How should a person fuck? Ever since the publicly acknowledged possibilities exceeded “heterosexually, within a marriage, for the purposes of procreation,” this question has occupied generations of progressive-minded Americans, from the free-love utopians of nineteenth-century New York to the flower-child foot soldiers of the sexual revolution to the well-coiffed whistleblowers of #MeToo. Despite the combined efforts of this diverse cohort, definitive answers have not been forthcoming; if anything, we’re further from them than we’ve ever been. In my own lifetime, prescriptions for good sex have felt prone to contradictions and sudden reversals, while the obstacles preventing it—especially if you’re a woman—proliferate endlessly in the public imagination: rape culture, hookup culture, slut-shaming, “stealthing,” revenge porn, internet porn, age gaps, dating apps. Less think-pieced are the potentially lethal forces of transmisogyny and homophobia, perennial threats to women who deviate from an imagined cis, straight norm.

Evading violent or coercive sex is only half of the equation. For the conscientious lover, pleasure is its own minefield. Desire must not only be discovered and articulated (explicitly and exhaustively, depending on your interpretation of consent) but interrogated. And behind every preference lies a potentially unsavory connotation. Can a woman’s desire to submit to men be more than a latent expression of gendered self-hatred? Is it a concession to compulsory monogamy and the nuclear family to embark on only one sexual or romantic relationship at a time? If we accept that sex is no less imprinted with power and prejudice than any other aspect of social life, do we have “a duty to transfigure, as best we can, our desires” in more egalitarian directions, as philosopher Amia Srinivasan has asked? Or is it the case, as the critic Andrea Long Chu contends, that “nothing good comes of forcing desire to conform to political principle”?

Eve Cook, the narrator of Lillian Fishman’s novel Acts of Service and my generational contemporary—she is 27 when the book begins—admits to being confounded by our shared sexual-moral inheritance. “We had been made to believe that beauty was suspect, vanity was sin, desire was predatory,” she explains. These examples are archetypal: the lessons osmosed to her through the culture were always in the negative. “I had only been trained in what to avoid. No one had explained it to me very well—what mattered.” Stumbling around in this ethical vacuum, Eve discovers an attraction to other girls as a teenager, and the epiphany feels like absolution. “Queerness rose in my life like a faith,” she says. “Here was how I would know what was good to want.”

What’s good, Eve eventually concludes, is women who are “decent and principled”—women like her girlfriend Romi, a pediatrician and volunteer EMT, a holder of doors and carrier of umbrellas. Romi and Eve’s relationship is tender and earnest (they met on a crossword app) and their sex life seemingly robust, but amid this romantic idyll, Eve finds herself struggling with self-denial, the kind she believes is necessary to bring about the world she’d like to live in. On a superficial level, there is denial of the pride she takes in her conventionally attractive body, which she’s learned to disguise as more fashionable “self-respect.” But there’s also denial of “a truth so inadmissible in my life that I insisted even to myself that it was not the case”: the fact that “in the presence of a man who exuded power … I could feel myself growing soft and dimpling amiably under even a light touch of his attention.” Unfortunately for Eve, knowing what is good to want isn’t the same thing as actually wanting it. “I was constantly aware,” she tells us early on, “of how easily these years of internal censure might be unraveled.”

The form that unraveling takes is a dalliance with an unconventional couple, arranged after Eve impulsively posts a number of anonymous nude photos online. Olivia and Nathan are former college acquaintances and current coworkers at a wealth-management firm where they help the scions of some nameless dynasty make less reputationally toxic investments than their forebears. To be more precise, Nathan is Olivia’s boss. Like Eve, Olivia has mostly dated women, but she is the one who instigates the affair with Nathan. During a business trip, she shows up to his hotel room and begs, abjectly, to go down on him—a fantasy she’s harbored since their student days. When Eve comes into their orbit, the pair have only been sleeping together for a couple of months, but in that time, Olivia’s entire life has “changed in secret,” plunging the mousy aspiring painter into “a kind of fairy-tale bacchanalia.” She and Nathan aren’t boyfriend and girlfriend, and they hide their relationship at the office, where it’s against company policy. But this forbiddenness is an essential part of its erotic charge; sneaking around “transformed their workplace into a sexual landscape that was strange and spellbinding.”

Eve has secrets of her own: Olivia and Nathan don’t know about Romi, nor is she aware of them. But the trysts are a kind of unburdening for Eve all the same, allowing her to indulge in shameful sources of pleasure—not just her attraction to the kind of men who live in well-appointed apartments large enough to have wings, but the deeply held belief that she is special and deserving of worship; the “delight” she takes in being compared to other women and declared the winner. These pleasures are enabled partly by the form their group sex takes: for most of the novel, it hardly lives up to the term, resembling voyeurism more than anything else. Nathan fucks Eve, and Nathan fucks Olivia, with rare—and begrudging on Olivia’s part, Eve senses—contact between the two women. This stands in conflict with almost every value Eve has hitherto organized her life around. If she’s found queer love and sex intellectually rich and emotionally satisfying, that’s in part because it is also fraught: a process of mutual unlearning and shared anxieties, as she and her partners attempt to “avoid the seat of power” that skews relationships between men and women. Being with Nathan requires no such effort. On the contrary, it submerges Eve into “a state of grotesque candor, in which I had unfettered access not to the knowledge I had sought out and internalized but to the beliefs that had been instilled in me against my will.” Or, as Nathan himself puts it, “You think there’s something fucked up about sleeping with us. That’s part of why you like it so much.”

