It was another day on the internet: a critic expressed her shock that the hit film Tár was not the true story she’d believed it to be. There is no Lydia Tár, and never was.

The ensuing ridicule was to be expected. The critic’s response encapsulated, however, exactly the way a decade of literary culture has taught audiences to receive the realist narrative arts. An implicit agreement has been forged between publishing houses and readers: the following events were experienced by someone, most usually the author herself. Google to corroborate; revel in the gossip; revolt if it’s made up.

In his 2010 manifesto, Reality Hunger, David Shields offered a controversial diagnosis for the sustained Anglophone allergy to invented fictions. “Our culture is obsessed with real events because we experience hardly any,” he wrote, alluding to the invented, “nonfictional” near-realities then proliferating on reality TV, regular TV, the lyric essay and the memoir. In such a world, novels become redundant: “Since to live is to make fiction, what need to disguise the world as another, alternate one?”

The novel survived this polemical and hotly debated attack. The suspicion of make-believe, however, lingers on in the way the reality-hungry novels (or films) of the 2020s are read and reviewed. The dominance of true-to-life literary composition and interpretation may be temporary, or it may be irreversible; recent dispatches from the academy proclaim that we live in a “postfictional” age. Whatever the case, extraliterary disciplines are hardly barred from picking up the slack where literature left off, nor is it clear that the impulse to invent reality has been universally put to rest across other fields. In a literary moment that has renounced the value of making things up, where does the human impulse toward invention find expression? One worrying, and increasingly probable, answer is finance.

●

It’s curious that fiction’s decoupling from what Shields called the “burden of unreality, the nasty fact that none of this ever really happened”—or what the German sociologist of economics Jens Beckert calls the “doubling of reality”—is simultaneous with financial markets’ embrace of the unreal. Especially since it wasn’t always this way. The story of these divergent literary and financial trends starts in the Eighties and Nineties, back when fiction was still fiction, and finance was still math.

In the decades leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, proponents of market deregulation used to argue that finance couldn’t be less like fiction. The infamous efficient-market hypothesis (EMH), based on advanced probability theory and particle physics, and formalized in 1965 by future Nobel Prize-winner Eugene Fama, was used to justify claims that new financial models computed unfailingly fair, accurate (i.e. “nonfictional”) asset prices. There was little need for regulatory intervention when prices were always “correct.” To the contrary, it was meddling with the free market’s ravenous, information-gathering mechanisms (a market’s ability to gather “perfect information” is a key assumption behind the EMH) that causes price swings and social harm.

After 2008, however, theorizations of the inherent irrationality and fictionality of markets returned to the fore. In his major critique of the 2008 collapse, Imagined Futures (2016), Beckert argued that the social role of markets is to act not as a ruthless and efficient computer (or, in EMH-speak, to ensure prices reflect “all available and pertinent information”), but to provide any predictions at all; in doing so, the market serves as a kind of collective omniscient narrator, corralling economic expectations toward potential outcomes that become likely insofar as many people anticipate them. Robert Shiller, one of three 2013 Nobel Prize winners in economics that year (that he shared the award with Fama reflects the field’s post-fin-crisis ideological split), echoed this concept in resurrecting the Keynesian idea of “animal spirits,” emotional noise that thwarts the predictive power of efficient-market models. From both of these perspectives, markets act less like perfectly efficient calculators than like fictions. They extrapolate the underlying, tangible, “real” economy into an expression of mass, and not always rational, psychology. They double reality. They operate according to the logic of guesswork and the suspension of disbelief, as well as fancy math. Sometimes, they act insane.

It’s worth remembering that all schools of economic thought hinge on large groups of people acting in concert “as if” certain assumptions about the future will hold: interest rates will rise or fall; mortgages will be repaid; the housing stock will increase or contract. (In planned economies, many of these assumptions come quite literally prix fixe.) What made the (ongoing) fictions of the financialized capitalism incubated in the early Aughts unique and uniquely dangerous is that they, like many realist novels, appeared to deny the fact that they were fictional. Unlike novels, they also claimed explanatory power over the real world. What were “collateralized debt obligations” padded with “mezzanine tranches” if not remarkable pieces of wordsmithing, treacherous castles in the air?

Meanwhile, as finance diverged structurally and rhetorically ever more from an adherence to the real, the critically acclaimed Anglophone novel became not only more truthful but more moralistic and stylistically austere. Forget your criminal fancy prose style, your Nabokovian maximalism, your abracadabra creation of value or event. Or maybe not just yet: “strict reportage,” Shields warned, “with its prohibition against invention, has its own aesthetically intolerable demands.”

Shields tried to avoid literary austerity measures by declaring all writing a fiction; as long as everything is invented, fiction blurring with non-, there’s no need to keep track of what is made up, nor flee from prose style suggestive of artifice. Voilà. By 2023, however, it is more common to argue that fiction doesn’t, or shouldn’t, exist. This is an altogether different assertion. The novels of the 2010s were exciting for flirting with the boundary between the novel and the non-novel, professing to be true while also being heavily fictionalized. This actually happened, the work of Rachel Cusk, Ben Lerner or Tao Lin insisted. (Though as Reality Hunger is fond of pointing out, even true stories necessarily misremember, rearrange, abstract and perform.) These novels captivated readers with their sophisticated relationship to the legerdemain of pretense. Or was the attraction rather that, unlike the traumatic, financialized avant-gardism that plunged the globe into recession, the underlying source material for these fictions professed a genuine referent in the real world, i.e. the author’s own lived experience? The 2020s are hungry for “reality,” one might amend Shields’s decade-old gambit, because thanks to the smoke and mirrors of financial markets, whose fictions so regularly crash into regular life, it has become harder and harder to grasp what “reality” even is.

It’s not a bad moral heuristic to compare your behavior to under-regulated financial markets and see if you’re doing the opposite. One wonders, however, what (if anything) is lost in the struggle against financialized capitalism when literature gives up on the capacity to “double reality,” or on inventive (even beautiful) language. The retreat from both style and fiction would appear to cede yet another mode of human expression to markets’ ever-expanding domain. What would it mean to steal the imagination back?

Three recent novels offer tentative answers to this question, most tantalizingly Martin Riker’s The Guest Lecture, an exuberant caper through the theory-stuffed imagination of a Keynesian economist. Boasting a premise as clever as anything since at least the last Percival Everett, Riker’s imaginative second novel is especially notable for its investigation of how economics uses (and abuses) the novel’s same rhetorical tools.

The book’s narrator-protagonist, Abby, is a feminist economics professor on a pressing deadline. A warm, fuzzy Keynesian (no efficient-market hypothesis or trading-floor pyrotechnics here), she has procrastinated on writing a lecture on Keynes himself. Lying awake in a hotel room the night before she’s to deliver her talk, still unsure what to say, she attempts to adopt the classical mnemonic device of assigning portions of her lecture to the rooms of a familiar building—in this case, her suburban, college-town home. It’s an ode to rhetoric, to Keynes (who appears, amusingly, as Abby’s imagined spirit guide and interlocutor), and it dramatizes how understanding markets as fiction can revitalize our own market critiques.

Or does it?

