Raritan—the all-American literary quarterly of a pre-internet world—closed its doors last spring, ending a nearly half-century run of literature, politics, art and cultural criticism. It passed with a soft sigh, a sound almost inaudible unless you’d been listening for it. Truth be told, when I heard that Raritan was shuttering, I was surprised it was still around at all.

I learned to read, as it were, from Raritan. I first encountered it the way many young readers come to early polestars—through a high school English teacher. We had been discussing J. M. Coetzee’s Diary of a Bad Year after class, and I was explaining to him what I’d found so strange about the novel. What is most immediately striking is the form it takes: Coetzee splits each page, first into two, then into three. The top section houses the draft manuscript for the book of “strong opinions” our aging protagonist JC has been asked to write, separated out into chapters with titles like “On terrorism,” “On paedophilia” and “On the origins of the state”; the bottom stores a firsthand account of his life. Later on, when JC meets his beautiful young typist, Anya, the page splits into three, and her perspective settles into this last section on the page. What is also striking is the narrator, an aging South African novelist who wrote Waiting for the Barbarians, then moved to Australia and, importantly, is not J.M. Coetzee. JC on the page versus JC in the flesh; JC versus Coetzee—something about this kept catching at me, but I didn’t quite have the words to explain why. Laughing at my wild gesturing, my teacher hustled me out the door to prepare for his next class but not before sliding me a copy of the summer 2008 issue of Raritan, tapping Jonathan Lear’s name on the cover.

In his review-essay in that issue, “The Ethical Thought of J.M. Coetzee,” Lear, a philosopher and psychoanalyst at the University of Chicago, performs the miraculous work of good reading. The split pages and Coetzee’s doubling, he explains, work to provoke “genuine” ethical thought, rather than the “ersatz” stuff churned out by so many self-styled intellectuals, by inducing in us a “metaphysical ache.” Diary of a Bad Year introduces us to this ache when JC first sees Anya walk by in a “tomato-red shift … startling in its brevity.” The scene arouses in JC the “living recognition,” in Lear’s words, “that in his erotic longing … he is a creature who will soon not be.” But this “ache that is the reality of his demise” is also an ache “for reality.” Stepping back, Lear situates the book in a Western philosophical tradition of intratextual dialogues, but unlike Plato or Kierkegaard, he notes, Coetzee never steps out from behind JC to tell us what he really means to say. The split pages distinguish the author JC and the person JC, the heft of his writing looming over the quotidian humiliations to which he is subject; the official, “moral stances” of his manuscript looking down their noses at his—and later, Anya’s—day-to-day musings, “the stuff of human life.” “This imaginary embedding,” Lear writes, “draw[s] along parts of the reader’s soul that would not be led by argument alone.”

As a young reader, the crucial work of Lear’s essay was to elicit in me a metaphysical ache in two distinct stages: first by implicating me, then by initiating me. He devotes the second half of the review to a brilliant reading of JC’s scandalous accusation that to be American is to be “entangled in a … modern, secular version of blood guilt”: each American is necessarily shamed by being the citizen of a nation that “engages in torture.” That we “can reason [our] way out of the shame—after all, [we] did nothing to deserve it—does not mean that it is not [ours]”; reason, in fact, lays the foundation of “a motivated structure of not-seeing” that wards off shame and numbs the metaphysical ache. In a few pages, Lear had laid out in precise terms the stakes of an inchoate internal struggle that I hadn’t even realized was happening. What does it mean to be the citizen of a country that commits unspeakable acts in your name, a country that you had not chosen to be a part of, run by an administration you did not elect? How have you avoided looking at this? And, crucially, in the face of this dishonor, how do you—not the law, not liberal intellectuals, not your favorite novelist—determine what to do?

For all its philosophical and ethical incisiveness, though, Lear’s piece carried, at the time, more symbolic weight than intellectual, by which I mean I was more attached to what the writing seemed to promise than the words themselves: complete command of his subject material, the writers he invoked and the long literary, cultural and historical lineage to which they all belonged. Without knowing the tradition in which he worked or what it had taken to reach where he was, I had the overwhelming sense that I wanted to do what he had done in that essay.

The flame could’ve easily sputtered out if not for another serendipitous opening. Every Saturday afternoon for much of high school, I’d spend hours in a fluorescent conference room in Rutgers’ Life Sciences Building fiddling around in Excel, trying in vain to help a professor locate the genes that contributed to alcoholism. When the weather permitted, I’d leave to make the forty-minute walk across the Raritan River, along which Rutgers stands, to the library, where I’d try to distract myself until I could leave. Mostly, I spent that time beating linear transformations and surface integrals into my head, but after I learned about Raritan, I began taking my study breaks in the periodicals section, browsing old copies of the magazine.

It was there that I started to nurse what one might call a literary counterlife. Flipping through old issues of Raritan did not supply me with anything as systematic as an education, but given the little regard my family had for reading—I don’t think I’ve ever talked about a single book with them—and the fact that, at school, I had never heard the word “literature” uttered without the one-two punch of “AP” before it, the publication served as a window through which I could see everything I didn’t know, but about which I could learn.

In Raritan I found a kind of tableau: Frank Kermode, Eve Kosofsky Sedgewick, Adam Phillips, Leo Bersani, Joyce Carol Oates, Rosalind Krauss, Christopher Hitchens, Dan Chiasson, James Longenbach, Louis Menand, Ben Sonnenberg, Edward Said. The magazine also introduced me to some of the first poets I ever took seriously during those years when I thought poetry superfluous, most notably John Ashbery, Robert Frost and Frederick Seidel, whose mannered savagery found a home in Raritan as early as 1982. Before reading Raritan, I hadn’t even known that the category of intellectuals existed. The good life my upbringing had laid out for me was something like this: hustle your way into a T-20 for business or computer science, work up to a middle-management position in Jersey, die. Raritan showed there was a path out.

●

Alongside the nearly seventy novels and collections of essays, short stories, poetry and nonfiction he wrote over his lifetime—“Honestly,” Philip Roth groused, “do we have to read every fucking word the guy writes?”—John Updike can also count himself responsible, however indirectly, for Raritan’s creation. The editors were not particularly fond of Updike. Richard Poirier and Thomas R. Edwards, both literary critics and professors of literature at Rutgers, leveled coolly disdainful gazes at him in their 1978 proposal for the magazine:

The publication of a new book by John Updike, let us say, is probably not an event of the same magnitude as the publication of a new book by Bellow or Pynchon, by Elizabeth Bishop or Doris Lessing … He seems at the moment to be a writer of comparatively, and predictably, lesser weight, and for whatever reasons he does not call into play the cultural forces and special interests that are at work on behalf (or against) these other writers.

It was their mutual confusion regarding Updike’s popularity that also solidified matters between Poirier and his successor, Rutgers historian Jackson Lears. One of the questions he had hoped to address when he founded the magazine, Poirier told Lears, was: How does a writer like John Updike get lionized and celebrated as if he’s some genius man of letters? Raritan, in other words, was interested in “cultural power,” as Poirier declared in his prefatory editor’s note: “those intricate movements by which ideas or events, canons or hierarchies of preference, minorities or cultural strata come into existence.” Updike, not considered “a sufficiently rewarding clue to something more important than the texts he writes,” was given no notice in its pages.

