When Amy Chua published an article in the Wall Street Journal last January entitled “Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior,” people were offended. The article—an excerpt from her memoir, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother—makes the case for a “Chinese” style of parenting in brutally honest terms. Chua, a professor of law at Yale and mother of two daughters, observes that “Chinese” parents produce many more “math whizzes and music prodigies” than “Western” parents. This, she claims, is the fruit of a style of parenting that values academic excellence, musical genius and, above all, success, and which does not shy away from imposing strict rules and restrictions, hard work that verges on torture, and despotic punishments. The Western style—with its emphasis on playing sports, having fun and building self-esteem—is by contrast woefully flaccid.

To illustrate her point, Chua describes her own parenting techniques: she never allowed her daughters to earn less than perfect grades (an A- or second place was unacceptable); even on vacation she forced them to endure three-hour piano and violin practice sessions without food or bathroom breaks (once, when her then three-year old daughter disobeyed, she made her stand outside in freezing weather); she used threats and extortion to force them to excel (when her younger daughter resisted learning a piano piece, Chua “threatened her with no lunch, no dinner, no Christmas or Hanukkah presents, no birthday parties for two, three, four years”). The only extracurricular activities she allowed her daughters were those in which they could win a medal (and that medal had to be gold)—“loser” activities like crafts, theater, television, sleepovers and dating were forbidden. Chua never mentions corporal punishment, but she does think it perfectly acceptable to call one’s children fat, lazy, stupid or worthless—so long as it is done out of love and for the children’s own good. She once told her older daughter she was “garbage.”

Chua knows such methods might horrify Western parents, who believe that children should be allowed to pursue their own passions. But she argues that the indulgence of the Western approach is misguided; parents who do not sufficiently push children to realize their full potential end up secretly disappointed in them, or, worse, unable to admit their disappointment to themselves. “Chinese” parents have an entirely different mindset; since they know what is best they can push and prod their children to achieve it.

Chua’s own career reads like an advertisement for the parenting style she champions. The eldest of four daughters, she was raised by “extremely strict” Chinese immigrant parents and yet “had the most wonderful childhood!” Not only was she not scarred for life, but she graduated first in her high school class of 350, went on to study at Harvard, and has taught at Duke and Yale. She has written books on free-market democracy and the formation of empires, and was reportedly paid a six-figure sum for her memoir. Her two daughters appear to be well on track to replicate their parents’ success (Chua’s husband, Jed Rubenfeld, is a fellow Yale faculty member and the author of best-selling mysteries): in addition to getting straight A’s, her daughters have won numerous musical competitions, and at fourteen one won a competition to play at Carnegie Hall.

The purported moral: if we follow Chua’s parenting methods, our children will also be successful, rather than losers with high self-esteem. The evidence, she implies, is incontrovertible—straight A’s, gold medals, admission to the Ivy League. You can’t argue with success.

●

The responses to “Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior” were predictable. Chua was denounced as a “monster” and a “menace to society.” One reader compared her to a cannibal: “Chua’s voice is that of a jovial, erudite serial killer—think Hannibal Lecter—who’s explaining how he’s going to fillet his next victim.” Many were convinced that Chua’s parenting methods amounted to criminal child abuse:

In my ideal world, Child Protective Services agents would swoop down on the Chua household and whisk her poor kids off to a foster home while coppers slapped her in cuffs. Amy Chua is not only a sick, demented woman and a terrible mother, she’s a prime example of why East Asian cultures are so hopelessly fucked up.

More reasonable critics rehearsed familiar arguments. Many claimed that Chua’s approach is lacking in one way or another—it neglects to emphasize essential social and leadership skills, does not foster creativity or passion, inhibits critical thinking and defines success too narrowly. Children raised this way may grow up to be responsible, hard-working and successful hoop jumpers—doctors, lawyers, engineers and accountants—but not leaders, creators or “mold breakers” who have the ingenuity and audacity to rise to eminence or change the world. Others argued that for these children “success” comes at the cost of happiness. Fun, pleasure and joy are devalued; life appears as nothing but toil. Children who are taught to privilege academic success are more likely to suffer from stress and depression. Chua herself admits she is “not good at enjoying life”; she left the fun parts of parenting to her husband.

Asian Americans raised by parents like Chua have been especially vocal about the psychological damage that her methods inflict. “Parents like Amy Chua are the reason why Asian Americans like me are in therapy,” writes one blogger. What appears as discipline or “tough love” from one perspective often appears as abuse from another. This often leads to gridlocked conflict, unwillingness to empathize, festering resentment and long-lasting family strife. “I’m horrified that she’s American-born and hanging on to this,” the blogger continues, “when most of us are trying to escape it.”

The intense hostility underlying even the most measured responses suggests that Chua has touched on real ethical questions. Critics deeply ensconced in our current meritocracy question only the efficacy of her method; the New York Times, for example, asked: “Does strict control of a child’s life lead to greater success or can it be counterproductive?” But this kind of question simply assumes that success is the highest goal in life, and that the value of a particular style of parenting is to be measured in terms of it. On the other hand, asking, “Will this approach lead to happiness?” also fails to get at the true challenge that Chua poses, since it simply presupposes that the goal of raising kids is happiness. What the controversy surrounding Chua demonstrates, however inadvertently, is that parenting techniques are always grounded in basic assumptions about the way things are and what matters to us. And they are always guided by some answer to the most fundamental of ethical questions—how to live?

●

Chua is wrong to call her parenting ethos “Chinese.” Her parenting methods actually belong to a very specific culture (Confucian), class (middle), and experience (immigration). I know, because I was raised according to the same ethos, although I had the Korean, West Coast, lower-middle class version.

