In the summer of 2010, eighteen-year-old activist Damian Turner was shot less than three blocks from the University of Chicago hospital. Turner died in an ambulance en route to Northwestern University’s level-one adult trauma center in downtown Chicago, more than eight miles away from where he was shot. After the hospital’s leadership refused to meet with them that fall, protesters staged a “die-in” on the UofC campus, chanting, “How can you ignore, we’re dying at your door? How can you ignore, we’re bleeding on the floor? How can you ignore, we’re shot next door?”

The subsequent five years witnessed an escalation in protests over the absence of trauma care on Chicago’s South Side, which has some of the city’s highest rates of violence. Students joined local youth organizers and clergy to demand that the university assume responsibility and put resources towards funding an adult trauma-care facility at its own hospital, which is located in the approximate center of the South Side of the city. Despite increasing pressure from local politicians and elites, university leadership had for the most part remained intransigent. Yet in September 2015 the university announced that its medical center would sponsor a $40-million trauma center for adults, to be located at Holy Cross, another South Side hospital. Three months later, after continued criticism that a significant portion of the South Side would remain far from trauma care under this proposed plan, the university withdrew from the collaboration and announced that it would instead plan to provide adult trauma care on its own campus.

The intensity of demonstrations had increased in the months leading up to the first trauma center proposal this fall. Nine demonstrators—including one of the co-authors of this piece—were arrested at a sit-in at the university’s main administration building in June, and a prominent alumnus of its medical school was arrested for physically assaulting a demonstrator on campus shortly afterward. In the context of the university’s recent efforts to host Barack Obama’s presidential library, protesters succeeded in generating national media attention. Both announcements—and especially the second—underscore both the victory and efforts of years of protest.

Celebrations, however, can only be properly viewed from the historical shadow of the University of Chicago’s relationship with its African-American neighbors on the South Side. Indeed, there is little doubt that this announcement is likely to be incorporated into the university’s own narrative of innovation and its promotion of egalitarian ideals and policies. Left unexamined is how these aspirations often deny resources to the populations at the university’s borders, including many of the policies designed to desegregate the institution from within.

To be sure, the University of Chicago hardly stands out in this regard: while the Jim Crow South is often used as a foil in narratives of the broader United States as a land of opportunity, from the first Great Migration onward countless public and private institutions in northern cities have denied African-American residents social, economic and civil opportunities and rights. Even as we chart the efforts of the university to move toward racial and social inclusion internally, the parallel history of its policies toward its neighbors on the South Side requires consideration for those applauding this latest progressive victory.

●

From its inception in 1890, the University of Chicago has striven to differentiate itself from its peers on the East Coast in both social and intellectual practice. Intentionally divorcing itself from the elite American university tradition of primarily training the sons of the nation’s upper class, from day one the Chicago welcomed both women and African Americans. (Neither population would be admitted across the Ivy League in significant numbers until the late 1960s and early 1970s.) The university’s founding articles embraced notions of equality remarkable for the late nineteenth century, including the promise to “provide, impart, and furnish opportunities for all departments of higher education to persons of both sexes on equal terms.”

Over the course of the twentieth century the University of Chicago trained and supported a number of renowned African-American students. Horace Cayton and St. Claire Drake, the co-authors of Black Metropolis (1945), were both doctoral students in sociology at the university in the 1930s. The anthropologist Allison Davis, the first African-American faculty member granted tenure at any major white institution, gained this position at Chicago.

But the university’s internal commitments to racial inclusion would not extend to its relationship with the African-American population redlined at Hyde Park’s borders, just a couple miles away from Chicago’s “Black Belt,” until the Supreme Court banned racially restrictive covenants in 1948. As Richard Wright writes in his novel Native Son, for the South Side’s black population the university was just “the school out there on the Midway.”

