quickly, impossibly, like the montage of romance, while the plainer girl plods along, a subject better suited to a documentary. But Lila’s shimmering existence seeps into Lenù’s. The “daily exercise” of noting the “convergences and divergences” between them, the “lines between moments and events” and those deus ex machinas which evade one and land on the other. Envy makes Lenù observant, a student of contrast. Which is to say a better writer—good thing, since we all write ourselves. While everyone plays the main character of their own lives, the plain girl is forced to be a little more thoughtful. She’d be written by Woolf, not Hemingway.

Doesn’t being graceful just mean not having to think? Nothing is laborious, everything is effortless, every morning Christmas morning since puberty left so many gifts. The awkward plain girl is driven, instead, to self-obsession. To make a craft of her posture, her eating habits, her odor, her laugh, why they fail her, how to improve them, the variations that make them superior and winsome in that favored someone else. The symbol of being a plain girl is a heart trying hard. Erasing, scribbling. Romanticizing her contours. Narrativizing her lack.

This is the bone Ferrante throws the plain girls, only to toss it out. Lenù becomes the writer, sure, but even what shines in her writing, we are given to understand, derives from Lila’s unpublished work, effortless, with a “force of seduction” Lenù can only contain, transmit, emulate, as if tracing the path of a comet with her stubby pencil. Whatever prompt for reflection or observation Lenù extracts from Lila, Lila extracts from Lenù too. In other words, don’t kid yourself, even Lenù’s silver lining lies in Lila’s shadow.

Perhaps the plight of the plain girl is redeemed by its realism. Women age terribly. The homely woman gets there first. Everyone knows the genetically blessed woman remains better insulated, to some degree, from humiliation, male disdain, poverty. That Joan Didion thought the streetlights would turn green for her strikes one as rather unhinged, until one sees her photograph, and knows it with certainty. Beauty opens like a trapdoor, to second chances, the benefit of the doubt, a job you’re unqualified for, someone who will marry you, if you so require. The cost may be a life out of touch. The plain woman operates under fewer illusions, always a little closer to the truth. In Wives and Daughters, Elizabeth Gaskell’s last, unfinished Victorian novel, provincial Molly finds herself the stepsister of worldly Cynthia, whose “beautiful, tall, swaying figure” brews predictable scandal and then sidesteps it, at Molly’s cost. For Cynthia wears “her armor of magic”—they all do, letting her slip, eellike, out of the usual scrapes, if only to then get into others. The unfortunate and nameless protagonist of Marguerite Duras’s The Lover, fifteen, compares herself to her classmate, Hélène Lagonelle. Hélène is a virgin, her body “the most beautiful of all the things given by God.” One feels, as one reads, the monsoon brewing. Hélène is “infinitely more marriageable,” but “doesn’t know” what the girl with no name does, of typical survival. Of course not. We’ve read what she looks like. Such knowledge might be worth the price of plainness, if only it didn’t require knowing women like Hélène. “She makes you want to kill her,” the girl confesses.

And what of that final possible solace: that beauty is attended by its own kind of suffering. Objectification. Underestimation. Abuse. Too many men and their egos. Even more seductive an idea: Do beauty’s higher highs mean lower lows? Does whatever miracle that plucks a beauty from the crowd set her up, too, for catastrophe? Crowns her a princess just to cut off her head? Look at Lila in the Neapolitan quartet; she might get special treatment, but she also gets beaten. She loses a child; her anguish is as sharp as her fine bones. Plain Lenù studies, applies herself to an uphill climb, a subdued figure against a headwind, yes, but she does end up, on the whole, better off.

Yet whatever delusional peace this line of inquiry brings us, Ferrante snatches back. No suffering of Lila’s stops Lenù from being jealous of her. “What more do you want?” Lenù asks Lila, bitterly. But what more does Lenù want of Lila? The answer is as simple and complicated, as shallow and treacherously deep, as: Lila’s face, Lila’s body. The Neapolitan quartet undercuts that old, soothing sentence, that compulsive effort to compensate, to equalize, one that my own brother noted I used spitefully in high school, whenever he mentioned a pretty girl: “Yes, she’s beautiful, but…” But nothing. We might identify with Lenù, but who reads Ferrante’s books and wants to be anyone but Lila? It’s not all good, it’s just everything.