His notoriety—to the editors, baffling—was not the sole occasion for the publication. Poirier had also edited and consulted for the Partisan Review from 1963 to 1978, during which the magazine had been housed and fed at Rutgers. By 1978, when William Phillips, co-founder of the Partisan Review, decided to move himself and the operation to Boston University, the mid-century intellectual tradition was all but pushing up daisies: PR was breathing its last gasp, and Phillips had been accelerating rightward for the last decade. With PR’s senescence, Poirier saw an opportunity to create something in its image but sharper, more contemporary, more local. After enough drinks at the Rutgers Club with then-Rutgers president Edward Bloustein, Raritan was born.

Though Raritan, like so many of the other little magazines of the last few decades, took as its model those twentieth-century antecedents—the Dial, the Little Review and especially the Partisan Review—it rested less under the shadows of their historical particulars (the Great Depression and World War II, European modernism and American anti-Stalinism). It was, as critic Robyn Creswell wrote, the “intellectual bridge, or missing link, between those heroic organs of the past … and contemporary little magazines.” Poirier, and later Lears, were more influenced by the ’68 protests, the anti-war movement of the Seventies and the Cold War decades. They sought to mount a rigorous intellectual opposition to the creeping progress of a technocratic, professionalizing world. And unlike PR and its determined anti-nativism, Raritan insisted on being an American magazine. No Europhilia, no craning their necks to catch glimpses across the pond. “The now wearisome perpetual crusade of intellectual Paris … just has no relevance to, or in, our perpetually Emersonian America,” Harold Bloom ruled stentorianly in the first issue (though it must be said that Raritan printed their fair share of mid-century Frenchies, particularly in the early years). Poirier and Lears, after all, were Americanists. Both were wedded to that homegrown intellectual tradition, pragmatism, and had walked down the aisle on two legs: Ralph Waldo Emerson and William James. (Lears in particular considered Frost as much of a pragmatist as the other two, and so as his tenure continued, two legs became three.) The magazine was also supposed to be less disciplined by any particular political doctrine: though it never shied away from politics, it also never tried to be an avant-garde, politically radical enfant terrible. After all, the base of operations wasn’t in New York City, but at a state flagship in New Jersey—that “mythic Nowheresville in urban smart talk for generations,” as Lucy Sante detailed dryly, where reading the issues meandered along at the same leisurely pace as the Raritan River, on whose banks I read them.

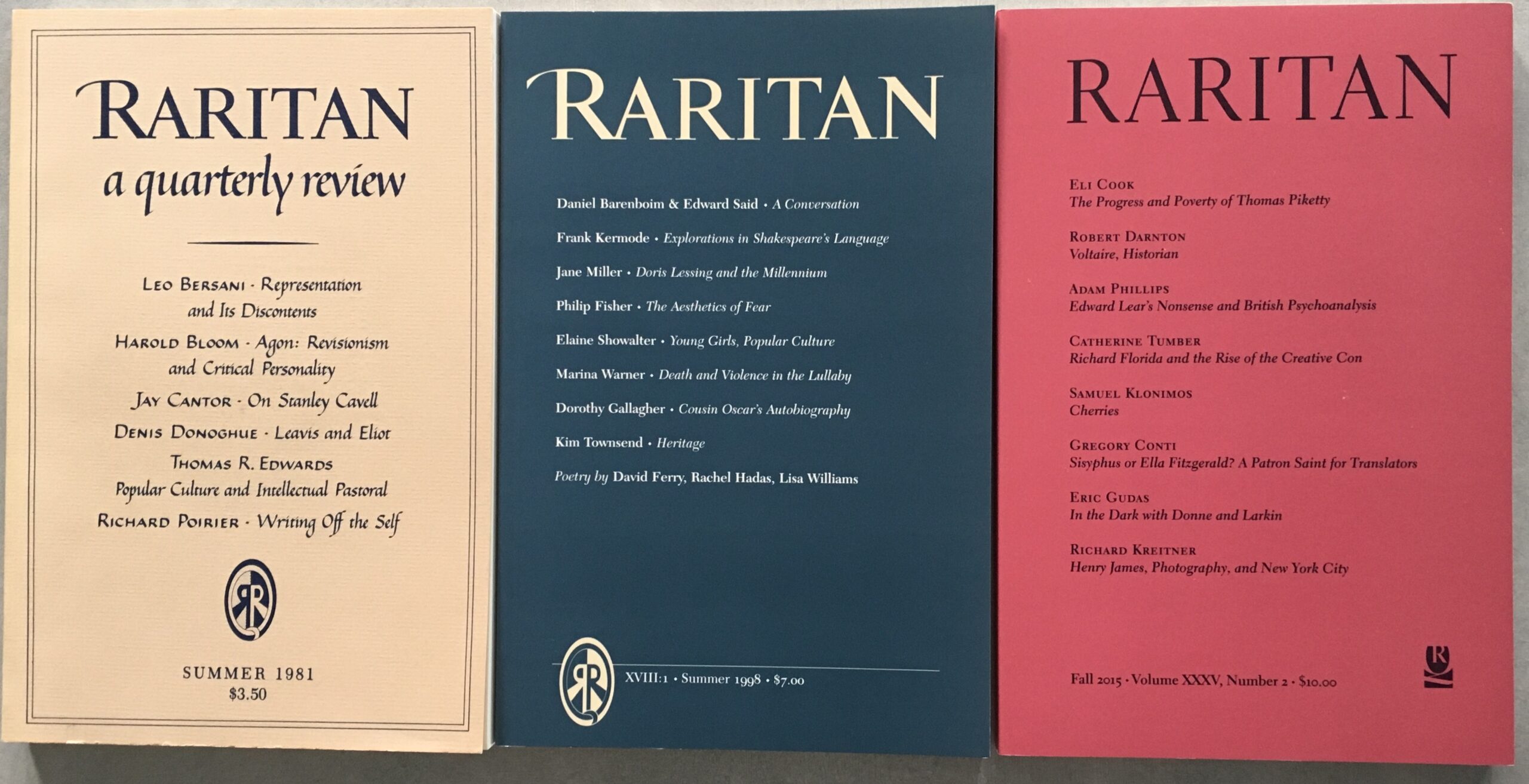

The inaugural issue, published in the summer of 1981, is a little dense under the weight of its bylines: Leo Bersani on mimetic sexuality and violence, Harold Bloom on agon, Jay Cantor on Stanley Cavell’s skepticism, Denis Donoghue on F. R. Leavis’s reading of Eliot and pieces from the editors—Edwards on popular culture and Poirier on self-eradication in literature. The pieces are not particularly easy to swallow; on my initial read, I was uninterested in finishing most of them. But there are three I can still recall to this day.

The first is Edwards’s “High Minds, Low Thoughts,” an interrogation of the fraught relationship between intellectuals and “popular culture,” which had begun to get “interesting” for “high-minded people.” His piece typified an enduring approach Raritan would take to culture, one that split from Partisan Review during its heyday. The point was not to condemn mass culture or the powers that produced it; rather, the editors and their writers aimed to take the popular object on its own terms—to approach it “without seeming to fear that doing so will compromise their intelligence or damage their ability to be serious about other things”—and to understand and narrate the process by which certain subjects and perspectives were legitimated while others were rendered marginal.

