In December 2018, I found myself unexpectedly pregnant. I have three children, the oldest of whom is in high school, and I had not planned on negotiating the difficulties of pregnancy and early childhood at this point in my life and career. Adding a decade or so of intensive child-raising to what I’d already committed to meant curtailing my ability to achieve what I both want and need to achieve in my finite lifetime. I asked myself, what are children for?

Under those circumstances, the question takes a practical, deliberative form: should I have an abortion? I discussed my predicament with a number of people: my husband, friends, family members and even a conference room full of philosophers at the annual Eastern American Philosophical Association meeting. I discovered that people—even committed pro-choicers—cannot handle this question. A friend wrote: “I do not believe in any kind of soul, so for me there is clearly a window where ‘the A-word’ is not a moral dilemma for a woman.” Notice: he thinks there is no moral dilemma, but nonetheless he cannot bring himself to use “the A-word.”

At the philosophy conference I was one of three speakers on a panel. In the question period—this was a first for me—not a single question was directed at me. Indeed, it seemed to me as I scanned the room that the members of the audience were avoiding making eye contact with me. At the end of the session, one person came up to talk to me—not to discuss the arguments I had made, or follow up on some point needing clarification—but to assure me that she would keep what I had revealed confidential.

I think if instead of “I am considering having an abortion” I had said, “I have had an abortion” or “I am planning to have an abortion,” they could have managed the overshare much better. I would have encountered a supportive, sympathetic response, which they could have set aside to focus on the (interesting!) philosophical point about misogyny and domination that I was using my own predicament to illustrate. If I had allowed them to “read” my situation as one of ridding oneself of a clump of cells, they could have moved past the personal narrative to the philosophical problem.

Or if, instead, I had confronted them with “I have had a miscarriage”—for that is, as a matter of fact, how the pregnancy, and my deliberations about whether to continue it, would end—they would have empathized over my loss of a child. They would have been quick to concede that I had lost a baby—even though, of course, the most likely cause of a miscarriage is precisely a degree of genetic abnormality incompatible with life. From a biological point of view, “clump of cells” is a better descriptor for what is miscarried than for what, in an otherwise healthy pregnancy, is aborted.

But I doubt many women who miscarry adopt this biological point of view. My first miscarriage was two years earlier, and if I had told you about it, you could’ve responded with a less confused form of empathy than what you are probably feeling about the more recent second one. I wanted that baby, unequivocally. At barely two months pregnant I was already happily inhabiting a life in which a fourth child was coming. The miscarriage plunged me, instead, into one in which the upcoming years loomed bland, empty, shapeless. I had just been awarded tenure, and it felt like my life was over: I couldn’t see a future, couldn’t see goals, bench points, markers of meaning. My husband said that I seemed dead for a while.

Looking back on that first miscarriage, I can now see that I failed to appreciate the blessing that is unconflicted mourning. The second time around, I found myself faced with new questions: How do I mourn a child I didn’t know I wanted? A child I might, for all I knew, have been about to kill? I couldn’t make sense of my situation, I couldn’t articulate my loss as a loss or not, as cells or baby. So I am sympathetic with the audience of my APA talk, who couldn’t entertain the thought of a maybe-entity poised on the razor’s edge of cells and baby. There isn’t space for half a person. It’s an unthinkable situation.

And yet, sometimes we must think about such things nonetheless. And by “we,” I mean, first and foremost, women. Many of us become, by biological necessity, embroiled in impossible calculations involving half-people, almost humans, ghost babies.

My 2018 pregnancy didn’t last long: ten weeks, ending in January 2019. The miscarriage happened while I was traveling, in New York City. It began in the basement bathroom of the New York Public Library, where I sought refuge when I realized I wouldn’t make it to my hotel in time. There was an absolutely shocking amount of blood, and somehow it was also everywhere. All over me, all over the bathroom stall. How did it get on the door?

I thought about seeking out cleaning supplies, but the bathroom was humming and buzzing with mothers escorting children, and I couldn’t risk any of them catching a glimpse of what looked like nothing so much as a crime scene. So I had to clean the stall with only the materials inside it, which—well, you know what there is inside a women’s bathroom stall. Not much. I did my best. Then I waited for a pause in footsteps, and dashed to the sink for my Lady Macbeth moment, frantically scrubbing away at my hands so that most of the blood would be gone by the time the next person entered. How did I feel? At that time, my thoughts were mostly about blood volume (am I dying?) and location (how could I do this to the library?). I have spent many wonderful hours in the reading room upstairs, and I couldn’t help but think something like “This is no place for a miscarriage. My desecration of this sacred space is uncalled for.” I left the library and headed for my hotel room to bleed some more.

There is something distinctively miserable about sitting in a hotel room, cramping and bleeding, pretending you are “doing something” when really you are just undergoing something you don’t know how to conceptualize. I thought about my misery, and it hit me that there is something else that is difficult to conceptualize: modern art. I like it when things match, in every sense. So I put on my most blood-colored clothing and headed to the Guggenheim.

The handy thing about the Guggenheim is that there is a single-user bathroom at each full revolution. I made good use of them, to the sometime irritation of door-banging tourists speaking a variety of languages. Aside from the bathrooms, there was also the exhibition: Hilma af Klint (1862-1944), a Swedish pioneer of abstraction who worked largely in isolation from her artistic contemporaries. I suspect that few humans have had the experience I had that day: communing with an artistic visionary while miscarrying a baby you would never know whether you wanted. Let me try to communicate to you what that is like.

●

Af Klint’s art grew out of a practice of automatic drawing associated with séances, and answered to the call of High Masters whose imagined commissions guided her creations:

The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brushstroke.

