There is a recent movie called Annihilation, where a group of women scientists are sent by the American government to travel inside of a mysterious and ominously expanding territory, enveloped by an iridescent cloud, that is referred to as “the Shimmer.” Prior to the expedition, this shimmering territory is viewed from a nearby military station post, where, despite all technological advancement, scientific knowledge is deemed insufficient to stop its spread. When the women scientists find themselves inside of this Shimmer, the conventional sense of time disappears and they are beguiled by a beautiful, wild nature—a nature that seems to penetrate their bodies. One of the women is eaten by a monstrous, mutant bear; another woman is mauled by a gargantuan alligator and later turns into a flowering tree. The boundaries between entities collapse: past and present, outside and inside, animal, plant and human. It is a grotesque jouissance, an orgasm of nature that exists inside the Shimmer. Traveling closer to the source of the mesmerizing glow, the protagonist, Lena, played by Natalie Portman, discovers herself in a sort of cave where she is penetrated by light that creates her double, leaving her as if burning into ash inside of this uterine space.

A general consensus exists among my mommy friends that this film is about the postpartum experience—which is not just an experience, but an introduction to a liminal form of life. In the early days of my transition to motherhood, I discovered my new species congregating by the community fountain in the center of my apartment compound in Manhattan’s East Village: blank-eyed and diaper-bagged bodies that had fulfilled their biological mission, they could be spotted eating bits of food found sticking to their eternal yoga pants, rocking a stroller with a robotic foot. The fountain’s water was always lit up with neon-purple lights, and there was always a flock of new moms with strollers walking for hours around its circumference, as if in a trance, while elderly people with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers sat on the surrounding benches, eating snacks. Fountain of oblivion, we called it. The sound of gushing water helped our babies fall asleep, while the moms were all collectively daydreaming of the next cup of coffee. When addressing each other, we were identified by our children’s ages, which were counted in days or weeks; meanwhile, people who previously called me by name, such as the hospital doctor, now suddenly referred to me as “mom.” I particularly connected with one mom, let’s call her A9, a former theology student, over our shared cracked-nipple woes. Once the fountain of oblivion did its magic, we would signal to each other by lifting one hand to the mouth, meaning that it was time for coffee. At the nearby coffee shop, we would take turns watching each other’s babies while we went to the bathroom. Gifting each other the opportunity to shit in solitude cemented our bond.

Does Annihilation’s Lena—doubled, her old self destroyed, a new one forged in the Shimmer’s core—make it out? This question was existential to A9 and me then. It had to do with the survival of our species.

My transition to motherhood had been accompanied by physical changes that made me identify with almost anything in the genre of sci-fi horror. Not only was my postpartum hair loss weaving a red carpet on the ground, but my skin became brown and ashen, peeling off my body as if I were an onion. After giving birth, time for me seemed to have warped through the prism of sleep deprivation and I often felt that I’d been abducted by aliens, then returned to earth—seemingly the same, but qualitatively a different person. When I was not peeling off of myself, I was leaking out of myself. There were the constant streams of milk; retaining urine, blood and other such things became such a challenge that I continued to wear an adult diaper for months after giving birth. I developed a spinal-fluid drip, which means that the fluid protecting my brain from bumping into the skull was draining down my spine, a condition that exacerbated the sensation of losing my mind. At some point in this journey, I encountered obstacles that required that I—or at least whatever remained of me—self-cannibalize, and so I consumed my own placenta after shredding it in a mixer with some strawberries. But simultaneously with all this scary body shit, there was a strange feeling of the numinous—a communion with the sacred. The boundary between my skin and the world was evaporating before my eyes. This feeling was dangerous and weirdly erotic—my body expanding and the world penetrating me as my sense of self was being annihilated by the merger.

●

Res extensa—the extension of matter into space. Writing on the cusp of the European Enlightenment, the French philosopher and scientist René Descartes separated the res extensa—which he used interchangeably with res corporea, the extension of the body—from the res cogitans, the mind. This was the basis of what is known in philosophy as dualism—the division between the mind and the body as separate entities. But Descartes did not view them as equals. While we have direct access to the contents of our minds, he argued, our bodies are compromised by their intimate implication in the realm of appearance and sensation. In fact, from this perspective, the body was not only separate from the mind but entirely unnecessary. For the existence of his mind, Descartes concluded, “There is no need of any place, nor does it depend on any material thing; so that this ‘me,’ that is to say the soul by which I am what I am, is entirely distinct from body.” Thus were planted the seeds of an idea that has remained ingrained in Western thinking today, despite all those hours of yoga: that the body cannot be truly known and ought not, therefore, to be fully trusted.

