In 1973, the poet Robert Creeley edited a paperback anthology of Walt Whitman’s selected verse. Midway through the introduction to the book, Creeley suggested a respect in which Leaves of Grass had “a very contemporary bearing for American poets”:

It is, moreover, a marked characteristic of American poetry since Whitman, and certainly of the contemporary, to have no single source for its language in the sense that it does not depend upon a “poetic” or literary vocabulary. … An American may choose, as John Ashbery once did, to write a group of poems whose words come entirely from the diction of the Wall Street Journal, but it is his own necessity, not that put upon him by some rigidity of literary taste.

That the American poet was distinctly guided by “his own necessity” rather than by an accepted set of literary standards was a powerful idea for certain mid-century poets and writers. It had a particular hold over the poets based at Black Mountain College, the wildly eclectic North Carolina art school where Creeley sporadically lived and taught between 1954 and 1955. The school would close only two years after he left. Chronically under-enrolled, under-staffed and under-funded, it canceled its last surviving classes near the end of 1956. Its last few years, however, produced a particularly ambitious attempt to define what a specifically American poetry could be.

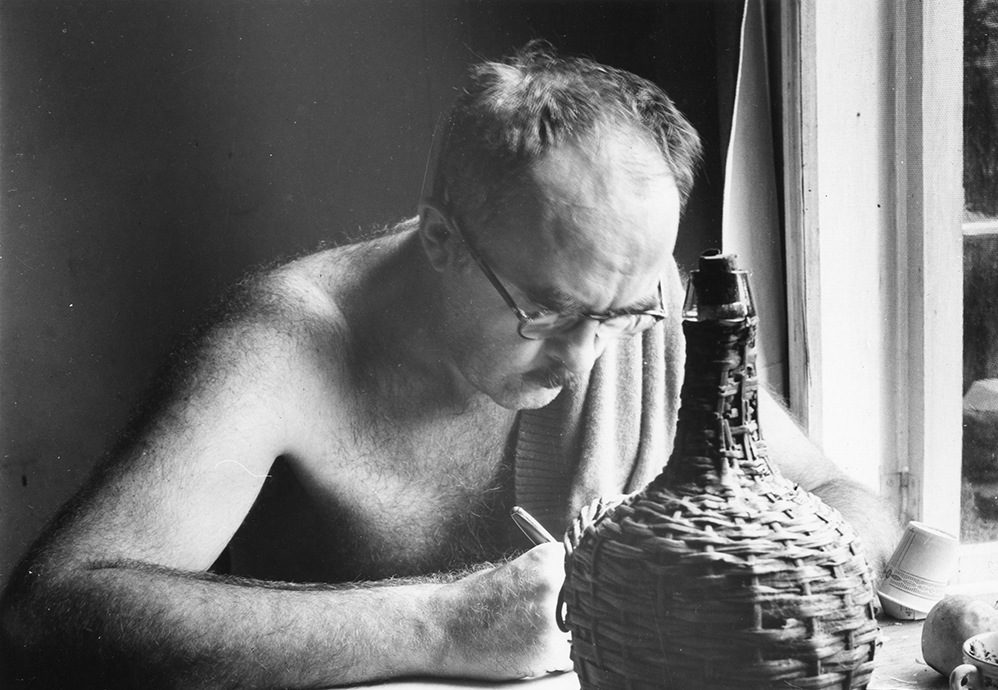

Creeley had grown up in Massachusetts, did a stint abroad in the American Field Service and took classes at Harvard, from which he never graduated. Beginning in 1950, he kept up a constant correspondence with Charles Olson, the fearsome, bullish poet sixteen years his senior who served as Black Mountain’s last rector and who finally lured Creeley to the school in 1954. (The letters the two poets exchanged between 1950 and 1952 fill ten volumes.) Olson was even more inclined than Creeley to make sweeping assertions about the American poet’s inheritance. “I take space to be the central fact to man born in America,” he wrote in the first lines of Call Me Ishmael, his strange and visionary early book about Melville. “I spell it large because it comes large here. Large, and without mercy.” For Olson, the prototypical American poet would have to be brawny enough to master the wide, merciless spaces that were his national habitat.

As one might imagine, the lines of thinking Creeley and Olson proposed at Black Mountain now seem alternately thrilling and dated, original and wrongheaded, brilliant and embarrassing. Is it even worth asking what a distinctly American poetry looks like? Posed like this, Olson and Creeley’s question bears a suspicious resemblance to those unhelpful definitional queries (e.g. In what does poetry consist? What are its essential features?) that Creeley’s favorite American poets rejected in favor of more practical questions about what could be done in a poem, how the English language could be used.

