When they told us that we had no history, we told them that we had hawa. Like most children, who are born reporters, we were only repeating what grazed past our ears—that it was for the hawa, the air, that they, the people from the city, came to provincial towns like ours. Not to mock but to test their words, we sometimes tried to lick and suck the air like a popsicle. Nothing melted or burst inside our mouths even though we waited, at first with hope and then with hesitation. Later, when we learned that mosquitoes had become resistant to DDT because of continual exposure, we found an explanation: it was possible that we, too, had become resistant to the sweetness of the air in our provincial town, that its magic was available only to outsiders.

There were also days when this air didn’t seem enough. The three-limbed ceiling fans had tired of us; there were the power cuts, long, insistent, shameless, ruthlessly cursed by everyone. From our fathers and uncles we learnt to kick lampposts to bring electricity to our homes. Some electric current did occasionally leak into our houses—the fan moved like a saint before falling asleep. I remember my mother’s hand on summer afternoons, moving to the rhythm of our nostrils—this way and that, the palm-leaf hand fan gently distributing the air between my brother’s body and mine. Even when she dozed off, the hand continued to move over our thin bodies, sticky with sweat; by the time it reached her own face and body, there was hardly any air. This thing in her hand had once been a leaf—a palm leaf, its serrated edges chopped off, and its strong middle hardened by the sun. On Jamai Sasthi, after the folk rituals of worship on a hot day in May or June, drops of water would be sprinkled on the hand fan, which was then moved a few times above our heads—it was a prayer and blessing for the body to be cooled, for the air to be sweetened by water. This was our air conditioner.

We had never seen a real air conditioner. There were other such words that we knew only as abstractions, words used to write essays and pass examinations: development and global warming were two of them. Development, which many of us continue to mispronounce as “day-velopment,” seemed as far away as Jupiter, or our adulthood. Global warming, a subject that was just beginning to attain essay-subject status, was much lower down than afforestation and deforestation on the list of questions students wrote to pass examinations or get salaried government jobs. These words seemed as distant as the revenge of ghosts in the films that we watched. There was something else, a little more literal. The entry point to our town, right after crossing the river Mahananda, is called Air View More, named after the Air View Hotel that continues to stand there. From here the young Himalayas are visible—they look closer than they actually are, a new tin roof of a house shining like a gold tooth, the clouds always playful, light, off duty, sticky, the trees ancient guards that look like they would continue to stand watch over a city even after its last citizen has died. And yet, the oldest inhabitants of Siliguri, with their little farming of the English language, could only think of air when they stood here. “Air View.” How different the air must have seemed to them, how pigment-like and filled with promise and possibility. Now it’s the name of a bus and autorickshaw stop—ticket conductors shout “Air View Air View Air View” as diesel fumes enter us and tail pipes of vehicles spit dark clouds of smoke. The air has, like Milton’s darkness, become visible.

Today, if my nephew were to write an essay on globalization at school, he would likely repeat what his teachers have taught him, about how it erased differences among places, how everything was turned into a likeness of the other. What made the air in the provinces as unbreathable as the air in the city will need a book—that book, of the history of the changing quality of my country’s air, will be the real history of India in the 21st century.

●

Gaon ki hawa, sheher ki pani: the village air, the water of the city. It’s a Hindi idiom that holds within it what seems like an essentialist distinction between the village and the city, as well as the old association of “air” with the province, the small town and the village. It was to escape the city’s “abohawa,” or atmosphere, that one sought “hawa badal”—colloquially “a change of place,” but literally “a change of air.” It wasn’t just a tourist’s urge, it was also a doctor’s prescription. These places in the Indian provinces were first developed by the British in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as “sanatorium” towns for their heat-whacked population to recover and rest in convalescence—for India, tropical India, with its sun and mosquitoes, must have felt like a disease. They came to be seen as the equivalent of hospitals, particularly for those suffering from consumption and tuberculosis, and were of particular use “for the employees of the East India Company of the lower income groups,” writes Fred Pinn in his introduction to The Road of Destiny: Darjeeling Letters 1839.