●

I fly from Marrakech to London. I wait in line at the airport as a young man is berating a young woman, who begins to cry. I board and discover that by some hellish providence, the woman is sitting next to me. I’m looking good these days, perhaps because I’m finally well-loved, but that’s for another story. The girl tells me everything. She lists atrocities but saves, in a quiet voice, the worst for last. “He said I was average-looking.” I can hardly stand to meet her eyes. The boy is a few rows behind us, chatting up a pretty stranger. “You’re not,” I say. “It doesn’t matter.” I touch her back. Something is happening between us, very wonderful and sad. Then in the middle of her sobs she holds her hands up, and laughs a little. “I’m sorry,” she says, and then crying harder, her voice breaking: “It’s just your hair. It looks so… beautiful. It seems so… soft.” It’s hurting her. I put it up.

In the first of the Neapolitan novels, Ferrante places a wealthy, “superior” girl in green—green shoes, green jacket, green bowler hat—green, the color of envy, in Lenù and Lila’s path. By the second book Lila remains worried over her. “You’re much prettier than the girl in green,” Lenù consoles her, then thinks, “It’s not true, I’m lying.”

●

Some evenings I watch the reality TV show Love Is Blind, where the hierarchy of beauty I resent is toppled, then reasserted, to my masochistic schadenfreude. Singles date without laying eyes on each other, only meeting after becoming engaged. No one fares worse in the program than the unattractive woman paired with the better-looking man. Consider her fate as I do, on the couch, over ice cream. Alone, she meets her new fiancé. He kisses, compliments, gropes her, perhaps sincerely. She’s gorgeous, he says. She isn’t. We eye him as suspiciously as she is beside herself with joy. Days later, at a pool party, the couples reconvene. He sees the other women for the first time, and beside them, her, the one he chose, at last in context. His face falls. It is precisely at this moment he ceases to love her.

Other evenings I switch on I Am Georgina, on Netflix. It infuriates me, her story, the whole premise, Georgina Rodríguez, the surprising partner of football superstar Cristiano Ronaldo. How, like millions of other women, she once worked in a shop, playing nice with her customers, despising her days. How, unlike millions of other women, there existed something in her face so naturally beautiful as to unnerve Ronaldo, to stop him in his tracks when shopping, to impel him to take an interest in her. To move her into his mansions, where she might live in luxury, taking care of his mysterious, surrogate-born children, accruing Instagram followers, purses, a reality show, the guiltless blessings of the born lucky. She goes to work by bus. She leaves by Bugatti, forever. It riles me up. I turn on the television and I watch her and watch her until I love her and hate her, as I might a friend.

●

At the first faint signs of aging, relentless K is swift to get work done. Botox. It rankles me. We’re 26 now; isn’t she tired? Energy is neither created nor destroyed, so I search my forehead for her wrinkles and find them. I visit her dermatologist, taking the long way, dragging my feet, vain enough to have booked the appointment but not so vain I would have gone unprompted. The doctor prescribes me: one syringe of filler, to raise me from one level to another, as she did my friend. I infer: two syringes, to close our gap, make us level. An old wish. I nod, close my eyes, grip the table. Beauty, incoming. She readies the needle, then the first injection site. My eyes sting, I think, at the scent of the alcohol pad. Then some misgiving in my face stops her. “You know,” she says, slowly, “You and K are not the same, you are different types of… attractive, you don’t need to rush this.” Implicitly: I’m not as pretty. I have no such pressure, to prejuvenate, or invest. I sit up. The insult frees me. I could almost kiss her. I float to my car and drive home dancing, catching my flaws in the rearview mirror, like darlings an editor didn’t make me cut.