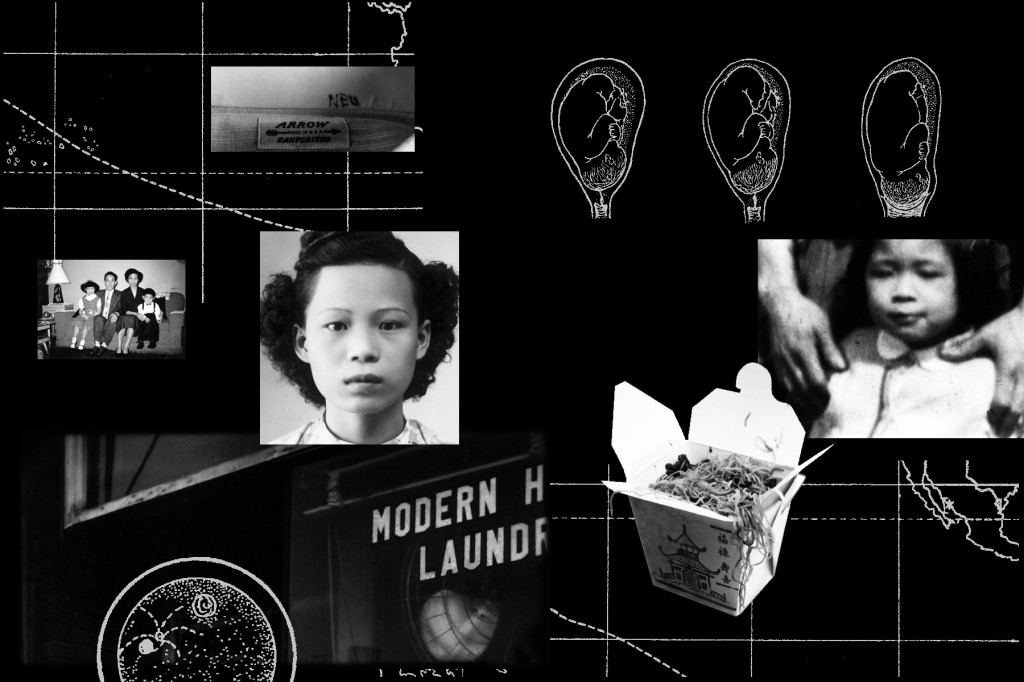

Every ethos needs a hero—someone who perfectly embodies its highest virtues. In my family mythology (as my mother tells it), that hero was my father. Here was a man who came from nothing, but through native intellect and sheer force of will managed to reinvent himself as the proverbial self-made man. He was a “country boy” by birth, the second son of a farmer too poor to buy him eyeglasses to see the blackboard at school, or to bribe the teacher to seat him in the front of the class. Still, he managed to earn top marks on the national college entrance exam and win a full scholarship to the best university in Korea, where, inexplicably, he chose to study German Idealist philosophy. For a time, he was something of a dissident, and dreamed of becoming a philosopher. But at the age of 30, he left Korea and came to America with a wife, a two-year old daughter (me), two suitcases and $200. He did menial labor by day and attended a vocational school at night; my mother worked in a garment factory. But my father’s intelligence, skill and confidence were so evidently exceptional that he was hired on the spot by the organization where he has now worked for nearly forty years, first as a computer programmer, then as a systems analyst and eventually as a top-level manager. (Today, at the age of seventy, he still cannot bring himself to retire.) We moved from our roach-infested quarters in Koreatown to a second floor walk-up in a nicer neighborhood, bought a brand new Chevrolet Impala, and never looked back. He shot from one promotion to the next, and by the time I was nine, a long-anticipated son was on the way, and we were increasingly well-off. My mother would brag, “We came to America with two bags and $200. Look at your father now. He drives a Lexus.”

The point of life was success, and success could be achieved through monomaniacal hard work. Happiness was beside the point. At best, happiness was the incidental by-product of success and respectability.

That was the core of my parents’ ethos, the same ethos taken for granted by Chua. It isn’t some Chinese wisdom imported to a new culture; rather, the Tiger Mom parenting ethos was born out of a specifically American experience—that of its Asian middle-class immigrants. Historically, Asian cultures have been intensely hierarchical, but the wars and revolutions of the twentieth century undermined many traditional social hierarchies, paving the way for a new middle class to emerge. Within that middle class, social status is achieved through a meritocratic free-for-all in three areas: academic credentials, competitive accolades and career achievements. Those members of the new middle class who emigrate are precisely those most committed to a meritocratic ethos. Having forsaken all inherited social status, their status in their adopted country is entirely a matter of academic, competitive and professional success. And success, they have to believe, can be achieved through sheer effort.

This new immigrant ethos not only shapes Chua’s parenting, but pervades her whole approach to living. We can see what distinguishes this ethos—its fundamental commitments and values, its benefits and shortcomings—through Chua’s basic attitudes toward education, culture and work.

Education is highly valued by the Tiger Mother, it is true, but its value is purely instrumental. It is a means to an end, not an end in itself—a path to success rather than something worth doing for its own sake. Even higher education is not seen as an apprenticeship in the examined life, but as a series of hoops to jump through on the way to a successful career. Hence the strangely mercenary approach to school: what matters is not learning but grades. This is why Chua focuses less on the intellectual and ethical growth of her children than on their academic marks. My parents were the same: they did not care what I was learning, or even whether I was learning anything at all, as long as I was earning A’s. We can imagine how admissions decisions would be handled if someone like Chua were to get on the admissions board at Harvard or Yale or any other highly selective institution (skateboarders and drummers need not apply).

The Tiger Mother also does not see work as a valuable end in itself, but only as a means to two other ends—success and respectability. The demand for success reflects the traditional expectation that children will eventually support their parents in old age. The demand for respectability reflects the notion that a child’s choice of career will bring honor or shame on the family as a whole. From this point of view, the common American belief that young people should be free to do what they love seems to be the height of ingratitude and selfishness. The idea of a calling, of devoting oneself to work that one loves and finds intrinsically rewarding, is foreign to this world. Instead, work is seen through a strict hierarchy of professions—with medicine, law and engineering at the top—and there is intense pressure to choose a profession that reflects well on one’s parents. This is why Chua’s father is an engineer, why she herself is a law professor, and why her daughters are on track to replicate their success. My parents were the same way: my brother has followed my father’s career; my sister is a doctor; I was supposed to be a doctor too.

The Tiger Mother is no philistine per se, utterly indifferent to culture and fine arts. But neither does she value culture for its own sake. Instead, her attitude exemplifies what Hannah Arendt called “cultural philistinism,” the use of art and culture by the middle classes to distinguish themselves from those beneath them: “In this fight for social position, culture began to play an enormous role as one of the weapons, if not the best-suited one, to advance oneself socially, and to ‘educate oneself’ out of the lower regions.” This attitude towards art and culture plays out in Chua’s household. Her daughters were not allowed to choose what to do with their free time; their activities had to be the kind that would look good on a college application (“Not just any activity, like ‘crafts,’ which can lead nowhere—or even worse, playing the drums, which leads to drugs”). They had to do music instead of drama (you can’t win a medal for your performance in a play). They could not choose which musical instruments they would play (for there is a strict hierarchy of musical instruments, with violin and piano at the top and percussion clearly at the bottom). This attitude also explains Chua’s devotion to the cult of virtuosity: the point of a musical performance is not to express oneself or to create something beautiful but to demonstrate the kind of technical proficiency that wins competitions.

My parents had humbler origins than Chua’s. Her parents went to MIT and earned advanced degrees; her father is a professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences at UC Berkeley. Although my parents went to the best universities in Korea, they essentially had to start from zero when they immigrated; in America we were definitely closer to the lower end of the middle-class spectrum. But my family was no exception to the universal rule that the middle classes need to distinguish themselves from those one step below. The distinction between blue collar and white collar work was paramount. The ideal was to secure a “desk job” that would keep you from getting your hands dirty, provide a steady salary, good health benefits and a comfortable, respectable life.

Instead of Chua’s upper-middle class focus on cultural achievements, my parents focused on bourgeois consumerism. Chua traveled with her daughters to foreign countries and took them to museums; she lists 39 cities, including London, Paris, Nice, and Rome, that her daughters had visited by the time they were 12 and 9. My parents never took me to a museum and they thought traveling was a waste of money. We never took trips that required us to fly anywhere—vacations had to be within driving distance. Instead, my parents spent money on objects. A brand new house in a brand new neighborhood was the ultimate purchase. “Used” houses were inferior. To buy a used car was unthinkable. Luxury sedans—a Benz or a Lexus—were a non-negotiable necessity (we did live in Southern California). When I dared question this mentality, my mother patiently explained, “The kind of car you drive shows the world the kind of person you are.”

When it came to academic achievement, the sights were not set as high. My parents did not save money for our college educations. The ideal was to win a scholarship to a big-name university—as my father had done—but short of that we were expected to go to the University of California. UC Berkeley was considered “just as good” as Harvard or Yale. UCLA was second best. An above-average student who made mostly A-’s and B+’s without much effort, I went to UC Irvine, which ranked a distant third or fourth. At least I didn’t end up at UC Riverside. The sense was that, “It would be great if you were to win a scholarship to Harvard—your father did something like that—but if not, UC Irvine is good enough.” My parents would never have paid for me to go to a private liberal arts college no one in their social milieu had ever heard of. What would be the point?

Nor were the sights set as high for professional success. My parents never questioned the value of success, but their understanding of it evolved over time. There was a strange tension between their abiding faith in American meritocracy and their growing but hazy awareness of the limits of that vision. They arrived in America thinking the apex of success was to be a doctor, engineer, lawyer or top-level manager. They spent their lives climbing to the pinnacle of their social milieu, but when they got to the top the clouds parted and they saw that they were surrounded and overshadowed by peaks they never knew existed. And they were tired of climbing. They came to realize that higher mountains were out there—the Harvards and Carnegie Halls of the world—but felt that they were out of reach, and there was no point in wanting the impossible. At a family dinner, my father even prayed that my husband and I would have “ordinary lives.” In retrospect, I think the prayer was directed to me, as if he had been saying, “Don’t aim for greatness. Be content with success in a respectable middle-class profession.”

