Instead of looking at the trees, look at the person who looks at the trees.

—Timothy Morton, Ecology Without Nature

I remember shutting my eyes to hear the soft wind sigh in the fine fringe of wire-thin needles, gathered five to a bunch, soughing high overhead. I remember closing my eyes to the sky to feel the breeze off the lily-pad-skinned lake brushing across my lids, the bark biting against my back, the roots tossing beneath my thighs. I remember: leaning against the white pine, the one growing from the tip of the rocky point since before my great-great-grandfather bought the family land, lying with the pine to catch my breath before we laid my uncle to rest. I was there to ask what the fact of death meant, how to live with it, and I had brought with me a book—Henry David Thoreau’s Walden; or, Life in the Woods—that I hoped held answers. It was 2003.

●

Many of us, recently, have been turning to books about trees. Titles such as The Wild Trees, The Miracle of Trees, The Power of Trees, The Book of Trees, Seeing Trees, Ancient Trees, Wise Trees, Witness Tree, Trees of Life, Trees in Paradise, The Life and Love of Trees, The Social Life of Trees, The Long, Long Life of Trees, and two different books called, simply, The Tree. Titles like Oak, Ginkgo, Mahogany, Sequoia, Hemlock, Ponderosa, American Chestnut, White Pine, The Golden Spruce, Looking for Longleaf and Gods, Wasps, and Stranglers—a delightful read dedicated to the fig. There are histories: 196 of them published since 2000, according to the Forest History Society’s database. And the photo books, many galleries’ worth, enough to clutter acres of coffee tables. It is a fact that one could pass seasons skimming these stacks without ever grazing the covers of the recent novels and chapbooks and children’s stories, the field guides and scientific papers and online articles, all of them dedicated to the tree, all of them published in this new century, more of them coming every week.

Perhaps this windfall was foreordained, a prophecy put down in the past’s indelible dust: trees, wherever we have made a home beneath spreading limbs, trunk, crown and leaves, transfix. A pair of them, the Tree of Life and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, were supposed to have witnessed the fall of humans and the beginning of history. It was in the shade of a fig tree that Siddhartha found enlightenment, becoming the Buddha; for Hindus, it’s the living figure of Brahma the Creator, Shiva the Destroyer and Vishnu the Preserver, all braided together. The Great Tree of Peace—a white pine—was, for the Haudenosaunee, living proof of commonwealth and coexistence, while the Norse knew that the nine worlds of their cosmology were held together by an enormous ash called Yggdrasil. A hemisphere away, baobabs, those sylvan archives slung across sub-Saharan Africa, have been patiently accreting generations of human meaning for far longer than anyone can remember.

Perhaps we turn to trees because we are insecure, because we envy them their solidity (the biggest among them are the largest living things on earth), their resilience (the planet is home to more than sixty thousand species), their tenacious immortality—for even though they must, like all things, die, trees live more or less forever. An oak can thrive for hundreds of years (there’s one in England thought to have sheltered Robin Hood); a sequoia for ten times longer. Prometheus, a bristlecone pine, lived in the White Mountains of eastern Nevada for nearly five thousand years, the oldest known non-clonal tree in the world, until a researcher named Donald Currey cut it down in the name of science. The clonal trees, whose stems sprout from a single ancient root system, are all but permanent: there’s a Norway spruce in Sweden—Old Tjikko, it’s called—nearly ten thousand years old, a eucalyptus in Australia that might be three thousand years older, and a quaking aspen system of 47,000 genetically identical trees in Utah, known as Pando, that had already seen 65,000 years when the first humans arrived in North America. You can go visit it today.

There’s something reassuring about a tree, aged fifty years or fifty thousand, especially when times are uncertain. And ours are. Human-driven global warming, deforestation, desertification, a plague of plastics and the decimation of everything, from insects to polar bears, that many are calling the sixth great extinction: this is an era—the Anthropocene, the so-called age of humans—when nothing, not the weather, not the ocean, not the air, not the soil, is what it was. “Where are we?” we ask the trees, straining our ears, hoping for an answer.

●

These trees are magnificent, but even more magnificent is the sublime and moving space between them, as though with their growth it too increased.

—Rainer Maria Rilke, quoted in Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space

I sat beneath the pine, in that summer of my 23rd year, because it is the place where I have gone to sit and think ever since I was six. My family moved when I was a child, frequently; I’ve never known where I was from, never had a place that claimed me, except for the often-visited family land, where we lived for a brief, broke moment in 1986, a place that never changed its familiar smell of sunburnt pine needles and hay-scented fern and my grandmother’s camphored blankets, where the wind came through the trees hushing comfort, and the white pine, balanced on its point, offered peace—the unmoving axis about which my world revolved. It was the umbilicus connecting me to my past, to my family’s deep history and to the place where I met Thoreau, himself an under-pine-sitter and connection seeker: “Wherever I sat, there I might live, and the landscape radiated from me accordingly.”

●

In 2015, German forester Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries from a Secret World shot to the top of book lists worldwide on the promise of revelation. What Wohlleben claimed to have discovered is a variation on what myth has always known to be true: trees, like us, are sentient. They speak. And they are social. The difference is that Wohlleben, drawing on the work of biologists and foresters from throughout the U.S. and Europe, has the scientific data to prove it. Trees, he tells us, communicate through chemical scent, and through what, for the past twenty years, forest ecologists have been calling the “wood wide web,” a network of interconnected roots and fungi—“fiber-optic Internet cables,” he writes—that bring entire forests online.

Wohlleben’s hope was that one day “the language of trees will eventually be deciphered,” and that we would then be able to log in to the wood wide web, there to be taught how to live sustainably. But he only had to wait two years for David George Haskell’s celebrated The Songs of Trees: Stories from Nature’s Great Connectors(2017), which begins with the proposition that “living memories of trees, manifest in their songs, tell of life’s community, a net of relations.” Haskell, like Wohlleben, is a biologist, and he claims to translate sylvan into English. When he cocks his ear tree-ward he hears the same secret the trees whispered to Wohlleben: every one of us is connected materially to everything else. Everything is a “network,” a word that occurs almost four dozen times in 257 pages, and the network is everything:

Our ethic must therefore be one of belonging, an imperative made all the more urgent by the many ways that human actions are fraying, rewiring, and severing biological networks worldwide. To listen to trees, nature’s great connectors, is therefore to learn how to inhabit the relationships that give life its source, substance, and beauty.