But transgression, as Fishman illustrates, has its own norms, and Eve isn’t necessarily less worried about saying or doing the wrong thing in front of her new paramours than she is with Romi. When she’s shocked to see Nathan slap Olivia across the face during sex, she chastises herself as “vanilla,” thinking, “Who was I to criticize consensual dynamics unfolding between adults?” And indeed, after she works up the courage to ask Nathan about the incident, his response is withering: “Are you really so bourgeois?” Later, during one of many searching conversations about the implications of their relationship, he is equally dismissive when Eve asks, “isn’t that just misogyny … That I want that, to be fucked by you like that?”

Why are you still thinking about all that bullshit? he said. I thought I cured you of that.

My life?

Not your life. Politics. This is your life.

That Eve shares a name with the avatar of original sin is obviously no accident. She also has another namesake, however: the California writer, muse and preeminent party girl Eve Babitz, allusions to whom are scattered throughout Fishman’s novel. Eve and her roommate Fatima even keep a quote from Babitz’s Slow Days, Fast Company pinned up by the front door of their apartment: “Anytime I want, I can forsake this dinner party and jump into real life.” Babitz manages to put into words an unspecified yearning on Eve’s part, the “sense that there was some depth I was avoiding, some sincerity or passion” lurking just below her quotidian existence as a loyal girlfriend and underpaid barista. But dinner parties and real life aren’t as easily distinguishable as she might hope. Nathan and Olivia seem to scramble the binary entirely. Are they selfish libertines or erotic philosophers? Nathan certainly views himself as an enlightened lover, insisting on sex as a site of revelation and pleasure as a tool of self-knowledge. Explaining his opposition to rules and safe words, to belaboring an encounter in advance, he asks Eve, “When you know from the beginning what’s allowed and what isn’t, what someone says they’ll want, what room is there for you to figure out what’s going to happen—or for her to discover that she wants something she didn’t realize? For the sex to actually open up something?”

The novel’s commitment to sexual theorizing is equal to its characters’, and it ultimately has the effect of making the sex it depicts feel less real—or at least less visceral and embodied. Acts of Service is noticeably light on anatomical language (see the overreliance on “entered,” the English language’s politest euphemism for “penetrated”), and Fishman tends to favor abstract rather than concrete adjectives, whether she’s describing foreplay or interiors, like Nathan’s living room, which has “a hushed quality, antiquated and almost modest.” When Nathan quotes from James Salter’s notoriously horny novel A Sport and a Pastime to describe what thrusting into Eve feels like—“an iron bar into water”—it comes almost as a shock—not for the line’s vulgarity, but for how strikingly it contrasts with Fishman’s more cerebral prose. In one representative passage, Eve recounts how she and Nathan “had sex in the engrossing way we sometimes did: unspeaking … He knew by the shape of my body the moment at which I felt utterly defenseless toward him.” If these intimate hours in apartments and hotel rooms represent contact with “real life,” it seems to exist mostly in the characters’ heads.

Until, that is, their metaphysical experiment is interrupted by a much less indeterminate force. More than a year into seeing each other, Nathan comes to Eve to ask for a favor, or more accurately, to provide a warning: he’s being sued by a woman who applied for a job at his firm and who claims she slept with him because he intimated it would help her get hired. Eve is going to be deposed, whether she likes it or not, because Nathan was at her place on the night in question, or so he claims. And while she sees little reason to doubt the other woman’s story is true—“I had witnessed Nathan’s misconduct; I had suspected he was willing to transgress beyond what went on with Olivia”—she’s not ready to renounce what he’s meant to her either.

One of Fishman’s keenest insights in Acts of Service is how context-dependent our understanding of normative sex is. It’s only because of Eve’s queer, vaguely anti-capitalist politics, for example, that sleeping with a rich guy in an expensive suit can feel like flouting convention. By the same token, words spoken to a lover in a postcoital daze sound different in a conference room packed with representatives of the legal system, that ultimate blunt instrument. When Eve is asked during her deposition whether she has ever felt manipulated by Nathan, she doesn’t know how to respond. The truth is that “not one day had passed since I’d met Nathan that I did not feel in some way under his thumb, yet I chose him again and again,” but there’s no way for her to win by being honest. Nathan has put her in an impossible position, and she senses that her testimony elicits disgust in the woman representing his plaintiff, who sees her not as belonging to a competing feminist tradition but as a gender traitor. Refusing to identify as Nathan’s victim, she becomes his co-conspirator, at least in the eyes of opposing counsel. Reading this scene, I thought of a line from n+1 editor Dayna Tortorici’s 2018 reflection on #MeToo: “As the adage goes: in the game of patriarchy, women aren’t the other team, they’re the ball.”