Unlike Chua, I rebelled. Early on, my parents wanted me to become a doctor, lawyer or engineer, and I had enrolled at UC Irvine as a biology major. But after a year and a half, and without consulting my parents, I got off the pre-med track and hopped a freight train heading nowhere: I chose to study not what was prestigious or respectable but what I loved (literature and philosophy). My parents stopped paying for my education, and I had to work as a temp and teaching assistant to put myself through the rest of college and graduate school. When I finally got my Ph.D., I asked my mother, “Are you proud of me now?” Her response was, “We never asked for that.” This has not been good for our relationship.

●

Precisely because I was raised in a Tiger Mom world, but rebelled against it, I understand where Chua is coming from, but I can also see what remains invisible to her. Being a Tiger Mom is not just a matter of using harsh parenting techniques to ensure that children live up to their potential. It involves seeing one’s whole world—one’s work, prospects for happiness, family ties, sense of obligations, sense of self, etc.—from the perspective of an immigrant drawn to America’s meritocratic mythology. And this makes conflicts between Tiger Moms and their children almost inevitable.

The situation of a person born into poverty in a war-torn country obviously differs from that of a person born and raised in conditions of (relative) prosperity. For the Asian immigrant who has left everything behind and has nothing to fall back on except his or her own efforts, “succeeding” is an all-consuming compulsion. Straight A’s, gold medals, promotions and Nobel Prizes are not simply the rewards of one’s hard work but evidence of one’s worth. They are not goals which, having been reached, can be enjoyed in and of themselves. Specific achievements are never enough; they do not slake but rather fuel the desire for success.

It is this urgent quality of drivenness that the children of Asian immigrants may not feel in their bones. Simple desire for success they can understand; what is alien to them is their parents’ desperate compulsion toward it. The child raised with a community of intimates who value her for herself will find it bizarre to stake her sense of personal esteem on public affirmations of success. What matters to my father is not that he works in software development, but that he is in a senior position. My siblings and I, on the other hand, are more defined by the kind of jobs we chose (physician, computer programmer and humanities professor). Success matters, but the specific job matters more.

Tiger Parents often live in isolation from the culture of their adopted country, and foolishly expect their children to do the same. But children pick up ideas the same way they pick up germs: inevitably and incessantly. Floating around them are messages like: “Be yourself”; “Do what you love”; “Have fun”; “Follow your bliss”; “Believe in yourself.” And when well-meaning people ask Tiger Mothered young adults whether, for all their success, they are truly happy, the question can be profoundly disquieting; for the first time, their most basic assumptions are thrown into doubt.

Asian families are notorious for their bitter feuds and decade-long estrangements. The high drama, the suicides, estrangements and disownments show that what is at stake is the whole way of being of the family, that is, everything that gives the family its identity and raison d’être. In a Moscow restaurant—what better setting?—Chua’s daughter smashed a glass on the floor and rebelled, not just against her mother’s discipline but in protest against her family’s whole ethos: “I hate the violin. I hate my life! I hate you, and I hate this family!”

I have an aunt who has not spoken to her mother (my grandmother) for more than forty years, as long as I have been alive. They will go to their graves before they make their peace. I know a Korean American young man who, after years of kowtowing and deception, finally blew up at his parents and told them what he really thought and how he really lived; they responded by disowning him and telling friends and neighbors he was dead.

As absurd as it may appear from the outside, the histrionics make sense as a response to a Manichean logic that sees the world as an arena of non-stop competition that sorts humanity into winners and losers. Since children’s success or failure brings honor or shame directly on their parents, parents have every reason to mold their children by any means necessary. But headstrong mothers breed headstrong daughters, and it is understood that one fights fire with fire. So Tiger Parenting can generate conflict far beyond anything Chua describes: public meltdowns; destruction of property; displays of self-mutilation; and violence involving knives, kitchen utensils, gardening tools and household appliances. Such tactics are not only perfectly appropriate, but proofs of one’s mettle. Whoever has the most impressive and forceful display of emotion prevails.

When the “Asian” style of parenting fails, it does so in the saddest and most self-destructive ways. My cousin slashed her wrists in the bathtub where her mother found her lying in a warm mix of water and blood (she survived). At Cornell, thirteen of 21 suicides between 1996 and 2006 were Asians or Asian Americans (who constituted only 14 percent of the student body at the time). In this country, Asian American women have the highest rates of suicide. It is irresponsible self-deception to maintain that the children of Tiger Moms suffer no ill effects from the way they are raised.

●

I have lived and left behind the Tiger Mom way of life, and I am convinced that Western ways are better. In contrast to Tiger Mom parenting, Western parenting rightly recognizes that childhood is a time to be treasured for its own sake, that we should “let kids be kids.” Accordingly, Western culture is filled with works of art that exalt and celebrate the intrinsic worth and dignity of childhood—from William Wordsworth to A. A. Milne. In Winnie the Pooh, Christopher Robin says, “What I like most of all is just doing nothing.” The tragedy at the end of the book is that Christopher Robin has to go to school: “No one else in the forest knew why or where he was going, just that it had something to do with twice-times, and how to make things called ABCs, and where a place called Brazil is.”

But I also think Western ways of parenting are in trouble. The ideas that commonly guide parents today are actually debased and derivative versions of an ethos that has been reduced to clichés (e.g., “Be yourself”; “Do what you love”; “Live your own life”). Rather than simply attacking Chua and reaffirming Western ways of parenting, the task before us is to recover and articulate our own ethos.

At its best, the Western style of parenting aims to help children live authentically, that is, to take on the responsibility to decide for themselves what to do and how to live. My understanding of the world is inauthentic to the extent that I have simply inherited it from my parents or absorbed it from the people around me, without having made any responsible effort to measure it against my own experience. My discourse is inauthentic if I accept and repeat what others say without trying to understand through my own effort what it means or whether it is true. Inauthentic understanding and discourse are dominated and governed by the dictatorship of “the everyone” or “the they,” as the German philosopher Martin Heidegger writes:

We enjoy ourselves and have fun the way they enjoy themselves. We read, see, and judge literature and art the way they see and judge … we find “shocking” what they find shocking. The they, which is nothing definite… prescribes the kind of being of everydayness.

In contrast, what is authentic is what is our own—what we have that we have made our own. My understanding and discourse is more authentic the more it comes out of my own experience, thought and judgments. My life is more authentic the less it is dominated by “the everyone” and the more it is governed by my own understanding, concerns, desires, tastes, goals, etc. One of the clearest articulations of this idea of authenticity comes in Leo Tolstoy’s novella, The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Tolstoy tells the life of a man who becomes successful and respectable by ignoring his own moral intuitions and living according to the bourgeois values of “the everyone”:

As a student he had done things which, at the time, seemed to him extremely vile and made him feel disgusted with himself; but later, seeing that people of high standing had no qualms about doing these things, he was not quite able to consider them good but managed to dismiss them and not feel the least perturbed when he recalled them.

Tolstoy doesn’t tell us what exactly Ivan Ilyich did; he doesn’t denounce this or that immoral act. The point is that Ivan let his own sense of good and bad be overruled by the dictates of common opinion. The tragedy of his life is not that he failed to achieve something, but that the ideals he did succeed in reaching were not truly his own. The novella has often been read as a condemnation of the bourgeois ethos whose highest values are success and respectability. It has also been read as an indictment of conformism. While both these readings are plausible, at the deepest level the novel is about inauthenticity. What is wrong with Ivan Ilyich’s life is not just that it was guided by a narrow and superficial set of values, but that Ivan simply accepted those values without questioning them.