Through these letters we discover how trees were felled and land “cleared” to make room for settlements. So Lt.-Col. Lloyd, the government agent in charge of establishing a sanatorium and constructing a road to Darjeeling, is advised by the Governor-General’s Council: “His Honour-in-Council will be glad to receive from you a report specifically on this point with a draft of the rules which you propose to establish for the different classes of native settlers including as well those who come to reside and open shops at Darjeeling as those who (are) desirous to clear and cultivate spots in the villages.” Newspapers based in Calcutta begin receiving letters to the editor, an indicator not just of the city’s growing interest in this new town that was being set up, but also, as Pinn emphasizes, to “encourage prospective entrepreneurs.” The basis of this entrepreneurship would be to sell the “opportunities here afforded to a patient of enjoying salutary air and exercise.”

From this assured—even if unverifiable—sense of the provincial town’s potential as a hospital would come letters and stories of hope and disappointment, depending on the health of the patients, but always—and inevitably—there would be an awareness and attention paid to the air, of it being almost of a different race from the air that had produced this illness. And not just by the British: twenty years later, Rabindranath Tagore took his daughter Renuka to another sanatorium town in the hope that this would help cure the thirteen-year-old’s tuberculosis, and there is a doctoral dissertation waiting to be written about Tagore’s recurring visits to the Indian provinces, through Mungpoo and Kurseong and Kalimpong, for the “change of air.” There were also other rewards. As one 1839 newspaper report in the Bengal Hurkaru shows: “Those who look to Darjeeling as the future Simla of the cocknies of Bengal will be glad to hear that the officers there are promised five hundred coolies from the Hazarebagh districts…”

At the same time, visitors to the area had their complaints about the provincial outposts—about rheumatism, for instance, and a lack of hygiene and comfort—which did not always live up to their marketing. A letter from “A LOVER OF TRUTH,” addressed to the editor of the Englishman, dated September 13, 1839, ends with reservation, bordering on anger: “As you have recommended persons to go up to Darjeeling during the Doorga Pooja holidays, I have thought it right to correct the most material of the errors which have appeared in your editorial article; for not only is the public misled as to the forwardness of the place, but much private inconvenience, or even worse than inconvenience, may be experienced.”

In the history of its beginning is a pattern that will harden into expectation and tradition, long after the British colonialists are replaced by Indian trading colonialists: the holiday taken to Darjeeling in autumn, for the Durga Puja, the quality of water in the town, even now an object of worry and concern among locals and tourists. It would come to destroy the region over the next 150 years: where once were trees now stand buildings, often illegally constructed and indifferent to the fragile ecosystem of the mountains. Run over by tourists through the year, except perhaps during the monsoons, when the landscape is regenerated even as parts of it give way to landslides, the region—and its air—now smells of diesel, kerosene and petrol, of automobiles that ferry tourists and take them on “seven-point” locations in the overcrowded town. In the letter that opens Chhinapatrabali, his travel memoir composed of letters to his niece, Tagore wrote about what the journey from this town to the hills was like in September 1887:

From Siliguri to Darjeeling, Sarala’s continuous wonderstruck exclamations: ‘O my, how wonderful’, ‘how amazing’, ‘how beautiful’—she kept nudging me and saying, ‘Rabi-mama, look, look!’ What to do, I must look at whatever she shows me—sometimes trees, sometimes clouds, sometimes an invincible blunt-nosed mountain girl, or sometimes so many things at the same time that the train leaves it all behind in an instant and Sarala is unhappy that Rabi-mama didn’t get to see it, although Rabi-mama is quite unrepentant. The train kept on going. Beli kept on sleeping. Forests, hilltops, mountains, streams, clouds and a vast number of flat noses and slant eyes began to be seen. Progressively it became wintry, and then there were clouds, and then Na-didi developed a cold, and then Bar-didi began to sneeze, and then shawls, blankets, quilts, thick socks, frozen feet, cold hands, blue faces, sore throats and, right after, Darjeeling.

(trans. Rosinka Chaudhuri)

Some of this geography persists, as do the props that such a life necessitates. But not the air, whose smell and life now has to be imagined.

