A few days after my youngest brother died last August, I started to think about Lazarus all the time. Not a surprising turn of the mind, given the years I spent in Protestant Sunday schools where miracle stories are dispensed before the Goldfish crackers and Dixie cups of juice. The raising of Lazarus appears only in the Gospel of John, just 44 brief verses. Lazarus of Bethany was a friend of Jesus’s and brother to Mary and Martha. When Lazarus gets sick, his sisters send for Jesus, saying, “Lord, he whom you love is ill.” Love or not, Jesus does not fly to Lazarus’s side. He tarries two more days, after telling his disciples that the “illness is not unto death; it is for the glory of God, so that the Son of God may be glorified by means of it.” When they do arrive, Lazarus is dead. “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died,” first Martha and then Mary say. As Jesus weeps, the onlookers exclaim, “See how he loved him!” Some also murmur, understandably, “Could not he who opened the eyes of the blind man have kept this man from dying?” When Jesus orders the stone that seals the tomb removed, Martha objects that there will be an odor “for he has been dead four days.” (In the King James Version, this is rendered as “by this time he stinketh.”) Nonetheless, the tomb is opened. Then Jesus cries, “Lazarus, come out,” and “the dead man” does, despite the adjective that strands him in paradox. He wears the trappings of death: his body is wrapped in grave clothes, his feet tied, his face covered with a cloth. As if releasing a prisoner, Jesus commands, “Unbind him, and let him go.” Presumably, they do. But what then? What was his second life?

In church, I learned this story as a kind of literalized metaphor. Jesus did raise the dead, but the raising was a means to an end, just as he said: a demonstration of godhood through the reversal of the irreversible. In fact, I was told, Jesus deliberately waited until Lazarus had been dead long enough for decomposition to begin, so that the miracle would be all the more glorious. Lazarus’s resurrection also triggers the next phase of the gospel plot: it agitates the religious establishment, who worry that Jesus will accrue more and more followers, which could lead to violent suppression by the Roman authorities. Thus begins the conspiracy to kill him. Lazarus is a proof of divine identity, a link in the chain of events organized by God and carried out (unwittingly) by humans, and a dress rehearsal for the greater death and resurrection soon to come. What he isn’t, here, is a man. A man who dies twice. A man with two sisters.

“Sister of the dead man,” Martha is called. I, one of six sisters of the dead man, read and reread John 11 as if it were a novel redacted by a heavy-handed censor. I feel the desperation of the women who send that guilt trip of a phrase, “he whom you love,” not “he whom we love.” Had you been here, they repeat, he would not have died, an avowal of faith that I hear in a tone of fierce reproach. They believe so hard that the loss hurts worse. And the stench of the tomb? Martha is not protecting the others from a noxious odor; she is shielding herself and her sister from sensory confirmation of their brother’s death. This is all heretical. And, stupid as it may be, I have begun to cry as I write this.

As far as I know, Lazarus’s age at his first death is never revealed. My brother was 22, and he died not by illness but by another man’s hand. For practical reasons—autopsy, coroner’s report—seventeen days passed between the day he died and the day I saw his body. He had been embalmed, so he didn’t stink. Someone had shaved his face. I heard a guttural moan, and, to comfort my mother, I reached for her to find her reaching for me. It was my mouth making that sound, my body pitching forward to cover my brother’s, as if I would climb into the casket with him. I pressed my face against his smooth jaw. It’s both event and duration, dying—at least for the living—and the event repeats even as the duration holds. He is dead; no, he is not dead.

He is dead. Death, as many have noted, creates grammatical problems. What Roland Barthes names the “utterly unadjectival” state is pinned by an adjective. Lydia Davis puts the conundrums of tense typically succinctly: “When he is dead, everything to do with him will be in the past tense. Or rather, the sentence ‘He is dead’ will be in the present tense, and also questions such as ‘Where are they taking him?’ or ‘Where is he now?’” There is also the trouble of subject: to whom does “he” or “him” refer? The person it used to denote does not exist, or does not exist in the same form. But something stays—if not him, then what I called his body or, more reluctantly, his corpse. If such usage can be correct, Davis adds, then “for how long”? The body that comes forth from the tomb presents similar problems. If this, too, is his, is it the same?

Artists cannot resist the drama of the miraculous body. Giotto paints a white-faced figure swathed in white, a Lazarus bound so tightly that I imagine him hopping out like a child in a sack race. Sebastiano del Piombo renders a tumult of color in which a pink-clad Jesus lifts one hand toward heaven and extends the other toward a muscular Lazarus who strips a cloth from one arm while looking up at Jesus, the way you might undress before sex, urgently focused on another. I prefer Caravaggio’s. The likely apocryphal story is that Caravaggio modeled his Lazarus on the exhumed corpse of a recently deceased man. Lazarus, naked—convenient shadows and a man’s arm conceal his genitals—and sprawled diagonally across the painting’s center, does have that rigid languor peculiar to the dead. His eyes are closed. This resurrection, like Giotto’s, is not instantaneous. Most of the crowd stares at Jesus, who stands tall in the left foreground, pointing beyond Lazarus—to the empty grave? But Lazarus’s sisters, on the far right, bend over their brother. The nearer sister cradles his head. Her face is so close to his that she might be grazing his cheek with her own, it’s hard to tell. Their noses almost touch, like she’s trying to breathe his breath or smell his living scent. Here I find a shred of what I searched for in the biblical text: human love, powerless yet frantically active. One of this grief’s many paradoxes was that I felt as if I were capable of more than ever before in my life: nothing could frighten me except, as in D. W. Winnicott’s formulation, the catastrophe that has already happened. My love felt strong enough to produce anything, though it couldn’t. The force of my weakness surged through me.

I wasn’t alone in this. In the Iliad, Priam’s recovery of Hector’s body is a triumph of vulnerability over pride and power: “I have kissed the hand of the man who killed my son.” Gilgamesh violently laments over Enkidu’s corpse until maggots creep out of his nose, and then embarks on a futile quest for immortality. Many of Ovid’s metamorphoses occur in the extremity of grief as an excess of energy transforms the world, if not in the way the grieving wish: Phaethon’s sisters slowly harden and leaf into poplars at his grave; the stone Niobe weeps for her children; Hecuba, enraged about the murder of her son, morphs into a literal bitch, snapping and biting forever. Orpheus, pleading “for a loan,” makes “the bloodless shades weep.” Demeter lays waste to the earth. Something must change. In such moments, it is not hard to believe that you could resurrect one person, if you could find the right words or the right path to the underworld—and, crucially, out again. The problem seems one of method, not power. This essay is the fruit of a necromantic passion, and an emblem of failure. I remain sister to a dead man.

●

What counts as resurrection? A general rising of the dead, a return from the afterworld at the end of time in some physical embodiment, is specific to a small group of monotheistic religions: Zoroastrianism, Islam, Judaism, Christianity. Irksome sympathizers say that the dead person will “live” in memory. Reincarnation, especially prevalent in the belief systems collected under Hinduism, is an expansive view of resurrection. The “undead”—whether zombies or ghosts—cluster at the threshold of living again. Science fiction and the superrich try to upload the self to a mechanical container. Some physicists propose the eventuality of a quantum resurrection out there in this universe or another. The corpse fertilizes the cemetery grass. What I began seeking, though, was a straight-up rewinding, my own Lazarus, selfsame.

But even Lazarus’s resurrection, a case of supercharged healing, faces the problem of change. Although Lazarus aged like an ordinary man, he supposedly never smiled again. This might seem a surprising legend for Christianity, which made one particular resurrection the core of its salvific promise—but it is exactly the centripetal force exerted by resurrection that compels Christianity to struggle with the resurrected person, who must also have a resurrected body. (Christian personhood, attempting to overcome Hellenic body/soul dualism, embraced psychosomatic unity.) The conundrums that ensue are obvious even to children. When we were no more than five or six, after our mother turned off the lights, my sister and I used to discuss perplexities, including resurrection: Which of the bodies we have in life would rise again? What if we died before or after we had the ideal body, which would be, we agreed, old but not too old—say, sixteen? Would this body have all the same parts? Would it eat and excrete? Only many years later did I realize that some of the most famous Christian theologians have debated these exact questions.