If I remember Edwards’s essay for its clarity of argument and prose, Bloom’s “Agon: Revisionism and Critical Personality” lingers for precisely the opposite reasons. It was the first thing, in conscious memory at least, I’d ever fought so hard to read. His references were so dizzyingly exhaustive, his prose as “outrageous” as he recommends the “language of American criticism” be, that reading him felt not unlike being slowly, steadily waterboarded. A lifetime’s worth of authors, hyphenated neologisms and eponymous adjectives populates the pages: Hazlitt, Burke, Arnold (many exist only as floating last names); language-as-demiurge, ephebe-poet, masturbation-rape; Emersonian, Coleridgean, Stevensian. The essay, as the title suggests, is yet another continuation of Bloom’s theory of poetic anxiety and influence: successors struggle against the presence of their predecessors in their work, and struggle to usurp what it was that had originally drawn them to their predecessors. A screed against deconstruction and its belief that language is somehow a thing unto itself, it was also insistent on a pragmatist American criticism that affirmed “the self over language.” Bloom was the first to sketch for me an image of a distinctly American literary canon, poetry and philosophy, much of which, in his view, was indebted to the pragmatic method of asking the text, “what is it good for, what can I do with it, what can it do for me, what can I make it mean?”

In stark contrast with the sentimental humanism leaking from Bloom’s piece, Poirier’s “Writing Off the Self” broached frankly the phenomenon of self-eradication in Western literature. Why, he asked, does there exist this perennial desire, from Dante to Foucault, to “eradicate the human self”? (Emerson longed to “see the universe unpeopled and himself invisible.” “My entire delight was in observing without being myself noticed,” wrote John Ruskin.) How and why is criticism, with its attachments to humanism and the human presence, ill-equipped to recognize the pleasure one might derive from “looking on a landscape from which the human presence has been banished”? What allowances are we then granted when we encounter these moments of dissolution as steps not toward redemption or resurrection, as they are in the Christian mode of self-eradication (Milton, Eliot, Spenser), but approaching something entirely non-human? Put differently, what does being a “transparent eyeball” do for Emerson?

For all the difficulty reading it presented at the time, Raritan was the first place I found the kind of muscular writing and thought that could, as Poirier once put it, “create capacities.” With this training, the fantasy was, one could learn to detect those moments of quickening when things seem to fairly hum with vitality, interrupting the otherwise interminable flatness of experience. Only with this awareness of “how much of life ha[s] dribbled through one’s fingers” could I escape what composition professor William E. Coles called “Themewriting”—abstract, bloodless clichés that gestured limply toward some vague thing in the distance—to become “alive inside sentences.” I heard the message loud and clear: this “struggle for verbal consciousness,” as D.H. Lawrence put it, was how I could preserve my life.

Yet even as I came to stake my life on it, language’s shortcomings also tormented me. Though its stated purpose was to explore the mechanisms of cultural power, it was Raritan’s writing on American poetry, which foregrounded the clash between voice, language and the self, that left its most enduring mark. Take Whitman in “As I Ebb’d with the Ocean of Life,” which Bloom raises in “Agon”: “amid all that blab whose echoes recoil upon / me I have not once had the least idea who or what I am, / But that before all my arrogant poems the real Me stands yet / untouch’d, untold, altogether unreach’d.” Whatever “arrogant” voices in his poetry, “all that blab” reverberating in his head, some crucial gulf still yawns between the self the “blab” intimates—a tentative construction—and the “untouch’d, untold, altogether unreach’d” self—“the real Me”—which neither language nor sentence sounds can meet. “The voices heard in Anglo-American literature,” Poirier wrote, “are never allowed even to pretend that they master the materials, the language, on which their very claim to existence depends.” That language is unstable, that the self is not fixed—these are old chestnuts, perhaps, but Raritan’s great accomplishment was to revitalize them and to re-present them to me as matters of urgent, existential import.

Far from always moving me to talk or write about the work in its pages, then, reading Raritan often made me want to stop. The intellectual and aesthetic experience was so totalizing it struck me dumb. For days at a time in high school, overwhelmed by my convictions of, at once, the primacy and the impossibility of language, I would avoid my family, stare past teachers, skip lunch with friends to sit alone in the courtyard, convinced that, while my physical body was stuck in New Jersey, the “altogether unreach’d” self with whom I communed floated somewhere hundreds of miles away, suspended in a gelatinous float tank of tiny letters. No one around me read the same things, so no one else lived in the same world. Besides, I had no way of articulating why these texts felt so true or why certain sentences felt so right; they just were. To put words to these feelings, I thought, I’d have to become like the writers I read, but the chasm between us seemed impassable.

●

It would be easy to say here that reading Raritan oriented me tropically toward a life in letters or some tony intellectual world, but it didn’t. I enrolled in college as a biostatistics major and spent most of my tenure there coding in SAS and failing probability exams. Raritan left me with something closer to an understanding than an expectation: that reading, writing and our love of the two, when done well, are hard work and cost us something, and that language can, and will, betray us. Nevertheless, we continue. Poirier puts it well in a reflection on being a student at Amherst and a teacher at Harvard:

Reading can be a civilizing process, not because the meanings it gathers may be good for us—they may in fact sometimes be quite pernicious—but because that most demanding form of writing and reading called literature often asks us to acknowledge, in the twists and turns of its language, the presence of ancestral kin who cared deeply about what words were doing to them and what they might do in return. … Good reading and good writing are, first and last, lots of work.

The kind of pleasure that mattered, or so Raritan taught me, didn’t come from relaxation. It came from agitation, exertion, working until you “discover the strains, tensions, and exaltations that give birth to things.”

After I graduated from high school, nearly five years would pass before I picked up another issue of Raritan. In part, it became harder to access issues—at most, one piece per issue is digitally available; often, none are. Besides, I didn’t really mind. I’d found sexier fish to fry—big tomes of jargon and genealogy, and slim, neat issues of nose-thumbing and eye-rolling that urged me to break with tradition, fight the power, take down the man. Living an active life within the larger community began to feel more enticing than the pure contemplation I’d associated with Raritan. By the end of college, I had all but forgotten about old faithful. I graduated, moved to the city, and began my series of paid (and unpaid) magazine internships. Waiting in the office of a professor whose panel I’d just attended, I was absentmindedly scanning his bookshelves when a copy of Raritan caught my eye. This was the first time since leaving for college I’d encountered a physical copy of the publication. Searching it up later, I learned Raritan was soon to close its doors.

In his penultimate editor’s note last winter, Lears announced that, due to “inadequate funding” from the Rutgers administration, Raritan would have to cease operations. “Better to shut the magazine down,” he wrote, “than to accept a prescription for chaos and mediocrity.” The university austerity portion of this story is too familiar at this point: at Rutgers, particularly after 2008, Raritan found itself having to justify year after year everything from the funding of its staff to the paper on which it was printed. University leadership soured, support became grudging, and administrators presented new gripes, chief among them that the magazine wasn’t doing enough to facilitate “synergy” with the institutions and communities within Rutgers. With Lears set to retire at the end of the 2025 school year, the situation, it seems, became untenable.

Rutgers certainly contributed to the magazine’s closing, but it is too easy to blame just the university. Raritan in its later years, if ever, was not the kind of publication that sought to appeal to younger readers or, for that matter, readers who didn’t already know it existed. Its cultural footprint has surely been shrinking, its circulation waning, amid paltry efforts to expand its readership. Outside of that professor’s office, I can’t remember the last time I saw its name anywhere. When I told friends that I was writing a tribute to the publication, the overwhelming majority, even the well-read literary types, had never heard of it. The few who had knew little else besides its name.

