Last November, Kanye West stopped by Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design to deliver a three-minute manifesto on the state of architecture today. Standing atop a drafting table in the middle of the school’s cavernous design studio, impeccably turned out in a white bomber jacket and faux construction boots, Kanye issued a series of proclamations on creativity unbound. “I really do believe that the world can be saved through design and everything can be architected,” he announced to his cheering audience. “I believe,” he continued, “that utopia is actually possible—but we’re led by the least noble, the least dignified, the least tasteful, the dumbest and the most political.” In a world cluttered by artistic and intellectual detritus, the architect’s studio emerged as one of the only free spaces for utopian thought. Here the imagination could run wild, unbridled by such constraints as money, politics, bad taste and the desires of other human beings. For Kanye, the fantasy of total self-creation was nothing short of revolutionary. He concluded on an uncharacteristically humble note: “I’m very inspired to be in this space.”

Say what you will about Kanye West’s edifice complex, but he’s not the first person to suggest that we can build our way to “utopia”—a term as imprecise as it is overused in architectural theory. When Kanye talks about utopia, he is not holding up a generally “virtuous” or “just” way of building, à la utopia’s master theorists like Plato or Sir Thomas More. Rather, Kanye is pulling from an overstuffed grab bag of design principles that have served as the keystones of the twentieth century’s major architectural movements. The futuristic pavilions of communism dreamed up by the Soviet Union’s constructivist architects in the 1920s and 1930s were pitched as everyday utopian spaces for the masses. The rational modernism of the 1940s and 1950s claimed as utopian those buildings that reflected the material conditions of mid-century industrialism—single-family homes made entirely of steel and glass and reinforced concrete, like Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye or Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House. Even the fragmented follies of Bernard Tschumi’s Parc de la Villette in 1982 were presented as a postmodern utopia, the ideal reflection of how late capitalism had resulted in total spatial disintegration. For much of the last century, then, laying claim to utopia, in theory and in practice, was the most compelling strategy for announcing a new direction in design.

But since the 1980s, we have seen a decoupling of utopian language, however vague or slipshod it may seem, from actual building practices. In no small part, this is due to the rise of commercial “starchitects” like Norman Foster and Frank Gehry, happy to recycle last year’s designs for billionaire developers who are, in turn, happy to look the other way as creativity grinds to a halt. Bored by what commercial design has to offer, utopian thought and experimental design have retreated to the academy. There it keeps company with theoretical architects like Tschumi, John Hejduk and Peter Eisenman, who rose to prominence in the 1980s and 1990s only to be pushed to the margins of commercial practice. These “paper architects” of the avant-garde—so called because they work exclusively in the medium of drawing—are the last holdouts of a creative impulse that has lost its way to the real world. So the question remains: After the schism of building in theory and building in practice, what hope is there for a reunion of imagination and concrete?

Kanye thinks he has the answer. So does Bjarke Ingels, the architecture world’s own enfant terrible and rising starchitect of the moment. Some will recognize Ingels as the heir apparent to Rem Koolhaas, founder of OMA and arguably the most controversial architect of the last thirty years—not to mention one of Kanye’s recent design collaborators. Others may recall Ingels from the lengthy profile that appeared in the New Yorker late last year, just as he was preparing to break ground on his first project in New York City: a slick white pyramid that will soon slice through W. 57th St., known around town simply as “W57.” But several years before he became a household name in New York, Ingels’s Copenhagen-based practice, Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), wrote and il-lustrated Yes Is More, a 400-page comic book that BIG marketed as a “manifesto of pop culture.” In it, Ingels and his team use BIG’s designs to make the case for architecture as a practice of “pragmatic utopianism”—a utopia that is actually possible—while loudly championing Ingels as the master architect of our future.

Ingels peddles a utopia of total creative control. Yes Is More imagines cities in which perfectly identical buildings can be stacked on top of one another like Legoland sets, encouraging city blocks skyward, one module at a time. It transforms quiet waterfronts into “super-harbors” that teem with shipping containers and trade traffic; we can imagine how the logos of DONDA—Kanye’s newly established design practice—or BIG might bask proudly in the sunlight that shines off the water. In Yes Is More, residences, offices and shopping malls proudly merge in urban monoliths with names like “Bureaucratic Beauty” or “Infinity Loop”—a hard-to-miss suggestion that these buildings are designed to ensure that every aspect of public and private life is lived in “total compliance” with the architect’s vision of the future. This is the twisted fantasy whose popular diffusion links W. 57th St. to Kanye West, and utopia to the depersonalized designs that are currently infiltrating our cities.

