There’s a cabin in the hills up above Malibu belonging to a Hollywood friend of mine, where I go when I get in the mood to get away from it all. My stated intentions are watching cartoons and sleeping late, though these ambitions are predictably frustrated by the large plate-glass window in the bedroom, which along with its remote but fashionable location is definitely the cabin’s main attraction, offering what was quaintly referred to a generation ago as a million-dollar view—a figure that now has an extra zero or two appended to it, depending on the frequency of fires and mudslides in the area. The window stares directly at the Pacific Ocean, so that if you drew a dotted line directly from the spot where the early morning sun rises over the mountain to the ocean, and then back from the ocean to the window, with only a single large shade between, it hits a sleeper’s eyelids with a luminous flux of painfully literal, godlike intensity. Imagine one of those stop-action diagrams that flash on screen right before Road Runner is blown away by a bazooka.

The rest of the interior space of the cabin—maybe seven hundred square feet, with a kitchen-living room with a four-burner stove—is efficiently engineered, in a way that feels both compact and expansive, though the sheer size of the window means it’s impossible to sleep past sunrise, no matter how tight you draw the curtains. The sunlight reflected off the ocean is so bright that it feels like it is illuminating your eyeballs from within. It’s like God is taking his semiannual X-ray of my soul.

Getting away from it all is pretty much a necessity in my life these days, and I am grateful for the view, even with the early-morning wake-ups, which lack the cortisol-driven urgency of being woken up an hour or two earlier by my youngest son Elijah, who can’t sleep for more than three or four hours in a row, most likely as a result of a stroke suffered at birth. My wife is riven by Elijah’s condition, which is neither terminal nor yet entirely explicable, and has turned her into an unexpected combination of a neuroscientist and Dr. House. In supporting roles are myself, two older children and the menagerie of companionable pets—including two Siberian cats, who hate our new sheepdog puppy, which we purchased as a nod to conventional ideas of childhood joy.

So far, Elijah’s condition affects some large part of his fine-motor abilities, which include the ability to speak more than two or three intelligible words in a row. Speech is among the more complex fine-motor activities on which our humanity is founded, requiring the neural coordination of more than thirty separate muscles in the mouth and tongue. Elijah’s receptive language is at the level of a normal six-year-old, or even above that, according to various forms of more or less sophisticated testing like telling him to “please bring the paper towels to Mama in the kitchen.” (Promise a cookie, and your instruction will be completed more or less immediately.) In addition, Elijah has suffered from focal seizures on the right side of his brain since he was three, especially during sleep, when the brain is more porous and would normally integrate the experiences he has during the day. To control his seizures, Elijah receives varying dosages of medication, which are most likely responsible for his frequent bouts of morning nausea.

Other than that, Elijah is a clever, funny boy who loves his cats and dogs and may or may not gain the ability to speak, or sleep normally, or care for himself. Time will tell whether Elijah will improve or not, and to what degree, and in what ways. Every year he grows older, and stronger, and more physically difficult to manage, even as more of his underlying curiosity and intelligence shines through. Especially late at night, I strain to make sense of words and phrases that clearly have meaning to him but in which syllables are scrambled together in no predictable order. Sometimes I fear that they add up to nothing, or to something less than what I hope. In some branching number of possible universes Elijah will live with me forever, fiercely alive, though mostly mute, as we search for ways to communicate through an unstable aperture that sometimes seems like an open window and then narrows to the width of a straw.

The more selfish parts of my own nature find their own set of coordinates: 34.0259° n, 118.7798° w. I flee there every six months or so in order to write with zero distractions courtesy of my personal Gatsby, who is insanely rich if not quite so lonely as his fictional namesake, and generous in the way of people who get bored quickly with material possessions but not with people. He says he won the cabin in a poker game—which is more or less a true story. The shelter it offers, in which I cut myself off from the sustaining web of people I love and who love me back, helps restore my interdependent self to its original state of splendid isolation, in which I can endeavor at least to make sense of it all.

Hello, Malibu! Alone on a mountaintop, an atomized figment of my own imagination with nothing between the membrane of me-ness and the mirrored vastness of the Pacific Ocean, I can inhabit my own skin for hours if not days at a time. I can make notes on personal and familial suffering, read Latin and Greek, watch cartoons and otherwise do my best to figure things out. My ruler is the classical measure of man, who is himself or herself a reflection of something that is knowable only in relation to others, each of us reflecting back some aspect of the divine. Or else, the miracle of our shared humanity is only a myth, and Elijah is simply a set of mangled circuits.

In the summertime, the heat inside the cabin gets so bad by midday that it’s impossible to think straight; even with both doors open, the fan on and the windows cranked as wide as they can go to achieve maximum cross-ventilation, it takes an ice cube maybe four minutes to melt in a glass of water. The benefits of this particular set of coordinates easily outweigh the costs, though. The view is gorgeous, with no neighbors visible for miles, except for a famous music producer whose white Italian villa and backyard swimming pool are located maybe forty degrees off center from the direct view-line from the window to the ocean. I’ve seen things when I’ve turned my head that way, believe me—I can’t help it, although, to be honest, it’s never been anything wilder than pretty girls lounging by the pool with little or no clothes on, which is a sight that I am grateful for. For the most part, I find Southern California to be a grim, puritanical place, whose much-advertised hedonism is only a surface distraction from an underlying religious tone that is centered on death and involves its own distinctive modes of perversion—ranging from submission and self-denial to black magic and other ritual desecrations of the human imago, like sexual torture. It’s an anything-to-feel-something kind of place.

What I am after up here is nothing quite so extreme. I long ago adopted the post-Enlightenment model of a pleasure-seeking existence rooted in the kicks I get from music, prose aesthetics and recreational drugs, with some atavistic God-seeking mixed in. I also enjoy sweets and fruit. Depending on which way the wind is blowing, I can use my energies to make stuff up, and to wallow in my own being like a libertine hippopotamus, with only a pair of eyes and giant, flaring nostrils visible above the muck.

Still, being alone is hard work, and if you want to make it through the hours and days at least semi-intact, you need to get straight with yourself. This is a useful nugget of philosophy I took with me from the period of my life in which I worked assiduously not to use drugs. Getting straight is a chore, but it breeds its own wisdom. You need to keep looking in the mirror, even when there are plenty of excuses for looking elsewhere. Telling lies will never make you a better person or the world a better place. It is wrong to assent to propositions that you believe to be false, even if that makes you unpopular with people who aren’t really your friends (or else they wouldn’t be inviting you to do drugs). Conspiracy theories are also a kind of drug. Once you assent to the counter-reality that they posit, you forfeit your appeal to the evidence-based methods that tell you whose face is looking back at you. A touch of white hair around the temples, along with a tolerant, knowing gaze and a general tone of health and decorum, especially combined with regular physical exercise, is a better way to orient yourself.

As a writer, moreover, I pride myself on seeing things not just clearly, but early. And what I saw from my loaner cabin in 2019 was the same thing I saw upon my return to the mountain a year later, when the connections between my own drive toward silence and isolation and the combustible nature of my surroundings had become too obvious to ignore.

The wildfires came first. Then came the pandemic, followed by a protest movement whose initial focus on police violence quickly broadened out into a roiling nationwide revival movement emphasizing the omnipresence of racism and other sins whose origins lay deep in America’s past. The fires, the plague, the turmoil on the streets and the sins of America’s past were all real. But the urgency of these problems, whether taken alone or together, didn’t explain why the whole country had been put on tilt. The real message was in the velocity with which generally agreed-upon perceptions and social habits appeared to flip 180 degrees from one week to the next, pressed forward each time by the urgency of the demand to refigure reality.

This sense of a foundational shift had not arisen organically, in response to events. Rather, it was part of the functioning of a new machine, made up of data-driven tools and platforms whose feedback loops had been fashioned according to the addictive logic of corporate advertising. The machinery made it easy for small groups of self-aware agents, whether driven by ideology, or money, or personal appetites for chaos, to rapidly empty out shared, socially defined abstractions like “America” of their familiar meanings and invent in their place new narratives, oriented toward a new future in which “justice” would replace “happiness” as America’s big rock-candy mountain. The failure of these promises would in turn provide more fuel for the machine.

A new country may yet be formed from such operations, but it is unlikely to be called America. That’s because, for the creators of the new American future, “America”—which is a particular kind of human experiment grounded, in its four or five distinct historical incarnations, in the democratic argot celebrated by Walt Whitman, Louis Armstrong, Chuck Berry and other great American poets—is precisely what needs to be undone. The birth of the new un-America is therefore a tragedy, at least according to the Greek idea that fate is inescapable. It is fueled by the same radical individualism, the same determination to inhabit the never-ending future-present, that made the country, for a time, such an inescapable success.