Casting a wide net returns many reasons. For one, Raritan has resisted adaptation to the internet even more than Harper’s, possibly the magazine most outwardly hostile to the digital world that I know. The aversion to the internet that both magazines share arises from similar sensibilities, including a refusal to capitulate to the structures and incentives of big tech and the apprehension of the magazine as first and foremost a beautiful, tactile object. I am sympathetic to these sensibilities—it is hard to want to do serious intellectual work and not feel compelled by the “move always toward a deepening obscurity,” in Philip Connors’s words—but Raritan appeared to give up altogether the opportunity to court readers, particularly the younger ones. The publication has only the faintest whisper of an online presence, the contents of its pieces cannot be digitally searched, and its website, which looks more like the home of a neglected environmental-science institute than the quiet heavyweight it once was, stores almost no publicly accessible archives. While writing this piece, I had to call in nearly a dozen favors to get my hands on old copies. Not a single piece or issue from the Eighties—their best decade, the one that first seduced me—is available online; the only proof of their existence are the rare physical copies, the bylines on the Raritan site that lead nowhere and the dusty off-site archives of university libraries.

Another reason so few readers know about the magazine may be because Raritan operated in those brackish waters between the university and the public, targeting that unicorn-like figure of the educated general reader who wishes to think a little harder than they typically do. Though Poirier strove to distance Raritan from the university by, for instance, instituting iron-fisted embargoes on footnotes and disciplinary jargon, the magazine always read like a refuge or an outpost for academics. Yet this institutional proximity doesn’t quite account for its marginality. While the intellectual publications of its era like, say, Salmagundi, languish in similar obscurity, other, more recent ones like n+1, which stomp on similar extra- and para-academic grounds, boast much higher circulation and cultural relevance. As its contributors (and readership) aged, Raritan failed to engage in the same kind of acute, self-conscious self-questioning as these newer little magazines, even as the conditions around it shifted radically: adjunctification; the hollowing out of tenure and faculty governance; plummeting funding; world-historical changes in how people consume information; the gradual erosion of the economic, social and cultural foundations of public intellectual work; and the fact, not to be ignored, that many of its main writers were quickly approaching or even more quickly departing septuagenarian status. Why was this? Why had Raritan not propagated a younger generation of writers who wanted to write for them? Was it their fault? And will it matter, particularly for this younger generation that hasn’t heard of them, that they’re gone?

In Diary of a Bad Year, JC considers the distance between the “thudding, mechanical music favoured by the young” and the nineteenth-century art-song. His response to those who “querulously demand to know” why music cannot simply continue in the nineteenth-century symphonic tradition is blunt: “The animating principles of that music are dead and cannot be revived.” Anything that tried to would immediately sound anachronistic. Likewise, the principles that animated Raritan and its vision of intellectual life could not be sustained in the present moment and will not be revived in the foreseeable future. Money no longer exists for para-academic institutions, post-GI Bill largesse has long since disappeared, and the once general sense, “now weirdly archaic,” as Kermode recounted, “that literary criticism was extremely important, possibly the most important humanistic discipline, not only in the universities but also in the civilized world more generally,” has not so much faded as been chased out of town. Raritan’s shuttering, the deaths of so many of its contributors—including Jonathan Lear, who passed away suddenly and devastatingly as I was writing this—and the rapid aging of the rest of them, are confirmations of that thing we know now very well: an entire era of literary culture is at its end.

As the great oaks of this older culture have fallen, no one has quite grown tall enough to replace them, even amid the flourishing of the more recent little magazines. It’s hard to think of someone now who speaks, or at least intends to, with as much critical authority to a large general public as Harold Bloom, Frank Kermode or Edward Said once did. That the romantic geniuses, prophets and demiurges I met on my first forays all seemed to slowly fade from Raritan’s pages is no doubt because age has helped shed some of the scales from my eyes, but it is also a direct consequence of how the function of the humanities and the university has changed. Far from a liberal education whose ambition, as W.E.B. Du Bois trumpeted, is “delving for Truth, and searching out the hidden beauties of life, and learning the good of living,” contemporary institutions appear interested in solely vocational justifications for the humanities, hence the mass specialization, the single-minded focus on what we might disdainfully call “research outputs.” How could anyone today write the way Kermode did, with such singular, encyclopedic authority on everything from apocalyptic thought to Shakespeare to the Bible as literature, addressed to seemingly everyone from the mythic common reader to the highest reaches of the ivory towers?

And yet, as I grew older and began thinking about what it meant to take intellectual inquiry seriously in these times of economic precarity, cultural impotence and the incessant feeling of belatedness, I didn’t turn to Raritan, whose missives about living a life of the mind looked sepia-toned, straight from the Eighties. Instead, I turned to pieces like n+1’s “Cultural Revolution,” or the Baffler’s “What Are Intellectuals Good For?,” which addressed premises that Raritan was perhaps too old to confront head-on: that it is too late for literary criticism, too late for writing, and every publication and intellectual institution you know is either closing shop or being sold for parts. In other words, the future is foreclosed; what, then, is to be done?

●

Whenever a little magazine dies, a sea of obituaries and requiems seems to flood forth with desultory pronouncements about the state of literature, the reading public, the contemporary writers that always fall short of their predecessors. As n+1 co-founder Mark Greif put it in a Partisan Review retrospective, the moribund little magazine is always described as some crucial organ of mediation between haute intellectualism and the curious general public, whose death portends some looming crisis. The magazine is made to stand in for “the phantom flagship of ‘what we have lost.’” In these times when it seems so needed—other magazines are selling out, everything is speeding up, and the young people (God, are they even reading anymore?) are only getting stupider—we feel its absence grievously.

In response to the perennial question of the reading public, Poirier offered his own answer. In an editor’s note from 1982, entitled “Reading Anyone? Or, Is There a Reading Public?,” he strides through the popular attitudes of the day: books aren’t selling, education has been reduced to “gladiatorial training,” and a reading public able to rise to the occasion of an earlier public no longer exists, except, perhaps, in the academic community. (Sound familiar?) This, Poirier tells us, is not interesting. What is more compelling is the idea that a reading public can be produced; that, rather than expecting that public to demonstrate “a spontaneous interest in high culture,” more rarefied readers ought to remember that “people first need to know that they are endowed with cultural treasures before they can be expected to care about them.” (Thus Poirier’s decision to co-found the publisher Library of America, a Herculean effort to remind North American readers of their literary inheritance by collecting and publishing what might have otherwise scattered to the winds.) Performing—in other words, demonstrating—the work of reading, writing and knowing was, he felt, the only way to teach it, or to teach people to aspire to it.