●

The childlike thrill of going to the mountains remains. We don’t say the word but we grow restless to roll down the car windows as soon as we are close to Sukna—we want the air on our face, as if it were a mist spray. But it is no longer the air that I, at fourteen, once wrote to the poet Jayanta Mahapatra about, telling him that to live here is to smell of this rainy air. Instead, fumes from road-building material, tar burning inexhaustibly, as if that was its blood, fill the air; there’s also the fine dust of cement—always, always, a building is coming up somewhere. Ubiquitous now, as if it were the sound of the natural world, is the metallic teeth-grinding sound of tiles being cut, for, in this new India, tiles are slapped on to all kinds of available surface, houses, toilets, temples. The slim railway tracks of what is called the “toy train,” for its size as much as its doll-like demeanor, lie on one side of this road that started its life in 1839. Quite often, I see white tourists in these small coaches—they wave back when my little niece waves at them.

For nearly the entirety of the first decade of my life, my friends and I referred to all white people as “Ingrej,” Englishmen. I say all, though the sample size would not be more than ten, or perhaps even five—we knew them from books, and the five or ten we saw with awe and curiosity when they visited a Christian Nepali neighbor’s house we treated as if they had come out of those books and would have to return to them soon. Maybe they too had come for the air? We discussed, with scientific seriousness, whether characters in storybooks felt asphyxiated and needed oxygen as much as we did. It is only now that I realize that we never used the word oxygen—it was always hawa, air. The Sanskrit word for the living is those who have pran—it also means those who breathe.

“It was in the air…” is a sophisticated expression that we took for granted, and treated almost literally. We became aware of the existence of Baikunthapur forest, then on the fringe of our town, in spring, as spores and pollen burst into the air and we began to sneeze. When the late afternoon air suddenly turned cool, as if it had passed through a freezer, the neighborhood women read it like news: it’s raining in the hills, they announced. The many Bengali songs about air—“khola hawa,” fresh air; “pagla hawa,” crazy wind—erupted from the lips of visitors. They were not specific to our region but their invocation at timely moments emphasized their pertinence. It really must have been something about the air in the provinces that changed city dwellers. When they visited us, usually on their way to Darjeeling or Sikkim, they said they felt freer, as if something inside them had been allowed to uncoil. Perhaps this is where it comes from, my understanding of freedom as the volume of air that can be held by our hair.

But the Indian provinces, once associated with the pastoral, with hawa badal, are now its most polluted regions. Those British-built sanatorium towns have been pumped with the steroids of “development”—there is a war on trees, and large populations of plant life, aged and young, are being cleared overnight to build “roads,” a metonymy for a robust common good. In the eastern and western Himalayas, in Goa, in Kodaikanal, in Dehradun and Darjeeling, Uttarakhand and Sikkim, once places of meditation and repose, rest and calm, of a natural world of plants and animals that made them arcadian “holiday homes,” first of the British and later of middle-class Indians, an extremist attack has been unfolding for nearly three decades, simultaneous with the opening up of the Indian economy. Roads and railway tracks, markers of progress used to convince a local population by the European colonizer before Indian independence, are now shiny badges of development in these towns that no longer want to remain “small.” In India’s northeast, dams—which were part of the first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s project of urgent nation building, and which continue to find support, irrespective of the changes in political dispensation—have been helping cause floods and landslides that wipe away human and plant settlements.