●

The unnamed narrator of Alyssa Songsiridej’s Little Rabbit proceeds from circumstances strikingly similar to Eve’s. Comfortable if professionally adrift, C (as her best friend Annie calls her) is ensconced in a queer social world when she embarks on a sexual relationship with an older man. In this case, much older: a choreographer in his fifties whom she met at a residency in Maine while working on a book about “a Central PA town haunted from below by demon-ghosts that were also, somehow, capitalism.” At the residency, C had taken against the choreographer: he monopolized the conversation at their communal dinners. But when they meet up in Boston on the occasion of a performance by his company, she perceives that a “chemical shift” has occurred: “I knew, right then, that I would sleep with him.” Soon after they reconnect, she contrives a pretext to visit him in New York and makes good on her word. They begin to see each other regularly, at his apartment in the city or his weekend retreat in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts, C’s body “responding like an obedient dog, chasing him all around the East Coast.”

The choreographer is far from her usual type: her last serious relationship was with a woman named Sheila who broke her heart, and the other men she’s been with were all “firm betas, quick to roll onto their backs and reveal their passing knowledge of gender studies.” If the choreographer’s profession, his past as a dancer, mark his masculinity as somewhat other, it is still more normative than she is accustomed to, bolstered by his age and professional success. C recognizes that “all the things the choreographer contained—man and older and prestige—expanded his capacity for damage,” and yet this perceived danger is not enough to put her off. In fact, it turns her on, flooding her with a feeling like “fright mixed with an unknown thrill.” The fright is not borne only of the possibility she’ll be hurt, but also of the way the relationship threatens to obliterate her own sense of herself, the kind of life and sex and she thought she wanted to pursue. It “knocked holes into the image I had of myself, the woman I used to be.”

That image is further compromised by C’s friend Annie, who lives with her in Somerville despite coming from the kind of family wealth that has an international real estate portfolio. Annie is a lesbian, a careerist and a writer, in that order. She works at a literary nonprofit (presumably a thinly fictionalized GrubStreet), and in addition to a fancy agent, she has “goals and a vision board and a clear idea of the points she wanted to put on her CV.” Annie has been C’s friend since college, and she helped pick up the pieces of her life after a devastating grad-school breakup. At times, C has even felt that the two of them “built all the beauty in our lives through the sheer force of our proximity.” But recently, C’s modest artistic successes—a novel published with a small press that immediately went bankrupt; the residency in Maine—have become a wedge between them. It’s in this context that the choreographer enters her life. Annie is immediately distrustful of his presence. When a female barista at their usual café gives C her number, Annie goads her to call, asking disparagingly if her hesitation is “because of him.”

With the choreographer’s encouragement, C agrees to the date: a chaste bike ride crowned by a single kiss, during which she “felt him, there. Not me kissing her, but the choreographer.” As an attempt to open up their relationship, the date is a failure on its own terms. What it does open up is a different kind of erotic possibility, one that elevates the existing imbalances between C and the choreographer, makes them exaggerated and intentional. Soon she is freed of the burden of telling herself “You don’t want that” about the overwhelming longing she has “to crawl to him, sit at his feet and surrender.” Their sex, already absorbing, grows more immersive, rougher. C’s arms become constellated with bruises, and she begins to crave a more complete subjugation: “His other hand went to my neck and found the place I wanted leashed, gripping it very lightly. No pressure, never, the air passing freely, but I sensed with thrill my proximity to real damage, how he held and controlled something crucial to my living.” For the holidays, he gifts her a pink silk tie that allows him to choke her without leaving a mark.

For the reader at least, this newfound intensity is tempered by the choreographer’s exaggerated solicitousness, even as the sex in Little Rabbit veers closer to the sadomasochistic. He is anxious to a fault about the prospect of doing C any lasting physical or psychic harm, perhaps an unlikely disposition for a dom. “I want you to feel good. I can’t do it if it makes you feel bad,” he tells her at one point. “Can’t it make me feel both?” she asks, reasonably. Songsiridej’s writing also occasionally suffers from the same euphemism problem as Fishman’s (genitals are “worked” so often that they ought to consider unionizing), but on the whole, her prose is refreshingly tactile, and she has an eye for sensuous details. Not just bodily ones, like the choreographer’s fingers gliding over “the wet muscle” of C’s tongue, but scents, taste and textures as well: the choreographer’s herbaceous shampoo; the bitter cocktails that he mixes; the photographs, ceramics and candleholders that litter his home. This material specificity is more than a flourish. Like Eve’s, C’s pursuit of sex is connected to fantasies of the real, but for her, sleeping with the choreographer has the opposite effect of Eve’s dalliance with Nathan and Olivia. Instead of making the rest of her life look flimsy by comparison, everything in it seems to possess a new heft. From her hands and feet to the objects in her room, the whole world is transformed in an instant: “it [feels] more real than anything.”

While her relationship with the choreographer remains for C “a long line of pleasure with no clear end,” the idiom in which she most often describes their sex is one of fragmentation: “I felt like I was cracking, breaking into him”; “That’s what it felt like, to have his body breaking into mine”; “What he’d done was crack something new inside of me and let it break the world.” The contradiction reads like an acknowledgment of the unnerving proximity of gratification and punishment, humiliation and catharsis. Ultimately, the relationship is threatening not for any danger it poses to C, but for the way it defies what Annie and people like her expect of sex and romance, “a narrative, a pattern of elegantly spaced beats between ‘bad’ and ‘good.’”