The main thrust of Abby’s lecture recalls Beckert, who also leans on Keynes, in particular Keynes’s assertion that in many cases, there is “no scientific basis on which to form any calculable probability whatever. … Nevertheless, the necessity for action and for decision compels us as practical men to do our best to overlook this awkward fact.” “There is, in other words, a rhetorical side to economics,” Abby rehearses, extending the thought. “Rhetorical not in the sense of a question that you’re not supposed to answer, but in the sense of belonging to the art of rhetoric, an art that economists, like most people, tend to look down upon—‘That’s all just rhetoric!’—as if rhetoric is some horrible thing.” The most enjoyable riffing on this observation is front-loaded in the opening, as Abby and Keynes set about pedantically establishing the premise. Setting off through the mnemonic rooms of Abby’s home, which in real life she shares with her do-gooder husband and adolescent daughter, she flubs a section of her digressive lecture in each. They begin on the porch, where Keynes kindly suggests she ought to begin her talk by, you know, introducing him. A fine—and funny—opening move.

Having started in on this nervy, apologetic register, however, The Guest Lecture never quite abandons it. The effect can be winningly comic: “Of course, when an economist tells you not to worry, you might worry all the more,” Abby says. “An economist’s ‘don’t worry’ usually means something bloodlessly calculated, like ‘worrying will increase the inclination to hoard currency and decrease spending on consumer goods.’” It’s a skillful bit of rhetoric unto itself; you’d expect a self-deprecating ethos from an economist appealing to a public that has turned against the dismal science. The impulse to apologize extends so deep, however, that Abby’s qualifications increasingly seem to serve a second purpose. Is the author likewise coaxing an imagined readership to stick around, lest they slam the book shut at the first mention of monetary policy—or worse, at the first suspicion that Abby isn’t concerned with social welfare? “When [Keynes] proposed that people not worry,” she continues, “it wasn’t to paper over the inequities of a system by which the rich come to control an ever-increasing percentage of the aggregate wealth while the poor are systematically disenfranchised. He was saying that he really didn’t think worrying was the right thing to do.” Again, this is amusing; Abby does nothing but worry. But it is also relentless. Later, the anxious qualification extends to her hand-wringing over personal consumer choices:

Are you really going to mourn your kitchen? That’s what you’re going to mourn?

One upside to living in the apocalypse is that it puts your problems into perspective.

It’s not just a kitchen, though. The kitchen is metonymic.

And also, yes, I am allowed to mourn my kitchen.

The Guest Lecture leaves the reader wondering how much of this anxious apologizing and self-critique is humorous characterization, a necessary extension of Abby’s rhetorical strategy, and how much is a hedge against a deeply distressed literary market—an echo of the author’s plea for the reader not to come to dislike her and her kitchen too much. Nor, for that matter, the author who invented her.

The familiar economic concept of “as if” behavior, in literary circles, is more commonly known as Coleridge’s “suspension of disbelief,” the basic price of admission into a fictional world. Yet as literature transforms itself under increasing market pressures to make a buck—and as literary fiction simultaneously buckles under pressure to be ever more “truthful” and authentic, to sell the author as much as the book—this concept has slowly been replaced by the idea of the reader-author “contract,” wherein participants in a reading transaction agree upon rules of exchange. Walk into any workshop and you will hear how, like financial contracts, the agreement between reader and writer can be undersigned and broken—how, like markets, underregulated fictions can collapse. As freewheeling finance acts more and more unapologetically like novels, it may be that novels themselves are being written more and more like traditional financial instruments—carefully designed to be safe readerly investments.

The Guest Lecture, as imaginative as it is sly, pulls up just short of a further revision of these contractual terms: the suspension of perceived political disagreement vis-à-vis the author’s imagined readership. Of course, at the other end of the spectrum, a novel written simply to goad or provoke falls into a similar trap; shock and apology can serve as two sides to the same coin, tossed up to appeal to market attention. Still, the fact that provocation can be its own kind of concession doesn’t make the apologetic tic any more aesthetically salvageable, especially in a moment when we’ve begun to apologize for novels being novels, for fiction being fiction, for writing the imagination at all. Surely there are more robust literary modes of resistance against totalizing market forces? Against the pervasive insistence that reality-doubling novels should be put to rest?

●

The British novelist Claire-Louise Bennett, whose working-class protagonists imagine their way not into economic utopias but fabulous manors, feasts and other decadent tableaus, is not much interested in risk management or readerly contracts. Seizing style and excess with zeal, her most recent novel, Checkout 19, arrives as a welcome reminder of the ways in which the imagination enables aesthetic, as well as political, ambitions. After a decade of literary discussion dominated by considerations of authenticity, morality and the “real,” it feels especially refreshing for inviting a long-neglected guest back to the table: beauty.

Since the publication of Pond in 2015, Bennett has been producing some of the most stylistically interesting, baroque and market-tone-deaf fiction in the Anglosphere. Praised for jettisoning narrative expectations, dinged for a bourgeois attention to domestic interiors and a lack of plot, generally heralded as a writer of lovely, if unclassifiable, autobiography-hungry monologues, Bennett’s work is also animated by class rage. The latter is most apparent in her latest novel, released in the U.S. last March. As with Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan series, Checkout 19 presents literature as both a handmaiden to class hierarchy as well as an escape route from working-class material conditions. It has been hailed above all (and despite Bennett’s so-frequent-as-to-be-distracting name-dropping of working-class writers like Ann Quin and Annie Ernaux) as an autofictional Künstlerroman.

And it is: Checkout 19 is the story, loosely speaking, of how our unnamed narrator-protagonist became a writer. The first part of the novel proceeds as a series of surreal, fantastical stories the protagonist once wrote to entertain herself while working overtime at a grocery (she’s stationed at checkout 19) in order to put herself through university, where she studied literature alongside far more privileged and prepared students. These stories she composes—and which we have the pleasure of reading, years later, in summary form, as our narrator struggles to recall her own oblique plots—are totally decadent, stylistically flamboyant, licentiously acquisitive in their endless lists of bourgeois comforts. Her imagination is stocked with preserved lemons, opera houses and encyclopedic collections of lace. These are magical stories. A girl spinning thread in a cellar spontaneously combusts. (On finishing the tale, the author herself is shocked: “And then the pen was done, spent, happy, and lay there now, smoldering on top of the closed exercise book. Spent, yes, but I knew now what it was capable of.”) A wealthy nobleman, a cross between a Borges and a Huysmans, curates a regal library in his palatial apartment, where reams of blank books contain a single sentence; when the library burns to the ground, this solitary phrase escapes as an anthropomorphic shadow. What fascinates the narrator above all is the sanctity of beauty, especially that found in books; what enrages her is all that conspires to keep her from accessing it, especially her economic conditions, compounded by others’ class condescension. One of the more provocative experiments of the book is whether her imagined realities (in particular, her decadent conjurings) are as real as reality itself:

Reality will right itself, roles must be resumed, and all things nice must take their place once more. Oh, and all things nice! Lace, opal, gypsophila, rose oil, meringue, gardenia, pearl powder, mink, sugared almonds, pas de chat, beeswax, tarot, orange blossom, Liszt, calisthenics, Venetian talc, parakeets, baklava, cameo, amber, calamine, broderie anglaise, whalebone, honeycomb, rabbit, polka, damask, potpourri, crystal, Chrétien de Troyes, lavender, mah-jong, gymkhana, tortoiseshell, squid ink, filigree, silk, saffron, liquorice, curling tongs, terrapins, vanilla pods, pineapples, bathwater, plumes, tinctures, tazze, candelabra, banana shampoo, maidenhair ferns, gold-plated taps, manicure sets, iced buns, tan tights, lapsang souchong, avocados, minty chocolate, the cherry moon—and what then, what then? … I enter the condiment aisle with a pen in my hand and my hair twisted back into a french plait on my way to checkout 19 where I will sit myself down upon a lopsided swivel chair and commence yet another nine-hour shift.