●

To get to my friend’s cabin, I drive up a traffic-choked stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway leading out of Los Angeles, then duck into the third canyon exit after Topanga. Then, guided by Google Maps, I drive up through two canyons and along a series of twisting roads, past homes teetering precariously on the edges of cliffs like stray sprinkles on the side of a burnt-over cupcake. The driveway to the cabin is at a steep incline, such that the house is invisible from the road. I ease my old Mustang nose-down, at a 45-degree angle, until it bottoms out near the garage. I am home free, nearly. Eleven more staggering steps and I can sit down on a bench underneath a tree that provides blessed shade and stare out at the ocean and the music mogul’s swimming pool.

The news on my phone and on the large-screen television inside is all about wildfires, which seems like as good a place as any to start. The state of California is on fire, starting perhaps thirty miles from the cabin and extending as far north as Mendocino. Entire forests are spontaneously combusting, sending rivers of flame down hillsides and into valleys, where they find still more fuel, overwhelming the scarce resources and ingenuity of the firefighters who are heroically withstanding temperatures of 120, 140, 150 degrees Fahrenheit. When the fires get too hot, the firefighters fall back to the next firebreak and hope that the wind shifts or that the fuel supply gets low enough for a line of fire trucks assisted by helicopters and maybe a giant propeller plane, a marvel, to swoop in and douse the edge of the blaze, giving the firefighters some time to catch a breather. Plumes of gray smoke from the fires are visible to the north and west of where I sit.

Fighting wildfires involves young people risking their lives by jumping into flames when every human instinct is telling them to run. This is a kind of heroism that no longer interests the narrative “us,” just as we are, supposedly, no longer interested in fire as a means of appeasing the gods or aiding in purification rituals. What interests us nowadays is the question of who is responsible for the fires—a question as old as Salem but now updated to align with the latest revisions to the American occult. Wildfires are no longer acts of God, or elemental confrontations between man and nature: they testify to the urgency of climate-change models, or symbolize the evil of big power companies, or homeless migrants, or off-the-grid devotees of QAnon.

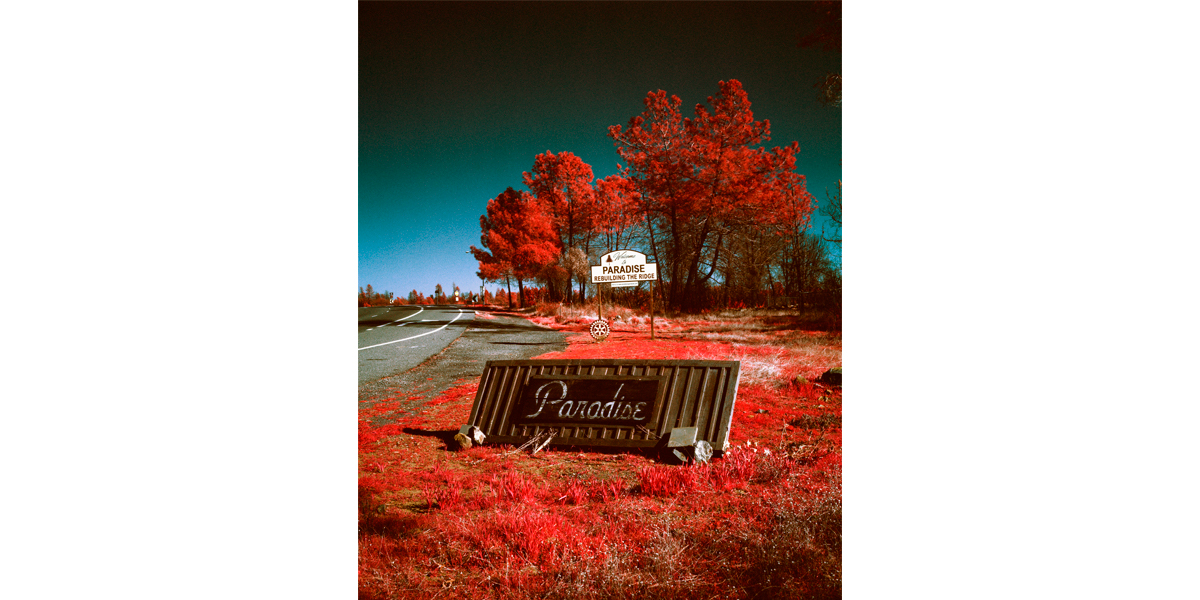

A case in point: On the morning of November 8, 2018, the previous fall, a seventy-year-old retired jeweler named Don Peck awoke to loud explosive sounds outside his home in Paradise, California. “It was boom, boom, boom,” he recalled later to a reporter. What he heard was the sound of propane tanks exploding as the town caught fire. “It was late in the morning, but it was dark as midnight,” he recalled. Jumping in his Chevy pickup, he made it to the highway to Chico, which was gridlocked. “There were a lot of these little buses that are used to take older folks around. The lights were on in some of them, and they were packed. And I could see that everyone was petrified. No one knew if they were going to get out alive.”

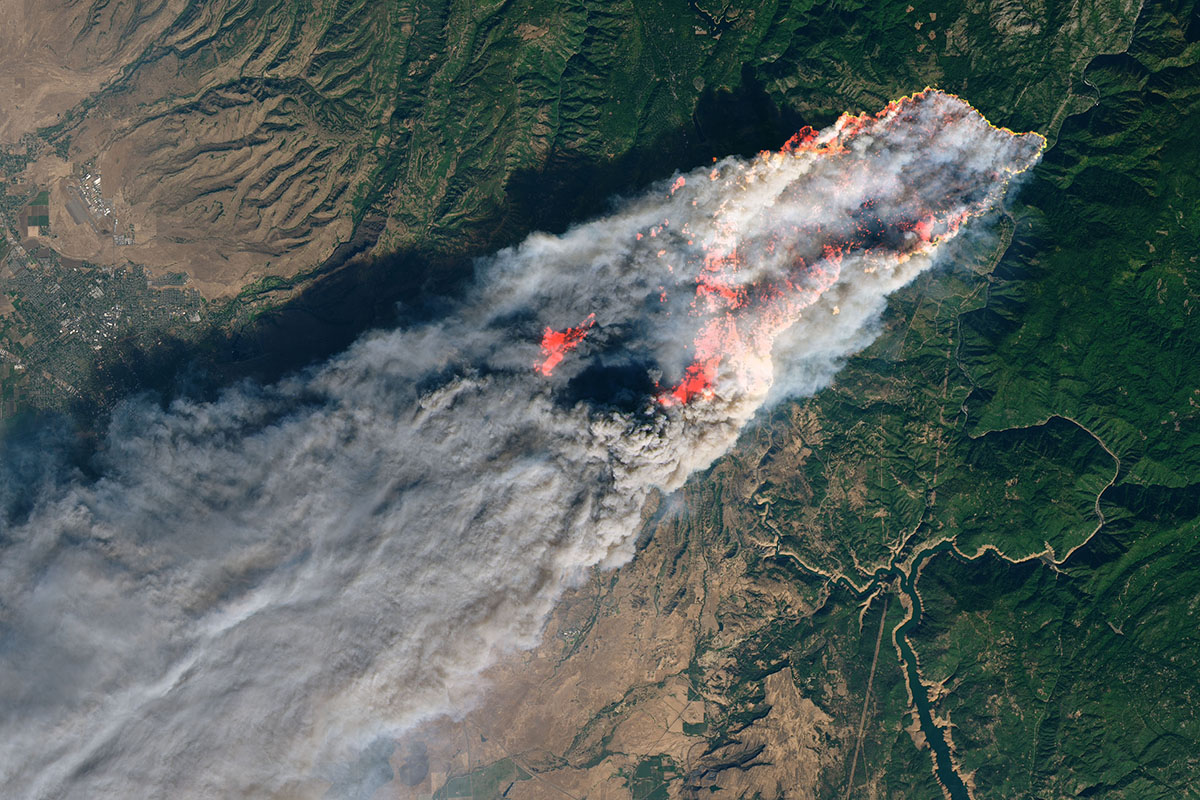

The Camp Fire, the name of the wildfire that ignited the town of Paradise, taking the lives of 85 people, was the most destructive blaze in California state history, more than three times as deadly as the Tubbs Fire, which had consumed five thousand buildings with 22 dead the previous year. “The scale was astounding,” said Scott Stephens, a professor of fire science at UC Berkeley and an expert on wildfires. “You essentially lost a whole town.”