Until, suddenly, it doesn’t. The novel’s resolution consists of a cascade of just-so revelations on C’s part about the nature of her own craving for submission. Rather than an act of self-abnegation, she decides, offering herself wholly to the choreographer actually had been an exercise in extreme willpower that only the most dedicated are capable of; as she writes in a short story that’s accepted by a prestigious literary magazine, “No one understood … how it took everything to reach the edge and let go.” In case this meta-reference is too oblique, Songsiridej’s narration goes on to set out C’s epiphany in the starkest terms imaginable: “I thought I’d served him all this time, but really he served me.” It’s a disappointing retreat from the complexity that most of Little Rabbit pointedly courts, a deus ex machina of erotic empowerment that asks us to forget uncomfortable moments in the narrative where C’s desire is inextricable from her feelings of self-loathing, or the fact that the choreographer sometimes withheld force when she craved it most. I wanted to throw her own question, posed earlier in the novel, back at her: Can’t it be both? Little Rabbit may reach the edge, but it doesn’t let go.

Acts of Service, by contrast, is more content to dwell in ambivalence. At the end of the novel, Eve remains disturbed by the power of her experience with Nathan, yet she has an unshakable feeling of gratitude toward him, even in the lawsuit’s shadow. Tired of talking herself in circles about her own proclivities, she accepts that “it was fantasy to look for what was at my very core … as though there existed a sexual truth that was born in me, immune to every social lesson about what is sinister and what is sweet.”

It wouldn’t be unfair to read Acts of Service as a test case for the idea, advanced by Chu and others, that to corral desire within predetermined ideological parameters is to smother it—and to no real end. Certainly, the sex Eve has with Nathan and Olivia, which she initially views as ethically suspect, is more exciting, satisfying and ultimately enlightening than sex with her girlfriend Romi, whose competent fucking is just another extension of her virtuousness. The way Eve describes her new “indulgences,” though, shows that she has hardly managed to separate sex from political principle. A “life of adventure, romance, beauty, and pleasure,” she decides, is “the life I felt I was owed given all the concessions I was making to heterosexuality and capitalism and the monstrous city.” This language of trade-offs is partially tongue-in-cheek, but its persistence suggests a lingering sense of a cramped sexual horizon: “I wanted to be brand-new, to experience love and pleasure as though I had never been hurt and never felt fear. And what more could be owed to a woman than that?” Well, a lot, in fact. Eve’s new outlook provides a refuge from the enemies of eros, but it could also shade easily into complacency—the very “lethargy” that she earlier complains afflicts our complexity-obsessed generation.

It’s true that progressive scrutiny of modern sexuality often confuses cause and effect or overshoots the mark, caught up as it is in identity and individual choice. But recognizing these shortcomings, and resisting the easy moralism they imply, doesn’t mean we can afford to ignore the contradictions that sometimes arise between our personal desires and collective goals. Eve and C freely admit that their attraction to Nathan and the choreographer, respectively, derives in part from the structural position they occupy as straight men with money. And yet both women claim, if casually, a commitment to anti-capitalism and a feminist worldview. To point this out is not to argue that these characters—or their authors—are hypocrites, or have failed some kind of purity test, merely that the significance of the tension they illustrate cannot be wished away. Viewed honestly, it’s a conundrum that goes beyond the theoretical, with serious implications for any political movement that aims to challenge existing hierarchies of gender and class: How do we fight against social dynamics we’re libidinally invested in? Are we willing to sacrifice proven sources of pleasure in exchange for erotic possibilities it’s impossible to know in advance? (Material redistribution, after all, is likely to alter sexual scripts in a way that messaging campaigns can only dream of.) These questions, if they can ever be resolved, are too big for any one novel to answer. But the least we can do is ask.