The position of the res cogitans is largely unattainable for women, at least when viewed from the perspective of subject formation in Western metaphysics. In the Western philosophical tradition, women have long been conflated with matter and space. For better or worse: matter (and materiality by extension) comes from the Latin mater, or mother. Aristotle, in The Generation of Animals, while discussing sexual difference and the generation of offspring, famously writes that “the male provides the form and the principle of movement. The female provides the body, in other words, the material.” Until the seventeenth century or so, it was widely accepted that the fetus was formed out of menstrual blood (as opposed to the egg), which Aristotle referred to as the “prime matter”—proto hyle. On this theory, without the “male” activating cause, i.e. the sperm, matter lacked the ability to “concoct” itself, and so would decay and leak out of the uterine receptacle. This inability to “concoct”—and the Chernobylesque horror of an infinitely expanding materiality—makes me think that contemporary postpartum experience continues to be within the bounds of the Aristotelian paradigm. Pregnancy is beautiful and all, but in the end, you are supposed to keep it together—to concoct.

According to the gynecologist, one should abstain from sex for two months after giving birth. Everything is very sensitive down there—and then there is always that chance that the wall between your asshole and your vagina will have collapsed, a condition called “pelvic organ prolapse.” Nonetheless, one is encouraged to be a good sport: things will get back to normal. All the new mommy forums and the “your day with a newborn” YouTube channels proclaim the mantra: two months no sex, six months for the abdominal muscles to heal, and then you are “back to normal.” But, after my firsthand experience, I am not so sure that women actually make it out of the shimmering space of the postpartum experience. More likely, they combust and prolapse in it, and it is not them but their doubles who emerge out of its haze. It is their doubles who greet you with “It’s going great!” when you eventually do meet for fucking brunch.