In its “very meticulous and thorough” investigation of the Camp Fire, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection found a clear culprit: Pacific Gas & Electric, one of the state’s largest and most hated utility providers, which filed for bankruptcy in January 2019, citing an estimated thirty billion dollars in fire-related liabilities. The Cal Fire report provided an entirely coherent explanation for how the fire started and spread; the investigators even furnished photographs of a rusty metal hook whose failure had allowed a PG&E power line to ignite the blaze. Yet if the charge was in fact true, the report was still misleading in a way that would become part of a pattern of simplistic scapegoating and blame-mongering in wider media narratives, deflecting attention and energy away from the kinds of systemic solutions needed to actually help prevent future fires. The implication in the coverage of the Camp Fire was that the broken metal hook and other particulars painstakingly documented in the report were unique or unusual occurrences. In fact, failing PG&E power lines had caused more than 1,500 wildfires in California over the past six years alone—most recently the Dixie Fire, which was sparked this July only a few miles from where the Camp Fire began.

With each destructive fire, the media looks for new culprits, their attention wavering between corporate villains and human ones. The Holy Fire, which burned around 23,000 acres near Lake Elsinore, was ostensibly the fault of one Forrest Gordon Clark, an Orange County man who had expressed support for what the press called “alt-right conspiracy theories” on his personal Facebook page. The posts, uncovered by J. J. MacNab, a Forbes columnist who writes on right-wing extremism, included a couple about Agenda 21—a fringe theory that posits that nefarious politicians and environmentalists are behind the fires. Others were in support of the QAnon conspiracy theory, an elaborate multiplayer participatory role-playing game whose apparent premise was that President Donald J. Trump was secretly orchestrating a day of reckoning for elite pedophiles, under cover of the Special Counsel investigation led by former FBI Director Robert Mueller. It is not clear how any of these posts incriminated Clark; nevertheless, he remains in jail to this day awaiting trial, unable to make his million-dollar bail, even as the lead investigator in the case has acknowledged under questioning from Clark’s attorney that there were at least two other possible causes of the fire, and that he “made a mistake” in identifying where it started in his initial report. Clark himself claims to have no clear memories of the day the fire started, and has blamed both his neighbors—one of whom was a volunteer firefighter—and “Mexicans” for igniting the blaze.

Focusing on the particulars of any one fire had the advantage of allowing investigators to focus on discrete causes that, presumably, could be addressed with better planning, regulation or (in Clark’s case) comprehensive surveillance of U.S. citizens and residents based on their personal belief systems and mental-health statuses. Yet the costs of these solutions were rarely accounted for. In order to keep power lines from sparking in dry, windy conditions, for example, PG&E began routinely cutting power to millions of Californians—who over decades had decided it was safe to locate homes in formerly wild or thinly populated areas, which were duly connected to power grids and to the state’s enviable system of roads. After the Kincade Fire destroyed 78,000 acres of California wine country, forcing 180,000 people to evacuate their homes, the power cuts caused millions more Californians, many of them elderly or otherwise vulnerable, to go without electricity in the broiling heat.

As the search for a culprit for seasonal wildfires continued, the press predictably turned to Donald Trump—attacking the president’s refusal to publicly acknowledge what the AP referred to as “the scientific consensus that climate change is playing a central role in historic West Coast infernos.” If Trump or his batty supporters weren’t starting the fires themselves, a deluge of reports suggested, they were responsible for bringing on the catastrophe by failing to pay proper obeisance to the science gods.

The suggestion that Trump was personally to blame for wildfires struck an understandable chord with California state officials, who otherwise might themselves have been forced to answer for the state’s inability to apply basic fire science to managing state-run forests and other lands, as well as a decades-long libertarian approach to zoning laws that had settled millions of people in fire zones. “Something’s happened to the plumbing of the world, and we come from a perspective, humbly, where we submit the science is in … that climate change is real, and that is exacerbating this,” Governor Gavin Newsom humbly ventured, as if acknowledging the reality of climate change was the only thing standing between the wildfires and hundreds of thousands of acres of timbered dry land where Californians had decided to build homes, often with the support of the state.

The search for a culprit for the fires continued on through the fall and into the next year, whenever fires blossomed. “Our 9-1-1 dispatchers and professional staff are being overrun with requests for information and inquiries on an UNTRUE rumor that 6 Antifa members have been arrested for setting fires in DOUGLAS COUNTY, OREGON,” the Douglas County Sheriff’s Office wrote in a Facebook post in the summer of 2020, amid mass public protests over the death of George Floyd at the hands of police. Sheriffs in Jackson County, Oregon, and Mason County, Washington, posted similar warnings. The FBI’s Portland field office, which was busy monitoring protesters throwing Molotov cocktails nightly at the city’s federal courthouse, tweeted that reports about “extremists” setting wildfires were untrue. The lack of any evidence presented to demonstrate the truth or falsity of these claims had by then been normalized in a society where “truth” was no longer connected to methods of gathering evidence and calculating the relative weight of causes and effects.

My considered personal response to the proliferation of these stories and the new national sports of scapegoating and meme-making was a determined—if not always successful—resistance to reading them at all. As a reporter, an activity I fell into in my youth due to my enthusiasm for Whitmanesque encounters combined with my inability to keep regular hours, I was trained to evaluate whether statements were true or false; and I was regularly told to reject the false ones, even if they were “well-meaning.” The term of art I learned for falsehoods consciously proffered by a government or some other group or entity in order to promote “the common good” was “propaganda.” It was a point of honor as a journalist not to be taken in by propaganda. Distributing propaganda was an abuse of the trust of one’s readers as well as one’s peers, who would avoid drinking with you in bars.

The abandonment of the hallmarks of the objective journalistic voice for what were in many ways a diametrically opposed set of qualities was impossible for any honest reader to miss. Now the news on every side was structured by narratives of collective guilt, where the heroes and villains were known in advance and the willingness to endorse obvious falsehoods was a proof of virtue. For me, this was a particularly American kind of tragedy. The values I had been raised with and taught to see as foundational had been sacrificed to a future that had not yet arrived. Yet the belief in progress that gave the new un-America its legitimating force was recognizably American, too. So maybe I was the un-American.

Seen from another perspective, though, a sense of unalterable fate was hardly foreign to the culture that had shaped me. During what might be called America’s Greek decades, which began with the presidency of John F. Kennedy and ended with the country’s unexpected triumph in the Cold War, the idea that human beings are powerless to control their fates, much less realize sweeping programs aimed at realizing the heaven of justice on earth, was common knowledge among educated people. John and his brother Robert Kennedy, who were avid readers of Edith Hamilton’s essays on the Greeks, were both assassinated. In his famous speech about going up to the mountaintop like Moses, delivered just days before his own assassination, Martin Luther King, Jr. foresaw his own death. Stanley Kubrick, in 2001: A Space Odyssey, showed us the results of trying to establish utopia through sending advanced technology into outer space. That dreams of personal and social transformation ended in bloodshed and disappointment was hardly a surprise to any of the writers who made the Sixties and its aftermath their subject, from Joan Didion to Robert Stone. Vietnam was a Greek tragedy, as was the antiwar movement it inspired.

Even in the 1970s and 1980s, the ghosts of America’s Greek past still wandered the halls of my elementary and secondary schools. Steel placards affixed to the walls made sure that we were aware of the location of fallout shelters. If nuclear war destroyed life as we know it on this planet, we were taught in our classes, it was likely to have been started by human error, or perhaps by the advanced machines we invented playing doomsday games with themselves. That the result would be the end of life on earth was hardly surprising to any of us. Reading good books, listening to music, enjoying decent food and as much sex as possible, and taking long walks through the cemeteries of Cambridge, Massachusetts, where you could commune with faded tombstones and the Puritan divine while high on whatever drugs were available, were all enjoyable or at least acceptable occupations while awaiting the inevitable end of humankind. The more human capacity increased, as the result of our drive to master new technologies, the sooner the end would come. Hopefully, one was privileged to spend however long one had in the company of people who shared one’s own aesthetic preferences and were not pointlessly cruel.

