“The ice-cream machine will shortly be shut off for cleaning,” said the voice on the loudspeaker. The walls were beige and the chairs were beige and the plants were fake. It smelled like a college lunch hall in summer. After the announcement the hall started to fill with something that sounded like stone tearing, but was actually chairs grinding across tile. One by one, the delegates got up and lurched over to the ice-cream machine before it was shut off, looking like tired pilgrims from another millennium queuing up to touch the bones of a dead saint. Ice cream flowed into their bowls like a stream of miracles.

Every year, three thousand people gather in Kalamazoo for the sake of the years 400 to 1400 (approximately) of the Common Era. The International Congress on Medieval Studies, held annually at Western Michigan University, is the largest gathering of medievalists on earth. They come from all over the world to participate in panels like “Attack and Counterattack: The Embattled Frontiers of Medieval Iberia,” “Waste Studies: Excrement in the Middle Ages,” “Historical, Ethnical and Religious Roots of the Thraco-Geto-Dacians and Their Successors: Romanians and Vlaho-Romanians” and “J. K. Rowling’s Medievalism (I & II).” They are literary critics, historians, experts in numismatics and linguistic datasets, and nuns. There are over five hundred sessions: meetings and drinks parties and bookstalls; groups of monks dressed in black; bespectacled, serious, young men; elderly ladies in capped sleeves. Here is a ragtag bunch of human beings all on the same pilgrimage, playing a part in a story that they can’t read, because they’re in it.

In Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, a group of pilgrims have a tale-telling competition on the way to Canterbury. Boccaccio’s Decameron has a similar structure: a group of young men and women are holed up in a house outside Florence to avoid the plague, telling tales to pass the time. Those works are both from fourteenth-century Europe, but the “frame story” format has been popular for a long time in many places. Sanskrit epics the Mahabharata and the Ramayana are also organized in this way. So is the Arabic One Thousand and One Nights. The frame story is a great structure for a lot of reasons, but one of them is that actual life is kind of like this. We pinball between reasons for being places, with people: weddings, funerals, vacations, school, swimming lessons, medieval conferences in Kalamazoo.

The Canterbury Tales technically takes place on the grounds of a pilgrimage, although the actual stories veer between courtly chivalric romance, religious treatise, crude fabliau starring naked ladies and so on. Chaucer explains in the Prologue that people like to go on pilgrimages in “Aprill,” when soft showers have sweetened the “droghte of March,” causing the pretty flowers to grow and the birds to sing. People go on pilgrimages, he tells us, for God and for fun. The conflict between religious and secular modes of acting and speaking continues throughout The Canterbury Tales. This makes the work fun to read, but it also disjoints its premise from its content. It’s a book of religious pilgrims telling stories about branding asses with hot pokers. But that’s fine, because having fun is at least half the point. In fact, the consistent mixture of edification and entertainment brings a kind of unity to the work.

If you understand this, you understand the International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo. Medievalists, who lead solitary and difficult lives, with only books for friends, get together and cavort and dance and talk about the things they love the most in the world, surrounded by people who care about the same things they care about. The frame holds together a vast tangle of contradictory stories—a thousand academic papers, a thousand combative Q&As, a thousand awkward wine receptions—with the glue of a ferocious and shared love for the deep, deep past. As with Chaucer, however, that doesn’t mean anybody actually understands what’s going on.

●

I gave my paper in an over-heated classroom as part of a panel called “Of Whom Shall I Be Afraid?” One of the male delegates spoke for too long, as happens on every panel. But at least by this point I had made some new friends. There’s this group of guys known to some as the “Bromance of the Rose,” which is a hilarious medieval joke based on the name of Le Roman de la Rose (“The Romance of the Rose”), one of the most enormous allegorical dream vision poems. The Bromance, my new friends, put together an astounding panel dedicated to it.

Have you ever fallen in love through a screen? I’m sure you have, at least a little. That’s what my favorite part of Le Roman de la Rose is about. It’s from the section by Guillaume de Lorris. (There’s another section written by Jean de Meun, who finished it after Guillaume died around 1240.) When the dreamer (the poem’s protagonist) falls in love with a rosebud, it happens out of the corner of his eye, in a reflected image. He has fallen asleep and, dreaming, comes across a walled garden. He finds a tiny door in the wall and knocks. Admitted by Idleness, the dreamer finds himself in a garden flush with May.