The seed, the foundational Christian metaphor for the resurrected body, first appears in 1 Corinthians: “What you sow does not come to life unless it dies. And what you sow is not the body which is to be, but a bare kernel … So is it with the resurrection of the dead.” As with many biblical answers, even an ardent believer is likely left with more questions. Despite its Pauline source, the seed metaphor, which implies a transformation, did not go unchallenged as a paradigm. For hundreds of years, theologians advanced competing metaphors, from the body as river to resurrection as fish puking up drowned corpses. Would bodily resurrection entail some transformation, as in the seed or the river, or would it be a reassemblage of the material entirety, as in the vomiting fish or, less graphically, a statue melted down then reconstructed? The tension, at a deeper level, is a conflict between a body that continues to change, even after death, and a body fixed forever in stasis. This dilemma preoccupied Christians for many reasons, theological and not, but the tension also speaks to our refusal of the metamorphosis wrought by death and our simultaneous inability to push it aside.

“Pearl,” a Middle English poem attributed to the anonymous Gawain poet, portrays a vision in which a father encounters the daughter who died, his soul swept into some land adjacent to paradise. She died as a young child, but when he meets her again, her body is a grown woman’s. At first, he fails to recognize her, and the slow dawning is dramatized through a detailed description of her beautiful new form. They converse at cross-purposes, she having all the heartlessness of heaven and he, overcome with “love-longing,” filled with earthly misunderstanding, always looking back. He may even wish for the little girl he buried. Rereading “Pearl” recently, I wondered if the poet had had a daughter who died. It would surprise me, despite the intensely realistic portrait of a grieving father. Corpse poems—a lyric resurrection—ventriloquize the generic dead, the historic dead, the mythical dead, but only rarely the beloved dead. Despite my own love-longing, this makes sense: writing in my brother’s voice would violate the self he used to have and its very absence.

The same is true for imagining who he might be in a second life. Some attribute Lazarus’s dourness to having witnessed the underworld’s bleak state, but a more interesting explanation emerges in one of Robert Browning’s weirder persona poems, in which a skeptical physician examines a man who believes he has died and been brought back to life. The man—Lazarus, we quickly understand—is physically sound but utterly indifferent, even to the illness of his own child. For him, the “thread of life… / runs across some vast distracting orb / Of glory on either side that meagre thread, / Which, conscious of, he must not enter yet.” The knowledge gained by dying itself has de-formed Lazarus for living, left him stupefied and unsmiling.

●

The journey to and from the afterworld is invariably marked by difficulty—and, often, by some pivotal failure. It strikes me as a tragic fracture in the voluminous human imagination that even in myth and stories unpressured by fact, even in a faith rife with improbabilities, human resurrection can be a miracle, a perforation of the ordinary, but it can almost never be a fantasy fulfilled. Or perhaps it is less a fault than a choice: maybe we are choosing the pain of reality. Like waking from a pretty dream you know is a dream, like staring at your brother’s dead face. To be represented, the resurrection must be imperfect, a painting slashed by its painter right at the moment of completion.

After his wife died, Czesław Miłosz wrote a version of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth. His poem makes Orpheus’s failure an intrinsic consequence of his humanity, not an avoidable error. As he travels up, up, he hears—he thinks—the tap-tap of Eurydice’s feet behind. When he pauses, the footsteps halt; when he continues, they do too. Are these steps an echo or another person? “Under his faith a doubt sprang up,” a doubt whose only source is himself: he’s been given clear instructions, and he could just as easily interpret the footsteps as evidence of her perfect following, patiently pausing whenever he does. But, though he does keep walking without glancing back, he has already started to mourn the loss “of the human hope for the resurrection of the dead.” Both the hope and its failure to convince are human impulses, and even Orpheus could not sustain a belief in his own success. When he turns, everything is “as he expected … behind him on the path was no one.” None of Ovid’s outstretched arms and whirling winds. Eurydice’s long gone. Whether she was ever there at all is beside the point. Orpheus’s mind, not his movement, kept her dead.

If I, like Orpheus, had the method, would I, too, lack the power? I have to say yes, though I hate myself for it. The doubt springs up, about where they are and, worse, who they are, if they are. Likening Lazarus’s resurrection to a healing was a mistake: death isn’t the uttermost sickness—it is, in Barthes’ words, “the void of love’s relation.” This “void” is not just something going missing. When love’s everyday exchange becomes a one-way energy, all interplay breaks off. What remains is the Orphic journey, moving forward suspecting that any footsteps behind are merely echoes of your own. The drive to resurrect is born of love, but the resurrection itself cannot be born of love’s relation. Although Lazarus may have clumsily shuffled into the light on his own, first he had to be called. It is almost too painful to admit this, but that change we can neither abide nor ignore does force the question: Would he want to come back?

●

Recently, I dreamed that I was telling a story to my brother, who was three or four. We were sitting on the green-carpeted floor of a house that no longer exists. He wore red shorts, no shirt. His skin was deeply tanned, as always in summer. He kept glancing through the windows at the bright afternoon. I couldn’t hear my own voice; the story was silence to me. Then I realized I was dreaming, and that he was not present beyond the dream. I needed to hold him there. Despite his curiosity about outside’s pleasures, he would keep listening as long as I kept the tale going. So I talked and talked, still silent to myself. I felt fear—that I would run out of words—and a wonder that billowed like the gauzy curtains in the breeze. This is the best story I will ever tell, I thought, and I wished, even more upon waking, that I could hear this, my masterpiece.

That I kept talking seems an obvious sign of the overwhelming desire to communicate. That I could not hear my own voice suggests that, even asleep, my mind enforces the impossibility of communicating. What could I say, after all, that would reach him where he is now? Nonetheless, the dream dynamic remains the waking one. The Barbadian poet Kamau Brathwaite wrote a collection of poems addressed to the various dead entitled Elegguas, a play on “elegy” and Eleggua, the orisha of paths, thresholds and crossroads. In one poem, Brathwaite informs a beloved that others say she can’t come back: “as / if you cross some Great Divine Div- / ide or Water and you of all people / my love are now some Something / Dangerous & Other—some somethin / (g) Different & Alien & even Ugly. / Can you imagine how this make me feel?”

“As / if,” he says. The little phrase, broken by the line, captures all that disbelieving sorrow. “As if” is the beginning of the path to the dead. It is as if you are gone, so I will try to reach you, though you may be different, though you may not understand how living as if you are gone makes me feel. Goading myself through writing my brother’s eulogy, I felt as if I might die from the effort of expression, and yet people insisted that it was fortunate that I was a writer, not understanding that words could only truly be a consolation if they called him back.

At the climax of Abel Gance’s 1919 film J’accuse, the dead of World War I answer the call of a mysterious voice and rise from the battlefield, ungracefully, like sleepers with tingling limbs. “Diaphanous and fantastically heroic,” they stride away to determine if the living have made their sacrifice worthwhile. The dead soldiers are played by wounded veterans, including the writer Blaise Cendrars, a friend of Gance and Guillaume Apollinaire. Cendrars lost his right arm, first in the war and, he said, “a second time” in the film. Apollinaire, too, was wounded on the battlefield. Weakened by his injury, he died of the flu in 1918, two days before the war ended. Cendrars recounts how Apollinaire’s funeral procession, on its way from church to cemetery, “was besieged by a crowd of noisy celebrants of the Armistice, men and women with arms waving, singing, dancing, kissing, shouting deliriously the famous refrain of the end of the war: No, you don’t have to go, Guillaume / No you don’t have to go…” The eerie synchronicity of the popular song and the private wish reminds me that it is not hope that keeps us calling. Like Cendrars listening to the jubilant masses sing as if to his dead friend, there is nothing else for us to do, though the song will restore nothing, nor reach the ears of the dead man who passes through the chanting crowd. A failed spell, perhaps all speech ends up as direct address to the only one who can’t hear.