In both The Guest Lecture and Checkout 19, fantastical or absurdist plot elements are located explicitly in the narrator’s imagination; though it may seem unreal events occur, both are realism on a long psychological leash. Bennett more successfully explores the potential of this old trick of first recognizing the narrator has an imagination, then using it as the novel’s primary setting. (While Riker may have created the more impressive imaginary structure, the effect is undercut by the apologetic tone.) Tunneling into myriad worlds, Checkout 19 intentionally creates and destroys its own realms over and over, so that we begin to lose track of which one is “real.” This blurring distinguishes itself from market abuses of similar techniques through the self-consciousness of its own ambivalent power. The novel dramatizes both the dangers (the demotion of material experience) and potentials (generating test worlds) of “doubling reality” by toggling back and forth between the tangible and the projected.

It does so by inviting the imagination, fancy prose style and the fantastical back into fiction, freeing up a literary attitude capable of countering the “imagined futures” of financialized capitalism without denying the ways in which fiction is complicit in its logic. “We confused life with literature,” the narrator recalls of her student days,

and made the mistake of believing that everything going on around us was telling us something, something about our own little existences, our own undeveloped hearts, and, most crucially of all, about what was to come. What was to come? What was to come? We wanted to know, we wanted to know what lay ahead of us very very much, it was all we could think about and it was so unclear—yet at the same time it was all too clear.

The deep desire to reduce uncertainty, to predict the future, is the major reason, Beckert and Keynes would say, that markets exist. Novels rest easier in the ambiguity, and Checkout 19 makes us feel the poignant truth: uncertainty is unavoidable.

The pursuit of beauty, to which Bennett’s protagonist is so devoted, is subject to well-worn political critique. The philosopher Elaine Scarry provides a useful recap of the complaint in her famous 1998 essay On Beauty and Being Just. Those suspicious of beauty, she writes, often claim that “by preoccupying our attention, [it] distracts attention from wrong social arrangements,” leaving us “eventually indifferent” to injustice in the real world. As Checkout 19 progresses, we do begin to forget that these fantastical characters are make-believe, or that they don’t constitute the main storyline. The protagonist’s own reality seeps in around the edges: she’s broke; her alcoholic friend rapes her; she’s precariously housed. In a blast of rage at the end, more powerful for having been repressed for the better part of the novel, she finally finds a room of her own (she is a “visitor” in a rich woman’s house), where she reads of students from northern England who have “flattened” their accents in school for fear of ridicule: “It made our blood boil to read that. It made our blood boil. Imagine someone day in day out purposely making you feel ashamed of the sound of your own voice. Imagine what that would do to your confidence.” These are the material and class conditions in which our fantastical stories were made, and the drama of the novel hinges on the contrast.

That Bennett’s protagonist frequently writes so unapologetically for art for art’s sake is probably what led many outlets to overlook the novel’s concern for unjust social arrangements, instead celebrating Checkout 19 as a frothy, autofictional Künstlerroman. Again, it is—a fact crucial, however, to the way its frothy excesses generate an organizing mood of protest. One effect of the flamboyance is to upend any ambient elitism readers might bring to the book, for example the idea that working-class thinkers and stories are incompatible with aesthetic sensitivity or avant-garde ambition—that a novel isn’t a “working-class” story unless it’s full of grit and despair.

●

This reclamation of the aesthetic imagination for a working-class story echoes the psychological, surreal and subtly magical novels of prize-winning French writer Marie NDiaye, whose genre-defying work frequently marries formal ambition with class critique. The Cheffe: A Cook’s Novel, the English translation of which appeared in 2019, revolves (like Tár) around an eponymous, working-class female genius in a field dominated by men. (Also like Tár, it is not a true story.)

The Cheffe is a self-made culinary legend. Her prowess serves as a sly stand-in, however, for NDiaye’s arguments about the consumption and production of art across socioeconomic divides more generally. Told as a posthumous hagiography from the perspective of an obsessive and queasy-making former assistant (the narrator’s possessive adoration of the Cheffe borders on the lustful), conflicting views on her character and cooking proliferate. We begin to wonder: Who was the Cheffe, really? And to whom do her aesthetic sensibilities and achievements belong?

The daughter of laborers, brought up in poverty, the Cheffe faces a steady assault of class condescension from customers as she rises through the culinary ranks. But she is also capable of dishing it out herself. Wealthy clients are described like readers who, fed on fluff, are never satisfied, tiring “quickly even of dishes they loved, and their perpetual craving for new tastes grew stronger as they grew older.” By the same token, NDiaye hypnotically lampoons any patronizing praise:

People who knew of [the Cheffe’s] illiteracy and thought her simpleminded and so went into ecstasies over her culinary gifts, which they saw as the revelation of some unexpected, titillating sort of primal intelligence, always overlooked or underestimated her prodigious memory, thanks to which the Cheffe never needed written recipes or notes, she kept all her recipes meticulously archived in her head, she had the most methodical mind I’ve ever known.

The Cheffe turns out to be a true artist, the only one in the book, committed to punishing standards of artistic integrity. She shows outright disgust for kitschy, crowd-pleasing thrills: “Her cooking could be hard when you first encountered it, could be uncongenial, but once you’d learned to love it you felt only repugnance for any mannered, pandering cuisine, anything soft and creamy, you felt like that food didn’t think much of you, as if you were someone not much could be expected of … you don’t feel respected as a customer and an eater, you feel ashamed for the cook.” This conviction could generate its own flavor of elitism, though one suspects the Cheffe would simply call it good taste, a sensibility she considers readily available to all. She struggles to teach her extravagant clients to appreciate her subtlety while also keeping her haute cuisine affordable enough that any customer, of any background, “could approach without knowing anything about it, expecting nothing more than a full stomach.” She eschews “high-flown words” and “fancy talk.” She is an artist caught between aims of sophistication and republicanism that her immediate influences, at least, have declared to be in conflict.

NDiaye complicates Bennett’s celebration of aestheticism with broader questions of access. There are trade-offs, the novel (or at least its narrator) suggests. Though the Cheffe strives to create effortless, democratic dishes, the shifty narrator, also from a working-class background, remembers that his own mother considered her dishes food for “fairies or ogres,” and indeed “never even considered” that it was possible to walk into the restaurant “without having to prove she was a secret aristocrat, a fallen princess.” From this perspective, the Cheffe’s cuisine is “all fairytales, [my mother] didn’t believe in such things.” Warped as she is through the lens of the narrator, the Cheffe is also the stuff of fairy tales, the ambivalence of which Checkout 19 reminds us: embellishment can warp as well as reveal. There is no fairy-tale resolution of these tensions, and in NDiaye’s hands, the reader is meant to feel uncomfortable, even morally unmoored. Thrown into a small French town’s classist structure, the Cheffe’s enormous artistic talents seem to have a way of leaving everyone involved slightly ashamed and confused—except for the author, NDiaye herself.