As Greif concluded, a good magazine’s great accomplishment is that it directs its gaze “just slightly over the head[s]” of its readers, impelling them to go “up on tiptoe,” hoping to reach the heights that the writers themselves attain when they have truly risen to the occasion. At its best, when the various fantasy systems—those of the writers, the readers, the funders, even representatives of the “real world” of politics, business and government—could hammer out a deal, this collective conceit produced “an aspirational estimation of ‘the public.’” Aspirational here, Grief explains, doesn’t mean something moral like nobility or, worse, the pernicious commercial form appended to market-research words like “lifestyle”; rather, it refers to the sense that you can be better than you are. A good magazine constructs frameworks for understanding and clarifying the world, yes, but arguably its most crucial function is to initiate the reader, to give them a sense of how they could be. The root of my young attachment to Raritan was the great metaphysical ache I felt when encountering those pieces. Reading Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s “Epistemology of the Closet,” Adam Phillips’s “The Truth of Psychoanalysis” or James Longenbach’s “Disjunction in Poetry” felt like running after a bus, watching the distance between us grow and grow. All the same, it made me want to try.

There are a thousand and one ways to numb yourself to life, how you feel and what you say, each more effective than the last. To willingly grapple with language and the self, the kind of struggle I witnessed on the pages of Raritan and in myself while reading them, is hard work; harder yet is to convince other people of its necessity. But through that magazine, I began to see the glimmers of the edges of what real thinking could look like, thinking that was an activity, a battle, in which one confronted the limits of life, history and language itself. Raritan taught me to meet language—not just to scan but to read aloud the words on the page, let them linger, savor them—and then to listen for the agitation in myself, the pulse that would kick and quicken and, at times, drive me to my feet with the force of its exertion. Where was the pleasure? I learned to ask myself. Where was the pain? What forms of the self and what structures of the imagination did these words throw into sharp relief? When, how and why did my language betray me?

Attention to these confrontations had the curious effect of both contracting and dilating time. I became aware of how precarious and fleeting these moments were, how quickly these states seemed to take and leave me, and yet—at least I could watch it happen. Since discovering Raritan all those years ago, other magazines and writers have joined its ranks, and the range of models I have for good writing and good thinking has grown wide and promiscuous. Still, the journal’s folding closes the book on the first intellectual—and historical—tradition to which I ever wanted to belong.

Most of all, I will miss how Raritan made the non-urgent feel urgent, not by pegging its writing to current events or the shifting tides of discourse, but because good thinking exudes its own kind of clarion call for us to do the same—to listen, to look, to do as Rilke says and change our lives. I echo here the closing sentence of Randall Jarrell’s “Poets, Critics and Readers”: Read at whim! read at whim!

Image credit: Photos courtesy of Jackson Lears and Stephanie Volmer

Raritan—the all-American literary quarterly of a pre-internet world—closed its doors last spring, ending a nearly half-century run of literature, politics, art and cultural criticism. It passed with a soft sigh, a sound almost inaudible unless you’d been listening for it. Truth be told, when I heard that Raritan was shuttering, I was surprised it was still around at all.

I learned to read, as it were, from Raritan. I first encountered it the way many young readers come to early polestars—through a high school English teacher. We had been discussing J. M. Coetzee’s Diary of a Bad Year after class, and I was explaining to him what I’d found so strange about the novel. What is most immediately striking is the form it takes: Coetzee splits each page, first into two, then into three. The top section houses the draft manuscript for the book of “strong opinions” our aging protagonist JC has been asked to write, separated out into chapters with titles like “On terrorism,” “On paedophilia” and “On the origins of the state”; the bottom stores a firsthand account of his life. Later on, when JC meets his beautiful young typist, Anya, the page splits into three, and her perspective settles into this last section on the page. What is also striking is the narrator, an aging South African novelist who wrote Waiting for the Barbarians, then moved to Australia and, importantly, is not J.M. Coetzee. JC on the page versus JC in the flesh; JC versus Coetzee—something about this kept catching at me, but I didn’t quite have the words to explain why. Laughing at my wild gesturing, my teacher hustled me out the door to prepare for his next class but not before sliding me a copy of the summer 2008 issue of Raritan, tapping Jonathan Lear’s name on the cover.

In his review-essay in that issue, “The Ethical Thought of J.M. Coetzee,” Lear, a philosopher and psychoanalyst at the University of Chicago, performs the miraculous work of good reading. The split pages and Coetzee’s doubling, he explains, work to provoke “genuine” ethical thought, rather than the “ersatz” stuff churned out by so many self-styled intellectuals, by inducing in us a “metaphysical ache.” Diary of a Bad Year introduces us to this ache when JC first sees Anya walk by in a “tomato-red shift … startling in its brevity.” The scene arouses in JC the “living recognition,” in Lear’s words, “that in his erotic longing … he is a creature who will soon not be.” But this “ache that is the reality of his demise” is also an ache “for reality.” Stepping back, Lear situates the book in a Western philosophical tradition of intratextual dialogues, but unlike Plato or Kierkegaard, he notes, Coetzee never steps out from behind JC to tell us what he really means to say. The split pages distinguish the author JC and the person JC, the heft of his writing looming over the quotidian humiliations to which he is subject; the official, “moral stances” of his manuscript looking down their noses at his—and later, Anya’s—day-to-day musings, “the stuff of human life.” “This imaginary embedding,” Lear writes, “draw[s] along parts of the reader’s soul that would not be led by argument alone.”

As a young reader, the crucial work of Lear’s essay was to elicit in me a metaphysical ache in two distinct stages: first by implicating me, then by initiating me. He devotes the second half of the review to a brilliant reading of JC’s scandalous accusation that to be American is to be “entangled in a … modern, secular version of blood guilt”: each American is necessarily shamed by being the citizen of a nation that “engages in torture.” That we “can reason [our] way out of the shame—after all, [we] did nothing to deserve it—does not mean that it is not [ours]”; reason, in fact, lays the foundation of “a motivated structure of not-seeing” that wards off shame and numbs the metaphysical ache. In a few pages, Lear had laid out in precise terms the stakes of an inchoate internal struggle that I hadn’t even realized was happening. What does it mean to be the citizen of a country that commits unspeakable acts in your name, a country that you had not chosen to be a part of, run by an administration you did not elect? How have you avoided looking at this? And, crucially, in the face of this dishonor, how do you—not the law, not liberal intellectuals, not your favorite novelist—determine what to do?

For all its philosophical and ethical incisiveness, though, Lear’s piece carried, at the time, more symbolic weight than intellectual, by which I mean I was more attached to what the writing seemed to promise than the words themselves: complete command of his subject material, the writers he invoked and the long literary, cultural and historical lineage to which they all belonged. Without knowing the tradition in which he worked or what it had taken to reach where he was, I had the overwhelming sense that I wanted to do what he had done in that essay.

The flame could’ve easily sputtered out if not for another serendipitous opening. Every Saturday afternoon for much of high school, I’d spend hours in a fluorescent conference room in Rutgers’ Life Sciences Building fiddling around in Excel, trying in vain to help a professor locate the genes that contributed to alcoholism. When the weather permitted, I’d leave to make the forty-minute walk across the Raritan River, along which Rutgers stands, to the library, where I’d try to distract myself until I could leave. Mostly, I spent that time beating linear transformations and surface integrals into my head, but after I learned about Raritan, I began taking my study breaks in the periodicals section, browsing old copies of the magazine.

It was there that I started to nurse what one might call a literary counterlife. Flipping through old issues of Raritan did not supply me with anything as systematic as an education, but given the little regard my family had for reading—I don’t think I’ve ever talked about a single book with them—and the fact that, at school, I had never heard the word “literature” uttered without the one-two punch of “AP” before it, the publication served as a window through which I could see everything I didn’t know, but about which I could learn.