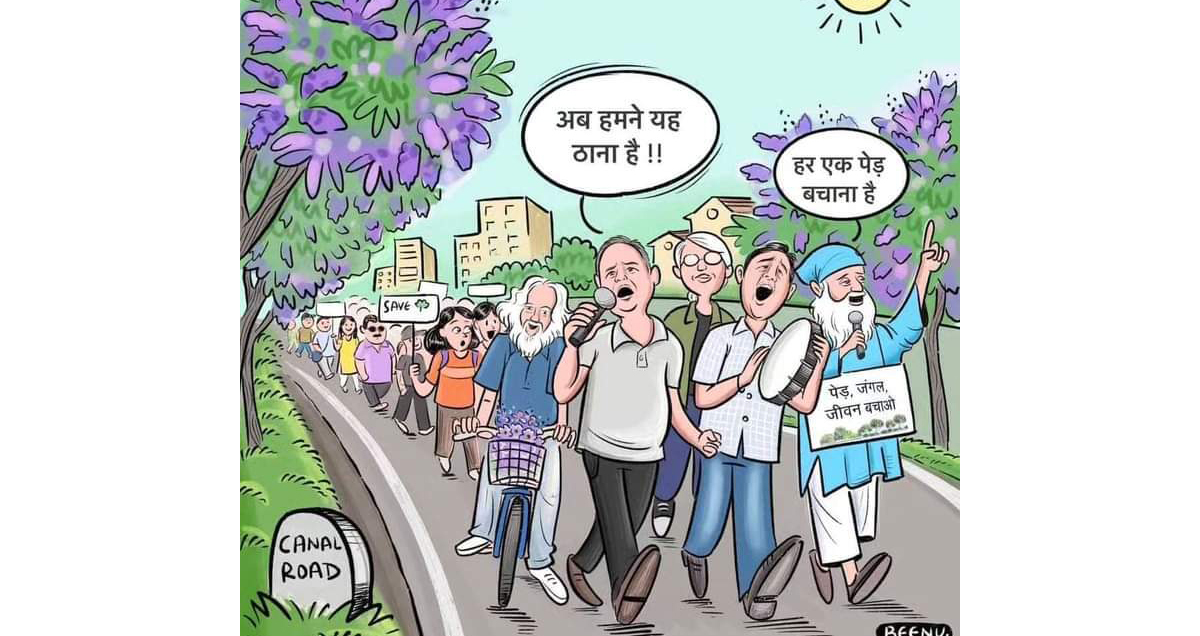

Over the last year, I have seen Siliguri, my hometown in sub-Himalayan Bengal, lose almost its entire public tree cover. The air is unbreathable, with the AQI often above 250 during the winter. These regions, once beneficiaries of an odd mix of benign neglect and affection, now touched by the demand for equitable attention and distribution of national resources, are losing their genetic character. As central and state governments have abetted their destruction in their zealous collaboration with the agents of development, real estate corporations, dam and hydroelectric projects, roads and railways and, of course, the tourism industry, whose razzmatazz has drugged a neglected people, the only protests have come from environmentalists and artists. The writer and artist Amruta Patil has urged visitors to Goa—or any rural region—to bring nothing but their humility, or else stay away, for that seems to be the only way to save it; the writer Krishna Shastri Devulapalli and journalist Smriti Lamech have made similar pleas about protecting their Kodaikanal (here’s Devulapalli: “Kodaikanal, the hapless, once idyllic, hill town in the Western Ghats has, of late, been abused so brutally by tourism that its unique, priceless flora and fauna is in grave danger”); the historian Mou Banerjee has raised awareness about the Ayodhya forest burning—or being burned down, who can say—near her hometown in Bengal’s Purulia; the poet and teacher Sebanti Ghosh has been writing about how the construction of the SAARC highway has killed thousands of trees in Siliguri. The poet and translator Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, who is almost as old as the Indian nation, recently participated in a citizens’ march to “protect the environment.” Here he is, on his bicycle, in the poster, surrounded by speech bubbles that vow to “save every tree” in Uttarakhand’s Dehradun, a state where towns and villages are sinking and landslides have wiped away crowded human settlements:

●

In Raja Rammohunpur, it sometimes seemed that we went to the University of North Bengal not so much for the classes as for the campus: Dryden and Webster and Blake would be discussed in many other classrooms in India, but how could one not walk through Salbon, the gentle forest of sal trees where the annual convocation was held, with a melancholic brook running by, its shape and girth dependent on the monsoon, and not experience something akin to what Wordsworth had in Tintern Abbey?

—And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.