The dreamer wanders and meets people in this garden. Then he finds the spring. No innocent font (no fons Bandusiae), this is the pool into which Narcissus also gazed. The poem goes on: “With great mastery Nature had situated the fountain within a marble stone under the pine, and on the stone were written, on the upper edge, little letters which said, ‘On this spot died beautiful Narcissus.’” Then, there it is! A rosebud, reflected.

The dreamer catches sight of the rosebud and falls in love with it, leading to the action in the rest of the poem. But the fountain’s mirroring surface wavers and ripples—there is something behind it. At the bottom of the fountain, two deep channels swirl around two crystals reflecting light, which reveal the whole being of the orchard, as it really is, to the person who gazes into the water. Like a big machine of perception, the fountain takes in light bouncing off a rosebud and gives back a love object—the whole being of the orchard. The rosebud is therefore seen reflected, mirrored, deferred, mediated and speculated upon.

Isn’t this just exactly true? The object of desire is always first glimpsed partially, by accident and while one is thinking primarily of oneself—a square on a screen, a chair at a classroom corner, a haircut disappearing between party guests. We always fall in love with the image of the thing before the thing itself. But does that lessen the truth of our love? You can’t rely on your senses to tell you the whole truth, but you might as well enjoy the orchard.

While giving his paper, one of my new friends talked about Cupid distributing seeds on the surface of the fountain of the Le Roman de la Rose in a certain erotic passage that I have forgotten. My notes from his talk are as follows:

Johnny posits that Cupid has been masturbating into the fountain in the RDLR: the fountain can be read as an eye. Cupid ejaculating in the eye (whose eye?). Reread.

At the disco, later, one member of the Bromance insisted that he had been attacked by a squirrel that day, or, as he put it, “aggressed by a wer-squirrel.” This was funny to me because “wer” is Old English for man. About halfway through one of my sad circuits around that disco hall, I looked back over the day’s events, and then over the past year, and then over the past decade. I saw a red-bearded scholar in a Hawaiian shirt plunge his face into a basin of ice holding free beers. I wheeled around and saw a head of department sweatily grinding against another delegate. From a white-clothed table a woman in a suit and thick glasses was glaring at me with real hatred. From a white-clothed bar a very old man was eyeing me hungrily.

I felt myself to be seen reflected, mirrored, deferred, mediated and speculated upon. Here were problems of seeing, knowing, loving and danger. This is not my garden, I thought to myself. This is not my dream vision. If this is somebody else’s dream, how can I get out of it? Of whom shall I be afraid?

●

The Venerable Bede was a cleric and historian, one of the greatest of all time. He wrote the Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (“The Ecclesiastical History of the English People”), which was so good that for a long time historians after him basically just repeated what he said. He finished it when he was just knocking on sixty, in the year 731. In recognition of his remarkable life and contribution, in 1899 Bede was made a Doctor of the Church by Pope Leo XIII. He remains the only British-born person ever to hold such a position.

The Historia Ecclesiastica is essentially the first big book of continuously told history about English people. Written in Latin but later partly translated into Old English (the language of Beowulf), the book starts in 55 BCE with Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britain and ends in the “present day.” In a lot of ways, it reads like a doctoral dissertation: Bede, having opted out of normal human society, wrote an apparently objective history so that he and his contemporaries could better understand the world and their place in it.

Bede died hundreds of years ago but the place he lived, Jarrow, still exists. Jarrow is way up in the northeast of England. On Jarrow’s Wikipedia page, you see it on a map of Tyne and Wear, kind of in an analogous position on the screen to Tyne and Wear’s own location in the country. Its jagged outline gloms onto the upper right-hand part of England like a tattoo on a shoulder.

Somewhere beneath that on the Wikipedia page, Bede’s name lies under Roger Avon’s, like this:

• Roger Avon, actor

• Bede, Benedictine monk and scholar

You may remember Roger Avon from 1972’s Au Pair Girls, or Daleks – Invasion Earth: 2150 AD (1966). I think it’s funny that Daleks – Invasion Earth is only set 134 years in the future, while Bede lived ten times as long ago as that. There are only two women on the list of famous Jarrow residents. The majority of the people on the list are footballers and musicians. Among them are Wee Georgie Wood, the music-hall star Paul Thompson, who played the drums in Roxy Music, and Sunderland Football Club goalkeeper Jimmy Thorpe.