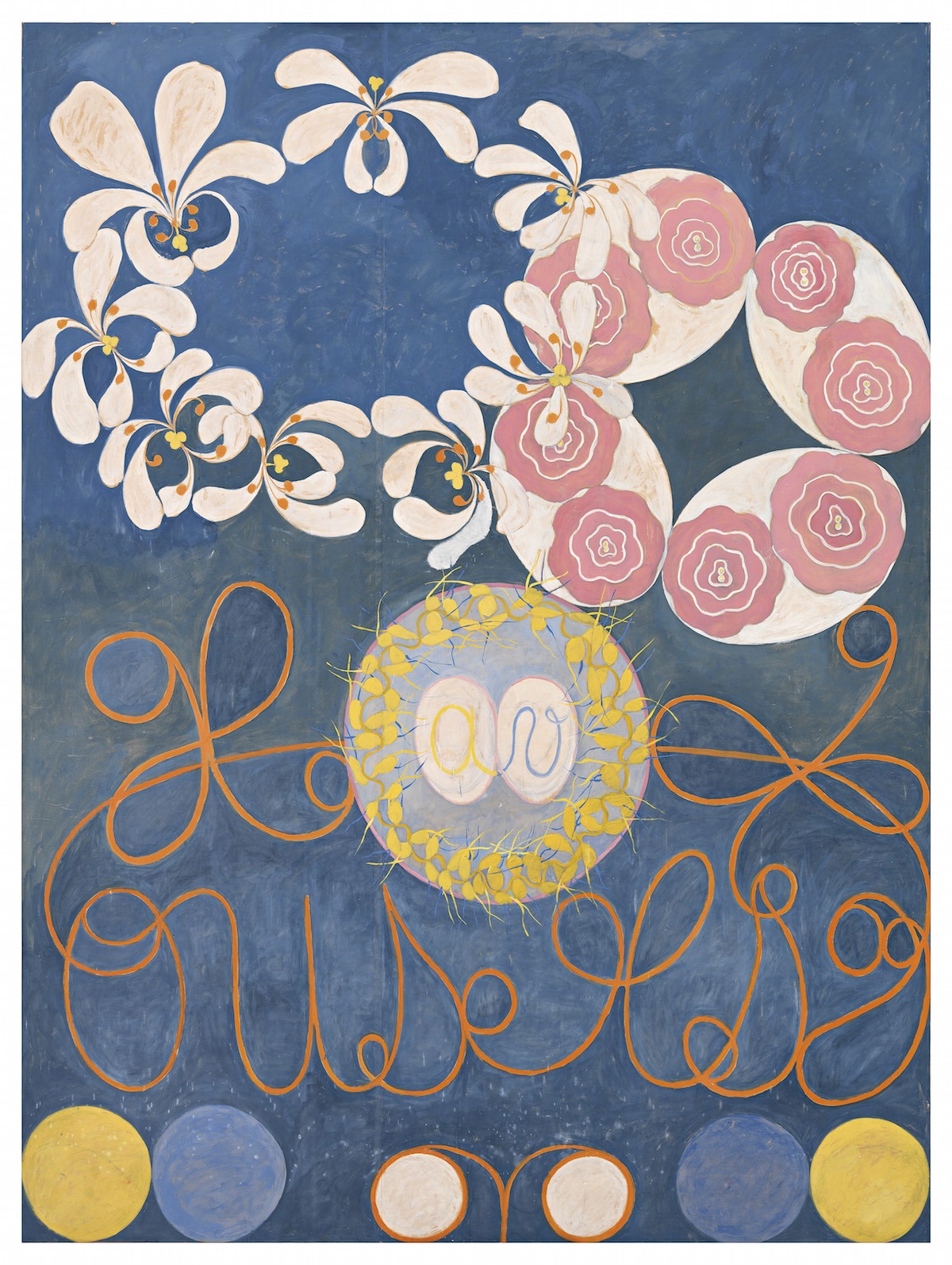

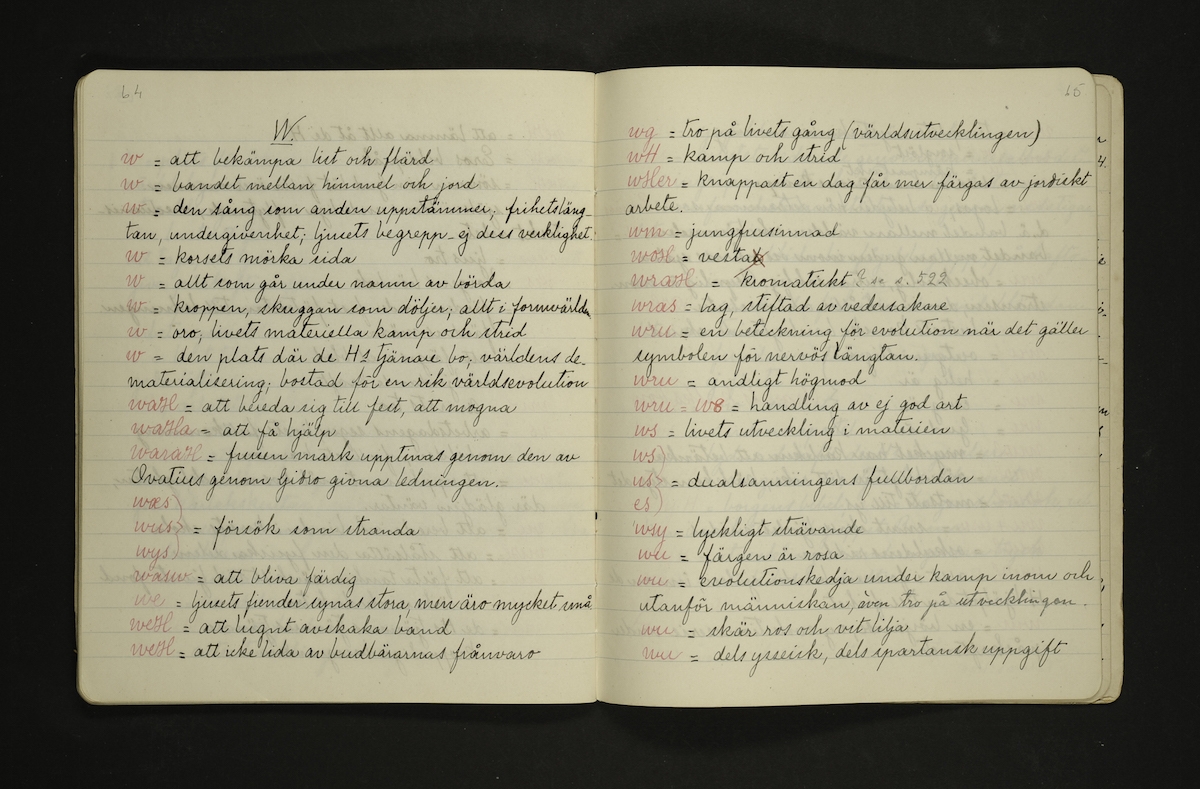

Her paintings are highly conceptual—on display was a dictionary in which the many invented words on her paintings are defined (fig. 3); every color and shape has some symbolic meaning; every symmetry is either carefully preserved or thoughtfully broken. The project of marrying the geometrical with the botanical or organic is an evident theme throughout her paintings (fig. 4). Af Klint was a spiritualist and mystic who not only belonged to the theosophical movement but saw her art as an exposition of spiritual ideas in visual language.

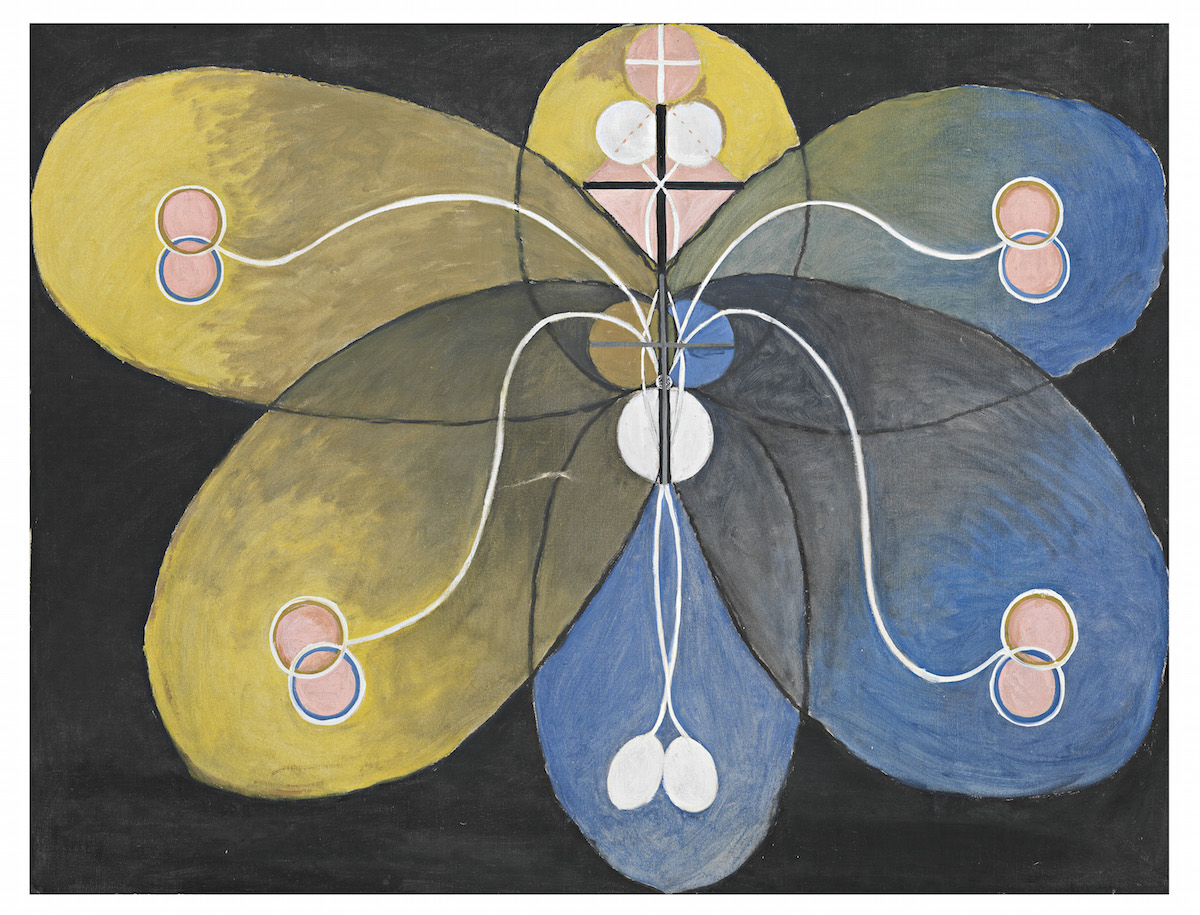

And yet, on the other hand, many of her paintings look like… my doodles. Yours too, I bet. (fig. 5, see also figs. 1 and 2) Anyone who has spent time doodling knows the way it goes: you produce lines and curves, often spirals; you blend words, flowers and geometrical shapes; your mind seems to go splat onto the page. There is something universal and unconscious about doodling; it is a visual form of free association. I marveled over how it was possible for af Klint to create art that was so doodly and free and “automatic”—and yet at the same time so controlled, schematic, plotted. How can something be at one and the same time the free play of the unconscious and a map of wacky spiritualist meaning?