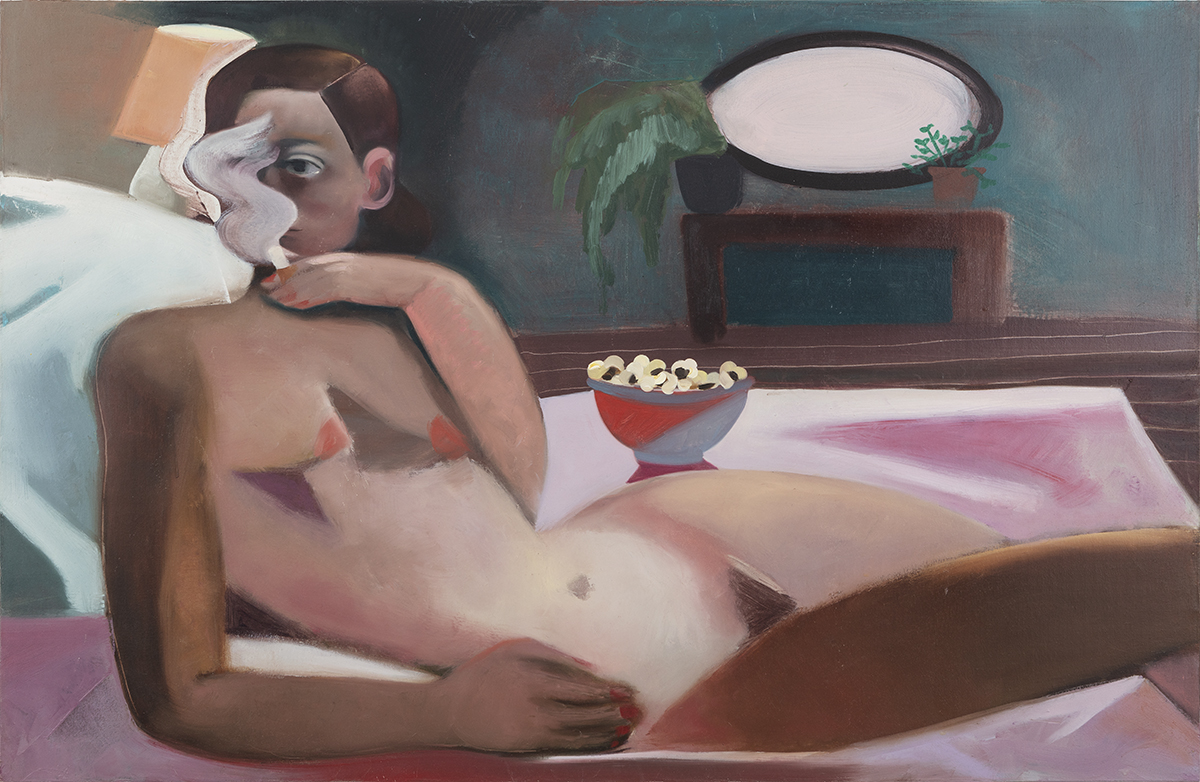

Art credit: Danielle Orchard. Morning Rituals (2022), oil on linen, photo by Guillaume Ziccarelli. Skinny Pop (2022), oil on linen, photo by Tanguy Beurdeley. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

How should a person fuck? Ever since the publicly acknowledged possibilities exceeded “heterosexually, within a marriage, for the purposes of procreation,” this question has occupied generations of progressive-minded Americans, from the free-love utopians of nineteenth-century New York to the flower-child foot soldiers of the sexual revolution to the well-coiffed whistleblowers of #MeToo. Despite the combined efforts of this diverse cohort, definitive answers have not been forthcoming; if anything, we’re further from them than we’ve ever been. In my own lifetime, prescriptions for good sex have felt prone to contradictions and sudden reversals, while the obstacles preventing it—especially if you’re a woman—proliferate endlessly in the public imagination: rape culture, hookup culture, slut-shaming, “stealthing,” revenge porn, internet porn, age gaps, dating apps. Less think-pieced are the potentially lethal forces of transmisogyny and homophobia, perennial threats to women who deviate from an imagined cis, straight norm.

Evading violent or coercive sex is only half of the equation. For the conscientious lover, pleasure is its own minefield. Desire must not only be discovered and articulated (explicitly and exhaustively, depending on your interpretation of consent) but interrogated. And behind every preference lies a potentially unsavory connotation. Can a woman’s desire to submit to men be more than a latent expression of gendered self-hatred? Is it a concession to compulsory monogamy and the nuclear family to embark on only one sexual or romantic relationship at a time? If we accept that sex is no less imprinted with power and prejudice than any other aspect of social life, do we have “a duty to transfigure, as best we can, our desires” in more egalitarian directions, as philosopher Amia Srinivasan has asked? Or is it the case, as the critic Andrea Long Chu contends, that “nothing good comes of forcing desire to conform to political principle”?

Eve Cook, the narrator of Lillian Fishman’s novel Acts of Service and my generational contemporary—she is 27 when the book begins—admits to being confounded by our shared sexual-moral inheritance. “We had been made to believe that beauty was suspect, vanity was sin, desire was predatory,” she explains. These examples are archetypal: the lessons osmosed to her through the culture were always in the negative. “I had only been trained in what to avoid. No one had explained it to me very well—what mattered.” Stumbling around in this ethical vacuum, Eve discovers an attraction to other girls as a teenager, and the epiphany feels like absolution. “Queerness rose in my life like a faith,” she says. “Here was how I would know what was good to want.”

What’s good, Eve eventually concludes, is women who are “decent and principled”—women like her girlfriend Romi, a pediatrician and volunteer EMT, a holder of doors and carrier of umbrellas. Romi and Eve’s relationship is tender and earnest (they met on a crossword app) and their sex life seemingly robust, but amid this romantic idyll, Eve finds herself struggling with self-denial, the kind she believes is necessary to bring about the world she’d like to live in. On a superficial level, there is denial of the pride she takes in her conventionally attractive body, which she’s learned to disguise as more fashionable “self-respect.” But there’s also denial of “a truth so inadmissible in my life that I insisted even to myself that it was not the case”: the fact that “in the presence of a man who exuded power … I could feel myself growing soft and dimpling amiably under even a light touch of his attention.” Unfortunately for Eve, knowing what is good to want isn’t the same thing as actually wanting it. “I was constantly aware,” she tells us early on, “of how easily these years of internal censure might be unraveled.”