The stark distance between Black Chicago and the University suggested by Wright’s “out there” is not unidirectional: “out there”—with all the connotations of fear, phobia, and wilderness that it may bear—also captures the university’s stance toward its black neighbors, irrespective of its racially progressive agenda on campus.

And “out there” also captures how difficult, if not impossible, Chicago’s African-American population have found it to access the school’s resources, whether that was for education, a medical emergency, or both. In his introduction to Cayton and Drake’s Black Metropolis, Wright noted that living in the vicinity of the University of Chicago had given him his “first concrete vision of the forces that molded the urban Negro’s body and soul.” This vision was not gained through acceptance. “I was never a student at the university,” Wright continued. “It is doubtful if I could have passed the entrance examination.”

Perhaps Wright was unqualified for the “Great Books” curriculum implemented at the university from the late 1920s, but for African Americans and Jews especially, rarely were matters of admission divorced from racial anxieties before World War II. Even though, as a black man, Allison Davis would eventually gain admittance to the university’s private faculty club in 1948, he was still unable to secure housing in Hyde Park. (Three years earlier, seventeen employees walked out in protest after Davis’s application to the club was defeated by a vote of 182 to 85, which became a national news story.) Even Robert Hutchins, the university president who was convinced to advocate for Davis’s professorship by the Rosenwald Fund after its director offered to pay the first three years of Davis’s salary, remained noncommittal—and through the 1940s, publicly hostile—to the “problem of our property on the South Side.” Failing to reconcile the university’s commitment to nondiscrimination in academic affairs and its extensive engagements with racially segregated housing, Hutchins conceded, “I think they are different. But don’t ask me why.”

For students, the university’s off-campus residential housing would remain segregated until the early 1960s. (In 1962, Bernie Sanders led a campaign of black and white students protesting the university’s policy of owning a number of segregated buildings, the university’s first civil rights sit-in.) Often this segregation was directed, funded, or operated in tandem with what Black Metropolis described as so-called “neighborhood improvement associations.” The book quotes a report published in Hyde Park’s neighborhood newspaper in 1928, which proclaimed the efficacy of these organizations. The paper would hail the area as protected by a “fine network of contracts that like a marvelous delicately woven chain of armor is being raised from the northern gates of Hyde Park at 35th Street and Drexel Boulevard to Woodlawn, Park Manor, South Shore, Windsor Park and all the far-flung white communities of the South Side.”

Before he assumed co-ownership of the project that would become Black Metropolis, Horace Cayton had protested the fact that the university, where he was then a graduate student, was receiving funding from the federal government as part of the WPA Program to study the black community on the South Side. Cayton sent a letter to WPA administrators lambasting the university for supporting residential segregation that exacerbated African Americans’ reliance on the predominantly overcrowded and dilapidated housing beyond Hyde Park’s borders. The university, he wrote, “oozes a constant secretion of racial prejudice and intolerance.” As evidence of the university’s refusal to recognize its contribution to structural inequality, he pointed to its medical school, which refused to allow its students of color to intern in fear of protests from white patients.

●

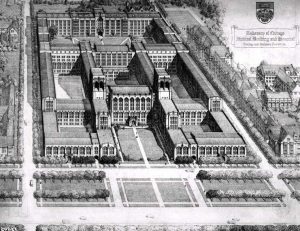

As Cayton would have certainly been aware, the medical center at the University of Chicago was bound by Jim Crow-styled segregation before it even existed. In 1916 the businessman and prominent philanthropist Julius Rosenwald was approached to fund the modern medical facility. It would be his gift that inspired a number of Chicago’s philanthropic families to follow suit in donating funds for the university hospital, which would not open until 1927. Because of the success of the university hospital and comparable developments at hospitals elsewhere in the city, by the 1950s the city of Chicago would be widely considered “the medical center of the world.”Rosenwald boasted that it was a “rare privilege to be associated in so noble a service for not only the people of our home City but for the ‘life of the whole nation,’ as one friend put it.”

