Three days on, it feels like an abyss has opened up. I thought I knew something, I thought I understood the world, and I didn’t. I was cautious thinking about strategy when I should have been bold; I was bold in predicting the future when I should have been cautious. All my hopes were false and, worst of all, all of my suspicions were true. I trusted polls, I trusted experts, I trusted insiders. I should have trusted my instinct as a son of exiles and grandson of refugees. I’ve spent half my life studying history and politics, and I feel as if it hasn’t taught me anything.

Social science assumes that a pattern governs human affairs. I think all we have is a wheel of fire. I’ve started to think that all history gives us is stories, stories that accumulate meaning like springs and burst through at the appointed time. For the past few years I’ve been keeping a file of the stories that speak to me on notecards in my desk. Some are about madness, some are about ambition. Some are about paradise. Some are about hell. Some are about victory. Some are about defeat.

Today I’ve mostly been looking at the ones about defeat. As I was trying to wrap my head around what has happened, and thinking about the responsibility of artists and intellectuals in a new world, I thought about calamity, I thought about catastrophe, I thought about retreat, I thought about surrender. I reached into my folder and this story leapt out at me from my files. It comes from thirteenth-century China, and concerns the last days of the Southern Song dynasty.

The barbarians arrived many years before. They moved slowly, grabbing one part of the country, then another. China was a vast realm, and they could not swallow it whole.

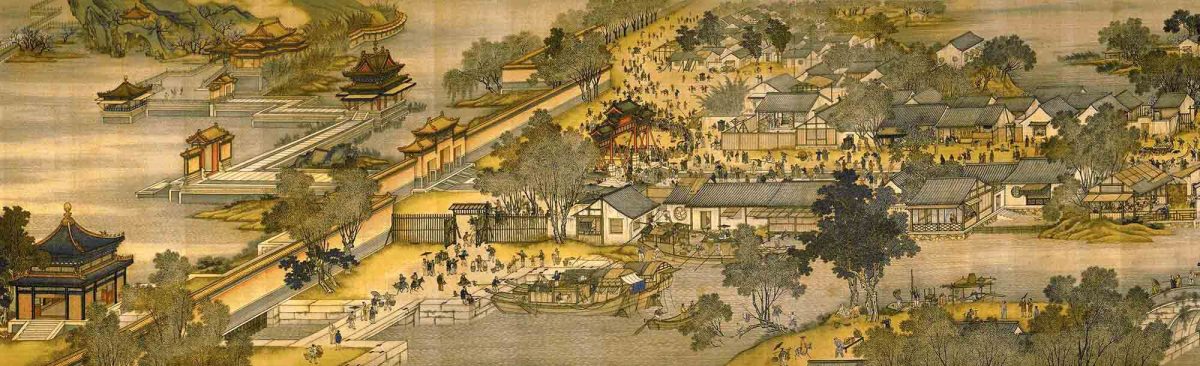

The rulers of the dynasty did not worry too much. They moved their capital far to the south. It was a beautiful city, built alongside a lake surrounded by villas and restaurants. Its many tea houses and brothels were all famous for their excellence. Its university was ancient and renowned. The city was a paradise of amusements for the literati who ran the kingdom and hosted its countless salons.

In the capital, the arts flourished. Painting was especially prized, but only that done by amateurs. To make paintings for money was considered impossibly vulgar. The profession of painter was no better than that of butcher.

The mountains and monasteries that surrounded the lake lent themselves particularly well to painting of landscapes. A favorite subject was the intellectual in his robes, staring into the waters of a stream. Distant vistas gained in melancholy and nostalgia from the diligent application of mist.

Everything the literati did was exquisite and refined. They enjoyed the pleasures afforded by revelry as well as those that came from tranquility. They loved to debate civic duty and poetic form. For one hundred and fifty years they enjoyed the calm of their southern bastion.

But finally, the day came when the barbarians arrived in front of the walls. The men of the kingdom were not warriors. They were more acquainted with the zither and chessboard than the use of arms. Still, they were certain of victory. They had the best weapons, the most ingenious defenses, the most learned men.

The barbarians had only numbers, patience and time.

On the day of battle, it rained. An ill wind struck the dynasty’s fleet. Bodies filled the waters like fibers of hemp. Ministers and high officials watched from the deck of a ship. Seeing the disaster unfold, they chose to plunge into the water rather than suffer defeat. Clutched in the arms of his chief councillor and tied down by weights of gold, the emperor, a child of seven, joined them. The remaining literati returned to their homes and slit their own throats.

One survivor was captured. Passing north in chains, he saw the tomb of a dissident from another time. It was crowned with the words “grave of a man without a ruler.” He begged his captors for death. Four years passed before they granted his wish.

Not everything perished with the arrival of the barbarians, though. Some admired the paintings they found in the palaces they looted and added them to their collections. Soon, the cold cities of the north were warmed by scenes of scholars playing chess, listening to music and practicing calligraphy.

Fashion is fleeting, however. With time, the barbarians came to prefer an art of their own. It showed the things dearest to their hearts. Horses. Men at arms. Soldiers on the field of battle, scattered in a rout.

●

What to do about the barbarians? I see that question being asked everywhere right now, in so many words. Some counsel empathy. Some argue pragmatism and some demand resistance. Some even see them as a kind of opportunity.

I think of the great poem by C. P. Cavafy which begins with the citizens of a city gathered in the forum, waiting for the barbarians to arrive, and ends with them disappointed when they don’t, asking “And now, what’s going to happen to us without barbarians? / They were, those people, a kind of solution.”