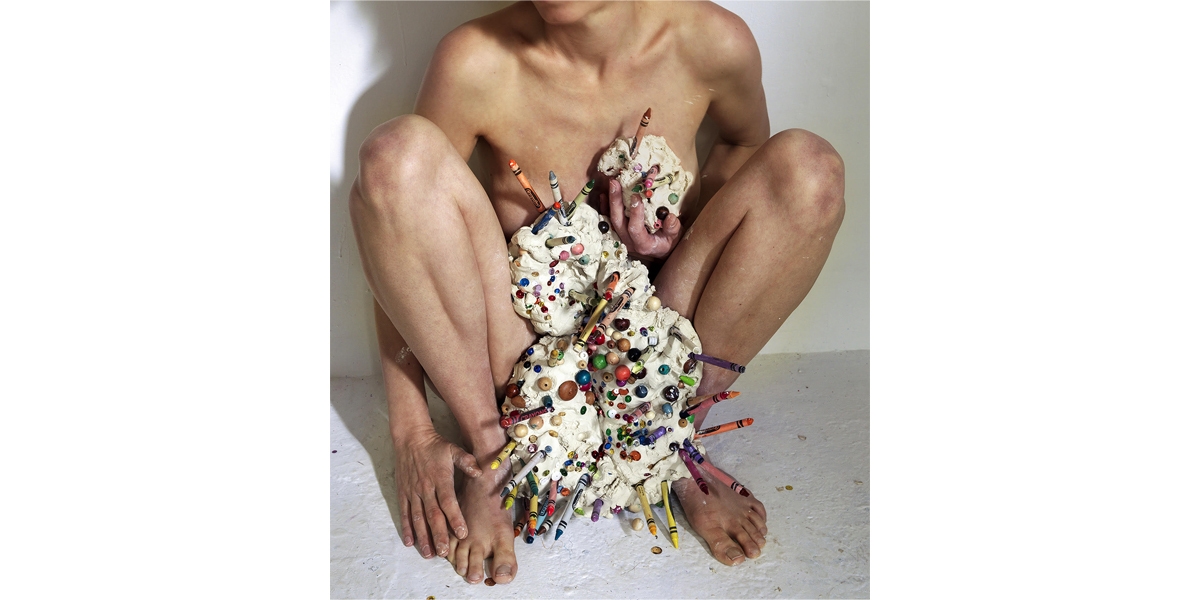

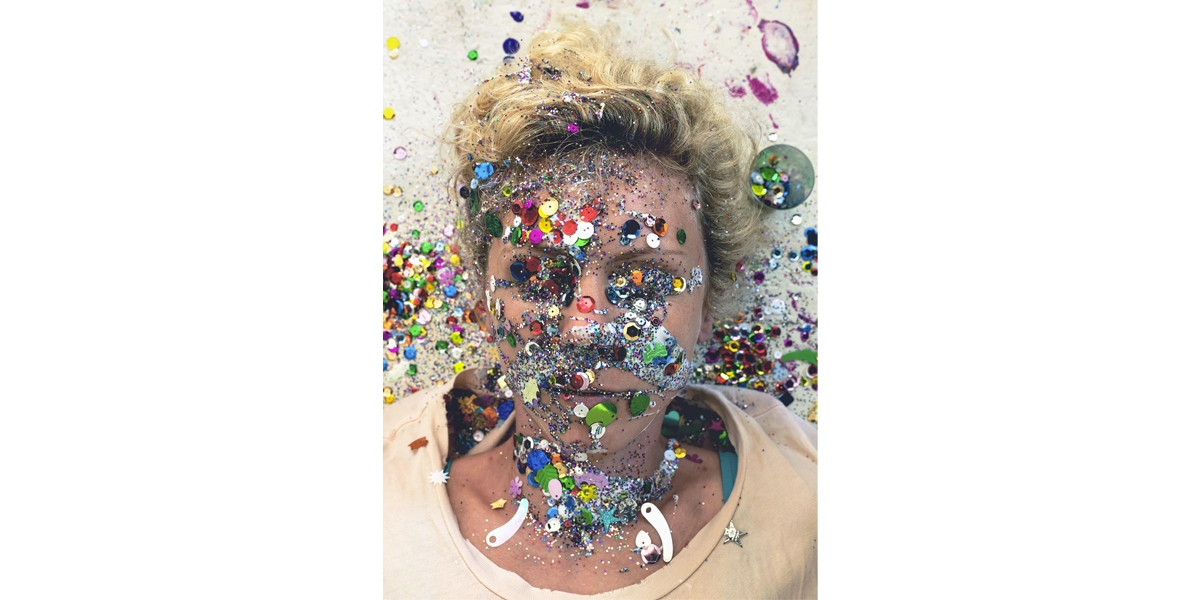

You can often recognize these doubles by their peculiar preference for all things glitter: glitter bags, glitter pens, glitter cell-phone covers. In some cases, such as when I wore a glitter backpack, glitter shoes and a glitter dress at once, the effect on the eye can be blinding. This is a remnant of the shimmering that marks us. According to comedian Ali Wong, postpartum women love glitter so much because they are dead on the inside. It’s funny because it’s true. But maybe it’s not true (the dead part, not the glitter). Maybe it’s only true from the position where materiality is regarded as a horror, the res extensa that must be stopped at all costs. And besides, the luxurious fantasy of pure immaterial being is simply not the position available to the postpartum, breastfeeding, glittering subject. It does nothing for us.

After giving birth, I became obsessed with browsing the “What to Expect” forum for August 2018 births (which is when my son was born). There are always multiple threads going about women who feel like they are going crazy. One such strawberrycookima23—postpartum women identify with the strangest things—wrote:

I forgot my name. I was at the register making a return at BuyBuyBaby, the guy asked for my name, and I totally blanked. Had to text my husband. Thankfully it happened at a baby store—he said it happens all the time! Haha ma liiiiife.

It is no surprise that pregnancy and motherhood collapse the autonomous Cartesian subject almost beyond recognition. But perhaps the postpartum experience should not be seen as a temporal prolapse in need of pelvic-floor therapy—the failure of women to be autonomous or “concocted”—but as an opening of a specific kind of bodily vulnerability, a sort of sexual orientation. Perhaps, that is, all that shimmering glitter is not a compensation for emptiness, but the embrace of the blinding nature of this sexuality, its desire not to attract but to deflect the light of reason away from itself. Instead of solving it away, let us enter and wander inside the Shimmer.