George Wood was better known as Wee Georgie Wood because he was a little person and “worked most his professional life in the guise of a child.” The second paragraph of his page begins “Wood, who, when fully grown, was 4 ft 9 in.” George is mentioned at the end of the Beatles’s “Dig It,” one of the worst songs on Let It Be, their worst album. On the West Coast of Tasmania there is a model railway named “Wee Georgie Wood Railway” because it is small, as was Wee Georgie Wood. When Paul Thompson was a teenager, he played in a band called the Urge. “Tiredness from performing with them seven nights a week in local clubs and pubs led him to fall asleep on his job as an apprentice metalworker, which resulted in his dismissal,” reads his Wikipedia page. Thompson is now in a band called the Metaphors.

Jimmy Thorpe died after being kicked in the head and chest during a match against Chelsea. It was a few days later that he actually slipped behind the veil separating the mortal and the spiritual Jarrows, but on the town’s Wikipedia page Jimmy is memorialized as having “lost his life helping the club win the 1936 League title.” Footballing Jarrow’s other great son, David Hague, might be a bit more famous, but his Wikipedia page ends: “After playing for the Portland, where Hague was nominated for rookie of the year, Hague went to Uruguay to play for Danubio F.C. It was decided that Soccer did not deserve David and he quit instead.[citation needed]” Jimmy Thorpe never quit instead.

Whether or not the Venerable Bede’s character was informed by an immutable spirit of Jarrow, we can never know. It’s cold up there, teetering on the North Sea. I don’t believe that my personality is determined by the place I was born, but I must be at least a little bit worried that it could be true, because otherwise I wouldn’t have made it the subject of my paper at Kalamazoo.

I was trying to figure out how the particular tropes of racism and nationalism (two sides of the same coin) came to be how they are. “Environmental determinism” and “geographical determinism” are some terms you can use to refer to the idea that the place you’re born in (the weather, the location, which of Noah’s sons founded your continent, etc.) has an effect on your inner life. Racists tend to believe it, because it suggests that people are different from each other in some essential way. Anyway, perhaps in another time Bede could have been the one to administer the tick-tock time-bomb pelvic beat to “Love is the Drug.” Maybe he could have taken footballs slick with cold mud to the face (with a slap) and groin (with a thud). We’ll never know. Instead, Bede spent his life in a Benedictine monastery, presumably never having sex or drinking or playing football or drums. He grew up to be a hero anyway, and maybe that’s the spirit of Jarrow: one hero every thousand years.

●

The history of Jarrow’s sons may show us that Bede is only one local champion among many, but his talent matched the greatest of his neighbors. The Venerable Bede never played in the Metaphors, but the figure he invented to describe the human lifespan has haunted me since I first read it, sleepy and floppy with hangover in my university halls room, which was full of red carnations jammed into empty wine bottles. Here’s my translation:

It seems to me, your majesty, that the life human beings have on earth now, when you see it in relation to everything we don’t know about, is like this: You are sitting having supper in winter with all your advisors and commanders, a nice fire burning, while outside storms of rain and snow are raging. A sparrow flies swiftly through the room. In one door, out the other. While the sparrow is inside, the winter storm cannot hurt him. But after a little space of comfort, he soon returns to the wintry winter, out of your sight. In the same way, the life of human beings is only visible to us for a short time: what happens next, or what happened before, we just don’t know.

I first read these lines during my first year at university. It had got so cold so quickly—one day I was moving in, asking the girls on my corridor if my outfit for the first night’s formal dinner was okay, then it was winter. I brought a lot of stuff with me, records and an easel and so on. Ioanna’s room was across the courtyard and I could wave to her through the window.

We who are on earth today live out the figurative second in a sparrow’s life as its body moves from one window to the other. We don’t remember where we were and we can’t see out the dark window (since it is so bright in here) to predict where our flight path will take us. That feeling of being protected from the weather outside is real—when I was a kid my bedroom was in the attic, and my bed was under sloping windows, so when it rained I could look straight up into the weather my body didn’t have to experience, and feel happy. But, safe from the wintry storm, the tempestas, we who shelter in here don’t understand much at all.