When looking at her paintings, I did not feel tempted to puzzle through her cryptic taxonomies, to decode her marginalia or look up the meaning of her made-up words in the dictionary-diary. My assumption, perhaps biased and parochial, is that I won’t get much out of trying to access a bunch of bogus religious ideas. At that moment, I needed the freedom of being able to bask in colors and patterns without caring about their deeper meaning. But it wasn’t irrelevant to me that they had one.

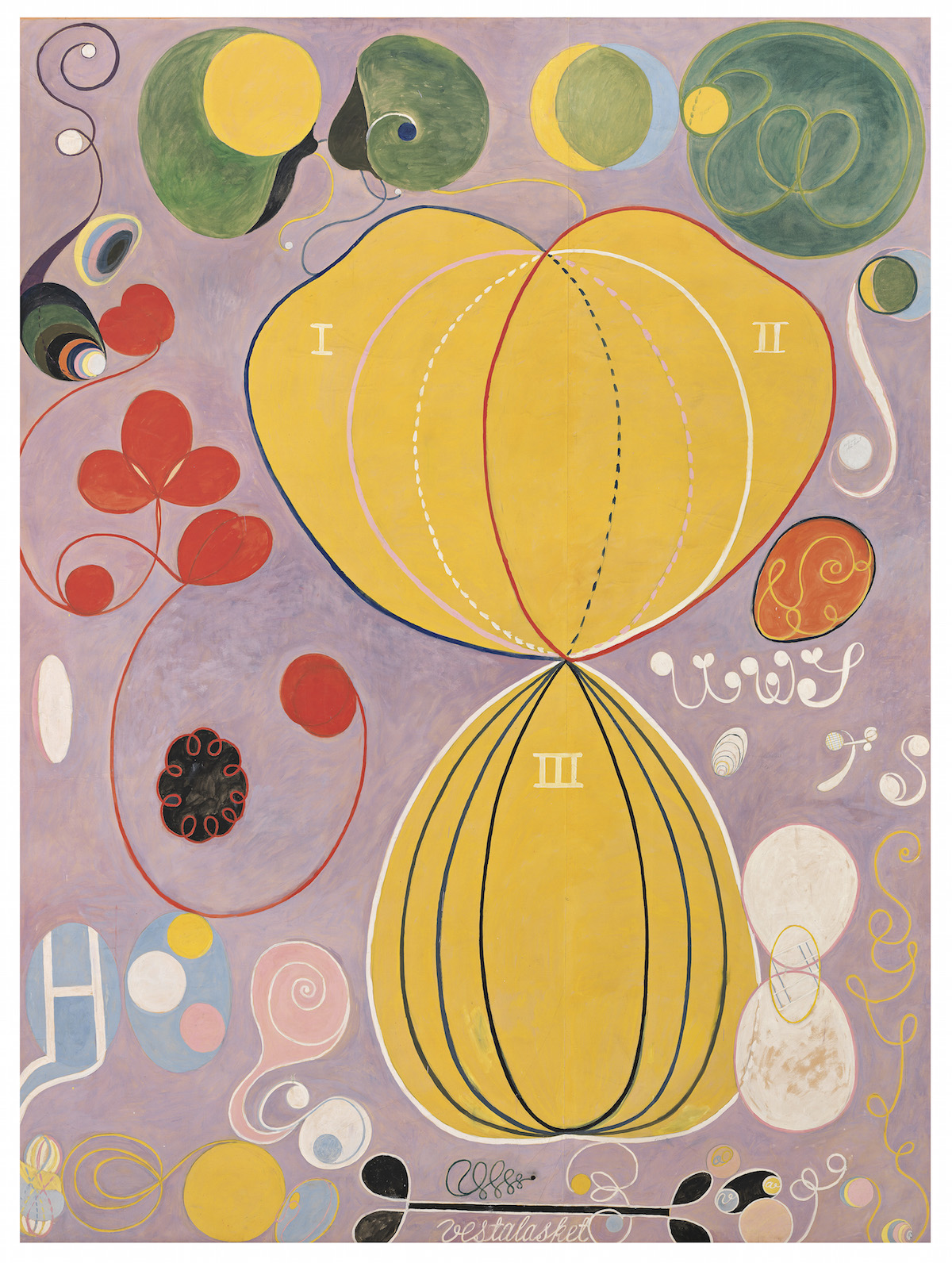

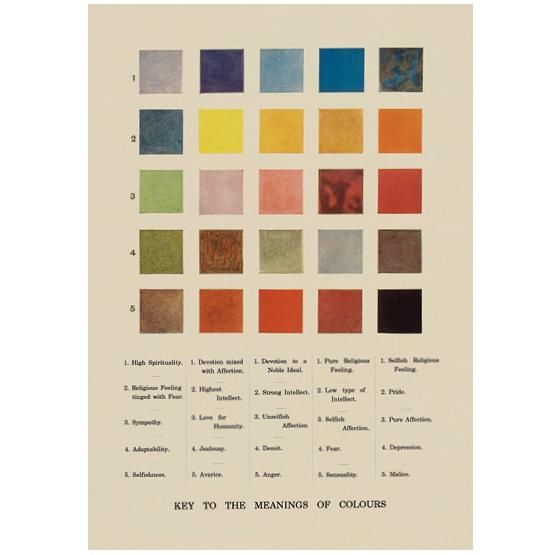

Af Klint’s color choices are amazing: the purple and yellows (fig. 5) vibrate off of one another, fixed in place as though they were not chosen at all but the products of some kind of color determinism. As, of course, they were. Af Klint did not ask herself, What colors would look good here? Which is not to say that her self-conception was that of slavish religiosity: “It was not the case that I was to blindly obey the High Lords of the Mysteries but that I was to imagine that they were always standing by my side.” Her color philosophy does not correspond precisely to others at the time, such as the one published by the London Theosophical Society (fig. 6).