In their time, Gance and Cendrars were just two of a host of people talking to the dead—and, further, trying to call the dead back as visions or communicants. World War I was one of the mass-death events that make afterworlds a public preoccupation. Spontaneous psychic phenomena were common; a multitude of soldiers reported seeing their dead fellows on battlefields. Families pressured governments to identify and repatriate bodies buried in foreign land, and the black market in corpse recovery thrived, as frustrated relatives circumvented official channels. With or without a body to bury, many searched for something to fill the void of love’s relation. Spiritualism, both as an organization and a loose set of beliefs, surged during and after the war, as many, especially war victims, actively pursued messages from the dead, often through mediums. The war also led to a rise in unofficial or informal networks of support, material and not. In Paris, poor families living in a housing project, now called the “Cité du Souvenir,” each “adopted” a dead soldier, unrelated to them, and inscribed the names and dates of birth and death above their apartment doors. Such widespread loss from a single source created a different kind of love relation, a variety of social alliances formed by absence.

“Tombs die too,” Roland Barthes wrote in his linguistic monument to his mother, Mourning Diary, and the truth of those words is evident in the way we stroll past memorials to devastation that once vividly insisted on shoving the absence of the dead into the world of the living. In the Cité du Souvenir, where people presumably go about their daily business not thinking much about the adopted dead, a plaque at the entrance proclaims the intention “to honor the dead by an act of life,” and if honoring does happen, it may be in banal movements and an occasional flicker of awareness while hauling in groceries. Barthes believed that a monument must be something in flux: “an act, an action, an activity.” His theory of monuments reminds me of the Mapuche practice of amapüllün, in which the living retell the life stories of the dead at funerals, shaping a whole from the disparate events. The telling helps the dead person to move into the afterworld. The amapüllün seem to differ from Western eulogies because the act matters as much, if not more than, the content of the act. The making of the passage, not the passage made.

As difficult as it is, any communication to the dead must account or allow for some translation from this world to afterworld, in which a transformation of language or its necessity may also occur. An ethnography of Black women who “talk to the dead” in Lowcountry South Carolina shows how diverse “talking” can be: one woman speaks to her mother through songs, another to her sister in dreams, yet another communicates through the weaving of sweetgrass baskets. The dead do not always, or even mostly, reply in words. Maybe it doesn’t matter what story I summoned for my brother; maybe the dream’s true communication lay in his bright child face, suddenly still as he concentrated on what I was saying—or on something within himself that I could witness but not know. I did know that eventually he would leave me. Such exchange, everyday rather than extraordinary (unlike spirit possession), requires a willingness to be with those who are no longer here as they used to be—to, as I have struggled to do so far, release them from the form and voice they had before.

●

In January, my friend Carina and I stayed in a small town in northwest Puerto Rico while she finished her dissertation and I supposedly worked on my novel, but mostly researched resurrection. We both have familial ties to the island (her mother, my father), and we talked regularly about the feeling that arrived at times, strolling around the plaza for entertainment or stepping into the wild green of the mountains, as if we reprised the early lives of our grandmothers. Other times, eating breadfruit for breakfast or lying on a sunny rock by a river, we discussed the sense of embodying something much older, a pattern of life crafted by long-ago people, which it seemed hokey (at least to me) to name “ancestors”—though what else could you call them?

At night, on unsteady internet, I watched short segments of Let Each One Go Where He May, a film composed of thirteen extended tracking shots, in which two brothers follow the route upriver that their ancestors took when escaping from Dutch enslavement to the deep jungle of eastern Suriname. I watched it before sleeping because it was boring, its changes mostly subtle if noticeable at all: a shift in the canopy, different bends in the same wide river. Although the brothers’ boat had a motor, sometimes they rowed, and despite their modern clothes, in those moments I glimpsed the Saramakans three hundred years ago. A journey through space, it was also a journey through time.

The vision of my brother getting up out of his casket shatters again and again. In its place, I have turned to ritual acts, especially ones of embodiment, as the most attainable method of resurrecting him. And more than in the version of Christianity I grew up with, I find inspiration for these acts in the practices of African and indigenous religions, where rituals often entail improvising. A dance with specific steps, yet redefined by every dancer. There’s space for life to intrude, a particular life even—the one I am seeking.

In a beautiful essay on Garifuna rituals, Paul Christopher Johnson describes the dügü, a multiday ceremony in which the ancestral dead become present through their descendants “acting ancestrally, even becoming ancestral, in myriad routine, practical tasks”: they fish in the old way, in boats made the same way; they wear clothes dyed in achiote. Throughout the days of preparation, feasting, singing and dancing, the community acts as they once did. Spirit possession features in the dügü, but it is not the ultimate aim, nor the only mode of ancestral return. The embodiment surpasses mimesis; in the dügü’s space-time a resurrection occurs “through the dogged, selective performance of everyday labor … in the collective performance of this vivid tableau vivant, one with no spectators but the participants themselves.” As incarnations go, it is slow and sometimes tedious. Resurrection as ritual act surrenders the will to reverse time for residence in mythic no-time, and imagines the passageway as moving toward the dead with no intention of dragging them back or demanding they follow you.

For me, the first of these acts was accidental. The evening after my brother’s funeral, my family and a few friends gathered in the center of downtown Columbus, Ohio, at a hillside park on the banks of the Scioto River, to release paper lanterns. We had never done this before, and I can’t remember whose idea it was, or why we chose such a public location for an illegal activity. We wanted, I think, to see the lanterns glow on the surface of the dark river. From the start, everything went awry: the lanterns were hard to get going, and the wind was blowing the wrong direction, away from the river and toward downtown’s office buildings. One lantern, let fly too early, zipped toward a tree, with someone chasing madly after and leaping toward the branches just in time to keep the tree from becoming a torch. “That’s him,” one of my sisters said. And I knew what she meant.

I have been reluctant to name my brother here, afraid of reducing him to a character in my Orphic psychodrama. But it seems appropriate, now, to say that his name is Stephen, a sign that marks his many selves, including the final dazzling one, the potentiality of everything he could have been. He was an anarchic spirit, always mischievous, a troublemaker almost from the moment when he, a few days old, first strained to raise his head. As a baby, he only wanted to be held facing outward, toward the world, which quickly became a family symbol of his way of being. More than anyone I know, he noticed and delighted in the textures of existence. He would have laughed at our disaster of a memorial, and its disastrous execution seemed more fitting than the solemn beauty we’d intended. The last lantern whirled away above a skyscraper. Suddenly my mother said, “I’m going to roll down the hill,” and she did. We watched her come to a stop, laughing and apparently intact, at the bottom. The rest of us followed. Someone shouted: “Watch out for the stump!” Before I rolled down a second time, I paused to survey the hill for obstacles and, looking at these people I love—giddy, sprawled, bruised, flinging themselves into childish activity—I cried through a breathless laughter. These fugitive moments of intimacy with Stephen, as if he has once again approached too quietly for me to notice and surprised me by placing his big hand on my shoulder, feel like minor resurrections. They never stick; they never will.

