Listen to an audio version of this essay:

With a clenched jaw, I watched the Rohingya girl on my computer screen describe her getaway.

“What happened?” asked the man filming her shakily.

“They killed everyone.”

“Everyone?”

She was calm—or perhaps just blank. She stared at him, her eyes dry. She looked about twelve and wore a striped purple top and dangling silver earrings. A young boy in her arms slept against her shoulder. “My mother. My brothers. They burned them. Everyone.”

I pounded the news desk with my fist and exhaled loudly, startling my colleague. News editors weren’t supposed to get worked up, least of all those at the international desk. After watching and reading wrenching things all day, we tended to cocoon ourselves in pragmatism. But something about the accounts of massacres and rapes and beheadings in the Burmese state of Rakhine had pierced that dispassion. My insides vibrated with an ulcerous sort of rage at the silence of newspapers, our State Department and the network at which I worked. I’d taken to accosting friends and turning political conversations into predicaments of righteous relativity: “Do you have any idea what’s happening in Myanmar right now? If you think our president’s words are offensive, where’s your concern for genocide?” Discussions turned into spats, political insight into performances of superiority.

Of course, I was only grinding my teeth and toying with my tie as I inhaled videos and articles from my cushioned office chair. On the news compilations I sent out daily to every show’s senior producers, I’d put the Rohingya as close to the top as possible without impinging on the implicit but sacrosanct prioritization of all things relating to our then just-inaugurated president. I’d use emotional language. I’d emphasize my outrage. But no questions would come my way. No requests for more material. The story was lost in the stew of foreign tragedies with which American news organizations could scarcely concern themselves even before the 2016 presidential election.

One day, I approached a senior producer with a different tack. I handed her a sheet of bullet points that soberly and quantitatively established the story’s significance. Below them, I listed video clips that would guarantee stimulating television. The next morning, the Rohingya were on our air for thirty portentous seconds.

●

I’d studied human rights as an undergraduate. The concentration was a touch offbeat but an effective conduit for my teenage ardor. For the first few semesters, I was most energized by questions of humanitarian intervention: Why didn’t the U.S. intervene in Cambodia and Rwanda? Why did they go into Bosnia and Somalia? What would it take to stop Darfur? The questions coalesced the spectacles of popular outrage, political prioritization and, finally, military action: the cinematically thrilling conquest of evil via bombs and tanks. The resulting ideology was interventionism, a cogent, satisfying ethic proselytized by the likes of Samantha Power and Richard Holbrooke and predicated on the maxim that we would “never again” stand by and watch while innocent people were wiped out en masse.

Eventually, our professors opted for exercises in disillusionment. The first time I read David Rieff’s A Bed for the Night, I was miffed by his air of agnosticism and his shrewd dismantling of intervention’s purported triumphs. The book, which Rieff started while reporting on the 1995 siege in Sarajevo and finished as the U.S. invaded Afghanistan, questioned the narrative of humanitarian aid as the obvious moral imperative of rich citizens to bestow upon poor, innocent civilians. Today’s victims, he wrote, by the chaotic logic of never-ending conflicts, can easily become tomorrow’s killers, and vice versa.

Rieff had many a bone to pick with the principles of dogged neutrality made famous by the International Committee of the Red Cross, but he found the politicization of aid more worrying: “Independent humanitarianism does many things well and some things badly, but the things it is now being called upon to do, such as helping to advance the cause of human rights, contributing to stopping wars, and furthering social justice, are beyond its competence.”

Advocates of humanitarian intervention, Rieff suggested, might be better off alleviating suffering in the immediate sense—providing those in need with “a bed for the night”—rather than casting florid political campaigns or the emotional rhetoric of civilizational saviorhood, both of which tended to “traffic in false hope.”

My first job out of college was with Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières), where this mentality, with some caveats, was further accentuated. “MSF offers assistance to people based solely on need, irrespective of race, religion, gender, or political affiliation,” one of the organization’s principles reads. It continues: “MSF’s commitment to independence, impartiality, and neutrality means that we will provide assistance to anyone who needs it.” Anyone. Because they’re known to treat militants and rape victims alike, MSF doctors tend to gain access to some of the world’s most dangerous and unstable areas. Clear, productive action, I learned that year, can require, even be served best by, dispassion.

●

There was, of course, good reason to be outraged at the massacres and mass displacements of the Rohingya. They were outrageous. I’d felt bubblings of commensurate anger when reading about the Syrians of Aleppo, the bombings of Shias in Iraq and Afghanistan and the famine in war-ravaged Yemen. At less monumental stories too: the serial warehouse fires in Bangladesh that kill dozens of women sewing clothes for H&M, the building collapses in the Indian state of Maharashtra, the calamitous oil tanker explosions in Nigeria. Disasters outside the “industrialized world” have a certain intensity of scale and cruelty, at least as they appear to what sociologist Stanley Cohen called the “ethnocentric, culturally imperialist ‘we’—educated and comfortable people living in stable societies.” Perhaps this is obvious, though it still sounds vaguely transgressive.

Speaking to graduate students at Columbia University in 2010, Nicholas Kristof, the famously disaster-attuned New York Times columnist, reportedly said, “I want to make people spill their coffee when they read the column. I do want them to go and donate, volunteer, whatever it may be, to help chip away at some of these problems.”

Getting Americans to care about overseas disasters, he admitted, took a bit of guile. He had to get “clinical” about it. He looked for Americans “doing good work” in places of war and conflict, because they were more relatable to his readers than local workers. More importantly, he’d come to realize that one person’s story, preferably a child’s, was more effective in mobilizing public empathy than illustrations of statistical magnitude. “The more victims, the less compassion,” he wrote in a 2007 column about the genocide in Darfur. “Time and again, we’ve seen that the human conscience just isn’t pricked by mass suffering, while an individual child (or puppy) in distress causes our hearts to flutter.”

Nowadays, Kristof writes less about international tragedies. In recent years, he penned a few columns about Yemen, Venezuela and global famine, but most were reserved for national affairs pertaining to the T-word. He’s still more outward-looking than the majority of opinion columnists at the Times, whose escalating preoccupations with the former president pushed foreign stories to the margins.