I thought all that about the swift flight of the sparrow and put the library book down. It clanged around in my brain for a minute, banging into the sad Old English poems about exile and my ambivalent feelings about the bits of Boethius sitting in a box in Pavia. Then it drifted down and settled on the ocean floor of my interior life. I’d been staring straight ahead at the basin that was bolted to the wall at the foot of my bed for a few seconds, but now I put on my boots and blue coat and headphones and walked around Oxford for a while. First I walked around Radcliffe Square, which is profoundly cobbled. Then I walked over to Broad Street, down to Longwall and then to the Cowley roundabout. Those roads just have ordinary pavements that are normal to walk on.

Trudging around in the dark, I was clueless but electrified. Bede had made me feel like an idiot, but his sparrow clarified for me the relationship between my body and time. This flesh—absurd puppet! I woke up that morning in 2007. Big deal. How many eyes opened on a day like, say, July 26, 1158, in any given city, let’s say Munich? We tick off months and paychecks and paint parts of our bodies and our skin droops. We are sweet animals, but there have been so very many of us. You’re less than a grain of rice in a thousand swimming pools of rice. All of which is to say that Bede’s sparrow is a very appealing kind of thought to both a medieval religious person and a sad twenty-year-old just after the turn of the next millennium. That was how my dream vision began.

●

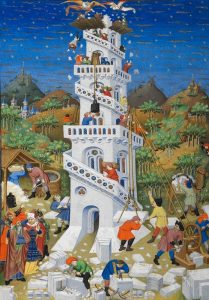

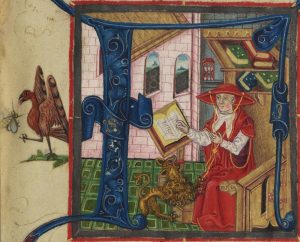

In a tapestry or manuscript illumination depicting an allegorical scene, it is common to find labels hovering over people’s heads. A person might be labeled “Avarice,” for example. These labels are a guide to the kind of symbolism called personification allegory: each character represents an idea, then they behave so as to illuminate the principle they embody. In allegory everything seen is mirrored, deferred and relative.

Across Kalamazoo, labels and signs hovered everywhere. After giving my paper, I went for a solitary little wander. At the end of one corridor I found, taped to the glass part of a door, a piece of paper advertising an event called “SO YOU THINK YOU CAN CHANT,” which promised attendees “An EnCHANTed Evening.” Drawn to the sign, I reached out to touch it and ended up opening the door it was attached to. On the other side of the door, a cavern of wonders! Here was the big exhibition hall, where all the scholarly presses, little-crystal vendors (one stall was named “THE CURIOUS LOVE OF PRECIOUS STONES”) and medieval music-makers flog their wares.

Sloping around the corner of the maze-like exhibition hall, I came upon a nice-faced lady sitting beside an elderly man in a large and very elegant white hat. Their stall was selling jig music. When I asked if they would mind if I took a photograph of their sign, the lady smiled gently and said, “Spread the word!” So here I am telling you about it. Perhaps you too will stumble over them, some day.

And then there are the books—I can’t even tell you how many books there were. Just think: How many pages, how many footnotes? How long would the index be if there were an index of every book sitting in that room? Maybe it would stretch around the world, or back to the Norman Conquest. Maybe the number would be so staggeringly high that we’d all get dizzy and give up our quests—the job would seem like too much.

Up and down the aisles I went, agog at the things for sale. At one stall, an advertisement was blown up on a massive bit of cardboard, blaring “THE SAINT AND THE CHOPPED-UP BABY.” This advertised a book about a Spanish man named Vincent Ferrer who lived from 1350 to 1419 CE. He was canonized while still alive, which seems contrary to the spirit of these things. The chopped-up baby refers to his best miracle. As the back-cover blurb puts it, “Vincent came to be epitomized by a singularly arresting miracle tale in which a mother kills, chops up, and cooks her own baby, only to have the child restored to life by the saint’s intercession.” Vincent is pictured next to a baby that has been dismembered into a pile of limbs in the painting on the book’s cover. Good thing for the baby that Vincent came along, I suppose. I had no interest in this book beyond its cover, so I moved on. It was late afternoon, I was hungry. In the cafeteria beside the exhibition hall there were sandwiches for sale labeled “Medieval PB&J.”

All these pieces of paper with words on them: What did they mean? Probably no allegory is legible to those participating in it: the characters named Envye or Scripture do not know why they act how they act. The protagonists of tales set within frame narratives do not see themselves as part of the whole. They—we—just do.