She seemed to play with a variety of ideas about the meanings of colors, for instance following Goethe in rendering male as blue and female as yellow—but also using black and white to capture the same divide. Her dictionary reveals that a single word can have many different meanings. Briony Fer observes: “As an artist, af Klint was less a code-breaker than a code-maker—less a programmer of a spiritual path, more a diagrammer of fictional abstract structures and processes.” I would add that all the “help” af Klint offers the viewer—her dictionary, her notebooks—is only there to rub your confusion in your face. She doesn’t want her paintings deciphered; she knew her codes would remain unbroken.

Nonetheless, the colors are codes; they have meaning, and that matters, even when deciphering them doesn’t. The paintings grip you because they are fitted into an order in her mind, and you can intuit the existence of that order without any aspiration to inhabit it.

How often do you get to encounter a space of meaning you cannot enter? When I read a novel, I inhabit the author’s imaginative world; when I engage with a philosopher, I make his perspective my own; when I listen to music, a shared mood unites me with the musician or musicians. Af Klint holds me at arm’s length and says, “Behold me, I am a person—now stay away!” She refuses to look me in the eye, and I love it.

I have three boys, so perhaps that contributed to the fact that for me this child was, from the outset, unmistakably a “she.” A daughter, or more precisely, a nondaughter. Communing and not communing with the presently absent mind of Hilma af Klint, pondering the daughter I had and had not lost, something odd happened. In my mind, they became one single, whole person. I can’t explain it to you clearly or precisely—unthinkable thoughts don’t play by your rules. Just listen.

There was, on the one hand, this artist, long dead, whose art refused me entry, who, even if we had met, would never have seen eye to eye with me, a philosopher. I like clarity and explanations and arguments. I have no real interest in her spiritualism; she feels exactly the same scorn for my ignorance of it, as well as absolutely no need to explain herself to me. We wouldn’t have been friends.

There was, on the other hand, this maybe-wanted halfperson who would never exist. But even if she had survived past ten weeks of pregnancy, and I had not aborted her, and I had raised her, and loved her, and cared for her, she would have had to leave me to become her own full person, to develop a mind and a life of her own, much of which would take place after my death. We wouldn’t have been friends.