And yet the question still lurks around the periphery of much of today’s most interesting poetry. In her work since the late Seventies, Susan Howe has found more modest metaphors for the poet’s job than Olson and Creeley did (throughout The Birth-mark, her obsessively researched excavation of early American literature, she describes herself as a snooping “library cormorant”), but her books are still those of a writer self-consciously striving to define her peculiar and eccentric American inheritance. So too are recent collections by Cathy Park Hong (Engine Empire, the first section of which depicts a nineteenth-century mining expedition to California traveling across the Southwest); Adam Fitzgerald (the forthcoming George Washington, in which one poem ends on a description of the “Walt Whitman Shops,” a “shopping plaza, just down the road from the / poet’s birthplace”); and John Keene, who, like Howe, alternates between poetry and prose. (The most haunting passages in Keene’s prose collection Counternarratives, which includes a number of stories set in the pre-Civil War Americas, are monologues attributed to enslaved people of color, including a variation on the Jim of Huckleberry Finn.)

Looking back at the poets who flourished at Black Mountain, it’s striking both how seriously they set themselves the task of identifying the “marked characteristics of American poetry,” and how little their successors were to accept or replicate the characteristics they came up with. For later writers, the Black Mountain poets’ manner of asking about the “birthmark” of American poetry was both an important precedent and a point of departure.

●

Literature was not always a high priority at Black Mountain. Since its founding in 1933 by a small group of progressive educators who had been dismissed from Rollins College in Florida, the school had aspired to an educational vision based on what the painter Josef Albers—one of Black Mountain’s longest-serving faculty members—had articulated as the “belief that behavior and social adjustment are as interesting and important as knowledge … that the manual type, as well as eye or ear people, are as valuable as the intellectual type.” Black Mountain’s staff quarreled constantly over how this belief was to be interpreted. Usually, it was not understood to give “word people” the same attention as people whose gifts stayed concentrated in the eye or the ear. As late as 1948, the poet and potter M. C. Richards was writing two of her colleagues to complain about Albers’s insistence that “the only writing important to teach is grammar and punctuation.”

Within a decade Black Mountain had become an incubator for two towering books of postwar American poetry (Creeley’s For Love: Poems 1950 to 1960 and Olson’s The Maximus Poems); the primary base of operations for one of the most in influential poetry journals of the period (the Black Mountain Review); the name under which Donald Allen grouped a cluster of writers in his tastemaking anthology The New American Poetry; and a proving ground for two generations of young, gifted writers, from Hilda Morley and John Wieners to Ed Dorn, Joel Oppenheimer and Francine du Plessix Gray. Several figures had a part in this transformation. In addition to Creeley, there was Robert Duncan, the San Francisco-based poet who rarely stayed for long on campus but exercised a powerful influence over it from afar, particularly through his work on the Review. But the single biggest influence, most accounts agree, was Olson.

No sooner had Richards coaxed him to Black Mountain in 1951—he had already taught at two of the school’s legendary summer sessions, where his colleagues included Merce Cunningham and John Cage—than Olson started reshaping the college into a workshop for the execution of his idiosyncratic American poetic vision. He lectured, it’s said, with the same unremitting intensity on topics he knew well (Shakespeare; Melville; Pound) and ones in which he decidedly wasn’t an expert (theoretical physics; the ancient Mayans). For one of his classes, which he called “The Present,” the only assigned reading was each morning’s edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times and the New York Times. In workshops he ranted, bullied, castigated and heaped effusive praise.

It was as if he had spent so much time reading Moby-Dick and studying Melvilliana that he had started to embody the kind of American poetry he praised: muscular, dominating, Ahab-like. He had grown up in Worcester, Massachusetts to a Swedish father and a mother whose parents had emigrated from Ireland, and he came to think of his home state’s fishermen—furrowing and wresting a livelihood from the unhospitable sea—as models for what a poet could do with space. In The Maximus Poems, his epic song of praise to the Massachusetts fishing town of Gloucester, he imagined the blank page as an ocean it was his job to fish, till and populate. His lines zigzagged across the paper and met in violent intersections; he interspersed dense blocks of text with large swaths of white; he cut out excerpts from seventeenth-century fishing diaries and town logs and let them run for pages with his own light edits and interpolations.