“The living air.” A few days ago, I went to the university campus after many years, to drop my husband off at his workplace, though my secret intention was to see the multitudes of jarul trees in bloom near the cricket field where we once cheered the boys in our class as the English department beat the commerce department, a victory that had metaphorical appeal for our unemployed lives at that time. The trees did not disappoint—their purple heads, robust, almost with the confidence of those that know that they are somehow immortal, looked slightly magical-realist. By this I perhaps mean that it seemed something had displaced them from a dreamier world into this one, as if the scene belonged more to art, to something that had been produced by a human mind, than to the simplicity or the connivance of the earth. Unlike the many trees in the Salbon or the Padmaja Park on campus that had grown on their own, brought there by bird or bee or a seed sticking to the underside of human slippers, these were the result of an afforestation drive by—I presume—the Forest Department. Afforestation, the subject of the essays we had to learn to write in school, imagining a world where trees were being killed every moment, everywhere, for which we needed to plant twice as many, so that it seemed like something that could only be fiction, had moved from the examination-question paper to real life. That was evident from the monoculture—the same species of trees planted in a neighborhood as if it were a lab or pills inside a box.

Not far from the purple crown of jarul flowers—whose English name is the “Pride of India”!—that seemed to be biting into the sky was an electronic board that hadn’t existed when I was a student a little more than two decades ago. It gave the current temperature and AQI, the Air Quality Index. I think my nephew and niece will now learn how to write essays on Air Quality Index like I once had to about deforestation and global warming. They might get better grades than I did —they won’t have to imagine an AQI of 250 or 300 in the way I had to imagine the world overheating. Even air has become an acronym: AIR is All India Rank, an assessment system used for the competitive exams that allow entry into educational institutions and guarantee jobs. Though it might seem from such a deliberate expansion of the letters in the word that air has grown since my childhood, the opposite has happened—the volume of air on earth has, of course, remained unchanged, but no one uses the phrase hawa badal anymore.

When they told us that we had no history, we told them that we had hawa. Like most children, who are born reporters, we were only repeating what grazed past our ears—that it was for the hawa, the air, that they, the people from the city, came to provincial towns like ours. Not to mock but to test their words, we sometimes tried to lick and suck the air like a popsicle. Nothing melted or burst inside our mouths even though we waited, at first with hope and then with hesitation. Later, when we learned that mosquitoes had become resistant to DDT because of continual exposure, we found an explanation: it was possible that we, too, had become resistant to the sweetness of the air in our provincial town, that its magic was available only to outsiders.

There were also days when this air didn’t seem enough. The three-limbed ceiling fans had tired of us; there were the power cuts, long, insistent, shameless, ruthlessly cursed by everyone. From our fathers and uncles we learnt to kick lampposts to bring electricity to our homes. Some electric current did occasionally leak into our houses—the fan moved like a saint before falling asleep. I remember my mother’s hand on summer afternoons, moving to the rhythm of our nostrils—this way and that, the palm-leaf hand fan gently distributing the air between my brother’s body and mine. Even when she dozed off, the hand continued to move over our thin bodies, sticky with sweat; by the time it reached her own face and body, there was hardly any air. This thing in her hand had once been a leaf—a palm leaf, its serrated edges chopped off, and its strong middle hardened by the sun. On Jamai Sasthi, after the folk rituals of worship on a hot day in May or June, drops of water would be sprinkled on the hand fan, which was then moved a few times above our heads—it was a prayer and blessing for the body to be cooled, for the air to be sweetened by water. This was our air conditioner.

We had never seen a real air conditioner. There were other such words that we knew only as abstractions, words used to write essays and pass examinations: development and global warming were two of them. Development, which many of us continue to mispronounce as “day-velopment,” seemed as far away as Jupiter, or our adulthood. Global warming, a subject that was just beginning to attain essay-subject status, was much lower down than afforestation and deforestation on the list of questions students wrote to pass examinations or get salaried government jobs. These words seemed as distant as the revenge of ghosts in the films that we watched. There was something else, a little more literal. The entry point to our town, right after crossing the river Mahananda, is called Air View More, named after the Air View Hotel that continues to stand there. From here the young Himalayas are visible—they look closer than they actually are, a new tin roof of a house shining like a gold tooth, the clouds always playful, light, off duty, sticky, the trees ancient guards that look like they would continue to stand watch over a city even after its last citizen has died. And yet, the oldest inhabitants of Siliguri, with their little farming of the English language, could only think of air when they stood here. “Air View.” How different the air must have seemed to them, how pigment-like and filled with promise and possibility. Now it’s the name of a bus and autorickshaw stop—ticket conductors shout “Air View Air View Air View” as diesel fumes enter us and tail pipes of vehicles spit dark clouds of smoke. The air has, like Milton’s darkness, become visible.