Though the protagonists of The Cheffe and Checkout 19 take different approaches to beauty and the class codes that can encase it, they respond to similar socioeconomic and aesthetic pressures. To be either an “avant-garde” or “working-class” writer, Bennett’s narrator says of her own literary hero, the British novelist Ann Quin, “in addition to being a woman would have been sufficiently indecorous.” Yet to be both was “downright impudent, and incurred suspicion and snobbish disdain from some critics at the time.” Relentlessly acquisitive in her sensibilities, Bennett’s narrator claims all three traits—woman, avant-gardist, working-class—plus her lace, her Viennese opera houses, her rage. Because a good novelist, like a good cook, refuses to apologize for daring to make art.

●

In the end, literature’s reaction to financialized capitalism may not have been to abandon the imagination, but to embrace moral apology—including for the novel itself. It’s interesting, then, that it’s NDiaye’s The Cheffe, our French selection, that most fully explores these feelings of shame that can arise at the nexus of art, money and class. Though the novel refuses to apologize for itself, its characters are deeply unsure about where to source their dignity. The Cheffe’s bourgeois clients seek in her cuisine a reason to “stop hating what they were”; her parents, impoverished laborers, refuse her “excessively refined” gifts; the Cheffe herself is a paragon of American-style bootstrapping, though helpless to restrain her profligate daughter. (Then again, perhaps one expects no less of such a daughter, when her mother’s cooking is conceived “precisely to erase any memory of labor, of duress, of punishing hours.”) Is the Anglophone race toward reality-hungry fiction, its demotion of invented fairy tales and ogres, related to similarly complicated feelings of economic shame?

Judging from the literary criticism of the early 2020s, it would seem something ashamed and anxious is indeed at work. American critics Katy Waldman, Lauren Oyler, Becca Rothfeld and Christian Lorentzen have memorably declared contemporary realist, autobiography-hungry fiction to be handicapped by defensive “self-awareness,” “moral obviousness,” “sanctimony” and “careerism” in turn. It’s hard to disentangle these critiques from the writerly question of how to write fiction in a moment hyperaware of the gross and ever-expanding socio-economic injustices that financial markets, centered in New York and London, produce, and whose profiteering tentacles extend deep into Anglophone publishing. There is an enormous pressure to be part of the solution rather than part of the problem—and by extension, to value novels, like everything else, not for their truth or beauty but for their moral and economic use value.

It’s no mystery why Anglophone novelists take these pressures to heart: the wrong social arrangements are very wrong indeed. The United States and the United Kingdom represent the first and second most unequal of G7 nations. France, despite—and arguably because of—recent protests, is more equal, second only to Canada. In the wake of the financial crisis, America has not seen such a gross concentration of wealth in the hands of the top one percent since the 1920s. The slightly more equal U.K. still ranks among the most inequitable countries in all of Europe, with the top decile of British earners falling among the continent’s richest, while the bottom 20 percent of earners are 20 percent poorer than their French counterparts. Nor is it any mystery why, in the face of such economic injustice (and I include environmental injustice in this category), the pursuit of beauty over justice in fiction might begin to seem suspect. Beauty becomes ugly for appearing to ignore and distract from “wrong social arrangements,” as Elaine Scarry suggests, and even to broadcast indifference. As the urgency to rectify these arrangements grows, so does the pressure to apologize for the novel as a “mere” aesthetic object and experience. Short of abandoning the genre altogether, as Shields recommended in 2010, today a novel ought to help save the world. Or at the very least, to prove its use value beyond, and even instead of, the achievement of beauty or formal innovation. Above all, by being “real.”

This is all understandable. But it is also a shame. Taken to the extreme, it robs us of the vocabulary to discuss and celebrate beauty, one of the last escapes from market logic in the public sphere. This reflexive critique of beauty also seems to rest on a latent logical fallacy, namely that beauty and justice are mutually exclusive. There are myriad ways in which this assumption can be disproved, as Scarry set out to do in On Beauty and Being Just; she even goes so far as to argue the opposite, claiming that beauty in fact produces justice. It is enough for me, however, to restate what I hope Bennett and NDiaye have already made obvious: that concern for beauty and concern for justice can coexist in the same work of art.

To an Anglosphere by now accustomed to literary austerity, Bennett’s excesses feel particularly fresh. What I especially like about Checkout 19’s vocabulary for beauty is the way it so naturally allies itself with attitudes of abundance and renewability (as opposed to scarcity, austerity or apologetic retreat). That inexhaustibility and abundance are inscribed in beauty is something that strikes Scarry as well; though justice recedes from the world when we neglect to produce or create it, she points out, beauty endures in nature, ready-made, whether or not we pause to notice or care for it. Beautiful things thus have that hallmark of what Scarry calls a generous availability and what I would call a lack of self-consciousness. The impulse behind a beautiful thing—certainly behind the voice of all my favorite novels—seems it would go on existing even without an audience, in the same way a bird sings, or the sky clears, with indifference to praise or detraction; they can no more apologize for being beautiful than they can demand to be recognized as just. In a hyper-financialized moment obsessed with quantifying influence and impact, they unanxiously exist.

Millennia-long debates over the definitions of the beautiful and the hateful, good and evil, remain unresolved, so there’s little point in my trying to put a bow on things here. Instead I have a story I didn’t make up: a high-school dropout, intermittently homeless, a street fighter and drifter, as an adult teaches himself to read music and write poetry. A short composition he arranged for me on piano still hangs in my parents’ home. I used to play it as a girl. It is mediocre at best. My father once asked him why he did it. Why did he spend so many hours on poetry and music and literature when it was clear he had no talent? My grandfather replied that he was perfectly aware he was no Neruda, no Beethoven; he was no idiot. But he wanted to catch a glimpse—just a glimpse—of what it might have been like to be them. What arrogance! If you’re looking for an apology, you won’t find one here.