While Ingels’s design aesthetic lacks space for even the most basic varieties of humanity, his turn to the comic book form with Yes Is More is nevertheless telling. For one, the architect’s foray into the world of comics shows us why the comic form is so well suited for thinking about—and drawing—utopia. As John McMorrough writes in his introduction to Chicago-area architect Jimenez Lai’s graphic novel Citizens of No Place, comic book artists use space to create “pocket universes where possibility is unregulated by the weight of history or, in some cases, even the weight of gravity.” (Lai takes this directive quite literally by designing a utopian spaceship that bears an uncanny resemblance to the luxury cruise liner from Pixar’s WALL-E.) Like Kanye’s fantasy of the architect’s studio, the comic can offer a narrative supplement to real buildings—a different form of “paper architecture,” keenly attuned to the construction of new, experimental worlds.

But if the comic form can illuminate the experimental possibilities of architecture, it can just as easily expose its limitations, throwing into relief the shallowness of a design concept, say, or its sloppy articulation. In making the impossible banal, Yes Is More falls prey to precisely this kind of self-exposure. The comic’s heavy lines and bright colors exacerbate Ingels’s penchant for flatness, yielding cartoon structures so dense and impenetrable that they stop the imagination. The speech and thought bubbles that allow Ingels to narrate BIG’s triumph over unsuspecting landscapes and funding impasses contain language best reserved for the comic-book villain. “We architects don’t have to remain misunderstood geniuses, frustrated by the lack of understanding, appreciation or funding,” he announces in the manifesto’s opening pages. In reading Yes Is More, one thinks not of Rem Koolhaas’s manifesto Delirious New York but of graphic novelist Chip Kidd’s Batman: Death by Design, which casts as Batman’s nemesis a preening architect named Kem Roomhaus, hell-bent on transforming Gotham City according to his garishly outsize tastes. Big is bad for mankind.

Despite the expansive arrogance of Yes Is More, there is something playful and compelling about the idea that comics can breathe new life into contemporary architecture. What if we flipped the relationship between architecture and the comic on its head? What if we asked how professional comic artists have chosen to visualize the future of architectural design? Where the architect’s imagination has floundered, works of comic art like David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp and Chris Ware’s Building Stories have emerged as superior examples of paper architecture, buoyed by similar questions about how we inhabit space. Where the architectural comic has gone big in order to grapple with its utopian impulses, comic art has gone small. By small, we don’t mean diminutive in stature or modest in ambition. Rather, the small and supple worlds of comic art feature built spaces we can navigate and construct with our hands, bringing us one step closer to the experience of touching—and feeling intimately in touch with—our dwellings.

●

At the crossroads of architecture and the comic is Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp, the love story of architecture professor Asterios Polyp—an unwieldy, snobbish, weak-chinned scrap of a man—and his lovely wife Hana. Asterios is one of the paper architects of the 1980s and 1990s avant-garde, a tight-knit coterie of poststructuralist designers who took their cues directly from French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s understanding of architecture as a form of writing. Like Derrida’s one-time collaborator Peter Eisenman, Asterios’s reputation rests on “his designs, rather than on the buildings constructed from them.” Nothing he has designed has ever been built. Rather, his career is an accumulation of riddles, abstractions and analogues, systems and sequences “governed by their own internal logic.” They take little by way of inspiration from the material world and give next to nothing back. Asterios Polyp, we could conclude, is the story of a man who could have authored a savvier version of Yes Is More.

Mazzucchelli draws Asterios as an extension of his intellectual sensibilities, a not-so-subtle takedown of architectural theory that’s delightful to behold in comic form. At his most pedantic moments—lecturing a class on Apollonian versus Dionysian design, or boasting about his sexual prowess at a faculty meeting—Asterios’s body morphs into an artist’s mannequin, a cool blue assemblage of hollow geometries that bear no relationship to the world around him. Meeting Hana for the first time, his form fills out. She is all warmth and feeling, a shy sculptor who enters Asterios’s life in hundreds of delicate pink brushstrokes, like one of Toulouse-Lautrec’s barstool muses but with infinitely less self-assurance. Hana makes messy and inviting sculptures out of found objects. She reveres the imperfect shapes of half-plucked daisies and pine cones and knitting loops; her medium is garbage. When she and Asterios meet, their coupling is the stuff of myth—Aristophanes’s long-lost soul mates completing each other, aesthetically and emotionally.

But like most mythic couples, their love falls prey to hubris. After all, Asterios was the birth name of the Minotaur, an unlovable monster trapped by Daedalus’s labyrinthine take on a simple design problem. Asterios does not see how the idea of utopia—in design and, by extension, in love—can hem in the imagination until there’s room left for only one person’s construction of the rules of art and life. Asterios’s narcissism, we are meant to believe, is intimately connected to his inflexible aesthetic beliefs—“the certitude of symmetry, the consonance of counterpoise” and the “eloquent equilibriums” that inspire his impossible-to-build designs. He holds on to these beliefs at great cost. Hana divorces him fiercely and suddenly, leaving Asterios to grieve in a labyrinth of his own making.