●

The European medieval mystic tradition is, in my opinion, much more useful as a guide for women who find themselves inside of the glitter juggernaut than What to Expect When You’re Expecting. To illuminate this numinous state of being, the glorious res extensa that is the postpartum body and sexuality, Hadewijch’s thirteenth-century Book of Visions should be on everyone’s baby-shower list.

Hadewijch, like many other mystics of the Middle Ages, experienced God through love and bodily desire. She encountered God not through the mind, as did Descartes (who attributed his visions to “exploding head syndrome”), but through the body. In her visions, Hadewijch can almost taste God on her tongue. Her writings are brimming with annihilating, enraptured visions in which she and God receive each other and become one. In one such titillating vision, God speaks to Hadewijch of their potential communion. Afterwards she writes:

The longing in which I then was cannot be expressed by any language or any person I know; and everything I can say about it would be unheard-of to all those who never apprehended Love as something to work for with desire, and whom Love has never acknowledged as hers.

Hers is a hot lust, verging on madness—to the point of perceived breaking of limbs and bursting of veins. At some point in a vision, a seraph visits Hadewijch and shows her the seals on the wings of Countenance, revealing to her seven gifts that are seven signs of love. But there is an eighth gift, she says, “the Divine Touch, giving fruition, which does away with everything that pertains to reason, so that the loved one becomes one with the beloved.” Hadewijch is touched by God and thus she exists.

There is no Cartesian doubt, no room for deductive reasoning, no “self,” really, in the female mystic saint tradition. Their desire is not just to caress the Cross with one’s lips, but to enter the bowels of Christ’s body and drown in his blood. It is driven by the physical, sexy and sexual, blasphemous conviction of becoming one with God. After drinking the blood of her Beloved and eating his flesh one Sunday, Hadewijch is overcome by another vision, in which she is “outwardly satisfied and fully transported”:

I saw him completely come to naught and so fade and all at once dissolve that I could no longer recognize or perceive him outside of me, and I could no longer distinguish him within me. Then it was to me as if we were one without difference.

After this communion, Hadewijch experiences herself as having melted away until nothing of herself remained, just God. The vision is titled “Oneness in the Eucharist.” It made me think of a recurring dream I had while breastfeeding. In this dream—or was it a mystical vision?—I felt I woke up half-eaten by my son. As if he were a snake consuming another creature, I was still alive, with my head already digesting in his dark stomach. I wish I had known of Hadewijch then, so I could have interpreted this paranoid nightmare as a form of jouissance at the expense of my annihilation—to take comfort in what the philosopher Julia Kristeva has called the “virginal maternal.” (Women, Kristeva claims, are confined to the “maternal” function, which grants them privileged access to divine revelation.)

Giving birth certainly can feel medieval. It’s not just about the pain, but ultimately it is about the pain. Women birthing in our secular society have been liberated from many stupid things, but through our liberation we are alienated from the relation between pain and the divine. We dull the pain and substitute the divine in us with the glory of buying pink plastic baby bullshit. But the epidural eventually wears off, and the plastic pieces never fully match the shape of the soul. In the mystic saint tradition that had its high point between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, women experienced their bodies—through their capacity to menstruate, birth and lactate—as uniquely connected to God. Medieval saints then further manipulated their bodies for spiritual ends—jumping into ovens and ice pools, mutilating their flesh and developing “holy anorexia,” refusing to eat anything other than the Eucharist. In the mystic tradition, the investment in pain is equal only to the investment in love—it is our embodied capacity to love that is the sign of the divine in us. The divine capacity to love is mirrored only by the love of a human mother—this is the true First Principle, it is that which makes cogito ergo sum possible. For mystics such as the anchorite Julian of Norwich, the first known woman to write in the English language, the somatization of pain could be at once mystical, erotic and maternal. Indeed, for her, God is a mother. The blurring of these categories is both the signature and the source of power of the female mystic’s voice, made even more striking by the fact that these medieval women were writing at a time when women had little voice and almost no power.