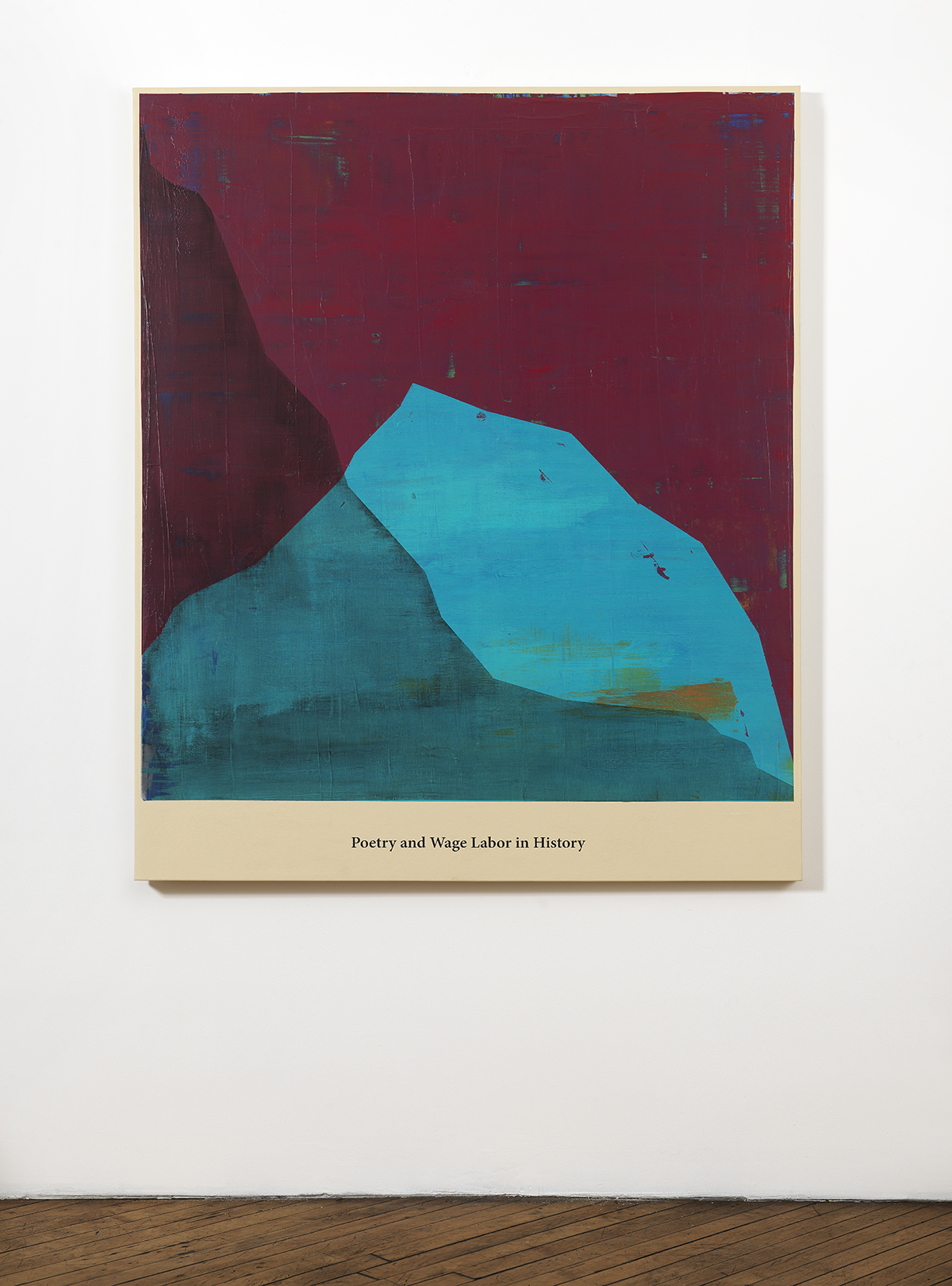

Art credit: (1) Danilo Correale, A spectacular miscalculation of global asymmetry #6, acrylic and oil on canvas, 60 × 50 in., 2017. Private collection, photo by D. Lasagni, (2) A spectacular miscalculation of global asymmetry #9, acrylic and oil on canvas, 36 × 30 in., 2017. Private collection, photo by D. Lasagni. All images courtesy of the artist.

It was another day on the internet: a critic expressed her shock that the hit film Tár was not the true story she’d believed it to be. There is no Lydia Tár, and never was.

The ensuing ridicule was to be expected. The critic’s response encapsulated, however, exactly the way a decade of literary culture has taught audiences to receive the realist narrative arts. An implicit agreement has been forged between publishing houses and readers: the following events were experienced by someone, most usually the author herself. Google to corroborate; revel in the gossip; revolt if it’s made up.

In his 2010 manifesto, Reality Hunger, David Shields offered a controversial diagnosis for the sustained Anglophone allergy to invented fictions. “Our culture is obsessed with real events because we experience hardly any,” he wrote, alluding to the invented, “nonfictional” near-realities then proliferating on reality TV, regular TV, the lyric essay and the memoir. In such a world, novels become redundant: “Since to live is to make fiction, what need to disguise the world as another, alternate one?”

The novel survived this polemical and hotly debated attack. The suspicion of make-believe, however, lingers on in the way the reality-hungry novels (or films) of the 2020s are read and reviewed. The dominance of true-to-life literary composition and interpretation may be temporary, or it may be irreversible; recent dispatches from the academy proclaim that we live in a “postfictional” age. Whatever the case, extraliterary disciplines are hardly barred from picking up the slack where literature left off, nor is it clear that the impulse to invent reality has been universally put to rest across other fields. In a literary moment that has renounced the value of making things up, where does the human impulse toward invention find expression? One worrying, and increasingly probable, answer is finance.

●

It’s curious that fiction’s decoupling from what Shields called the “burden of unreality, the nasty fact that none of this ever really happened”—or what the German sociologist of economics Jens Beckert calls the “doubling of reality”—is simultaneous with financial markets’ embrace of the unreal. Especially since it wasn’t always this way. The story of these divergent literary and financial trends starts in the Eighties and Nineties, back when fiction was still fiction, and finance was still math.

In the decades leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, proponents of market deregulation used to argue that finance couldn’t be less like fiction. The infamous efficient-market hypothesis (EMH), based on advanced probability theory and particle physics, and formalized in 1965 by future Nobel Prize-winner Eugene Fama, was used to justify claims that new financial models computed unfailingly fair, accurate (i.e. “nonfictional”) asset prices. There was little need for regulatory intervention when prices were always “correct.” To the contrary, it was meddling with the free market’s ravenous, information-gathering mechanisms (a market’s ability to gather “perfect information” is a key assumption behind the EMH) that causes price swings and social harm.

After 2008, however, theorizations of the inherent irrationality and fictionality of markets returned to the fore. In his major critique of the 2008 collapse, Imagined Futures (2016), Beckert argued that the social role of markets is to act not as a ruthless and efficient computer (or, in EMH-speak, to ensure prices reflect “all available and pertinent information”), but to provide any predictions at all; in doing so, the market serves as a kind of collective omniscient narrator, corralling economic expectations toward potential outcomes that become likely insofar as many people anticipate them. Robert Shiller, one of three 2013 Nobel Prize winners in economics that year (that he shared the award with Fama reflects the field’s post-fin-crisis ideological split), echoed this concept in resurrecting the Keynesian idea of “animal spirits,” emotional noise that thwarts the predictive power of efficient-market models. From both of these perspectives, markets act less like perfectly efficient calculators than like fictions. They extrapolate the underlying, tangible, “real” economy into an expression of mass, and not always rational, psychology. They double reality. They operate according to the logic of guesswork and the suspension of disbelief, as well as fancy math. Sometimes, they act insane.

It’s worth remembering that all schools of economic thought hinge on large groups of people acting in concert “as if” certain assumptions about the future will hold: interest rates will rise or fall; mortgages will be repaid; the housing stock will increase or contract. (In planned economies, many of these assumptions come quite literally prix fixe.) What made the (ongoing) fictions of the financialized capitalism incubated in the early Aughts unique and uniquely dangerous is that they, like many realist novels, appeared to deny the fact that they were fictional. Unlike novels, they also claimed explanatory power over the real world. What were “collateralized debt obligations” padded with “mezzanine tranches” if not remarkable pieces of wordsmithing, treacherous castles in the air?