Like most tragic heroes, Asterios is given the chance to redeem himself. After a fire destroys his New York apartment, Asterios takes a despairing bus ride into the heart of Middle America—the East Coast academic’s descent into the underworld. There, in a small town named Apogee, he finds a job as a car repairman, working for a burly auto mechanic named Stiff Major and living with Stiff’s family, his clairvoyant wife Ursula Major and their son Jackson. Stripped of his pretensions and worldly possessions—the Breuer chairs, the van der Rohe lounge—Asterios begins to build. Out of a pile of reclaimed wood, he and Stiff decide to make a tree house for Jackson. “I’m no Frank Lord Wright,” Stiff claims as he thrusts a crumpled piece of paper at Asterios, “but I made a little sketch.”

Ironically, it does look a little like one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s houses, a modest tip of the hat to Fallingwater and its intimate rapport with nature. Nestled in the treetops, its roof cantilevering out over the boughs, the tree house is Asterios’s first construction, a collaborative effort between Stiff’s design and Asterios’s own two hands. Mazzucchelli pays special attention to these hands when drawing the construction process. We see them palming the planks as if to test their firmness; we see jolts of energy—normally reserved for the comic book’s “ZAP!” “BAM!” or “POW!” moments—that connect the hammer in Asterios’s left hand to the nail in his right; we see the sinuous tensing in his forearms as he grips at the rope that binds the planks to the tree, reuniting the discarded wood with the nature whence it came. From building comes a different way of being and—literally—of being in touch with the world, one that trades the siren song of utopia for the smaller delights of handicraft. Only now can Asterios return to Hana, armed with an appreciation for working together to build something that endures. Only now can she forgive him.

From Asterios Polyp, we could go back to architectural theory—to Martin Heidegger, author of the slim and intractable essay “Building Dwelling Thinking,” which considers the world-making powers of built space; or Emmanuel Petit, who in a recent issue of Log celebrates the possibility of a sensual, even organismic closeness between people and interiors. But it is more illuminating to connect the devotional handicraft of Asterios Polyp to architects who have paid homage to the human hand in practice, like Pierre Chareau, William Morris, or, more recently, Tom Kundig. Chareau’s most famous commission, the Maison de Verre, may seem more sophisticated than Asterios’s tree house—it was once the preferred meeting place of Walter Benjamin and Jean Cocteau in Paris—but its design honors similar principles. Every corner is nimbly packed with gadgets and gizmos: spinning gears, rotating levers, extendable hinges and pivoting surfaces whose kinetic essence encourages or even demands their obsessive use. Here the hand is key. By touching, turning, pressing and pulling on skylights and walls, one can alter the parts of the house that are crucial to its design, thereby participating in its authorship. Far removed from the architect of utopia, who lords over an unreal city, the shared human touch is what makes building—and buildings—desirable, now and into the ever-shifting future.

●

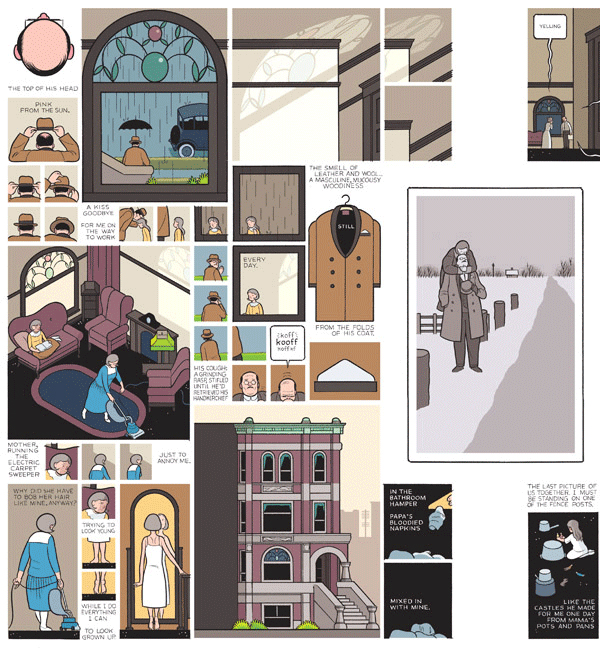

Perhaps no recent work of comic art has enjoyed as much praise from readers and illustrators alike as Chris Ware’s Building Stories. Reviewing it, Daniel Worden speaks of Ware’s architectural “nostalgia for an earlier industrial era,” and compares the Chicago brownstone that sits at the center of Building Stories to “a ruin”—an “aesthetic object” that elicits “melancholy” for the irrecoverable past. Indeed, Ware’s tale of an unnamed woman overcome by depression, anxiety, self-doubt and ennui sprawls masterfully across fourteen pieces of text—a handful of books both large and small, newspaper pullouts, pamphlets, even a board game. It also covers nearly one hundred years in the life of a Humboldt Park brownstone, one that has succumbed to the kind of shabby gentility that precedes demolition. But for most readers, unused to spending this much time with a building, poring over the thousands of angles from which Ware has chosen to draw it, Building Stories exudes an immediacy that the ruin denies. Like Asterios Polyp, it extends the promise of shared creation: by touching and turning and arranging the pieces of Building Stories, you can build your own story, inhabit your own intimately knowable and narrateable world.