The ethos of authenticity undergirding Western parenting can be seen in Western attitudes toward art, education and work. Unlike in the Tiger Mother ethos, art and education are seen as ends in themselves, rather than means. Both are considered essential for cultivating an authentic engagement with the world—which involves casting aside the opinions of the “everyone” in favor of developing one’s own. This ideal of authenticity even guides Western attitudes toward work, especially the notion that children should be free to choose their own career, which reflects the old Western idea that work should be experienced as something we are personally called upon to do. No one else can decide what my calling is; only I can find the work that is properly my own.

Grafted onto these attitudes is the sense that in life it is possible to aim at something higher than success. Success is good, but more important than success is greatness. In this ethos there is a peculiar place of honor for people who were great without being successful. Vincent van Gogh failed as an art dealer and as a Christian missionary before finally cutting off his ear, being put in an insane asylum and killing himself at the age of 37. He was not a success, but success seems petty next to his greatness as an artist. This aspiration to greatness is absent from every instrumental attitude to art, education and work. Nothing great has ever been achieved by people who see such things solely as instruments for achieving success and respectability.

●

Chua is perhaps at her most “Chinese” when, in response to her husband’s argument that children don’t owe their parents anything, she remarks, “This strikes me as a terrible deal for the Western parent” (my italics). On a gut level, she can’t think of the relation between parents and children in terms other than debt and obligation, so her husband’s objections simply make no sense. My mother once said, as if she were speaking of life on Mars, “Here [in America] the parents are the slaves of their children.” What she saw of American parenting violated her deepest sense of the natural order of things. Despite having lived in America for nearly forty years, the country remains for her a baffling world in which all that is good and right and proper is turned on its head.

The nature of the differences between Asian Americans and their immigrant parents entails that conflict cannot be resolved through the channels taken for granted by Western families, such as negotiation and reasoned dialogue (like I said before, colorful and sustained displays of emotion and violence are the more effective and accepted means of getting through to the other). Once, when I had a particularly bad argument with my mother—we hadn’t talked for months—a concerned relative of my husband’s asked, “Why can’t you just sit down at the table and talk things through?” What he couldn’t fathom was that that would have been impossible. To sit down at the table with me would have been, for my mother, an admission of defeat. Ahab and Moby Dick do not sit down at the table and talk things through!

Westerners tend to think of disputes in terms of the metaphor of perspective: each person has a standpoint which gives them a distinct perspective, and each perspective offers a clear but limited view of the world; no one perspective is comprehensive, so disputes can be resolved by exchanging opinions and finding the grains of truth in many different points of view. Tiger Parents, on the other hand, tend to think of disputes in the metaphor of a path: there is one true path that their children ought to follow, and any deviation from that path is a sign of error or delinquency. Americanized children cannot accept the basic terms in which their parents think, since those terms deny that different opinions have any legitimacy. The parents in turn cannot accept the terms in which their children think, since that would be a deviation from what they regard as the rightful path. To regard other ideas as “different perspectives” would be to admit their own way of thought might be in error.

These differences are made all the more irresolvable by the fact that Tiger Parents perceive the conflict between parents and children as a battle of wills in which there can be only winners and losers (to compromise is to lose). Hence the title of Chua’s book, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. When Chua “retreated” in the face of her daughter’s meltdown, she suffered a tactical defeat. But the basic terms in which she thinks of parenting didn’t change. She may have lost one skirmish but she still thinks of parenting as a war of attrition. In the case of one daughter, hostilities apparently commenced when the girl was only three: “I was determined to raise an obedient Chinese child … if it killed me.” When her daughter dared to defy her—by refusing to play the piano or come in out of the cold—Chua realizes, “I had underestimated Lulu, not understood what she was made of. She would sooner freeze to death than give in.” However, Chua quickly rallies: “But Lulu had underestimated me too. I was just re-arming. The battle lines were drawn, and she didn’t even know it.”

Asian American fiction is filled with fantasies of conflict resolution. After a series of misunderstandings and personal crises, the mother and daughter have a meeting of hearts which allows them to better understand and appreciate one another. It turns out that the mother (or grandmother) was right after all; but at the same time, the mother learns to give autonomy and respect to the daughter. This typical narrative is pure wish fulfillment; the underlying fantasy is that differences are all a matter of misunderstanding. Stories like these appeal to Asian Americans because they articulate exactly what we want, which is to believe that real reconciliation is possible. But the fantasy, understandable as it is, obscures the depth of the differences at issue and fails to appreciate what it is that makes real-life reconciliation so difficult.

Some children do live more or less according to their parents’ ethos. I know a Chinese American student who came from a family of doctors and was happy to follow in their footsteps and enroll at Harvard Medical School. But many Asian Americans can imitate their parents only by suppressing their real values. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer believed that most human beings are doomed to be unhappy but that nature nevertheless produces a few people who are genuinely happy, who serve as “decoys” and who make people even more miserable by creating the illusion that happiness is possible. The children who genuinely adopt their parents’ ethos, like this Chinese American legacy doctor, are the Schopenhauerian “decoys” of the Asian American community.

The easiest alternative is to pretend. Keeping up appearances while sneaking around behind our parents’ backs is a long and cherished tradition within the Asian American community. The most resourceful children, typically daughters, know there are many shades of acceptable pretense. It is simple enough, for example, to put on a show of obeisance in the presence of one’s parents and then turn around and do whatever the hell one pleases as soon as they are out of sight. Some families have a kind of “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. Or one can simply lie. What may appear as “Asian” hypocrisy and sneakiness from the outside is often the only solution to a desperate situation: parents are appeased; children get some breathing room; harmony reigns; everyone wins. All it takes is a little creativity. I have a Korean American friend whose boyfriend moved in with her for two years without her parents’ knowledge or consent. This meant that for two years her boyfriend could never answer the phone, for fear that it might be her parents calling. Whenever her parents visited, they had to evacuate his possessions and erase all trace of his presence from their apartment. She explained, “It’s better that way. They didn’t need to know. They didn’t want to know. Why stir up conflict? Later we got engaged and then married. So it all worked out.”

But pretending has its limits. Usually it works for a while and then one has to start making decisions that can’t be hidden. Dan Choi, the gay Korean American lieutenant who challenged the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, has said that the hardest thing about his experience was coming out to his family (his father is a Baptist minister). After enduring relentless pressure from his mother to marry a Korean girl, he had no choice but to come out; he told her, “I am not going to marry a Korean girl, nor am I going to marry a White girl. I am gay.”

Sometimes you have to rebel, even if it means cutting yourself off from your parents. Obviously this isn’t ideal—you end up with no family. I know from experience: I finally stood up to my mother two years ago and I haven’t seen or spoken to any member of my family since. (Although I have exchanged e-mails with my father and siblings, and my mother and I are now “friends” on Facebook.)

●

A real reconciliation would have to begin with a reframing of the conflict. The conflict between Tiger Parents and their children may not be a battle between right and wrong but a collision between right and right. What is ultimately at stake is the differences between two êthea—two visions of what it is right to do and good to be. The ancient Greeks had a name for this kind of collision between right and right: tragedy. Tragedies are stories that dramatize conflicts between two sets of values, each of which is worthy of respect. The Greeks saw that such conflicts tend to end unhappily when both sides refuse to listen to or respect the other. But not all tragedies end unhappily; some end with reconciliation.