Religious people have an easier time with mysteries of this type, and Western people were certainly more religious in the Middle Ages than they are today. Faith is gone now, but the mysteries remain, animating the days of some of the living with a thirst for understanding so desperate that it cannot be diminished even by conference discos. Perhaps we won’t figure any of it out. I’m sure the vast majority of us will never discover anything useful at all. But individual words can be transcribed from manuscripts and individual references can be chased down. That will do for now. It is not for the sparrow to know what lies beyond the hall, and anyway—what’s the hurry?

“The ice-cream machine will shortly be shut off for cleaning,” said the voice on the loudspeaker. The walls were beige and the chairs were beige and the plants were fake. It smelled like a college lunch hall in summer. After the announcement the hall started to fill with something that sounded like stone tearing, but was actually chairs grinding across tile. One by one, the delegates got up and lurched over to the ice-cream machine before it was shut off, looking like tired pilgrims from another millennium queuing up to touch the bones of a dead saint. Ice cream flowed into their bowls like a stream of miracles.

Every year, three thousand people gather in Kalamazoo for the sake of the years 400 to 1400 (approximately) of the Common Era. The International Congress on Medieval Studies, held annually at Western Michigan University, is the largest gathering of medievalists on earth. They come from all over the world to participate in panels like “Attack and Counterattack: The Embattled Frontiers of Medieval Iberia,” “Waste Studies: Excrement in the Middle Ages,” “Historical, Ethnical and Religious Roots of the Thraco-Geto-Dacians and Their Successors: Romanians and Vlaho-Romanians” and “J. K. Rowling’s Medievalism (I & II).” They are literary critics, historians, experts in numismatics and linguistic datasets, and nuns. There are over five hundred sessions: meetings and drinks parties and bookstalls; groups of monks dressed in black; bespectacled, serious, young men; elderly ladies in capped sleeves. Here is a ragtag bunch of human beings all on the same pilgrimage, playing a part in a story that they can’t read, because they’re in it.

In Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, a group of pilgrims have a tale-telling competition on the way to Canterbury. Boccaccio’s Decameron has a similar structure: a group of young men and women are holed up in a house outside Florence to avoid the plague, telling tales to pass the time. Those works are both from fourteenth-century Europe, but the “frame story” format has been popular for a long time in many places. Sanskrit epics the Mahabharata and the Ramayana are also organized in this way. So is the Arabic One Thousand and One Nights. The frame story is a great structure for a lot of reasons, but one of them is that actual life is kind of like this. We pinball between reasons for being places, with people: weddings, funerals, vacations, school, swimming lessons, medieval conferences in Kalamazoo.

The Canterbury Tales technically takes place on the grounds of a pilgrimage, although the actual stories veer between courtly chivalric romance, religious treatise, crude fabliau starring naked ladies and so on. Chaucer explains in the Prologue that people like to go on pilgrimages in “Aprill,” when soft showers have sweetened the “droghte of March,” causing the pretty flowers to grow and the birds to sing. People go on pilgrimages, he tells us, for God and for fun. The conflict between religious and secular modes of acting and speaking continues throughout The Canterbury Tales. This makes the work fun to read, but it also disjoints its premise from its content. It’s a book of religious pilgrims telling stories about branding asses with hot pokers. But that’s fine, because having fun is at least half the point. In fact, the consistent mixture of edification and entertainment brings a kind of unity to the work.

If you understand this, you understand the International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo. Medievalists, who lead solitary and difficult lives, with only books for friends, get together and cavort and dance and talk about the things they love the most in the world, surrounded by people who care about the same things they care about. The frame holds together a vast tangle of contradictory stories—a thousand academic papers, a thousand combative Q&As, a thousand awkward wine receptions—with the glue of a ferocious and shared love for the deep, deep past. As with Chaucer, however, that doesn’t mean anybody actually understands what’s going on.

●

I gave my paper in an over-heated classroom as part of a panel called “Of Whom Shall I Be Afraid?” One of the male delegates spoke for too long, as happens on every panel. But at least by this point I had made some new friends. There’s this group of guys known to some as the “Bromance of the Rose,” which is a hilarious medieval joke based on the name of Le Roman de la Rose (“The Romance of the Rose”), one of the most enormous allegorical dream vision poems. The Bromance, my new friends, put together an astounding panel dedicated to it.