Meanwhile, as finance diverged structurally and rhetorically ever more from an adherence to the real, the critically acclaimed Anglophone novel became not only more truthful but more moralistic and stylistically austere. Forget your criminal fancy prose style, your Nabokovian maximalism, your abracadabra creation of value or event. Or maybe not just yet: “strict reportage,” Shields warned, “with its prohibition against invention, has its own aesthetically intolerable demands.”

Shields tried to avoid literary austerity measures by declaring all writing a fiction; as long as everything is invented, fiction blurring with non-, there’s no need to keep track of what is made up, nor flee from prose style suggestive of artifice. Voilà. By 2023, however, it is more common to argue that fiction doesn’t, or shouldn’t, exist. This is an altogether different assertion. The novels of the 2010s were exciting for flirting with the boundary between the novel and the non-novel, professing to be true while also being heavily fictionalized. This actually happened, the work of Rachel Cusk, Ben Lerner or Tao Lin insisted. (Though as Reality Hunger is fond of pointing out, even true stories necessarily misremember, rearrange, abstract and perform.) These novels captivated readers with their sophisticated relationship to the legerdemain of pretense. Or was the attraction rather that, unlike the traumatic, financialized avant-gardism that plunged the globe into recession, the underlying source material for these fictions professed a genuine referent in the real world, i.e. the author’s own lived experience? The 2020s are hungry for “reality,” one might amend Shields’s decade-old gambit, because thanks to the smoke and mirrors of financial markets, whose fictions so regularly crash into regular life, it has become harder and harder to grasp what “reality” even is.

It’s not a bad moral heuristic to compare your behavior to under-regulated financial markets and see if you’re doing the opposite. One wonders, however, what (if anything) is lost in the struggle against financialized capitalism when literature gives up on the capacity to “double reality,” or on inventive (even beautiful) language. The retreat from both style and fiction would appear to cede yet another mode of human expression to markets’ ever-expanding domain. What would it mean to steal the imagination back?

Three recent novels offer tentative answers to this question, most tantalizingly Martin Riker’s The Guest Lecture, an exuberant caper through the theory-stuffed imagination of a Keynesian economist. Boasting a premise as clever as anything since at least the last Percival Everett, Riker’s imaginative second novel is especially notable for its investigation of how economics uses (and abuses) the novel’s same rhetorical tools.

The book’s narrator-protagonist, Abby, is a feminist economics professor on a pressing deadline. A warm, fuzzy Keynesian (no efficient-market hypothesis or trading-floor pyrotechnics here), she has procrastinated on writing a lecture on Keynes himself. Lying awake in a hotel room the night before she’s to deliver her talk, still unsure what to say, she attempts to adopt the classical mnemonic device of assigning portions of her lecture to the rooms of a familiar building—in this case, her suburban, college-town home. It’s an ode to rhetoric, to Keynes (who appears, amusingly, as Abby’s imagined spirit guide and interlocutor), and it dramatizes how understanding markets as fiction can revitalize our own market critiques.

Or does it?

The main thrust of Abby’s lecture recalls Beckert, who also leans on Keynes, in particular Keynes’s assertion that in many cases, there is “no scientific basis on which to form any calculable probability whatever. … Nevertheless, the necessity for action and for decision compels us as practical men to do our best to overlook this awkward fact.” “There is, in other words, a rhetorical side to economics,” Abby rehearses, extending the thought. “Rhetorical not in the sense of a question that you’re not supposed to answer, but in the sense of belonging to the art of rhetoric, an art that economists, like most people, tend to look down upon—‘That’s all just rhetoric!’—as if rhetoric is some horrible thing.” The most enjoyable riffing on this observation is front-loaded in the opening, as Abby and Keynes set about pedantically establishing the premise. Setting off through the mnemonic rooms of Abby’s home, which in real life she shares with her do-gooder husband and adolescent daughter, she flubs a section of her digressive lecture in each. They begin on the porch, where Keynes kindly suggests she ought to begin her talk by, you know, introducing him. A fine—and funny—opening move.

Having started in on this nervy, apologetic register, however, The Guest Lecture never quite abandons it. The effect can be winningly comic: “Of course, when an economist tells you not to worry, you might worry all the more,” Abby says. “An economist’s ‘don’t worry’ usually means something bloodlessly calculated, like ‘worrying will increase the inclination to hoard currency and decrease spending on consumer goods.’” It’s a skillful bit of rhetoric unto itself; you’d expect a self-deprecating ethos from an economist appealing to a public that has turned against the dismal science. The impulse to apologize extends so deep, however, that Abby’s qualifications increasingly seem to serve a second purpose. Is the author likewise coaxing an imagined readership to stick around, lest they slam the book shut at the first mention of monetary policy—or worse, at the first suspicion that Abby isn’t concerned with social welfare? “When [Keynes] proposed that people not worry,” she continues, “it wasn’t to paper over the inequities of a system by which the rich come to control an ever-increasing percentage of the aggregate wealth while the poor are systematically disenfranchised. He was saying that he really didn’t think worrying was the right thing to do.” Again, this is amusing; Abby does nothing but worry. But it is also relentless. Later, the anxious qualification extends to her hand-wringing over personal consumer choices:

The Guest Lecture leaves the reader wondering how much of this anxious apologizing and self-critique is humorous characterization, a necessary extension of Abby’s rhetorical strategy, and how much is a hedge against a deeply distressed literary market—an echo of the author’s plea for the reader not to come to dislike her and her kitchen too much. Nor, for that matter, the author who invented her.

The familiar economic concept of “as if” behavior, in literary circles, is more commonly known as Coleridge’s “suspension of disbelief,” the basic price of admission into a fictional world. Yet as literature transforms itself under increasing market pressures to make a buck—and as literary fiction simultaneously buckles under pressure to be ever more “truthful” and authentic, to sell the author as much as the book—this concept has slowly been replaced by the idea of the reader-author “contract,” wherein participants in a reading transaction agree upon rules of exchange. Walk into any workshop and you will hear how, like financial contracts, the agreement between reader and writer can be undersigned and broken—how, like markets, underregulated fictions can collapse. As freewheeling finance acts more and more unapologetically like novels, it may be that novels themselves are being written more and more like traditional financial instruments—carefully designed to be safe readerly investments.

The Guest Lecture, as imaginative as it is sly, pulls up just short of a further revision of these contractual terms: the suspension of perceived political disagreement vis-à-vis the author’s imagined readership. Of course, at the other end of the spectrum, a novel written simply to goad or provoke falls into a similar trap; shock and apology can serve as two sides to the same coin, tossed up to appeal to market attention. Still, the fact that provocation can be its own kind of concession doesn’t make the apologetic tic any more aesthetically salvageable, especially in a moment when we’ve begun to apologize for novels being novels, for fiction being fiction, for writing the imagination at all. Surely there are more robust literary modes of resistance against totalizing market forces? Against the pervasive insistence that reality-doubling novels should be put to rest?

●

The British novelist Claire-Louise Bennett, whose working-class protagonists imagine their way not into economic utopias but fabulous manors, feasts and other decadent tableaus, is not much interested in risk management or readerly contracts. Seizing style and excess with zeal, her most recent novel, Checkout 19, arrives as a welcome reminder of the ways in which the imagination enables aesthetic, as well as political, ambitions. After a decade of literary discussion dominated by considerations of authenticity, morality and the “real,” it feels especially refreshing for inviting a long-neglected guest back to the table: beauty.