Like the paradox of the “virginal maternal”—being both a mother and a virgin—the unique sexuality of the postpartum experience is enabled by the doubling of the body at birth. Not only does the woman multiply in the production of a child—now a woman and a child—but her body itself doubles, temporarily carrying both the memory of the non-mother that was and the promise of the mother that will be. The non-mother self, in the process of her extinguishing, is in awe before the mother’s body, before its divine capacity to give and sustain life. She is both titillated and horrified by a vagina that is suddenly able to expand to the size of a watermelon, mesmerized by the swelling and draining of breasts, blinded by the sight of an internal organ—the human baby—now caressed by the mother’s adoring hand out in the world.

We are now at the center of the Shimmer. Lena is looking down into a cave in which she discovers one of her fellow scientists, Dr. Ventress. Ventress, it turns out, wanted to find the source of the Shimmer not in order to stop it, but to merge with it. At this point, a giant light penetrates her and she explodes into it, becoming one with the glitter. I imagine some mythic women in floral dresses who simply slide into motherhood, goddesses unbothered by the smell of poop, at home in any damp cave. These are the “naturals”: the mom on a transatlantic flight handling three small children, or the unwashed breastfeeding mom who says she wouldn’t mind “another one.” But then there are others, such as myself, profoundly confused by the poop and threatened by the pain. Women who, like Lena, are reluctant to lose themselves to the Shimmer, who may need the glitter to seep through the skin and enter the bloodstream, setting everything ablaze from the inside out, who want, too, to bear witness to the meteor shower inside of the expanding universe that is their own body, as they turn into ash. But who otherwise wish to make it out—to survive, in one form or another.

●

It’s been two years now and things are no longer shimmering the way they used to. I’m not sure when it happened exactly, when this border was crossed, when I actually became a mother. The other day, I ran into my mommy friend A9 and her now-toddler son. We had lost touch some time ago; our baby nap-time schedules no longer matched and there were no more cracked nipples to unite us. We exchanged awkward pleasantries. In fact, I told her, things were actually going great for me—I’d become more productive than ever in the last year with my dissertation. “I don’t really have needs anymore,” I said. “It’s kinda scary.” A9 smiled in a way I’ve never seen before, attentive and radiant, but I thought I could glimpse a shadow of that familiar blank stare appear over her otherwise well-rested, freckled face. As we parted, I suddenly noticed that her foot kept rocking a phantom stroller, a postpartum days’ habit that must have become automatic to her. I quickly averted my eyes, but in a flash, I was at once conscious of how much motherhood must have changed me too.

I remember myself as a very inward person, and giving birth and motherhood turned me inside out, making me material and exterior to myself. Caring for my son, I became so much in the world, like a machine. Is it shimmering less because I have exited the Shimmer? Or have I become my double, a kind of walking machine-relic, burnt out from the inside? Something has made it out, but I am not sure it is me.

Art credit: Lee Materazzi

There is a recent movie called Annihilation, where a group of women scientists are sent by the American government to travel inside of a mysterious and ominously expanding territory, enveloped by an iridescent cloud, that is referred to as “the Shimmer.” Prior to the expedition, this shimmering territory is viewed from a nearby military station post, where, despite all technological advancement, scientific knowledge is deemed insufficient to stop its spread. When the women scientists find themselves inside of this Shimmer, the conventional sense of time disappears and they are beguiled by a beautiful, wild nature—a nature that seems to penetrate their bodies. One of the women is eaten by a monstrous, mutant bear; another woman is mauled by a gargantuan alligator and later turns into a flowering tree. The boundaries between entities collapse: past and present, outside and inside, animal, plant and human. It is a grotesque jouissance, an orgasm of nature that exists inside the Shimmer. Traveling closer to the source of the mesmerizing glow, the protagonist, Lena, played by Natalie Portman, discovers herself in a sort of cave where she is penetrated by light that creates her double, leaving her as if burning into ash inside of this uterine space.