Today, if my nephew were to write an essay on globalization at school, he would likely repeat what his teachers have taught him, about how it erased differences among places, how everything was turned into a likeness of the other. What made the air in the provinces as unbreathable as the air in the city will need a book—that book, of the history of the changing quality of my country’s air, will be the real history of India in the 21st century.

●

Gaon ki hawa, sheher ki pani: the village air, the water of the city. It’s a Hindi idiom that holds within it what seems like an essentialist distinction between the village and the city, as well as the old association of “air” with the province, the small town and the village. It was to escape the city’s “abohawa,” or atmosphere, that one sought “hawa badal”—colloquially “a change of place,” but literally “a change of air.” It wasn’t just a tourist’s urge, it was also a doctor’s prescription. These places in the Indian provinces were first developed by the British in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as “sanatorium” towns for their heat-whacked population to recover and rest in convalescence—for India, tropical India, with its sun and mosquitoes, must have felt like a disease. They came to be seen as the equivalent of hospitals, particularly for those suffering from consumption and tuberculosis, and were of particular use “for the employees of the East India Company of the lower income groups,” writes Fred Pinn in his introduction to The Road of Destiny: Darjeeling Letters 1839.

Through these letters we discover how trees were felled and land “cleared” to make room for settlements. So Lt.-Col. Lloyd, the government agent in charge of establishing a sanatorium and constructing a road to Darjeeling, is advised by the Governor-General’s Council: “His Honour-in-Council will be glad to receive from you a report specifically on this point with a draft of the rules which you propose to establish for the different classes of native settlers including as well those who come to reside and open shops at Darjeeling as those who (are) desirous to clear and cultivate spots in the villages.” Newspapers based in Calcutta begin receiving letters to the editor, an indicator not just of the city’s growing interest in this new town that was being set up, but also, as Pinn emphasizes, to “encourage prospective entrepreneurs.” The basis of this entrepreneurship would be to sell the “opportunities here afforded to a patient of enjoying salutary air and exercise.”

From this assured—even if unverifiable—sense of the provincial town’s potential as a hospital would come letters and stories of hope and disappointment, depending on the health of the patients, but always—and inevitably—there would be an awareness and attention paid to the air, of it being almost of a different race from the air that had produced this illness. And not just by the British: twenty years later, Rabindranath Tagore took his daughter Renuka to another sanatorium town in the hope that this would help cure the thirteen-year-old’s tuberculosis, and there is a doctoral dissertation waiting to be written about Tagore’s recurring visits to the Indian provinces, through Mungpoo and Kurseong and Kalimpong, for the “change of air.” There were also other rewards. As one 1839 newspaper report in the Bengal Hurkaru shows: “Those who look to Darjeeling as the future Simla of the cocknies of Bengal will be glad to hear that the officers there are promised five hundred coolies from the Hazarebagh districts…”

At the same time, visitors to the area had their complaints about the provincial outposts—about rheumatism, for instance, and a lack of hygiene and comfort—which did not always live up to their marketing. A letter from “A LOVER OF TRUTH,” addressed to the editor of the Englishman, dated September 13, 1839, ends with reservation, bordering on anger: “As you have recommended persons to go up to Darjeeling during the Doorga Pooja holidays, I have thought it right to correct the most material of the errors which have appeared in your editorial article; for not only is the public misled as to the forwardness of the place, but much private inconvenience, or even worse than inconvenience, may be experienced.”