The rituals accrue more deliberately too. In January, on my birthday, Carina and I drove an hour and a half to Cabo Rojo, an incomplete spiral of land in Puerto Rico’s southwest. I carried a small stone made from my brother’s ashes. I’d brought it from New York to leave somewhere on the island, I hadn’t yet decided where. Though I found myself vaguely ridiculous, I wanted part of him to stay where some of his ancestors were, in whatever form they now took. As we traced the edges of stunning cliffs I asked myself, Here? Here? On a narrow beach covered with stones of all colors, I looked out toward a natural bridge of stone that arches from the cliffside into the sea, and pictured it as a portal to an afterworld, having just seen a Haitian painting of the dead clustered on the other side of a body of water, glimpsed through a similar archway. Nearby, a young woman in a red bikini posed expertly for photos taken by her boyfriend. With her shifting smoothly from one sexy attitude to another, I felt too awkward to place the stone. The clash of my silent attempt at communion with the dead and the future Instagram carousel amused me, because it would have amused Stephen. Then, as if my amusement was his amusement, a different portal opened, keyhole-slim, through which he briefly slipped. In the clear waters of Bahía Sucia I did feel free to release the stone, knowing it would float away, then dissolve.

This summer, in Cyprus, where my brother never went, I repeated my invented ritual. The island’s easternmost point is the skinny Karpaz Peninsula, so remote and empty that you sense the sea on every side. At night, the dream of walking on water seduces. I’d brought another stone along because I wanted some part of him to have traveled with me. The sea is shallow for a long way out. I walked till I could no longer stand and then dove down, stone in my left hand. Before I could embed it in the sand, I lost my grip and though I looked, eyes burning from salt, it was gone.

Toward sunset I walked with a friend to the end of the beach, about half an hour, and then clambered up over rocks and dunes. The sea briefly disappeared from view; the landscape became an alien desert. The crest of the highest dune reveals below another sandy beach, longer and emptier and wilder than the one we left, walled by steep dunes and limestone cliffs so that it’s almost inaccessible except by sea. Stephen would have dared the climb down, heedless of the difficult trip back, and as my friend and I sat silently I believed for a second that I saw him coming toward us, far down the beach. Of course there was no one, and certainly not my brother. With one finger, I idly drew a thick spiral, in the style of Taíno petroglyphs I’d seen in Puerto Rico, in the sand. My friend noted that there was almost no wind, so the spiral might last till morning. We agreed to return and check. But we were tired when we woke, so we swam, and then it was time to leave. In my mind the spiral is there though it is not there.

Barthes again, like Brathwaite living “as if”: “Actually, as a matter of fact, always that: as if I were as one dead.” The most paradisiacal human trait is that we are inevitably surprised by death’s reality, despite its inevitability. The death of someone whom you love is a discovery of Death in the abstract as well as the particular: the appearance of disappearance, not only of the dead person, but of yourself. A quicksand pause: the absence of yourself from time. The sense of being ejected from time’s usual flow is common among the grieving, from my anecdotal polling. A writer who also lost a brother young, and violently, told me that at some point—he did not give a date or duration that must be exceeded—I would “rejoin time,” but, he added, if my experience turned out anything like his, some days, even decades later, would be “that first day after again.” Time, I suspect, will never move as it did before, even after I step back into it.

Being thrown out of time or immured in a fixed point within it is a way of dying with the one who has died, an unwilled and yet welcome journey that brings us nearer to being dead. My brother was shot in the chest three times, and every day I shape a gun out of my hand and press it three times to my chest. This ritual is a way of entering the event that I can never live, though I survive it: his dying, not mine. That I go on living while he does not still surprises me. Yet I now think the living hasn’t been continuous. If I have found any resurrection for sure, it’s mine, not my brother’s: as soon as I said, to another sister, “Stephen is dead,” it was as if I, like Barthes, were one dead—and then I came back to life, changed, like Lazarus always and probably until my final death glancing at that vast distracting orb beyond. This vision of the world coincides with the early Christian belief that they lived in a mythic age presently, an eschaton in which miracles indeed happen, like the raising of the dead. Time in the eschaton cannot be normal time; it stops, it loops, it mixes up states and tenses, it is adjacent to, but not within, eternity.

“Love is most nearly itself / when here and now cease to matter,” T. S. Eliot writes. For me, this is not a call to stasis, the statue rebuilt, but to envision love as perpetual motion, albeit not in one direction—abandoning, thus, the seed, and the river, unless it flows both ways. Maybe better to invoke the sea in which I cast my stones. Dante, famed voyager to afterworlds, fills the Paradiso with images of circular motion. And in the Commedia’s concluding lines, his last sight of heaven is an experience of merging with the cosmic revolutions: “But now my will and my desire, like wheels revolving / with an even motion, were turning with / the Love that moves the sun and all the other stars.” This is a beautiful truth that structures the universe, the culmination of the divine. But I believe this movement is human too, as human as those icky biological processes some early Christian theologians tried to erase: eating, digestion, excretion, the putrefaction of the corpse in the grave.

When Mary Magdalene meets the resurrected Jesus, she looks right at him, but does not recognize him, “supposing him to be a gardener.” Only when he addresses her does she realize who he is. She turns toward him. John does not describe the action, only the dialogue, so it is left to us to imagine what leads Jesus to say, in the Latin that has become metonym for the scene as a whole, Noli me tangere, usually translated as “do not touch me” or “do not hold me.” The noli me tangere encounter is another one artists cannot resist. There are myriad arrangements of Jesus and Mary Magdalene: his hand stretches out in refusal, she kneels, he bends, they both stand, they look at each other, one looks away. Almost always she reaches for him. Sometimes she makes contact. The multitude of portraits reflects the ambiguity of the simple phrase, which opens a range of possible relations. Perhaps he rejects her touch because he cannot bear the shock of intimacy, divided as they are by the fact of the resurrection. Perhaps, even as he speaks, he touches her, to hold her away from him. It’s possible, the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy argues, to translate the phrase as “do not wish to touch me.” If you do, then it becomes an exhortation to love the death too, because it is intrinsic to every life. Meanwhile, Mary’s hands hang in the air. Resurrection is Dante’s eternal rotation, “spurred on by flaming love”: it is the ongoing allegiance to keeping in sight the appearance of disappearance. It is living as if. It is a game of hands, an everlasting reaching after what escapes, what you love.