I’d gone to finally compete with K but settled for comparison, that poignant force that had always pushed me, turned my page, compelled me to try harder, thickened our plot by lending it subtext. I’m not the beautiful friend; that’s not my category. In the schema of how I understand myself, it’s simply not my place. The hierarchy of beauty parcels out different experiences of femininity. Mine mattered, and had grown on me, or perhaps I had grown around it.

And we reach a point where we can talk about it. Not our own looks, which we always discussed, but the no-man’s-land that always sprawled between them. We thought it was contested, but really it was ours. I broach it carefully, at first, like it will bring her power over me. I broach it more boldly when I realize it brings power to us both. A sense of freedom. K reads the draft of this essay. I act out the fake ID scene and we laugh. It’s different than when we were thirteen, at the beach, and I asked the child we babysat who was prettier, and then I put my face in the water like a Victorian heroine and tried to drown myself, but not very hard. Something has changed. We’re getting older. The breathtaking beauty of a young girl eventually exhales, deflates, we all start looking similar, in a decade or two we’ll fall into some binary of well-kept or not well-kept, and then what’ll matter is money, which fingers crossed I’ll have. But with beauty slowly, imperceptibly, leaving her, am I losing something also?

I might be no great beauty, but I’m no innocent, either: the only thing that feels better than being chosen is being slighted. I knew what I was doing, with that boy, with my classmate, the child we babysat, forcing each to play a test where the right answer, K, would always be wrong, would always shock me, gloriously, painfully, but never surprise me, confirming as it did what I already, irrevocably, knew. The rehearsed and yet devastated response it gives me license to perform. Admit it. There’s a power to melodrama; it’s why they call it drama queen. I have a stunning friend who applies lotion to her stunning body, religiously, every night, from her clavicle to her small Egyptian toes, and perhaps this is my version of that. A confused self-caress, interspersed with slaps, which smarts, yes, but says: this is my body, I am here, give me a story, send pathos in my direction, eye rolls allowed.

We play these scenes over and over again like dirges. When Nino picks Lila over Lenù in the second book of the Neapolitan quartet, the sky falls in our stomachs. Yet why does it feel so good? Who can explain our anticipation of that, our desire to see it exercised, exorcised? I’m trying. The night that Lenù learns that Lila and Nino have kissed, she uses “poems and novels as tranquilizers” to subdue her grief. She crafts a narrative, a “frame of unattainability” in which her bitterness becomes “utterable.” Isn’t that what, by reading, we are doing? Isn’t that why I stay less pretty than K? For the sake of extra practice. Practice at making, as we all must, a bearable poetry, a livable story, with characters and twists, of that which would otherwise kill us.