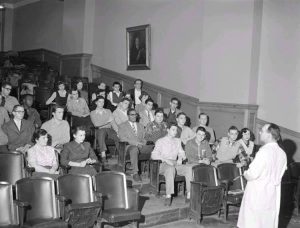

But the fruits of Rosenwald’s gift would also inadvertently highlight the racial boundaries and limitations of the university’s new medical facility. In 1937, The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP, reported that letters had been sent to “each member of the [Illinois] state legislature calling his attention to the Jim Crow practices” at Northwestern, the University of Illinois and the University of Chicago, noting that “the University of Chicago has large tax-exempt properties including a new and extensive medical center which discriminates against Negro citizens and Negro students.” It would continue to be difficult for the university to maintain the nondiscriminatory racial policies it championed in the school’s academic practices more broadly when it came to its hospital. In its graduating class of 1968, the University of Chicago had only one black medical student.

Recognizing what the University of Chicago’s new medical facility would not accomplish, in 1929 Rosenwald spearheaded the process of raising funds to open a “Medical Center for Negroes” at another hospital on Chicago’s South Side. On January 14, 1930, in cooperation with the University of Chicago, Provident, one of the nation’s first hospitals for African Americans, publicly announced a $3-million campaign to reorganize its hospital. Because the University of Chicago did not allow its black medical students to train at its own facilities, and consistently denied treatment to black Chicagoans (including its own students), its plan to finance, educate and provide medical care for African Americans at Provident was initially considered a winning compromise. The sponsorship and proposal were praised in news reports and trade publications across the country, and in 1930 The Crisis would report that the joint initiative had been “hailed as the most significant interracial movement in recent years.”

By 1933, the university could report down to the penny on the progress of its collaboration with Provident, boasting in its own magazine that appropriations for the project totaled $4,341,102.63 “for Negro medical education, in which is included one million dollars to the University of Chicago for endowment of instruction in the Provident Hospital.” But funding and support for the proposed medical center at Provident would evaporate quickly, and Provident would still be seeking additional resources to adequately develop its own medical center through the 1940s. By 1935, The Crisis would report that the “Jim Crow alliance of Provident Hospital and the Medical School of the University of Chicago” had been “condemned and protest filed” with the trustees of both institutions.

●

None of this should imply that the University of Chicago is a static institution, or that social conditions on Chicago’s South Side have not changed. But the university’s struggle to achieve some measure of racial justice in the early 1930s, soon after developing its own racially exclusive medical center, resonates for good reason with its more recent history of intransigence in response to protests for a trauma center, especially its first plan, which—intentionally or not—could easily be read as an attempt to keep trauma care off its own campus.

This recent history should also not be confused with conscious racial prejudice. Like almost all of the United States, the University of Chicago has, in its hospital and on campus, long ago abandoned explicitly racial criteria in favor of the ruling ideology of colorblindness. Even at mid-century, and despite displays of explicitly segregationist ideology, there were no George Wallaces standing in the door of the university to make an official stand against integration. But racial inequality does not need explicit enforcement in order to persist: in this case it is maintained partly by the legacy of legally sanctioned discrimination and partly by the retrenchment of social welfare over the last forty years. And the university’s consistent deference to the reigning racial ideology of the day is suggestive of the broader failure of Chicago—which remains the most segregated major city in the country—in particular and of the United States in general to overcome a history of racial inequality.

For the university to truly challenge hegemonic racial ideologies, instead of offering the occasional concession to its neighbors, would mean relinquishing its position as a local site of power in two ways. On the one hand it would mean breaking with, or at the very least openly challenging, the city’s political establishment, with which it has continued to enjoy a close relationship. On the other it would mean sharing not only resources but also a voice in their distribution with the university’s black neighbors. To those who have claimed (correctly or not; time will tell) that it would be financially impossible for the university to become the primary provider of social services to the South Side, the answer might be to ask the following: Should the institution not then openly challenge the withdrawal of public services from its neighborhood?