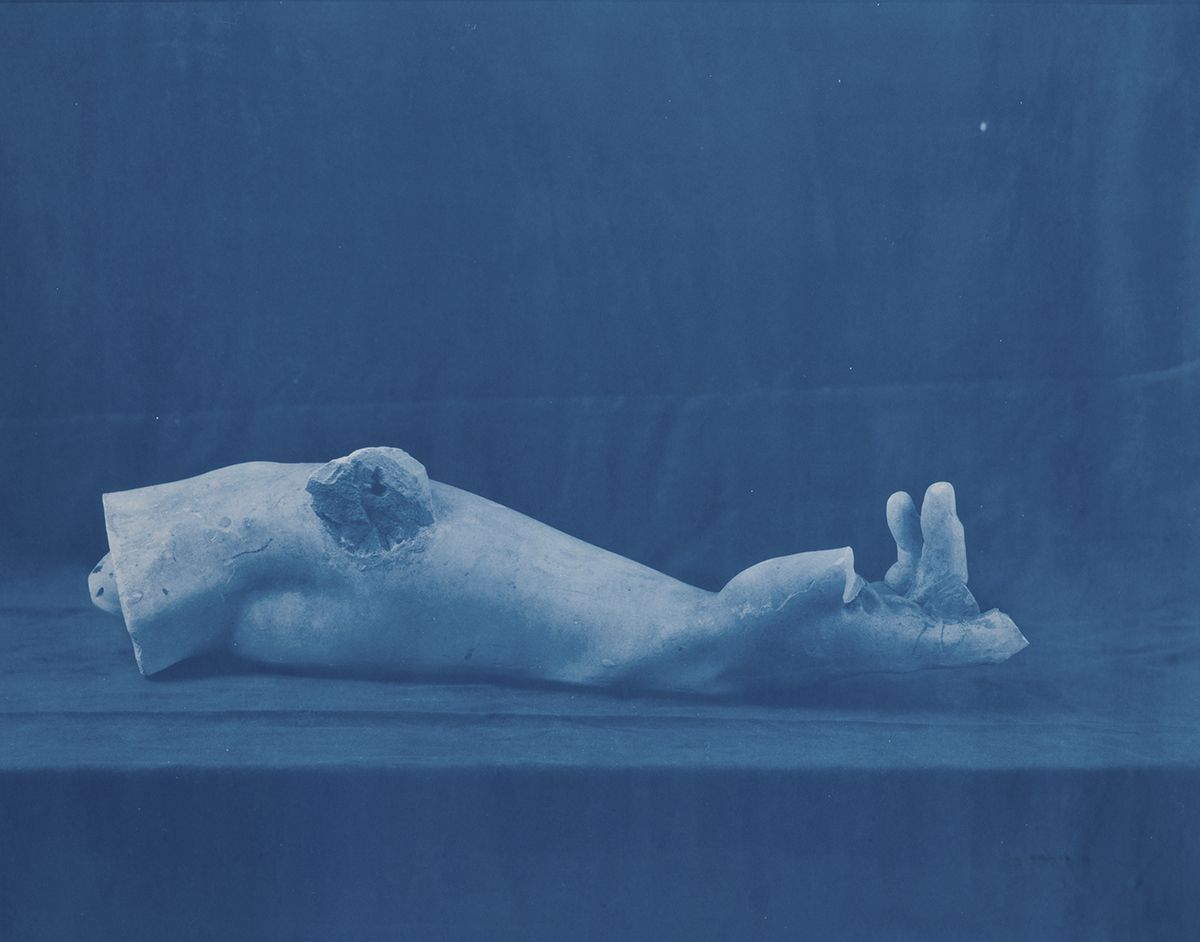

Art credits: Christine Elfman. Amaranth Extraction II (2016), silver gelatin print colored with amaranth dye; Fragment V (2019), cyanotype. All images courtesy of the artist.

A few days after my youngest brother died last August, I started to think about Lazarus all the time. Not a surprising turn of the mind, given the years I spent in Protestant Sunday schools where miracle stories are dispensed before the Goldfish crackers and Dixie cups of juice. The raising of Lazarus appears only in the Gospel of John, just 44 brief verses. Lazarus of Bethany was a friend of Jesus’s and brother to Mary and Martha. When Lazarus gets sick, his sisters send for Jesus, saying, “Lord, he whom you love is ill.” Love or not, Jesus does not fly to Lazarus’s side. He tarries two more days, after telling his disciples that the “illness is not unto death; it is for the glory of God, so that the Son of God may be glorified by means of it.” When they do arrive, Lazarus is dead. “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died,” first Martha and then Mary say. As Jesus weeps, the onlookers exclaim, “See how he loved him!” Some also murmur, understandably, “Could not he who opened the eyes of the blind man have kept this man from dying?” When Jesus orders the stone that seals the tomb removed, Martha objects that there will be an odor “for he has been dead four days.” (In the King James Version, this is rendered as “by this time he stinketh.”) Nonetheless, the tomb is opened. Then Jesus cries, “Lazarus, come out,” and “the dead man” does, despite the adjective that strands him in paradox. He wears the trappings of death: his body is wrapped in grave clothes, his feet tied, his face covered with a cloth. As if releasing a prisoner, Jesus commands, “Unbind him, and let him go.” Presumably, they do. But what then? What was his second life?

In church, I learned this story as a kind of literalized metaphor. Jesus did raise the dead, but the raising was a means to an end, just as he said: a demonstration of godhood through the reversal of the irreversible. In fact, I was told, Jesus deliberately waited until Lazarus had been dead long enough for decomposition to begin, so that the miracle would be all the more glorious. Lazarus’s resurrection also triggers the next phase of the gospel plot: it agitates the religious establishment, who worry that Jesus will accrue more and more followers, which could lead to violent suppression by the Roman authorities. Thus begins the conspiracy to kill him. Lazarus is a proof of divine identity, a link in the chain of events organized by God and carried out (unwittingly) by humans, and a dress rehearsal for the greater death and resurrection soon to come. What he isn’t, here, is a man. A man who dies twice. A man with two sisters.

“Sister of the dead man,” Martha is called. I, one of six sisters of the dead man, read and reread John 11 as if it were a novel redacted by a heavy-handed censor. I feel the desperation of the women who send that guilt trip of a phrase, “he whom you love,” not “he whom we love.” Had you been here, they repeat, he would not have died, an avowal of faith that I hear in a tone of fierce reproach. They believe so hard that the loss hurts worse. And the stench of the tomb? Martha is not protecting the others from a noxious odor; she is shielding herself and her sister from sensory confirmation of their brother’s death. This is all heretical. And, stupid as it may be, I have begun to cry as I write this.

As far as I know, Lazarus’s age at his first death is never revealed. My brother was 22, and he died not by illness but by another man’s hand. For practical reasons—autopsy, coroner’s report—seventeen days passed between the day he died and the day I saw his body. He had been embalmed, so he didn’t stink. Someone had shaved his face. I heard a guttural moan, and, to comfort my mother, I reached for her to find her reaching for me. It was my mouth making that sound, my body pitching forward to cover my brother’s, as if I would climb into the casket with him. I pressed my face against his smooth jaw. It’s both event and duration, dying—at least for the living—and the event repeats even as the duration holds. He is dead; no, he is not dead.

He is dead. Death, as many have noted, creates grammatical problems. What Roland Barthes names the “utterly unadjectival” state is pinned by an adjective. Lydia Davis puts the conundrums of tense typically succinctly: “When he is dead, everything to do with him will be in the past tense. Or rather, the sentence ‘He is dead’ will be in the present tense, and also questions such as ‘Where are they taking him?’ or ‘Where is he now?’” There is also the trouble of subject: to whom does “he” or “him” refer? The person it used to denote does not exist, or does not exist in the same form. But something stays—if not him, then what I called his body or, more reluctantly, his corpse. If such usage can be correct, Davis adds, then “for how long”? The body that comes forth from the tomb presents similar problems. If this, too, is his, is it the same?

Artists cannot resist the drama of the miraculous body. Giotto paints a white-faced figure swathed in white, a Lazarus bound so tightly that I imagine him hopping out like a child in a sack race. Sebastiano del Piombo renders a tumult of color in which a pink-clad Jesus lifts one hand toward heaven and extends the other toward a muscular Lazarus who strips a cloth from one arm while looking up at Jesus, the way you might undress before sex, urgently focused on another. I prefer Caravaggio’s. The likely apocryphal story is that Caravaggio modeled his Lazarus on the exhumed corpse of a recently deceased man. Lazarus, naked—convenient shadows and a man’s arm conceal his genitals—and sprawled diagonally across the painting’s center, does have that rigid languor peculiar to the dead. His eyes are closed. This resurrection, like Giotto’s, is not instantaneous. Most of the crowd stares at Jesus, who stands tall in the left foreground, pointing beyond Lazarus—to the empty grave? But Lazarus’s sisters, on the far right, bend over their brother. The nearer sister cradles his head. Her face is so close to his that she might be grazing his cheek with her own, it’s hard to tell. Their noses almost touch, like she’s trying to breathe his breath or smell his living scent. Here I find a shred of what I searched for in the biblical text: human love, powerless yet frantically active. One of this grief’s many paradoxes was that I felt as if I were capable of more than ever before in my life: nothing could frighten me except, as in D. W. Winnicott’s formulation, the catastrophe that has already happened. My love felt strong enough to produce anything, though it couldn’t. The force of my weakness surged through me.