Ware has claimed that architecture is “the aesthetic key to the development of the cartoons as an art form.” (Ware’s notebooks and sketches from the past two decades are chock-full of statements like this.) But we could just as easily flip his observation, and claim that Building Stories’ intimate sense of touch unlocks radical ways of sensing buildings—as conscious, powerful and motivated; buildings as not merely aesthetic objects, but subjects unto themselves. In Building Stories, the building narrates its own history in a fusty, cursive hand that trails in and out of its rooms like an absentminded great-aunt, pausing here and there to run a finger over a pair of dusty end tables and reminisce. “It relied on the memory of tenants to stay alive,” the building thinks of itself, as it sheds a shingle to mourn the memories of tenants past:

It particularly preferred the company of the younger women—(They usually did such tasteful things with the place, kept it clean…)

Plus the pink pitter-patter of freshly showered feet, tickling its joints… that was always nice.

Actually, there were a number of good memories… What was her name? She liked to roll around on the floor…

Or this one… a bit fat, but she had friendly fingers and a warm rump…

Or her—the way she’d open a door; gently grasp, twist, and pull… oh!

Buried in these recollections is a serious provocation: If you tickle us, do we not laugh? Where it once seemed impossible for fiction to imagine the inner states of human beings dissimilar to us, Ware dares us to embody the consciousness of something nonhuman and, in doing so, to consider our incommensurable senses of touch. If you were a building, what would it feel like to have your joints tickled? Your knobs twisted? How might you experience the weight and warmth of the human body, its cleanliness and color? Is this building’s lingering “oh!” a cry of pleasure or pain or something else entirely? Is it a sensation that we cannot reroute by way of our all-too-human metaphors?

We could interpret Ware’s provocation to imagine how a building feels on its own terms as radically severing Building Stories from the human point of view. But Ware’s building is never entirely separate from the consciousness of the building’s third-floor tenant, the unnamed woman who lost her left leg in a motorboat accident. Pink-cheeked, a little dowdy, depression-prone and unshakably lonely, she is most often seen hobbling from room to room, wondering what to do with her life. Over time, her body and thoughts seem to map the building’s interior spaces. “Having spent an unusual amount of my childhood sitting on the floor,” she writes in her diary, “I became more than a little acquainted with the world of baseboards, doorstops and electrical plugs, to say nothing of all the valves and faucets that hide behind toilets and sinks.” In a moment that recalls Chareau’s house of gadgets, she confronts an overflowing toilet with her crutch—an extension of her body—plugging it into the toilet’s fill valve to stop the water from running. “I was sort of proud of myself for figuring this out,” she confesses, “You just don’t realize how much you take things for granted until they’re taken away … how interdependent the ‘modern’ world is.” It is the interdependence between humans and buildings—the fusion of the tactile with the tectonic—that provides the woman a rare break from her numb resignation. No matter how sad or small this connectivity might seem, it is one of the only ways for her to be and to feel in relation to the world.

Today the house of fiction is full of such “alien phenomenologies,” to borrow a term from critic and graphic designer Ian Bogost. But Ware suggests that they are largely absent from the esteemed buildings of American architecture, whose imaginative possibilities seem foreclosed by their iconicity. In one of Building Stories’ newspaper-sized pamphlets, Ware airlifts his readers from Humboldt Park to Oak Park, the leafy suburb that is home to many of Frank Lloyd Wright’s early homes, including the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio. (Built in 1889 with a loan from his employer Louis Sullivan, the Wright Home effectively launched the career that would dwarf Sullivan’s own by the next decade.) A century later, Ware’s unnamed woman walks down the streets of Oak Park huffing at the Wright Home’s status as a mere “tourist attraction.” Against the vibrant greens of springtime, there it sits, a flat and uninviting slab of art. “Sometimes I really hate it here,” the woman thinks as she pushes past the horde of gawping German tourists who clog the sidewalk. The tourists need to be reminded that “people still live and work” around these parts, but it’s not entirely their fault. In becoming iconic and therefore uninhabitable, the Wright House has forsaken its contact with the life of the imagination. It can no longer offer the kinds of in-touch experiences that the brownstone delights in. (We could say the same of any contemporary architect who aims to fix an icon, rather than create a space for dwelling.)