●

Here are some statements of the type that I was raised to think of as useful. Wildfires are a fact of nature that predate the existence of human beings on earth. Although drier and hotter climate conditions have doubtlessly increased the duration and intensity of recent wildfire seasons, the fires on their own can hardly be said to prove or disprove sweeping statements about the rate or causes of climate change, which in turn can hardly be held responsible for the ancient phenomenon of wildfires. From the point of view of understanding wildfires as a natural phenomenon, it makes no difference whether the initial spark is set by a homeless vagrant, a Trump voter, a power company or a mid-October lightning strike. The fires do not wax or wane depending on who is in the White House, which is a belief more appropriate to Shakespeare’s time than to ours. They are, however, a phenomenon that, like most others, has proven to be susceptible to historical and empirical investigation—as well as to increasingly advanced forms of physical and mathematical modeling, which provides evidence both of the power of machine-based computation and of its inherent limits.

Up in the mountains above the Pacific, watching cartoons all morning and eating Cocoa Krispies by the bowlful, it is possible to entertain both the idea that science is good and also that our ancestors had wisdom that we lack. The story of how modern science mastered the physics of fire turns out to have little if any impact on the way that we fight wildfires. Still, it is an edifying story, which ought not to serve as a spur to hubris. The more powerful our tools get, the more primitive our explanations become.

The first significant attempt to construct a model for the spread of wildfires, I learn from the folder of scientific papers I brought along with me to the mountaintop, was made in 1946 by W. L. Fons, an engineer then working for the U.S. Forest Service’s California Forest and Range Experiment Station. In a journal article entitled “Analysis of fire spread in light forest fuels,” appearing in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Journal of Agricultural Research, Fons focused his attention on the head of the fire, where there is ample oxygen to support combustion. Because sufficient heat is needed to bring the adjoining fuel to ignition temperature, Fons reasoned that fire spread in a fuel bed can be visualized not as a single event but as a series of successive ignitions whose rate is determined mostly by ignition time and the distance between particles.

Fons’s early ideas have generally been confirmed by work in flame-spread theory, which has established that heating the fuel ahead of the flame as it progresses is the essential process of the flame-propagation mechanism. The connection between the foundational science of wildfires and other social phenomena being reported in almost the same breath on the same information platforms and broadcasts isn’t particularly hard to fathom. The ground is either prepared for fire to spread or not. If it isn’t ripe, then the spark doesn’t matter. If it is right, then the spark doesn’t matter either.

Like many theoretical models, the Fons model had both the advantage and the disadvantage of stripping a set of complex interactions down to powerful single-factor equations, with supposedly nondeterminative information removed or filtered out. In the case of wildfires, Fons applied the energy conservation equation to a uniform volume of solid particles exposed to an ideal fire line on flat ground with no wind, eliminating other variables. Despite such limitations, however, his approach has proved surprisingly robust, and lives on in the DNA of the U.S. Forest Service’s most-used wildfire-modeling software, FARSITE, which additionally uses the Huygens principle of wave propagation to predict the shape and direction of the fire front.

Yet what Fons’s simple but powerful equation failed to account for is the way in which fires make their own weather, which feeds back into the system in real time. This has made incorporating all of the variables in a fire environment devilishly hard to conceptualize. This problem was addressed, at the theoretical level, by the next major advance in postwar wildfire modeling, which was made by a man named Richard C. Rothermel. Like Fons, Rothermel was a Forest Service engineer. Yet other experiences also informed Rothermel’s ability to understand wildfires as one part of larger destructive forces: after receiving his bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering from the University of Washington, Rothermel had served as a special-weapons development officer in the U.S. Air Force, and then in a General Electric program to develop nuclear-propelled aircraft based at the National Reactor Testing Station in Idaho.

Rothermel’s real-world experience and mastery of sophisticated engineering tools developed by the American nuclear-warfare complex allowed him to more fully imagine and predict the fast-moving devastation that wildfires can cause. His 1972 paper, “A Mathematical Model for Predicting Fire Spread in Wildland Fuels,” was a summa of ten years of empirical observation and fire research aimed at providing “a method for making quantitative evaluations of both rate of spread and fire intensity in fuels that qualify for the assumptions made on the model.” The model was designed to simulate a fire that had stabilized into a quasi-steady state, assuming an elliptical shape with the major axis in the direction most favorable to further spread. When the fire is large enough that the spread of any portion is independent of influences caused by the opposite side, it can be assumed to have stabilized into what is called a “line fire.”

Crucially, Rothermel observed that the initial growth of a forest fire occurs in the surface fuels, meaning combustible materials that are supported within six feet or less of the ground. If sufficient heat is generated, the fire can then grow vertically into the treetops, causing a crown fire to develop. The difficulty of the more sophisticated fire modeling that Rothermel attempted is that each of the two types of forest fires—ground fires and crown fires—behaves differently, and their interactions are therefore highly unpredictable, especially when combined with wind and other variables (Rothermel finally published a paper that directly addressed the way line fires and crown fires intersect in 1991). To analyze how a fire is likely to spread, one must model those interactions and identify how and when they are meaningful.

The heat required for ignition, Rothermel observed, is dependent upon three factors: the ignition temperature of the fuel, the moisture content of the fuel and the amount of fuel involved in the ignition process. An optimal arrangement of fuel will produce the best balance of air, fuel and heat transfer for both maximum fire intensity and reaction velocity—i.e. the situation that forest managers wish most to avoid.

By applying the Rothermel model, the U.S. Forest Service and state and local authorities could in theory predict where and how fast a wildfire might spread, and systematically apply management techniques to avoid or lessen their impact. “A method for forecasting the behavior of a specific fire eventually will be developed,” Rothermel predicted. “Most likely, it will be patterned on a probability basis similar to that used for forecasting weather.”

Today, we have vastly more sophisticated fire models at our disposal, such as the Coupled Atmosphere-Wildland Fire-Environment (CAWFE) model, and the FIRETEC model developed by the Los Alamos National Laboratory, as well as the two-dimensional FIRESTAR model. Many of these more advanced modeling systems use computational fluid dynamics and neural networks to simulate real-time feedback from the fire into the atmosphere. These are not widely used in the field, however, as they are way too slow to keep up with a moving wildfire. Rothermel’s hope that his model would inspire more successful applications of systems-management techniques to preventing wildfires has yet to be realized.

The reason for this failure seems obvious to me, as it should to any product of my own time and place. Namely, that the problem was not the kind of thing we’d ever be able to solve with technology. Wildfires are, after all, a normal part of California’s ecology, from the northern forests to the deserts in the south. Fires clear out decaying vegetation and restore nutrients to the soil. They encourage plants and wildflowers to bloom. Long before European settlers arrived, California’s air was filled with smoke from fires ignited by lightning strikes and by indigenous people who sought to clear land for agriculture and hunting: according to some estimates, 4.5 million acres burned annually.

Accepting such facts would mean focusing less on preventing wildfires from starting or spreading, and more on mitigating the harm they cause. “When I worked for the Forest Service,” wrote Glen Martin, a former Forest Service employee, in California magazine, “the agency was focused on maximizing timber harvests. Fire crews would spend the autumn months burning slash in immense clear-cut units that had been logged in the summer and spring. The trees taken were typically old-growth ponderosa pine and Douglas fir, conifers that had taken centuries to mature. After burning, the units were quickly replanted with Douglas fir seedlings bred for rapid growth.” Through these destructive practices, Martin explained, the Service transformed healthy forests into “gigantic fuel reservoirs” for wildfires like the Rim Fire, which began in August 2013, then burned for more than a year in the Stanislaus National Forest and in parts of Yosemite National Park, kicking off the current wave of reporting on Western fires. The fuel provided by immense plantations of young trees in the Stanislaus National Forest was augmented by vast stands of dead trees that were never cleared out. “Yosemite fared somewhat better,” Martin noted, due to fuel reduction efforts of the type advocated by the arch-science-denier Trump.

A decade of deadly fires was oxygenated by variables of greed, mismanagement, ignorance and wistful idealism that no modeling system will ever be sophisticated enough to prevent. As usual, the problem is us.

●

The equations that govern the spread of wildfires are useful metaphors for how complex human societies come apart. There are the effects of clear-cutting, of sameness, of divisive social fracking, of the destruction of economic and social bonds that are replaced by the detritus of fractured identities that subsist on virtual oxygen. All of these developments are inherent in a capitalist order whose disintegrative effects are put on steroids by digital technologies introduced into a society that has already embraced the nightmare vision of solitary atoms interacting with each other in empty space. Once the religious and socioeconomic basis for real solidarity between people is destroyed, the lone humans left behind are easily magnetized by whatever ersatz and infinitely malleable definitions of self the machines and their operators produce. These fragmentary identities act like a drug: because they can never compensate for the loss of living human bonds, or provide anchoring in any firm set of arrangements, let alone the promise of the afterlife, they create an endless supply of free-floating anxiety, which can be easily manipulated into whatever shapes their operators desire.