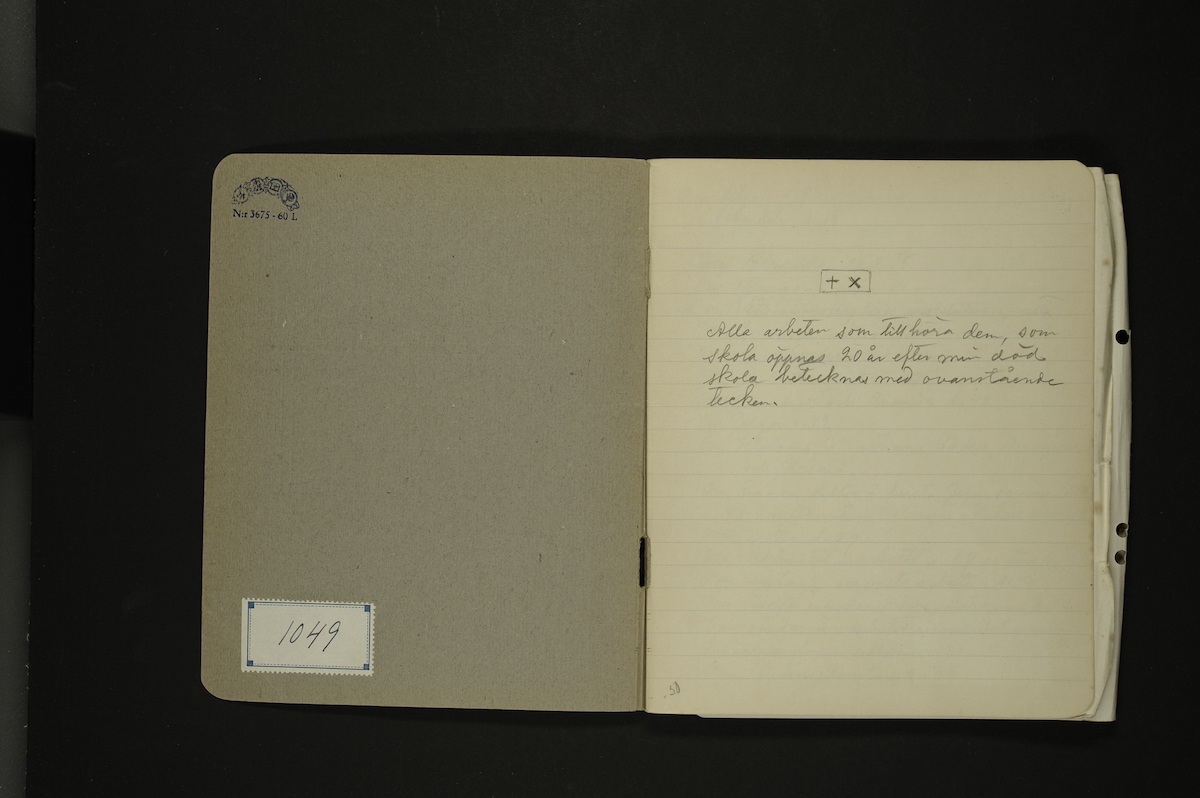

So what happened to me was this: these two presently absent beings, these nonfriends, these halfpeople, they fused together, they gave each other substance, they made the unthinkable become more thinkable. I thought about Hilma af Klint, and her symbol “+×” (fig. 7). She painted for a future she couldn’t envisage, a future filled with people she not only knew but worked to ensure would fail to access the workings of her mind.

She withheld her art from her contemporaries, and guarded it against later intruders with an array of impossible ciphers. I thought about her as existing, as present to me, and at the same time, as lost to me forever.

And I thought about the daughter I don’t have—and the sons I do. My three sons are accessible to me, I see inside their minds, I understand how their worlds work. For now. They spin around me with a delicate spiraling motion that fans just ever so slightly outward, like af Klint’s many coils and snails. Every day, their minds become more their own and less mine. My fifteen-year-old told me last night, when I expressed surprise at what he was working on, “Mama, I have a lot of irons in the fire!” Your child is a person whose mind you inhabit less and less, who will have to one day navigate a world that doesn’t include you. She is a future stranger.

●

In the days following the miscarriage, when the shock of medical urgency had passed, when I had stopped crying, when I had the peace of mind to reflect, I was able to admit to myself that what I felt was: relief. I felt like a whole person again, for the first time in months. My nausea was gone, I could climb stairs without getting out of breath, my ravenous appetite had subsided. I could think. Pregnancy clouds the mind, and life with a newborn so much more so. Giving birth to a baby is, literally, splitting in two, and it is not always clear which one your “I” goes with. Actually, it is clear. It is clearly not you. The one that matters—the real person—is the one whose needs, cries and future you spend all your time attending to. You are reduced to almost nothing, not even half a person.

After the miscarriage, I realized I had been dreading undergoing that reduction a fourth time, dreading that slow and grueling climb back up to personhood. But I didn’t know I had been dreading it until the possibility of undergoing it was gone. And that is an astonishing piece of ignorance.

So many times during the pregnancy I had asked myself: What will it feel like if I don’t have this baby? I wasn’t trying to ask myself whether I would feel guilty about the abortion, I was trying to ask myself whether I wanted the baby. Had I known that a miscarriage would bring such relief, I believe I would have had an abortion. I didn’t want to continue a pregnancy with a baby I didn’t want—even given the fact that, were I to have her, I would surely come to want and love her.

Which is not to say that, had the miscarriage not happened, I would’ve had an abortion. I think I would have carried the pregnancy to term. Because I wouldn’t have known about the relief. I couldn’t spin out the various possibilities in advance; I couldn’t look at the different futures and compare them. Sometimes one can’t do this because one lacks the imaginative and intellectual resources to simulate the different possible outcomes. In this case that was not the problem. My husband—despite the fact that he was firmly in the pro-baby camp—was not surprised by my relief about the miscarriage. If, like him, I had taken a cold, hard look at the Agnes-data, I could’ve known easily which was, at least at that time, my desired result.

But I couldn’t take that look. I couldn’t let myself simulate the two lives, one with her and one without. I couldn’t stomach that reasoning exercise. I locked the doors of my own mind, forcing myself to stand outside them. Why? Because it seemed unconscionable to play with someone’s life that way, to simulate her into nonexistence. Even half a person is more than nothing.

In December 2018, I found myself unexpectedly pregnant. I have three children, the oldest of whom is in high school, and I had not planned on negotiating the difficulties of pregnancy and early childhood at this point in my life and career. Adding a decade or so of intensive child-raising to what I’d already committed to meant curtailing my ability to achieve what I both want and need to achieve in my finite lifetime. I asked myself, what are children for?

Under those circumstances, the question takes a practical, deliberative form: should I have an abortion? I discussed my predicament with a number of people: my husband, friends, family members and even a conference room full of philosophers at the annual Eastern American Philosophical Association meeting. I discovered that people—even committed pro-choicers—cannot handle this question. A friend wrote: “I do not believe in any kind of soul, so for me there is clearly a window where ‘the A-word’ is not a moral dilemma for a woman.” Notice: he thinks there is no moral dilemma, but nonetheless he cannot bring himself to use “the A-word.”

At the philosophy conference I was one of three speakers on a panel. In the question period—this was a first for me—not a single question was directed at me. Indeed, it seemed to me as I scanned the room that the members of the audience were avoiding making eye contact with me. At the end of the session, one person came up to talk to me—not to discuss the arguments I had made, or follow up on some point needing clarification—but to assure me that she would keep what I had revealed confidential.

I think if instead of “I am considering having an abortion” I had said, “I have had an abortion” or “I am planning to have an abortion,” they could have managed the overshare much better. I would have encountered a supportive, sympathetic response, which they could have set aside to focus on the (interesting!) philosophical point about misogyny and domination that I was using my own predicament to illustrate. If I had allowed them to “read” my situation as one of ridding oneself of a clump of cells, they could have moved past the personal narrative to the philosophical problem.