Indeed, even the newspaper’s front pages, which once upon a time might have projected some globalistic hierarchy of priorities, reserved its fire and brimstone primarily for that president and the slew of domestic groups and identities suffering under his reign. The Arab Spring gave way to Black Lives Matter. The number of oppressed groups around us proliferated, and the terms of their oppression hinged upon presumptions and categories very specific to American modes of identity and power—modes that were increasingly useful in rebutting a president who was passionately despised. As the fulcrum of liberal guilt swung to the domestic front, our guilt (and pity and anger) became both highly demanded and highly diffuse, but it also became partial to suffering with which we could viscerally identify.

●

A few months ago, I had lunch with one of my old college professors. His class about global crises in human rights had numbered among my most memorable, partly because of his own stories from the trenches—he’s a leading expert on Western Africa—and partly because of the way he’d pace between (and even upon) our desks, surprising us with ethical, logistical or anthropological dilemmas.

Over tuna sandwiches and pickles, he told me that, for the first time in nearly fifteen years, his students’ interests had begun to pivot away from the large-scale international issues on which his curriculum is based. Even when violence in countries like South Sudan, the Central African Republic, El Salvador and Somalia was addressed, he’d noticed an insistence upon looking at it through lenses that are more familiar, more personal, to the young, ardent American left. Like Kristof’s readers, the students, once a body of guiltily impersonal consciences, now sought the allure of Americanization, where even the remotest and thorniest conundrums were squeezed for overlaps with American conventions of injustice. They were happiest, it seemed, when issues could be linked to catchwords like white supremacy, racism, colonialism and patriarchy—when the students themselves could, in some fashion, be included in the suffering (or the culpability).

“Happiest” was the word my professor used, and while he undoubtedly meant something more like “most engaged,” I walked away with a portrait of this new style of empathy. It was anchored in the sorts of outrages that had fueled humanitarian interventionism, but the outrage now also appeared to be personalized, applicative and, to some degree, recreational.

●

Empathy’s etymological constituents invoke an inhabitation of feeling: en, “in”; pathos, “feeling,” and, before that, “suffering.”

Peculiarly enough, in the digital age, all feelings, certainly all suffering, matter. Or perhaps it’s fairer to say that in the digital age, a great variety of suffering is always contending for our attention. It all potentially matters. There is an endless buffet of it to photographically and videographically experience. But since much of our political engagement takes place on the same screens as everything else we do online—reading and writing, idle chatter, games, masturbation, television marathons—it is susceptible to the same reductions and recreationalizations. The digital space can open out into the enormity and complexity of the world just as easily as it can shrink, abridge or caricature it. Illusions of proximity can trick us into thinking we understand and commiserate with distant and distinct forms of suffering, and in this cozy domain, presumptuous empathy becomes a fashionable application.

All of our virtual shoe-sharing, moreover, is incumbent upon our immobility—we do a great deal of traveling through time and space, through gunfire and bombings and earthquakes, from our armchairs. There’s something disproportionately heartrending about this vividness, given our stationary vantages, the negligible distances between our screens and beds, and the ease with which we can make it both start and stop. It seems to throw traditions of guilt, immersion and certainly empathy off-kilter. A desperation for catharsis, driven by quiescent rage, can bring about the compulsion to emotionally overreact while keeping oddly idle.

When the pandemic hit New York City the first time, I fled my Harlem apartment and took refuge in a friend’s eight-bedroom mansion in Connecticut. It had a conference room, gym, wine cellar, pool house, tennis and basketball courts and a lake stocked with carp. Along with two other close friends, we spent our days working remotely and eating lavishly. Still, over dinners of salmon and well-aged wine, we’d rhapsodize about the apocalypse with a remarkable sense of fear and anxiety—remarkable because these emotions appeared to us to be reasonable, rooted in supposedly looming threats and dangers that we confronted, like almost everyone else, online.

We read the same news reports as the rest of the country about doctors and nurses on the front lines. We saw the same images of body bags and overcrowded wards. We heard the same thickly powdered news anchors telling us that anguish was now the national orthodoxy, and we were moved to believe we shared and maybe even wanted to share in the plight of the collective cherub.

●

hysterical: “an uncontrollable outburst of emotion or fear, often characterized by irrationality, laughter, weeping, etc.”

We should feel empathetic. It’s important. It’s admirable. It’s a gracious way to move through society. Moreover, to inhabit and commiserate with the suffering of others is surely central to the idea of human rights and the actuation of justice. It gives inadequacies and injustices the attention, by people who may not be directly affected by them, that they require in order to be effectively addressed. Yet, sometimes, in our digitally effected stupors, the feelings we associate with empathy can gateway into a new irrationalism—one that, in the shadows of earnest “outbursts of emotion,” draws from a catalogue of damaging confusions and conflations.

When we gratuitously import the suffering of others into our own self-conceptions, when we resist calculating a hierarchy of wrongs, when we catastrophize an issue rather than deliberate its solutions, when we allow a surfeit of zeal to scuttle pragmatic action, or when we lose sight of individuality—our own or that of the sufferers—in our rush to administer blanket sympathy, then our empathy may be said to have become “hysterical.”

●

As a news editor, I’ve watched many hours of video of besieged communities around the world. I’m often struck by the scenes of normalcy that seem to exist between the earth-shattering bombs, air strikes, massacres and diasporas: Rohingya women meticulously preparing meals for their families, Rohingya children fishing with their fathers, Iraqi Shias shopping for clothing during the holidays, schoolgirls in Aleppo singing Christmas carols. They demonstrate, in those instances, individuality, flickers of relatability, and some emancipation from the suffering their broad affiliation implies (to outsiders) with almost paradigmatic utility. I’m reminded that there’s something curiously reductive about assuming every member of a besieged community is defined by their most extreme political conditions, as if none exist on the margins of violence or experience ordinary things.

Inside the United States, where our humanitarian imperatives have evidently shifted, we are also prone to distilling our fellow citizens into emblems of adversity. Sometimes, we even do it to ourselves.