A general consensus exists among my mommy friends that this film is about the postpartum experience—which is not just an experience, but an introduction to a liminal form of life. In the early days of my transition to motherhood, I discovered my new species congregating by the community fountain in the center of my apartment compound in Manhattan’s East Village: blank-eyed and diaper-bagged bodies that had fulfilled their biological mission, they could be spotted eating bits of food found sticking to their eternal yoga pants, rocking a stroller with a robotic foot. The fountain’s water was always lit up with neon-purple lights, and there was always a flock of new moms with strollers walking for hours around its circumference, as if in a trance, while elderly people with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers sat on the surrounding benches, eating snacks. Fountain of oblivion, we called it. The sound of gushing water helped our babies fall asleep, while the moms were all collectively daydreaming of the next cup of coffee. When addressing each other, we were identified by our children’s ages, which were counted in days or weeks; meanwhile, people who previously called me by name, such as the hospital doctor, now suddenly referred to me as “mom.” I particularly connected with one mom, let’s call her A9, a former theology student, over our shared cracked-nipple woes. Once the fountain of oblivion did its magic, we would signal to each other by lifting one hand to the mouth, meaning that it was time for coffee. At the nearby coffee shop, we would take turns watching each other’s babies while we went to the bathroom. Gifting each other the opportunity to shit in solitude cemented our bond.

Does Annihilation’s Lena—doubled, her old self destroyed, a new one forged in the Shimmer’s core—make it out? This question was existential to A9 and me then. It had to do with the survival of our species.

My transition to motherhood had been accompanied by physical changes that made me identify with almost anything in the genre of sci-fi horror. Not only was my postpartum hair loss weaving a red carpet on the ground, but my skin became brown and ashen, peeling off my body as if I were an onion. After giving birth, time for me seemed to have warped through the prism of sleep deprivation and I often felt that I’d been abducted by aliens, then returned to earth—seemingly the same, but qualitatively a different person. When I was not peeling off of myself, I was leaking out of myself. There were the constant streams of milk; retaining urine, blood and other such things became such a challenge that I continued to wear an adult diaper for months after giving birth. I developed a spinal-fluid drip, which means that the fluid protecting my brain from bumping into the skull was draining down my spine, a condition that exacerbated the sensation of losing my mind. At some point in this journey, I encountered obstacles that required that I—or at least whatever remained of me—self-cannibalize, and so I consumed my own placenta after shredding it in a mixer with some strawberries. But simultaneously with all this scary body shit, there was a strange feeling of the numinous—a communion with the sacred. The boundary between my skin and the world was evaporating before my eyes. This feeling was dangerous and weirdly erotic—my body expanding and the world penetrating me as my sense of self was being annihilated by the merger.

●

Res extensa—the extension of matter into space. Writing on the cusp of the European Enlightenment, the French philosopher and scientist René Descartes separated the res extensa—which he used interchangeably with res corporea, the extension of the body—from the res cogitans, the mind. This was the basis of what is known in philosophy as dualism—the division between the mind and the body as separate entities. But Descartes did not view them as equals. While we have direct access to the contents of our minds, he argued, our bodies are compromised by their intimate implication in the realm of appearance and sensation. In fact, from this perspective, the body was not only separate from the mind but entirely unnecessary. For the existence of his mind, Descartes concluded, “There is no need of any place, nor does it depend on any material thing; so that this ‘me,’ that is to say the soul by which I am what I am, is entirely distinct from body.” Thus were planted the seeds of an idea that has remained ingrained in Western thinking today, despite all those hours of yoga: that the body cannot be truly known and ought not, therefore, to be fully trusted.

The position of the res cogitans is largely unattainable for women, at least when viewed from the perspective of subject formation in Western metaphysics. In the Western philosophical tradition, women have long been conflated with matter and space. For better or worse: matter (and materiality by extension) comes from the Latin mater, or mother. Aristotle, in The Generation of Animals, while discussing sexual difference and the generation of offspring, famously writes that “the male provides the form and the principle of movement. The female provides the body, in other words, the material.” Until the seventeenth century or so, it was widely accepted that the fetus was formed out of menstrual blood (as opposed to the egg), which Aristotle referred to as the “prime matter”—proto hyle. On this theory, without the “male” activating cause, i.e. the sperm, matter lacked the ability to “concoct” itself, and so would decay and leak out of the uterine receptacle. This inability to “concoct”—and the Chernobylesque horror of an infinitely expanding materiality—makes me think that contemporary postpartum experience continues to be within the bounds of the Aristotelian paradigm. Pregnancy is beautiful and all, but in the end, you are supposed to keep it together—to concoct.