Have you ever fallen in love through a screen? I’m sure you have, at least a little. That’s what my favorite part of Le Roman de la Rose is about. It’s from the section by Guillaume de Lorris. (There’s another section written by Jean de Meun, who finished it after Guillaume died around 1240.) When the dreamer (the poem’s protagonist) falls in love with a rosebud, it happens out of the corner of his eye, in a reflected image. He has fallen asleep and, dreaming, comes across a walled garden. He finds a tiny door in the wall and knocks. Admitted by Idleness, the dreamer finds himself in a garden flush with May.

The dreamer wanders and meets people in this garden. Then he finds the spring. No innocent font (no fons Bandusiae), this is the pool into which Narcissus also gazed. The poem goes on: “With great mastery Nature had situated the fountain within a marble stone under the pine, and on the stone were written, on the upper edge, little letters which said, ‘On this spot died beautiful Narcissus.’” Then, there it is! A rosebud, reflected.

The dreamer catches sight of the rosebud and falls in love with it, leading to the action in the rest of the poem. But the fountain’s mirroring surface wavers and ripples—there is something behind it. At the bottom of the fountain, two deep channels swirl around two crystals reflecting light, which reveal the whole being of the orchard, as it really is, to the person who gazes into the water. Like a big machine of perception, the fountain takes in light bouncing off a rosebud and gives back a love object—the whole being of the orchard. The rosebud is therefore seen reflected, mirrored, deferred, mediated and speculated upon.

Isn’t this just exactly true? The object of desire is always first glimpsed partially, by accident and while one is thinking primarily of oneself—a square on a screen, a chair at a classroom corner, a haircut disappearing between party guests. We always fall in love with the image of the thing before the thing itself. But does that lessen the truth of our love? You can’t rely on your senses to tell you the whole truth, but you might as well enjoy the orchard.

While giving his paper, one of my new friends talked about Cupid distributing seeds on the surface of the fountain of the Le Roman de la Rose in a certain erotic passage that I have forgotten. My notes from his talk are as follows:

At the disco, later, one member of the Bromance insisted that he had been attacked by a squirrel that day, or, as he put it, “aggressed by a wer-squirrel.” This was funny to me because “wer” is Old English for man. About halfway through one of my sad circuits around that disco hall, I looked back over the day’s events, and then over the past year, and then over the past decade. I saw a red-bearded scholar in a Hawaiian shirt plunge his face into a basin of ice holding free beers. I wheeled around and saw a head of department sweatily grinding against another delegate. From a white-clothed table a woman in a suit and thick glasses was glaring at me with real hatred. From a white-clothed bar a very old man was eyeing me hungrily.

I felt myself to be seen reflected, mirrored, deferred, mediated and speculated upon. Here were problems of seeing, knowing, loving and danger. This is not my garden, I thought to myself. This is not my dream vision. If this is somebody else’s dream, how can I get out of it? Of whom shall I be afraid?

●

The Venerable Bede was a cleric and historian, one of the greatest of all time. He wrote the Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (“The Ecclesiastical History of the English People”), which was so good that for a long time historians after him basically just repeated what he said. He finished it when he was just knocking on sixty, in the year 731. In recognition of his remarkable life and contribution, in 1899 Bede was made a Doctor of the Church by Pope Leo XIII. He remains the only British-born person ever to hold such a position.

The Historia Ecclesiastica is essentially the first big book of continuously told history about English people. Written in Latin but later partly translated into Old English (the language of Beowulf), the book starts in 55 BCE with Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britain and ends in the “present day.” In a lot of ways, it reads like a doctoral dissertation: Bede, having opted out of normal human society, wrote an apparently objective history so that he and his contemporaries could better understand the world and their place in it.

Bede died hundreds of years ago but the place he lived, Jarrow, still exists. Jarrow is way up in the northeast of England. On Jarrow’s Wikipedia page, you see it on a map of Tyne and Wear, kind of in an analogous position on the screen to Tyne and Wear’s own location in the country. Its jagged outline gloms onto the upper right-hand part of England like a tattoo on a shoulder.