In Raritan I found a kind of tableau: Frank Kermode, Eve Kosofsky Sedgewick, Adam Phillips, Leo Bersani, Joyce Carol Oates, Rosalind Krauss, Christopher Hitchens, Dan Chiasson, James Longenbach, Louis Menand, Ben Sonnenberg, Edward Said. The magazine also introduced me to some of the first poets I ever took seriously during those years when I thought poetry superfluous, most notably John Ashbery, Robert Frost and Frederick Seidel, whose mannered savagery found a home in Raritan as early as 1982. Before reading Raritan, I hadn’t even known that the category of intellectuals existed. The good life my upbringing had laid out for me was something like this: hustle your way into a T-20 for business or computer science, work up to a middle-management position in Jersey, die. Raritan showed there was a path out.

●

Alongside the nearly seventy novels and collections of essays, short stories, poetry and nonfiction he wrote over his lifetime—“Honestly,” Philip Roth groused, “do we have to read every fucking word the guy writes?”—John Updike can also count himself responsible, however indirectly, for Raritan’s creation. The editors were not particularly fond of Updike. Richard Poirier and Thomas R. Edwards, both literary critics and professors of literature at Rutgers, leveled coolly disdainful gazes at him in their 1978 proposal for the magazine:

It was their mutual confusion regarding Updike’s popularity that also solidified matters between Poirier and his successor, Rutgers historian Jackson Lears. One of the questions he had hoped to address when he founded the magazine, Poirier told Lears, was: How does a writer like John Updike get lionized and celebrated as if he’s some genius man of letters? Raritan, in other words, was interested in “cultural power,” as Poirier declared in his prefatory editor’s note: “those intricate movements by which ideas or events, canons or hierarchies of preference, minorities or cultural strata come into existence.” Updike, not considered “a sufficiently rewarding clue to something more important than the texts he writes,” was given no notice in its pages.

His notoriety—to the editors, baffling—was not the sole occasion for the publication. Poirier had also edited and consulted for the Partisan Review from 1963 to 1978, during which the magazine had been housed and fed at Rutgers. By 1978, when William Phillips, co-founder of the Partisan Review, decided to move himself and the operation to Boston University, the mid-century intellectual tradition was all but pushing up daisies: PR was breathing its last gasp, and Phillips had been accelerating rightward for the last decade. With PR’s senescence, Poirier saw an opportunity to create something in its image but sharper, more contemporary, more local. After enough drinks at the Rutgers Club with then-Rutgers president Edward Bloustein, Raritan was born.

Though Raritan, like so many of the other little magazines of the last few decades, took as its model those twentieth-century antecedents—the Dial, the Little Review and especially the Partisan Review—it rested less under the shadows of their historical particulars (the Great Depression and World War II, European modernism and American anti-Stalinism). It was, as critic Robyn Creswell wrote, the “intellectual bridge, or missing link, between those heroic organs of the past … and contemporary little magazines.” Poirier, and later Lears, were more influenced by the ’68 protests, the anti-war movement of the Seventies and the Cold War decades. They sought to mount a rigorous intellectual opposition to the creeping progress of a technocratic, professionalizing world. And unlike PR and its determined anti-nativism, Raritan insisted on being an American magazine. No Europhilia, no craning their necks to catch glimpses across the pond. “The now wearisome perpetual crusade of intellectual Paris … just has no relevance to, or in, our perpetually Emersonian America,” Harold Bloom ruled stentorianly in the first issue (though it must be said that Raritan printed their fair share of mid-century Frenchies, particularly in the early years). Poirier and Lears, after all, were Americanists. Both were wedded to that homegrown intellectual tradition, pragmatism, and had walked down the aisle on two legs: Ralph Waldo Emerson and William James. (Lears in particular considered Frost as much of a pragmatist as the other two, and so as his tenure continued, two legs became three.) The magazine was also supposed to be less disciplined by any particular political doctrine: though it never shied away from politics, it also never tried to be an avant-garde, politically radical enfant terrible. After all, the base of operations wasn’t in New York City, but at a state flagship in New Jersey—that “mythic Nowheresville in urban smart talk for generations,” as Lucy Sante detailed dryly, where reading the issues meandered along at the same leisurely pace as the Raritan River, on whose banks I read them.

The inaugural issue, published in the summer of 1981, is a little dense under the weight of its bylines: Leo Bersani on mimetic sexuality and violence, Harold Bloom on agon, Jay Cantor on Stanley Cavell’s skepticism, Denis Donoghue on F. R. Leavis’s reading of Eliot and pieces from the editors—Edwards on popular culture and Poirier on self-eradication in literature. The pieces are not particularly easy to swallow; on my initial read, I was uninterested in finishing most of them. But there are three I can still recall to this day.

The first is Edwards’s “High Minds, Low Thoughts,” an interrogation of the fraught relationship between intellectuals and “popular culture,” which had begun to get “interesting” for “high-minded people.” His piece typified an enduring approach Raritan would take to culture, one that split from Partisan Review during its heyday. The point was not to condemn mass culture or the powers that produced it; rather, the editors and their writers aimed to take the popular object on its own terms—to approach it “without seeming to fear that doing so will compromise their intelligence or damage their ability to be serious about other things”—and to understand and narrate the process by which certain subjects and perspectives were legitimated while others were rendered marginal.

If I remember Edwards’s essay for its clarity of argument and prose, Bloom’s “Agon: Revisionism and Critical Personality” lingers for precisely the opposite reasons. It was the first thing, in conscious memory at least, I’d ever fought so hard to read. His references were so dizzyingly exhaustive, his prose as “outrageous” as he recommends the “language of American criticism” be, that reading him felt not unlike being slowly, steadily waterboarded. A lifetime’s worth of authors, hyphenated neologisms and eponymous adjectives populates the pages: Hazlitt, Burke, Arnold (many exist only as floating last names); language-as-demiurge, ephebe-poet, masturbation-rape; Emersonian, Coleridgean, Stevensian. The essay, as the title suggests, is yet another continuation of Bloom’s theory of poetic anxiety and influence: successors struggle against the presence of their predecessors in their work, and struggle to usurp what it was that had originally drawn them to their predecessors. A screed against deconstruction and its belief that language is somehow a thing unto itself, it was also insistent on a pragmatist American criticism that affirmed “the self over language.” Bloom was the first to sketch for me an image of a distinctly American literary canon, poetry and philosophy, much of which, in his view, was indebted to the pragmatic method of asking the text, “what is it good for, what can I do with it, what can it do for me, what can I make it mean?”

In stark contrast with the sentimental humanism leaking from Bloom’s piece, Poirier’s “Writing Off the Self” broached frankly the phenomenon of self-eradication in Western literature. Why, he asked, does there exist this perennial desire, from Dante to Foucault, to “eradicate the human self”? (Emerson longed to “see the universe unpeopled and himself invisible.” “My entire delight was in observing without being myself noticed,” wrote John Ruskin.) How and why is criticism, with its attachments to humanism and the human presence, ill-equipped to recognize the pleasure one might derive from “looking on a landscape from which the human presence has been banished”? What allowances are we then granted when we encounter these moments of dissolution as steps not toward redemption or resurrection, as they are in the Christian mode of self-eradication (Milton, Eliot, Spenser), but approaching something entirely non-human? Put differently, what does being a “transparent eyeball” do for Emerson?