It’s thrilling to find oneself privy to the sort of Kabbalistic knowledge that lays the world’s inner workings bare. Everything is connected, both Wohlleben and Haskell repeat throughout their books, and nature speaks the language of science. Yet what Wohlleben and Haskell have to tell us has never been a secret. Point your finger at nearly any influential American environmental thinker and you will discover their prose twines itself around a core of connection (a word which means to tie together). “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe,” wrote John Muir, father of the Sierra Club, in My First Summer in the Sierra (1911). The same insight, electrified for the machine age, arcs its way across Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac (1949) and its famous land ethic: all of life, which Leopold imagined as a network of “circuits,” is wired in series—cut just one electrical trace, and the entire mechanism goes dark. A few decades later, in The Unsettling of America (1977), the Kentucky agrarian and writer Wendell Berry wrote that life “is a network, a spherical network, by which each part is connected to every other part.”

Nor is the devotion to connection a peculiarity of American tree-huggers, for modern biological science itself grew from the desire for it, with the tree standing as desire’s root metaphor. Ernst Haeckel, the German scientist who coined the term “ecology” in 1866, dreamt of a science of relations, one he illustrated with a tree of life (an image stretching back at least five thousand years, to the ancient Akkadian empire), which he had inherited from Charles Darwin, who wrote: “The affinities of all the beings of the same class have sometimes been represented by a great tree. I believe this simile largely speaks the truth.”

These songs and secrets are not the trees’, no matter what their authors say; they are, instead, dreams hatched in biologists’ labs.

●

How could that cry be wind alone?

Something has snapped in two. Something has been lost

that won’t return in this life.

—Vievee Francis, “White Mountain”

I had brought the wrong book, that day in 2003. I remember sitting with Walden for a few hours, never finding what I was looking for, shelving it bitterly. I eventually returned to my tree on its point, my pine, with another of Thoreau’s books, The Maine Woods, in hand. “Think how stood the white-pine tree,” he wrote in the book’s opening pages, “its branches soughing with the four winds, and every individual needle trembling in the sunlight.”

The Maine Woods is a dead man’s book, published after Thoreau’s consumption had buried him: it rings with revelation, especially in the first essay, “Ktaadn,” in which Thoreau recounts his attempt to climb Maine’s highest mountain. The higher he ascends into the clouds, the more mystical his writing becomes—“It was a place for heathenism and superstitious rights,—to be inhabited by men nearer of kin to the rocks and to wild animals than we”—before slamming to earth with a force that fractures the essay: “Think of our life in nature,—daily to be shown matter, to come into contact with it,—rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! the solid earth! the actualworld! the common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? where are we?”

It wasn’t lost on me, who was looking for direction, that contact led Thoreau to come unfixed from material fact, to lose his bearings and return to himself.

●

The great promise of The Song of Trees is that Haskell has discovered something real, durable, preordained, natural—the network of life. But his central, acoustic metaphor is confused; the book isn’t about music, it’s about circuitry. Life, for Haskell, is an array built to transmit electrical stimuli, memory an arrangement of “biochemical architecture.” A similar confusion wrinkles the pages of The Hidden Life of Trees, whose chapter headings often read like an introductory civics text, with titles like “Social Security,” “United We Stand, Divided We Fall,” “Community Housing Projects” and “Street Kids.” We learn that trees practice a vaguely European social democracy (“whoever has an abundance … hands some over; whoever is running short gets help”), albeit one marked by the nationalist fears of the Brexit era. In a chapter called “Immigrants,” Wohlleben writes, “It’s dangerous when foreigners pop up that are genetically very similar to native species,” because miscegenation and extinction of the “native” is likely to occur: “The Japanese larch is just such a case.” And so on.

We can never know what it means to see the world through knotty eyes; trees will always be translations of our own human fantasies, and, as with every act of translation, something of the original cannot but be lost. In turning untamed roots and gnarled trunks into sleek circuits and polished planks in conservative platforms, Haskell and Wohlleben have simplified something strange and complex—the tree—into something immediately familiar, tame, and all too digitally human. At the same time, as translators often do, they have obscured their own, subjective work. Haskell and Wohlleben no longer keep company with the scenes they create, but rather stand outside of them, disconnected. What remains is the illusion of timeless sylvan wisdom.

The first law of ecology, wrote Barry Commoner in The Closing Circle(1971), one of environmentalism’s sacred texts, is that “everything is connected to everything else”: the same stuff coughing from my tailpipe causes your lung cancer and your child’s wheezing asthma. The cool blasting from your air conditioner melts the polar ice caps. Each hamburger or soy-based veggie dog we eat can be measured in acres of Amazonian deforestation, pounds of mutagenic pesticides, gallons of manure and urine. Our actions, connection reminds us, always have consequences.

Somewhere along the way, though, what began as an observation (everything is connected) evolved into an imperative (“only connect!”), a demand to acknowledge the world’s material unity, with the promise that environmental enlightenment will somehow follow, as if ethics is simply the mechanical practice of acquiring information.

But we connect through violence as well as care; we connect when we amble among the trees as well as when we clear-cut them into board-feet of profit. Hierarchy is a chain of connection strung vertically from the haves to the have-nots. “Everything is connected” is a fact, not an ethic; it has no meaning, and tells us nothing about how we should inhabit the world, simply that we do. If it implies responsibility, it is silent on what the nature of our relationship to the earth should be: Do we tread lightly? Or are we to take control?

●

My trees were being killed. They weren’t my trees.

… Oh yes,

I wanted the world to be wild again. I believed

I might hold weather in my hands

and mend it. The night was finite, or infinite.

—Cecily Parks, “When I Was Thoreau at Night”

On May 15, 2018, a freak tornado slapped into my family’s land, snapping limbs, stripping trunks and scattering trees like lawnmower-blown grass clippings. My old white pine, leaning out over open water, shallowly rooted in stony, sopping soil, didn’t stand a chance. I last saw my tree five years earlier, in the middle of a move that would take my wife, my young son and me half a continent west to a strange place with different trees. We had another son, a few years after arriving there, and I wondered: What, besides impressions, will I be able to give him of the tree that once anchored my life?

●

“The ‘control of nature,’” wrote Rachel Carson in the concluding paragraph of Silent Spring (1962), “is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man.” Earlier in the book, she had famously followed the facts along the connecting pathways that seemingly innocent chemicals, like DDT, took on their way to environmental crisis, showing how technological and scientific hubris led to pesticidal dead zones, the poisoned silence of the birds, bodily mutation, and organ failure. But Carson’s book is also a scathing cultural critique of the idea that knowledge is power—power, she knew, is the problem.