Somewhere beneath that on the Wikipedia page, Bede’s name lies under Roger Avon’s, like this:

You may remember Roger Avon from 1972’s Au Pair Girls, or Daleks – Invasion Earth: 2150 AD (1966). I think it’s funny that Daleks – Invasion Earth is only set 134 years in the future, while Bede lived ten times as long ago as that. There are only two women on the list of famous Jarrow residents. The majority of the people on the list are footballers and musicians. Among them are Wee Georgie Wood, the music-hall star Paul Thompson, who played the drums in Roxy Music, and Sunderland Football Club goalkeeper Jimmy Thorpe.

George Wood was better known as Wee Georgie Wood because he was a little person and “worked most his professional life in the guise of a child.” The second paragraph of his page begins “Wood, who, when fully grown, was 4 ft 9 in.” George is mentioned at the end of the Beatles’s “Dig It,” one of the worst songs on Let It Be, their worst album. On the West Coast of Tasmania there is a model railway named “Wee Georgie Wood Railway” because it is small, as was Wee Georgie Wood. When Paul Thompson was a teenager, he played in a band called the Urge. “Tiredness from performing with them seven nights a week in local clubs and pubs led him to fall asleep on his job as an apprentice metalworker, which resulted in his dismissal,” reads his Wikipedia page. Thompson is now in a band called the Metaphors.

Jimmy Thorpe died after being kicked in the head and chest during a match against Chelsea. It was a few days later that he actually slipped behind the veil separating the mortal and the spiritual Jarrows, but on the town’s Wikipedia page Jimmy is memorialized as having “lost his life helping the club win the 1936 League title.” Footballing Jarrow’s other great son, David Hague, might be a bit more famous, but his Wikipedia page ends: “After playing for the Portland, where Hague was nominated for rookie of the year, Hague went to Uruguay to play for Danubio F.C. It was decided that Soccer did not deserve David and he quit instead.[citation needed]” Jimmy Thorpe never quit instead.

Whether or not the Venerable Bede’s character was informed by an immutable spirit of Jarrow, we can never know. It’s cold up there, teetering on the North Sea. I don’t believe that my personality is determined by the place I was born, but I must be at least a little bit worried that it could be true, because otherwise I wouldn’t have made it the subject of my paper at Kalamazoo.

I was trying to figure out how the particular tropes of racism and nationalism (two sides of the same coin) came to be how they are. “Environmental determinism” and “geographical determinism” are some terms you can use to refer to the idea that the place you’re born in (the weather, the location, which of Noah’s sons founded your continent, etc.) has an effect on your inner life. Racists tend to believe it, because it suggests that people are different from each other in some essential way. Anyway, perhaps in another time Bede could have been the one to administer the tick-tock time-bomb pelvic beat to “Love is the Drug.” Maybe he could have taken footballs slick with cold mud to the face (with a slap) and groin (with a thud). We’ll never know. Instead, Bede spent his life in a Benedictine monastery, presumably never having sex or drinking or playing football or drums. He grew up to be a hero anyway, and maybe that’s the spirit of Jarrow: one hero every thousand years.

●

The history of Jarrow’s sons may show us that Bede is only one local champion among many, but his talent matched the greatest of his neighbors. The Venerable Bede never played in the Metaphors, but the figure he invented to describe the human lifespan has haunted me since I first read it, sleepy and floppy with hangover in my university halls room, which was full of red carnations jammed into empty wine bottles. Here’s my translation:

I first read these lines during my first year at university. It had got so cold so quickly—one day I was moving in, asking the girls on my corridor if my outfit for the first night’s formal dinner was okay, then it was winter. I brought a lot of stuff with me, records and an easel and so on. Ioanna’s room was across the courtyard and I could wave to her through the window.

We who are on earth today live out the figurative second in a sparrow’s life as its body moves from one window to the other. We don’t remember where we were and we can’t see out the dark window (since it is so bright in here) to predict where our flight path will take us. That feeling of being protected from the weather outside is real—when I was a kid my bedroom was in the attic, and my bed was under sloping windows, so when it rained I could look straight up into the weather my body didn’t have to experience, and feel happy. But, safe from the wintry storm, the tempestas, we who shelter in here don’t understand much at all.