Since the publication of Pond in 2015, Bennett has been producing some of the most stylistically interesting, baroque and market-tone-deaf fiction in the Anglosphere. Praised for jettisoning narrative expectations, dinged for a bourgeois attention to domestic interiors and a lack of plot, generally heralded as a writer of lovely, if unclassifiable, autobiography-hungry monologues, Bennett’s work is also animated by class rage. The latter is most apparent in her latest novel, released in the U.S. last March. As with Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan series, Checkout 19 presents literature as both a handmaiden to class hierarchy as well as an escape route from working-class material conditions. It has been hailed above all (and despite Bennett’s so-frequent-as-to-be-distracting name-dropping of working-class writers like Ann Quin and Annie Ernaux) as an autofictional Künstlerroman.

And it is: Checkout 19 is the story, loosely speaking, of how our unnamed narrator-protagonist became a writer. The first part of the novel proceeds as a series of surreal, fantastical stories the protagonist once wrote to entertain herself while working overtime at a grocery (she’s stationed at checkout 19) in order to put herself through university, where she studied literature alongside far more privileged and prepared students. These stories she composes—and which we have the pleasure of reading, years later, in summary form, as our narrator struggles to recall her own oblique plots—are totally decadent, stylistically flamboyant, licentiously acquisitive in their endless lists of bourgeois comforts. Her imagination is stocked with preserved lemons, opera houses and encyclopedic collections of lace. These are magical stories. A girl spinning thread in a cellar spontaneously combusts. (On finishing the tale, the author herself is shocked: “And then the pen was done, spent, happy, and lay there now, smoldering on top of the closed exercise book. Spent, yes, but I knew now what it was capable of.”) A wealthy nobleman, a cross between a Borges and a Huysmans, curates a regal library in his palatial apartment, where reams of blank books contain a single sentence; when the library burns to the ground, this solitary phrase escapes as an anthropomorphic shadow. What fascinates the narrator above all is the sanctity of beauty, especially that found in books; what enrages her is all that conspires to keep her from accessing it, especially her economic conditions, compounded by others’ class condescension. One of the more provocative experiments of the book is whether her imagined realities (in particular, her decadent conjurings) are as real as reality itself:

In both The Guest Lecture and Checkout 19, fantastical or absurdist plot elements are located explicitly in the narrator’s imagination; though it may seem unreal events occur, both are realism on a long psychological leash. Bennett more successfully explores the potential of this old trick of first recognizing the narrator has an imagination, then using it as the novel’s primary setting. (While Riker may have created the more impressive imaginary structure, the effect is undercut by the apologetic tone.) Tunneling into myriad worlds, Checkout 19 intentionally creates and destroys its own realms over and over, so that we begin to lose track of which one is “real.” This blurring distinguishes itself from market abuses of similar techniques through the self-consciousness of its own ambivalent power. The novel dramatizes both the dangers (the demotion of material experience) and potentials (generating test worlds) of “doubling reality” by toggling back and forth between the tangible and the projected.

It does so by inviting the imagination, fancy prose style and the fantastical back into fiction, freeing up a literary attitude capable of countering the “imagined futures” of financialized capitalism without denying the ways in which fiction is complicit in its logic. “We confused life with literature,” the narrator recalls of her student days,

The deep desire to reduce uncertainty, to predict the future, is the major reason, Beckert and Keynes would say, that markets exist. Novels rest easier in the ambiguity, and Checkout 19 makes us feel the poignant truth: uncertainty is unavoidable.

The pursuit of beauty, to which Bennett’s protagonist is so devoted, is subject to well-worn political critique. The philosopher Elaine Scarry provides a useful recap of the complaint in her famous 1998 essay On Beauty and Being Just. Those suspicious of beauty, she writes, often claim that “by preoccupying our attention, [it] distracts attention from wrong social arrangements,” leaving us “eventually indifferent” to injustice in the real world. As Checkout 19 progresses, we do begin to forget that these fantastical characters are make-believe, or that they don’t constitute the main storyline. The protagonist’s own reality seeps in around the edges: she’s broke; her alcoholic friend rapes her; she’s precariously housed. In a blast of rage at the end, more powerful for having been repressed for the better part of the novel, she finally finds a room of her own (she is a “visitor” in a rich woman’s house), where she reads of students from northern England who have “flattened” their accents in school for fear of ridicule: “It made our blood boil to read that. It made our blood boil. Imagine someone day in day out purposely making you feel ashamed of the sound of your own voice. Imagine what that would do to your confidence.” These are the material and class conditions in which our fantastical stories were made, and the drama of the novel hinges on the contrast.

That Bennett’s protagonist frequently writes so unapologetically for art for art’s sake is probably what led many outlets to overlook the novel’s concern for unjust social arrangements, instead celebrating Checkout 19 as a frothy, autofictional Künstlerroman. Again, it is—a fact crucial, however, to the way its frothy excesses generate an organizing mood of protest. One effect of the flamboyance is to upend any ambient elitism readers might bring to the book, for example the idea that working-class thinkers and stories are incompatible with aesthetic sensitivity or avant-garde ambition—that a novel isn’t a “working-class” story unless it’s full of grit and despair.

●

This reclamation of the aesthetic imagination for a working-class story echoes the psychological, surreal and subtly magical novels of prize-winning French writer Marie NDiaye, whose genre-defying work frequently marries formal ambition with class critique. The Cheffe: A Cook’s Novel, the English translation of which appeared in 2019, revolves (like Tár) around an eponymous, working-class female genius in a field dominated by men. (Also like Tár, it is not a true story.)

The Cheffe is a self-made culinary legend. Her prowess serves as a sly stand-in, however, for NDiaye’s arguments about the consumption and production of art across socioeconomic divides more generally. Told as a posthumous hagiography from the perspective of an obsessive and queasy-making former assistant (the narrator’s possessive adoration of the Cheffe borders on the lustful), conflicting views on her character and cooking proliferate. We begin to wonder: Who was the Cheffe, really? And to whom do her aesthetic sensibilities and achievements belong?

The daughter of laborers, brought up in poverty, the Cheffe faces a steady assault of class condescension from customers as she rises through the culinary ranks. But she is also capable of dishing it out herself. Wealthy clients are described like readers who, fed on fluff, are never satisfied, tiring “quickly even of dishes they loved, and their perpetual craving for new tastes grew stronger as they grew older.” By the same token, NDiaye hypnotically lampoons any patronizing praise:

The Cheffe turns out to be a true artist, the only one in the book, committed to punishing standards of artistic integrity. She shows outright disgust for kitschy, crowd-pleasing thrills: “Her cooking could be hard when you first encountered it, could be uncongenial, but once you’d learned to love it you felt only repugnance for any mannered, pandering cuisine, anything soft and creamy, you felt like that food didn’t think much of you, as if you were someone not much could be expected of … you don’t feel respected as a customer and an eater, you feel ashamed for the cook.” This conviction could generate its own flavor of elitism, though one suspects the Cheffe would simply call it good taste, a sensibility she considers readily available to all. She struggles to teach her extravagant clients to appreciate her subtlety while also keeping her haute cuisine affordable enough that any customer, of any background, “could approach without knowing anything about it, expecting nothing more than a full stomach.” She eschews “high-flown words” and “fancy talk.” She is an artist caught between aims of sophistication and republicanism that her immediate influences, at least, have declared to be in conflict.