A few years ago, I acted in a devised, off-Broadway play about unconventional sexual identities. My castmates insisted I introduce myself by my most voguish signposts—“queer,” “immigrant,” “of color”—despite these neither resonating with my sense of individuality nor proving very useful in deciding how to invest myself in political and social causes. My castmates were intelligent and inventive, but they preferred the company of like-appearing people—or of those to whom they could assign some sort of numinous identitarian hardship. They’d talk to me and each other with gushing tenderness, as if we had all emerged from a trauma ward; what one of us said seemed less important than the transcendental openness and warmth with which it was collectively received.

They weren’t the first minorities in the United States to tell me I was a sufferer. In graduate school, a student affirmed I was a victim of racism, even though I’d never felt that way. My negative encounters in the city—grumpy baristas, rude taxi drivers, impatient liquor store clerks—were all conceivably due, she said, to my brownness. And if the offenders were non-white? I asked. Then, she replied confidently, it was because they were oppressed.

On a late night last July, while swiping into the 8th Street subway station, I jetted past a young man demanding that I let him through the exit gate. He managed to get in anyway, followed me to my seat on the train, and confronted me in front of the sleepy crowd: “Why the fuck didn’t you let me in? We’re brothers! N***as like us have to stick together!” He was black, I was brown, and this alone, it seemed, meant we were “in” something together. He was, I should add, wearing nice clothes and Apple AirPods, and while I didn’t necessarily understand anything about his circumstances, this made it easier to ascribe our encounter to the politics of capacious misfortune and compulsory outrage. My solidarity was expected to hinge not upon personalized deliberations but pre-chewed codes and conclusions.

My castmates, the student and even the man on the subway seemed to believe they were being empathetic toward me. But was this an effective way of understanding each other? How truthful, or useful, were the politics that permitted, valorized and even commanded such identifications?

●

In the past few years, a number of prominent writers have taken on the subject of empathy. Most did so in the contexts of art and literature, and often with some edge of criticism. Namwali Serpell’s “The Banality of Empathy,” for the New York Review of Books in 2019, is a case in point. For Serpell, a charismatic Zambian writer, the emotional empathy induced by art too readily brings about “the relishing of suffering from those who are safe from it.” We end up idly and creepily occupying subjects, especially marginalized ones, and the resultant emotional relief distracts us from “real inequities.” If even witnessing suffering firsthand doesn’t always “spark good deeds,” why, she asks, would art?

Serpell finds clarity in psychologist Paul Bloom’s distinction between cognitive empathy and emotional empathy. She likens the former—a project of thoughtful understanding that amounts to neither voyeurism nor occupation—to Hannah Arendt’s theory of “representative thinking.” In her 1967 essay “Truth and Politics,” Arendt says that “considering a given issue from different viewpoints” requires “disinterestedness, the liberation from one’s own private interests.” The title of Serpell’s essay evokes Arendt’s own famously contentious “Report on the Banality of Evil,” about the trial of Adolf Eichmann, implying about cathartic empathy some of the same heedless, mechanistic injuriousness that Arendt ascribed to doers of evil.

The judicious, distanced considerations of others that Serpell espouses offers a strong depiction of what unhysterical empathy ought to look like in real life: enough interest to be interested, but enough detachment to carefully imagine experiences and calculate wants and needs. As she puts it, “this need not be cold, just less … voracious.”

Still, the way Serpell frames binaries of oppression and otherness makes her susceptible to a few of the traps against which she cautions her readers. She’s aware of the dangers of reducing people to “single imaginary fabrications,” and yet racial identity seems to be the main lens she uses to determine suffering; many of her contenders for empathy merit it on this basis alone. Her example of contemporary art that preserves our political conscience is “The Venus Effect,” an enthusiastically bleak story by Violet Allen about a black protagonist who is shot dead by a cop in various scenarios. “We can offer a … deeper, rounder picture of human experience simply by casting characters in a different shade,” Serpell writes, speaking literally. Her axioms of injustice are noticeably Americanized—buzzing with those catchwords my professor observed in his classroom—just as her terms of otherness prioritize fixed and externalized features.

Serpell’s ideal of empathy may avoid emotionalism, but her essay doesn’t quite seem “disinterested” in Arendt’s sense of the word. Doubtless, our racial and ethnic identities can be relevant to our experiences of the world—they can bear intensely upon the way others see and empathize with us. At the same time, an overreliance on identitarian categories—the presumption that collectives and not individuals comprise the body politic—can, by diminishing the interior dimension of selfhood, pose another kind of obstacle to a scrupulously rational empathy.

●

In the last ten years, I have changed in ways both small and extreme. I also fluctuate internally on a daily, sometimes quarter-hourly, basis. Among my most dynamic, complex and even antagonizing conversations are those I have with myself. In her colossal investigation of consciousness, The Life of the Mind, Arendt calls this the “experience of the thinking ego.” More colorfully, she refers to such inward conversations as “the two-in-one”—my own, impassioned italics—“that Socrates discovered as the essence of thought and Plato translated into conceptual language as the soundless dialogue between me and myself.”

This capacity for self-interrogation, for being both questioner and answerer, is not an idiosyncrasy of solitude. The very essence of self-consciousness requires that we acknowledge and engage with ourselves, that we other ourselves.

“The two-in-one become One again when the outside world intrudes upon the thinker and cuts short the thinking process,” Arendt writes. When we are around others, to put it another way, we are seen as one—from the outside. Away from the world, we can turn once again into “the two-in-one.” We can use the peace and quiet to gain some distance from our bodily appearances and become conscious of ourselves.

When I assent to my complicated inner life, I do indeed find myself a puzzled spectator of my own body. Sometimes my body and I are in harmony, sometimes it is like a tug-of-war: I struggle to placate its whims, it struggles to accommodate my desire to think. While this makes for discomfiting moments, it has also permitted some liberation from impressions of physical and demographic uniformity. I don’t feel “brown” or “queer,” “male” or “foreign-born,” all the time—I don’t even feel them often.