Our greatest scientific and technological breakthroughs were supposed to set us free from our earthly bonds, but instead are ending life as humankind has known it. This should be radically humiliating. And yet, if anything, rising temperatures have spawned a new breed of entrepreneurial confidence. Witness the environmental “thought leader” who promises to remake the entire Earth, if not the solar system, in our own image: the Elon Musks, who will fly us all to Mars; the Stewart Brands, who crow, “We are as gods and might as well get good at it”; the geo-engineers, terraformers and imagineers who would fill our oceans with iron filings, artificially whiten our clouds, or send enormous mirrors into space to reflect back the sun’s rays. Witness those who claim to know nature’s way and to speak its language—as if we can’t imagine any mode of inhabiting the earth other than one of mastery.

“In nature nothing exists alone,” wrote Carson. Though she never used the word, coexistence—not connection—is the idea around which her thinking begins to coalesce. It anticipates the work of eco-critic Timothy Morton, who has spent the last ten years (so far) spinning an ecological theory of coexistence, and who, like Carson, suggests that existing together isn’t the same thing as being connected. Instead, as he writes in Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence (2016), it is premised on unbridgeable, untranslatable, unknowable difference—“strangeness,” he calls it—between humans and the world. This gap is the native habitat of wonder, where the world surprises us with its beauty and unpredictability and suffering, where the world puts us in our rightful place of humility.

The web, whether of silicon or silk, is one of the preferred metaphors for connection. But it has rarely been noticed that a web is only occasionally a place for tying together. It is, instead, a thing made almost entirely of nothing, where nearly invisible strands span many feet of emptiness, strands which, if gathered together, would signify only slightly more than zero. To focus on the thread is to miss the web’s essence: a place for slipping past, for never catching hold; a place for passing alongside.

To self-consciously coexist is to attune oneself to these gaps, to the possibility that we might live alongside beings that are radically different from ourselves, but upon whom we nevertheless depend. Carson called this bundle of living difference “earth’s green mantle,” a boggling latticework of water, soil, chemical processes and buzzing life, which remained ultimately mysterious despite mountains of accumulated data. If connection implies similarity, responsibility, and control, coexistence asks for humility—a way, Morton writes, for us “to relax our grip” and learn to live with.

●

Sitting over words

very late I have heard a kind of whispered sighing

not far

like a night wind in pines or like the sea in the dark

the echo of everything that has ever

been spoken

still spinning its one syllable

between the earth and silence.

—W. S. Merwin, “Utterance”

That periodic white pine on its point: it wasn’t until I heard news of the tornado and asked my father to send me photos of the wreckage, until I received them via email and scanned my screen for survivors, that I realized. I had taken Walden into the woods fifteen years ago, lost in grief, desperate for reassurance that everything would be alright. But it wasn’t. My uncle was gone. There were no answers, and in my disappointment I blamed the book. In truth, the failing was mine. “I went to the woods,” go the words I wasn’t ready to read, “because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

●

Where are we?

“The trees will die,” wrote the journalist, author, and activist Bill McKibben in The End of Nature (1989), the first book for a popular audience about the meaning of global climate change. “Consider nothing more than that—just that the trees will die.”

It is now 2018, and the baobabs are dying; the sequoias are, too. The Psalms were wrong: Lebanon’s cedars break not by the voice of the Lord but by the decree of Exxon-Mobil. Even Pando, which survived the last ice age, is falling sick. No matter how many terabytes of data the supercomputers crunch, it’s hard to know exactly how many trees will die in the coming years, how far forests will flee from their homes of today. The science is inconclusive, but the impression is clear. Landmarks fade. Connections come undone. We simply don’t know anymore where we are.

One dark night in 1954, Carson and her twenty-month-old grandnephew, Roger, whom she would adopt a few years later, went for a walk along the wild Maine coast. “It was clearly a time and place where great and elemental things prevailed,” she wrote. Carson described the experience in a short essay for Woman’s Home Companion called “Help Your Child to Wonder.” “I sincerely believe,” she wrote, that “it is not half so important to know as to feel.” Carson slips between wrack and water line, along that damp pause that is neither yet land nor sea, her grandnephew’s bundled vulnerable body clasped warmly against her own, the two of them together passing among rockweed and ghost crab and purple-shelled mussel, feeling their way, together, ecstatically, in the dark, among the living world.

If knowledge and power and control follow in the footsteps of connection, Carson’s coexistence encourages a recognition of our own ignorance and the other’s autonomy—which is a way of throwing us back on ourselves, critically and self-consciously. What can we really know about the wild world? How can we exist without diminishing life’s heterogeneity? What are we doing?

What’s most striking in Carson’s best writing is the way she embraces her own ignorance: fallible, impressible, self-aware and humble, all she has is herself. “Exploring nature with your child is largely a matter of becoming receptive to what lies all around you,” she writes. “It is learning again to use your eyes, ears, nostrils and fingertips, opening up the disused channels of sensory impression.” Becoming receptive to a world of which we are a part, and at the same time from which we are radically apart, is a way to let oneself be marked, and, in the marking, to discover that we live, and that we live alongside.

I wonder: What would it mean to contemplate a tree free of one’s pretensions to authority, to attune one’s humanity to its nature, to let it speak, rather than interrogate it for those secrets one already believes true? One might venture a question. The tree might hesitate, as they do in Richard Powers’s novel, The Overstory (2018)—“the trees refuse to say a thing.”

●

Isn’t everything, in the dark, too wonderful to be exact, and circumscribed? For instance, the white pine that stands by the lake.

—Mary Oliver, “White Pine”

The white pine is dead; the space between us has become absolute. But I’ve been marked. My eyes open wide, and still I hear and feel the breeze and the bark and the roots.

“It is said,” Thoreau wrote in his 1862 essay, “Walking,” upon which he worked as he lay dying, “that knowledge is power”:

Methinks there is … need of a Society for the Diffusion of Useful Ignorance, what we will call Beautiful Knowledge, a knowledge useful in a higher sense: for what is most of our boasted so-called knowledge but a conceit that we know something, which robs us of the advantage of our actual ignorance? … I do not know that this higher knowledge amounts to anything more definite than a novel and grand surprise on a sudden revelation of the insufficiency of all that we called Knowledge before—a discovery that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in our philosophy. It is the lighting up of the mist by the sun.