In a late-Nineties speech criticizing the expansion of the university’s private police force on the South Side, Danielle Allen, the institution’s first African-American dean, said that “to share resources in mutually beneficial ways is only half of the business of political friendship. It is crucial to remember that even generous citizens will be distrusted if they refuse to share power.” Allen bolstered this argument by reminding her audience, the faculty senate, about the university’s movement at the end of the twentieth century to “treat trust-building as central to the reversal of the boundaries exploited in the 1950s and 1960s.” The mid-century programs of “urban renewal” to which Allen was referring are a key chapter in the history of the university’s role in the making and unmaking of Black Chicago. Once legal segregation was off the table, “slum clearance” and “neighborhood improvement” became mechanisms by which the university could ensure “controlled integration.” These developments have also enabled the University to strengthen its position on the South Side, and to reflect what became widely accepted by many Americans as a robust, colorblind social order. Needless to say, such efforts generated little more trust from the South Side’s African-American population than the earlier, explicitly segregationist regime.

More recently, and despite the recent positive outcome of the half-decade campaign for a trauma center, there has been little in the way of increased trust between the university and its African-American neighbors. Perhaps it is fair to say, then, that the university now, as it has for eight decades, excels in setting social and intellectual precedents within its own academic and professional community, but only experiments with like-minded commitments to the city’s other residents under pressure.

An article like this can only be written in the aftermath of a long and contentious campaign of protest, which, unlike many others, was unambiguously successful—at least for now. But the historical problem that we are suggesting is most clearly seen not only in the fact that the campaign for a trauma center took half a decade, not only that it required no less than three separate series of arrests, not only, even, that it required protest as such to achieve an essential (albeit ultimately modest, given the current state of health care in America) improvement in the distribution of trauma care. The logic of “in here” and “out there,” which Wright recognized as the way the university and the South Side were held together, remains largely intact. The American racial order (of which the two versions of “out there” alluded to in Native Son are an expression) has, for the last century or so, found one of its most potent sites on Chicago’s South Side. This order is of neither the University of Chicago’s making nor its choosing. But it has its consent.

Image credits: Protest photos by Luke White; historical images courtesy of the University of Chicago Library

In the summer of 2010, eighteen-year-old activist Damian Turner was shot less than three blocks from the University of Chicago hospital. Turner died in an ambulance en route to Northwestern University’s level-one adult trauma center in downtown Chicago, more than eight miles away from where he was shot. After the hospital’s leadership refused to meet with them that fall, protesters staged a “die-in” on the UofC campus, chanting, “How can you ignore, we’re dying at your door? How can you ignore, we’re bleeding on the floor? How can you ignore, we’re shot next door?”

The subsequent five years witnessed an escalation in protests over the absence of trauma care on Chicago’s South Side, which has some of the city’s highest rates of violence. Students joined local youth organizers and clergy to demand that the university assume responsibility and put resources towards funding an adult trauma-care facility at its own hospital, which is located in the approximate center of the South Side of the city. Despite increasing pressure from local politicians and elites, university leadership had for the most part remained intransigent. Yet in September 2015 the university announced that its medical center would sponsor a $40-million trauma center for adults, to be located at Holy Cross, another South Side hospital. Three months later, after continued criticism that a significant portion of the South Side would remain far from trauma care under this proposed plan, the university withdrew from the collaboration and announced that it would instead plan to provide adult trauma care on its own campus.

The intensity of demonstrations had increased in the months leading up to the first trauma center proposal this fall. Nine demonstrators—including one of the co-authors of this piece—were arrested at a sit-in at the university’s main administration building in June, and a prominent alumnus of its medical school was arrested for physically assaulting a demonstrator on campus shortly afterward. In the context of the university’s recent efforts to host Barack Obama’s presidential library, protesters succeeded in generating national media attention. Both announcements—and especially the second—underscore both the victory and efforts of years of protest.