In the history of its beginning is a pattern that will harden into expectation and tradition, long after the British colonialists are replaced by Indian trading colonialists: the holiday taken to Darjeeling in autumn, for the Durga Puja, the quality of water in the town, even now an object of worry and concern among locals and tourists. It would come to destroy the region over the next 150 years: where once were trees now stand buildings, often illegally constructed and indifferent to the fragile ecosystem of the mountains. Run over by tourists through the year, except perhaps during the monsoons, when the landscape is regenerated even as parts of it give way to landslides, the region—and its air—now smells of diesel, kerosene and petrol, of automobiles that ferry tourists and take them on “seven-point” locations in the overcrowded town. In the letter that opens Chhinapatrabali, his travel memoir composed of letters to his niece, Tagore wrote about what the journey from this town to the hills was like in September 1887:

Some of this geography persists, as do the props that such a life necessitates. But not the air, whose smell and life now has to be imagined.

●

The childlike thrill of going to the mountains remains. We don’t say the word but we grow restless to roll down the car windows as soon as we are close to Sukna—we want the air on our face, as if it were a mist spray. But it is no longer the air that I, at fourteen, once wrote to the poet Jayanta Mahapatra about, telling him that to live here is to smell of this rainy air. Instead, fumes from road-building material, tar burning inexhaustibly, as if that was its blood, fill the air; there’s also the fine dust of cement—always, always, a building is coming up somewhere. Ubiquitous now, as if it were the sound of the natural world, is the metallic teeth-grinding sound of tiles being cut, for, in this new India, tiles are slapped on to all kinds of available surface, houses, toilets, temples. The slim railway tracks of what is called the “toy train,” for its size as much as its doll-like demeanor, lie on one side of this road that started its life in 1839. Quite often, I see white tourists in these small coaches—they wave back when my little niece waves at them.

For nearly the entirety of the first decade of my life, my friends and I referred to all white people as “Ingrej,” Englishmen. I say all, though the sample size would not be more than ten, or perhaps even five—we knew them from books, and the five or ten we saw with awe and curiosity when they visited a Christian Nepali neighbor’s house we treated as if they had come out of those books and would have to return to them soon. Maybe they too had come for the air? We discussed, with scientific seriousness, whether characters in storybooks felt asphyxiated and needed oxygen as much as we did. It is only now that I realize that we never used the word oxygen—it was always hawa, air. The Sanskrit word for the living is those who have pran—it also means those who breathe.

“It was in the air…” is a sophisticated expression that we took for granted, and treated almost literally. We became aware of the existence of Baikunthapur forest, then on the fringe of our town, in spring, as spores and pollen burst into the air and we began to sneeze. When the late afternoon air suddenly turned cool, as if it had passed through a freezer, the neighborhood women read it like news: it’s raining in the hills, they announced. The many Bengali songs about air—“khola hawa,” fresh air; “pagla hawa,” crazy wind—erupted from the lips of visitors. They were not specific to our region but their invocation at timely moments emphasized their pertinence. It really must have been something about the air in the provinces that changed city dwellers. When they visited us, usually on their way to Darjeeling or Sikkim, they said they felt freer, as if something inside them had been allowed to uncoil. Perhaps this is where it comes from, my understanding of freedom as the volume of air that can be held by our hair.

But the Indian provinces, once associated with the pastoral, with hawa badal, are now its most polluted regions. Those British-built sanatorium towns have been pumped with the steroids of “development”—there is a war on trees, and large populations of plant life, aged and young, are being cleared overnight to build “roads,” a metonymy for a robust common good. In the eastern and western Himalayas, in Goa, in Kodaikanal, in Dehradun and Darjeeling, Uttarakhand and Sikkim, once places of meditation and repose, rest and calm, of a natural world of plants and animals that made them arcadian “holiday homes,” first of the British and later of middle-class Indians, an extremist attack has been unfolding for nearly three decades, simultaneous with the opening up of the Indian economy. Roads and railway tracks, markers of progress used to convince a local population by the European colonizer before Indian independence, are now shiny badges of development in these towns that no longer want to remain “small.” In India’s northeast, dams—which were part of the first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s project of urgent nation building, and which continue to find support, irrespective of the changes in political dispensation—have been helping cause floods and landslides that wipe away human and plant settlements.