I thought all that about the swift flight of the sparrow and put the library book down. It clanged around in my brain for a minute, banging into the sad Old English poems about exile and my ambivalent feelings about the bits of Boethius sitting in a box in Pavia. Then it drifted down and settled on the ocean floor of my interior life. I’d been staring straight ahead at the basin that was bolted to the wall at the foot of my bed for a few seconds, but now I put on my boots and blue coat and headphones and walked around Oxford for a while. First I walked around Radcliffe Square, which is profoundly cobbled. Then I walked over to Broad Street, down to Longwall and then to the Cowley roundabout. Those roads just have ordinary pavements that are normal to walk on.

Trudging around in the dark, I was clueless but electrified. Bede had made me feel like an idiot, but his sparrow clarified for me the relationship between my body and time. This flesh—absurd puppet! I woke up that morning in 2007. Big deal. How many eyes opened on a day like, say, July 26, 1158, in any given city, let’s say Munich? We tick off months and paychecks and paint parts of our bodies and our skin droops. We are sweet animals, but there have been so very many of us. You’re less than a grain of rice in a thousand swimming pools of rice. All of which is to say that Bede’s sparrow is a very appealing kind of thought to both a medieval religious person and a sad twenty-year-old just after the turn of the next millennium. That was how my dream vision began.

●

In a tapestry or manuscript illumination depicting an allegorical scene, it is common to find labels hovering over people’s heads. A person might be labeled “Avarice,” for example. These labels are a guide to the kind of symbolism called personification allegory: each character represents an idea, then they behave so as to illuminate the principle they embody. In allegory everything seen is mirrored, deferred and relative.

Across Kalamazoo, labels and signs hovered everywhere. After giving my paper, I went for a solitary little wander. At the end of one corridor I found, taped to the glass part of a door, a piece of paper advertising an event called “SO YOU THINK YOU CAN CHANT,” which promised attendees “An EnCHANTed Evening.” Drawn to the sign, I reached out to touch it and ended up opening the door it was attached to. On the other side of the door, a cavern of wonders! Here was the big exhibition hall, where all the scholarly presses, little-crystal vendors (one stall was named “THE CURIOUS LOVE OF PRECIOUS STONES”) and medieval music-makers flog their wares.

Sloping around the corner of the maze-like exhibition hall, I came upon a nice-faced lady sitting beside an elderly man in a large and very elegant white hat. Their stall was selling jig music. When I asked if they would mind if I took a photograph of their sign, the lady smiled gently and said, “Spread the word!” So here I am telling you about it. Perhaps you too will stumble over them, some day.

And then there are the books—I can’t even tell you how many books there were. Just think: How many pages, how many footnotes? How long would the index be if there were an index of every book sitting in that room? Maybe it would stretch around the world, or back to the Norman Conquest. Maybe the number would be so staggeringly high that we’d all get dizzy and give up our quests—the job would seem like too much.

Up and down the aisles I went, agog at the things for sale. At one stall, an advertisement was blown up on a massive bit of cardboard, blaring “THE SAINT AND THE CHOPPED-UP BABY.” This advertised a book about a Spanish man named Vincent Ferrer who lived from 1350 to 1419 CE. He was canonized while still alive, which seems contrary to the spirit of these things. The chopped-up baby refers to his best miracle. As the back-cover blurb puts it, “Vincent came to be epitomized by a singularly arresting miracle tale in which a mother kills, chops up, and cooks her own baby, only to have the child restored to life by the saint’s intercession.” Vincent is pictured next to a baby that has been dismembered into a pile of limbs in the painting on the book’s cover. Good thing for the baby that Vincent came along, I suppose. I had no interest in this book beyond its cover, so I moved on. It was late afternoon, I was hungry. In the cafeteria beside the exhibition hall there were sandwiches for sale labeled “Medieval PB&J.”

All these pieces of paper with words on them: What did they mean? Probably no allegory is legible to those participating in it: the characters named Envye or Scripture do not know why they act how they act. The protagonists of tales set within frame narratives do not see themselves as part of the whole. They—we—just do.

Religious people have an easier time with mysteries of this type, and Western people were certainly more religious in the Middle Ages than they are today. Faith is gone now, but the mysteries remain, animating the days of some of the living with a thirst for understanding so desperate that it cannot be diminished even by conference discos. Perhaps we won’t figure any of it out. I’m sure the vast majority of us will never discover anything useful at all. But individual words can be transcribed from manuscripts and individual references can be chased down. That will do for now. It is not for the sparrow to know what lies beyond the hall, and anyway—what’s the hurry?

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.