The Oresteia, for example, is about the conflict between the old and new gods, the new gods who dwell on Mount Olympus and the ancient goddesses known as the Furies, the hideous and bloodthirsty spirits of revenge. The conflict between the gods stands for the collision between the êthea of kinship and citizenship—between traditional codes of honor and revenge that united blood kin, and the rule of law that united citizens in a polis. Aeschylus shows that reconciliation is possible if the new gods of the polis reserve a place of honor for the old gods of the family, and if the old gods are also transformed, in the sense that the code of honor and revenge is retained and yet expanded beyond individual families to encompass the whole city. The sense of kinship had to be extended beyond blood relatives to include the Athenian citizenry as a whole, and the emotions once vented on those who attacked blood kin had to be redirected toward those who attacked Athens. The Oresteia shows that conflicts between different values do not have to end unhappily. Old and new values can be transformed in a way that maximizes the harmony and minimizes the conflict between them. The new gods no longer seek to defeat or repress the old gods, and the old gods are transformed in a way that lets them still be honored and respected.

Perhaps something similar can happen in the conflict between Tiger Parents and their children, and, on a deeper level, in the collision between the êthea of “Chinese” and “Western” styles of parenting. For example, Amy Tan, the author of The Joy Luck Club, has said in interviews that her parents didn’t want her to become a writer: “My parents told me I would become a doctor, and then in my spare time I would become a concert pianist.” But after she became a successful writer, her parents supported her. For Tan, reconciliation did not come through heart-to-heart talks that cleared away misunderstandings. It was just that her rebellion ended up taking a form that was consistent with her parents’ values. As for the Korean American young man I know who was disowned and declared dead by his parents: after a period of estrangement, he was successful enough as a music producer to buy his parents a big new house. All was forgiven, and he was “undisowned” by his parents. He wasn’t dead after all.

In the areas of education and work, at least, it seems there can be some compromise. Children can reject their parents’ understanding of education and work and follow their passions as long as they end up in a place that the parents can respect on their own terms. If Tiger Parents can see that doing what one loves can also lead to success, then there can be a reconciliation between the ethos that regards work as a means to success and the ethos that regards meaningful work as an end in itself. Like the old gods in the Oresteia, the parents’ values can be honored and transformed at the same time.

Of course when it comes to certain conflicts (e.g., when parents want their children to marry within their ethnic group, or when parents of gay children want them to stop being gay) no compromise is possible. Yet the children of Tiger Parents do not have to choose between pure acquiescence and total rebellion. Their task is to find and extract what is worth preserving in the Tiger Parent ethos, and to transpose and incorporate it into a hybrid Asian American ethos.

By discussing Tiger Parenting openly, Chua’s book may actually help Asian Americans take a first step in this direction. For she is actually not a traditional Chinese mother. By publicly discussing what in traditional cultures is simply taken for granted, she does what a true traditionalist would never do: she justifies herself on the basis of arguments, and exposes herself to the indignities of debate. She herself remarks, “I think that writing this book is an extremely ‘Western’ thing to do. I don’t think Chinese people would do it. I disobeyed my mum. My mum said, ‘Don’t write it!’” Just as she once defied dinner-party politesse by announcing to guests that she called her daughter “garbage,” she has now defied the polite and mendacious relativism that claims every style of parenting is “special in its own way.” What is most shocking in Chua’s book is not what she says but that she says it.

Much of the power of a traditional culture comes from the assumption of an authority that does not need to be articulated or justified, so it is refreshing to hear someone willing to argue for an autocratic style of parenting, and to do so in public. By making a case for the Chinese style of parenting, Chua opens, perhaps inadvertently, a much-needed dialogue, not simply about different parenting styles, but about the underlying assumptions on which they are based—assumptions about how to live, the proper relation between parents and children, and what we should aspire to as human beings.

And for that, I thank her.

When Amy Chua published an article in the Wall Street Journal last January entitled “Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior,” people were offended. The article—an excerpt from her memoir, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother—makes the case for a “Chinese” style of parenting in brutally honest terms. Chua, a professor of law at Yale and mother of two daughters, observes that “Chinese” parents produce many more “math whizzes and music prodigies” than “Western” parents. This, she claims, is the fruit of a style of parenting that values academic excellence, musical genius and, above all, success, and which does not shy away from imposing strict rules and restrictions, hard work that verges on torture, and despotic punishments. The Western style—with its emphasis on playing sports, having fun and building self-esteem—is by contrast woefully flaccid.

To illustrate her point, Chua describes her own parenting techniques: she never allowed her daughters to earn less than perfect grades (an A- or second place was unacceptable); even on vacation she forced them to endure three-hour piano and violin practice sessions without food or bathroom breaks (once, when her then three-year old daughter disobeyed, she made her stand outside in freezing weather); she used threats and extortion to force them to excel (when her younger daughter resisted learning a piano piece, Chua “threatened her with no lunch, no dinner, no Christmas or Hanukkah presents, no birthday parties for two, three, four years”). The only extracurricular activities she allowed her daughters were those in which they could win a medal (and that medal had to be gold)—“loser” activities like crafts, theater, television, sleepovers and dating were forbidden. Chua never mentions corporal punishment, but she does think it perfectly acceptable to call one’s children fat, lazy, stupid or worthless—so long as it is done out of love and for the children’s own good. She once told her older daughter she was “garbage.”

Chua knows such methods might horrify Western parents, who believe that children should be allowed to pursue their own passions. But she argues that the indulgence of the Western approach is misguided; parents who do not sufficiently push children to realize their full potential end up secretly disappointed in them, or, worse, unable to admit their disappointment to themselves. “Chinese” parents have an entirely different mindset; since they know what is best they can push and prod their children to achieve it.

Chua’s own career reads like an advertisement for the parenting style she champions. The eldest of four daughters, she was raised by “extremely strict” Chinese immigrant parents and yet “had the most wonderful childhood!” Not only was she not scarred for life, but she graduated first in her high school class of 350, went on to study at Harvard, and has taught at Duke and Yale. She has written books on free-market democracy and the formation of empires, and was reportedly paid a six-figure sum for her memoir. Her two daughters appear to be well on track to replicate their parents’ success (Chua’s husband, Jed Rubenfeld, is a fellow Yale faculty member and the author of best-selling mysteries): in addition to getting straight A’s, her daughters have won numerous musical competitions, and at fourteen one won a competition to play at Carnegie Hall.

The purported moral: if we follow Chua’s parenting methods, our children will also be successful, rather than losers with high self-esteem. The evidence, she implies, is incontrovertible—straight A’s, gold medals, admission to the Ivy League. You can’t argue with success.

●

The responses to “Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior” were predictable. Chua was denounced as a “monster” and a “menace to society.” One reader compared her to a cannibal: “Chua’s voice is that of a jovial, erudite serial killer—think Hannibal Lecter—who’s explaining how he’s going to fillet his next victim.” Many were convinced that Chua’s parenting methods amounted to criminal child abuse:

More reasonable critics rehearsed familiar arguments. Many claimed that Chua’s approach is lacking in one way or another—it neglects to emphasize essential social and leadership skills, does not foster creativity or passion, inhibits critical thinking and defines success too narrowly. Children raised this way may grow up to be responsible, hard-working and successful hoop jumpers—doctors, lawyers, engineers and accountants—but not leaders, creators or “mold breakers” who have the ingenuity and audacity to rise to eminence or change the world. Others argued that for these children “success” comes at the cost of happiness. Fun, pleasure and joy are devalued; life appears as nothing but toil. Children who are taught to privilege academic success are more likely to suffer from stress and depression. Chua herself admits she is “not good at enjoying life”; she left the fun parts of parenting to her husband.

Asian Americans raised by parents like Chua have been especially vocal about the psychological damage that her methods inflict. “Parents like Amy Chua are the reason why Asian Americans like me are in therapy,” writes one blogger. What appears as discipline or “tough love” from one perspective often appears as abuse from another. This often leads to gridlocked conflict, unwillingness to empathize, festering resentment and long-lasting family strife. “I’m horrified that she’s American-born and hanging on to this,” the blogger continues, “when most of us are trying to escape it.”