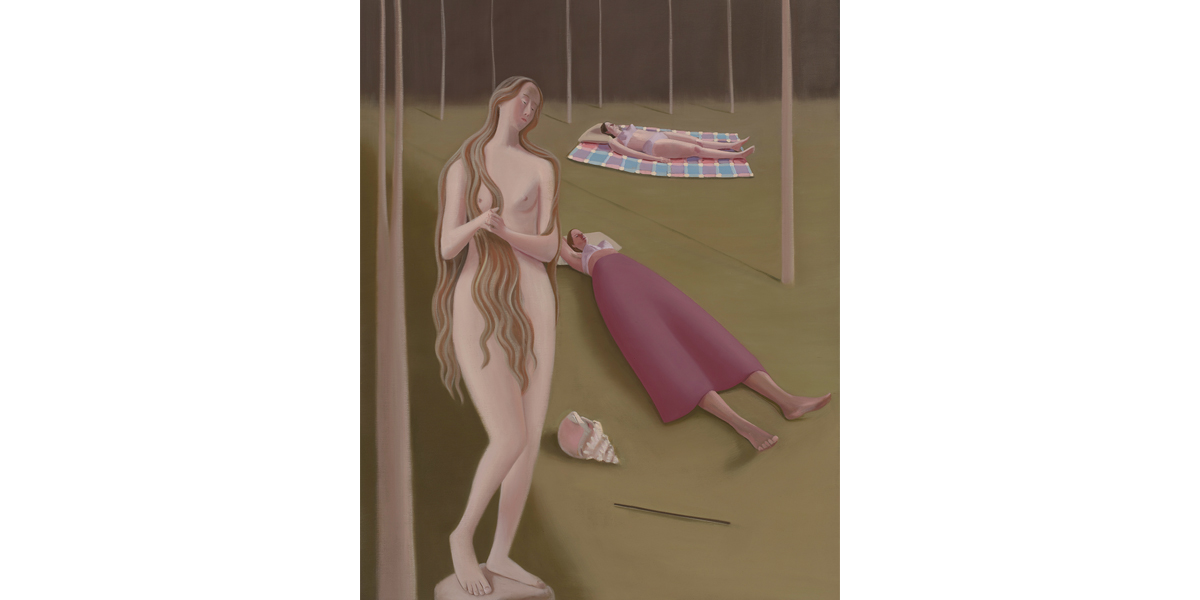

Art credit: (1) Prudence Flint, The Promise, oil on linen, 135 × 107 cm, 2021; (2) Second Hang, oil on linen, 142 × 109 cm, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and mother’s tankstation Dublin | London.

Toward the end of my teens, it began to dawn on me that my face was probably fully formed. That no radical change was forthcoming. That even back when I still held out hope, my features were meanwhile settling, treacherous, into a mediocrity which surprised, humiliated, crushed me. In other words, I was not going to be any great beauty. I was only going to be what I was: attractive occasionally, like most people, relative to whoever happened to stand nearby. I was horrified; I couldn’t get over it. Being average-looking is, by definition, completely normal. Why hadn’t anyone prepared me for it?

I could not have discovered I was plain without discovering K was pretty. She is my friend of many years. Back then, it obsesses me: how we make each other exist. We attend elementary school together, then high school. She enrolls at a nearby college. Her tall grants me my short; my plump her skinny; her leonine features my pedestrian ones. I resent her as much as I exult in her company. In between us, and without words for it, the female universe dilates, a continuum whose comparative alchemy seems designed to confront me, make me suffer, lift her up. Her protagonism diminishes me, or does it? I confuse myself for a long time thinking I am the planet, and K is the sun. It takes me a long time to forgive her.

Comparison steals my joy, but it also gives me a narrative. All in all, it feels radical to make a world together, she and I, a silent tournament of first kisses, compliments, report cards. I live at a fixed point from K, her lucky arms, her lucky neck, her lucky elbows. I pursue beautiful friends like some women do men who will strike them in bed at night. On account of our addictive relativity. On account of my envy, which I’ve made, like many women, the secret passion of my life.

●

There’s something gorgeously petty about many women’s lives. They’re not trying to be great. They’re trying to be better. It’s why women diet together; dye their hair light, then dark, then light again; dress for each other; race to get engaged; wait to get divorced; find a taken man more attractive than a free one. Become girlbosses in droves and then give it up. A woman can spend her whole life in real or imagined competition with her friends, finding herself in the gaps between them. Especially in the game of looks, there is no excellence that is not another woman’s inadequacy, no abundance that does not mean lack. A great beauty is discovered, like crude oil, or gold. That means in a parched desert, or a dirty riverbed, where the rest of us must languish. Our democratic sensibility commands us to raze all unfairness. Yet the way we sacralize beauty, our treatment of the women who try to level it, our satisfaction when no one can, calls our bluff.

For me, the humiliations stack up. I nurse them like little children. I pick at them like scabs. The horrid boy I desperately love, who pretends to love me, studying K’s legs on the trampoline. We are seventeen, and I study them too. Up and down, slender, hairless, vanishing up the thighs, into the sun. Later he sends her a message on Facebook. She does nothing to betray me. What I want is for those legs and the mat of the trampoline to go rigid, to snap, for her bones to spray and splinter, to pierce me through the eyes, so I cannot look at either of us anymore.