I wasn’t alone in this. In the Iliad, Priam’s recovery of Hector’s body is a triumph of vulnerability over pride and power: “I have kissed the hand of the man who killed my son.” Gilgamesh violently laments over Enkidu’s corpse until maggots creep out of his nose, and then embarks on a futile quest for immortality. Many of Ovid’s metamorphoses occur in the extremity of grief as an excess of energy transforms the world, if not in the way the grieving wish: Phaethon’s sisters slowly harden and leaf into poplars at his grave; the stone Niobe weeps for her children; Hecuba, enraged about the murder of her son, morphs into a literal bitch, snapping and biting forever. Orpheus, pleading “for a loan,” makes “the bloodless shades weep.” Demeter lays waste to the earth. Something must change. In such moments, it is not hard to believe that you could resurrect one person, if you could find the right words or the right path to the underworld—and, crucially, out again. The problem seems one of method, not power. This essay is the fruit of a necromantic passion, and an emblem of failure. I remain sister to a dead man.

●

What counts as resurrection? A general rising of the dead, a return from the afterworld at the end of time in some physical embodiment, is specific to a small group of monotheistic religions: Zoroastrianism, Islam, Judaism, Christianity. Irksome sympathizers say that the dead person will “live” in memory. Reincarnation, especially prevalent in the belief systems collected under Hinduism, is an expansive view of resurrection. The “undead”—whether zombies or ghosts—cluster at the threshold of living again. Science fiction and the superrich try to upload the self to a mechanical container. Some physicists propose the eventuality of a quantum resurrection out there in this universe or another. The corpse fertilizes the cemetery grass. What I began seeking, though, was a straight-up rewinding, my own Lazarus, selfsame.

But even Lazarus’s resurrection, a case of supercharged healing, faces the problem of change. Although Lazarus aged like an ordinary man, he supposedly never smiled again. This might seem a surprising legend for Christianity, which made one particular resurrection the core of its salvific promise—but it is exactly the centripetal force exerted by resurrection that compels Christianity to struggle with the resurrected person, who must also have a resurrected body. (Christian personhood, attempting to overcome Hellenic body/soul dualism, embraced psychosomatic unity.) The conundrums that ensue are obvious even to children. When we were no more than five or six, after our mother turned off the lights, my sister and I used to discuss perplexities, including resurrection: Which of the bodies we have in life would rise again? What if we died before or after we had the ideal body, which would be, we agreed, old but not too old—say, sixteen? Would this body have all the same parts? Would it eat and excrete? Only many years later did I realize that some of the most famous Christian theologians have debated these exact questions.

The seed, the foundational Christian metaphor for the resurrected body, first appears in 1 Corinthians: “What you sow does not come to life unless it dies. And what you sow is not the body which is to be, but a bare kernel … So is it with the resurrection of the dead.” As with many biblical answers, even an ardent believer is likely left with more questions. Despite its Pauline source, the seed metaphor, which implies a transformation, did not go unchallenged as a paradigm. For hundreds of years, theologians advanced competing metaphors, from the body as river to resurrection as fish puking up drowned corpses. Would bodily resurrection entail some transformation, as in the seed or the river, or would it be a reassemblage of the material entirety, as in the vomiting fish or, less graphically, a statue melted down then reconstructed? The tension, at a deeper level, is a conflict between a body that continues to change, even after death, and a body fixed forever in stasis. This dilemma preoccupied Christians for many reasons, theological and not, but the tension also speaks to our refusal of the metamorphosis wrought by death and our simultaneous inability to push it aside.

“Pearl,” a Middle English poem attributed to the anonymous Gawain poet, portrays a vision in which a father encounters the daughter who died, his soul swept into some land adjacent to paradise. She died as a young child, but when he meets her again, her body is a grown woman’s. At first, he fails to recognize her, and the slow dawning is dramatized through a detailed description of her beautiful new form. They converse at cross-purposes, she having all the heartlessness of heaven and he, overcome with “love-longing,” filled with earthly misunderstanding, always looking back. He may even wish for the little girl he buried. Rereading “Pearl” recently, I wondered if the poet had had a daughter who died. It would surprise me, despite the intensely realistic portrait of a grieving father. Corpse poems—a lyric resurrection—ventriloquize the generic dead, the historic dead, the mythical dead, but only rarely the beloved dead. Despite my own love-longing, this makes sense: writing in my brother’s voice would violate the self he used to have and its very absence.

The same is true for imagining who he might be in a second life. Some attribute Lazarus’s dourness to having witnessed the underworld’s bleak state, but a more interesting explanation emerges in one of Robert Browning’s weirder persona poems, in which a skeptical physician examines a man who believes he has died and been brought back to life. The man—Lazarus, we quickly understand—is physically sound but utterly indifferent, even to the illness of his own child. For him, the “thread of life… / runs across some vast distracting orb / Of glory on either side that meagre thread, / Which, conscious of, he must not enter yet.” The knowledge gained by dying itself has de-formed Lazarus for living, left him stupefied and unsmiling.

●

The journey to and from the afterworld is invariably marked by difficulty—and, often, by some pivotal failure. It strikes me as a tragic fracture in the voluminous human imagination that even in myth and stories unpressured by fact, even in a faith rife with improbabilities, human resurrection can be a miracle, a perforation of the ordinary, but it can almost never be a fantasy fulfilled. Or perhaps it is less a fault than a choice: maybe we are choosing the pain of reality. Like waking from a pretty dream you know is a dream, like staring at your brother’s dead face. To be represented, the resurrection must be imperfect, a painting slashed by its painter right at the moment of completion.

After his wife died, Czesław Miłosz wrote a version of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth. His poem makes Orpheus’s failure an intrinsic consequence of his humanity, not an avoidable error. As he travels up, up, he hears—he thinks—the tap-tap of Eurydice’s feet behind. When he pauses, the footsteps halt; when he continues, they do too. Are these steps an echo or another person? “Under his faith a doubt sprang up,” a doubt whose only source is himself: he’s been given clear instructions, and he could just as easily interpret the footsteps as evidence of her perfect following, patiently pausing whenever he does. But, though he does keep walking without glancing back, he has already started to mourn the loss “of the human hope for the resurrection of the dead.” Both the hope and its failure to convince are human impulses, and even Orpheus could not sustain a belief in his own success. When he turns, everything is “as he expected … behind him on the path was no one.” None of Ovid’s outstretched arms and whirling winds. Eurydice’s long gone. Whether she was ever there at all is beside the point. Orpheus’s mind, not his movement, kept her dead.

If I, like Orpheus, had the method, would I, too, lack the power? I have to say yes, though I hate myself for it. The doubt springs up, about where they are and, worse, who they are, if they are. Likening Lazarus’s resurrection to a healing was a mistake: death isn’t the uttermost sickness—it is, in Barthes’ words, “the void of love’s relation.” This “void” is not just something going missing. When love’s everyday exchange becomes a one-way energy, all interplay breaks off. What remains is the Orphic journey, moving forward suspecting that any footsteps behind are merely echoes of your own. The drive to resurrect is born of love, but the resurrection itself cannot be born of love’s relation. Although Lazarus may have clumsily shuffled into the light on his own, first he had to be called. It is almost too painful to admit this, but that change we can neither abide nor ignore does force the question: Would he want to come back?

●

Recently, I dreamed that I was telling a story to my brother, who was three or four. We were sitting on the green-carpeted floor of a house that no longer exists. He wore red shorts, no shirt. His skin was deeply tanned, as always in summer. He kept glancing through the windows at the bright afternoon. I couldn’t hear my own voice; the story was silence to me. Then I realized I was dreaming, and that he was not present beyond the dream. I needed to hold him there. Despite his curiosity about outside’s pleasures, he would keep listening as long as I kept the tale going. So I talked and talked, still silent to myself. I felt fear—that I would run out of words—and a wonder that billowed like the gauzy curtains in the breeze. This is the best story I will ever tell, I thought, and I wished, even more upon waking, that I could hear this, my masterpiece.