Over the last year, I have seen Siliguri, my hometown in sub-Himalayan Bengal, lose almost its entire public tree cover. The air is unbreathable, with the AQI often above 250 during the winter. These regions, once beneficiaries of an odd mix of benign neglect and affection, now touched by the demand for equitable attention and distribution of national resources, are losing their genetic character. As central and state governments have abetted their destruction in their zealous collaboration with the agents of development, real estate corporations, dam and hydroelectric projects, roads and railways and, of course, the tourism industry, whose razzmatazz has drugged a neglected people, the only protests have come from environmentalists and artists. The writer and artist Amruta Patil has urged visitors to Goa—or any rural region—to bring nothing but their humility, or else stay away, for that seems to be the only way to save it; the writer Krishna Shastri Devulapalli and journalist Smriti Lamech have made similar pleas about protecting their Kodaikanal (here’s Devulapalli: “Kodaikanal, the hapless, once idyllic, hill town in the Western Ghats has, of late, been abused so brutally by tourism that its unique, priceless flora and fauna is in grave danger”); the historian Mou Banerjee has raised awareness about the Ayodhya forest burning—or being burned down, who can say—near her hometown in Bengal’s Purulia; the poet and teacher Sebanti Ghosh has been writing about how the construction of the SAARC highway has killed thousands of trees in Siliguri. The poet and translator Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, who is almost as old as the Indian nation, recently participated in a citizens’ march to “protect the environment.” Here he is, on his bicycle, in the poster, surrounded by speech bubbles that vow to “save every tree” in Uttarakhand’s Dehradun, a state where towns and villages are sinking and landslides have wiped away crowded human settlements:

●

In Raja Rammohunpur, it sometimes seemed that we went to the University of North Bengal not so much for the classes as for the campus: Dryden and Webster and Blake would be discussed in many other classrooms in India, but how could one not walk through Salbon, the gentle forest of sal trees where the annual convocation was held, with a melancholic brook running by, its shape and girth dependent on the monsoon, and not experience something akin to what Wordsworth had in Tintern Abbey?

“The living air.” A few days ago, I went to the university campus after many years, to drop my husband off at his workplace, though my secret intention was to see the multitudes of jarul trees in bloom near the cricket field where we once cheered the boys in our class as the English department beat the commerce department, a victory that had metaphorical appeal for our unemployed lives at that time. The trees did not disappoint—their purple heads, robust, almost with the confidence of those that know that they are somehow immortal, looked slightly magical-realist. By this I perhaps mean that it seemed something had displaced them from a dreamier world into this one, as if the scene belonged more to art, to something that had been produced by a human mind, than to the simplicity or the connivance of the earth. Unlike the many trees in the Salbon or the Padmaja Park on campus that had grown on their own, brought there by bird or bee or a seed sticking to the underside of human slippers, these were the result of an afforestation drive by—I presume—the Forest Department. Afforestation, the subject of the essays we had to learn to write in school, imagining a world where trees were being killed every moment, everywhere, for which we needed to plant twice as many, so that it seemed like something that could only be fiction, had moved from the examination-question paper to real life. That was evident from the monoculture—the same species of trees planted in a neighborhood as if it were a lab or pills inside a box.

Not far from the purple crown of jarul flowers—whose English name is the “Pride of India”!—that seemed to be biting into the sky was an electronic board that hadn’t existed when I was a student a little more than two decades ago. It gave the current temperature and AQI, the Air Quality Index. I think my nephew and niece will now learn how to write essays on Air Quality Index like I once had to about deforestation and global warming. They might get better grades than I did —they won’t have to imagine an AQI of 250 or 300 in the way I had to imagine the world overheating. Even air has become an acronym: AIR is All India Rank, an assessment system used for the competitive exams that allow entry into educational institutions and guarantee jobs. Though it might seem from such a deliberate expansion of the letters in the word that air has grown since my childhood, the opposite has happened—the volume of air on earth has, of course, remained unchanged, but no one uses the phrase hawa badal anymore.

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.