Or, a couple years later, when I believe I’ve matured, gotten over it, displaying my fake ID at a college party. It’s my friend’s, I explain. It’s K’s. How funny. It works, we look just enough alike. A drunken classmate laughs. “Yes,” he says. “Except she’s hotter than you.” My face silences him, then the room. His words spread my legs, pass a hand through me, find something dying. He apologizes until I console him. I return to my dorm and drown in abjection, almost pleasurably at this point. I’d like to call my mother, whom I resemble. Except that in all of our talks of puberty, she omitted this. She gave me my face and felt guilty; I had to learn for myself how my suffering held something up.

My own inglorious adolescence ends with me dumped, over brunch, at twenty. He has a strong jaw which dazes and a soft birthmark, near the mouth. He is ten years older than me. That last bit is not the part that hurts. It’s that he’s telling me about another girl. “She’s amazing,” he says. “I haven’t felt like this in a long time.” I think of what we’ve done for a long time and I go to the bathroom and vomit. When I come back he’s still speaking. I wonder, in silence, what it would be like to be the sort of girl about whom they say, he can’t shut up about her. “She’s a writer,” he tells me, with love in his eyes. He looks so handsome, I want to kiss him, exactly now, when, because, he can’t shut up about her. I go home, look her up, write a poem, get over him as soon as I get it published, thinking vaguely, see, there, that was easy, take that—I might be less lovely, but there are other competitions, I can be a writer too.

●

In those bad years I read and reread a story by Émile Zola called “Rentafoil.” A satire, it tells of a wicked entrepreneur, Durandeau, who cooks up a nasty scheme of renting out ugly women as living foils for better-looking ones. Strolling around nineteenth-century Paris, observing “two girls tripping along,” one pretty and one ugly, Durandeau realizes that the ugly woman is an “adornment worn” by her prettier companion. She makes her look good. Her asymmetry sets off her symmetry; her dull face, her shining one. For five francs an hour, Durandeau’s agency makes available to the “upper crust” ugly women to drag about town. There’s nothing like the “pleasure of a pretty woman leaning on the arm of an ugly one,” knowing herself enhanced. And nothing like the sorrow of their Foils, who “fret and fume and sob” at night. Finally, the narrator confesses that he “may write the Secret Memoirs of a Foil,” inspired by one “terribly jealous” employee, lovesick and bitter, who reads too much. “Can you imagine her resentment?” the narrator asks. I could.

But take the first plain girl that inspires Durandeau. She isn’t employed or receiving a salary, but she must be getting something. Or else why on earth would she tolerate it? The unfairness of beauty, the pinch of being its friend. The comforting fable says: the great beauty hurts us like a splinter but helps us like a measuring stick to understand ourselves. Affords us insight, depth. An opportunity to compensate. After all, it’s the plain woman about whom the narrator of “Rentafoil” wants to write, not the beautiful one. I study that poem by Yeats. Waxing about “Two girls in silk kimonos, both / Beautiful, one a gazelle.” How casual, I think. How vicious. If she read that, the girl who wasn’t a gazelle, she probably never recovered. It strikes me only later that she might not have wanted to. For what we tolerate of beauty—that pinch—is also, curiously, what we reap from it.

From Austen to Ferrante, women’s literature is ripe with dyads of women, made up of a beautiful half and a less beautiful half. Here, the arbitrariness of beauty plays out in long, anguished plots, games of chutes and ladders, whereby some women find themselves socially, magically, economically mobile, and others do not, at least not so easily. We recognize the “winner” as soon as we read what she looks like. In first-person stories, more often than not, it’s not the narrator. These plain heroines yearn for, resent, are fascinated by, love, hate, cannot stay away from, their more beautiful, fortunate counterparts. They articulate a precisely feminine pain I know well, worse than menstrual cramps. A sense of one’s own plainness. Inferiority. An envy so profound and wistful it is almost sexually charged.

This tone in women’s literature, this snake twist of the belly that signals envy in the same place as desire, engrosses me. Some of the most exquisite passages of eroticism are in the voice of women envious of other women. Wanting them? Sometimes. Wanting to be them? Naturally. I watch K do the dishes, in her bikini top and her peasant skirt, and the tight abdomen that is an insult, and the overhead light that haloes her hair, careless, the soap, the suds, the satisfaction she must feel. In that moment, I want to take the dishcloth and wipe my face from the face of the earth.