According to the gynecologist, one should abstain from sex for two months after giving birth. Everything is very sensitive down there—and then there is always that chance that the wall between your asshole and your vagina will have collapsed, a condition called “pelvic organ prolapse.” Nonetheless, one is encouraged to be a good sport: things will get back to normal. All the new mommy forums and the “your day with a newborn” YouTube channels proclaim the mantra: two months no sex, six months for the abdominal muscles to heal, and then you are “back to normal.” But, after my firsthand experience, I am not so sure that women actually make it out of the shimmering space of the postpartum experience. More likely, they combust and prolapse in it, and it is not them but their doubles who emerge out of its haze. It is their doubles who greet you with “It’s going great!” when you eventually do meet for fucking brunch.

You can often recognize these doubles by their peculiar preference for all things glitter: glitter bags, glitter pens, glitter cell-phone covers. In some cases, such as when I wore a glitter backpack, glitter shoes and a glitter dress at once, the effect on the eye can be blinding. This is a remnant of the shimmering that marks us. According to comedian Ali Wong, postpartum women love glitter so much because they are dead on the inside. It’s funny because it’s true. But maybe it’s not true (the dead part, not the glitter). Maybe it’s only true from the position where materiality is regarded as a horror, the res extensa that must be stopped at all costs. And besides, the luxurious fantasy of pure immaterial being is simply not the position available to the postpartum, breastfeeding, glittering subject. It does nothing for us.

After giving birth, I became obsessed with browsing the “What to Expect” forum for August 2018 births (which is when my son was born). There are always multiple threads going about women who feel like they are going crazy. One such strawberrycookima23—postpartum women identify with the strangest things—wrote:

It is no surprise that pregnancy and motherhood collapse the autonomous Cartesian subject almost beyond recognition. But perhaps the postpartum experience should not be seen as a temporal prolapse in need of pelvic-floor therapy—the failure of women to be autonomous or “concocted”—but as an opening of a specific kind of bodily vulnerability, a sort of sexual orientation. Perhaps, that is, all that shimmering glitter is not a compensation for emptiness, but the embrace of the blinding nature of this sexuality, its desire not to attract but to deflect the light of reason away from itself. Instead of solving it away, let us enter and wander inside the Shimmer.

●

The European medieval mystic tradition is, in my opinion, much more useful as a guide for women who find themselves inside of the glitter juggernaut than What to Expect When You’re Expecting. To illuminate this numinous state of being, the glorious res extensa that is the postpartum body and sexuality, Hadewijch’s thirteenth-century Book of Visions should be on everyone’s baby-shower list.

Hadewijch, like many other mystics of the Middle Ages, experienced God through love and bodily desire. She encountered God not through the mind, as did Descartes (who attributed his visions to “exploding head syndrome”), but through the body. In her visions, Hadewijch can almost taste God on her tongue. Her writings are brimming with annihilating, enraptured visions in which she and God receive each other and become one. In one such titillating vision, God speaks to Hadewijch of their potential communion. Afterwards she writes:

Hers is a hot lust, verging on madness—to the point of perceived breaking of limbs and bursting of veins. At some point in a vision, a seraph visits Hadewijch and shows her the seals on the wings of Countenance, revealing to her seven gifts that are seven signs of love. But there is an eighth gift, she says, “the Divine Touch, giving fruition, which does away with everything that pertains to reason, so that the loved one becomes one with the beloved.” Hadewijch is touched by God and thus she exists.

There is no Cartesian doubt, no room for deductive reasoning, no “self,” really, in the female mystic saint tradition. Their desire is not just to caress the Cross with one’s lips, but to enter the bowels of Christ’s body and drown in his blood. It is driven by the physical, sexy and sexual, blasphemous conviction of becoming one with God. After drinking the blood of her Beloved and eating his flesh one Sunday, Hadewijch is overcome by another vision, in which she is “outwardly satisfied and fully transported”:

After this communion, Hadewijch experiences herself as having melted away until nothing of herself remained, just God. The vision is titled “Oneness in the Eucharist.” It made me think of a recurring dream I had while breastfeeding. In this dream—or was it a mystical vision?—I felt I woke up half-eaten by my son. As if he were a snake consuming another creature, I was still alive, with my head already digesting in his dark stomach. I wish I had known of Hadewijch then, so I could have interpreted this paranoid nightmare as a form of jouissance at the expense of my annihilation—to take comfort in what the philosopher Julia Kristeva has called the “virginal maternal.” (Women, Kristeva claims, are confined to the “maternal” function, which grants them privileged access to divine revelation.)