For Ware, there is a radical and touching interdependence between humans and things, designers and dwellers, form and everyday function. “Not to brag, but we buildings are able to—how might you say it—grope our way around the future a bit,” the brownstone announces, groping its way to a prophecy: its lonely tenant will marry a young architect whom she meets at a friend’s party and invites up to her apartment one evening in an act of unprecedented bravery, leaving the building vacant and alone. Eventually the bulldozers and wrecking balls will come for it. But it will not be gone—at least, not entirely. In what could be considered one of the strangest panels in Building Stories, Ware flashes forward 150 years to a man and a woman standing where the building had once stood, their heads encased by a virtual interface that is busy pulling “memory fragments” from “this area’s consciousness cloud.” As they read the building’s memories, visualizing its inhabitants and recording their feelings, the woman reflects on the self-centeredness that once obscured from human beings the truth about our existence. “People really did think they were just single particles back then,” she observes in disbelief.

Against the ego and narcissism of big utopia, against its desire for absolute control, the paper architecture of graphic novels gives us a simple alternative: let us grope our way into the interdependent future—one small, delightful touch at a time.

Last November, Kanye West stopped by Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design to deliver a three-minute manifesto on the state of architecture today. Standing atop a drafting table in the middle of the school’s cavernous design studio, impeccably turned out in a white bomber jacket and faux construction boots, Kanye issued a series of proclamations on creativity unbound. “I really do believe that the world can be saved through design and everything can be architected,” he announced to his cheering audience. “I believe,” he continued, “that utopia is actually possible—but we’re led by the least noble, the least dignified, the least tasteful, the dumbest and the most political.” In a world cluttered by artistic and intellectual detritus, the architect’s studio emerged as one of the only free spaces for utopian thought. Here the imagination could run wild, unbridled by such constraints as money, politics, bad taste and the desires of other human beings. For Kanye, the fantasy of total self-creation was nothing short of revolutionary. He concluded on an uncharacteristically humble note: “I’m very inspired to be in this space.”

Say what you will about Kanye West’s edifice complex, but he’s not the first person to suggest that we can build our way to “utopia”—a term as imprecise as it is overused in architectural theory. When Kanye talks about utopia, he is not holding up a generally “virtuous” or “just” way of building, à la utopia’s master theorists like Plato or Sir Thomas More. Rather, Kanye is pulling from an overstuffed grab bag of design principles that have served as the keystones of the twentieth century’s major architectural movements. The futuristic pavilions of communism dreamed up by the Soviet Union’s constructivist architects in the 1920s and 1930s were pitched as everyday utopian spaces for the masses. The rational modernism of the 1940s and 1950s claimed as utopian those buildings that reflected the material conditions of mid-century industrialism—single-family homes made entirely of steel and glass and reinforced concrete, like Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye or Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House. Even the fragmented follies of Bernard Tschumi’s Parc de la Villette in 1982 were presented as a postmodern utopia, the ideal reflection of how late capitalism had resulted in total spatial disintegration. For much of the last century, then, laying claim to utopia, in theory and in practice, was the most compelling strategy for announcing a new direction in design.

But since the 1980s, we have seen a decoupling of utopian language, however vague or slipshod it may seem, from actual building practices. In no small part, this is due to the rise of commercial “starchitects” like Norman Foster and Frank Gehry, happy to recycle last year’s designs for billionaire developers who are, in turn, happy to look the other way as creativity grinds to a halt. Bored by what commercial design has to offer, utopian thought and experimental design have retreated to the academy. There it keeps company with theoretical architects like Tschumi, John Hejduk and Peter Eisenman, who rose to prominence in the 1980s and 1990s only to be pushed to the margins of commercial practice. These “paper architects” of the avant-garde—so called because they work exclusively in the medium of drawing—are the last holdouts of a creative impulse that has lost its way to the real world. So the question remains: After the schism of building in theory and building in practice, what hope is there for a reunion of imagination and concrete?

Kanye thinks he has the answer. So does Bjarke Ingels, the architecture world’s own enfant terrible and rising starchitect of the moment. Some will recognize Ingels as the heir apparent to Rem Koolhaas, founder of OMA and arguably the most controversial architect of the last thirty years—not to mention one of Kanye’s recent design collaborators. Others may recall Ingels from the lengthy profile that appeared in the New Yorker late last year, just as he was preparing to break ground on his first project in New York City: a slick white pyramid that will soon slice through W. 57th St., known around town simply as “W57.” But several years before he became a household name in New York, Ingels’s Copenhagen-based practice, Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), wrote and il-lustrated Yes Is More, a 400-page comic book that BIG marketed as a “manifesto of pop culture.” In it, Ingels and his team use BIG’s designs to make the case for architecture as a practice of “pragmatic utopianism”—a utopia that is actually possible—while loudly championing Ingels as the master architect of our future.