Or if, instead, I had confronted them with “I have had a miscarriage”—for that is, as a matter of fact, how the pregnancy, and my deliberations about whether to continue it, would end—they would have empathized over my loss of a child. They would have been quick to concede that I had lost a baby—even though, of course, the most likely cause of a miscarriage is precisely a degree of genetic abnormality incompatible with life. From a biological point of view, “clump of cells” is a better descriptor for what is miscarried than for what, in an otherwise healthy pregnancy, is aborted.

But I doubt many women who miscarry adopt this biological point of view. My first miscarriage was two years earlier, and if I had told you about it, you could’ve responded with a less confused form of empathy than what you are probably feeling about the more recent second one. I wanted that baby, unequivocally. At barely two months pregnant I was already happily inhabiting a life in which a fourth child was coming. The miscarriage plunged me, instead, into one in which the upcoming years loomed bland, empty, shapeless. I had just been awarded tenure, and it felt like my life was over: I couldn’t see a future, couldn’t see goals, bench points, markers of meaning. My husband said that I seemed dead for a while.

Looking back on that first miscarriage, I can now see that I failed to appreciate the blessing that is unconflicted mourning. The second time around, I found myself faced with new questions: How do I mourn a child I didn’t know I wanted? A child I might, for all I knew, have been about to kill? I couldn’t make sense of my situation, I couldn’t articulate my loss as a loss or not, as cells or baby. So I am sympathetic with the audience of my APA talk, who couldn’t entertain the thought of a maybe-entity poised on the razor’s edge of cells and baby. There isn’t space for half a person. It’s an unthinkable situation.

And yet, sometimes we must think about such things nonetheless. And by “we,” I mean, first and foremost, women. Many of us become, by biological necessity, embroiled in impossible calculations involving half-people, almost humans, ghost babies.

My 2018 pregnancy didn’t last long: ten weeks, ending in January 2019. The miscarriage happened while I was traveling, in New York City. It began in the basement bathroom of the New York Public Library, where I sought refuge when I realized I wouldn’t make it to my hotel in time. There was an absolutely shocking amount of blood, and somehow it was also everywhere. All over me, all over the bathroom stall. How did it get on the door?

I thought about seeking out cleaning supplies, but the bathroom was humming and buzzing with mothers escorting children, and I couldn’t risk any of them catching a glimpse of what looked like nothing so much as a crime scene. So I had to clean the stall with only the materials inside it, which—well, you know what there is inside a women’s bathroom stall. Not much. I did my best. Then I waited for a pause in footsteps, and dashed to the sink for my Lady Macbeth moment, frantically scrubbing away at my hands so that most of the blood would be gone by the time the next person entered. How did I feel? At that time, my thoughts were mostly about blood volume (am I dying?) and location (how could I do this to the library?). I have spent many wonderful hours in the reading room upstairs, and I couldn’t help but think something like “This is no place for a miscarriage. My desecration of this sacred space is uncalled for.” I left the library and headed for my hotel room to bleed some more.

There is something distinctively miserable about sitting in a hotel room, cramping and bleeding, pretending you are “doing something” when really you are just undergoing something you don’t know how to conceptualize. I thought about my misery, and it hit me that there is something else that is difficult to conceptualize: modern art. I like it when things match, in every sense. So I put on my most blood-colored clothing and headed to the Guggenheim.

The handy thing about the Guggenheim is that there is a single-user bathroom at each full revolution. I made good use of them, to the sometime irritation of door-banging tourists speaking a variety of languages. Aside from the bathrooms, there was also the exhibition: Hilma af Klint (1862-1944), a Swedish pioneer of abstraction who worked largely in isolation from her artistic contemporaries. I suspect that few humans have had the experience I had that day: communing with an artistic visionary while miscarrying a baby you would never know whether you wanted. Let me try to communicate to you what that is like.

●

Af Klint’s art grew out of a practice of automatic drawing associated with séances, and answered to the call of High Masters whose imagined commissions guided her creations:

The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brushstroke.

Her paintings are highly conceptual—on display was a dictionary in which the many invented words on her paintings are defined (fig. 3); every color and shape has some symbolic meaning; every symmetry is either carefully preserved or thoughtfully broken. The project of marrying the geometrical with the botanical or organic is an evident theme throughout her paintings (fig. 4). Af Klint was a spiritualist and mystic who not only belonged to the theosophical movement but saw her art as an exposition of spiritual ideas in visual language.

And yet, on the other hand, many of her paintings look like… my doodles. Yours too, I bet. (fig. 5, see also figs. 1 and 2) Anyone who has spent time doodling knows the way it goes: you produce lines and curves, often spirals; you blend words, flowers and geometrical shapes; your mind seems to go splat onto the page. There is something universal and unconscious about doodling; it is a visual form of free association. I marveled over how it was possible for af Klint to create art that was so doodly and free and “automatic”—and yet at the same time so controlled, schematic, plotted. How can something be at one and the same time the free play of the unconscious and a map of wacky spiritualist meaning?

When looking at her paintings, I did not feel tempted to puzzle through her cryptic taxonomies, to decode her marginalia or look up the meaning of her made-up words in the dictionary-diary. My assumption, perhaps biased and parochial, is that I won’t get much out of trying to access a bunch of bogus religious ideas. At that moment, I needed the freedom of being able to bask in colors and patterns without caring about their deeper meaning. But it wasn’t irrelevant to me that they had one.

Af Klint’s color choices are amazing: the purple and yellows (fig. 5) vibrate off of one another, fixed in place as though they were not chosen at all but the products of some kind of color determinism. As, of course, they were. Af Klint did not ask herself, What colors would look good here? Which is not to say that her self-conception was that of slavish religiosity: “It was not the case that I was to blindly obey the High Lords of the Mysteries but that I was to imagine that they were always standing by my side.” Her color philosophy does not correspond precisely to others at the time, such as the one published by the London Theosophical Society (fig. 6).