NDiaye complicates Bennett’s celebration of aestheticism with broader questions of access. There are trade-offs, the novel (or at least its narrator) suggests. Though the Cheffe strives to create effortless, democratic dishes, the shifty narrator, also from a working-class background, remembers that his own mother considered her dishes food for “fairies or ogres,” and indeed “never even considered” that it was possible to walk into the restaurant “without having to prove she was a secret aristocrat, a fallen princess.” From this perspective, the Cheffe’s cuisine is “all fairytales, [my mother] didn’t believe in such things.” Warped as she is through the lens of the narrator, the Cheffe is also the stuff of fairy tales, the ambivalence of which Checkout 19 reminds us: embellishment can warp as well as reveal. There is no fairy-tale resolution of these tensions, and in NDiaye’s hands, the reader is meant to feel uncomfortable, even morally unmoored. Thrown into a small French town’s classist structure, the Cheffe’s enormous artistic talents seem to have a way of leaving everyone involved slightly ashamed and confused—except for the author, NDiaye herself.

Though the protagonists of The Cheffe and Checkout 19 take different approaches to beauty and the class codes that can encase it, they respond to similar socioeconomic and aesthetic pressures. To be either an “avant-garde” or “working-class” writer, Bennett’s narrator says of her own literary hero, the British novelist Ann Quin, “in addition to being a woman would have been sufficiently indecorous.” Yet to be both was “downright impudent, and incurred suspicion and snobbish disdain from some critics at the time.” Relentlessly acquisitive in her sensibilities, Bennett’s narrator claims all three traits—woman, avant-gardist, working-class—plus her lace, her Viennese opera houses, her rage. Because a good novelist, like a good cook, refuses to apologize for daring to make art.

●

In the end, literature’s reaction to financialized capitalism may not have been to abandon the imagination, but to embrace moral apology—including for the novel itself. It’s interesting, then, that it’s NDiaye’s The Cheffe, our French selection, that most fully explores these feelings of shame that can arise at the nexus of art, money and class. Though the novel refuses to apologize for itself, its characters are deeply unsure about where to source their dignity. The Cheffe’s bourgeois clients seek in her cuisine a reason to “stop hating what they were”; her parents, impoverished laborers, refuse her “excessively refined” gifts; the Cheffe herself is a paragon of American-style bootstrapping, though helpless to restrain her profligate daughter. (Then again, perhaps one expects no less of such a daughter, when her mother’s cooking is conceived “precisely to erase any memory of labor, of duress, of punishing hours.”) Is the Anglophone race toward reality-hungry fiction, its demotion of invented fairy tales and ogres, related to similarly complicated feelings of economic shame?

Judging from the literary criticism of the early 2020s, it would seem something ashamed and anxious is indeed at work. American critics Katy Waldman, Lauren Oyler, Becca Rothfeld and Christian Lorentzen have memorably declared contemporary realist, autobiography-hungry fiction to be handicapped by defensive “self-awareness,” “moral obviousness,” “sanctimony” and “careerism” in turn. It’s hard to disentangle these critiques from the writerly question of how to write fiction in a moment hyperaware of the gross and ever-expanding socio-economic injustices that financial markets, centered in New York and London, produce, and whose profiteering tentacles extend deep into Anglophone publishing. There is an enormous pressure to be part of the solution rather than part of the problem—and by extension, to value novels, like everything else, not for their truth or beauty but for their moral and economic use value.

It’s no mystery why Anglophone novelists take these pressures to heart: the wrong social arrangements are very wrong indeed. The United States and the United Kingdom represent the first and second most unequal of G7 nations. France, despite—and arguably because of—recent protests, is more equal, second only to Canada. In the wake of the financial crisis, America has not seen such a gross concentration of wealth in the hands of the top one percent since the 1920s. The slightly more equal U.K. still ranks among the most inequitable countries in all of Europe, with the top decile of British earners falling among the continent’s richest, while the bottom 20 percent of earners are 20 percent poorer than their French counterparts. Nor is it any mystery why, in the face of such economic injustice (and I include environmental injustice in this category), the pursuit of beauty over justice in fiction might begin to seem suspect. Beauty becomes ugly for appearing to ignore and distract from “wrong social arrangements,” as Elaine Scarry suggests, and even to broadcast indifference. As the urgency to rectify these arrangements grows, so does the pressure to apologize for the novel as a “mere” aesthetic object and experience. Short of abandoning the genre altogether, as Shields recommended in 2010, today a novel ought to help save the world. Or at the very least, to prove its use value beyond, and even instead of, the achievement of beauty or formal innovation. Above all, by being “real.”

This is all understandable. But it is also a shame. Taken to the extreme, it robs us of the vocabulary to discuss and celebrate beauty, one of the last escapes from market logic in the public sphere. This reflexive critique of beauty also seems to rest on a latent logical fallacy, namely that beauty and justice are mutually exclusive. There are myriad ways in which this assumption can be disproved, as Scarry set out to do in On Beauty and Being Just; she even goes so far as to argue the opposite, claiming that beauty in fact produces justice. It is enough for me, however, to restate what I hope Bennett and NDiaye have already made obvious: that concern for beauty and concern for justice can coexist in the same work of art.

To an Anglosphere by now accustomed to literary austerity, Bennett’s excesses feel particularly fresh. What I especially like about Checkout 19’s vocabulary for beauty is the way it so naturally allies itself with attitudes of abundance and renewability (as opposed to scarcity, austerity or apologetic retreat). That inexhaustibility and abundance are inscribed in beauty is something that strikes Scarry as well; though justice recedes from the world when we neglect to produce or create it, she points out, beauty endures in nature, ready-made, whether or not we pause to notice or care for it. Beautiful things thus have that hallmark of what Scarry calls a generous availability and what I would call a lack of self-consciousness. The impulse behind a beautiful thing—certainly behind the voice of all my favorite novels—seems it would go on existing even without an audience, in the same way a bird sings, or the sky clears, with indifference to praise or detraction; they can no more apologize for being beautiful than they can demand to be recognized as just. In a hyper-financialized moment obsessed with quantifying influence and impact, they unanxiously exist.

Millennia-long debates over the definitions of the beautiful and the hateful, good and evil, remain unresolved, so there’s little point in my trying to put a bow on things here. Instead I have a story I didn’t make up: a high-school dropout, intermittently homeless, a street fighter and drifter, as an adult teaches himself to read music and write poetry. A short composition he arranged for me on piano still hangs in my parents’ home. I used to play it as a girl. It is mediocre at best. My father once asked him why he did it. Why did he spend so many hours on poetry and music and literature when it was clear he had no talent? My grandfather replied that he was perfectly aware he was no Neruda, no Beethoven; he was no idiot. But he wanted to catch a glimpse—just a glimpse—of what it might have been like to be them. What arrogance! If you’re looking for an apology, you won’t find one here.

Art credit: (1) Danilo Correale, A spectacular miscalculation of global asymmetry #6, acrylic and oil on canvas, 60 × 50 in., 2017. Private collection, photo by D. Lasagni, (2) A spectacular miscalculation of global asymmetry #9, acrylic and oil on canvas, 36 × 30 in., 2017. Private collection, photo by D. Lasagni. All images courtesy of the artist.

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.