●

I read, at first, in search of consolation prizes.

In the Neapolitan quartet, Elena Ferrante shows how unfairness, like money, accumulates; beauty forms the mask of what crushes, monopolizes, outshines. Lenù, the narrator, is a dogged teacher’s pet, born into poverty, who becomes a successful feminist writer mainly thanks to her diligence. Lila, her best friend, is a wünderkind. Along with “virtuosity” and the power to invent, Lila gets “an odor of wildness” and an “energy that dazed” men, “like the swelling sound of beauty arriving” to Naples. Lenù gets pimples and glasses. Some sirocco wind is always at Lila’s back, making her wealthy; making her loved; making her angry, brave, righteous; almost a model, or perhaps an actress, except she is married so young; the hero, the innovator, the victim, the star.

My insistence on fairness nearly convinces me that, in losing, Lenù must be winning something else. After all, what she envies of Lila is exactly what Lila, in turn, provides her with: content. That’s why Lenù sticks around. When a woman resembles a movie star, her conditions of living take cinematic turns. Life occurs to her quickly, impossibly, like the montage of romance, while the plainer girl plods along, a subject better suited to a documentary. But Lila’s shimmering existence seeps into Lenù’s. The “daily exercise” of noting the “convergences and divergences” between them, the “lines between moments and events” and those deus ex machinas which evade one and land on the other. Envy makes Lenù observant, a student of contrast. Which is to say a better writer—good thing, since we all write ourselves. While everyone plays the main character of their own lives, the plain girl is forced to be a little more thoughtful. She’d be written by Woolf, not Hemingway.

Doesn’t being graceful just mean not having to think? Nothing is laborious, everything is effortless, every morning Christmas morning since puberty left so many gifts. The awkward plain girl is driven, instead, to self-obsession. To make a craft of her posture, her eating habits, her odor, her laugh, why they fail her, how to improve them, the variations that make them superior and winsome in that favored someone else. The symbol of being a plain girl is a heart trying hard. Erasing, scribbling. Romanticizing her contours. Narrativizing her lack.

This is the bone Ferrante throws the plain girls, only to toss it out. Lenù becomes the writer, sure, but even what shines in her writing, we are given to understand, derives from Lila’s unpublished work, effortless, with a “force of seduction” Lenù can only contain, transmit, emulate, as if tracing the path of a comet with her stubby pencil. Whatever prompt for reflection or observation Lenù extracts from Lila, Lila extracts from Lenù too. In other words, don’t kid yourself, even Lenù’s silver lining lies in Lila’s shadow.

Perhaps the plight of the plain girl is redeemed by its realism. Women age terribly. The homely woman gets there first. Everyone knows the genetically blessed woman remains better insulated, to some degree, from humiliation, male disdain, poverty. That Joan Didion thought the streetlights would turn green for her strikes one as rather unhinged, until one sees her photograph, and knows it with certainty. Beauty opens like a trapdoor, to second chances, the benefit of the doubt, a job you’re unqualified for, someone who will marry you, if you so require. The cost may be a life out of touch. The plain woman operates under fewer illusions, always a little closer to the truth. In Wives and Daughters, Elizabeth Gaskell’s last, unfinished Victorian novel, provincial Molly finds herself the stepsister of worldly Cynthia, whose “beautiful, tall, swaying figure” brews predictable scandal and then sidesteps it, at Molly’s cost. For Cynthia wears “her armor of magic”—they all do, letting her slip, eellike, out of the usual scrapes, if only to then get into others. The unfortunate and nameless protagonist of Marguerite Duras’s The Lover, fifteen, compares herself to her classmate, Hélène Lagonelle. Hélène is a virgin, her body “the most beautiful of all the things given by God.” One feels, as one reads, the monsoon brewing. Hélène is “infinitely more marriageable,” but “doesn’t know” what the girl with no name does, of typical survival. Of course not. We’ve read what she looks like. Such knowledge might be worth the price of plainness, if only it didn’t require knowing women like Hélène. “She makes you want to kill her,” the girl confesses.