Celebrations, however, can only be properly viewed from the historical shadow of the University of Chicago’s relationship with its African-American neighbors on the South Side. Indeed, there is little doubt that this announcement is likely to be incorporated into the university’s own narrative of innovation and its promotion of egalitarian ideals and policies. Left unexamined is how these aspirations often deny resources to the populations at the university’s borders, including many of the policies designed to desegregate the institution from within.

To be sure, the University of Chicago hardly stands out in this regard: while the Jim Crow South is often used as a foil in narratives of the broader United States as a land of opportunity, from the first Great Migration onward countless public and private institutions in northern cities have denied African-American residents social, economic and civil opportunities and rights. Even as we chart the efforts of the university to move toward racial and social inclusion internally, the parallel history of its policies toward its neighbors on the South Side requires consideration for those applauding this latest progressive victory.

●

From its inception in 1890, the University of Chicago has striven to differentiate itself from its peers on the East Coast in both social and intellectual practice. Intentionally divorcing itself from the elite American university tradition of primarily training the sons of the nation’s upper class, from day one the Chicago welcomed both women and African Americans. (Neither population would be admitted across the Ivy League in significant numbers until the late 1960s and early 1970s.) The university’s founding articles embraced notions of equality remarkable for the late nineteenth century, including the promise to “provide, impart, and furnish opportunities for all departments of higher education to persons of both sexes on equal terms.”

Over the course of the twentieth century the University of Chicago trained and supported a number of renowned African-American students. Horace Cayton and St. Claire Drake, the co-authors of Black Metropolis (1945), were both doctoral students in sociology at the university in the 1930s. The anthropologist Allison Davis, the first African-American faculty member granted tenure at any major white institution, gained this position at Chicago.

But the university’s internal commitments to racial inclusion would not extend to its relationship with the African-American population redlined at Hyde Park’s borders, just a couple miles away from Chicago’s “Black Belt,” until the Supreme Court banned racially restrictive covenants in 1948. As Richard Wright writes in his novel Native Son, for the South Side’s black population the university was just “the school out there on the Midway.”

The stark distance between Black Chicago and the University suggested by Wright’s “out there” is not unidirectional: “out there”—with all the connotations of fear, phobia, and wilderness that it may bear—also captures the university’s stance toward its black neighbors, irrespective of its racially progressive agenda on campus.

And “out there” also captures how difficult, if not impossible, Chicago’s African-American population have found it to access the school’s resources, whether that was for education, a medical emergency, or both. In his introduction to Cayton and Drake’s Black Metropolis, Wright noted that living in the vicinity of the University of Chicago had given him his “first concrete vision of the forces that molded the urban Negro’s body and soul.” This vision was not gained through acceptance. “I was never a student at the university,” Wright continued. “It is doubtful if I could have passed the entrance examination.”

Perhaps Wright was unqualified for the “Great Books” curriculum implemented at the university from the late 1920s, but for African Americans and Jews especially, rarely were matters of admission divorced from racial anxieties before World War II. Even though, as a black man, Allison Davis would eventually gain admittance to the university’s private faculty club in 1948, he was still unable to secure housing in Hyde Park. (Three years earlier, seventeen employees walked out in protest after Davis’s application to the club was defeated by a vote of 182 to 85, which became a national news story.) Even Robert Hutchins, the university president who was convinced to advocate for Davis’s professorship by the Rosenwald Fund after its director offered to pay the first three years of Davis’s salary, remained noncommittal—and through the 1940s, publicly hostile—to the “problem of our property on the South Side.” Failing to reconcile the university’s commitment to nondiscrimination in academic affairs and its extensive engagements with racially segregated housing, Hutchins conceded, “I think they are different. But don’t ask me why.”