The duality of the thinking ego, Arendt concludes, “explains the futility of the fashionable search for identity. Our modern identity crisis could be resolved only by never being alone and never trying to think.”

We ought to be careful, with this in mind, not to other each other in simplistic ways, nor to dramatize or diabolize at the expense of gray areas, as if we’re our true selves only when we are being seen and not when we are alone. Arendt insisted that every person possesses—and should engage with—a dialogical inner life. “It is a slippery fellow,” she wrote, “not only invisible to others but also, for the self, impalpable, impossible to grasp.”

A critical portion of each person, in other words, has no racial or sexual or national identity. It is ineffable. Empathizing in a productive rather than a hysterical direction might start with according each other a complex philosophical life in addition to political and physiological ones. There is something in each one of us that demands to be approached freshly every time.

When swiping into the subway station that summer night, my corpus, a hasty New Yorker, was neither relevant nor invited to the vibrant conversation I was having with myself (about, I’ll confess, whether Goethe would’ve adored Beyoncé like I do). I was not a bearded immigrant persecuted by omnipresent legal authorities any more than I initially saw the man at the gate as a pawn of his skin tone.

●

Many years ago, when President Obama was still in his first term, I visited David Rieff at his TriBeCa apartment, which shares an address with the Susan Sontag Foundation (Sontag was his mother). I remember the cavernous ceilings and lively décor—every surface and wall bore a striking painting, photograph or sculpture. After reading A Bed for the Night, I’d asked to interview him for my senior thesis, a study of civilian death tolls in conflict. I was particularly interested in numbers. How much did they matter? Was quantitative language the surest index of extremity and therefore prioritization?

“Well, you want me to judge things, and I don’t judge things in that way,” Rieff said, sitting back in a stuffed armchair and crossing a pair of magnificent feline-print boots. I pleaded a little. How about some dispassionate theorizing?

“Numbers are a way of getting attention, but they’re a way of getting attention for a very good reason,” he said. “Numbers are a kind of moral triage, if you will. And how would you run an emergency room without triage? How would you know which patient is in urgent need of attention?”

The severity of international conflicts gives us some indication of just how bad problems can get. This doesn’t mean we need only to gesture across the ocean every time a crisis at home solicits our attention. Or that empathy can serve no political function. It does, however, remind us that if everybody is a contender for our rapport, then nobody makes it to the emergency room. When it comes down to it, numbers throw cold water upon our impulses for dithyrambs and extravaganzas.

Of course, when we’re alone with our thinking egos, this sort of political utilitarianism can take a backseat. We can, we should, inhabit the experiences of others freely, discursively, even impractically. Sometimes, this might be the initial step toward political action. But when the time comes to consider externalized conditions and communal catastrophes, hysterical empathy threatens to obscure the way forward, precluding the possibility of nuanced analysis or reasonable action—of solutions that are boring, methodical and determinatively untheatrical. Pounding on desks and wallowing in righteous fury, the way I responded to the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar, is not just unhelpful. It can make the world unintelligible.

●

When I think back to the high-minded human rights major who yearned for exhibitions of justice, I find someone more compatible with the people I’ve encountered in recent years—my castmates, the student in my graduate class, even Namwali Serpell. But this is one of the ways in which I’ve changed. It’s not that I became disenchanted in the predictably nihilistic, post-collegiate vein (though maybe this played a small part). It’s that my experiences of animated, plural selfhood evinced conceptions of the individual as complex and irreducible, making me more prudent with my language and less eager to overidentify or project onto the struggles of others. With these changes, the politics of justice naturally sundered from the outrages of injustice. And problems of human rights, in the spirit of practicability, assumed cooler, more calculative proportions.

As I’ve found out, moreover, to be a recipient of emergency thinking’s hysteria-whipping currents is dehumanizing. It is aggressive. It is so humorless that one can’t help but wonder if mantras of penitence and aggrievement are merely the characteristic avocations of our time.

Sometimes, of course, heated, generalized, publicly demonstrated empathy can lead to remedial action. It can indicate that one’s politics are in the right place. Occasionally, it may be the only available response to an injustice that we witness virtually or otherwise. But when it obscures our understandings of root causes, of necessary distinctions, of the virtues of restraint or the complications of consciousness, it stymies responsible political action. It offends our notions of truth and accuracy. It goes as far, I think, as thwarting fundamental conceptions of the human experience.