Ingels peddles a utopia of total creative control. Yes Is More imagines cities in which perfectly identical buildings can be stacked on top of one another like Legoland sets, encouraging city blocks skyward, one module at a time. It transforms quiet waterfronts into “super-harbors” that teem with shipping containers and trade traffic; we can imagine how the logos of DONDA—Kanye’s newly established design practice—or BIG might bask proudly in the sunlight that shines off the water. In Yes Is More, residences, offices and shopping malls proudly merge in urban monoliths with names like “Bureaucratic Beauty” or “Infinity Loop”—a hard-to-miss suggestion that these buildings are designed to ensure that every aspect of public and private life is lived in “total compliance” with the architect’s vision of the future. This is the twisted fantasy whose popular diffusion links W. 57th St. to Kanye West, and utopia to the depersonalized designs that are currently infiltrating our cities.

While Ingels’s design aesthetic lacks space for even the most basic varieties of humanity, his turn to the comic book form with Yes Is More is nevertheless telling. For one, the architect’s foray into the world of comics shows us why the comic form is so well suited for thinking about—and drawing—utopia. As John McMorrough writes in his introduction to Chicago-area architect Jimenez Lai’s graphic novel Citizens of No Place, comic book artists use space to create “pocket universes where possibility is unregulated by the weight of history or, in some cases, even the weight of gravity.” (Lai takes this directive quite literally by designing a utopian spaceship that bears an uncanny resemblance to the luxury cruise liner from Pixar’s WALL-E.) Like Kanye’s fantasy of the architect’s studio, the comic can offer a narrative supplement to real buildings—a different form of “paper architecture,” keenly attuned to the construction of new, experimental worlds.

But if the comic form can illuminate the experimental possibilities of architecture, it can just as easily expose its limitations, throwing into relief the shallowness of a design concept, say, or its sloppy articulation. In making the impossible banal, Yes Is More falls prey to precisely this kind of self-exposure. The comic’s heavy lines and bright colors exacerbate Ingels’s penchant for flatness, yielding cartoon structures so dense and impenetrable that they stop the imagination. The speech and thought bubbles that allow Ingels to narrate BIG’s triumph over unsuspecting landscapes and funding impasses contain language best reserved for the comic-book villain. “We architects don’t have to remain misunderstood geniuses, frustrated by the lack of understanding, appreciation or funding,” he announces in the manifesto’s opening pages. In reading Yes Is More, one thinks not of Rem Koolhaas’s manifesto Delirious New York but of graphic novelist Chip Kidd’s Batman: Death by Design, which casts as Batman’s nemesis a preening architect named Kem Roomhaus, hell-bent on transforming Gotham City according to his garishly outsize tastes. Big is bad for mankind.

Despite the expansive arrogance of Yes Is More, there is something playful and compelling about the idea that comics can breathe new life into contemporary architecture. What if we flipped the relationship between architecture and the comic on its head? What if we asked how professional comic artists have chosen to visualize the future of architectural design? Where the architect’s imagination has floundered, works of comic art like David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp and Chris Ware’s Building Stories have emerged as superior examples of paper architecture, buoyed by similar questions about how we inhabit space. Where the architectural comic has gone big in order to grapple with its utopian impulses, comic art has gone small. By small, we don’t mean diminutive in stature or modest in ambition. Rather, the small and supple worlds of comic art feature built spaces we can navigate and construct with our hands, bringing us one step closer to the experience of touching—and feeling intimately in touch with—our dwellings.

●

At the crossroads of architecture and the comic is Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp, the love story of architecture professor Asterios Polyp—an unwieldy, snobbish, weak-chinned scrap of a man—and his lovely wife Hana. Asterios is one of the paper architects of the 1980s and 1990s avant-garde, a tight-knit coterie of poststructuralist designers who took their cues directly from French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s understanding of architecture as a form of writing. Like Derrida’s one-time collaborator Peter Eisenman, Asterios’s reputation rests on “his designs, rather than on the buildings constructed from them.” Nothing he has designed has ever been built. Rather, his career is an accumulation of riddles, abstractions and analogues, systems and sequences “governed by their own internal logic.” They take little by way of inspiration from the material world and give next to nothing back. Asterios Polyp, we could conclude, is the story of a man who could have authored a savvier version of Yes Is More.

Mazzucchelli draws Asterios as an extension of his intellectual sensibilities, a not-so-subtle takedown of architectural theory that’s delightful to behold in comic form. At his most pedantic moments—lecturing a class on Apollonian versus Dionysian design, or boasting about his sexual prowess at a faculty meeting—Asterios’s body morphs into an artist’s mannequin, a cool blue assemblage of hollow geometries that bear no relationship to the world around him. Meeting Hana for the first time, his form fills out. She is all warmth and feeling, a shy sculptor who enters Asterios’s life in hundreds of delicate pink brushstrokes, like one of Toulouse-Lautrec’s barstool muses but with infinitely less self-assurance. Hana makes messy and inviting sculptures out of found objects. She reveres the imperfect shapes of half-plucked daisies and pine cones and knitting loops; her medium is garbage. When she and Asterios meet, their coupling is the stuff of myth—Aristophanes’s long-lost soul mates completing each other, aesthetically and emotionally.