The intense hostility underlying even the most measured responses suggests that Chua has touched on real ethical questions. Critics deeply ensconced in our current meritocracy question only the efficacy of her method; the New York Times, for example, asked: “Does strict control of a child’s life lead to greater success or can it be counterproductive?” But this kind of question simply assumes that success is the highest goal in life, and that the value of a particular style of parenting is to be measured in terms of it. On the other hand, asking, “Will this approach lead to happiness?” also fails to get at the true challenge that Chua poses, since it simply presupposes that the goal of raising kids is happiness. What the controversy surrounding Chua demonstrates, however inadvertently, is that parenting techniques are always grounded in basic assumptions about the way things are and what matters to us. And they are always guided by some answer to the most fundamental of ethical questions—how to live?

●

Chua is wrong to call her parenting ethos “Chinese.” Her parenting methods actually belong to a very specific culture (Confucian), class (middle), and experience (immigration). I know, because I was raised according to the same ethos, although I had the Korean, West Coast, lower-middle class version.

Every ethos needs a hero—someone who perfectly embodies its highest virtues. In my family mythology (as my mother tells it), that hero was my father. Here was a man who came from nothing, but through native intellect and sheer force of will managed to reinvent himself as the proverbial self-made man. He was a “country boy” by birth, the second son of a farmer too poor to buy him eyeglasses to see the blackboard at school, or to bribe the teacher to seat him in the front of the class. Still, he managed to earn top marks on the national college entrance exam and win a full scholarship to the best university in Korea, where, inexplicably, he chose to study German Idealist philosophy. For a time, he was something of a dissident, and dreamed of becoming a philosopher. But at the age of 30, he left Korea and came to America with a wife, a two-year old daughter (me), two suitcases and $200. He did menial labor by day and attended a vocational school at night; my mother worked in a garment factory. But my father’s intelligence, skill and confidence were so evidently exceptional that he was hired on the spot by the organization where he has now worked for nearly forty years, first as a computer programmer, then as a systems analyst and eventually as a top-level manager. (Today, at the age of seventy, he still cannot bring himself to retire.) We moved from our roach-infested quarters in Koreatown to a second floor walk-up in a nicer neighborhood, bought a brand new Chevrolet Impala, and never looked back. He shot from one promotion to the next, and by the time I was nine, a long-anticipated son was on the way, and we were increasingly well-off. My mother would brag, “We came to America with two bags and $200. Look at your father now. He drives a Lexus.”

The point of life was success, and success could be achieved through monomaniacal hard work. Happiness was beside the point. At best, happiness was the incidental by-product of success and respectability.

That was the core of my parents’ ethos, the same ethos taken for granted by Chua. It isn’t some Chinese wisdom imported to a new culture; rather, the Tiger Mom parenting ethos was born out of a specifically American experience—that of its Asian middle-class immigrants. Historically, Asian cultures have been intensely hierarchical, but the wars and revolutions of the twentieth century undermined many traditional social hierarchies, paving the way for a new middle class to emerge. Within that middle class, social status is achieved through a meritocratic free-for-all in three areas: academic credentials, competitive accolades and career achievements. Those members of the new middle class who emigrate are precisely those most committed to a meritocratic ethos. Having forsaken all inherited social status, their status in their adopted country is entirely a matter of academic, competitive and professional success. And success, they have to believe, can be achieved through sheer effort.

This new immigrant ethos not only shapes Chua’s parenting, but pervades her whole approach to living. We can see what distinguishes this ethos—its fundamental commitments and values, its benefits and shortcomings—through Chua’s basic attitudes toward education, culture and work.

Education is highly valued by the Tiger Mother, it is true, but its value is purely instrumental. It is a means to an end, not an end in itself—a path to success rather than something worth doing for its own sake. Even higher education is not seen as an apprenticeship in the examined life, but as a series of hoops to jump through on the way to a successful career. Hence the strangely mercenary approach to school: what matters is not learning but grades. This is why Chua focuses less on the intellectual and ethical growth of her children than on their academic marks. My parents were the same: they did not care what I was learning, or even whether I was learning anything at all, as long as I was earning A’s. We can imagine how admissions decisions would be handled if someone like Chua were to get on the admissions board at Harvard or Yale or any other highly selective institution (skateboarders and drummers need not apply).

The Tiger Mother also does not see work as a valuable end in itself, but only as a means to two other ends—success and respectability. The demand for success reflects the traditional expectation that children will eventually support their parents in old age. The demand for respectability reflects the notion that a child’s choice of career will bring honor or shame on the family as a whole. From this point of view, the common American belief that young people should be free to do what they love seems to be the height of ingratitude and selfishness. The idea of a calling, of devoting oneself to work that one loves and finds intrinsically rewarding, is foreign to this world. Instead, work is seen through a strict hierarchy of professions—with medicine, law and engineering at the top—and there is intense pressure to choose a profession that reflects well on one’s parents. This is why Chua’s father is an engineer, why she herself is a law professor, and why her daughters are on track to replicate their success. My parents were the same way: my brother has followed my father’s career; my sister is a doctor; I was supposed to be a doctor too.

The Tiger Mother is no philistine per se, utterly indifferent to culture and fine arts. But neither does she value culture for its own sake. Instead, her attitude exemplifies what Hannah Arendt called “cultural philistinism,” the use of art and culture by the middle classes to distinguish themselves from those beneath them: “In this fight for social position, culture began to play an enormous role as one of the weapons, if not the best-suited one, to advance oneself socially, and to ‘educate oneself’ out of the lower regions.” This attitude towards art and culture plays out in Chua’s household. Her daughters were not allowed to choose what to do with their free time; their activities had to be the kind that would look good on a college application (“Not just any activity, like ‘crafts,’ which can lead nowhere—or even worse, playing the drums, which leads to drugs”). They had to do music instead of drama (you can’t win a medal for your performance in a play). They could not choose which musical instruments they would play (for there is a strict hierarchy of musical instruments, with violin and piano at the top and percussion clearly at the bottom). This attitude also explains Chua’s devotion to the cult of virtuosity: the point of a musical performance is not to express oneself or to create something beautiful but to demonstrate the kind of technical proficiency that wins competitions.

My parents had humbler origins than Chua’s. Her parents went to MIT and earned advanced degrees; her father is a professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences at UC Berkeley. Although my parents went to the best universities in Korea, they essentially had to start from zero when they immigrated; in America we were definitely closer to the lower end of the middle-class spectrum. But my family was no exception to the universal rule that the middle classes need to distinguish themselves from those one step below. The distinction between blue collar and white collar work was paramount. The ideal was to secure a “desk job” that would keep you from getting your hands dirty, provide a steady salary, good health benefits and a comfortable, respectable life.

Instead of Chua’s upper-middle class focus on cultural achievements, my parents focused on bourgeois consumerism. Chua traveled with her daughters to foreign countries and took them to museums; she lists 39 cities, including London, Paris, Nice, and Rome, that her daughters had visited by the time they were 12 and 9. My parents never took me to a museum and they thought traveling was a waste of money. We never took trips that required us to fly anywhere—vacations had to be within driving distance. Instead, my parents spent money on objects. A brand new house in a brand new neighborhood was the ultimate purchase. “Used” houses were inferior. To buy a used car was unthinkable. Luxury sedans—a Benz or a Lexus—were a non-negotiable necessity (we did live in Southern California). When I dared question this mentality, my mother patiently explained, “The kind of car you drive shows the world the kind of person you are.”

When it came to academic achievement, the sights were not set as high. My parents did not save money for our college educations. The ideal was to win a scholarship to a big-name university—as my father had done—but short of that we were expected to go to the University of California. UC Berkeley was considered “just as good” as Harvard or Yale. UCLA was second best. An above-average student who made mostly A-’s and B+’s without much effort, I went to UC Irvine, which ranked a distant third or fourth. At least I didn’t end up at UC Riverside. The sense was that, “It would be great if you were to win a scholarship to Harvard—your father did something like that—but if not, UC Irvine is good enough.” My parents would never have paid for me to go to a private liberal arts college no one in their social milieu had ever heard of. What would be the point?