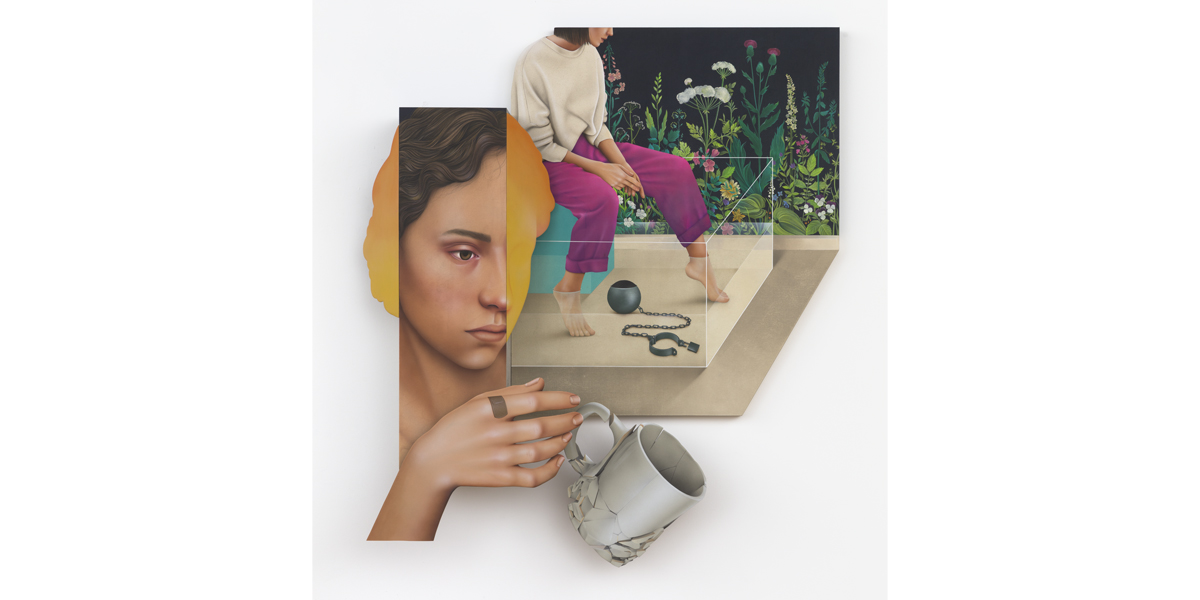

Art credits: Arghavan Khosravi. Black Rain, acrylic and cement on cotton canvas wrapped over shaped wood panel, wood cutout, elastic cord; 51.5 x 72 x 8 in.; 2021. Isn’t it time to celebrate your freedom?, acrylic and cement on cotton canvas wrapped over shaped wood panel, wood cutout; 62.625 x 58 x 8 in.; 2021. The Suspension, acrylic and cement on cotton canvas wrapped over shaped wood panel, wood cutout; 57.5 x 47 in.; 2020. All images courtesy of the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery.

Listen to an audio version of this essay:

With a clenched jaw, I watched the Rohingya girl on my computer screen describe her getaway.

“What happened?” asked the man filming her shakily.

“They killed everyone.”

“Everyone?”

She was calm—or perhaps just blank. She stared at him, her eyes dry. She looked about twelve and wore a striped purple top and dangling silver earrings. A young boy in her arms slept against her shoulder. “My mother. My brothers. They burned them. Everyone.”

I pounded the news desk with my fist and exhaled loudly, startling my colleague. News editors weren’t supposed to get worked up, least of all those at the international desk. After watching and reading wrenching things all day, we tended to cocoon ourselves in pragmatism. But something about the accounts of massacres and rapes and beheadings in the Burmese state of Rakhine had pierced that dispassion. My insides vibrated with an ulcerous sort of rage at the silence of newspapers, our State Department and the network at which I worked. I’d taken to accosting friends and turning political conversations into predicaments of righteous relativity: “Do you have any idea what’s happening in Myanmar right now? If you think our president’s words are offensive, where’s your concern for genocide?” Discussions turned into spats, political insight into performances of superiority.

Of course, I was only grinding my teeth and toying with my tie as I inhaled videos and articles from my cushioned office chair. On the news compilations I sent out daily to every show’s senior producers, I’d put the Rohingya as close to the top as possible without impinging on the implicit but sacrosanct prioritization of all things relating to our then just-inaugurated president. I’d use emotional language. I’d emphasize my outrage. But no questions would come my way. No requests for more material. The story was lost in the stew of foreign tragedies with which American news organizations could scarcely concern themselves even before the 2016 presidential election.

One day, I approached a senior producer with a different tack. I handed her a sheet of bullet points that soberly and quantitatively established the story’s significance. Below them, I listed video clips that would guarantee stimulating television. The next morning, the Rohingya were on our air for thirty portentous seconds.

●

I’d studied human rights as an undergraduate. The concentration was a touch offbeat but an effective conduit for my teenage ardor. For the first few semesters, I was most energized by questions of humanitarian intervention: Why didn’t the U.S. intervene in Cambodia and Rwanda? Why did they go into Bosnia and Somalia? What would it take to stop Darfur? The questions coalesced the spectacles of popular outrage, political prioritization and, finally, military action: the cinematically thrilling conquest of evil via bombs and tanks. The resulting ideology was interventionism, a cogent, satisfying ethic proselytized by the likes of Samantha Power and Richard Holbrooke and predicated on the maxim that we would “never again” stand by and watch while innocent people were wiped out en masse.

Eventually, our professors opted for exercises in disillusionment. The first time I read David Rieff’s A Bed for the Night, I was miffed by his air of agnosticism and his shrewd dismantling of intervention’s purported triumphs. The book, which Rieff started while reporting on the 1995 siege in Sarajevo and finished as the U.S. invaded Afghanistan, questioned the narrative of humanitarian aid as the obvious moral imperative of rich citizens to bestow upon poor, innocent civilians. Today’s victims, he wrote, by the chaotic logic of never-ending conflicts, can easily become tomorrow’s killers, and vice versa.

Rieff had many a bone to pick with the principles of dogged neutrality made famous by the International Committee of the Red Cross, but he found the politicization of aid more worrying: “Independent humanitarianism does many things well and some things badly, but the things it is now being called upon to do, such as helping to advance the cause of human rights, contributing to stopping wars, and furthering social justice, are beyond its competence.”

Advocates of humanitarian intervention, Rieff suggested, might be better off alleviating suffering in the immediate sense—providing those in need with “a bed for the night”—rather than casting florid political campaigns or the emotional rhetoric of civilizational saviorhood, both of which tended to “traffic in false hope.”

My first job out of college was with Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières), where this mentality, with some caveats, was further accentuated. “MSF offers assistance to people based solely on need, irrespective of race, religion, gender, or political affiliation,” one of the organization’s principles reads. It continues: “MSF’s commitment to independence, impartiality, and neutrality means that we will provide assistance to anyone who needs it.” Anyone. Because they’re known to treat militants and rape victims alike, MSF doctors tend to gain access to some of the world’s most dangerous and unstable areas. Clear, productive action, I learned that year, can require, even be served best by, dispassion.

●

There was, of course, good reason to be outraged at the massacres and mass displacements of the Rohingya. They were outrageous. I’d felt bubblings of commensurate anger when reading about the Syrians of Aleppo, the bombings of Shias in Iraq and Afghanistan and the famine in war-ravaged Yemen. At less monumental stories too: the serial warehouse fires in Bangladesh that kill dozens of women sewing clothes for H&M, the building collapses in the Indian state of Maharashtra, the calamitous oil tanker explosions in Nigeria. Disasters outside the “industrialized world” have a certain intensity of scale and cruelty, at least as they appear to what sociologist Stanley Cohen called the “ethnocentric, culturally imperialist ‘we’—educated and comfortable people living in stable societies.” Perhaps this is obvious, though it still sounds vaguely transgressive.