The form that unraveling takes is a dalliance with an unconventional couple, arranged after Eve impulsively posts a number of anonymous nude photos online. Olivia and Nathan are former college acquaintances and current coworkers at a wealth-management firm where they help the scions of some nameless dynasty make less reputationally toxic investments than their forebears. To be more precise, Nathan is Olivia’s boss. Like Eve, Olivia has mostly dated women, but she is the one who instigates the affair with Nathan. During a business trip, she shows up to his hotel room and begs, abjectly, to go down on him—a fantasy she’s harbored since their student days. When Eve comes into their orbit, the pair have only been sleeping together for a couple of months, but in that time, Olivia’s entire life has “changed in secret,” plunging the mousy aspiring painter into “a kind of fairy-tale bacchanalia.” She and Nathan aren’t boyfriend and girlfriend, and they hide their relationship at the office, where it’s against company policy. But this forbiddenness is an essential part of its erotic charge; sneaking around “transformed their workplace into a sexual landscape that was strange and spellbinding.”

Eve has secrets of her own: Olivia and Nathan don’t know about Romi, nor is she aware of them. But the trysts are a kind of unburdening for Eve all the same, allowing her to indulge in shameful sources of pleasure—not just her attraction to the kind of men who live in well-appointed apartments large enough to have wings, but the deeply held belief that she is special and deserving of worship; the “delight” she takes in being compared to other women and declared the winner. These pleasures are enabled partly by the form their group sex takes: for most of the novel, it hardly lives up to the term, resembling voyeurism more than anything else. Nathan fucks Eve, and Nathan fucks Olivia, with rare—and begrudging on Olivia’s part, Eve senses—contact between the two women. This stands in conflict with almost every value Eve has hitherto organized her life around. If she’s found queer love and sex intellectually rich and emotionally satisfying, that’s in part because it is also fraught: a process of mutual unlearning and shared anxieties, as she and her partners attempt to “avoid the seat of power” that skews relationships between men and women. Being with Nathan requires no such effort. On the contrary, it submerges Eve into “a state of grotesque candor, in which I had unfettered access not to the knowledge I had sought out and internalized but to the beliefs that had been instilled in me against my will.” Or, as Nathan himself puts it, “You think there’s something fucked up about sleeping with us. That’s part of why you like it so much.”

But transgression, as Fishman illustrates, has its own norms, and Eve isn’t necessarily less worried about saying or doing the wrong thing in front of her new paramours than she is with Romi. When she’s shocked to see Nathan slap Olivia across the face during sex, she chastises herself as “vanilla,” thinking, “Who was I to criticize consensual dynamics unfolding between adults?” And indeed, after she works up the courage to ask Nathan about the incident, his response is withering: “Are you really so bourgeois?” Later, during one of many searching conversations about the implications of their relationship, he is equally dismissive when Eve asks, “isn’t that just misogyny … That I want that, to be fucked by you like that?”

That Eve shares a name with the avatar of original sin is obviously no accident. She also has another namesake, however: the California writer, muse and preeminent party girl Eve Babitz, allusions to whom are scattered throughout Fishman’s novel. Eve and her roommate Fatima even keep a quote from Babitz’s Slow Days, Fast Company pinned up by the front door of their apartment: “Anytime I want, I can forsake this dinner party and jump into real life.” Babitz manages to put into words an unspecified yearning on Eve’s part, the “sense that there was some depth I was avoiding, some sincerity or passion” lurking just below her quotidian existence as a loyal girlfriend and underpaid barista. But dinner parties and real life aren’t as easily distinguishable as she might hope. Nathan and Olivia seem to scramble the binary entirely. Are they selfish libertines or erotic philosophers? Nathan certainly views himself as an enlightened lover, insisting on sex as a site of revelation and pleasure as a tool of self-knowledge. Explaining his opposition to rules and safe words, to belaboring an encounter in advance, he asks Eve, “When you know from the beginning what’s allowed and what isn’t, what someone says they’ll want, what room is there for you to figure out what’s going to happen—or for her to discover that she wants something she didn’t realize? For the sex to actually open up something?”

The novel’s commitment to sexual theorizing is equal to its characters’, and it ultimately has the effect of making the sex it depicts feel less real—or at least less visceral and embodied. Acts of Service is noticeably light on anatomical language (see the overreliance on “entered,” the English language’s politest euphemism for “penetrated”), and Fishman tends to favor abstract rather than concrete adjectives, whether she’s describing foreplay or interiors, like Nathan’s living room, which has “a hushed quality, antiquated and almost modest.” When Nathan quotes from James Salter’s notoriously horny novel A Sport and a Pastime to describe what thrusting into Eve feels like—“an iron bar into water”—it comes almost as a shock—not for the line’s vulgarity, but for how strikingly it contrasts with Fishman’s more cerebral prose. In one representative passage, Eve recounts how she and Nathan “had sex in the engrossing way we sometimes did: unspeaking … He knew by the shape of my body the moment at which I felt utterly defenseless toward him.” If these intimate hours in apartments and hotel rooms represent contact with “real life,” it seems to exist mostly in the characters’ heads.

Until, that is, their metaphysical experiment is interrupted by a much less indeterminate force. More than a year into seeing each other, Nathan comes to Eve to ask for a favor, or more accurately, to provide a warning: he’s being sued by a woman who applied for a job at his firm and who claims she slept with him because he intimated it would help her get hired. Eve is going to be deposed, whether she likes it or not, because Nathan was at her place on the night in question, or so he claims. And while she sees little reason to doubt the other woman’s story is true—“I had witnessed Nathan’s misconduct; I had suspected he was willing to transgress beyond what went on with Olivia”—she’s not ready to renounce what he’s meant to her either.