But like most mythic couples, their love falls prey to hubris. After all, Asterios was the birth name of the Minotaur, an unlovable monster trapped by Daedalus’s labyrinthine take on a simple design problem. Asterios does not see how the idea of utopia—in design and, by extension, in love—can hem in the imagination until there’s room left for only one person’s construction of the rules of art and life. Asterios’s narcissism, we are meant to believe, is intimately connected to his inflexible aesthetic beliefs—“the certitude of symmetry, the consonance of counterpoise” and the “eloquent equilibriums” that inspire his impossible-to-build designs. He holds on to these beliefs at great cost. Hana divorces him fiercely and suddenly, leaving Asterios to grieve in a labyrinth of his own making.

Like most tragic heroes, Asterios is given the chance to redeem himself. After a fire destroys his New York apartment, Asterios takes a despairing bus ride into the heart of Middle America—the East Coast academic’s descent into the underworld. There, in a small town named Apogee, he finds a job as a car repairman, working for a burly auto mechanic named Stiff Major and living with Stiff’s family, his clairvoyant wife Ursula Major and their son Jackson. Stripped of his pretensions and worldly possessions—the Breuer chairs, the van der Rohe lounge—Asterios begins to build. Out of a pile of reclaimed wood, he and Stiff decide to make a tree house for Jackson. “I’m no Frank Lord Wright,” Stiff claims as he thrusts a crumpled piece of paper at Asterios, “but I made a little sketch.”

Ironically, it does look a little like one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s houses, a modest tip of the hat to Fallingwater and its intimate rapport with nature. Nestled in the treetops, its roof cantilevering out over the boughs, the tree house is Asterios’s first construction, a collaborative effort between Stiff’s design and Asterios’s own two hands. Mazzucchelli pays special attention to these hands when drawing the construction process. We see them palming the planks as if to test their firmness; we see jolts of energy—normally reserved for the comic book’s “ZAP!” “BAM!” or “POW!” moments—that connect the hammer in Asterios’s left hand to the nail in his right; we see the sinuous tensing in his forearms as he grips at the rope that binds the planks to the tree, reuniting the discarded wood with the nature whence it came. From building comes a different way of being and—literally—of being in touch with the world, one that trades the siren song of utopia for the smaller delights of handicraft. Only now can Asterios return to Hana, armed with an appreciation for working together to build something that endures. Only now can she forgive him.

From Asterios Polyp, we could go back to architectural theory—to Martin Heidegger, author of the slim and intractable essay “Building Dwelling Thinking,” which considers the world-making powers of built space; or Emmanuel Petit, who in a recent issue of Log celebrates the possibility of a sensual, even organismic closeness between people and interiors. But it is more illuminating to connect the devotional handicraft of Asterios Polyp to architects who have paid homage to the human hand in practice, like Pierre Chareau, William Morris, or, more recently, Tom Kundig. Chareau’s most famous commission, the Maison de Verre, may seem more sophisticated than Asterios’s tree house—it was once the preferred meeting place of Walter Benjamin and Jean Cocteau in Paris—but its design honors similar principles. Every corner is nimbly packed with gadgets and gizmos: spinning gears, rotating levers, extendable hinges and pivoting surfaces whose kinetic essence encourages or even demands their obsessive use. Here the hand is key. By touching, turning, pressing and pulling on skylights and walls, one can alter the parts of the house that are crucial to its design, thereby participating in its authorship. Far removed from the architect of utopia, who lords over an unreal city, the shared human touch is what makes building—and buildings—desirable, now and into the ever-shifting future.

●

Perhaps no recent work of comic art has enjoyed as much praise from readers and illustrators alike as Chris Ware’s Building Stories. Reviewing it, Daniel Worden speaks of Ware’s architectural “nostalgia for an earlier industrial era,” and compares the Chicago brownstone that sits at the center of Building Stories to “a ruin”—an “aesthetic object” that elicits “melancholy” for the irrecoverable past. Indeed, Ware’s tale of an unnamed woman overcome by depression, anxiety, self-doubt and ennui sprawls masterfully across fourteen pieces of text—a handful of books both large and small, newspaper pullouts, pamphlets, even a board game. It also covers nearly one hundred years in the life of a Humboldt Park brownstone, one that has succumbed to the kind of shabby gentility that precedes demolition. But for most readers, unused to spending this much time with a building, poring over the thousands of angles from which Ware has chosen to draw it, Building Stories exudes an immediacy that the ruin denies. Like Asterios Polyp, it extends the promise of shared creation: by touching and turning and arranging the pieces of Building Stories, you can build your own story, inhabit your own intimately knowable and narrateable world.