Speaking to graduate students at Columbia University in 2010, Nicholas Kristof, the famously disaster-attuned New York Times columnist, reportedly said, “I want to make people spill their coffee when they read the column. I do want them to go and donate, volunteer, whatever it may be, to help chip away at some of these problems.”

Getting Americans to care about overseas disasters, he admitted, took a bit of guile. He had to get “clinical” about it. He looked for Americans “doing good work” in places of war and conflict, because they were more relatable to his readers than local workers. More importantly, he’d come to realize that one person’s story, preferably a child’s, was more effective in mobilizing public empathy than illustrations of statistical magnitude. “The more victims, the less compassion,” he wrote in a 2007 column about the genocide in Darfur. “Time and again, we’ve seen that the human conscience just isn’t pricked by mass suffering, while an individual child (or puppy) in distress causes our hearts to flutter.”

Nowadays, Kristof writes less about international tragedies. In recent years, he penned a few columns about Yemen, Venezuela and global famine, but most were reserved for national affairs pertaining to the T-word. He’s still more outward-looking than the majority of opinion columnists at the Times, whose escalating preoccupations with the former president pushed foreign stories to the margins.

Indeed, even the newspaper’s front pages, which once upon a time might have projected some globalistic hierarchy of priorities, reserved its fire and brimstone primarily for that president and the slew of domestic groups and identities suffering under his reign. The Arab Spring gave way to Black Lives Matter. The number of oppressed groups around us proliferated, and the terms of their oppression hinged upon presumptions and categories very specific to American modes of identity and power—modes that were increasingly useful in rebutting a president who was passionately despised. As the fulcrum of liberal guilt swung to the domestic front, our guilt (and pity and anger) became both highly demanded and highly diffuse, but it also became partial to suffering with which we could viscerally identify.

●

A few months ago, I had lunch with one of my old college professors. His class about global crises in human rights had numbered among my most memorable, partly because of his own stories from the trenches—he’s a leading expert on Western Africa—and partly because of the way he’d pace between (and even upon) our desks, surprising us with ethical, logistical or anthropological dilemmas.

Over tuna sandwiches and pickles, he told me that, for the first time in nearly fifteen years, his students’ interests had begun to pivot away from the large-scale international issues on which his curriculum is based. Even when violence in countries like South Sudan, the Central African Republic, El Salvador and Somalia was addressed, he’d noticed an insistence upon looking at it through lenses that are more familiar, more personal, to the young, ardent American left. Like Kristof’s readers, the students, once a body of guiltily impersonal consciences, now sought the allure of Americanization, where even the remotest and thorniest conundrums were squeezed for overlaps with American conventions of injustice. They were happiest, it seemed, when issues could be linked to catchwords like white supremacy, racism, colonialism and patriarchy—when the students themselves could, in some fashion, be included in the suffering (or the culpability).

“Happiest” was the word my professor used, and while he undoubtedly meant something more like “most engaged,” I walked away with a portrait of this new style of empathy. It was anchored in the sorts of outrages that had fueled humanitarian interventionism, but the outrage now also appeared to be personalized, applicative and, to some degree, recreational.

●

Empathy’s etymological constituents invoke an inhabitation of feeling: en, “in”; pathos, “feeling,” and, before that, “suffering.”

Peculiarly enough, in the digital age, all feelings, certainly all suffering, matter. Or perhaps it’s fairer to say that in the digital age, a great variety of suffering is always contending for our attention. It all potentially matters. There is an endless buffet of it to photographically and videographically experience. But since much of our political engagement takes place on the same screens as everything else we do online—reading and writing, idle chatter, games, masturbation, television marathons—it is susceptible to the same reductions and recreationalizations. The digital space can open out into the enormity and complexity of the world just as easily as it can shrink, abridge or caricature it. Illusions of proximity can trick us into thinking we understand and commiserate with distant and distinct forms of suffering, and in this cozy domain, presumptuous empathy becomes a fashionable application.

All of our virtual shoe-sharing, moreover, is incumbent upon our immobility—we do a great deal of traveling through time and space, through gunfire and bombings and earthquakes, from our armchairs. There’s something disproportionately heartrending about this vividness, given our stationary vantages, the negligible distances between our screens and beds, and the ease with which we can make it both start and stop. It seems to throw traditions of guilt, immersion and certainly empathy off-kilter. A desperation for catharsis, driven by quiescent rage, can bring about the compulsion to emotionally overreact while keeping oddly idle.

When the pandemic hit New York City the first time, I fled my Harlem apartment and took refuge in a friend’s eight-bedroom mansion in Connecticut. It had a conference room, gym, wine cellar, pool house, tennis and basketball courts and a lake stocked with carp. Along with two other close friends, we spent our days working remotely and eating lavishly. Still, over dinners of salmon and well-aged wine, we’d rhapsodize about the apocalypse with a remarkable sense of fear and anxiety—remarkable because these emotions appeared to us to be reasonable, rooted in supposedly looming threats and dangers that we confronted, like almost everyone else, online.

We read the same news reports as the rest of the country about doctors and nurses on the front lines. We saw the same images of body bags and overcrowded wards. We heard the same thickly powdered news anchors telling us that anguish was now the national orthodoxy, and we were moved to believe we shared and maybe even wanted to share in the plight of the collective cherub.

●

hysterical: “an uncontrollable outburst of emotion or fear, often characterized by irrationality, laughter, weeping, etc.”

We should feel empathetic. It’s important. It’s admirable. It’s a gracious way to move through society. Moreover, to inhabit and commiserate with the suffering of others is surely central to the idea of human rights and the actuation of justice. It gives inadequacies and injustices the attention, by people who may not be directly affected by them, that they require in order to be effectively addressed. Yet, sometimes, in our digitally effected stupors, the feelings we associate with empathy can gateway into a new irrationalism—one that, in the shadows of earnest “outbursts of emotion,” draws from a catalogue of damaging confusions and conflations.