●

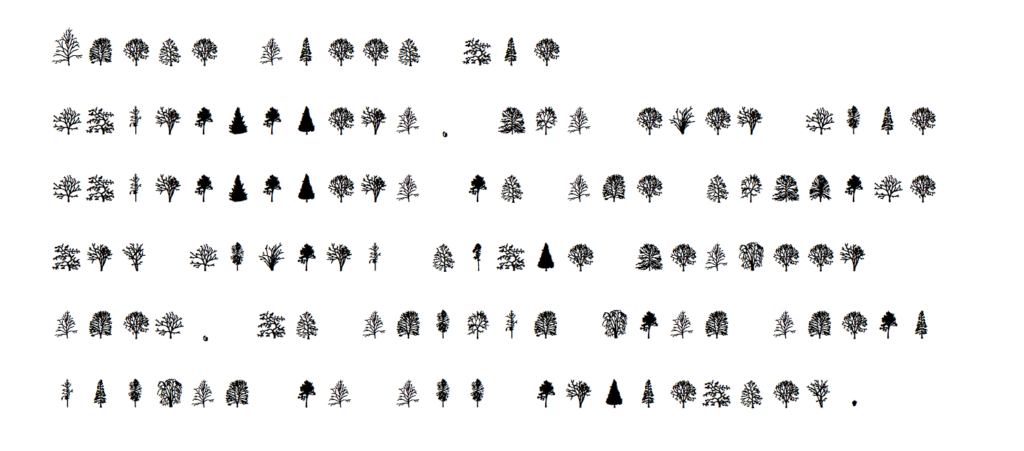

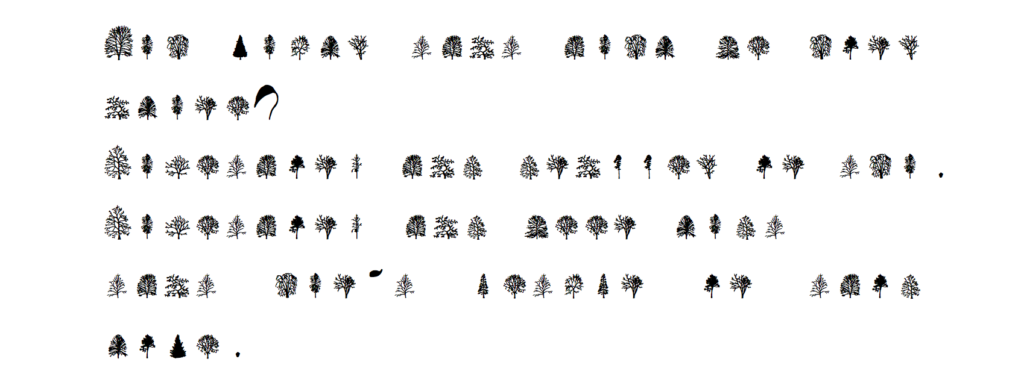

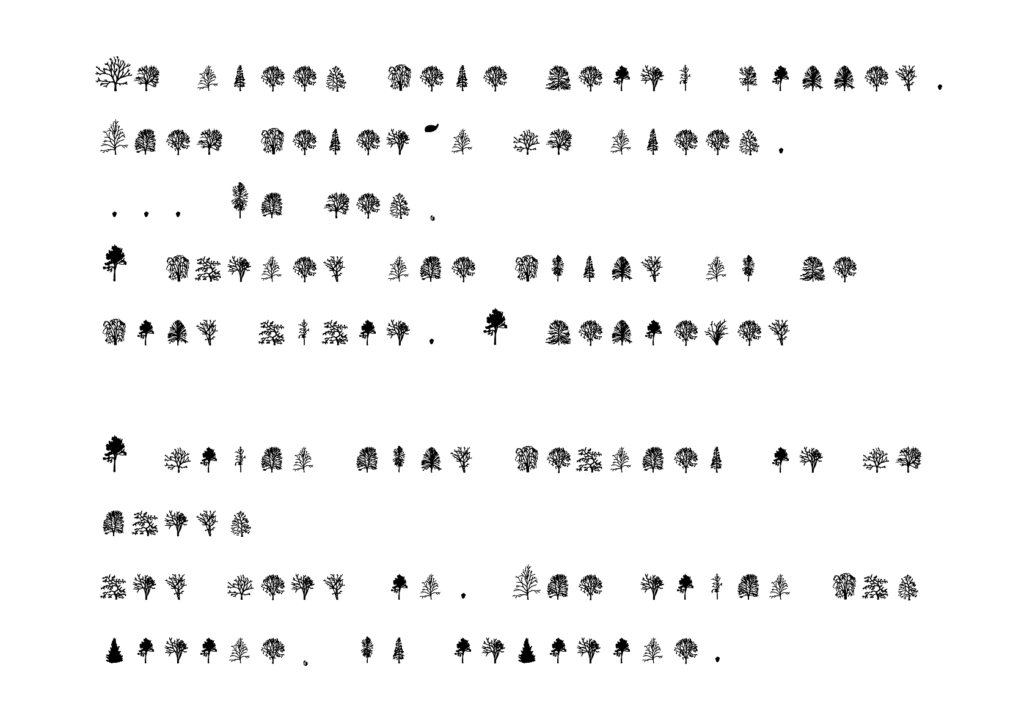

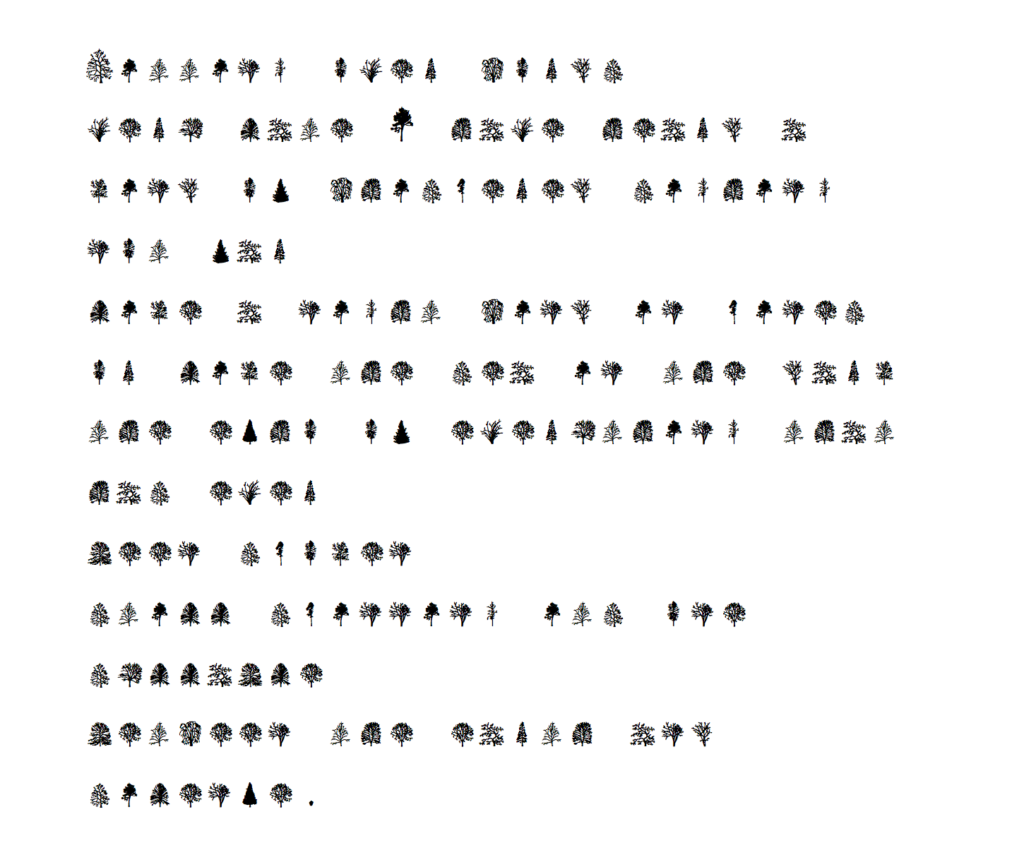

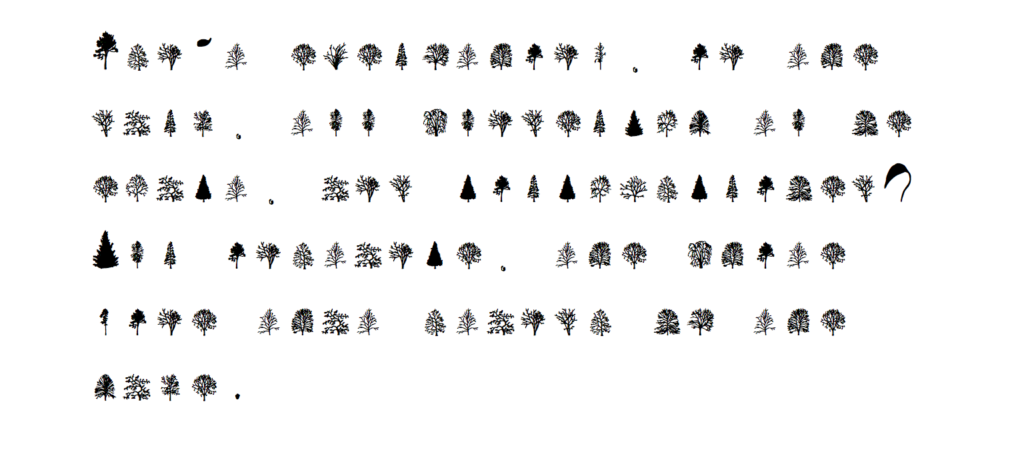

One day, when the angle of the sun lit up her world just right, I imagine that the artist Katie Holten saw something different when she looked at one of the trees growing along her New York City streets, or one of those growing in the park. “A dot. Ink buds. Twigs of reason. Branches of knowledge. Entangled thought-lines. I saw them all unfurl—letters germinating, sprouting, spreading forest-like across a blank page, then another.” I imagine Holten rushing back to her studio and there thoughtfully unfurling onto a crisp white sheet her masterwork: a wild typeface, one where each letter is a different species of tree. A, A, the image of an apple. B, B, a beech. An alphabetic forest of 26 trees ending with Z, Z, the zelkova. A forest, called About Trees, into which she invites her audience to wander. About Trees is spun simply. Holten weaves 51 excerpts from fifty authors who write about trees, from Borges’s “Funes, the Memorious”—“Funes not only remembered every leaf on every tree of every wood, but even every one of the times he had perceived or imagined it”—to Radiohead’s “Fake Plastic Trees,” and back again to “Funes, the Memorious”: “In fact, Funes remembered not only every leaf of every tree of every wood, but also every one of the times he had perceived or imagined it.”

It’s the sort of circularity that leaves you in a strange place. “Who speaks, and on behalf of whom?” Holten, the unreliable translator, writes. On the left of every page is a line—or hundreds of lines—of trees, neatly—or chaotically—ruled out. There’s some sort of governing logic, but it’s unclear what the design is until the reader flips to the right-hand page, which is the excerpt, in English: Zadie Smith or Robert Macfarlane, Darwin or Le Guin.