She seemed to play with a variety of ideas about the meanings of colors, for instance following Goethe in rendering male as blue and female as yellow—but also using black and white to capture the same divide. Her dictionary reveals that a single word can have many different meanings. Briony Fer observes: “As an artist, af Klint was less a code-breaker than a code-maker—less a programmer of a spiritual path, more a diagrammer of fictional abstract structures and processes.” I would add that all the “help” af Klint offers the viewer—her dictionary, her notebooks—is only there to rub your confusion in your face. She doesn’t want her paintings deciphered; she knew her codes would remain unbroken.

Nonetheless, the colors are codes; they have meaning, and that matters, even when deciphering them doesn’t. The paintings grip you because they are fitted into an order in her mind, and you can intuit the existence of that order without any aspiration to inhabit it.

How often do you get to encounter a space of meaning you cannot enter? When I read a novel, I inhabit the author’s imaginative world; when I engage with a philosopher, I make his perspective my own; when I listen to music, a shared mood unites me with the musician or musicians. Af Klint holds me at arm’s length and says, “Behold me, I am a person—now stay away!” She refuses to look me in the eye, and I love it.

I have three boys, so perhaps that contributed to the fact that for me this child was, from the outset, unmistakably a “she.” A daughter, or more precisely, a nondaughter. Communing and not communing with the presently absent mind of Hilma af Klint, pondering the daughter I had and had not lost, something odd happened. In my mind, they became one single, whole person. I can’t explain it to you clearly or precisely—unthinkable thoughts don’t play by your rules. Just listen.

There was, on the one hand, this artist, long dead, whose art refused me entry, who, even if we had met, would never have seen eye to eye with me, a philosopher. I like clarity and explanations and arguments. I have no real interest in her spiritualism; she feels exactly the same scorn for my ignorance of it, as well as absolutely no need to explain herself to me. We wouldn’t have been friends.

There was, on the other hand, this maybe-wanted halfperson who would never exist. But even if she had survived past ten weeks of pregnancy, and I had not aborted her, and I had raised her, and loved her, and cared for her, she would have had to leave me to become her own full person, to develop a mind and a life of her own, much of which would take place after my death. We wouldn’t have been friends.

So what happened to me was this: these two presently absent beings, these nonfriends, these halfpeople, they fused together, they gave each other substance, they made the unthinkable become more thinkable. I thought about Hilma af Klint, and her symbol “+×” (fig. 7). She painted for a future she couldn’t envisage, a future filled with people she not only knew but worked to ensure would fail to access the workings of her mind.

She withheld her art from her contemporaries, and guarded it against later intruders with an array of impossible ciphers. I thought about her as existing, as present to me, and at the same time, as lost to me forever.

And I thought about the daughter I don’t have—and the sons I do. My three sons are accessible to me, I see inside their minds, I understand how their worlds work. For now. They spin around me with a delicate spiraling motion that fans just ever so slightly outward, like af Klint’s many coils and snails. Every day, their minds become more their own and less mine. My fifteen-year-old told me last night, when I expressed surprise at what he was working on, “Mama, I have a lot of irons in the fire!” Your child is a person whose mind you inhabit less and less, who will have to one day navigate a world that doesn’t include you. She is a future stranger.

●

In the days following the miscarriage, when the shock of medical urgency had passed, when I had stopped crying, when I had the peace of mind to reflect, I was able to admit to myself that what I felt was: relief. I felt like a whole person again, for the first time in months. My nausea was gone, I could climb stairs without getting out of breath, my ravenous appetite had subsided. I could think. Pregnancy clouds the mind, and life with a newborn so much more so. Giving birth to a baby is, literally, splitting in two, and it is not always clear which one your “I” goes with. Actually, it is clear. It is clearly not you. The one that matters—the real person—is the one whose needs, cries and future you spend all your time attending to. You are reduced to almost nothing, not even half a person.

After the miscarriage, I realized I had been dreading undergoing that reduction a fourth time, dreading that slow and grueling climb back up to personhood. But I didn’t know I had been dreading it until the possibility of undergoing it was gone. And that is an astonishing piece of ignorance.

So many times during the pregnancy I had asked myself: What will it feel like if I don’t have this baby? I wasn’t trying to ask myself whether I would feel guilty about the abortion, I was trying to ask myself whether I wanted the baby. Had I known that a miscarriage would bring such relief, I believe I would have had an abortion. I didn’t want to continue a pregnancy with a baby I didn’t want—even given the fact that, were I to have her, I would surely come to want and love her.

Which is not to say that, had the miscarriage not happened, I would’ve had an abortion. I think I would have carried the pregnancy to term. Because I wouldn’t have known about the relief. I couldn’t spin out the various possibilities in advance; I couldn’t look at the different futures and compare them. Sometimes one can’t do this because one lacks the imaginative and intellectual resources to simulate the different possible outcomes. In this case that was not the problem. My husband—despite the fact that he was firmly in the pro-baby camp—was not surprised by my relief about the miscarriage. If, like him, I had taken a cold, hard look at the Agnes-data, I could’ve known easily which was, at least at that time, my desired result.

But I couldn’t take that look. I couldn’t let myself simulate the two lives, one with her and one without. I couldn’t stomach that reasoning exercise. I locked the doors of my own mind, forcing myself to stand outside them. Why? Because it seemed unconscionable to play with someone’s life that way, to simulate her into nonexistence. Even half a person is more than nothing.

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.