For all the difficulty reading it presented at the time, Raritan was the first place I found the kind of muscular writing and thought that could, as Poirier once put it, “create capacities.” With this training, the fantasy was, one could learn to detect those moments of quickening when things seem to fairly hum with vitality, interrupting the otherwise interminable flatness of experience. Only with this awareness of “how much of life ha[s] dribbled through one’s fingers” could I escape what composition professor William E. Coles called “Themewriting”—abstract, bloodless clichés that gestured limply toward some vague thing in the distance—to become “alive inside sentences.” I heard the message loud and clear: this “struggle for verbal consciousness,” as D.H. Lawrence put it, was how I could preserve my life.

Yet even as I came to stake my life on it, language’s shortcomings also tormented me. Though its stated purpose was to explore the mechanisms of cultural power, it was Raritan’s writing on American poetry, which foregrounded the clash between voice, language and the self, that left its most enduring mark. Take Whitman in “As I Ebb’d with the Ocean of Life,” which Bloom raises in “Agon”: “amid all that blab whose echoes recoil upon / me I have not once had the least idea who or what I am, / But that before all my arrogant poems the real Me stands yet / untouch’d, untold, altogether unreach’d.” Whatever “arrogant” voices in his poetry, “all that blab” reverberating in his head, some crucial gulf still yawns between the self the “blab” intimates—a tentative construction—and the “untouch’d, untold, altogether unreach’d” self—“the real Me”—which neither language nor sentence sounds can meet. “The voices heard in Anglo-American literature,” Poirier wrote, “are never allowed even to pretend that they master the materials, the language, on which their very claim to existence depends.” That language is unstable, that the self is not fixed—these are old chestnuts, perhaps, but Raritan’s great accomplishment was to revitalize them and to re-present them to me as matters of urgent, existential import.

Far from always moving me to talk or write about the work in its pages, then, reading Raritan often made me want to stop. The intellectual and aesthetic experience was so totalizing it struck me dumb. For days at a time in high school, overwhelmed by my convictions of, at once, the primacy and the impossibility of language, I would avoid my family, stare past teachers, skip lunch with friends to sit alone in the courtyard, convinced that, while my physical body was stuck in New Jersey, the “altogether unreach’d” self with whom I communed floated somewhere hundreds of miles away, suspended in a gelatinous float tank of tiny letters. No one around me read the same things, so no one else lived in the same world. Besides, I had no way of articulating why these texts felt so true or why certain sentences felt so right; they just were. To put words to these feelings, I thought, I’d have to become like the writers I read, but the chasm between us seemed impassable.

●

It would be easy to say here that reading Raritan oriented me tropically toward a life in letters or some tony intellectual world, but it didn’t. I enrolled in college as a biostatistics major and spent most of my tenure there coding in SAS and failing probability exams. Raritan left me with something closer to an understanding than an expectation: that reading, writing and our love of the two, when done well, are hard work and cost us something, and that language can, and will, betray us. Nevertheless, we continue. Poirier puts it well in a reflection on being a student at Amherst and a teacher at Harvard:

The kind of pleasure that mattered, or so Raritan taught me, didn’t come from relaxation. It came from agitation, exertion, working until you “discover the strains, tensions, and exaltations that give birth to things.”

After I graduated from high school, nearly five years would pass before I picked up another issue of Raritan. In part, it became harder to access issues—at most, one piece per issue is digitally available; often, none are. Besides, I didn’t really mind. I’d found sexier fish to fry—big tomes of jargon and genealogy, and slim, neat issues of nose-thumbing and eye-rolling that urged me to break with tradition, fight the power, take down the man. Living an active life within the larger community began to feel more enticing than the pure contemplation I’d associated with Raritan. By the end of college, I had all but forgotten about old faithful. I graduated, moved to the city, and began my series of paid (and unpaid) magazine internships. Waiting in the office of a professor whose panel I’d just attended, I was absentmindedly scanning his bookshelves when a copy of Raritan caught my eye. This was the first time since leaving for college I’d encountered a physical copy of the publication. Searching it up later, I learned Raritan was soon to close its doors.

In his penultimate editor’s note last winter, Lears announced that, due to “inadequate funding” from the Rutgers administration, Raritan would have to cease operations. “Better to shut the magazine down,” he wrote, “than to accept a prescription for chaos and mediocrity.” The university austerity portion of this story is too familiar at this point: at Rutgers, particularly after 2008, Raritan found itself having to justify year after year everything from the funding of its staff to the paper on which it was printed. University leadership soured, support became grudging, and administrators presented new gripes, chief among them that the magazine wasn’t doing enough to facilitate “synergy” with the institutions and communities within Rutgers. With Lears set to retire at the end of the 2025 school year, the situation, it seems, became untenable.

Rutgers certainly contributed to the magazine’s closing, but it is too easy to blame just the university. Raritan in its later years, if ever, was not the kind of publication that sought to appeal to younger readers or, for that matter, readers who didn’t already know it existed. Its cultural footprint has surely been shrinking, its circulation waning, amid paltry efforts to expand its readership. Outside of that professor’s office, I can’t remember the last time I saw its name anywhere. When I told friends that I was writing a tribute to the publication, the overwhelming majority, even the well-read literary types, had never heard of it. The few who had knew little else besides its name.

Casting a wide net returns many reasons. For one, Raritan has resisted adaptation to the internet even more than Harper’s, possibly the magazine most outwardly hostile to the digital world that I know. The aversion to the internet that both magazines share arises from similar sensibilities, including a refusal to capitulate to the structures and incentives of big tech and the apprehension of the magazine as first and foremost a beautiful, tactile object. I am sympathetic to these sensibilities—it is hard to want to do serious intellectual work and not feel compelled by the “move always toward a deepening obscurity,” in Philip Connors’s words—but Raritan appeared to give up altogether the opportunity to court readers, particularly the younger ones. The publication has only the faintest whisper of an online presence, the contents of its pieces cannot be digitally searched, and its website, which looks more like the home of a neglected environmental-science institute than the quiet heavyweight it once was, stores almost no publicly accessible archives. While writing this piece, I had to call in nearly a dozen favors to get my hands on old copies. Not a single piece or issue from the Eighties—their best decade, the one that first seduced me—is available online; the only proof of their existence are the rare physical copies, the bylines on the Raritan site that lead nowhere and the dusty off-site archives of university libraries.

Another reason so few readers know about the magazine may be because Raritan operated in those brackish waters between the university and the public, targeting that unicorn-like figure of the educated general reader who wishes to think a little harder than they typically do. Though Poirier strove to distance Raritan from the university by, for instance, instituting iron-fisted embargoes on footnotes and disciplinary jargon, the magazine always read like a refuge or an outpost for academics. Yet this institutional proximity doesn’t quite account for its marginality. While the intellectual publications of its era like, say, Salmagundi, languish in similar obscurity, other, more recent ones like n+1, which stomp on similar extra- and para-academic grounds, boast much higher circulation and cultural relevance. As its contributors (and readership) aged, Raritan failed to engage in the same kind of acute, self-conscious self-questioning as these newer little magazines, even as the conditions around it shifted radically: adjunctification; the hollowing out of tenure and faculty governance; plummeting funding; world-historical changes in how people consume information; the gradual erosion of the economic, social and cultural foundations of public intellectual work; and the fact, not to be ignored, that many of its main writers were quickly approaching or even more quickly departing septuagenarian status. Why was this? Why had Raritan not propagated a younger generation of writers who wanted to write for them? Was it their fault? And will it matter, particularly for this younger generation that hasn’t heard of them, that they’re gone?