Holten has written out each excerpt in her tree font, all of the sylvan letters composing all of the words—2,402 of them in the case of Anna-Sophie Springer’s meditation on power, language and collecting, “Legere and βιβλιοθήκη: The Library as Idea and Space”—all of those words gathered onto a single page. The effect is bewildering. Lines toss in front of one’s eyes; there’s the nip of coherence, but not in the book’s point of connection: the knowledge that the “tree” font can be translated into English. Instead, it’s in the space that grows larger between the word and the estranged language—a space big enough to pass through, barely, and to emerge, with a rustling of leaves, changed. The coherence comes only when a reader, filled with his own sylvan memories, and Holten, filled with hers, and 49 others, some long dead, filled with forests of their own, and a strange-yet-intelligible font, and plain English all spend a moment passing through each other’s webs.

We turn to trees, as Holten knows, because that is what we’ve always done when we’re lost. But my tree is gone now, and I’m betting some of yours are too. Without them, we turn in vain. Or not. Perhaps, in the Anthropocene, this age of humans, we can turn back into our ignorant, humane, humble and receptive selves—can start again, among the stumps, close to the ground.

No one is sure whether the word “exist” comes originally from fourteenth-century French or is much older and Latin. But if it is of Latin extract, one of the word’s earliest meanings is “to rise from the dead.”

To coexist, then, means to rise up together.

For a selected bibliography, visit the author’s website.

Art credits: Plizzba (CC BY / Flickr) John Kittelsrud (CC BY / Flickr); Ernst Haeckel; Katie Holten (Tree font and image from About Trees)

I remember shutting my eyes to hear the soft wind sigh in the fine fringe of wire-thin needles, gathered five to a bunch, soughing high overhead. I remember closing my eyes to the sky to feel the breeze off the lily-pad-skinned lake brushing across my lids, the bark biting against my back, the roots tossing beneath my thighs. I remember: leaning against the white pine, the one growing from the tip of the rocky point since before my great-great-grandfather bought the family land, lying with the pine to catch my breath before we laid my uncle to rest. I was there to ask what the fact of death meant, how to live with it, and I had brought with me a book—Henry David Thoreau’s Walden; or, Life in the Woods—that I hoped held answers. It was 2003.