That I kept talking seems an obvious sign of the overwhelming desire to communicate. That I could not hear my own voice suggests that, even asleep, my mind enforces the impossibility of communicating. What could I say, after all, that would reach him where he is now? Nonetheless, the dream dynamic remains the waking one. The Barbadian poet Kamau Brathwaite wrote a collection of poems addressed to the various dead entitled Elegguas, a play on “elegy” and Eleggua, the orisha of paths, thresholds and crossroads. In one poem, Brathwaite informs a beloved that others say she can’t come back: “as / if you cross some Great Divine Div- / ide or Water and you of all people / my love are now some Something / Dangerous & Other—some somethin / (g) Different & Alien & even Ugly. / Can you imagine how this make me feel?”

“As / if,” he says. The little phrase, broken by the line, captures all that disbelieving sorrow. “As if” is the beginning of the path to the dead. It is as if you are gone, so I will try to reach you, though you may be different, though you may not understand how living as if you are gone makes me feel. Goading myself through writing my brother’s eulogy, I felt as if I might die from the effort of expression, and yet people insisted that it was fortunate that I was a writer, not understanding that words could only truly be a consolation if they called him back.

At the climax of Abel Gance’s 1919 film J’accuse, the dead of World War I answer the call of a mysterious voice and rise from the battlefield, ungracefully, like sleepers with tingling limbs. “Diaphanous and fantastically heroic,” they stride away to determine if the living have made their sacrifice worthwhile. The dead soldiers are played by wounded veterans, including the writer Blaise Cendrars, a friend of Gance and Guillaume Apollinaire. Cendrars lost his right arm, first in the war and, he said, “a second time” in the film. Apollinaire, too, was wounded on the battlefield. Weakened by his injury, he died of the flu in 1918, two days before the war ended. Cendrars recounts how Apollinaire’s funeral procession, on its way from church to cemetery, “was besieged by a crowd of noisy celebrants of the Armistice, men and women with arms waving, singing, dancing, kissing, shouting deliriously the famous refrain of the end of the war: No, you don’t have to go, Guillaume / No you don’t have to go…” The eerie synchronicity of the popular song and the private wish reminds me that it is not hope that keeps us calling. Like Cendrars listening to the jubilant masses sing as if to his dead friend, there is nothing else for us to do, though the song will restore nothing, nor reach the ears of the dead man who passes through the chanting crowd. A failed spell, perhaps all speech ends up as direct address to the only one who can’t hear.

In their time, Gance and Cendrars were just two of a host of people talking to the dead—and, further, trying to call the dead back as visions or communicants. World War I was one of the mass-death events that make afterworlds a public preoccupation. Spontaneous psychic phenomena were common; a multitude of soldiers reported seeing their dead fellows on battlefields. Families pressured governments to identify and repatriate bodies buried in foreign land, and the black market in corpse recovery thrived, as frustrated relatives circumvented official channels. With or without a body to bury, many searched for something to fill the void of love’s relation. Spiritualism, both as an organization and a loose set of beliefs, surged during and after the war, as many, especially war victims, actively pursued messages from the dead, often through mediums. The war also led to a rise in unofficial or informal networks of support, material and not. In Paris, poor families living in a housing project, now called the “Cité du Souvenir,” each “adopted” a dead soldier, unrelated to them, and inscribed the names and dates of birth and death above their apartment doors. Such widespread loss from a single source created a different kind of love relation, a variety of social alliances formed by absence.

“Tombs die too,” Roland Barthes wrote in his linguistic monument to his mother, Mourning Diary, and the truth of those words is evident in the way we stroll past memorials to devastation that once vividly insisted on shoving the absence of the dead into the world of the living. In the Cité du Souvenir, where people presumably go about their daily business not thinking much about the adopted dead, a plaque at the entrance proclaims the intention “to honor the dead by an act of life,” and if honoring does happen, it may be in banal movements and an occasional flicker of awareness while hauling in groceries. Barthes believed that a monument must be something in flux: “an act, an action, an activity.” His theory of monuments reminds me of the Mapuche practice of amapüllün, in which the living retell the life stories of the dead at funerals, shaping a whole from the disparate events. The telling helps the dead person to move into the afterworld. The amapüllün seem to differ from Western eulogies because the act matters as much, if not more than, the content of the act. The making of the passage, not the passage made.

As difficult as it is, any communication to the dead must account or allow for some translation from this world to afterworld, in which a transformation of language or its necessity may also occur. An ethnography of Black women who “talk to the dead” in Lowcountry South Carolina shows how diverse “talking” can be: one woman speaks to her mother through songs, another to her sister in dreams, yet another communicates through the weaving of sweetgrass baskets. The dead do not always, or even mostly, reply in words. Maybe it doesn’t matter what story I summoned for my brother; maybe the dream’s true communication lay in his bright child face, suddenly still as he concentrated on what I was saying—or on something within himself that I could witness but not know. I did know that eventually he would leave me. Such exchange, everyday rather than extraordinary (unlike spirit possession), requires a willingness to be with those who are no longer here as they used to be—to, as I have struggled to do so far, release them from the form and voice they had before.

●

In January, my friend Carina and I stayed in a small town in northwest Puerto Rico while she finished her dissertation and I supposedly worked on my novel, but mostly researched resurrection. We both have familial ties to the island (her mother, my father), and we talked regularly about the feeling that arrived at times, strolling around the plaza for entertainment or stepping into the wild green of the mountains, as if we reprised the early lives of our grandmothers. Other times, eating breadfruit for breakfast or lying on a sunny rock by a river, we discussed the sense of embodying something much older, a pattern of life crafted by long-ago people, which it seemed hokey (at least to me) to name “ancestors”—though what else could you call them?

At night, on unsteady internet, I watched short segments of Let Each One Go Where He May, a film composed of thirteen extended tracking shots, in which two brothers follow the route upriver that their ancestors took when escaping from Dutch enslavement to the deep jungle of eastern Suriname. I watched it before sleeping because it was boring, its changes mostly subtle if noticeable at all: a shift in the canopy, different bends in the same wide river. Although the brothers’ boat had a motor, sometimes they rowed, and despite their modern clothes, in those moments I glimpsed the Saramakans three hundred years ago. A journey through space, it was also a journey through time.

The vision of my brother getting up out of his casket shatters again and again. In its place, I have turned to ritual acts, especially ones of embodiment, as the most attainable method of resurrecting him. And more than in the version of Christianity I grew up with, I find inspiration for these acts in the practices of African and indigenous religions, where rituals often entail improvising. A dance with specific steps, yet redefined by every dancer. There’s space for life to intrude, a particular life even—the one I am seeking.

In a beautiful essay on Garifuna rituals, Paul Christopher Johnson describes the dügü, a multiday ceremony in which the ancestral dead become present through their descendants “acting ancestrally, even becoming ancestral, in myriad routine, practical tasks”: they fish in the old way, in boats made the same way; they wear clothes dyed in achiote. Throughout the days of preparation, feasting, singing and dancing, the community acts as they once did. Spirit possession features in the dügü, but it is not the ultimate aim, nor the only mode of ancestral return. The embodiment surpasses mimesis; in the dügü’s space-time a resurrection occurs “through the dogged, selective performance of everyday labor … in the collective performance of this vivid tableau vivant, one with no spectators but the participants themselves.” As incarnations go, it is slow and sometimes tedious. Resurrection as ritual act surrenders the will to reverse time for residence in mythic no-time, and imagines the passageway as moving toward the dead with no intention of dragging them back or demanding they follow you.

For me, the first of these acts was accidental. The evening after my brother’s funeral, my family and a few friends gathered in the center of downtown Columbus, Ohio, at a hillside park on the banks of the Scioto River, to release paper lanterns. We had never done this before, and I can’t remember whose idea it was, or why we chose such a public location for an illegal activity. We wanted, I think, to see the lanterns glow on the surface of the dark river. From the start, everything went awry: the lanterns were hard to get going, and the wind was blowing the wrong direction, away from the river and toward downtown’s office buildings. One lantern, let fly too early, zipped toward a tree, with someone chasing madly after and leaping toward the branches just in time to keep the tree from becoming a torch. “That’s him,” one of my sisters said. And I knew what she meant.