The perception of these phenomena and the distinctive emotional landscape they produce is shared across the political spectrum, even if the vocabularies on hand to articulate it are often unsuited to the task. “I think the part of it that is generational is that millennials—and people, you know, Gen Z, and all these folks that come after us—are looking up and we’re like, the world is gonna end in twelve years if we don’t address climate change,” explains Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. “How are we saying ‘take it easy’ when the America that we’re living in today is so dystopian, with people sleeping in their cars so that they can work a second job without health care and we’re told to settle down. … I wish I didn’t have to be doing every post, but sometimes I just feel like people aren’t being held accountable.”

Congresswoman AOC’s diagnosis (if not all of her wording) is right on. It is also the mirror of the diagnosis of the populist right, which protests that an undemocratic elite is using the corporate state as a tool of censorship and repression—a position that I personally adopt, in the spirit of the sixties Free Speech left. Such fine-grained distinctions are of purely sociological if not archaeological interest, though. Left or right, it’s all the same wiring under the hood. The dysphoria of the young, whose lives are most directly threatened by the onrushing forces of disintegration and systemic oligarchy, makes perfect sense; the flip side of that dysphoria being a paradoxical quest for certainties and absolutes, while a small number of monopolistic entities—Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, Google, Facebook and the rest—have created an American oligarchy that rivals if not surpasses the late nineteenth-century regency of the Morgans, Rockefellers, Carnegies and Goulds.

From my perch up on my mountaintop, watching Lilo and Stitch and listening to the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, it doesn’t take much in the way of prophetic gifts to see that the profoundly limitless American landscape, as first sketched out by Herman Melville, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman and then Mark Twain, and which was born again in the work of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Charlie Parker, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and dozens of other pioneers and spiritual argonauts of every race and creed, is burning. The power of a shared, future-oriented culture was the great innovation of the Americans. It was the fuel that powered the country’s rise from a colonial backwater to the most powerful nation on earth. That country is gone now, done in by the titanic wave of creative destruction that it unleashed upon the entire planet. (Among America’s great seers and visionaries, it was, unsurprisingly, a line of female artists running from Emily Dickinson to Willa Cather to Joan Didion, who registered earliest where that wave would crash, and knew enough to get out of the way.)

When the country visibly came apart in the summer of my second visit to the mountain, it had the feeling, to me at least, of a final moment of disintegration, from which a return was no longer possible. The signs of widespread social schizophrenia were everywhere, from the ruined cities to the burning forests, from Antifa to QAnon. The Great American Crack-Up was hardly the product or the property of any particular political tendency. Both sides were batshit. The COVID lockdowners and anti-vaxxers, like the Oath Keepers storming statehouses at the behest of the FBI, were impossible to categorize in terms of either right-wing mania or progressive hysteria. In the blink of an eye, defining ideological polarities could be reversed, with the right decrying late-stage capitalism and liberals tarring their political opponents as Russian agents and spies. The binaries on which the discursive system was based failed to reliably generate any stable meaning because they no longer described America as it now existed—a dead forest, waiting for a match.

●

Of the many reports from the front lines of the combustion last summer, my favorite was the Twitter feed of a former U.S. Marine turned reporter named Julio Rosas, who chronicled the birth and disintegration, within the span of a week, of Seattle’s Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, or CHAZ. The CHAZ seemed to arise overnight, heralding the arrival of new doctrines and new forms for American society, in a replay of the Puritan founding moment. At the same time, it was hard to shake the sense that it was all a sham, a kind of new media cosplay spectacle whose purpose was to generate viral imagery, which in turn failed to mean anything at all.

On June 9th, Rosas noted the birth of a new polity in downtown Seattle, the city that gave birth to Boeing and Microsoft. “Protesters have put on the barricades that those coming into the area are ‘now leaving the USA’ and entering the ‘Cap Hill autonomous zone’ or ‘Free Capitol Hill.’” On the order of the city’s mayor, the police made no consistent efforts to assert their authority. “SDOT has moved into the area to remove some of the barricades,” Rosas observed. “They have negotiated with the protesters to leave most of the barricades in place. Protesters said they want them in place to keep white supremacists out.” “Protesters have now taken over the lobby of Seattle City Hall,” Rosas noted a few hours later. “Again, don’t see any police.” Rosas illustrated his account of one evening’s activities with a photograph of a dumpster fire.

On June 12th, Rosas took a picture of a co-op in the CHAZ that was set up to meet the needs of residents of the autonomous zone. The co-op refused cash or donations in kind. Instead, it would function on a new basis. As a sign outside put it, “kindness is our currency.” Soon, Seattle’s large population of homeless people, drug addicts and the mentally ill made their way to the CHAZ, and began getting into fights with the young idealists, social-media addicts and LARPers. “People are getting into a confrontation, not sure why,” Rosas recorded. “I was asked to not record the incident by someone.”

Even from my mountaintop, the rhythms of life in the CHAZ became weirdly predictable. “Arguments are breaking out in the ‘Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone’ as some people want to take down the CHAZ street sign while others want to keep it in place,” Rosas observed. An update soon followed. “It appears the CHAZ street sign is staying for now as the man climbed off the ladder and a struggle broke out over control of the ladder. A woman asks, ‘Is anyone in charge?’”

With companies like Microsoft safely located in secure suburban campuses, Seattle’s “downtown” could be seen even by responsible adults as a stage set, rather than the heart of anything essential—so why not put on an educational play for the entire country? “A ‘Conversation Cafe’ has been set up in CHAZ,” Rosas noted. “Some of the rules: Speak your truth, celebrate differences and similarities, and center people of color.” Absolutely. Why not? Yet the great social experiment in the CHAZ would ultimately founder on the fact that it reflected no shared reality belonging to any definable group of people—it was based, instead, on the negation of all existing realities. The CHAZ was street theater with no clear plot—and therefore with an inherent tendency toward greater radicalization, on its way to consuming itself.

“There is a growing consensus to rename the area from the ‘Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone’ to the ‘Capitol Hill Occupied Protest,’” Rosas noted. “A scuffle broke out in the zone after a man came around screaming that this is a ‘Christ Zone.’ A masked guy then tried to block my phone from recording the incident.”

The search for ideological consistency, or any other kind of coherence, within the transient impulses that animated the CHAZ/CHOP from one moment to the next was bound to be disappointed, just as the rush to blame QAnon for the Holy Fire or a rusty PG&E hook for the Camp Fire had only the surface appearance of empirical explanation. Forests of dead trees, invasive ideological species, the chopping up of communities and institutions into smaller and smaller units, are all effects of atomizing processes propelled by the logic of capitalism, by the power of digital technologies and by the larger disenchantment that makes both capitalism and technology possible. Atomization, de-regimentation, widespread bans on public gathering; automated platform censorship of public speech and opinion at the behest of the White House; the labeling of tens of millions of people as “racists,” “white supremacists” and “domestic terrorists” based on their voting habits and preferences; the transformation of work, school, social life and commerce into passive experiences that involve accepting ever more convoluted and far-fetched “scientific” explanations while waiting for Amazon boxes to arrive on one’s doorstep; these were the constituent components of a highly combustible reality that was no less real for presenting itself to its participant-audience as a massive multiplayer role-playing game. A spark from anywhere would be enough to set the entire forest ablaze.

“As the American flag people tried to leave the CHAZ, some drink was … thrown on them,” Julio Rosas tweeted. I read, sitting in my underwear overlooking the music mogul’s swimming pool by the Pacific. “The crowd called them white supremacists. One CHAZer asked how a black man simply holding an American flag makes him a white supremacist.”

“Can confirm this sign in the CHAZ is real. It says this plot is for black, indigenous, and their plant allies for gardening.”

●

My friend—the one who loaned me the Malibu cabin—partied with Basquiat. They were young painters together. His friend, who was a fixture on the downtown club scene, and died of a drug overdose at the age of 27 after more or less departing planet earth through the habitual use of cocaine, wouldn’t mind being used as a token in multinational tax scams any more than he would mind being used as a racial totem by culture warriors who have zero feels for the humor and madness inherent in art. Artists are crazy, wonderful people who make something out of nothing, which is the realest form of magic. Being more sensitive types than Americans generally allow, artists are particularly vulnerable to being abused by rich people who patronize their work while protecting themselves from the risky consequences of defying convention, which usually involve dying alone. In its outlines, at least, that was Basquiat’s story.