●

Many of us, recently, have been turning to books about trees. Titles such as The Wild Trees, The Miracle of Trees, The Power of Trees, The Book of Trees, Seeing Trees, Ancient Trees, Wise Trees, Witness Tree, Trees of Life, Trees in Paradise, The Life and Love of Trees, The Social Life of Trees, The Long, Long Life of Trees, and two different books called, simply, The Tree. Titles like Oak, Ginkgo, Mahogany, Sequoia, Hemlock, Ponderosa, American Chestnut, White Pine, The Golden Spruce, Looking for Longleaf and Gods, Wasps, and Stranglers—a delightful read dedicated to the fig. There are histories: 196 of them published since 2000, according to the Forest History Society’s database. And the photo books, many galleries’ worth, enough to clutter acres of coffee tables. It is a fact that one could pass seasons skimming these stacks without ever grazing the covers of the recent novels and chapbooks and children’s stories, the field guides and scientific papers and online articles, all of them dedicated to the tree, all of them published in this new century, more of them coming every week.

Perhaps this windfall was foreordained, a prophecy put down in the past’s indelible dust: trees, wherever we have made a home beneath spreading limbs, trunk, crown and leaves, transfix. A pair of them, the Tree of Life and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, were supposed to have witnessed the fall of humans and the beginning of history. It was in the shade of a fig tree that Siddhartha found enlightenment, becoming the Buddha; for Hindus, it’s the living figure of Brahma the Creator, Shiva the Destroyer and Vishnu the Preserver, all braided together. The Great Tree of Peace—a white pine—was, for the Haudenosaunee, living proof of commonwealth and coexistence, while the Norse knew that the nine worlds of their cosmology were held together by an enormous ash called Yggdrasil. A hemisphere away, baobabs, those sylvan archives slung across sub-Saharan Africa, have been patiently accreting generations of human meaning for far longer than anyone can remember.

Perhaps we turn to trees because we are insecure, because we envy them their solidity (the biggest among them are the largest living things on earth), their resilience (the planet is home to more than sixty thousand species), their tenacious immortality—for even though they must, like all things, die, trees live more or less forever. An oak can thrive for hundreds of years (there’s one in England thought to have sheltered Robin Hood); a sequoia for ten times longer. Prometheus, a bristlecone pine, lived in the White Mountains of eastern Nevada for nearly five thousand years, the oldest known non-clonal tree in the world, until a researcher named Donald Currey cut it down in the name of science. The clonal trees, whose stems sprout from a single ancient root system, are all but permanent: there’s a Norway spruce in Sweden—Old Tjikko, it’s called—nearly ten thousand years old, a eucalyptus in Australia that might be three thousand years older, and a quaking aspen system of 47,000 genetically identical trees in Utah, known as Pando, that had already seen 65,000 years when the first humans arrived in North America. You can go visit it today.

There’s something reassuring about a tree, aged fifty years or fifty thousand, especially when times are uncertain. And ours are. Human-driven global warming, deforestation, desertification, a plague of plastics and the decimation of everything, from insects to polar bears, that many are calling the sixth great extinction: this is an era—the Anthropocene, the so-called age of humans—when nothing, not the weather, not the ocean, not the air, not the soil, is what it was. “Where are we?” we ask the trees, straining our ears, hoping for an answer.

●

I sat beneath the pine, in that summer of my 23rd year, because it is the place where I have gone to sit and think ever since I was six. My family moved when I was a child, frequently; I’ve never known where I was from, never had a place that claimed me, except for the often-visited family land, where we lived for a brief, broke moment in 1986, a place that never changed its familiar smell of sunburnt pine needles and hay-scented fern and my grandmother’s camphored blankets, where the wind came through the trees hushing comfort, and the white pine, balanced on its point, offered peace—the unmoving axis about which my world revolved. It was the umbilicus connecting me to my past, to my family’s deep history and to the place where I met Thoreau, himself an under-pine-sitter and connection seeker: “Wherever I sat, there I might live, and the landscape radiated from me accordingly.”

●

In 2015, German forester Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries from a Secret World shot to the top of book lists worldwide on the promise of revelation. What Wohlleben claimed to have discovered is a variation on what myth has always known to be true: trees, like us, are sentient. They speak. And they are social. The difference is that Wohlleben, drawing on the work of biologists and foresters from throughout the U.S. and Europe, has the scientific data to prove it. Trees, he tells us, communicate through chemical scent, and through what, for the past twenty years, forest ecologists have been calling the “wood wide web,” a network of interconnected roots and fungi—“fiber-optic Internet cables,” he writes—that bring entire forests online.

Wohlleben’s hope was that one day “the language of trees will eventually be deciphered,” and that we would then be able to log in to the wood wide web, there to be taught how to live sustainably. But he only had to wait two years for David George Haskell’s celebrated The Songs of Trees: Stories from Nature’s Great Connectors(2017), which begins with the proposition that “living memories of trees, manifest in their songs, tell of life’s community, a net of relations.” Haskell, like Wohlleben, is a biologist, and he claims to translate sylvan into English. When he cocks his ear tree-ward he hears the same secret the trees whispered to Wohlleben: every one of us is connected materially to everything else. Everything is a “network,” a word that occurs almost four dozen times in 257 pages, and the network is everything:

It’s thrilling to find oneself privy to the sort of Kabbalistic knowledge that lays the world’s inner workings bare. Everything is connected, both Wohlleben and Haskell repeat throughout their books, and nature speaks the language of science. Yet what Wohlleben and Haskell have to tell us has never been a secret. Point your finger at nearly any influential American environmental thinker and you will discover their prose twines itself around a core of connection (a word which means to tie together). “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe,” wrote John Muir, father of the Sierra Club, in My First Summer in the Sierra (1911). The same insight, electrified for the machine age, arcs its way across Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac (1949) and its famous land ethic: all of life, which Leopold imagined as a network of “circuits,” is wired in series—cut just one electrical trace, and the entire mechanism goes dark. A few decades later, in The Unsettling of America (1977), the Kentucky agrarian and writer Wendell Berry wrote that life “is a network, a spherical network, by which each part is connected to every other part.”

Nor is the devotion to connection a peculiarity of American tree-huggers, for modern biological science itself grew from the desire for it, with the tree standing as desire’s root metaphor. Ernst Haeckel, the German scientist who coined the term “ecology” in 1866, dreamt of a science of relations, one he illustrated with a tree of life (an image stretching back at least five thousand years, to the ancient Akkadian empire), which he had inherited from Charles Darwin, who wrote: “The affinities of all the beings of the same class have sometimes been represented by a great tree. I believe this simile largely speaks the truth.”

These songs and secrets are not the trees’, no matter what their authors say; they are, instead, dreams hatched in biologists’ labs.