Olson imagined an old America populated by strong, fertile Titans. Among the poem’s characters are “Ousoos the / hunter,” deemed “the first man / to carve out / the trunk / of a tree // and go out / on the waters / from the shore,” a group of pathbreaking “farmer giants … who poked / into the Caribbean or up Virginia creeks themselves,” and a cluster of “human beings” of whom it’s said, astonishingly, that “they filled the earth, the positiveness / was in their being, they listened // to the sententious, / with ears of the coil of the sea.” Reading those lines, you imagine Olson recalling another artifact of mid-century American literary brawn: Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, with its many coiled fishing lines, its sense of the ocean as an unmastered frontier and its frequent sententious utterances on the order of “pain does not matter to a man.” (Incidentally, for a few months during the winter of 1944-1945, Olson and his wife Connie had rented out the guest house on Hemingway’s Key West beach property, where the novelist’s former wife still lived with her sons. It was there, in a weird confusion of influences, that Olson discovered Pound, according to one of his later letters: “1st caught him, in Hemingway’s copy, of Personae, living in Hem’s swimming-house, K W, 1945.”)

For Olson, writing these myths was a way of paying tribute to the line of New England seamen that had begun with figures like John Smith and ended with his grandfather’s generation of Gloucester fishing people—“the last of the iron men.” The cycle was arranged to give the “respect … that belongs to what these men did, / and faced, to handle other men, / and direct their work.” Of these men Olson considered it “a testimonial, that they are still, or almost still, alive,” and

a pleasure to report,

to a city which is now so moribund,

that there are men still,

in some of these houses, of evenings,

who are of this make.

The Maximus Poems was also Olson’s way of insisting that he, too, was “of this make,” that he and the poets he lists in one poem near the end of the cycle—“John Wieners, / Edward Dorn & the women they love, / and Allen Ginsberg in some way at least,” and of course Creeley—could make out of words what their grandfathers had made out of wood and stone. “With some hope,” he prays in the same passage, “my own daughter … may / live in a World on an Earth like this one we / few American poets have / carved out of Nature and of God.”

Olson was not the first American poet to make such claims for himself. In Pope-ish rhyming couplets, the eighteenth-century preacher Mather Byles once imagined that America had, for ages, “a barbarous Desart stood” until “the first Ship the unpolish’d Letters bore / Thro’ the wide Ocean to the barb’rous Shore.” At the end of the same poem, he addressed a painter (“Pictorio”) as a kind of co-conspirator in the project of civilizing the New World: “And sudden, at our Word, new World’s arise … / Alike our Labour, and alike our Flame: / ’Tis thine to raise the Shape; ’tis mine to fix the Name.”

Melville himself helped circulate this vision of the American poet as founder and legislator of the new world. So, in a different register, did Ralph Waldo Emerson. “The poet is representative,” Emerson wrote in 1844. “He stands among partial men for the complete man, and apprises us not of his wealth, but of the common-wealth.” In the later essay “Uses of Great Men,” he listed the honors due to “representative” men in language that strikingly resembles the one Olson used for poets: “We call our children and our lands by their names. Their names are wrought into the verbs of language, their works and effigies are in our houses, and every circumstance of the day recalls an anecdote of them.”

With his 1950 manifesto “Projective Verse,” in which he chastised English-language poetry “from the late Elizabethans to Ezra Pound” for having been seduced by “the sweetness of meter and rime,” Olson was suggesting a kind of verse writing sufficiently flexible and expansive for the American poet’s manly, ground-clearing work. “That verse will only do,” he wrote then, “in which a poet manages to register both the acquisitions of his ear and the pressures of his breath.” This was Olson’s way of putting what Creeley would later argue in his introduction to Whitman: that American verse “does not depend upon a ‘poetic’ or literary vocabulary” as Victorian or Romantic verse relied on agreed-upon conventions of meter, syntax and rhyme. If the American poet was accountable to anything, for Olson, it was only lines and syllables—the “particles of sound” by which “words juxtapose in beauty.” Syllables were the wood from which the poet carved the ships that he’d sail across the page.

At Black Mountain, Olson suggested a model for translating this vision of American poetry into a system of living. It shouldn’t be surprising that the college was a freer, rambunctious, more sexually permissive place under Olson’s rectorship than it had been in the past. Black Mountain had coexisted with the conservative North Carolina communities around it in a kind of touchy détente, and its faculty had always squabbled over how much to concede to local values. (The question of whether or not to admit nonwhite students produced a particularly drawn-out, bitter debate.) In 1945, one of the school’s most influential faculty members, Bob Wunsch, had been forced out when it emerged that he was gay. By 1954, that prospect would have been inconceivable.

Freedom from the sweet constraints of “meter and rime” had become freedom from the old, aristocratic European mores that figures like Albers preserved. And just as Olson the poet made virtues out of strength, manliness and fertility, so Olson the rector turned Black Mountain into a space for male students to compete for dominance. Female students and faculty members were often diminished and cowed. In a fond but skeptical short essay about Olson, Francine du Plessix Gray remembered the bearlike poet “pressing his five fingers hard into my scalp until it hurt” to drive “the high-falootin’ Yurrup and poh-lee-tess” out of her head. Olson’s time at Black Mountain coincided with that of the composer Stefan Wolpe and his wife, the poet Hilda Morley, who never fully settled in. “If I happened to mention Henry James’s name with respect,” she later wrote about the group of male students she called “Olson’s boys,” “I was informed, mockingly, that this was—in one of Olson’s terms—only ‘literature.’”