In Diary of a Bad Year, JC considers the distance between the “thudding, mechanical music favoured by the young” and the nineteenth-century art-song. His response to those who “querulously demand to know” why music cannot simply continue in the nineteenth-century symphonic tradition is blunt: “The animating principles of that music are dead and cannot be revived.” Anything that tried to would immediately sound anachronistic. Likewise, the principles that animated Raritan and its vision of intellectual life could not be sustained in the present moment and will not be revived in the foreseeable future. Money no longer exists for para-academic institutions, post-GI Bill largesse has long since disappeared, and the once general sense, “now weirdly archaic,” as Kermode recounted, “that literary criticism was extremely important, possibly the most important humanistic discipline, not only in the universities but also in the civilized world more generally,” has not so much faded as been chased out of town. Raritan’s shuttering, the deaths of so many of its contributors—including Jonathan Lear, who passed away suddenly and devastatingly as I was writing this—and the rapid aging of the rest of them, are confirmations of that thing we know now very well: an entire era of literary culture is at its end.

As the great oaks of this older culture have fallen, no one has quite grown tall enough to replace them, even amid the flourishing of the more recent little magazines. It’s hard to think of someone now who speaks, or at least intends to, with as much critical authority to a large general public as Harold Bloom, Frank Kermode or Edward Said once did. That the romantic geniuses, prophets and demiurges I met on my first forays all seemed to slowly fade from Raritan’s pages is no doubt because age has helped shed some of the scales from my eyes, but it is also a direct consequence of how the function of the humanities and the university has changed. Far from a liberal education whose ambition, as W.E.B. Du Bois trumpeted, is “delving for Truth, and searching out the hidden beauties of life, and learning the good of living,” contemporary institutions appear interested in solely vocational justifications for the humanities, hence the mass specialization, the single-minded focus on what we might disdainfully call “research outputs.” How could anyone today write the way Kermode did, with such singular, encyclopedic authority on everything from apocalyptic thought to Shakespeare to the Bible as literature, addressed to seemingly everyone from the mythic common reader to the highest reaches of the ivory towers?

And yet, as I grew older and began thinking about what it meant to take intellectual inquiry seriously in these times of economic precarity, cultural impotence and the incessant feeling of belatedness, I didn’t turn to Raritan, whose missives about living a life of the mind looked sepia-toned, straight from the Eighties. Instead, I turned to pieces like n+1’s “Cultural Revolution,” or the Baffler’s “What Are Intellectuals Good For?,” which addressed premises that Raritan was perhaps too old to confront head-on: that it is too late for literary criticism, too late for writing, and every publication and intellectual institution you know is either closing shop or being sold for parts. In other words, the future is foreclosed; what, then, is to be done?

●

Whenever a little magazine dies, a sea of obituaries and requiems seems to flood forth with desultory pronouncements about the state of literature, the reading public, the contemporary writers that always fall short of their predecessors. As n+1 co-founder Mark Greif put it in a Partisan Review retrospective, the moribund little magazine is always described as some crucial organ of mediation between haute intellectualism and the curious general public, whose death portends some looming crisis. The magazine is made to stand in for “the phantom flagship of ‘what we have lost.’” In these times when it seems so needed—other magazines are selling out, everything is speeding up, and the young people (God, are they even reading anymore?) are only getting stupider—we feel its absence grievously.

In response to the perennial question of the reading public, Poirier offered his own answer. In an editor’s note from 1982, entitled “Reading Anyone? Or, Is There a Reading Public?,” he strides through the popular attitudes of the day: books aren’t selling, education has been reduced to “gladiatorial training,” and a reading public able to rise to the occasion of an earlier public no longer exists, except, perhaps, in the academic community. (Sound familiar?) This, Poirier tells us, is not interesting. What is more compelling is the idea that a reading public can be produced; that, rather than expecting that public to demonstrate “a spontaneous interest in high culture,” more rarefied readers ought to remember that “people first need to know that they are endowed with cultural treasures before they can be expected to care about them.” (Thus Poirier’s decision to co-found the publisher Library of America, a Herculean effort to remind North American readers of their literary inheritance by collecting and publishing what might have otherwise scattered to the winds.) Performing—in other words, demonstrating—the work of reading, writing and knowing was, he felt, the only way to teach it, or to teach people to aspire to it.

As Greif concluded, a good magazine’s great accomplishment is that it directs its gaze “just slightly over the head[s]” of its readers, impelling them to go “up on tiptoe,” hoping to reach the heights that the writers themselves attain when they have truly risen to the occasion. At its best, when the various fantasy systems—those of the writers, the readers, the funders, even representatives of the “real world” of politics, business and government—could hammer out a deal, this collective conceit produced “an aspirational estimation of ‘the public.’” Aspirational here, Grief explains, doesn’t mean something moral like nobility or, worse, the pernicious commercial form appended to market-research words like “lifestyle”; rather, it refers to the sense that you can be better than you are. A good magazine constructs frameworks for understanding and clarifying the world, yes, but arguably its most crucial function is to initiate the reader, to give them a sense of how they could be. The root of my young attachment to Raritan was the great metaphysical ache I felt when encountering those pieces. Reading Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s “Epistemology of the Closet,” Adam Phillips’s “The Truth of Psychoanalysis” or James Longenbach’s “Disjunction in Poetry” felt like running after a bus, watching the distance between us grow and grow. All the same, it made me want to try.

There are a thousand and one ways to numb yourself to life, how you feel and what you say, each more effective than the last. To willingly grapple with language and the self, the kind of struggle I witnessed on the pages of Raritan and in myself while reading them, is hard work; harder yet is to convince other people of its necessity. But through that magazine, I began to see the glimmers of the edges of what real thinking could look like, thinking that was an activity, a battle, in which one confronted the limits of life, history and language itself. Raritan taught me to meet language—not just to scan but to read aloud the words on the page, let them linger, savor them—and then to listen for the agitation in myself, the pulse that would kick and quicken and, at times, drive me to my feet with the force of its exertion. Where was the pleasure? I learned to ask myself. Where was the pain? What forms of the self and what structures of the imagination did these words throw into sharp relief? When, how and why did my language betray me?

Attention to these confrontations had the curious effect of both contracting and dilating time. I became aware of how precarious and fleeting these moments were, how quickly these states seemed to take and leave me, and yet—at least I could watch it happen. Since discovering Raritan all those years ago, other magazines and writers have joined its ranks, and the range of models I have for good writing and good thinking has grown wide and promiscuous. Still, the journal’s folding closes the book on the first intellectual—and historical—tradition to which I ever wanted to belong.

Most of all, I will miss how Raritan made the non-urgent feel urgent, not by pegging its writing to current events or the shifting tides of discourse, but because good thinking exudes its own kind of clarion call for us to do the same—to listen, to look, to do as Rilke says and change our lives. I echo here the closing sentence of Randall Jarrell’s “Poets, Critics and Readers”: Read at whim! read at whim!

Image credit: Photos courtesy of Jackson Lears and Stephanie Volmer

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.