There are some who view what happened on Tuesday as just that kind of solution: a cleansing fire, which will bring the left back to something authentic and pure. A mass party, with mass appeal. I wish I shared that enthusiasm. I wish I could believe that there was someone out there to convince.

●

In 2004, I was a teacher in a Moroccan high school. One of the courses I taught was in American history. The night of the election I wept in shame. The next day in class I read Whitman aloud with my students, not because I love his poetry, but because he represents the America I love best: open, embracing, home to multitudes.

Today I feel fear.

I keep re-reading Zbigniew Herbert’s poem “The Longobards.” It begins with the barbarians crouched in the Alps, ready to enter Italy with their whips. It ends like this:

An immense coldness from the Longobards

Their shadow sears the grass when they descend into the valley

Shouting their protracted n o t h i n g n o t h i n g n o t h i n g

Three days on, it feels like an abyss has opened up. I thought I knew something, I thought I understood the world, and I didn’t. I was cautious thinking about strategy when I should have been bold; I was bold in predicting the future when I should have been cautious. All my hopes were false and, worst of all, all of my suspicions were true. I trusted polls, I trusted experts, I trusted insiders. I should have trusted my instinct as a son of exiles and grandson of refugees. I’ve spent half my life studying history and politics, and I feel as if it hasn’t taught me anything.

Social science assumes that a pattern governs human affairs. I think all we have is a wheel of fire. I’ve started to think that all history gives us is stories, stories that accumulate meaning like springs and burst through at the appointed time. For the past few years I’ve been keeping a file of the stories that speak to me on notecards in my desk. Some are about madness, some are about ambition. Some are about paradise. Some are about hell. Some are about victory. Some are about defeat.

Today I’ve mostly been looking at the ones about defeat. As I was trying to wrap my head around what has happened, and thinking about the responsibility of artists and intellectuals in a new world, I thought about calamity, I thought about catastrophe, I thought about retreat, I thought about surrender. I reached into my folder and this story leapt out at me from my files. It comes from thirteenth-century China, and concerns the last days of the Southern Song dynasty.

The barbarians arrived many years before. They moved slowly, grabbing one part of the country, then another. China was a vast realm, and they could not swallow it whole.

The rulers of the dynasty did not worry too much. They moved their capital far to the south. It was a beautiful city, built alongside a lake surrounded by villas and restaurants. Its many tea houses and brothels were all famous for their excellence. Its university was ancient and renowned. The city was a paradise of amusements for the literati who ran the kingdom and hosted its countless salons.

In the capital, the arts flourished. Painting was especially prized, but only that done by amateurs. To make paintings for money was considered impossibly vulgar. The profession of painter was no better than that of butcher.

The mountains and monasteries that surrounded the lake lent themselves particularly well to painting of landscapes. A favorite subject was the intellectual in his robes, staring into the waters of a stream. Distant vistas gained in melancholy and nostalgia from the diligent application of mist.

Everything the literati did was exquisite and refined. They enjoyed the pleasures afforded by revelry as well as those that came from tranquility. They loved to debate civic duty and poetic form. For one hundred and fifty years they enjoyed the calm of their southern bastion.

But finally, the day came when the barbarians arrived in front of the walls. The men of the kingdom were not warriors. They were more acquainted with the zither and chessboard than the use of arms. Still, they were certain of victory. They had the best weapons, the most ingenious defenses, the most learned men.

The barbarians had only numbers, patience and time.

On the day of battle, it rained. An ill wind struck the dynasty’s fleet. Bodies filled the waters like fibers of hemp. Ministers and high officials watched from the deck of a ship. Seeing the disaster unfold, they chose to plunge into the water rather than suffer defeat. Clutched in the arms of his chief councillor and tied down by weights of gold, the emperor, a child of seven, joined them. The remaining literati returned to their homes and slit their own throats.

One survivor was captured. Passing north in chains, he saw the tomb of a dissident from another time. It was crowned with the words “grave of a man without a ruler.” He begged his captors for death. Four years passed before they granted his wish.

Not everything perished with the arrival of the barbarians, though. Some admired the paintings they found in the palaces they looted and added them to their collections. Soon, the cold cities of the north were warmed by scenes of scholars playing chess, listening to music and practicing calligraphy.

Fashion is fleeting, however. With time, the barbarians came to prefer an art of their own. It showed the things dearest to their hearts. Horses. Men at arms. Soldiers on the field of battle, scattered in a rout.

●

What to do about the barbarians? I see that question being asked everywhere right now, in so many words. Some counsel empathy. Some argue pragmatism and some demand resistance. Some even see them as a kind of opportunity.

I think of the great poem by C. P. Cavafy which begins with the citizens of a city gathered in the forum, waiting for the barbarians to arrive, and ends with them disappointed when they don’t, asking “And now, what’s going to happen to us without barbarians? / They were, those people, a kind of solution.”

There are some who view what happened on Tuesday as just that kind of solution: a cleansing fire, which will bring the left back to something authentic and pure. A mass party, with mass appeal. I wish I shared that enthusiasm. I wish I could believe that there was someone out there to convince.

●

In 2004, I was a teacher in a Moroccan high school. One of the courses I taught was in American history. The night of the election I wept in shame. The next day in class I read Whitman aloud with my students, not because I love his poetry, but because he represents the America I love best: open, embracing, home to multitudes.

Today I feel fear.

I keep re-reading Zbigniew Herbert’s poem “The Longobards.” It begins with the barbarians crouched in the Alps, ready to enter Italy with their whips. It ends like this:

An immense coldness from the Longobards

Their shadow sears the grass when they descend into the valley

Shouting their protracted n o t h i n g n o t h i n g n o t h i n g

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.