●

For anyone surveying the work of the poets who studied under Olson, the question is why so little of it resembles the kind of writing one finds in The Maximus Poems. If Olson had hit on a distinctively American idiom for poetry—if, in Emerson’s words, his poetry was the kind of thing that gave him the right to “stand for the common-wealth”—why did his students and colleagues settle on poetics so different from his? Hilda Morley laid out her poems in elegant, wavy, tightly woven patterns that resembled DNA strands, as if in deliberate contrast to the crosscutting lattices of lines Olson strewed across the page. Ed Dorn’s comic Wild West-set epic poem Gunslinger, published in six parts between 1968 and 1975, seems just as much as The Maximus Poems to have come from an ear that—to borrow one of Olson’s pet phrases— “has the mind’s speed.” But its tone was more prankish than Olson’s, its vocabulary slangier and more colloquial, and its text full of the sorts of winking references to then-trendy books and philosophers that Olson would have sternly avoided. In “A Poem for Painters,” Olson’s student John Wieners offered an inventory of American place names that moves from west to east across the country, “over the Sierra Mountains,” “into Chicago,” and finally to “my city, Boston and the sea.” He could have been channeling Olson when he wrote that these names were “words / of works / we lay down for those men / who can come to them.” But Wieners mischievously includes Black Mountain as just one item midway through the list—a sly indication that the school didn’t have the last word over his style as a poet.

The poems that Creeley was writing during and after his time at Black Mountain, many of which were collected in For Love, are a useful reminder that even Olson’s closest associates often had their own ideas about what made American poetry distinctive. Rueful sketches of marriages in crisis and men running up against the limits of their physical and mental powers, Creeley’s fifties poems are no less about what it means, in his words, “to try to be a man,” than Olson’s. But where Olson’s poems are crowded with godlike models of virility and strength, Creeley’s center on male gures who venture into romantic relationships so waveringly that the grammar of their sentences sometimes seems on the verge of swooning and dissolving with them, as in the middle stanzas of “The Business”:

If you love

her how prove she

loves also, except that it

occurs, a remote chance on which you stake

yourself? …

You get the sense, reading these poems, that Creeley had absorbed Olson’s strong-arming, grandfatherly, self-assured tone and learned to deploy it selectively. In some instances, Creeley withheld that tone altogether, and the poems he produced in those moods are disarmingly vulnerable. You could imagine Olson bristling at the sight of his name in the dedication of a poem like “The Awakening,” which begins with a man who “feels small when he awakens” and ends with an address to an even frailer figure destined to “stumble breathlessly, on leg pins and crutch, / moving at all as all men, because you must.”

The great short poem “The Immoral Proposition,” which appeared alongside “The Awakening” in The New American Poetry, ends with a maxim that captures the tension in these poems between manly confidence and reflective self-doubt: “The unsure / egoist is not / good for himself.” Creeley’s poetry, like Olson’s, was loosely metered and closely linked to the rhythms of vernacular speech. Unlike Olson’s, however, it didn’t depend on the thought that the poet was “representative,” exceptional or even necessarily bold. In Creeley’s picture, American poets could be indecisive and frail; they could dither, gamble, nurture regrets and suffer pratfalls without the risk of losing their title.

●

In a recent review of Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Major Poetry, the critic Dan Chiasson insisted that Emerson’s own poetry was merely the “framework” that made possible “the wild synaptic activity of his protégés”—that is, of Whitman, whom Emerson mentored, and Dickinson, who read him attentively. “If Emerson’s poems had been just a little better than they were,” Chiasson concluded, “we might not have American literature as we know it. Our greatest writers, seeing their own visions usurped, might have been content to remain his readers.” Maybe, or maybe not; I suspect it would have taken more to silence Whitman than a marginally less schlocky version of Emerson’s “The Humble-Bee.” But a version of this argument seems to fit Olson. If Olson’s own vision of poetry had been less bullying, macho and aggrandized, he might not have so aggressively preached what turned out to be a liberating thought for generations of writers: that the American poet was free to model his verse after “the acquisitions of his ear” or “the pressures of his breath.”