When we gratuitously import the suffering of others into our own self-conceptions, when we resist calculating a hierarchy of wrongs, when we catastrophize an issue rather than deliberate its solutions, when we allow a surfeit of zeal to scuttle pragmatic action, or when we lose sight of individuality—our own or that of the sufferers—in our rush to administer blanket sympathy, then our empathy may be said to have become “hysterical.”

●

As a news editor, I’ve watched many hours of video of besieged communities around the world. I’m often struck by the scenes of normalcy that seem to exist between the earth-shattering bombs, air strikes, massacres and diasporas: Rohingya women meticulously preparing meals for their families, Rohingya children fishing with their fathers, Iraqi Shias shopping for clothing during the holidays, schoolgirls in Aleppo singing Christmas carols. They demonstrate, in those instances, individuality, flickers of relatability, and some emancipation from the suffering their broad affiliation implies (to outsiders) with almost paradigmatic utility. I’m reminded that there’s something curiously reductive about assuming every member of a besieged community is defined by their most extreme political conditions, as if none exist on the margins of violence or experience ordinary things.

Inside the United States, where our humanitarian imperatives have evidently shifted, we are also prone to distilling our fellow citizens into emblems of adversity. Sometimes, we even do it to ourselves.

A few years ago, I acted in a devised, off-Broadway play about unconventional sexual identities. My castmates insisted I introduce myself by my most voguish signposts—“queer,” “immigrant,” “of color”—despite these neither resonating with my sense of individuality nor proving very useful in deciding how to invest myself in political and social causes. My castmates were intelligent and inventive, but they preferred the company of like-appearing people—or of those to whom they could assign some sort of numinous identitarian hardship. They’d talk to me and each other with gushing tenderness, as if we had all emerged from a trauma ward; what one of us said seemed less important than the transcendental openness and warmth with which it was collectively received.

They weren’t the first minorities in the United States to tell me I was a sufferer. In graduate school, a student affirmed I was a victim of racism, even though I’d never felt that way. My negative encounters in the city—grumpy baristas, rude taxi drivers, impatient liquor store clerks—were all conceivably due, she said, to my brownness. And if the offenders were non-white? I asked. Then, she replied confidently, it was because they were oppressed.

On a late night last July, while swiping into the 8th Street subway station, I jetted past a young man demanding that I let him through the exit gate. He managed to get in anyway, followed me to my seat on the train, and confronted me in front of the sleepy crowd: “Why the fuck didn’t you let me in? We’re brothers! N***as like us have to stick together!” He was black, I was brown, and this alone, it seemed, meant we were “in” something together. He was, I should add, wearing nice clothes and Apple AirPods, and while I didn’t necessarily understand anything about his circumstances, this made it easier to ascribe our encounter to the politics of capacious misfortune and compulsory outrage. My solidarity was expected to hinge not upon personalized deliberations but pre-chewed codes and conclusions.

My castmates, the student and even the man on the subway seemed to believe they were being empathetic toward me. But was this an effective way of understanding each other? How truthful, or useful, were the politics that permitted, valorized and even commanded such identifications?

●

In the past few years, a number of prominent writers have taken on the subject of empathy. Most did so in the contexts of art and literature, and often with some edge of criticism. Namwali Serpell’s “The Banality of Empathy,” for the New York Review of Books in 2019, is a case in point. For Serpell, a charismatic Zambian writer, the emotional empathy induced by art too readily brings about “the relishing of suffering from those who are safe from it.” We end up idly and creepily occupying subjects, especially marginalized ones, and the resultant emotional relief distracts us from “real inequities.” If even witnessing suffering firsthand doesn’t always “spark good deeds,” why, she asks, would art?

Serpell finds clarity in psychologist Paul Bloom’s distinction between cognitive empathy and emotional empathy. She likens the former—a project of thoughtful understanding that amounts to neither voyeurism nor occupation—to Hannah Arendt’s theory of “representative thinking.” In her 1967 essay “Truth and Politics,” Arendt says that “considering a given issue from different viewpoints” requires “disinterestedness, the liberation from one’s own private interests.” The title of Serpell’s essay evokes Arendt’s own famously contentious “Report on the Banality of Evil,” about the trial of Adolf Eichmann, implying about cathartic empathy some of the same heedless, mechanistic injuriousness that Arendt ascribed to doers of evil.

The judicious, distanced considerations of others that Serpell espouses offers a strong depiction of what unhysterical empathy ought to look like in real life: enough interest to be interested, but enough detachment to carefully imagine experiences and calculate wants and needs. As she puts it, “this need not be cold, just less … voracious.”

Still, the way Serpell frames binaries of oppression and otherness makes her susceptible to a few of the traps against which she cautions her readers. She’s aware of the dangers of reducing people to “single imaginary fabrications,” and yet racial identity seems to be the main lens she uses to determine suffering; many of her contenders for empathy merit it on this basis alone. Her example of contemporary art that preserves our political conscience is “The Venus Effect,” an enthusiastically bleak story by Violet Allen about a black protagonist who is shot dead by a cop in various scenarios. “We can offer a … deeper, rounder picture of human experience simply by casting characters in a different shade,” Serpell writes, speaking literally. Her axioms of injustice are noticeably Americanized—buzzing with those catchwords my professor observed in his classroom—just as her terms of otherness prioritize fixed and externalized features.

Serpell’s ideal of empathy may avoid emotionalism, but her essay doesn’t quite seem “disinterested” in Arendt’s sense of the word. Doubtless, our racial and ethnic identities can be relevant to our experiences of the world—they can bear intensely upon the way others see and empathize with us. At the same time, an overreliance on identitarian categories—the presumption that collectives and not individuals comprise the body politic—can, by diminishing the interior dimension of selfhood, pose another kind of obstacle to a scrupulously rational empathy.

●

In the last ten years, I have changed in ways both small and extreme. I also fluctuate internally on a daily, sometimes quarter-hourly, basis. Among my most dynamic, complex and even antagonizing conversations are those I have with myself. In her colossal investigation of consciousness, The Life of the Mind, Arendt calls this the “experience of the thinking ego.” More colorfully, she refers to such inward conversations as “the two-in-one”—my own, impassioned italics—“that Socrates discovered as the essence of thought and Plato translated into conceptual language as the soundless dialogue between me and myself.”