One of Fishman’s keenest insights in Acts of Service is how context-dependent our understanding of normative sex is. It’s only because of Eve’s queer, vaguely anti-capitalist politics, for example, that sleeping with a rich guy in an expensive suit can feel like flouting convention. By the same token, words spoken to a lover in a postcoital daze sound different in a conference room packed with representatives of the legal system, that ultimate blunt instrument. When Eve is asked during her deposition whether she has ever felt manipulated by Nathan, she doesn’t know how to respond. The truth is that “not one day had passed since I’d met Nathan that I did not feel in some way under his thumb, yet I chose him again and again,” but there’s no way for her to win by being honest. Nathan has put her in an impossible position, and she senses that her testimony elicits disgust in the woman representing his plaintiff, who sees her not as belonging to a competing feminist tradition but as a gender traitor. Refusing to identify as Nathan’s victim, she becomes his co-conspirator, at least in the eyes of opposing counsel. Reading this scene, I thought of a line from n+1 editor Dayna Tortorici’s 2018 reflection on #MeToo: “As the adage goes: in the game of patriarchy, women aren’t the other team, they’re the ball.”

●

The unnamed narrator of Alyssa Songsiridej’s Little Rabbit proceeds from circumstances strikingly similar to Eve’s. Comfortable if professionally adrift, C (as her best friend Annie calls her) is ensconced in a queer social world when she embarks on a sexual relationship with an older man. In this case, much older: a choreographer in his fifties whom she met at a residency in Maine while working on a book about “a Central PA town haunted from below by demon-ghosts that were also, somehow, capitalism.” At the residency, C had taken against the choreographer: he monopolized the conversation at their communal dinners. But when they meet up in Boston on the occasion of a performance by his company, she perceives that a “chemical shift” has occurred: “I knew, right then, that I would sleep with him.” Soon after they reconnect, she contrives a pretext to visit him in New York and makes good on her word. They begin to see each other regularly, at his apartment in the city or his weekend retreat in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts, C’s body “responding like an obedient dog, chasing him all around the East Coast.”

The choreographer is far from her usual type: her last serious relationship was with a woman named Sheila who broke her heart, and the other men she’s been with were all “firm betas, quick to roll onto their backs and reveal their passing knowledge of gender studies.” If the choreographer’s profession, his past as a dancer, mark his masculinity as somewhat other, it is still more normative than she is accustomed to, bolstered by his age and professional success. C recognizes that “all the things the choreographer contained—man and older and prestige—expanded his capacity for damage,” and yet this perceived danger is not enough to put her off. In fact, it turns her on, flooding her with a feeling like “fright mixed with an unknown thrill.” The fright is not borne only of the possibility she’ll be hurt, but also of the way the relationship threatens to obliterate her own sense of herself, the kind of life and sex and she thought she wanted to pursue. It “knocked holes into the image I had of myself, the woman I used to be.”

That image is further compromised by C’s friend Annie, who lives with her in Somerville despite coming from the kind of family wealth that has an international real estate portfolio. Annie is a lesbian, a careerist and a writer, in that order. She works at a literary nonprofit (presumably a thinly fictionalized GrubStreet), and in addition to a fancy agent, she has “goals and a vision board and a clear idea of the points she wanted to put on her CV.” Annie has been C’s friend since college, and she helped pick up the pieces of her life after a devastating grad-school breakup. At times, C has even felt that the two of them “built all the beauty in our lives through the sheer force of our proximity.” But recently, C’s modest artistic successes—a novel published with a small press that immediately went bankrupt; the residency in Maine—have become a wedge between them. It’s in this context that the choreographer enters her life. Annie is immediately distrustful of his presence. When a female barista at their usual café gives C her number, Annie goads her to call, asking disparagingly if her hesitation is “because of him.”

With the choreographer’s encouragement, C agrees to the date: a chaste bike ride crowned by a single kiss, during which she “felt him, there. Not me kissing her, but the choreographer.” As an attempt to open up their relationship, the date is a failure on its own terms. What it does open up is a different kind of erotic possibility, one that elevates the existing imbalances between C and the choreographer, makes them exaggerated and intentional. Soon she is freed of the burden of telling herself “You don’t want that” about the overwhelming longing she has “to crawl to him, sit at his feet and surrender.” Their sex, already absorbing, grows more immersive, rougher. C’s arms become constellated with bruises, and she begins to crave a more complete subjugation: “His other hand went to my neck and found the place I wanted leashed, gripping it very lightly. No pressure, never, the air passing freely, but I sensed with thrill my proximity to real damage, how he held and controlled something crucial to my living.” For the holidays, he gifts her a pink silk tie that allows him to choke her without leaving a mark.