Ware has claimed that architecture is “the aesthetic key to the development of the cartoons as an art form.” (Ware’s notebooks and sketches from the past two decades are chock-full of statements like this.) But we could just as easily flip his observation, and claim that Building Stories’ intimate sense of touch unlocks radical ways of sensing buildings—as conscious, powerful and motivated; buildings as not merely aesthetic objects, but subjects unto themselves. In Building Stories, the building narrates its own history in a fusty, cursive hand that trails in and out of its rooms like an absentminded great-aunt, pausing here and there to run a finger over a pair of dusty end tables and reminisce. “It relied on the memory of tenants to stay alive,” the building thinks of itself, as it sheds a shingle to mourn the memories of tenants past:

Buried in these recollections is a serious provocation: If you tickle us, do we not laugh? Where it once seemed impossible for fiction to imagine the inner states of human beings dissimilar to us, Ware dares us to embody the consciousness of something nonhuman and, in doing so, to consider our incommensurable senses of touch. If you were a building, what would it feel like to have your joints tickled? Your knobs twisted? How might you experience the weight and warmth of the human body, its cleanliness and color? Is this building’s lingering “oh!” a cry of pleasure or pain or something else entirely? Is it a sensation that we cannot reroute by way of our all-too-human metaphors?

We could interpret Ware’s provocation to imagine how a building feels on its own terms as radically severing Building Stories from the human point of view. But Ware’s building is never entirely separate from the consciousness of the building’s third-floor tenant, the unnamed woman who lost her left leg in a motorboat accident. Pink-cheeked, a little dowdy, depression-prone and unshakably lonely, she is most often seen hobbling from room to room, wondering what to do with her life. Over time, her body and thoughts seem to map the building’s interior spaces. “Having spent an unusual amount of my childhood sitting on the floor,” she writes in her diary, “I became more than a little acquainted with the world of baseboards, doorstops and electrical plugs, to say nothing of all the valves and faucets that hide behind toilets and sinks.” In a moment that recalls Chareau’s house of gadgets, she confronts an overflowing toilet with her crutch—an extension of her body—plugging it into the toilet’s fill valve to stop the water from running. “I was sort of proud of myself for figuring this out,” she confesses, “You just don’t realize how much you take things for granted until they’re taken away … how interdependent the ‘modern’ world is.” It is the interdependence between humans and buildings—the fusion of the tactile with the tectonic—that provides the woman a rare break from her numb resignation. No matter how sad or small this connectivity might seem, it is one of the only ways for her to be and to feel in relation to the world.

Today the house of fiction is full of such “alien phenomenologies,” to borrow a term from critic and graphic designer Ian Bogost. But Ware suggests that they are largely absent from the esteemed buildings of American architecture, whose imaginative possibilities seem foreclosed by their iconicity. In one of Building Stories’ newspaper-sized pamphlets, Ware airlifts his readers from Humboldt Park to Oak Park, the leafy suburb that is home to many of Frank Lloyd Wright’s early homes, including the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio. (Built in 1889 with a loan from his employer Louis Sullivan, the Wright Home effectively launched the career that would dwarf Sullivan’s own by the next decade.) A century later, Ware’s unnamed woman walks down the streets of Oak Park huffing at the Wright Home’s status as a mere “tourist attraction.” Against the vibrant greens of springtime, there it sits, a flat and uninviting slab of art. “Sometimes I really hate it here,” the woman thinks as she pushes past the horde of gawping German tourists who clog the sidewalk. The tourists need to be reminded that “people still live and work” around these parts, but it’s not entirely their fault. In becoming iconic and therefore uninhabitable, the Wright House has forsaken its contact with the life of the imagination. It can no longer offer the kinds of in-touch experiences that the brownstone delights in. (We could say the same of any contemporary architect who aims to fix an icon, rather than create a space for dwelling.)

For Ware, there is a radical and touching interdependence between humans and things, designers and dwellers, form and everyday function. “Not to brag, but we buildings are able to—how might you say it—grope our way around the future a bit,” the brownstone announces, groping its way to a prophecy: its lonely tenant will marry a young architect whom she meets at a friend’s party and invites up to her apartment one evening in an act of unprecedented bravery, leaving the building vacant and alone. Eventually the bulldozers and wrecking balls will come for it. But it will not be gone—at least, not entirely. In what could be considered one of the strangest panels in Building Stories, Ware flashes forward 150 years to a man and a woman standing where the building had once stood, their heads encased by a virtual interface that is busy pulling “memory fragments” from “this area’s consciousness cloud.” As they read the building’s memories, visualizing its inhabitants and recording their feelings, the woman reflects on the self-centeredness that once obscured from human beings the truth about our existence. “People really did think they were just single particles back then,” she observes in disbelief.

Against the ego and narcissism of big utopia, against its desire for absolute control, the paper architecture of graphic novels gives us a simple alternative: let us grope our way into the interdependent future—one small, delightful touch at a time.

If you liked this essay, you’ll love reading The Point in print.