Nor were the sights set as high for professional success. My parents never questioned the value of success, but their understanding of it evolved over time. There was a strange tension between their abiding faith in American meritocracy and their growing but hazy awareness of the limits of that vision. They arrived in America thinking the apex of success was to be a doctor, engineer, lawyer or top-level manager. They spent their lives climbing to the pinnacle of their social milieu, but when they got to the top the clouds parted and they saw that they were surrounded and overshadowed by peaks they never knew existed. And they were tired of climbing. They came to realize that higher mountains were out there—the Harvards and Carnegie Halls of the world—but felt that they were out of reach, and there was no point in wanting the impossible. At a family dinner, my father even prayed that my husband and I would have “ordinary lives.” In retrospect, I think the prayer was directed to me, as if he had been saying, “Don’t aim for greatness. Be content with success in a respectable middle-class profession.”

Unlike Chua, I rebelled. Early on, my parents wanted me to become a doctor, lawyer or engineer, and I had enrolled at UC Irvine as a biology major. But after a year and a half, and without consulting my parents, I got off the pre-med track and hopped a freight train heading nowhere: I chose to study not what was prestigious or respectable but what I loved (literature and philosophy). My parents stopped paying for my education, and I had to work as a temp and teaching assistant to put myself through the rest of college and graduate school. When I finally got my Ph.D., I asked my mother, “Are you proud of me now?” Her response was, “We never asked for that.” This has not been good for our relationship.

●

Precisely because I was raised in a Tiger Mom world, but rebelled against it, I understand where Chua is coming from, but I can also see what remains invisible to her. Being a Tiger Mom is not just a matter of using harsh parenting techniques to ensure that children live up to their potential. It involves seeing one’s whole world—one’s work, prospects for happiness, family ties, sense of obligations, sense of self, etc.—from the perspective of an immigrant drawn to America’s meritocratic mythology. And this makes conflicts between Tiger Moms and their children almost inevitable.

The situation of a person born into poverty in a war-torn country obviously differs from that of a person born and raised in conditions of (relative) prosperity. For the Asian immigrant who has left everything behind and has nothing to fall back on except his or her own efforts, “succeeding” is an all-consuming compulsion. Straight A’s, gold medals, promotions and Nobel Prizes are not simply the rewards of one’s hard work but evidence of one’s worth. They are not goals which, having been reached, can be enjoyed in and of themselves. Specific achievements are never enough; they do not slake but rather fuel the desire for success.

It is this urgent quality of drivenness that the children of Asian immigrants may not feel in their bones. Simple desire for success they can understand; what is alien to them is their parents’ desperate compulsion toward it. The child raised with a community of intimates who value her for herself will find it bizarre to stake her sense of personal esteem on public affirmations of success. What matters to my father is not that he works in software development, but that he is in a senior position. My siblings and I, on the other hand, are more defined by the kind of jobs we chose (physician, computer programmer and humanities professor). Success matters, but the specific job matters more.

Tiger Parents often live in isolation from the culture of their adopted country, and foolishly expect their children to do the same. But children pick up ideas the same way they pick up germs: inevitably and incessantly. Floating around them are messages like: “Be yourself”; “Do what you love”; “Have fun”; “Follow your bliss”; “Believe in yourself.” And when well-meaning people ask Tiger Mothered young adults whether, for all their success, they are truly happy, the question can be profoundly disquieting; for the first time, their most basic assumptions are thrown into doubt.

Asian families are notorious for their bitter feuds and decade-long estrangements. The high drama, the suicides, estrangements and disownments show that what is at stake is the whole way of being of the family, that is, everything that gives the family its identity and raison d’être. In a Moscow restaurant—what better setting?—Chua’s daughter smashed a glass on the floor and rebelled, not just against her mother’s discipline but in protest against her family’s whole ethos: “I hate the violin. I hate my life! I hate you, and I hate this family!”

I have an aunt who has not spoken to her mother (my grandmother) for more than forty years, as long as I have been alive. They will go to their graves before they make their peace. I know a Korean American young man who, after years of kowtowing and deception, finally blew up at his parents and told them what he really thought and how he really lived; they responded by disowning him and telling friends and neighbors he was dead.

As absurd as it may appear from the outside, the histrionics make sense as a response to a Manichean logic that sees the world as an arena of non-stop competition that sorts humanity into winners and losers. Since children’s success or failure brings honor or shame directly on their parents, parents have every reason to mold their children by any means necessary. But headstrong mothers breed headstrong daughters, and it is understood that one fights fire with fire. So Tiger Parenting can generate conflict far beyond anything Chua describes: public meltdowns; destruction of property; displays of self-mutilation; and violence involving knives, kitchen utensils, gardening tools and household appliances. Such tactics are not only perfectly appropriate, but proofs of one’s mettle. Whoever has the most impressive and forceful display of emotion prevails.

When the “Asian” style of parenting fails, it does so in the saddest and most self-destructive ways. My cousin slashed her wrists in the bathtub where her mother found her lying in a warm mix of water and blood (she survived). At Cornell, thirteen of 21 suicides between 1996 and 2006 were Asians or Asian Americans (who constituted only 14 percent of the student body at the time). In this country, Asian American women have the highest rates of suicide. It is irresponsible self-deception to maintain that the children of Tiger Moms suffer no ill effects from the way they are raised.

●

I have lived and left behind the Tiger Mom way of life, and I am convinced that Western ways are better. In contrast to Tiger Mom parenting, Western parenting rightly recognizes that childhood is a time to be treasured for its own sake, that we should “let kids be kids.” Accordingly, Western culture is filled with works of art that exalt and celebrate the intrinsic worth and dignity of childhood—from William Wordsworth to A. A. Milne. In Winnie the Pooh, Christopher Robin says, “What I like most of all is just doing nothing.” The tragedy at the end of the book is that Christopher Robin has to go to school: “No one else in the forest knew why or where he was going, just that it had something to do with twice-times, and how to make things called ABCs, and where a place called Brazil is.”

But I also think Western ways of parenting are in trouble. The ideas that commonly guide parents today are actually debased and derivative versions of an ethos that has been reduced to clichés (e.g., “Be yourself”; “Do what you love”; “Live your own life”). Rather than simply attacking Chua and reaffirming Western ways of parenting, the task before us is to recover and articulate our own ethos.

At its best, the Western style of parenting aims to help children live authentically, that is, to take on the responsibility to decide for themselves what to do and how to live. My understanding of the world is inauthentic to the extent that I have simply inherited it from my parents or absorbed it from the people around me, without having made any responsible effort to measure it against my own experience. My discourse is inauthentic if I accept and repeat what others say without trying to understand through my own effort what it means or whether it is true. Inauthentic understanding and discourse are dominated and governed by the dictatorship of “the everyone” or “the they,” as the German philosopher Martin Heidegger writes:

In contrast, what is authentic is what is our own—what we have that we have made our own. My understanding and discourse is more authentic the more it comes out of my own experience, thought and judgments. My life is more authentic the less it is dominated by “the everyone” and the more it is governed by my own understanding, concerns, desires, tastes, goals, etc. One of the clearest articulations of this idea of authenticity comes in Leo Tolstoy’s novella, The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Tolstoy tells the life of a man who becomes successful and respectable by ignoring his own moral intuitions and living according to the bourgeois values of “the everyone”:

Tolstoy doesn’t tell us what exactly Ivan Ilyich did; he doesn’t denounce this or that immoral act. The point is that Ivan let his own sense of good and bad be overruled by the dictates of common opinion. The tragedy of his life is not that he failed to achieve something, but that the ideals he did succeed in reaching were not truly his own. The novella has often been read as a condemnation of the bourgeois ethos whose highest values are success and respectability. It has also been read as an indictment of conformism. While both these readings are plausible, at the deepest level the novel is about inauthenticity. What is wrong with Ivan Ilyich’s life is not just that it was guided by a narrow and superficial set of values, but that Ivan simply accepted those values without questioning them.