For the reader at least, this newfound intensity is tempered by the choreographer’s exaggerated solicitousness, even as the sex in Little Rabbit veers closer to the sadomasochistic. He is anxious to a fault about the prospect of doing C any lasting physical or psychic harm, perhaps an unlikely disposition for a dom. “I want you to feel good. I can’t do it if it makes you feel bad,” he tells her at one point. “Can’t it make me feel both?” she asks, reasonably. Songsiridej’s writing also occasionally suffers from the same euphemism problem as Fishman’s (genitals are “worked” so often that they ought to consider unionizing), but on the whole, her prose is refreshingly tactile, and she has an eye for sensuous details. Not just bodily ones, like the choreographer’s fingers gliding over “the wet muscle” of C’s tongue, but scents, taste and textures as well: the choreographer’s herbaceous shampoo; the bitter cocktails that he mixes; the photographs, ceramics and candleholders that litter his home. This material specificity is more than a flourish. Like Eve’s, C’s pursuit of sex is connected to fantasies of the real, but for her, sleeping with the choreographer has the opposite effect of Eve’s dalliance with Nathan and Olivia. Instead of making the rest of her life look flimsy by comparison, everything in it seems to possess a new heft. From her hands and feet to the objects in her room, the whole world is transformed in an instant: “it [feels] more real than anything.”

While her relationship with the choreographer remains for C “a long line of pleasure with no clear end,” the idiom in which she most often describes their sex is one of fragmentation: “I felt like I was cracking, breaking into him”; “That’s what it felt like, to have his body breaking into mine”; “What he’d done was crack something new inside of me and let it break the world.” The contradiction reads like an acknowledgment of the unnerving proximity of gratification and punishment, humiliation and catharsis. Ultimately, the relationship is threatening not for any danger it poses to C, but for the way it defies what Annie and people like her expect of sex and romance, “a narrative, a pattern of elegantly spaced beats between ‘bad’ and ‘good.’”

Until, suddenly, it doesn’t. The novel’s resolution consists of a cascade of just-so revelations on C’s part about the nature of her own craving for submission. Rather than an act of self-abnegation, she decides, offering herself wholly to the choreographer actually had been an exercise in extreme willpower that only the most dedicated are capable of; as she writes in a short story that’s accepted by a prestigious literary magazine, “No one understood … how it took everything to reach the edge and let go.” In case this meta-reference is too oblique, Songsiridej’s narration goes on to set out C’s epiphany in the starkest terms imaginable: “I thought I’d served him all this time, but really he served me.” It’s a disappointing retreat from the complexity that most of Little Rabbit pointedly courts, a deus ex machina of erotic empowerment that asks us to forget uncomfortable moments in the narrative where C’s desire is inextricable from her feelings of self-loathing, or the fact that the choreographer sometimes withheld force when she craved it most. I wanted to throw her own question, posed earlier in the novel, back at her: Can’t it be both? Little Rabbit may reach the edge, but it doesn’t let go.

Acts of Service, by contrast, is more content to dwell in ambivalence. At the end of the novel, Eve remains disturbed by the power of her experience with Nathan, yet she has an unshakable feeling of gratitude toward him, even in the lawsuit’s shadow. Tired of talking herself in circles about her own proclivities, she accepts that “it was fantasy to look for what was at my very core … as though there existed a sexual truth that was born in me, immune to every social lesson about what is sinister and what is sweet.”

It wouldn’t be unfair to read Acts of Service as a test case for the idea, advanced by Chu and others, that to corral desire within predetermined ideological parameters is to smother it—and to no real end. Certainly, the sex Eve has with Nathan and Olivia, which she initially views as ethically suspect, is more exciting, satisfying and ultimately enlightening than sex with her girlfriend Romi, whose competent fucking is just another extension of her virtuousness. The way Eve describes her new “indulgences,” though, shows that she has hardly managed to separate sex from political principle. A “life of adventure, romance, beauty, and pleasure,” she decides, is “the life I felt I was owed given all the concessions I was making to heterosexuality and capitalism and the monstrous city.” This language of trade-offs is partially tongue-in-cheek, but its persistence suggests a lingering sense of a cramped sexual horizon: “I wanted to be brand-new, to experience love and pleasure as though I had never been hurt and never felt fear. And what more could be owed to a woman than that?” Well, a lot, in fact. Eve’s new outlook provides a refuge from the enemies of eros, but it could also shade easily into complacency—the very “lethargy” that she earlier complains afflicts our complexity-obsessed generation.

It’s true that progressive scrutiny of modern sexuality often confuses cause and effect or overshoots the mark, caught up as it is in identity and individual choice. But recognizing these shortcomings, and resisting the easy moralism they imply, doesn’t mean we can afford to ignore the contradictions that sometimes arise between our personal desires and collective goals. Eve and C freely admit that their attraction to Nathan and the choreographer, respectively, derives in part from the structural position they occupy as straight men with money. And yet both women claim, if casually, a commitment to anti-capitalism and a feminist worldview. To point this out is not to argue that these characters—or their authors—are hypocrites, or have failed some kind of purity test, merely that the significance of the tension they illustrate cannot be wished away. Viewed honestly, it’s a conundrum that goes beyond the theoretical, with serious implications for any political movement that aims to challenge existing hierarchies of gender and class: How do we fight against social dynamics we’re libidinally invested in? Are we willing to sacrifice proven sources of pleasure in exchange for erotic possibilities it’s impossible to know in advance? (Material redistribution, after all, is likely to alter sexual scripts in a way that messaging campaigns can only dream of.) These questions, if they can ever be resolved, are too big for any one novel to answer. But the least we can do is ask.

Art credit: Danielle Orchard. Morning Rituals (2022), oil on linen, photo by Guillaume Ziccarelli. Skinny Pop (2022), oil on linen, photo by Tanguy Beurdeley. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.