●

I had brought the wrong book, that day in 2003. I remember sitting with Walden for a few hours, never finding what I was looking for, shelving it bitterly. I eventually returned to my tree on its point, my pine, with another of Thoreau’s books, The Maine Woods, in hand. “Think how stood the white-pine tree,” he wrote in the book’s opening pages, “its branches soughing with the four winds, and every individual needle trembling in the sunlight.”

The Maine Woods is a dead man’s book, published after Thoreau’s consumption had buried him: it rings with revelation, especially in the first essay, “Ktaadn,” in which Thoreau recounts his attempt to climb Maine’s highest mountain. The higher he ascends into the clouds, the more mystical his writing becomes—“It was a place for heathenism and superstitious rights,—to be inhabited by men nearer of kin to the rocks and to wild animals than we”—before slamming to earth with a force that fractures the essay: “Think of our life in nature,—daily to be shown matter, to come into contact with it,—rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! the solid earth! the actualworld! the common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? where are we?”

It wasn’t lost on me, who was looking for direction, that contact led Thoreau to come unfixed from material fact, to lose his bearings and return to himself.

●

The great promise of The Song of Trees is that Haskell has discovered something real, durable, preordained, natural—the network of life. But his central, acoustic metaphor is confused; the book isn’t about music, it’s about circuitry. Life, for Haskell, is an array built to transmit electrical stimuli, memory an arrangement of “biochemical architecture.” A similar confusion wrinkles the pages of The Hidden Life of Trees, whose chapter headings often read like an introductory civics text, with titles like “Social Security,” “United We Stand, Divided We Fall,” “Community Housing Projects” and “Street Kids.” We learn that trees practice a vaguely European social democracy (“whoever has an abundance … hands some over; whoever is running short gets help”), albeit one marked by the nationalist fears of the Brexit era. In a chapter called “Immigrants,” Wohlleben writes, “It’s dangerous when foreigners pop up that are genetically very similar to native species,” because miscegenation and extinction of the “native” is likely to occur: “The Japanese larch is just such a case.” And so on.

We can never know what it means to see the world through knotty eyes; trees will always be translations of our own human fantasies, and, as with every act of translation, something of the original cannot but be lost. In turning untamed roots and gnarled trunks into sleek circuits and polished planks in conservative platforms, Haskell and Wohlleben have simplified something strange and complex—the tree—into something immediately familiar, tame, and all too digitally human. At the same time, as translators often do, they have obscured their own, subjective work. Haskell and Wohlleben no longer keep company with the scenes they create, but rather stand outside of them, disconnected. What remains is the illusion of timeless sylvan wisdom.

The first law of ecology, wrote Barry Commoner in The Closing Circle(1971), one of environmentalism’s sacred texts, is that “everything is connected to everything else”: the same stuff coughing from my tailpipe causes your lung cancer and your child’s wheezing asthma. The cool blasting from your air conditioner melts the polar ice caps. Each hamburger or soy-based veggie dog we eat can be measured in acres of Amazonian deforestation, pounds of mutagenic pesticides, gallons of manure and urine. Our actions, connection reminds us, always have consequences.

Somewhere along the way, though, what began as an observation (everything is connected) evolved into an imperative (“only connect!”), a demand to acknowledge the world’s material unity, with the promise that environmental enlightenment will somehow follow, as if ethics is simply the mechanical practice of acquiring information.

But we connect through violence as well as care; we connect when we amble among the trees as well as when we clear-cut them into board-feet of profit. Hierarchy is a chain of connection strung vertically from the haves to the have-nots. “Everything is connected” is a fact, not an ethic; it has no meaning, and tells us nothing about how we should inhabit the world, simply that we do. If it implies responsibility, it is silent on what the nature of our relationship to the earth should be: Do we tread lightly? Or are we to take control?

●

On May 15, 2018, a freak tornado slapped into my family’s land, snapping limbs, stripping trunks and scattering trees like lawnmower-blown grass clippings. My old white pine, leaning out over open water, shallowly rooted in stony, sopping soil, didn’t stand a chance. I last saw my tree five years earlier, in the middle of a move that would take my wife, my young son and me half a continent west to a strange place with different trees. We had another son, a few years after arriving there, and I wondered: What, besides impressions, will I be able to give him of the tree that once anchored my life?

●

“The ‘control of nature,’” wrote Rachel Carson in the concluding paragraph of Silent Spring (1962), “is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man.” Earlier in the book, she had famously followed the facts along the connecting pathways that seemingly innocent chemicals, like DDT, took on their way to environmental crisis, showing how technological and scientific hubris led to pesticidal dead zones, the poisoned silence of the birds, bodily mutation, and organ failure. But Carson’s book is also a scathing cultural critique of the idea that knowledge is power—power, she knew, is the problem.

Our greatest scientific and technological breakthroughs were supposed to set us free from our earthly bonds, but instead are ending life as humankind has known it. This should be radically humiliating. And yet, if anything, rising temperatures have spawned a new breed of entrepreneurial confidence. Witness the environmental “thought leader” who promises to remake the entire Earth, if not the solar system, in our own image: the Elon Musks, who will fly us all to Mars; the Stewart Brands, who crow, “We are as gods and might as well get good at it”; the geo-engineers, terraformers and imagineers who would fill our oceans with iron filings, artificially whiten our clouds, or send enormous mirrors into space to reflect back the sun’s rays. Witness those who claim to know nature’s way and to speak its language—as if we can’t imagine any mode of inhabiting the earth other than one of mastery.

“In nature nothing exists alone,” wrote Carson. Though she never used the word, coexistence—not connection—is the idea around which her thinking begins to coalesce. It anticipates the work of eco-critic Timothy Morton, who has spent the last ten years (so far) spinning an ecological theory of coexistence, and who, like Carson, suggests that existing together isn’t the same thing as being connected. Instead, as he writes in Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence (2016), it is premised on unbridgeable, untranslatable, unknowable difference—“strangeness,” he calls it—between humans and the world. This gap is the native habitat of wonder, where the world surprises us with its beauty and unpredictability and suffering, where the world puts us in our rightful place of humility.

The web, whether of silicon or silk, is one of the preferred metaphors for connection. But it has rarely been noticed that a web is only occasionally a place for tying together. It is, instead, a thing made almost entirely of nothing, where nearly invisible strands span many feet of emptiness, strands which, if gathered together, would signify only slightly more than zero. To focus on the thread is to miss the web’s essence: a place for slipping past, for never catching hold; a place for passing alongside.