“Hello, sport!” he exclaimed in our last pre-pandemic meeting. I met the friend through my agent, after he bought an article I wrote for the New Yorker about a nineteenth-century con artist who named himself Lord Gordon-Gordon and briefly took the Erie Railroad away from Jay Gould, the sharpest robber baron of the age. When we meet up for drinks at the Beverly Hills Hotel, he is usually wearing a bowtie with a sweater vest or some other kind of archaic getup, his hair slicked back like the twenties movie star Rudolph Valentino updated for the prosperous 1990s, which was the last time that America felt normal to either one of us. His gleaming smile seems no less sincere for the wealth of fine cosmetic dentistry it reveals.

“Welcome!” he says, as though he owns the place. After 45 minutes of shop talk, he hands me the keys to his place and vigorously clasps my hand, like I am doing him a favor. No doubt I’ll create something new and amazing, while living off peanut butter and canned beans up there on the hillside. We are both children of the assured mutual destruction of the last decades of the Cold War that rendered life pointless and meaningless through the specter of an apocalypse that somehow never arrived. Instead, it mutated into whatever Matrix-like recurrence we are living through now.

My own theory about Gatsby is that the mystery of the novel, which is the source of its lasting appeal as well as its place in the American canon, has always been plain. Gatsby is an only lightly coded story about the assimilation of Jews into Protestant America—Fitzgerald’s more sophisticated, multilayered counterpart to Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. Evidence for my thesis is everywhere in the book. Jay Gatsby was previously Jay (maybe Jacob) Gatz (or Getz), a man of mysterious origins and a longing for something larger than himself that he can only distantly glimpse in the shimmering darkness surrounding his East Egg mansion. He orders his dozens of colorful cotton shirts from a tailor in London, who is no doubt named something other than Lipschitz.

Gatsby is the great American Jewish novel about the limits of the grace that America bestows on its children, written by a Catholic from St. Paul, Minnesota who went to Princeton but nevertheless felt himself to be a lifelong outsider to WASP America. Fitzgerald could write the ultimate Jewish-American book because he was an artist, and because he lacked a certain kind of Jewish anxiety, which would manifest itself in the decades to follow as a compulsive belief in the American future—i.e. the desire to silence the inner voices telling you to stop. Part of the beauty and terror of Fitzgerald’s America was that even the wised-up outsiders became the ultimate victims of the con.

As an outsider to the Jewish story, as to every other story, Fitzgerald could admire Gatsby’s generosity, his inventiveness and his ability to dream big dreams, without feeling obliged to either share in his optimism or to debunk it. Fitzgerald would return to the tragic-optimistic theme of Gatsbyesque self-invention at the end of his life with his thinly disguised portrait of the Jewish-American movie producer Irving Thalberg, The Last Tycoon. Fitzgerald’s early understanding of the promise and lack of fulfillment inherent in the American future, which exists half in the future and half in the present, helped define the incredibly vibrant century of American culture that followed, which is now being comprehensively undone.

Gatsby’s funeral is attended by only one of the book’s major characters, Nick Carraway—Fitzgerald’s stand-in. The morning of the funeral, Nick travels to New York to see the gambler Meyer Wolfsheim, whose cufflinks are made from human molars—a perfect detail of Fitzgeraldian bar talk—to ask him to attend, but he refuses the young man’s entreaties. “I can’t do it,” the gambler says. “I can’t get mixed up in it.”

While the character of Wolfsheim was easily recognizable to readers as Arnold “the Brain” Rothstein, the well-born New York Jewish gangster who fixed the 1919 World Series, the mystery of Wolfsheim’s relationship to Gatsby is never overtly explained in the book. Yet it is clearly a paternal one. Wolfsheim is a representative of the Old World, who aspires to manipulate American fantasies, not assimilate to them. Gatsby is his progeny, who has successfully oriented himself toward a future that is always receding from view.

“Watch out for wildfires,” my friend warns me, handing me a familiar red leather fob with the keys to his cabin. “And if they come, don’t forget to get the hell off that mountain.”

●

Soon, sometime in the very near future, by which I mean now, millions of people will no longer find it interesting or pleasurable to think of themselves as Americans. Already, some of them are planning to go to Mars. Truthfully, the idea of colonizing Mars doesn’t seem any crazier than the idea of leaving the Old World on leaky wooden ships. But the race between Elon Musk and his fellow billionaire space hobbyists Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson marks the end of the American story that began with the Pilgrims and the founding of the Republic and continued on through the race westward to California and the end of Gatsby’s dock. It’s all part of a logic whose tragic end is obvious, and at the same time impossible for us, as Americans, to ever admit to.

Outside my window, the large pillars of smoke I glimpsed yesterday appear to have moved much closer. But what’s the point of worrying about that now? In addition to his efforts to colonize Mars, Elon Musk also has a “hobby company” called The Boring Company. It started as a joke, then Elon decided to make it real, and began digging a tunnel under LA, where the traffic is horrible. So Elon plans to build tunnels, on multiple levels. “You can have one hundred levels of tunnel, no problem,” he tells the podcast host Joe Rogan, who is clearly entranced by his vision. “You can go ten thousand feet down if you want.”

A company, Musk explains, is a cybernetic collective of people and machines. Google and all the humans who use Google are part of a giant cybernetic collective. Through our use of Google, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and other online interfaces, all of which share various types of information with each other, we are all programming a giant AI, which will ensure that humans soon represent only a tiny fraction of the functional intelligence on our planet. Elon was a big proponent of heavily regulating the development of AI, he explained, but nobody listened.

“You’re freaking me out,” Rogan says.

“Nobody listened,” Musk repeats.

I look outside again. I notice that the sky has gone dark.

“Years will pass,” Musk intones. “There will be some sort of insight committee. There will be rulemaking. Then, there will be oversight, eventually regulations.”

In the meantime, Elon proposes to modify human beings by adding a brain-computer interface called Neuralink that will allow anyone to achieve superhuman cognition, which sounds freaky but is already more or less here. “Your phone is already an extension of you,” he reasonably points out. “You’re already a cyborg, and most people don’t realize it.” Where the information flow between our biological and our digital selves is currently like a tiny straw, Neuralink aims to make that tiny straw into a giant river. “It’s an interface problem, a data-rate problem,” Musk says.

Human beings live in language, and not outside it. Maybe someday, a technology like Neuralink will allow Elijah to speak, and to better process language, thereby being able to more fully realize his inherent humanity, which now struggles through in fits and starts. I will talk to him, and he will talk back, in complete sentences, mediated by a beneficent machinery. Instead of being marred by flawed connections that turn “come” into “chum” and can’t process strings of more than two or three words at a time, Elijah will architect soaring cathedrals of language, the same way he builds towers out of blocks. As he is able to express himself more fully, I will feel less isolated from my wife, and she from me, and we will embrace the future-present together, as a hopeful story. Maybe, with Elon Musk at the helm, America can still stay America for just a little while longer, and I won’t have to run away to a mountaintop for shelter.

“I know that it’s probably something that the government’s supposed to handle,” Rogan suggests, adding, “I don’t want the government to handle this.”

“Who do you want to handle this?” Musk asks.

“I want you to handle this!” Rogan enthuses.

“Oh, geez,” Musk says, with appropriate modesty. It is his belief that the world we inhabit and take as real is only one of many simulations, all of which are running at the same time. Life outside the simulation is probably pretty boring, like a movie set. Not that it matters. “The universe as we know it will dissipate into a fine mist of cold nothingness eventually,” he concludes. So, in the meantime, why not buy a Tesla?

Rogan wonders what it’s like to be inside Elon Musk’s head.

“It’s like a never-ending explosion,” Musk offers.

“Try to explain it to a dumb person like me,” Rogan urges. “What’s going on?”

“Never-ending explosion,” Musk repeats.

Musk accepts a blunt from Rogan, even though he claims that he generally eschews pot because it’s bad for productivity, “like a cup of coffee in reverse”—an off-the-cuff what-the-hell type of gesture that nearly tanks Tesla’s stock.

It is impossible for me to continue to ignore the change in the weather outside. The picture window has gone nearly black. Still plugged into the podcast on my iPhone, I wander out to see exactly what I am in the middle of. Twin pillars of gray smoke are now looming above the next ridge, just north of my friend’s cabin, in what looks like a scene from a Bible movie. Evidently, I don’t have much time left.