And what of that final possible solace: that beauty is attended by its own kind of suffering. Objectification. Underestimation. Abuse. Too many men and their egos. Even more seductive an idea: Do beauty’s higher highs mean lower lows? Does whatever miracle that plucks a beauty from the crowd set her up, too, for catastrophe? Crowns her a princess just to cut off her head? Look at Lila in the Neapolitan quartet; she might get special treatment, but she also gets beaten. She loses a child; her anguish is as sharp as her fine bones. Plain Lenù studies, applies herself to an uphill climb, a subdued figure against a headwind, yes, but she does end up, on the whole, better off.

Yet whatever delusional peace this line of inquiry brings us, Ferrante snatches back. No suffering of Lila’s stops Lenù from being jealous of her. “What more do you want?” Lenù asks Lila, bitterly. But what more does Lenù want of Lila? The answer is as simple and complicated, as shallow and treacherously deep, as: Lila’s face, Lila’s body. The Neapolitan quartet undercuts that old, soothing sentence, that compulsive effort to compensate, to equalize, one that my own brother noted I used spitefully in high school, whenever he mentioned a pretty girl: “Yes, she’s beautiful, but…” But nothing. We might identify with Lenù, but who reads Ferrante’s books and wants to be anyone but Lila? It’s not all good, it’s just everything.

●

I fly from Marrakech to London. I wait in line at the airport as a young man is berating a young woman, who begins to cry. I board and discover that by some hellish providence, the woman is sitting next to me. I’m looking good these days, perhaps because I’m finally well-loved, but that’s for another story. The girl tells me everything. She lists atrocities but saves, in a quiet voice, the worst for last. “He said I was average-looking.” I can hardly stand to meet her eyes. The boy is a few rows behind us, chatting up a pretty stranger. “You’re not,” I say. “It doesn’t matter.” I touch her back. Something is happening between us, very wonderful and sad. Then in the middle of her sobs she holds her hands up, and laughs a little. “I’m sorry,” she says, and then crying harder, her voice breaking: “It’s just your hair. It looks so… beautiful. It seems so… soft.” It’s hurting her. I put it up.

In the first of the Neapolitan novels, Ferrante places a wealthy, “superior” girl in green—green shoes, green jacket, green bowler hat—green, the color of envy, in Lenù and Lila’s path. By the second book Lila remains worried over her. “You’re much prettier than the girl in green,” Lenù consoles her, then thinks, “It’s not true, I’m lying.”

●

Some evenings I watch the reality TV show Love Is Blind, where the hierarchy of beauty I resent is toppled, then reasserted, to my masochistic schadenfreude. Singles date without laying eyes on each other, only meeting after becoming engaged. No one fares worse in the program than the unattractive woman paired with the better-looking man. Consider her fate as I do, on the couch, over ice cream. Alone, she meets her new fiancé. He kisses, compliments, gropes her, perhaps sincerely. She’s gorgeous, he says. She isn’t. We eye him as suspiciously as she is beside herself with joy. Days later, at a pool party, the couples reconvene. He sees the other women for the first time, and beside them, her, the one he chose, at last in context. His face falls. It is precisely at this moment he ceases to love her.

Other evenings I switch on I Am Georgina, on Netflix. It infuriates me, her story, the whole premise, Georgina Rodríguez, the surprising partner of football superstar Cristiano Ronaldo. How, like millions of other women, she once worked in a shop, playing nice with her customers, despising her days. How, unlike millions of other women, there existed something in her face so naturally beautiful as to unnerve Ronaldo, to stop him in his tracks when shopping, to impel him to take an interest in her. To move her into his mansions, where she might live in luxury, taking care of his mysterious, surrogate-born children, accruing Instagram followers, purses, a reality show, the guiltless blessings of the born lucky. She goes to work by bus. She leaves by Bugatti, forever. It riles me up. I turn on the television and I watch her and watch her until I love her and hate her, as I might a friend.