For the generations of poets that succeeded Olson, that thought has been an encouragement to proceed with their own explorations—to draw on a wider range of dialects and patois; to incorporate new cultural, literary and political references; to accommodate parody and slang. In 1955, it’s safe to say, Olson never would have anticipated that his theories could inspire the production of a druggy epic poem that prominently features a talking horse named Claude Lévi-Strauss (Gunslinger). He certainly would not have expected that, fifty years after Black Mountain closed, Creeley’s call for a poetry that had “no single source for its language” would be answered by a book like Hong’s Dance Dance Revolution, a long narrative poem set in a futuristic city called “the Desert” and written in what one of its characters, in a prose foreword, calls “an amalgam of some three hundred languages and dialects,” particularly English, Spanish, Latin and Korean:

The language, while borrowing the inner structures of English grammar, also borrows from existing and extinct English dialects. Here, new faces pour in and civilian accents morph so quickly that their accents betray who they talked to that day rather than their cultural roots. Fluency is also a matter of opinion. There is no tuning fork to one’s twang.

Nor could he have predicted that one of his most sympathetic interpreters would identify as an explorer of card catalogues rather than of oceans or rivers. “To feed these essays,” Howe wrote in The Birth-mark, “I have dived through other people’s thoughts with footnotes for compasses and categories for quadrants.”

Olson’s genius at Black Mountain was for inspiring young poets to find their voices before that phrase became a cliché of writerly advice. He might never have guessed the voices that subsequent generations of American poets would find, and they differ too widely from his for him to “stand among” them as Emerson suggested—as the “complete man” of which they would give only partial impressions. But what he helped define as a value for poetry—registering the pressures of one’s own breath—turned out to be a remarkably flexible one. That later poets kept reimagining it in new and varied shapes proves only that the independent spirit Olson considered American poetry’s birthright was too strong for even a man of his make to control.

In 1973, the poet Robert Creeley edited a paperback anthology of Walt Whitman’s selected verse. Midway through the introduction to the book, Creeley suggested a respect in which Leaves of Grass had “a very contemporary bearing for American poets”:

That the American poet was distinctly guided by “his own necessity” rather than by an accepted set of literary standards was a powerful idea for certain mid-century poets and writers. It had a particular hold over the poets based at Black Mountain College, the wildly eclectic North Carolina art school where Creeley sporadically lived and taught between 1954 and 1955. The school would close only two years after he left. Chronically under-enrolled, under-staffed and under-funded, it canceled its last surviving classes near the end of 1956. Its last few years, however, produced a particularly ambitious attempt to define what a specifically American poetry could be.

Creeley had grown up in Massachusetts, did a stint abroad in the American Field Service and took classes at Harvard, from which he never graduated. Beginning in 1950, he kept up a constant correspondence with Charles Olson, the fearsome, bullish poet sixteen years his senior who served as Black Mountain’s last rector and who finally lured Creeley to the school in 1954. (The letters the two poets exchanged between 1950 and 1952 fill ten volumes.) Olson was even more inclined than Creeley to make sweeping assertions about the American poet’s inheritance. “I take space to be the central fact to man born in America,” he wrote in the first lines of Call Me Ishmael, his strange and visionary early book about Melville. “I spell it large because it comes large here. Large, and without mercy.” For Olson, the prototypical American poet would have to be brawny enough to master the wide, merciless spaces that were his national habitat.

As one might imagine, the lines of thinking Creeley and Olson proposed at Black Mountain now seem alternately thrilling and dated, original and wrongheaded, brilliant and embarrassing. Is it even worth asking what a distinctly American poetry looks like? Posed like this, Olson and Creeley’s question bears a suspicious resemblance to those unhelpful definitional queries (e.g. In what does poetry consist? What are its essential features?) that Creeley’s favorite American poets rejected in favor of more practical questions about what could be done in a poem, how the English language could be used.

And yet the question still lurks around the periphery of much of today’s most interesting poetry. In her work since the late Seventies, Susan Howe has found more modest metaphors for the poet’s job than Olson and Creeley did (throughout The Birth-mark, her obsessively researched excavation of early American literature, she describes herself as a snooping “library cormorant”), but her books are still those of a writer self-consciously striving to define her peculiar and eccentric American inheritance. So too are recent collections by Cathy Park Hong (Engine Empire, the first section of which depicts a nineteenth-century mining expedition to California traveling across the Southwest); Adam Fitzgerald (the forthcoming George Washington, in which one poem ends on a description of the “Walt Whitman Shops,” a “shopping plaza, just down the road from the / poet’s birthplace”); and John Keene, who, like Howe, alternates between poetry and prose. (The most haunting passages in Keene’s prose collection Counternarratives, which includes a number of stories set in the pre-Civil War Americas, are monologues attributed to enslaved people of color, including a variation on the Jim of Huckleberry Finn.)