This capacity for self-interrogation, for being both questioner and answerer, is not an idiosyncrasy of solitude. The very essence of self-consciousness requires that we acknowledge and engage with ourselves, that we other ourselves.

“The two-in-one become One again when the outside world intrudes upon the thinker and cuts short the thinking process,” Arendt writes. When we are around others, to put it another way, we are seen as one—from the outside. Away from the world, we can turn once again into “the two-in-one.” We can use the peace and quiet to gain some distance from our bodily appearances and become conscious of ourselves.

When I assent to my complicated inner life, I do indeed find myself a puzzled spectator of my own body. Sometimes my body and I are in harmony, sometimes it is like a tug-of-war: I struggle to placate its whims, it struggles to accommodate my desire to think. While this makes for discomfiting moments, it has also permitted some liberation from impressions of physical and demographic uniformity. I don’t feel “brown” or “queer,” “male” or “foreign-born,” all the time—I don’t even feel them often.

The duality of the thinking ego, Arendt concludes, “explains the futility of the fashionable search for identity. Our modern identity crisis could be resolved only by never being alone and never trying to think.”

We ought to be careful, with this in mind, not to other each other in simplistic ways, nor to dramatize or diabolize at the expense of gray areas, as if we’re our true selves only when we are being seen and not when we are alone. Arendt insisted that every person possesses—and should engage with—a dialogical inner life. “It is a slippery fellow,” she wrote, “not only invisible to others but also, for the self, impalpable, impossible to grasp.”

A critical portion of each person, in other words, has no racial or sexual or national identity. It is ineffable. Empathizing in a productive rather than a hysterical direction might start with according each other a complex philosophical life in addition to political and physiological ones. There is something in each one of us that demands to be approached freshly every time.

When swiping into the subway station that summer night, my corpus, a hasty New Yorker, was neither relevant nor invited to the vibrant conversation I was having with myself (about, I’ll confess, whether Goethe would’ve adored Beyoncé like I do). I was not a bearded immigrant persecuted by omnipresent legal authorities any more than I initially saw the man at the gate as a pawn of his skin tone.

●

Many years ago, when President Obama was still in his first term, I visited David Rieff at his TriBeCa apartment, which shares an address with the Susan Sontag Foundation (Sontag was his mother). I remember the cavernous ceilings and lively décor—every surface and wall bore a striking painting, photograph or sculpture. After reading A Bed for the Night, I’d asked to interview him for my senior thesis, a study of civilian death tolls in conflict. I was particularly interested in numbers. How much did they matter? Was quantitative language the surest index of extremity and therefore prioritization?

“Well, you want me to judge things, and I don’t judge things in that way,” Rieff said, sitting back in a stuffed armchair and crossing a pair of magnificent feline-print boots. I pleaded a little. How about some dispassionate theorizing?

“Numbers are a way of getting attention, but they’re a way of getting attention for a very good reason,” he said. “Numbers are a kind of moral triage, if you will. And how would you run an emergency room without triage? How would you know which patient is in urgent need of attention?”

The severity of international conflicts gives us some indication of just how bad problems can get. This doesn’t mean we need only to gesture across the ocean every time a crisis at home solicits our attention. Or that empathy can serve no political function. It does, however, remind us that if everybody is a contender for our rapport, then nobody makes it to the emergency room. When it comes down to it, numbers throw cold water upon our impulses for dithyrambs and extravaganzas.

Of course, when we’re alone with our thinking egos, this sort of political utilitarianism can take a backseat. We can, we should, inhabit the experiences of others freely, discursively, even impractically. Sometimes, this might be the initial step toward political action. But when the time comes to consider externalized conditions and communal catastrophes, hysterical empathy threatens to obscure the way forward, precluding the possibility of nuanced analysis or reasonable action—of solutions that are boring, methodical and determinatively untheatrical. Pounding on desks and wallowing in righteous fury, the way I responded to the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar, is not just unhelpful. It can make the world unintelligible.

●

When I think back to the high-minded human rights major who yearned for exhibitions of justice, I find someone more compatible with the people I’ve encountered in recent years—my castmates, the student in my graduate class, even Namwali Serpell. But this is one of the ways in which I’ve changed. It’s not that I became disenchanted in the predictably nihilistic, post-collegiate vein (though maybe this played a small part). It’s that my experiences of animated, plural selfhood evinced conceptions of the individual as complex and irreducible, making me more prudent with my language and less eager to overidentify or project onto the struggles of others. With these changes, the politics of justice naturally sundered from the outrages of injustice. And problems of human rights, in the spirit of practicability, assumed cooler, more calculative proportions.

As I’ve found out, moreover, to be a recipient of emergency thinking’s hysteria-whipping currents is dehumanizing. It is aggressive. It is so humorless that one can’t help but wonder if mantras of penitence and aggrievement are merely the characteristic avocations of our time.

Sometimes, of course, heated, generalized, publicly demonstrated empathy can lead to remedial action. It can indicate that one’s politics are in the right place. Occasionally, it may be the only available response to an injustice that we witness virtually or otherwise. But when it obscures our understandings of root causes, of necessary distinctions, of the virtues of restraint or the complications of consciousness, it stymies responsible political action. It offends our notions of truth and accuracy. It goes as far, I think, as thwarting fundamental conceptions of the human experience.

Art credits: Arghavan Khosravi. Black Rain, acrylic and cement on cotton canvas wrapped over shaped wood panel, wood cutout, elastic cord; 51.5 x 72 x 8 in.; 2021. Isn’t it time to celebrate your freedom?, acrylic and cement on cotton canvas wrapped over shaped wood panel, wood cutout; 62.625 x 58 x 8 in.; 2021. The Suspension, acrylic and cement on cotton canvas wrapped over shaped wood panel, wood cutout; 57.5 x 47 in.; 2020. All images courtesy of the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery.

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.