I have been reluctant to name my brother here, afraid of reducing him to a character in my Orphic psychodrama. But it seems appropriate, now, to say that his name is Stephen, a sign that marks his many selves, including the final dazzling one, the potentiality of everything he could have been. He was an anarchic spirit, always mischievous, a troublemaker almost from the moment when he, a few days old, first strained to raise his head. As a baby, he only wanted to be held facing outward, toward the world, which quickly became a family symbol of his way of being. More than anyone I know, he noticed and delighted in the textures of existence. He would have laughed at our disaster of a memorial, and its disastrous execution seemed more fitting than the solemn beauty we’d intended. The last lantern whirled away above a skyscraper. Suddenly my mother said, “I’m going to roll down the hill,” and she did. We watched her come to a stop, laughing and apparently intact, at the bottom. The rest of us followed. Someone shouted: “Watch out for the stump!” Before I rolled down a second time, I paused to survey the hill for obstacles and, looking at these people I love—giddy, sprawled, bruised, flinging themselves into childish activity—I cried through a breathless laughter. These fugitive moments of intimacy with Stephen, as if he has once again approached too quietly for me to notice and surprised me by placing his big hand on my shoulder, feel like minor resurrections. They never stick; they never will.

The rituals accrue more deliberately too. In January, on my birthday, Carina and I drove an hour and a half to Cabo Rojo, an incomplete spiral of land in Puerto Rico’s southwest. I carried a small stone made from my brother’s ashes. I’d brought it from New York to leave somewhere on the island, I hadn’t yet decided where. Though I found myself vaguely ridiculous, I wanted part of him to stay where some of his ancestors were, in whatever form they now took. As we traced the edges of stunning cliffs I asked myself, Here? Here? On a narrow beach covered with stones of all colors, I looked out toward a natural bridge of stone that arches from the cliffside into the sea, and pictured it as a portal to an afterworld, having just seen a Haitian painting of the dead clustered on the other side of a body of water, glimpsed through a similar archway. Nearby, a young woman in a red bikini posed expertly for photos taken by her boyfriend. With her shifting smoothly from one sexy attitude to another, I felt too awkward to place the stone. The clash of my silent attempt at communion with the dead and the future Instagram carousel amused me, because it would have amused Stephen. Then, as if my amusement was his amusement, a different portal opened, keyhole-slim, through which he briefly slipped. In the clear waters of Bahía Sucia I did feel free to release the stone, knowing it would float away, then dissolve.

This summer, in Cyprus, where my brother never went, I repeated my invented ritual. The island’s easternmost point is the skinny Karpaz Peninsula, so remote and empty that you sense the sea on every side. At night, the dream of walking on water seduces. I’d brought another stone along because I wanted some part of him to have traveled with me. The sea is shallow for a long way out. I walked till I could no longer stand and then dove down, stone in my left hand. Before I could embed it in the sand, I lost my grip and though I looked, eyes burning from salt, it was gone.

Toward sunset I walked with a friend to the end of the beach, about half an hour, and then clambered up over rocks and dunes. The sea briefly disappeared from view; the landscape became an alien desert. The crest of the highest dune reveals below another sandy beach, longer and emptier and wilder than the one we left, walled by steep dunes and limestone cliffs so that it’s almost inaccessible except by sea. Stephen would have dared the climb down, heedless of the difficult trip back, and as my friend and I sat silently I believed for a second that I saw him coming toward us, far down the beach. Of course there was no one, and certainly not my brother. With one finger, I idly drew a thick spiral, in the style of Taíno petroglyphs I’d seen in Puerto Rico, in the sand. My friend noted that there was almost no wind, so the spiral might last till morning. We agreed to return and check. But we were tired when we woke, so we swam, and then it was time to leave. In my mind the spiral is there though it is not there.

Barthes again, like Brathwaite living “as if”: “Actually, as a matter of fact, always that: as if I were as one dead.” The most paradisiacal human trait is that we are inevitably surprised by death’s reality, despite its inevitability. The death of someone whom you love is a discovery of Death in the abstract as well as the particular: the appearance of disappearance, not only of the dead person, but of yourself. A quicksand pause: the absence of yourself from time. The sense of being ejected from time’s usual flow is common among the grieving, from my anecdotal polling. A writer who also lost a brother young, and violently, told me that at some point—he did not give a date or duration that must be exceeded—I would “rejoin time,” but, he added, if my experience turned out anything like his, some days, even decades later, would be “that first day after again.” Time, I suspect, will never move as it did before, even after I step back into it.

Being thrown out of time or immured in a fixed point within it is a way of dying with the one who has died, an unwilled and yet welcome journey that brings us nearer to being dead. My brother was shot in the chest three times, and every day I shape a gun out of my hand and press it three times to my chest. This ritual is a way of entering the event that I can never live, though I survive it: his dying, not mine. That I go on living while he does not still surprises me. Yet I now think the living hasn’t been continuous. If I have found any resurrection for sure, it’s mine, not my brother’s: as soon as I said, to another sister, “Stephen is dead,” it was as if I, like Barthes, were one dead—and then I came back to life, changed, like Lazarus always and probably until my final death glancing at that vast distracting orb beyond. This vision of the world coincides with the early Christian belief that they lived in a mythic age presently, an eschaton in which miracles indeed happen, like the raising of the dead. Time in the eschaton cannot be normal time; it stops, it loops, it mixes up states and tenses, it is adjacent to, but not within, eternity.

“Love is most nearly itself / when here and now cease to matter,” T. S. Eliot writes. For me, this is not a call to stasis, the statue rebuilt, but to envision love as perpetual motion, albeit not in one direction—abandoning, thus, the seed, and the river, unless it flows both ways. Maybe better to invoke the sea in which I cast my stones. Dante, famed voyager to afterworlds, fills the Paradiso with images of circular motion. And in the Commedia’s concluding lines, his last sight of heaven is an experience of merging with the cosmic revolutions: “But now my will and my desire, like wheels revolving / with an even motion, were turning with / the Love that moves the sun and all the other stars.” This is a beautiful truth that structures the universe, the culmination of the divine. But I believe this movement is human too, as human as those icky biological processes some early Christian theologians tried to erase: eating, digestion, excretion, the putrefaction of the corpse in the grave.

When Mary Magdalene meets the resurrected Jesus, she looks right at him, but does not recognize him, “supposing him to be a gardener.” Only when he addresses her does she realize who he is. She turns toward him. John does not describe the action, only the dialogue, so it is left to us to imagine what leads Jesus to say, in the Latin that has become metonym for the scene as a whole, Noli me tangere, usually translated as “do not touch me” or “do not hold me.” The noli me tangere encounter is another one artists cannot resist. There are myriad arrangements of Jesus and Mary Magdalene: his hand stretches out in refusal, she kneels, he bends, they both stand, they look at each other, one looks away. Almost always she reaches for him. Sometimes she makes contact. The multitude of portraits reflects the ambiguity of the simple phrase, which opens a range of possible relations. Perhaps he rejects her touch because he cannot bear the shock of intimacy, divided as they are by the fact of the resurrection. Perhaps, even as he speaks, he touches her, to hold her away from him. It’s possible, the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy argues, to translate the phrase as “do not wish to touch me.” If you do, then it becomes an exhortation to love the death too, because it is intrinsic to every life. Meanwhile, Mary’s hands hang in the air. Resurrection is Dante’s eternal rotation, “spurred on by flaming love”: it is the ongoing allegiance to keeping in sight the appearance of disappearance. It is living as if. It is a game of hands, an everlasting reaching after what escapes, what you love.

Art credits: Christine Elfman. Amaranth Extraction II (2016), silver gelatin print colored with amaranth dye; Fragment V (2019), cyanotype. All images courtesy of the artist.

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.