For students, the university’s off-campus residential housing would remain segregated until the early 1960s. (In 1962, Bernie Sanders led a campaign of black and white students protesting the university’s policy of owning a number of segregated buildings, the university’s first civil rights sit-in.) Often this segregation was directed, funded, or operated in tandem with what Black Metropolis described as so-called “neighborhood improvement associations.” The book quotes a report published in Hyde Park’s neighborhood newspaper in 1928, which proclaimed the efficacy of these organizations. The paper would hail the area as protected by a “fine network of contracts that like a marvelous delicately woven chain of armor is being raised from the northern gates of Hyde Park at 35th Street and Drexel Boulevard to Woodlawn, Park Manor, South Shore, Windsor Park and all the far-flung white communities of the South Side.”

Before he assumed co-ownership of the project that would become Black Metropolis, Horace Cayton had protested the fact that the university, where he was then a graduate student, was receiving funding from the federal government as part of the WPA Program to study the black community on the South Side. Cayton sent a letter to WPA administrators lambasting the university for supporting residential segregation that exacerbated African Americans’ reliance on the predominantly overcrowded and dilapidated housing beyond Hyde Park’s borders. The university, he wrote, “oozes a constant secretion of racial prejudice and intolerance.” As evidence of the university’s refusal to recognize its contribution to structural inequality, he pointed to its medical school, which refused to allow its students of color to intern in fear of protests from white patients.

●

As Cayton would have certainly been aware, the medical center at the University of Chicago was bound by Jim Crow-styled segregation before it even existed. In 1916 the businessman and prominent philanthropist Julius Rosenwald was approached to fund the modern medical facility. It would be his gift that inspired a number of Chicago’s philanthropic families to follow suit in donating funds for the university hospital, which would not open until 1927. Because of the success of the university hospital and comparable developments at hospitals elsewhere in the city, by the 1950s the city of Chicago would be widely considered “the medical center of the world.”Rosenwald boasted that it was a “rare privilege to be associated in so noble a service for not only the people of our home City but for the ‘life of the whole nation,’ as one friend put it.”

But the fruits of Rosenwald’s gift would also inadvertently highlight the racial boundaries and limitations of the university’s new medical facility. In 1937, The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP, reported that letters had been sent to “each member of the [Illinois] state legislature calling his attention to the Jim Crow practices” at Northwestern, the University of Illinois and the University of Chicago, noting that “the University of Chicago has large tax-exempt properties including a new and extensive medical center which discriminates against Negro citizens and Negro students.” It would continue to be difficult for the university to maintain the nondiscriminatory racial policies it championed in the school’s academic practices more broadly when it came to its hospital. In its graduating class of 1968, the University of Chicago had only one black medical student.

Recognizing what the University of Chicago’s new medical facility would not accomplish, in 1929 Rosenwald spearheaded the process of raising funds to open a “Medical Center for Negroes” at another hospital on Chicago’s South Side. On January 14, 1930, in cooperation with the University of Chicago, Provident, one of the nation’s first hospitals for African Americans, publicly announced a $3-million campaign to reorganize its hospital. Because the University of Chicago did not allow its black medical students to train at its own facilities, and consistently denied treatment to black Chicagoans (including its own students), its plan to finance, educate and provide medical care for African Americans at Provident was initially considered a winning compromise. The sponsorship and proposal were praised in news reports and trade publications across the country, and in 1930 The Crisis would report that the joint initiative had been “hailed as the most significant interracial movement in recent years.”

By 1933, the university could report down to the penny on the progress of its collaboration with Provident, boasting in its own magazine that appropriations for the project totaled $4,341,102.63 “for Negro medical education, in which is included one million dollars to the University of Chicago for endowment of instruction in the Provident Hospital.” But funding and support for the proposed medical center at Provident would evaporate quickly, and Provident would still be seeking additional resources to adequately develop its own medical center through the 1940s. By 1935, The Crisis would report that the “Jim Crow alliance of Provident Hospital and the Medical School of the University of Chicago” had been “condemned and protest filed” with the trustees of both institutions.