I run inside, throw my clothes and records into a bag, jump into my Mustang and call the Sunset Marquis hotel, which is another place I like to escape to, in the hope that they might still have a room available. They have exactly one room. After paying in advance, I head back up the steep incline of the driveway and onto the twisting canyon roads. There is a three-hour delay on the PCH back to Los Angeles, but the eastern route through the canyons will take a mere 45 minutes, according to Google Maps.

Following the spoken directions, I drive north, along roads that are eerily empty, except for a single Ford Ranger truck, which goes whizzing past me in the opposite direction, doing at least 85. I keep going. A dump truck passes, its sides scorched by fire. Another turn in the road, and I can see the twin pillars of smoke through the canyon directly ahead of me. Google has been leading me straight into the fire.

“Holy fuck!” I curse out loud. “Fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck.” I can think about exactly when I should have realized my mistake later on; what matters now is getting the fuck out of here. In another 45 minutes, I have made it back down to the Pacific Coast Highway, where horses and llamas are gathered on the beach. My heart is still racing.

That night, after three drinks and a large spliff filled with some excellent marijuana, I sit by the pool outside my hotel room and smoke a nighttime cigarette. “This may sound corny, but love is the answer,” Elon Musk is explaining through my headphones. “It’s easy to demonize people, but you’re usually wrong about it. People are nicer than you think.”

Amen to that. America is the green light at the end of the dock. It’s a word for a feeling that will always be with us, producing no end of tragedy and disappointment. Maybe, I think, my family will be safe in New Zealand. Maybe Elon Musk will terraform Mars. Maybe my son will write poems using words he can’t speak. Meanwhile, the wildfires will continue to burn.

Art credit: Max Riché. From the series Paradise, 2020-ongoing. © Maxime Riché. Images courtesy of the artist.

Aerial photo of the Camp Fire, NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey, and MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS/LANCE and GIBS/Worldview.

There’s a cabin in the hills up above Malibu belonging to a Hollywood friend of mine, where I go when I get in the mood to get away from it all. My stated intentions are watching cartoons and sleeping late, though these ambitions are predictably frustrated by the large plate-glass window in the bedroom, which along with its remote but fashionable location is definitely the cabin’s main attraction, offering what was quaintly referred to a generation ago as a million-dollar view—a figure that now has an extra zero or two appended to it, depending on the frequency of fires and mudslides in the area. The window stares directly at the Pacific Ocean, so that if you drew a dotted line directly from the spot where the early morning sun rises over the mountain to the ocean, and then back from the ocean to the window, with only a single large shade between, it hits a sleeper’s eyelids with a luminous flux of painfully literal, godlike intensity. Imagine one of those stop-action diagrams that flash on screen right before Road Runner is blown away by a bazooka.

The rest of the interior space of the cabin—maybe seven hundred square feet, with a kitchen-living room with a four-burner stove—is efficiently engineered, in a way that feels both compact and expansive, though the sheer size of the window means it’s impossible to sleep past sunrise, no matter how tight you draw the curtains. The sunlight reflected off the ocean is so bright that it feels like it is illuminating your eyeballs from within. It’s like God is taking his semiannual X-ray of my soul.

Getting away from it all is pretty much a necessity in my life these days, and I am grateful for the view, even with the early-morning wake-ups, which lack the cortisol-driven urgency of being woken up an hour or two earlier by my youngest son Elijah, who can’t sleep for more than three or four hours in a row, most likely as a result of a stroke suffered at birth. My wife is riven by Elijah’s condition, which is neither terminal nor yet entirely explicable, and has turned her into an unexpected combination of a neuroscientist and Dr. House. In supporting roles are myself, two older children and the menagerie of companionable pets—including two Siberian cats, who hate our new sheepdog puppy, which we purchased as a nod to conventional ideas of childhood joy.

So far, Elijah’s condition affects some large part of his fine-motor abilities, which include the ability to speak more than two or three intelligible words in a row. Speech is among the more complex fine-motor activities on which our humanity is founded, requiring the neural coordination of more than thirty separate muscles in the mouth and tongue. Elijah’s receptive language is at the level of a normal six-year-old, or even above that, according to various forms of more or less sophisticated testing like telling him to “please bring the paper towels to Mama in the kitchen.” (Promise a cookie, and your instruction will be completed more or less immediately.) In addition, Elijah has suffered from focal seizures on the right side of his brain since he was three, especially during sleep, when the brain is more porous and would normally integrate the experiences he has during the day. To control his seizures, Elijah receives varying dosages of medication, which are most likely responsible for his frequent bouts of morning nausea.

Other than that, Elijah is a clever, funny boy who loves his cats and dogs and may or may not gain the ability to speak, or sleep normally, or care for himself. Time will tell whether Elijah will improve or not, and to what degree, and in what ways. Every year he grows older, and stronger, and more physically difficult to manage, even as more of his underlying curiosity and intelligence shines through. Especially late at night, I strain to make sense of words and phrases that clearly have meaning to him but in which syllables are scrambled together in no predictable order. Sometimes I fear that they add up to nothing, or to something less than what I hope. In some branching number of possible universes Elijah will live with me forever, fiercely alive, though mostly mute, as we search for ways to communicate through an unstable aperture that sometimes seems like an open window and then narrows to the width of a straw.

The more selfish parts of my own nature find their own set of coordinates: 34.0259° n, 118.7798° w. I flee there every six months or so in order to write with zero distractions courtesy of my personal Gatsby, who is insanely rich if not quite so lonely as his fictional namesake, and generous in the way of people who get bored quickly with material possessions but not with people. He says he won the cabin in a poker game—which is more or less a true story. The shelter it offers, in which I cut myself off from the sustaining web of people I love and who love me back, helps restore my interdependent self to its original state of splendid isolation, in which I can endeavor at least to make sense of it all.

Hello, Malibu! Alone on a mountaintop, an atomized figment of my own imagination with nothing between the membrane of me-ness and the mirrored vastness of the Pacific Ocean, I can inhabit my own skin for hours if not days at a time. I can make notes on personal and familial suffering, read Latin and Greek, watch cartoons and otherwise do my best to figure things out. My ruler is the classical measure of man, who is himself or herself a reflection of something that is knowable only in relation to others, each of us reflecting back some aspect of the divine. Or else, the miracle of our shared humanity is only a myth, and Elijah is simply a set of mangled circuits.

In the summertime, the heat inside the cabin gets so bad by midday that it’s impossible to think straight; even with both doors open, the fan on and the windows cranked as wide as they can go to achieve maximum cross-ventilation, it takes an ice cube maybe four minutes to melt in a glass of water. The benefits of this particular set of coordinates easily outweigh the costs, though. The view is gorgeous, with no neighbors visible for miles, except for a famous music producer whose white Italian villa and backyard swimming pool are located maybe forty degrees off center from the direct view-line from the window to the ocean. I’ve seen things when I’ve turned my head that way, believe me—I can’t help it, although, to be honest, it’s never been anything wilder than pretty girls lounging by the pool with little or no clothes on, which is a sight that I am grateful for. For the most part, I find Southern California to be a grim, puritanical place, whose much-advertised hedonism is only a surface distraction from an underlying religious tone that is centered on death and involves its own distinctive modes of perversion—ranging from submission and self-denial to black magic and other ritual desecrations of the human imago, like sexual torture. It’s an anything-to-feel-something kind of place.

What I am after up here is nothing quite so extreme. I long ago adopted the post-Enlightenment model of a pleasure-seeking existence rooted in the kicks I get from music, prose aesthetics and recreational drugs, with some atavistic God-seeking mixed in. I also enjoy sweets and fruit. Depending on which way the wind is blowing, I can use my energies to make stuff up, and to wallow in my own being like a libertine hippopotamus, with only a pair of eyes and giant, flaring nostrils visible above the muck.

Still, being alone is hard work, and if you want to make it through the hours and days at least semi-intact, you need to get straight with yourself. This is a useful nugget of philosophy I took with me from the period of my life in which I worked assiduously not to use drugs. Getting straight is a chore, but it breeds its own wisdom. You need to keep looking in the mirror, even when there are plenty of excuses for looking elsewhere. Telling lies will never make you a better person or the world a better place. It is wrong to assent to propositions that you believe to be false, even if that makes you unpopular with people who aren’t really your friends (or else they wouldn’t be inviting you to do drugs). Conspiracy theories are also a kind of drug. Once you assent to the counter-reality that they posit, you forfeit your appeal to the evidence-based methods that tell you whose face is looking back at you. A touch of white hair around the temples, along with a tolerant, knowing gaze and a general tone of health and decorum, especially combined with regular physical exercise, is a better way to orient yourself.