The ethos of authenticity undergirding Western parenting can be seen in Western attitudes toward art, education and work. Unlike in the Tiger Mother ethos, art and education are seen as ends in themselves, rather than means. Both are considered essential for cultivating an authentic engagement with the world—which involves casting aside the opinions of the “everyone” in favor of developing one’s own. This ideal of authenticity even guides Western attitudes toward work, especially the notion that children should be free to choose their own career, which reflects the old Western idea that work should be experienced as something we are personally called upon to do. No one else can decide what my calling is; only I can find the work that is properly my own.

Grafted onto these attitudes is the sense that in life it is possible to aim at something higher than success. Success is good, but more important than success is greatness. In this ethos there is a peculiar place of honor for people who were great without being successful. Vincent van Gogh failed as an art dealer and as a Christian missionary before finally cutting off his ear, being put in an insane asylum and killing himself at the age of 37. He was not a success, but success seems petty next to his greatness as an artist. This aspiration to greatness is absent from every instrumental attitude to art, education and work. Nothing great has ever been achieved by people who see such things solely as instruments for achieving success and respectability.

●

Chua is perhaps at her most “Chinese” when, in response to her husband’s argument that children don’t owe their parents anything, she remarks, “This strikes me as a terrible deal for the Western parent” (my italics). On a gut level, she can’t think of the relation between parents and children in terms other than debt and obligation, so her husband’s objections simply make no sense. My mother once said, as if she were speaking of life on Mars, “Here [in America] the parents are the slaves of their children.” What she saw of American parenting violated her deepest sense of the natural order of things. Despite having lived in America for nearly forty years, the country remains for her a baffling world in which all that is good and right and proper is turned on its head.

The nature of the differences between Asian Americans and their immigrant parents entails that conflict cannot be resolved through the channels taken for granted by Western families, such as negotiation and reasoned dialogue (like I said before, colorful and sustained displays of emotion and violence are the more effective and accepted means of getting through to the other). Once, when I had a particularly bad argument with my mother—we hadn’t talked for months—a concerned relative of my husband’s asked, “Why can’t you just sit down at the table and talk things through?” What he couldn’t fathom was that that would have been impossible. To sit down at the table with me would have been, for my mother, an admission of defeat. Ahab and Moby Dick do not sit down at the table and talk things through!

Westerners tend to think of disputes in terms of the metaphor of perspective: each person has a standpoint which gives them a distinct perspective, and each perspective offers a clear but limited view of the world; no one perspective is comprehensive, so disputes can be resolved by exchanging opinions and finding the grains of truth in many different points of view. Tiger Parents, on the other hand, tend to think of disputes in the metaphor of a path: there is one true path that their children ought to follow, and any deviation from that path is a sign of error or delinquency. Americanized children cannot accept the basic terms in which their parents think, since those terms deny that different opinions have any legitimacy. The parents in turn cannot accept the terms in which their children think, since that would be a deviation from what they regard as the rightful path. To regard other ideas as “different perspectives” would be to admit their own way of thought might be in error.

These differences are made all the more irresolvable by the fact that Tiger Parents perceive the conflict between parents and children as a battle of wills in which there can be only winners and losers (to compromise is to lose). Hence the title of Chua’s book, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. When Chua “retreated” in the face of her daughter’s meltdown, she suffered a tactical defeat. But the basic terms in which she thinks of parenting didn’t change. She may have lost one skirmish but she still thinks of parenting as a war of attrition. In the case of one daughter, hostilities apparently commenced when the girl was only three: “I was determined to raise an obedient Chinese child … if it killed me.” When her daughter dared to defy her—by refusing to play the piano or come in out of the cold—Chua realizes, “I had underestimated Lulu, not understood what she was made of. She would sooner freeze to death than give in.” However, Chua quickly rallies: “But Lulu had underestimated me too. I was just re-arming. The battle lines were drawn, and she didn’t even know it.”

Asian American fiction is filled with fantasies of conflict resolution. After a series of misunderstandings and personal crises, the mother and daughter have a meeting of hearts which allows them to better understand and appreciate one another. It turns out that the mother (or grandmother) was right after all; but at the same time, the mother learns to give autonomy and respect to the daughter. This typical narrative is pure wish fulfillment; the underlying fantasy is that differences are all a matter of misunderstanding. Stories like these appeal to Asian Americans because they articulate exactly what we want, which is to believe that real reconciliation is possible. But the fantasy, understandable as it is, obscures the depth of the differences at issue and fails to appreciate what it is that makes real-life reconciliation so difficult.

Some children do live more or less according to their parents’ ethos. I know a Chinese American student who came from a family of doctors and was happy to follow in their footsteps and enroll at Harvard Medical School. But many Asian Americans can imitate their parents only by suppressing their real values. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer believed that most human beings are doomed to be unhappy but that nature nevertheless produces a few people who are genuinely happy, who serve as “decoys” and who make people even more miserable by creating the illusion that happiness is possible. The children who genuinely adopt their parents’ ethos, like this Chinese American legacy doctor, are the Schopenhauerian “decoys” of the Asian American community.

The easiest alternative is to pretend. Keeping up appearances while sneaking around behind our parents’ backs is a long and cherished tradition within the Asian American community. The most resourceful children, typically daughters, know there are many shades of acceptable pretense. It is simple enough, for example, to put on a show of obeisance in the presence of one’s parents and then turn around and do whatever the hell one pleases as soon as they are out of sight. Some families have a kind of “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. Or one can simply lie. What may appear as “Asian” hypocrisy and sneakiness from the outside is often the only solution to a desperate situation: parents are appeased; children get some breathing room; harmony reigns; everyone wins. All it takes is a little creativity. I have a Korean American friend whose boyfriend moved in with her for two years without her parents’ knowledge or consent. This meant that for two years her boyfriend could never answer the phone, for fear that it might be her parents calling. Whenever her parents visited, they had to evacuate his possessions and erase all trace of his presence from their apartment. She explained, “It’s better that way. They didn’t need to know. They didn’t want to know. Why stir up conflict? Later we got engaged and then married. So it all worked out.”

But pretending has its limits. Usually it works for a while and then one has to start making decisions that can’t be hidden. Dan Choi, the gay Korean American lieutenant who challenged the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, has said that the hardest thing about his experience was coming out to his family (his father is a Baptist minister). After enduring relentless pressure from his mother to marry a Korean girl, he had no choice but to come out; he told her, “I am not going to marry a Korean girl, nor am I going to marry a White girl. I am gay.”

Sometimes you have to rebel, even if it means cutting yourself off from your parents. Obviously this isn’t ideal—you end up with no family. I know from experience: I finally stood up to my mother two years ago and I haven’t seen or spoken to any member of my family since. (Although I have exchanged e-mails with my father and siblings, and my mother and I are now “friends” on Facebook.)

●

A real reconciliation would have to begin with a reframing of the conflict. The conflict between Tiger Parents and their children may not be a battle between right and wrong but a collision between right and right. What is ultimately at stake is the differences between two êthea—two visions of what it is right to do and good to be. The ancient Greeks had a name for this kind of collision between right and right: tragedy. Tragedies are stories that dramatize conflicts between two sets of values, each of which is worthy of respect. The Greeks saw that such conflicts tend to end unhappily when both sides refuse to listen to or respect the other. But not all tragedies end unhappily; some end with reconciliation.