●

At the first faint signs of aging, relentless K is swift to get work done. Botox. It rankles me. We’re 26 now; isn’t she tired? Energy is neither created nor destroyed, so I search my forehead for her wrinkles and find them. I visit her dermatologist, taking the long way, dragging my feet, vain enough to have booked the appointment but not so vain I would have gone unprompted. The doctor prescribes me: one syringe of filler, to raise me from one level to another, as she did my friend. I infer: two syringes, to close our gap, make us level. An old wish. I nod, close my eyes, grip the table. Beauty, incoming. She readies the needle, then the first injection site. My eyes sting, I think, at the scent of the alcohol pad. Then some misgiving in my face stops her. “You know,” she says, slowly, “You and K are not the same, you are different types of… attractive, you don’t need to rush this.” Implicitly: I’m not as pretty. I have no such pressure, to prejuvenate, or invest. I sit up. The insult frees me. I could almost kiss her. I float to my car and drive home dancing, catching my flaws in the rearview mirror, like darlings an editor didn’t make me cut.

I’d gone to finally compete with K but settled for comparison, that poignant force that had always pushed me, turned my page, compelled me to try harder, thickened our plot by lending it subtext. I’m not the beautiful friend; that’s not my category. In the schema of how I understand myself, it’s simply not my place. The hierarchy of beauty parcels out different experiences of femininity. Mine mattered, and had grown on me, or perhaps I had grown around it.

And we reach a point where we can talk about it. Not our own looks, which we always discussed, but the no-man’s-land that always sprawled between them. We thought it was contested, but really it was ours. I broach it carefully, at first, like it will bring her power over me. I broach it more boldly when I realize it brings power to us both. A sense of freedom. K reads the draft of this essay. I act out the fake ID scene and we laugh. It’s different than when we were thirteen, at the beach, and I asked the child we babysat who was prettier, and then I put my face in the water like a Victorian heroine and tried to drown myself, but not very hard. Something has changed. We’re getting older. The breathtaking beauty of a young girl eventually exhales, deflates, we all start looking similar, in a decade or two we’ll fall into some binary of well-kept or not well-kept, and then what’ll matter is money, which fingers crossed I’ll have. But with beauty slowly, imperceptibly, leaving her, am I losing something also?

I might be no great beauty, but I’m no innocent, either: the only thing that feels better than being chosen is being slighted. I knew what I was doing, with that boy, with my classmate, the child we babysat, forcing each to play a test where the right answer, K, would always be wrong, would always shock me, gloriously, painfully, but never surprise me, confirming as it did what I already, irrevocably, knew. The rehearsed and yet devastated response it gives me license to perform. Admit it. There’s a power to melodrama; it’s why they call it drama queen. I have a stunning friend who applies lotion to her stunning body, religiously, every night, from her clavicle to her small Egyptian toes, and perhaps this is my version of that. A confused self-caress, interspersed with slaps, which smarts, yes, but says: this is my body, I am here, give me a story, send pathos in my direction, eye rolls allowed.

We play these scenes over and over again like dirges. When Nino picks Lila over Lenù in the second book of the Neapolitan quartet, the sky falls in our stomachs. Yet why does it feel so good? Who can explain our anticipation of that, our desire to see it exercised, exorcised? I’m trying. The night that Lenù learns that Lila and Nino have kissed, she uses “poems and novels as tranquilizers” to subdue her grief. She crafts a narrative, a “frame of unattainability” in which her bitterness becomes “utterable.” Isn’t that what, by reading, we are doing? Isn’t that why I stay less pretty than K? For the sake of extra practice. Practice at making, as we all must, a bearable poetry, a livable story, with characters and twists, of that which would otherwise kill us.

Art credit: (1) Prudence Flint, The Promise, oil on linen, 135 × 107 cm, 2021; (2) Second Hang, oil on linen, 142 × 109 cm, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and mother’s tankstation Dublin | London.

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.