Looking back at the poets who flourished at Black Mountain, it’s striking both how seriously they set themselves the task of identifying the “marked characteristics of American poetry,” and how little their successors were to accept or replicate the characteristics they came up with. For later writers, the Black Mountain poets’ manner of asking about the “birthmark” of American poetry was both an important precedent and a point of departure.

●

Literature was not always a high priority at Black Mountain. Since its founding in 1933 by a small group of progressive educators who had been dismissed from Rollins College in Florida, the school had aspired to an educational vision based on what the painter Josef Albers—one of Black Mountain’s longest-serving faculty members—had articulated as the “belief that behavior and social adjustment are as interesting and important as knowledge … that the manual type, as well as eye or ear people, are as valuable as the intellectual type.” Black Mountain’s staff quarreled constantly over how this belief was to be interpreted. Usually, it was not understood to give “word people” the same attention as people whose gifts stayed concentrated in the eye or the ear. As late as 1948, the poet and potter M. C. Richards was writing two of her colleagues to complain about Albers’s insistence that “the only writing important to teach is grammar and punctuation.”

Within a decade Black Mountain had become an incubator for two towering books of postwar American poetry (Creeley’s For Love: Poems 1950 to 1960 and Olson’s The Maximus Poems); the primary base of operations for one of the most in influential poetry journals of the period (the Black Mountain Review); the name under which Donald Allen grouped a cluster of writers in his tastemaking anthology The New American Poetry; and a proving ground for two generations of young, gifted writers, from Hilda Morley and John Wieners to Ed Dorn, Joel Oppenheimer and Francine du Plessix Gray. Several figures had a part in this transformation. In addition to Creeley, there was Robert Duncan, the San Francisco-based poet who rarely stayed for long on campus but exercised a powerful influence over it from afar, particularly through his work on the Review. But the single biggest influence, most accounts agree, was Olson.

No sooner had Richards coaxed him to Black Mountain in 1951—he had already taught at two of the school’s legendary summer sessions, where his colleagues included Merce Cunningham and John Cage—than Olson started reshaping the college into a workshop for the execution of his idiosyncratic American poetic vision. He lectured, it’s said, with the same unremitting intensity on topics he knew well (Shakespeare; Melville; Pound) and ones in which he decidedly wasn’t an expert (theoretical physics; the ancient Mayans). For one of his classes, which he called “The Present,” the only assigned reading was each morning’s edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times and the New York Times. In workshops he ranted, bullied, castigated and heaped effusive praise.

It was as if he had spent so much time reading Moby-Dick and studying Melvilliana that he had started to embody the kind of American poetry he praised: muscular, dominating, Ahab-like. He had grown up in Worcester, Massachusetts to a Swedish father and a mother whose parents had emigrated from Ireland, and he came to think of his home state’s fishermen—furrowing and wresting a livelihood from the unhospitable sea—as models for what a poet could do with space. In The Maximus Poems, his epic song of praise to the Massachusetts fishing town of Gloucester, he imagined the blank page as an ocean it was his job to fish, till and populate. His lines zigzagged across the paper and met in violent intersections; he interspersed dense blocks of text with large swaths of white; he cut out excerpts from seventeenth-century fishing diaries and town logs and let them run for pages with his own light edits and interpolations.

Olson imagined an old America populated by strong, fertile Titans. Among the poem’s characters are “Ousoos the / hunter,” deemed “the first man / to carve out / the trunk / of a tree // and go out / on the waters / from the shore,” a group of pathbreaking “farmer giants … who poked / into the Caribbean or up Virginia creeks themselves,” and a cluster of “human beings” of whom it’s said, astonishingly, that “they filled the earth, the positiveness / was in their being, they listened // to the sententious, / with ears of the coil of the sea.” Reading those lines, you imagine Olson recalling another artifact of mid-century American literary brawn: Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, with its many coiled fishing lines, its sense of the ocean as an unmastered frontier and its frequent sententious utterances on the order of “pain does not matter to a man.” (Incidentally, for a few months during the winter of 1944-1945, Olson and his wife Connie had rented out the guest house on Hemingway’s Key West beach property, where the novelist’s former wife still lived with her sons. It was there, in a weird confusion of influences, that Olson discovered Pound, according to one of his later letters: “1st caught him, in Hemingway’s copy, of Personae, living in Hem’s swimming-house, K W, 1945.”)

For Olson, writing these myths was a way of paying tribute to the line of New England seamen that had begun with figures like John Smith and ended with his grandfather’s generation of Gloucester fishing people—“the last of the iron men.” The cycle was arranged to give the “respect … that belongs to what these men did, / and faced, to handle other men, / and direct their work.” Of these men Olson considered it “a testimonial, that they are still, or almost still, alive,” and

The Maximus Poems was also Olson’s way of insisting that he, too, was “of this make,” that he and the poets he lists in one poem near the end of the cycle—“John Wieners, / Edward Dorn & the women they love, / and Allen Ginsberg in some way at least,” and of course Creeley—could make out of words what their grandfathers had made out of wood and stone. “With some hope,” he prays in the same passage, “my own daughter … may / live in a World on an Earth like this one we / few American poets have / carved out of Nature and of God.”