As a writer, moreover, I pride myself on seeing things not just clearly, but early. And what I saw from my loaner cabin in 2019 was the same thing I saw upon my return to the mountain a year later, when the connections between my own drive toward silence and isolation and the combustible nature of my surroundings had become too obvious to ignore.

The wildfires came first. Then came the pandemic, followed by a protest movement whose initial focus on police violence quickly broadened out into a roiling nationwide revival movement emphasizing the omnipresence of racism and other sins whose origins lay deep in America’s past. The fires, the plague, the turmoil on the streets and the sins of America’s past were all real. But the urgency of these problems, whether taken alone or together, didn’t explain why the whole country had been put on tilt. The real message was in the velocity with which generally agreed-upon perceptions and social habits appeared to flip 180 degrees from one week to the next, pressed forward each time by the urgency of the demand to refigure reality.

This sense of a foundational shift had not arisen organically, in response to events. Rather, it was part of the functioning of a new machine, made up of data-driven tools and platforms whose feedback loops had been fashioned according to the addictive logic of corporate advertising. The machinery made it easy for small groups of self-aware agents, whether driven by ideology, or money, or personal appetites for chaos, to rapidly empty out shared, socially defined abstractions like “America” of their familiar meanings and invent in their place new narratives, oriented toward a new future in which “justice” would replace “happiness” as America’s big rock-candy mountain. The failure of these promises would in turn provide more fuel for the machine.

A new country may yet be formed from such operations, but it is unlikely to be called America. That’s because, for the creators of the new American future, “America”—which is a particular kind of human experiment grounded, in its four or five distinct historical incarnations, in the democratic argot celebrated by Walt Whitman, Louis Armstrong, Chuck Berry and other great American poets—is precisely what needs to be undone. The birth of the new un-America is therefore a tragedy, at least according to the Greek idea that fate is inescapable. It is fueled by the same radical individualism, the same determination to inhabit the never-ending future-present, that made the country, for a time, such an inescapable success.

●

To get to my friend’s cabin, I drive up a traffic-choked stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway leading out of Los Angeles, then duck into the third canyon exit after Topanga. Then, guided by Google Maps, I drive up through two canyons and along a series of twisting roads, past homes teetering precariously on the edges of cliffs like stray sprinkles on the side of a burnt-over cupcake. The driveway to the cabin is at a steep incline, such that the house is invisible from the road. I ease my old Mustang nose-down, at a 45-degree angle, until it bottoms out near the garage. I am home free, nearly. Eleven more staggering steps and I can sit down on a bench underneath a tree that provides blessed shade and stare out at the ocean and the music mogul’s swimming pool.

The news on my phone and on the large-screen television inside is all about wildfires, which seems like as good a place as any to start. The state of California is on fire, starting perhaps thirty miles from the cabin and extending as far north as Mendocino. Entire forests are spontaneously combusting, sending rivers of flame down hillsides and into valleys, where they find still more fuel, overwhelming the scarce resources and ingenuity of the firefighters who are heroically withstanding temperatures of 120, 140, 150 degrees Fahrenheit. When the fires get too hot, the firefighters fall back to the next firebreak and hope that the wind shifts or that the fuel supply gets low enough for a line of fire trucks assisted by helicopters and maybe a giant propeller plane, a marvel, to swoop in and douse the edge of the blaze, giving the firefighters some time to catch a breather. Plumes of gray smoke from the fires are visible to the north and west of where I sit.

Fighting wildfires involves young people risking their lives by jumping into flames when every human instinct is telling them to run. This is a kind of heroism that no longer interests the narrative “us,” just as we are, supposedly, no longer interested in fire as a means of appeasing the gods or aiding in purification rituals. What interests us nowadays is the question of who is responsible for the fires—a question as old as Salem but now updated to align with the latest revisions to the American occult. Wildfires are no longer acts of God, or elemental confrontations between man and nature: they testify to the urgency of climate-change models, or symbolize the evil of big power companies, or homeless migrants, or off-the-grid devotees of QAnon.

A case in point: On the morning of November 8, 2018, the previous fall, a seventy-year-old retired jeweler named Don Peck awoke to loud explosive sounds outside his home in Paradise, California. “It was boom, boom, boom,” he recalled later to a reporter. What he heard was the sound of propane tanks exploding as the town caught fire. “It was late in the morning, but it was dark as midnight,” he recalled. Jumping in his Chevy pickup, he made it to the highway to Chico, which was gridlocked. “There were a lot of these little buses that are used to take older folks around. The lights were on in some of them, and they were packed. And I could see that everyone was petrified. No one knew if they were going to get out alive.”

The Camp Fire, the name of the wildfire that ignited the town of Paradise, taking the lives of 85 people, was the most destructive blaze in California state history, more than three times as deadly as the Tubbs Fire, which had consumed five thousand buildings with 22 dead the previous year. “The scale was astounding,” said Scott Stephens, a professor of fire science at UC Berkeley and an expert on wildfires. “You essentially lost a whole town.”

In its “very meticulous and thorough” investigation of the Camp Fire, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection found a clear culprit: Pacific Gas & Electric, one of the state’s largest and most hated utility providers, which filed for bankruptcy in January 2019, citing an estimated thirty billion dollars in fire-related liabilities. The Cal Fire report provided an entirely coherent explanation for how the fire started and spread; the investigators even furnished photographs of a rusty metal hook whose failure had allowed a PG&E power line to ignite the blaze. Yet if the charge was in fact true, the report was still misleading in a way that would become part of a pattern of simplistic scapegoating and blame-mongering in wider media narratives, deflecting attention and energy away from the kinds of systemic solutions needed to actually help prevent future fires. The implication in the coverage of the Camp Fire was that the broken metal hook and other particulars painstakingly documented in the report were unique or unusual occurrences. In fact, failing PG&E power lines had caused more than 1,500 wildfires in California over the past six years alone—most recently the Dixie Fire, which was sparked this July only a few miles from where the Camp Fire began.

With each destructive fire, the media looks for new culprits, their attention wavering between corporate villains and human ones. The Holy Fire, which burned around 23,000 acres near Lake Elsinore, was ostensibly the fault of one Forrest Gordon Clark, an Orange County man who had expressed support for what the press called “alt-right conspiracy theories” on his personal Facebook page. The posts, uncovered by J. J. MacNab, a Forbes columnist who writes on right-wing extremism, included a couple about Agenda 21—a fringe theory that posits that nefarious politicians and environmentalists are behind the fires. Others were in support of the QAnon conspiracy theory, an elaborate multiplayer participatory role-playing game whose apparent premise was that President Donald J. Trump was secretly orchestrating a day of reckoning for elite pedophiles, under cover of the Special Counsel investigation led by former FBI Director Robert Mueller. It is not clear how any of these posts incriminated Clark; nevertheless, he remains in jail to this day awaiting trial, unable to make his million-dollar bail, even as the lead investigator in the case has acknowledged under questioning from Clark’s attorney that there were at least two other possible causes of the fire, and that he “made a mistake” in identifying where it started in his initial report. Clark himself claims to have no clear memories of the day the fire started, and has blamed both his neighbors—one of whom was a volunteer firefighter—and “Mexicans” for igniting the blaze.

Focusing on the particulars of any one fire had the advantage of allowing investigators to focus on discrete causes that, presumably, could be addressed with better planning, regulation or (in Clark’s case) comprehensive surveillance of U.S. citizens and residents based on their personal belief systems and mental-health statuses. Yet the costs of these solutions were rarely accounted for. In order to keep power lines from sparking in dry, windy conditions, for example, PG&E began routinely cutting power to millions of Californians—who over decades had decided it was safe to locate homes in formerly wild or thinly populated areas, which were duly connected to power grids and to the state’s enviable system of roads. After the Kincade Fire destroyed 78,000 acres of California wine country, forcing 180,000 people to evacuate their homes, the power cuts caused millions more Californians, many of them elderly or otherwise vulnerable, to go without electricity in the broiling heat.

As the search for a culprit for seasonal wildfires continued, the press predictably turned to Donald Trump—attacking the president’s refusal to publicly acknowledge what the AP referred to as “the scientific consensus that climate change is playing a central role in historic West Coast infernos.” If Trump or his batty supporters weren’t starting the fires themselves, a deluge of reports suggested, they were responsible for bringing on the catastrophe by failing to pay proper obeisance to the science gods.