●

None of this should imply that the University of Chicago is a static institution, or that social conditions on Chicago’s South Side have not changed. But the university’s struggle to achieve some measure of racial justice in the early 1930s, soon after developing its own racially exclusive medical center, resonates for good reason with its more recent history of intransigence in response to protests for a trauma center, especially its first plan, which—intentionally or not—could easily be read as an attempt to keep trauma care off its own campus.

This recent history should also not be confused with conscious racial prejudice. Like almost all of the United States, the University of Chicago has, in its hospital and on campus, long ago abandoned explicitly racial criteria in favor of the ruling ideology of colorblindness. Even at mid-century, and despite displays of explicitly segregationist ideology, there were no George Wallaces standing in the door of the university to make an official stand against integration. But racial inequality does not need explicit enforcement in order to persist: in this case it is maintained partly by the legacy of legally sanctioned discrimination and partly by the retrenchment of social welfare over the last forty years. And the university’s consistent deference to the reigning racial ideology of the day is suggestive of the broader failure of Chicago—which remains the most segregated major city in the country—in particular and of the United States in general to overcome a history of racial inequality.

For the university to truly challenge hegemonic racial ideologies, instead of offering the occasional concession to its neighbors, would mean relinquishing its position as a local site of power in two ways. On the one hand it would mean breaking with, or at the very least openly challenging, the city’s political establishment, with which it has continued to enjoy a close relationship. On the other it would mean sharing not only resources but also a voice in their distribution with the university’s black neighbors. To those who have claimed (correctly or not; time will tell) that it would be financially impossible for the university to become the primary provider of social services to the South Side, the answer might be to ask the following: Should the institution not then openly challenge the withdrawal of public services from its neighborhood?

In a late-Nineties speech criticizing the expansion of the university’s private police force on the South Side, Danielle Allen, the institution’s first African-American dean, said that “to share resources in mutually beneficial ways is only half of the business of political friendship. It is crucial to remember that even generous citizens will be distrusted if they refuse to share power.” Allen bolstered this argument by reminding her audience, the faculty senate, about the university’s movement at the end of the twentieth century to “treat trust-building as central to the reversal of the boundaries exploited in the 1950s and 1960s.” The mid-century programs of “urban renewal” to which Allen was referring are a key chapter in the history of the university’s role in the making and unmaking of Black Chicago. Once legal segregation was off the table, “slum clearance” and “neighborhood improvement” became mechanisms by which the university could ensure “controlled integration.” These developments have also enabled the University to strengthen its position on the South Side, and to reflect what became widely accepted by many Americans as a robust, colorblind social order. Needless to say, such efforts generated little more trust from the South Side’s African-American population than the earlier, explicitly segregationist regime.

More recently, and despite the recent positive outcome of the half-decade campaign for a trauma center, there has been little in the way of increased trust between the university and its African-American neighbors. Perhaps it is fair to say, then, that the university now, as it has for eight decades, excels in setting social and intellectual precedents within its own academic and professional community, but only experiments with like-minded commitments to the city’s other residents under pressure.

An article like this can only be written in the aftermath of a long and contentious campaign of protest, which, unlike many others, was unambiguously successful—at least for now. But the historical problem that we are suggesting is most clearly seen not only in the fact that the campaign for a trauma center took half a decade, not only that it required no less than three separate series of arrests, not only, even, that it required protest as such to achieve an essential (albeit ultimately modest, given the current state of health care in America) improvement in the distribution of trauma care. The logic of “in here” and “out there,” which Wright recognized as the way the university and the South Side were held together, remains largely intact. The American racial order (of which the two versions of “out there” alluded to in Native Son are an expression) has, for the last century or so, found one of its most potent sites on Chicago’s South Side. This order is of neither the University of Chicago’s making nor its choosing. But it has its consent.

Image credits: Protest photos by Luke White; historical images courtesy of the University of Chicago Library

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.