To self-consciously coexist is to attune oneself to these gaps, to the possibility that we might live alongside beings that are radically different from ourselves, but upon whom we nevertheless depend. Carson called this bundle of living difference “earth’s green mantle,” a boggling latticework of water, soil, chemical processes and buzzing life, which remained ultimately mysterious despite mountains of accumulated data. If connection implies similarity, responsibility, and control, coexistence asks for humility—a way, Morton writes, for us “to relax our grip” and learn to live with.

●

That periodic white pine on its point: it wasn’t until I heard news of the tornado and asked my father to send me photos of the wreckage, until I received them via email and scanned my screen for survivors, that I realized. I had taken Walden into the woods fifteen years ago, lost in grief, desperate for reassurance that everything would be alright. But it wasn’t. My uncle was gone. There were no answers, and in my disappointment I blamed the book. In truth, the failing was mine. “I went to the woods,” go the words I wasn’t ready to read, “because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

●

Where are we?

“The trees will die,” wrote the journalist, author, and activist Bill McKibben in The End of Nature (1989), the first book for a popular audience about the meaning of global climate change. “Consider nothing more than that—just that the trees will die.”

It is now 2018, and the baobabs are dying; the sequoias are, too. The Psalms were wrong: Lebanon’s cedars break not by the voice of the Lord but by the decree of Exxon-Mobil. Even Pando, which survived the last ice age, is falling sick. No matter how many terabytes of data the supercomputers crunch, it’s hard to know exactly how many trees will die in the coming years, how far forests will flee from their homes of today. The science is inconclusive, but the impression is clear. Landmarks fade. Connections come undone. We simply don’t know anymore where we are.

One dark night in 1954, Carson and her twenty-month-old grandnephew, Roger, whom she would adopt a few years later, went for a walk along the wild Maine coast. “It was clearly a time and place where great and elemental things prevailed,” she wrote. Carson described the experience in a short essay for Woman’s Home Companion called “Help Your Child to Wonder.” “I sincerely believe,” she wrote, that “it is not half so important to know as to feel.” Carson slips between wrack and water line, along that damp pause that is neither yet land nor sea, her grandnephew’s bundled vulnerable body clasped warmly against her own, the two of them together passing among rockweed and ghost crab and purple-shelled mussel, feeling their way, together, ecstatically, in the dark, among the living world.

If knowledge and power and control follow in the footsteps of connection, Carson’s coexistence encourages a recognition of our own ignorance and the other’s autonomy—which is a way of throwing us back on ourselves, critically and self-consciously. What can we really know about the wild world? How can we exist without diminishing life’s heterogeneity? What are we doing?

What’s most striking in Carson’s best writing is the way she embraces her own ignorance: fallible, impressible, self-aware and humble, all she has is herself. “Exploring nature with your child is largely a matter of becoming receptive to what lies all around you,” she writes. “It is learning again to use your eyes, ears, nostrils and fingertips, opening up the disused channels of sensory impression.” Becoming receptive to a world of which we are a part, and at the same time from which we are radically apart, is a way to let oneself be marked, and, in the marking, to discover that we live, and that we live alongside.

I wonder: What would it mean to contemplate a tree free of one’s pretensions to authority, to attune one’s humanity to its nature, to let it speak, rather than interrogate it for those secrets one already believes true? One might venture a question. The tree might hesitate, as they do in Richard Powers’s novel, The Overstory (2018)—“the trees refuse to say a thing.”

●

The white pine is dead; the space between us has become absolute. But I’ve been marked. My eyes open wide, and still I hear and feel the breeze and the bark and the roots.

“It is said,” Thoreau wrote in his 1862 essay, “Walking,” upon which he worked as he lay dying, “that knowledge is power”:

●

One day, when the angle of the sun lit up her world just right, I imagine that the artist Katie Holten saw something different when she looked at one of the trees growing along her New York City streets, or one of those growing in the park. “A dot. Ink buds. Twigs of reason. Branches of knowledge. Entangled thought-lines. I saw them all unfurl—letters germinating, sprouting, spreading forest-like across a blank page, then another.” I imagine Holten rushing back to her studio and there thoughtfully unfurling onto a crisp white sheet her masterwork: a wild typeface, one where each letter is a different species of tree. A, A, the image of an apple. B, B, a beech. An alphabetic forest of 26 trees ending with Z, Z, the zelkova. A forest, called About Trees, into which she invites her audience to wander. About Trees is spun simply. Holten weaves 51 excerpts from fifty authors who write about trees, from Borges’s “Funes, the Memorious”—“Funes not only remembered every leaf on every tree of every wood, but even every one of the times he had perceived or imagined it”—to Radiohead’s “Fake Plastic Trees,” and back again to “Funes, the Memorious”: “In fact, Funes remembered not only every leaf of every tree of every wood, but also every one of the times he had perceived or imagined it.”

It’s the sort of circularity that leaves you in a strange place. “Who speaks, and on behalf of whom?” Holten, the unreliable translator, writes. On the left of every page is a line—or hundreds of lines—of trees, neatly—or chaotically—ruled out. There’s some sort of governing logic, but it’s unclear what the design is until the reader flips to the right-hand page, which is the excerpt, in English: Zadie Smith or Robert Macfarlane, Darwin or Le Guin.

Holten has written out each excerpt in her tree font, all of the sylvan letters composing all of the words—2,402 of them in the case of Anna-Sophie Springer’s meditation on power, language and collecting, “Legere and βιβλιοθήκη: The Library as Idea and Space”—all of those words gathered onto a single page. The effect is bewildering. Lines toss in front of one’s eyes; there’s the nip of coherence, but not in the book’s point of connection: the knowledge that the “tree” font can be translated into English. Instead, it’s in the space that grows larger between the word and the estranged language—a space big enough to pass through, barely, and to emerge, with a rustling of leaves, changed. The coherence comes only when a reader, filled with his own sylvan memories, and Holten, filled with hers, and 49 others, some long dead, filled with forests of their own, and a strange-yet-intelligible font, and plain English all spend a moment passing through each other’s webs.

We turn to trees, as Holten knows, because that is what we’ve always done when we’re lost. But my tree is gone now, and I’m betting some of yours are too. Without them, we turn in vain. Or not. Perhaps, in the Anthropocene, this age of humans, we can turn back into our ignorant, humane, humble and receptive selves—can start again, among the stumps, close to the ground.

No one is sure whether the word “exist” comes originally from fourteenth-century French or is much older and Latin. But if it is of Latin extract, one of the word’s earliest meanings is “to rise from the dead.”

To coexist, then, means to rise up together.

For a selected bibliography, visit the author’s website.

Art credits: Plizzba (CC BY / Flickr) John Kittelsrud (CC BY / Flickr); Ernst Haeckel; Katie Holten (Tree font and image from About Trees)

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.