Olson was not the first American poet to make such claims for himself. In Pope-ish rhyming couplets, the eighteenth-century preacher Mather Byles once imagined that America had, for ages, “a barbarous Desart stood” until “the first Ship the unpolish’d Letters bore / Thro’ the wide Ocean to the barb’rous Shore.” At the end of the same poem, he addressed a painter (“Pictorio”) as a kind of co-conspirator in the project of civilizing the New World: “And sudden, at our Word, new World’s arise … / Alike our Labour, and alike our Flame: / ’Tis thine to raise the Shape; ’tis mine to fix the Name.”

Melville himself helped circulate this vision of the American poet as founder and legislator of the new world. So, in a different register, did Ralph Waldo Emerson. “The poet is representative,” Emerson wrote in 1844. “He stands among partial men for the complete man, and apprises us not of his wealth, but of the common-wealth.” In the later essay “Uses of Great Men,” he listed the honors due to “representative” men in language that strikingly resembles the one Olson used for poets: “We call our children and our lands by their names. Their names are wrought into the verbs of language, their works and effigies are in our houses, and every circumstance of the day recalls an anecdote of them.”

With his 1950 manifesto “Projective Verse,” in which he chastised English-language poetry “from the late Elizabethans to Ezra Pound” for having been seduced by “the sweetness of meter and rime,” Olson was suggesting a kind of verse writing sufficiently flexible and expansive for the American poet’s manly, ground-clearing work. “That verse will only do,” he wrote then, “in which a poet manages to register both the acquisitions of his ear and the pressures of his breath.” This was Olson’s way of putting what Creeley would later argue in his introduction to Whitman: that American verse “does not depend upon a ‘poetic’ or literary vocabulary” as Victorian or Romantic verse relied on agreed-upon conventions of meter, syntax and rhyme. If the American poet was accountable to anything, for Olson, it was only lines and syllables—the “particles of sound” by which “words juxtapose in beauty.” Syllables were the wood from which the poet carved the ships that he’d sail across the page.

At Black Mountain, Olson suggested a model for translating this vision of American poetry into a system of living. It shouldn’t be surprising that the college was a freer, rambunctious, more sexually permissive place under Olson’s rectorship than it had been in the past. Black Mountain had coexisted with the conservative North Carolina communities around it in a kind of touchy détente, and its faculty had always squabbled over how much to concede to local values. (The question of whether or not to admit nonwhite students produced a particularly drawn-out, bitter debate.) In 1945, one of the school’s most influential faculty members, Bob Wunsch, had been forced out when it emerged that he was gay. By 1954, that prospect would have been inconceivable.

Freedom from the sweet constraints of “meter and rime” had become freedom from the old, aristocratic European mores that figures like Albers preserved. And just as Olson the poet made virtues out of strength, manliness and fertility, so Olson the rector turned Black Mountain into a space for male students to compete for dominance. Female students and faculty members were often diminished and cowed. In a fond but skeptical short essay about Olson, Francine du Plessix Gray remembered the bearlike poet “pressing his five fingers hard into my scalp until it hurt” to drive “the high-falootin’ Yurrup and poh-lee-tess” out of her head. Olson’s time at Black Mountain coincided with that of the composer Stefan Wolpe and his wife, the poet Hilda Morley, who never fully settled in. “If I happened to mention Henry James’s name with respect,” she later wrote about the group of male students she called “Olson’s boys,” “I was informed, mockingly, that this was—in one of Olson’s terms—only ‘literature.’”

●

For anyone surveying the work of the poets who studied under Olson, the question is why so little of it resembles the kind of writing one finds in The Maximus Poems. If Olson had hit on a distinctively American idiom for poetry—if, in Emerson’s words, his poetry was the kind of thing that gave him the right to “stand for the common-wealth”—why did his students and colleagues settle on poetics so different from his? Hilda Morley laid out her poems in elegant, wavy, tightly woven patterns that resembled DNA strands, as if in deliberate contrast to the crosscutting lattices of lines Olson strewed across the page. Ed Dorn’s comic Wild West-set epic poem Gunslinger, published in six parts between 1968 and 1975, seems just as much as The Maximus Poems to have come from an ear that—to borrow one of Olson’s pet phrases— “has the mind’s speed.” But its tone was more prankish than Olson’s, its vocabulary slangier and more colloquial, and its text full of the sorts of winking references to then-trendy books and philosophers that Olson would have sternly avoided. In “A Poem for Painters,” Olson’s student John Wieners offered an inventory of American place names that moves from west to east across the country, “over the Sierra Mountains,” “into Chicago,” and finally to “my city, Boston and the sea.” He could have been channeling Olson when he wrote that these names were “words / of works / we lay down for those men / who can come to them.” But Wieners mischievously includes Black Mountain as just one item midway through the list—a sly indication that the school didn’t have the last word over his style as a poet.