Giving birth certainly can feel medieval. It’s not just about the pain, but ultimately it is about the pain. Women birthing in our secular society have been liberated from many stupid things, but through our liberation we are alienated from the relation between pain and the divine. We dull the pain and substitute the divine in us with the glory of buying pink plastic baby bullshit. But the epidural eventually wears off, and the plastic pieces never fully match the shape of the soul. In the mystic saint tradition that had its high point between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, women experienced their bodies—through their capacity to menstruate, birth and lactate—as uniquely connected to God. Medieval saints then further manipulated their bodies for spiritual ends—jumping into ovens and ice pools, mutilating their flesh and developing “holy anorexia,” refusing to eat anything other than the Eucharist. In the mystic tradition, the investment in pain is equal only to the investment in love—it is our embodied capacity to love that is the sign of the divine in us. The divine capacity to love is mirrored only by the love of a human mother—this is the true First Principle, it is that which makes cogito ergo sum possible. For mystics such as the anchorite Julian of Norwich, the first known woman to write in the English language, the somatization of pain could be at once mystical, erotic and maternal. Indeed, for her, God is a mother. The blurring of these categories is both the signature and the source of power of the female mystic’s voice, made even more striking by the fact that these medieval women were writing at a time when women had little voice and almost no power.

Like the paradox of the “virginal maternal”—being both a mother and a virgin—the unique sexuality of the postpartum experience is enabled by the doubling of the body at birth. Not only does the woman multiply in the production of a child—now a woman and a child—but her body itself doubles, temporarily carrying both the memory of the non-mother that was and the promise of the mother that will be. The non-mother self, in the process of her extinguishing, is in awe before the mother’s body, before its divine capacity to give and sustain life. She is both titillated and horrified by a vagina that is suddenly able to expand to the size of a watermelon, mesmerized by the swelling and draining of breasts, blinded by the sight of an internal organ—the human baby—now caressed by the mother’s adoring hand out in the world.

We are now at the center of the Shimmer. Lena is looking down into a cave in which she discovers one of her fellow scientists, Dr. Ventress. Ventress, it turns out, wanted to find the source of the Shimmer not in order to stop it, but to merge with it. At this point, a giant light penetrates her and she explodes into it, becoming one with the glitter. I imagine some mythic women in floral dresses who simply slide into motherhood, goddesses unbothered by the smell of poop, at home in any damp cave. These are the “naturals”: the mom on a transatlantic flight handling three small children, or the unwashed breastfeeding mom who says she wouldn’t mind “another one.” But then there are others, such as myself, profoundly confused by the poop and threatened by the pain. Women who, like Lena, are reluctant to lose themselves to the Shimmer, who may need the glitter to seep through the skin and enter the bloodstream, setting everything ablaze from the inside out, who want, too, to bear witness to the meteor shower inside of the expanding universe that is their own body, as they turn into ash. But who otherwise wish to make it out—to survive, in one form or another.

●

It’s been two years now and things are no longer shimmering the way they used to. I’m not sure when it happened exactly, when this border was crossed, when I actually became a mother. The other day, I ran into my mommy friend A9 and her now-toddler son. We had lost touch some time ago; our baby nap-time schedules no longer matched and there were no more cracked nipples to unite us. We exchanged awkward pleasantries. In fact, I told her, things were actually going great for me—I’d become more productive than ever in the last year with my dissertation. “I don’t really have needs anymore,” I said. “It’s kinda scary.” A9 smiled in a way I’ve never seen before, attentive and radiant, but I thought I could glimpse a shadow of that familiar blank stare appear over her otherwise well-rested, freckled face. As we parted, I suddenly noticed that her foot kept rocking a phantom stroller, a postpartum days’ habit that must have become automatic to her. I quickly averted my eyes, but in a flash, I was at once conscious of how much motherhood must have changed me too.

I remember myself as a very inward person, and giving birth and motherhood turned me inside out, making me material and exterior to myself. Caring for my son, I became so much in the world, like a machine. Is it shimmering less because I have exited the Shimmer? Or have I become my double, a kind of walking machine-relic, burnt out from the inside? Something has made it out, but I am not sure it is me.

Art credit: Lee Materazzi

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.