The poems that Creeley was writing during and after his time at Black Mountain, many of which were collected in For Love, are a useful reminder that even Olson’s closest associates often had their own ideas about what made American poetry distinctive. Rueful sketches of marriages in crisis and men running up against the limits of their physical and mental powers, Creeley’s fifties poems are no less about what it means, in his words, “to try to be a man,” than Olson’s. But where Olson’s poems are crowded with godlike models of virility and strength, Creeley’s center on male gures who venture into romantic relationships so waveringly that the grammar of their sentences sometimes seems on the verge of swooning and dissolving with them, as in the middle stanzas of “The Business”:

You get the sense, reading these poems, that Creeley had absorbed Olson’s strong-arming, grandfatherly, self-assured tone and learned to deploy it selectively. In some instances, Creeley withheld that tone altogether, and the poems he produced in those moods are disarmingly vulnerable. You could imagine Olson bristling at the sight of his name in the dedication of a poem like “The Awakening,” which begins with a man who “feels small when he awakens” and ends with an address to an even frailer figure destined to “stumble breathlessly, on leg pins and crutch, / moving at all as all men, because you must.”

The great short poem “The Immoral Proposition,” which appeared alongside “The Awakening” in The New American Poetry, ends with a maxim that captures the tension in these poems between manly confidence and reflective self-doubt: “The unsure / egoist is not / good for himself.” Creeley’s poetry, like Olson’s, was loosely metered and closely linked to the rhythms of vernacular speech. Unlike Olson’s, however, it didn’t depend on the thought that the poet was “representative,” exceptional or even necessarily bold. In Creeley’s picture, American poets could be indecisive and frail; they could dither, gamble, nurture regrets and suffer pratfalls without the risk of losing their title.

●

In a recent review of Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Major Poetry, the critic Dan Chiasson insisted that Emerson’s own poetry was merely the “framework” that made possible “the wild synaptic activity of his protégés”—that is, of Whitman, whom Emerson mentored, and Dickinson, who read him attentively. “If Emerson’s poems had been just a little better than they were,” Chiasson concluded, “we might not have American literature as we know it. Our greatest writers, seeing their own visions usurped, might have been content to remain his readers.” Maybe, or maybe not; I suspect it would have taken more to silence Whitman than a marginally less schlocky version of Emerson’s “The Humble-Bee.” But a version of this argument seems to fit Olson. If Olson’s own vision of poetry had been less bullying, macho and aggrandized, he might not have so aggressively preached what turned out to be a liberating thought for generations of writers: that the American poet was free to model his verse after “the acquisitions of his ear” or “the pressures of his breath.”

For the generations of poets that succeeded Olson, that thought has been an encouragement to proceed with their own explorations—to draw on a wider range of dialects and patois; to incorporate new cultural, literary and political references; to accommodate parody and slang. In 1955, it’s safe to say, Olson never would have anticipated that his theories could inspire the production of a druggy epic poem that prominently features a talking horse named Claude Lévi-Strauss (Gunslinger). He certainly would not have expected that, fifty years after Black Mountain closed, Creeley’s call for a poetry that had “no single source for its language” would be answered by a book like Hong’s Dance Dance Revolution, a long narrative poem set in a futuristic city called “the Desert” and written in what one of its characters, in a prose foreword, calls “an amalgam of some three hundred languages and dialects,” particularly English, Spanish, Latin and Korean:

Nor could he have predicted that one of his most sympathetic interpreters would identify as an explorer of card catalogues rather than of oceans or rivers. “To feed these essays,” Howe wrote in The Birth-mark, “I have dived through other people’s thoughts with footnotes for compasses and categories for quadrants.”

Olson’s genius at Black Mountain was for inspiring young poets to find their voices before that phrase became a cliché of writerly advice. He might never have guessed the voices that subsequent generations of American poets would find, and they differ too widely from his for him to “stand among” them as Emerson suggested—as the “complete man” of which they would give only partial impressions. But what he helped define as a value for poetry—registering the pressures of one’s own breath—turned out to be a remarkably flexible one. That later poets kept reimagining it in new and varied shapes proves only that the independent spirit Olson considered American poetry’s birthright was too strong for even a man of his make to control.

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.